Low Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound for Bone Tissue Engineering

Abstract

:1. Introduction

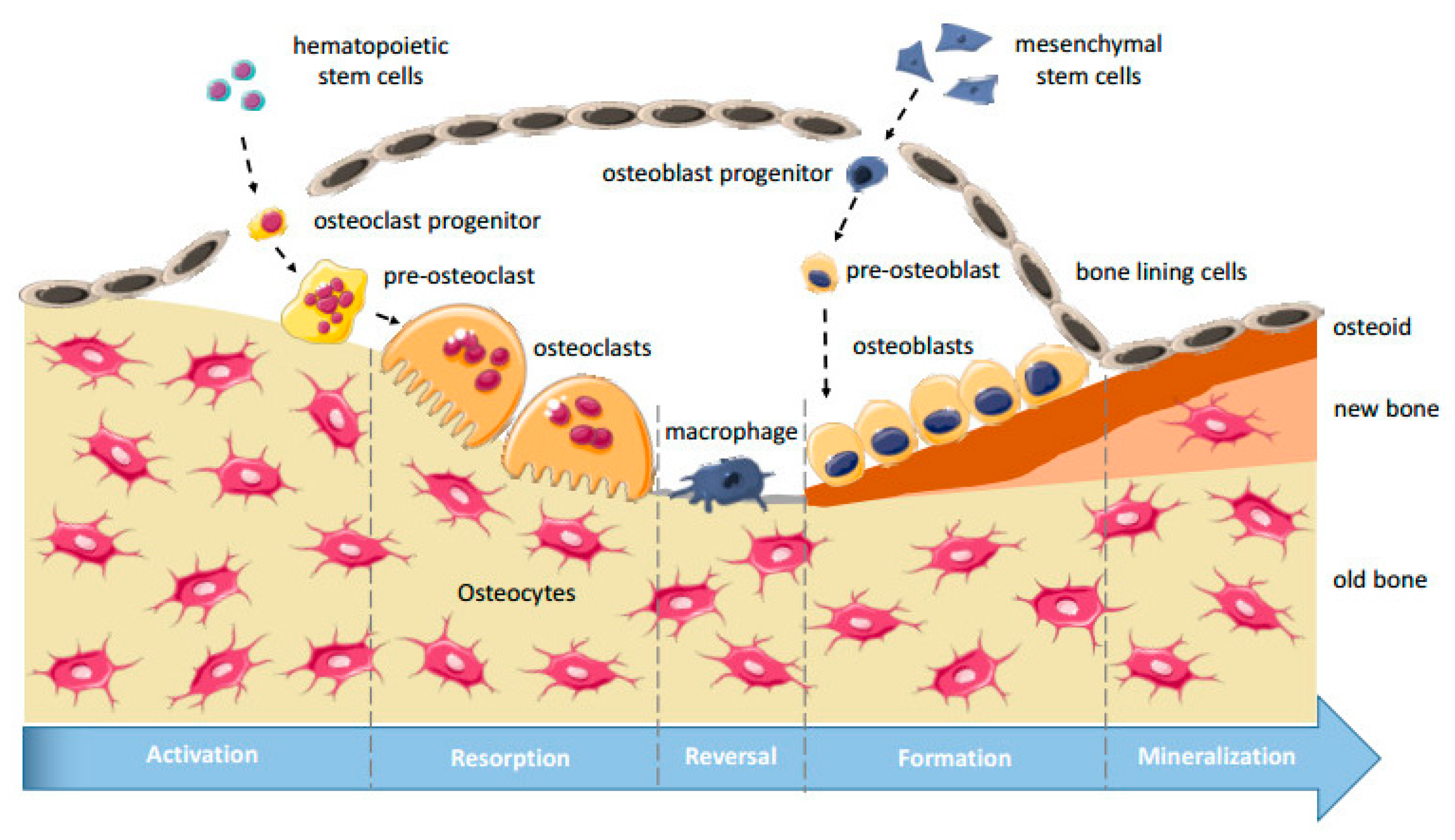

2. Mechanisms of Bone Healing and Mechanical Stimulation

2.1. Bone Structure, Bone Remodeling, and Osteogenesis

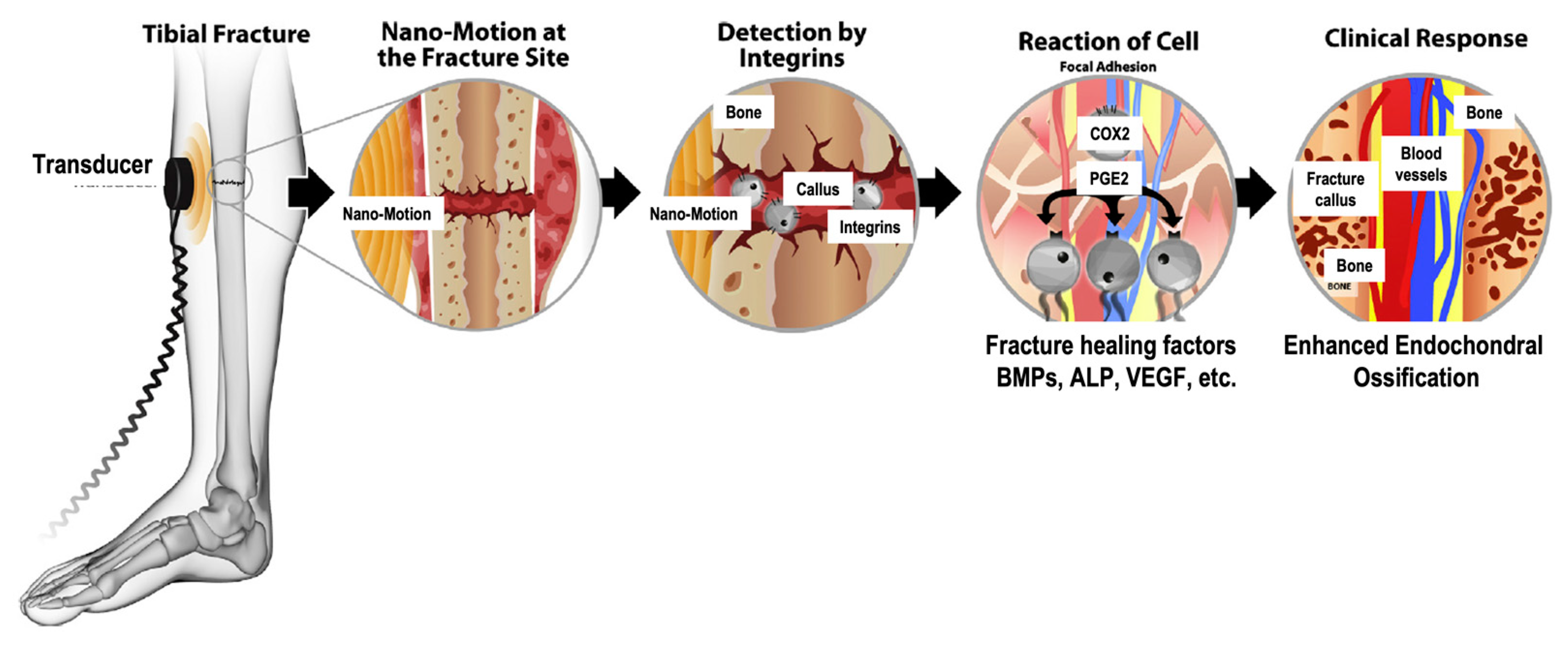

2.2. Mechanotransduction and Biological Mechanisms of LIPUS

2.3. The Mechanostat Hypothesis

2.4. Mechanotherapy

3. Low Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound (LIPUS)

4. LIPUS Devices

5. Applications of LIPUS for Bone Tissue Engineering

| Study | Cell and Scaffold Type | Ultrasound Parameters | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Veronick et al. (2016) [18] | Cell Type: MC3T3 mouse osteoblast cells Scaffold Material: type 1 collagen hydrogels | Frequency: 1 MHz wave with 1 kHz repetition frequency Pulse mode: 20, 50, or 100% duty cycle Intensity: 30 mW/cm2 | LIPUS produced a measurable force and hydrogel deformation. LIPUS increased alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin gene expression. The effect on gene expression was indirectly proportional to hydrogel stiffness and directly proportional to duty cycle. |

| Zhou et al. (2016) [20] | Cell Type: human mesenchymal cells (hMSCs) Scaffold Material: polyethylene glycol diacrylate bio inks containing RGDS or nHA | Intensity: 150 mW/cm2 Frequency: 1.5 MHz Duty cycle: 20% | LIPUS increased MSC proliferation, alkaline phosphatase activity, mineralization, and total protein content in a 3D printed RGDS nHA scaffold. |

| Feng et al. (2019) [21] | Cell type: MC3T3-E1 mouse pre-osteoblast cells Scaffold Material: Ti6Al4V | Intensity: 40 mW/cm2 Pulse Length: 1 ms Frequency: 1 MHz and 3.2 MHz Exposure: 20 min daily for either 3 weeks or 6 weeks. | LIPUS had no significant impact on cell proliferation, increased alkaline phosphatase activity and osteocalcin expression, and increased volume and amount of new bone formation No significant difference was found between 1 MHz and 3.2 MHz frequencies. The 1 MHz frequency was slightly better for ALP activity, OCN content, scaffold pore occupancy, bone area percentage, and calcium deposition, but the difference was not statistically significant. |

