Aligning Minds in Spasticity Care—A Two-Phase Delphi-Dialogue Study of Patients and Professionals in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objectives

2.1. General Aim

2.2. Specific Objectives

- To systematically capture and compare patient and professional experiences in CBI rehabilitation, identifying areas of convergence and divergence regarding current models of care, communication practices, and perceived quality of services.

- To assess attitudes toward digital and hybrid rehabilitation models, including tele-rehabilitation and remote communication tools, from both patient and professional perspectives.

- To evaluate the feasibility of targeted improvement strategies for CBI rehabilitation services through an expert-driven Real-Time Delphi process, prioritizing interventions that are realistic and actionable within current healthcare settings.

3. Results

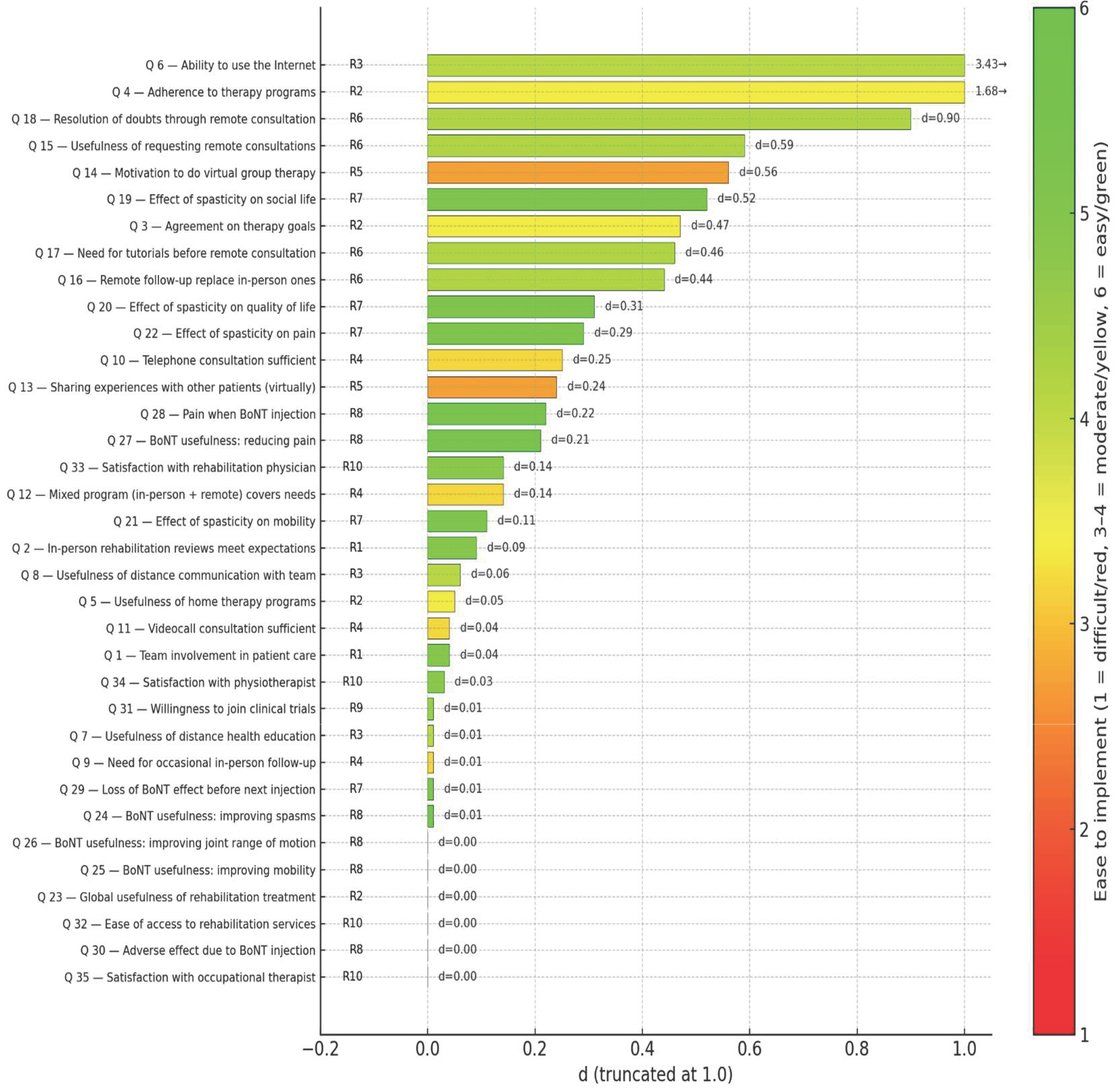

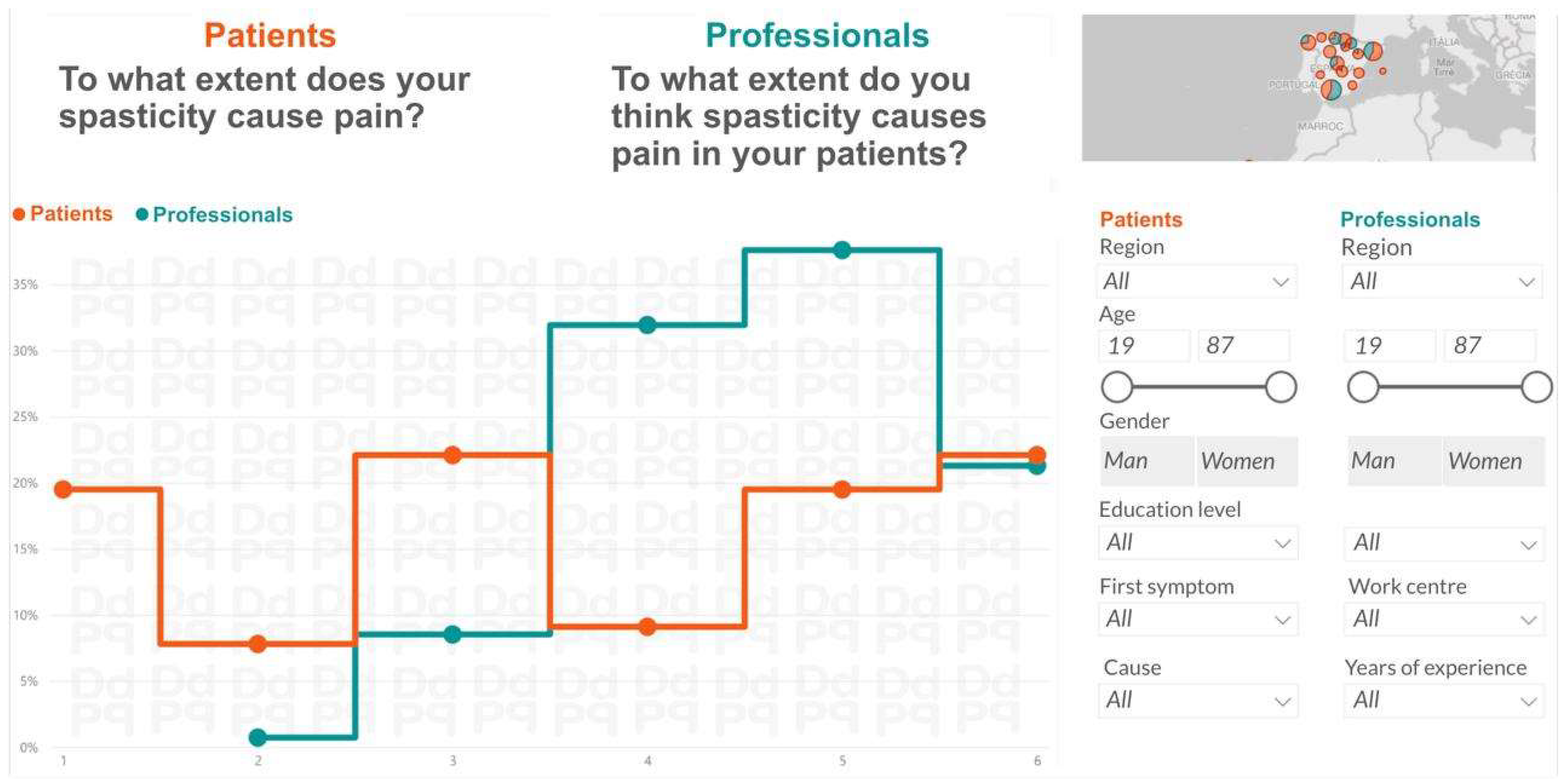

3.1. Comparison of Experiences Between Patients and Professionals

- SDI = |μpat − μpro|/√[(σ2pat + σ2pro)/2];

- ΔA = |(Apat − Apro)/Min (Apat; Apro)|;

- μpat, μpro: for patients and professionals;

- σpat, σpro: standard deviations for patients and professionals;

- Apat, Apro: Sum of answers 5 and 6 for patients and professionals.