| Kuang et al. (2019) [22] | Cell Type: dental follicle cells (DFCs) Scaffold Material: OsteoBoneTM ceramic | Intensity: 90 mW/cm2 Frequency: 1.5 MHz Pulse Repetition: 1 kHz Pulse Duration: 200 μs Exposure: 20 min daily for 3, 5, 7, 9, or 21 days | In vitro, LIPUS increased ALP, Runx2, OSX, and COL-I gene expression and the formation of mineralized nodules. In vivo, LIPUS treatment improved fibrous tissue and blood vessel growth. |

| Wu et al. (2015) [23] | Cell Type: MC3T3-E1 mouse pre-osteoblast cells Scaffold Material: silicon carbide (SiC) | Intensity: 30 mW/cm2 Frequency: 1 MHz Pulse length: 1 ms Pulse repetition: 100 Hz Exposure: 20 min for 4 or 7 days | LIPUS improved cell density, cell ingrowth, dsDNA content, and alkaline phosphatase activity |

| Carina et al. (2017) [37] | Cell Type: human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) Scaffold Material: magnesium dopped hydroxyapatite and type 1 collagen composite (MgHA/Coll) | Intensity: 20 mW/cm2 Frequency: 1.5 MHz Pulse repetition: 1 kHz Burst length: 200 μs Exposure: 20 min per day for 5 d/wk for 1 or 2 weeks | LIPUS improved hMSC viability and upregulated several osteogenic genes (ALPL, BGLAP, MAPK1, MAPK6, and VEGF). |

| Zhu et al. (2020) [44] | Cell Type: MC3T3-E1 mouse pre-osteoblast cells (for in vitro Alizarin red staining experiments) Scaffold Material: poly-L-lactic acid/polylactic-co-glycolic acid/poly-ε-caprolactone (PLLA/PLGA/PCL) | Intensity: 30 mW/cm2 Exposure: 20 min daily for 12 weeks | LIPUS improved load carrying capacity, accelerated bone formation, angiogenesis, and differentiation. LIPUS was used to alleviate the effects of osteonecrosis. |

| Iwai et al. (2007) [72] | Cell Type: MC3T3-E1 mouse pre-osteoblast cells Scaffold Material: hydroxyapatite | Intensity: 30 mW/cm2 Frequency: 1.5 MHz Burst width: 200 μs Wave Repetition: 1 kHz Exposure: not specified | LIPUS did not affect biomechanics/compressive strength of hydroxyapatite ceramic LIPUS improved osteoblast number and bone area in the center of implanted, porous scaffold. LIPUS improved volume of mineralized tissue and MC3T3-E1 migration. |

| Wang, J et al. (2014) [73] | Cell Type: bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) Scaffold Material: β-tricalcium phosphate composite | Frequency: 1.5 MHz Burst width: 200 μs Wave Repetition: 1 kHz Intensity: 30 mW/cm2 Exposure: 20 min daily for 5, 10, 25, or 50 days | LIPUS increased ALP activity and OCN content. Additionally, LIPUS improved the degree of soft tissue repair, increased blood flow, and resulted in more extensive bone repair. LIPUS did not impact the compressive strength of the β-TCP scaffold. |

| Hui et al. (2011) [74] | Cell Type: mesenchymal stem cell derived osteogenic cells Scaffold Material: tricalcium phosphate | Frequency: 1.5 MHz Burst width: 200 μs Wave Repetition: 1 kHz Intensity: 30 mW/cm2 Exposure: 20 min daily; 5 d/wk, 7 weeks | LIPUS increased spinal fusion at L5 and L6 in New Zealand white rabbits. |

| Cao et al. (2017) [75] | Cell Type: MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblast cells Scaffold Material: Ti6Al4V | Frequency: 1 MHz Pulse length: 1 ms Pulse repetition: 100 Hz Intensity: 30 mW/cm2 Exposure: 20 min daily for: 1, 4, or 7 days (in vitro) 3 or 6 weeks (in vivo) | An intensity of 30 mW/cm2 was found to be most effective at promoting osteogenic differentiation In vitro: LIPUS had no effect on cell proliferation but increased ALP activity, OCN content, and cell ingrowth into the scaffold. In vivo: LIPUS increased/improved amount and volume of new bone formed and the bone maturity. |

| Liu et al. (2020) [76] | Cell Type: bone marrow stromal cells Scaffold Material: Ti6Al4V coated with BaTiO3 | Frequency: 1.5 MHz sine wave repeating at 1 kHz Pulse duration: 200 μs Intensity: 30 mW/cm2 Exposure: 10 min daily for 7 or 14 days | When combined with BaTiO3 LIPUS increased ALP activity and expression of Runx-2, Col-1, and OPN on a titanium scaffold. LIPUS improved the amount of new bone formed (greater volume and filled the scaffold pores to a greater degree). |

| Fan et al. (2020) [77] | Cell Type: bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells Scaffold Material: Ti6Al4V with BaTiO3 coating | Intensity: 30 mW/cm2 Frequency: 1.5 MHz Pulse Repetition: 1 kHz Pulse duration: 200 μs Exposure: 10 min daily for 4, 7, or 14 days | In vitro: LIPUS improved cell adhesion, proliferation, and gene expression on a titanium scaffold especially when paired with BaTiO3 coating to induce the piezoelectric effect. In vivo: LIPUS improved new bone formation, osteointegration, mineral apposition rate (MAR), and bonding strength of bone and scaffold. |

| Veronick et al. (2018) [78] | Cell Type: MC3T3-E1 mouse pre-osteoblast cells Scaffold Material: type 1 collagen hydrogels | Frequency: 1 MHz wave with 1 kHz repetition frequency Pulse mode: 20, 50, or 100% duty cycle Intensity: 30 mW/cm2 | Hydrogel deformation was a function of hydrogel stiffness and duty cycle. LIPUS upregulated COX-2 and PGE2 expression. Effects of LIPUS and hydrogel encapsulation were additive. |

| Wang, Y et al. (2014) [79] | Cell Type: human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) Scaffold Material: RGD grafted oxidized sodium alginate/N-succinyl chitosan hydrogel (RGD-OSA/NSC) | Duty Cycle: 20% Frequency: 1 MHz Intensity: 200 mW/cm2 Exposure: 10 min daily for 1, 3, 7,10, 14, 0r 21 days | LIPUS improved cell proliferation, ALP activity, and mineralization. |

| Hsu et al. (2011) [80] | Cell Type: MG63 osteoblast-like cells Scaffold Material: commercial purity titanium (CP-Ti) | Intensity: 0, 50, 150, and 300 mW/cm2 Frequency: 1 MHz Pulse Repetition: 100 Hz Exposure: 3 min daily for 5 days (in vitro); 10 min daily for 20 or 30 days (in vivo) | LIPUS improved cell viability and ALP activity in vitro. LIPUS improved blood flow and the maturation of collagen fibers. Pulsed ultrasound was better than continuous ultrasound for |

| Nagasaki et al. (2015) [81] | Cell Type: adipose derived stem cells (ADSCs) Scaffold Material: nanohydroxyapatite (nHA) | Intensity: 60 mW/cm2 Frequency: 3.0 MHz sine waves repeated at 100 Hz Exposure: 10 min daily for 7, 14, or 21 days | LIPUS increased calcium and phosphate deposition and bone thickness for adipose derived stem cells in a nHA scaffold. |