- d = 0: perfect alignment—similar perceptions and comparable high agreement.

- d increases as the difference in perception grows and high-agreement convergence decreases, divergence rises.

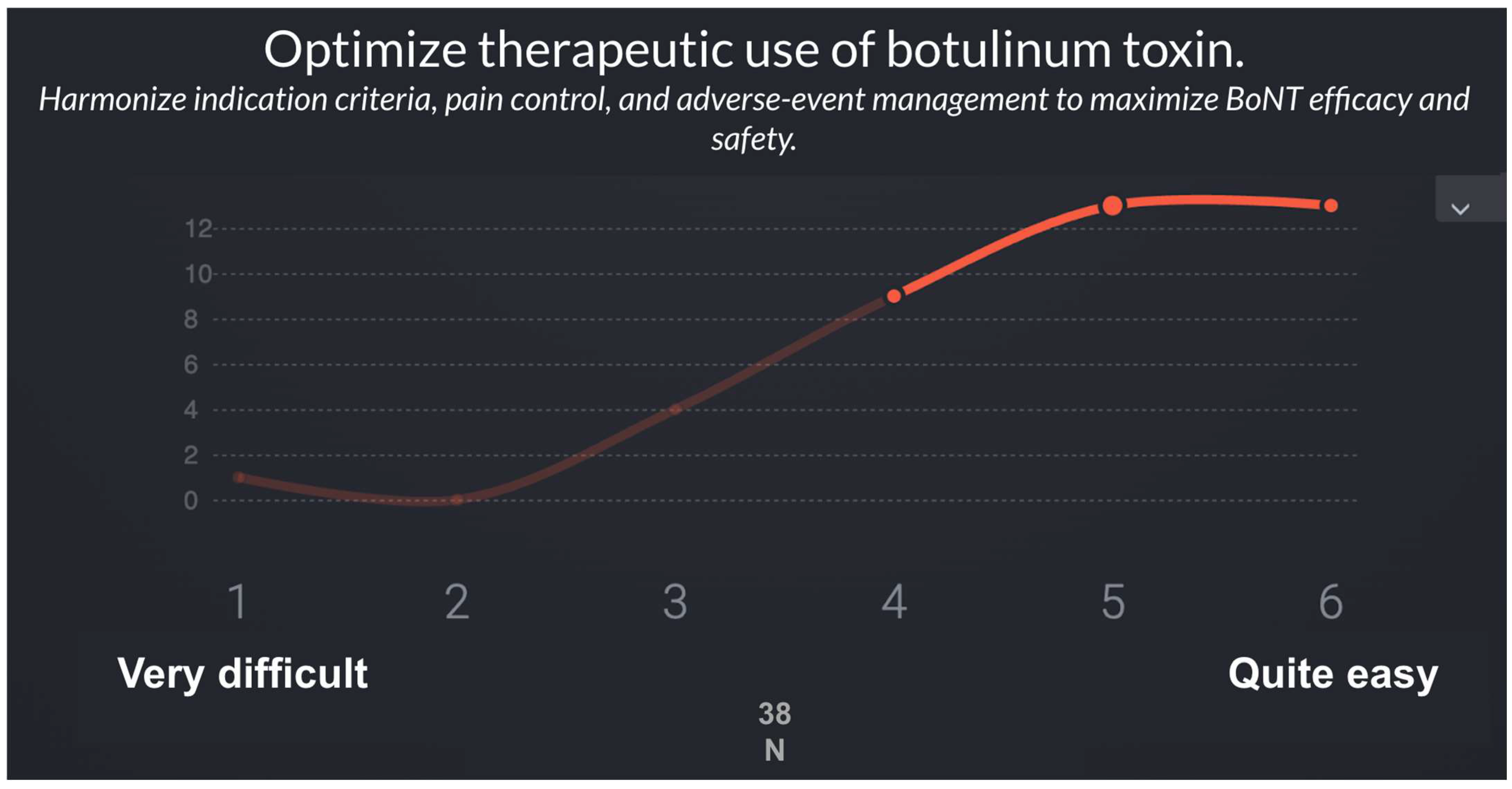

3.2. Second Phase: Validation and Prioritization of Recommendations

3.3. Final Proposal: Innovation Domains (ID) in Spasticity Rehabilitation

4. Discussion

4.1. Contribution Beyond Existing Evidence

4.2. Divergences and Convergences Between Patients and Professionals

4.3. Access and Communication Gaps

4.4. Integrated Interpretation of Tele-Rehabilitation, Education, and Communication

4.5. Therapeutic Personalization and Optimization of BoNT