5.1. Cell Morphology and Attachment

5.2. Cell Viability and Proliferation

5.3. Osteogenic Differentiation

5.3.1. Early Osteogenic Markers—Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity

5.3.2. Late Osteogenic Markers—Osteocalcin (OCN)

5.3.3. Other Osteogenic Markers

5.4. Bone Mineralization

5.5. Bone Area and Volume

5.6. Vascularization and Angiogenesis

5.7. Osseointegration

5.8. Scaffold Biomechanics

6. Synergistic Effects of LIPUS with Other Bone Tissue Engineering Techniques

6.1. D Encapsulation

6.2. Piezoelectric Effect

6.3. BMP-2 Delivery

6.4. Scaffold Modification with Peptides or Minerals

7. Optimal LIPUS Parameters for Bone Tissue Engineering

8. Limitations and Future Directions of LIPUS

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Victoria, G.; Petrisor, B.; Drew, B.; Dick, D. Bone stimulation for fracture healing: What′s all the fuss? Indian J. Orthop. 2009, 43, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, S.; He, H.; Li, B.; Hou, T. Hydrogel as a Biomaterial for Bone Tissue Engineering: A Review. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F.-H.; Shen, P.-C.; Jou, I.-M.; Li, C.-Y.; Hsieh, J.-L. A Population-Based 16-Year Study on the Risk Factors of Surgical Site Infection in Patients after Bone Grafting: A Cross-Sectional Study in Taiwan. Medicine 2015, 95, e5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polo-Corrales, L.; Latorre-Esteves, M.; Ramirez-Vick, J.E. Scaffold Design for Bone Regeneration. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014, 14, 15–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, X.; Stroll, S.I.; Lantigua, D.; Suvarnapathaki, S.; Camci-Unal, G. Eggshell particle-reinforced hydrogels for bone tissue engineering: An orthogonal approach. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 2675–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Walsh, K.; Hoff, B.L.; Camci-Unal, G. Mineralization of Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, S.M. Cortical or Trabecular Bone: What’s the Difference? Am. J. Nephrol. 2018, 47, 373–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, S.C.; Odgren, P.R. Chapter 1—Structure and Development of the Skeleton. In Principles of Bone Biology, 2nd ed.; Bilezikian, J.P., Raisz, L.G., Rodan, G.A., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mackie, E.J.; Ahmed, Y.A.; Tatarczuch, L.; Chen, K.S.; Mirams, M. Endochondral ossification: How cartilage is converted into bone in the developing skeleton. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, P.; Koller, A.; Sharma, S. Physiology, Bone Remodeling. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Duan, N.; Zhu, G.; Schwarz, E.M.; Xie, C. Osteoblast–osteoclast interactions. Connect. Tissue Res. 2018, 59, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rucci, N. Molecular biology of bone remodelling. Clin. Cases Miner. Bone Metab. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Osteoporos. Miner. Metab. Skelet. Dis. 2008, 5, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, J.A.; Partridge, N.C. Physiological Bone Remodeling: Systemic Regulation and Growth Factor Involvement. Physiology 2016, 31, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proff, P.; Römer, P. The molecular mechanism behind bone remodelling: A review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2009, 13, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saftig, P.; Hunziker, E.; Everts, V.; Jones, S.; Boyde, A.; Wehmeyer, O.; Suter, A.; von Figura, K. Functions of cathepsin K in bone resorption. Lessons from cathepsin K deficient mice. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2000, 477, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwayama, T.; Okada, T.; Ueda, T.; Tomita, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Takedachi, M.; Wakisaka, S.; Noda, T.; Ogura, T.; Okano, T.; et al. Osteoblastic lysosome plays a central role in mineralization. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Truesdell, S.L.; Saunders, M.M. Bone remodeling platforms: Understanding the need for multicellular lab-on-a-chip systems and predictive agent-based models. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2020, 17, 1233–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronick, J.; Assanah, F.; Nair, L.S.; Vyas, V.; Huey, B.; Khan, Y. The effect of acoustic radiation force on osteoblasts in cell/hydrogel constructs for bone repair. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barque de Gusmão, C.V.; Alves, J.M.; Belangero, W.D. Acoustic Therapy as Mechanical Stimulation of Osteogenesis. In Advanced Techniques in Bone Regeneration; Rozim Zorzi, A., Batista de Miranda, J., Eds.; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Castro, N.; Zhu, W.; Cui, H.; Aliabouzar, M.; Sarkar, K.; Zhang, L.G. Improved Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell Osteogenesis in 3D Bioprinted Tissue Scaffolds with Low Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Stimulation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Feng, L.; Liu, X.; Cao, H.; Qin, L.; Hou, W.; Wu, L. A Comparison of 1- and 3.2-MHz Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound on Osteogenesis on Porous Titanium Alloy Scaffolds: An In Vitro and In Vivo Study. J. Ultrasound Med. 2019, 38, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kuang, Y.; Hu, B.; Xia, Y.; Jiang, D.; Huang, H.; Song, J. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound promotes tissue regeneration in rat dental follicle cells in a porous ceramic scaffold. Braz. Oral Res. 2019, 33, e0045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Lin, L.; Qin, Y.-X. Enhancement of Cell Ingrowth, Proliferation, and Early Differentiation in a Three-Dimensional Silicon Carbide Scaffold Using Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound. Tissue Eng. Part A 2015, 21, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Azuma, Y.; Ito, M.; Harada, Y.; Takagi, H.; Ohta, T.; Jingushi, S. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Accelerates Rat Femoral Fracture Healing by Acting on the Various Cellular Reactions in the Fracture Callus. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2001, 16, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pounder, N.M.; Harrison, A.J. Low intensity pulsed ultrasound for fracture healing: A review of the clinical evidence and the associated biological mechanism of action. Ultrasonics 2008, 48, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S.; Darwood, A.; Masouros, S.; Higgins, C.; Ramasamy, A. Mechanotransduction in osteogenesis. Bone Jt. Res. 2020, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T.; Fujita, N.; Tsuji-Tamura, K.; Kitagawa, Y.; Fujisawa, T.; Tamura, M.; Sato, M. Osteocytes as main responders to low-intensity pulsed ultrasound treatment during fracture healing. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Kato, Y.; Zhao, S.; Luo, J.; Sprague, E.; Bonewald, L.F.; Jiang, J.X. PGE2 Is Essential for Gap Junction-Mediated Intercellular Communication between Osteocyte-Like MLO-Y4 Cells in Response to Mechanical Strain. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 3464–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Bakker, A.D.; Klein-Nulend, J. The role of osteocytes in bone mechanotransduction. Osteoporos. Int. 2009, 20, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Chen, M.; Zhu, Z. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound regulates proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts through osteocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 418, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, V.; Yadav, S.; McCormick, S. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Modulates Shear Stress Induced PGHS-2 Expression and PGE2 Synthesis in MLO-Y4 Osteocyte-Like Cells. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 39, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, F.; Puts, R.; Vico, L.; Raum, K. Stimulation of bone repair with ultrasound: A review of the possible mechanic effects. Ultrasonics 2014, 54, 1125–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Schmelz, A.; Seufferlein, T.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Bachem, M.G. Molecular Mechanisms of Low Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound in Human Skin Fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 54463–54469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, C.-H.; Yang, R.-S.; Huang, T.-H.; Lu, D.-Y.; Chuang, W.-J.; Huang, T.-F.; Fu, W.-M. Ultrasound Stimulates Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression and Increases Bone Formation through Integrin, Focal Adhesion Kinase, Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase, and Akt Pathway in Osteoblasts. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 69, 2047–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takeuchi, R.; Ryo, A.; Komitsu, N.; Mikuni-Takagaki, Y.; Fukui, A.; Takagi, Y.; Shiraishi, T.; Morishita, S.; Yamazaki, Y.; Kumagai, K.; et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound activates the phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase/Akt pathway and stimulates the growth of chondrocytes in three-dimensional cultures: A basic science study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2008, 10, R77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whitney, N.P.; Lamb, A.C.; Louw, T.M.; Subramanian, A. Integrin-Mediated Mechanotransduction Pathway of Low-Intensity Continuous Ultrasound in Human Chondrocytes. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2012, 38, 1734–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carina, V.; Costa, V.; Raimondi, L.; Pagani, S.; Sartori, M.; Figallo, E.; Setti, S.; Alessandro, R.; Fini, M.; Giavaresi, G. Effect of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on osteogenic human mesenchymal stem cells commitment in a new bone scaffold. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2017, 15, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, A.; Lin, S.; Pounder, N.; Mikuni-Takagaki, Y. Mode & mechanism of low intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) in fracture repair. Ultrasonics 2016, 70, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Naruse, K.; Mikuni-Takagaki, Y.; Azuma, Y.; Ito, M.; Oota, T.; Kameyama, K.-Z.; Itoman, M. Anabolic Response of Mouse Bone-Marrow-Derived Stromal Cell Clone ST2 Cells to Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 268, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.M.; Manigrasso, M.B.; O’Connor, J.P. Cyclo-Oxygenase 2 Function Is Essential for Bone Fracture Healing. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2002, 17, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.S.; Yoo, J.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Paik, S.; Han, C.D.; Lee, J.W. The Effects of COX-2 Inhibitor During Osteogenic Differentiation of Bone Marrow-Derived Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2010, 19, 1523–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossman, J.; Alzaheri, N.; Abdallah, M.-N.; Tamimi, F.; Flood, P.; Alhadainy, H.; El-Bialy, T. Low intensity pulsed ultrasound increases mandibular height and Col-II and VEGF expression in arthritic mice. Arch. Oral Biol. 2019, 104, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.-Y.; Wu, S.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-C.; Wang, F.; Yang, Y.-L.; Li, M.; Wei, X.-Z. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound promotes endothelial cell-mediated osteogenesis in a conditioned medium coculture system with osteoblasts. Medicine 2017, 96, e8397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Cai, X.; Lin, T.; Shi, Z.; Yan, S. Low-intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Enhances Bone Repair in a Rabbit Model of Steroid-associated Osteonecrosis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2015, 473, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korstjens, C.M.; Rutten, S.; Nolte, P.A.; Van Duin, M.A.; Klein-Nulend, J. low-intensity pulsed ultrasound increases blood vessel size during fracture healing in patients with a delayed-union of the osteotomized fibula. Histol. Histopathol. 2018, 33, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, K.; Angle, S.R.; Kanaji, A.; Aher, C.; Karwo, D.G.; Sumner, D.R.; Virdi, A.S. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) and cell-to-cell communication in bone marrow stromal cells. Ultrasonics 2011, 51, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, A.; Paton, S.; Zannettino, A.C.; Gronthos, S. Conditional knockout of ephrinB1 in osteogenic progenitors delays the process of endochondral ossification during fracture repair. Bone 2020, 132, 115189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Paul, E.M.; Sathyendra, V.; Davison, A.; Sharkey, N.; Bronson, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Gross, T.S.; Donahue, H.J. Enhanced Osteoclastic Resorption and Responsiveness to Mechanical Load in Gap Junction Deficient Bone. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McBride-Gagyi, S.H.; McKenzie, J.A.; Buettmann, E.G.; Gardner, M.J.; Silva, M.J. Bmp2 conditional knockout in osteoblasts and endothelial cells does not impair bone formation after injury or mechanical loading in adult mice. Bone 2015, 81, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phillips, J.A.; Almeida, E.A.; Hill, E.L.; Aguirre, J.I.; Rivera, M.F.; Nachbandi, I.; Wronski, T.J.; van der Meulen, M.C.H.; Globus, R.K. Role for β1 integrins in cortical osteocytes during acute musculoskeletal disuse. Matrix Biol. 2008, 27, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekaran, A.; Shoemaker, J.T.; Kavanaugh, T.E.; Lin, A.S.; LaPlaca, M.C.; Fan, Y.; Guldberg, R.E.; García, A.J. The effect of conditional inactivation of beta 1 integrins using twist 2 Cre, Osterix Cre and osteocalcin Cre lines on skeletal phenotype. Bone 2014, 68, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delgado-Calle, J.; Tu, X.; Pacheco-Costa, R.; McAndrews, K.; Edwards, R.; Pellegrini, G.G.; Kuhlenschmidt, K.; Olivos, N.; Robling, A.; Peacock, M.; et al. Control of Bone Anabolism in Response to Mechanical Loading and PTH by Distinct Mechanisms Downstream of the PTH Receptor. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017, 32, 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iura, A.; McNerny, E.G.; Zhang, Y.; Kamiya, N.; Tantillo, M.; Lynch, M.; Kohn, D.H.; Mishina, Y. Mechanical Loading Synergistically Increases Trabecular Bone Volume and Improves Mechanical Properties in the Mouse when BMP Signaling Is Specifically Ablated in Osteoblasts. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimston, S.K.; Brodt, M.D.; Silva, M.J.; Civitelli, R. Attenuated Response to In Vivo Mechanical Loading in Mice With Conditional Osteoblast Ablation of the Connexin43 Gene (Gja1). J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008, 23, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lawson, L.Y.; Brodt, M.D.; Migotsky, N.; Chermside-Scabbo, C.J.; Palaniappan, R.; Silva, M.J. Osteoblast-Specific Wnt Secretion Is Required for Skeletal Homeostasis and Loading-Induced Bone Formation in Adult Mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.; Wergedal, J.E.; Das, S.; Kesavan, C. Conditional disruption of miR17-92 cluster in collagen type I-producing osteoblasts results in reduced periosteal bone formation and bone anabolic response to exercise. Physiol. Genom. 2015, 47, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, K.-H.W.; Baylink, D.J.; Sheng, M.H.-C. Osteocyte-Derived Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Is Not Essential for the Bone Repletion Response in Mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0115897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.H.W.; Baylink, D.J.; Zhou, X.-D.; Rodriguez, D.; Bonewald, L.F.; Li, Z.; Ruffoni, D.; Müller, R.; Kesavan, C.; Sheng, M.H.-C. Osteocyte-derived insulin-like growth factor I is essential for determining bone mechanosensitivity. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2013, 305, E271–E281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Temiyasathit, S.; Tang, W.J.; Leucht, P.; Anderson, C.T.; Monica, S.D.; Castillo, A.B.; Helms, J.A.; Stearns, T.; Jacobs, C.R. Mechanosensing by the Primary Cilium: Deletion of Kif3A Reduces Bone Formation Due to Loading. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grimston, S.K.; Watkins, M.P.; Brodt, M.D.; Silva, M.J.; Civitelli, R. Enhanced Periosteal and Endocortical Responses to Axial Tibial Compression Loading in Conditional Connexin43 Deficient Mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, L.; Shim, J.W.; Dodge, T.R.; Robling, A.G.; Yokota, H. Inactivation of Lrp5 in osteocytes reduces Young’s modulus and responsiveness to the mechanical loading. Bone 2013, 54, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kesavan, C.; Wergedal, J.E.; Lau, K.-H.W.; Mohan, S. Conditional disruption of IGF-I gene in type 1α collagen-expressing cells shows an essential role of IGF-I in skeletal anabolic response to loading. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2011, 301, E1191–E1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xiao, Z.; Dallas, M.; Qiu, N.; Nicolella, D.; Cao, L.; Johnson, M.; Bonewald, L.; Quarles, L.D. Conditional deletion ofPkd1in osteocytes disrupts skeletal mechanosensing in mice. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 2418–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castillo, A.B.; Blundo, J.T.; Chen, J.C.; Lee, K.L.; Yereddi, N.R.; Jang, E.; Kumar, S.; Tang, W.J.; Zarrin, S.; Kim, J.-B.; et al. Focal Adhesion Kinase Plays a Role in Osteoblast Mechanotransduction In Vitro but Does Not Affect Load-Induced Bone Formation In Vivo. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, H.M. Bone’s mechanostat: A 2003 update. Anat. Rec. Part A Discov. Mol. Cell. Evol. Biol. 2003, 275A, 1081–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buarque de Gusmão, C.V.; Mariolani, J.R.; Belangero, W.D. Mechanotransduction and Osteogenesis. In Osteogenesis; Lin, Y., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- You, J.; Yellowley, C.E.; Donahue, H.J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Jacobs, C.R. Substrate Deformation Levels Associated With Routine Physical Activity Are Less Stimulatory to Bone Cells Relative to Loading-Induced Oscillatory Fluid Flow. J. Biomech. Eng. 2000, 122, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harle, J.; Salih, V.; Knowles, J.C.; Mayia, F.; Olsen, I. Effects of therapeutic ultrasound on osteoblast gene expression. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2001, 12, 1001–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buarque de Gusmão, C.V.; Belangero, W.D. How Do Bone Cells Sense Mechanical Loading? Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2015, 44, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, W.H.-S.; Sun, J.-S.; Chang, S.-P.; Lin, J.C. Study of thermal effects of ultrasound stimulation on fracture healing. Bioelectromagnetics 2002, 23, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, L.R. The stimulation of bone growth by ultrasound. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 1983, 101, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, T.; Harada, Y.; Imura, K.; Iwabuchi, S.; Murai, J.; Hiramatsu, K.; Myoui, A.; Yoshikawa, H.; Tsumaki, N. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound increases bone ingrowth into porous hydroxyapatite ceramic. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2007, 25, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yoshinori, A.; Paul, F.; Shen, H.; Chen, J.; Sotome, S.; Liu, Z.; Shinomiya, K. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound prompts tissue-engineered bone formation after implantation surgery. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2007, 127, 669–674. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, C.F.; Fau, C.C.; Yeung, H.Y.; Fau, Y.H.; Lee, K.M.; Qin, L.; Li, G.; Leung, K.S.; Hu, Y.Y.; Cheng, J.C.Y. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound enhances posterior spinal fusion implanted with mesenchymal stem cells-calcium phosphate composite without bone grafting. Spine 2011, 36, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cao, H.; Feng, L.; Wu, Z.; Hou, W.; Li, S.; Hao, Y.; Wu, L. Effect of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on the biological behavior of osteoblasts on porous titanium alloy scaffolds: An in vitro and in vivo study. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 80, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yang, D.; Wei, X.; Guo, S.; Wang, N.; Tang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Shen, S.; Shi, L.; Li, X.; et al. Fabrication of piezoelectric porous BaTiO3 scaffold to repair large segmental bone defect in sheep. J. Biomater. Appl. 2020, 35, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Guo, Z.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Gao, P.; Xiao, X.; Wu, J.; Shen, C.; Jiao, Y.; Hou, W. Electroactive barium titanate coated titanium scaffold improves osteogenesis and osseointegration with low-intensity pulsed ultrasound for large segmental bone defects. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 5, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronick, J.A.; Assanah, F.; Piscopo, N.; Kutes, Y.; Vyas, V.; Nair, L.S.; Huey, B.D.; Khan, Y. Mechanically Loading Cell/Hydrogel Constructs with Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound for Bone Repair. Tissue Eng. Part A 2018, 24, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, W.; Liu, X.; Zhu, M.; Sun, T.; Peng, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Feng, B.; Zhi, W.; Weng, J.; et al. Study of bilineage differentiation of human-bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in oxidized sodium alginate/N-succinyl chitosan hydrogels and synergistic effects of RGD modification and low-intensity pulsed ultrasound. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 2518–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.-K.; Huang, W.-T.; Liu, B.-S.; Li, S.-M.; Chen, H.-T.; Chang, C.-J. Effects of Near-Field Ultrasound Stimulation on New Bone Formation and Osseointegration of Dental Titanium Implants In Vitro and In Vivo. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2011, 37, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagasaki, R.; Mukudai, Y.; Yoshizawa, Y.; Nagasaki, M.; Shiogama, S.; Suzuki, M.; Kondo, S.; Shintani, S.; Shirota, T. A Combination of Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound and Nanohydroxyapatite Concordantly Enhances Osteogenesis of Adipose-Derived Stem Cells from Buccal Fat Pad. Cell Med. 2015, 7, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Das, R.; Curry, E.J.; Le, T.T.; Awale, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Contreras, J.; Bednarz, C.; Millender, J.; Xin, X.; et al. Biodegradable nanofiber bone-tissue scaffold as remotely-controlled and self-powering electrical stimulator. Nano Energy 2020, 76, 105028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, Y.-T.; Huang, Y.-J.; Wu, H.-H.; Liu, Y.-A.; Liu, Y.-S.; Lee, O.K. Osteocalcin Mediates Biomineralization during Osteogenic Maturation in Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, A.M.D.; Batra, N.N.; Shivaram, G.; Kwon, R.Y.; You, L.; Kim, C.H.; Rodriguez, J.; Jair, K.; Jacobs, C.R. The role of actin cytoskeleton in oscillatory fluid flow-induced signaling in MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2007, 292, C1830–C1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzer, G.; Manske, S.L.; Chan, M.E.; Chiang, F.-P.; Rubin, C.T.; Frame, M.D.; Judex, S. Separating Fluid Shear Stress from Acceleration during Vibrations In Vitro: Identification of Mechanical Signals Modulating the Cellular Response. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2012, 5, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, H.; Shi, Z.; Cai, X.; Yang, X.; Zhou, C. The combination of PLLA/PLGA/PCL composite scaffolds integrated with BMP-2-loaded microspheres and low-intensity pulsed ultrasound alleviates steroid-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murshed, M. Mechanism of Bone Mineralization. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a031229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouwkema, J.; Rivron, N.C.; van Blitterswijk, C. Vascularization in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Cai, Y.; Hu, H.; Guo, P.; Xin, Z. Enhanced regeneration of large cortical bone defects with electrospun nanofibrous membranes and low-intensity pulsed ultrasound. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, K.; Trujillo-de Santiago, G.; Alvarez, M.M.; Tamayol, A.; Annabi, N.; Khademhosseini, A. Synthesis, properties, and biomedical applications of gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) hydrogels. Biomaterials 2015, 73, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chai, Q.; Jiao, Y.; Yu, X. Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications: Their Characteristics and the Mechanisms behind Them. Gels 2017, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suvarnapathaki, S.; Wu, X.; Lantigua, D.; Nguyen, M.; Camci-Unal, G. Hydroxyapatite-Incorporated Composite Gels Improve Mechanical Properties and Bioactivity of Bone Scaffolds. Macromol. Biosci. 2020, 20, e2000176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvarnapathaki, S.; Nguyen, M.A.; Wu, X.; Nukavarapu, S.P.; Camci-Unal, G. Synthesis and characterization of photocrosslinkable hydrogels from bovine skin gelatin. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 13016–13025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, J.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Yu, Y. Role of bone morphogenetic protein-2 in osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 4230–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poon, B.; Kha, T.; Tran, S.; Dass, C.R. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 and bone therapy: Successes and pitfalls. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2016, 68, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijdicks, C.A.; Virdi, A.S.; Sena, K.; Sumner, D.R.; Leven, R.M. Ultrasound Enhances Recombinant Human BMP-2 Induced Ectopic Bone Formation in a Rat Model. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2009, 35, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Walsh, K.; Suvarnapathaki, S.; Lantigua, D.; McCarthy, C.; Camci-Unal, G. Mineralized paper scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, T.; Hoff, B.; Suvarnapathaki, S.; Lantigua, D.; McCarthy, C.; Wu, B.; Camci-Unal, G. Mineralized Hydrogels Induce Bone Regeneration in Critical Size Cranial Defects. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, 2001101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Castro, N.J.; Li, J.; Keidar, M.; Zhang, L.G. Greater osteoblast and mesenchymal stem cell adhesion and proliferation on titanium with hydrothermally treated nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite/magnetically treated carbon nanotubes. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2012, 12, 7692–7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angle, S.R.; Sena, K.; Sumner, D.R.; Virdi, A.S. Osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow stromal cells by various intensities of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound. Ultrasonics 2011, 51, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Lv, H.; Li, Z.; Tang, P.; Wang, Y. Effect of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on distraction osteogenesis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2018, 13, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashardoust Tajali, S.; Houghton, P.M.; Joy, C.; Grewal, R. Effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound therapy on fracture healing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 91, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schandelmaier, S.; Kaushal, A.; Lytvyn, L.; Heels-Ansdell, D.; Siemieniuk, R.A.C.; Agoritsas, T.; Guyatt, G.H.; Vandvik, P.O.; Couban, R.; Mollon, B.; et al. Low intensity pulsed ultrasound for bone healing: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMJ 2017, 356, j656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighton, R.; Watson, J.T.; Giannoudis, P.; Papakostidis, C.; Harrison, A.; Steen, R.G. Healing of fracture nonunions treated with low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury 2017, 48, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, M.A.; Camci-Unal, G. Unconventional Tissue Engineering Materials in Disguise. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantigua, D.; Kelly, Y.N.; Unal, B.; Camci-Unal, G. Engineered Paper-Based Cell Culture Platforms. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017, 6, 1700619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palanisamy, P.; Alam, M.; Li, S.; Chow, S.K.H.; Zheng, Y.-P. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Stimulation for Bone Fractures Healing. J. Ultrasound Med. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, A.R.; Laurencin, C.T.; Nukavarapu, S.P. Bone tissue engineering: Recent advances and challenges. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 40, 363–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Source | Cell Line | Gene Deletion | Effect of Gene Deletion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arthur et al. (2020) [47] | Osx-Cre | EfnB1 | Soft callus and remodeling phases of fracture healing were delayed. |

| Zhang et al. (2011) [48] | OC-Cre | Cx43 | Mice with Cx43 deficient osteoblasts showed significantly greater anabolic response to mechanical loading. |

| McBride-Gagyi et al. (2015) [49] | UBC-Cre OSX-Cre Vec-Cre | BMP-2 | Endothelial cells and osteoblasts are not a source of BMP-2 for endochondral fracture healing. Non-endochondral fracture healing does not depend on BMP-2. |

| Phillips et al. (2008) [50] | Colα1-Cre | beta1 integrin | The absence of mechanical loading typically causes changes to cortical bone geometry. Deletion of Beta1 integrins resulted in fewer changes to cortical geometry proving that Beta1 integrins are involved in mechanotransduction. |

| Shekaran et al. (2014) [51] | Twist-Cre Osterix-Cre Osteocalcin-Cre | Beta1 integrin | Twist-Cre: Mice had severe skeletal impairment and died at birth. Beta1 is responsible for skeletal ossification. Osterix-Cre: Beta1 deletion impacted incisor eruption and the formation of perinatal bone. Osteocalcin-Cre: Beta 1 deletion had only minor skeletal effects. |

| Delgado-Calle et al. (2016) [52] | (DMP1)-8kb- expressing cells | Parathyroid hormone receptor (Pth1r) | Pth1r regulates basal bone resorption levels and is required for anabolic actions of mechanical loading. |

| Iura et al. (2015) [53] | Col1-CreERTM | Bmpr1a | Lower Bmpr1a signaling makes osteoblasts more sensitive to mechanical loading and improves the mechanical properties of bone. |

| Grimston et al. (2009) [54] | Col-Cre | Gja1 | Deletion of Gja1 reduces the anabolic response to mechanical loading. |

| Lawson et al. (2021) [55] | Osx-CreERT2 | Wnt1 and Wnt7b | Wnt ligands are required to maintain homeostasis in adult bones and control the anabolic response to mechanical loading. |

| Mahon et al. (2015) [56] | Col1α2-Cre | (miR)17–92 | The periosteal bone response to mechanical strain is reduced without (miR)17–92. (miR) 17–92 plays a role in regulating type 1 collagen during periosteal bone formation. |

| Lau et al. (2015) [57] | DMP1-Cre | Igf1 | Igf1 is required for the anabolic response to mechanical loading, but it is not required for bone repletion. |

| Lau et al. (2013) [58] | DMP1-Cre | Igf1 | Deletion of Igf1 prevents the activation of Wnt signaling in response to a mechanical load. Igf1 impacts the mechanosensitivity of bone. |

| Temiyasathit et al. (2012) [59] | Colα(1)2.3-Cre | Kif3a | Deletion of Kifa3 leads to decreased bone formation suggesting that primary cilia are mechanosensors for bone. |

| Grimston et al. (2012) [60] | DM1-Cre | Gja1 | Deletion of Gja1 results in Cx43 deficiency and increases the periosteal and endocortical responses of bone to axial compression. |

| Zhao et al. (2013) [61] | Dmp-Cre | Lrp5 | Deletion of Lrp5 decreases mechanoresponsiveness and bone mass, and increases elasticity. |

| Kesavan et al. (2011) [62] | Col1α2-Cre | Igf1 | Igf1 is required for the transduction of a mechanical signal into a signal for the anabolism of bone. |

| Xiao et al. (2011) [63] | Dmp1-Cre | Pkd1 | Pkd1 is required to initiate the anabolic response to mechanical loading of osteoblasts and osteocytes. |

| Castillo et al. (2012) [64] | FAK−/− clone ID8 | FAK | FAK is required for mechanical signaling in vitro but not in vivo. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCarthy, C.; Camci-Unal, G. Low Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound for Bone Tissue Engineering. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1488. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi12121488

McCarthy C, Camci-Unal G. Low Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound for Bone Tissue Engineering. Micromachines. 2021; 12(12):1488. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi12121488

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCarthy, Colleen, and Gulden Camci-Unal. 2021. "Low Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound for Bone Tissue Engineering" Micromachines 12, no. 12: 1488. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi12121488

APA StyleMcCarthy, C., & Camci-Unal, G. (2021). Low Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound for Bone Tissue Engineering. Micromachines, 12(12), 1488. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi12121488