4.6. Methodological Contribution and Replicability of the DDPP Approach

5. Conclusions

6. Materials and Methods

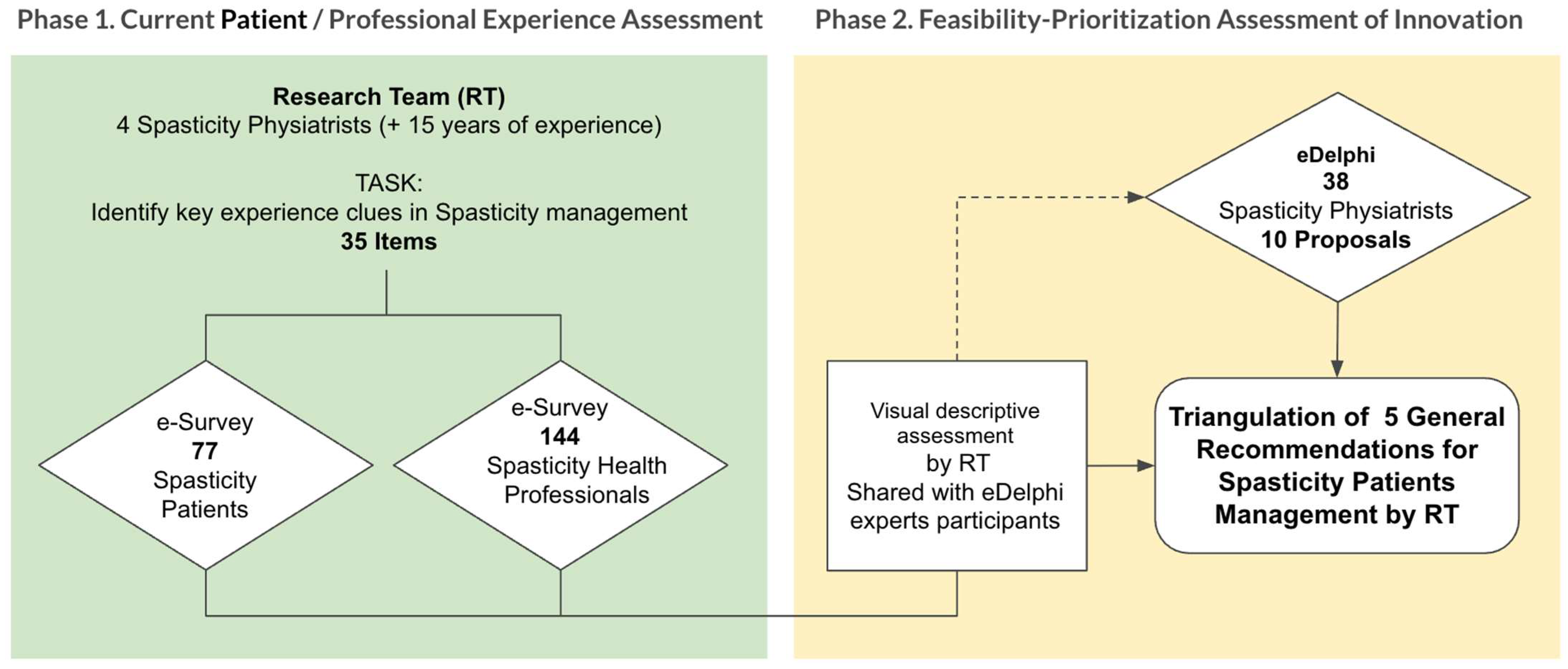

6.1. Study Design and Context

6.2. Participants and Inclusion Criteria

6.2.1. General Inclusion Criteria

6.2.2. Data Collected

6.3. Questionnaires

- Profile and characterization variables:

- Common items:

- -

- Eighteen questions addressing shared domains such as access to rehabilitation services, adequacy of clinical information, involvement of the multidisciplinary rehabilitation team, use of hybrid or tele-rehabilitation models, and preferred communication channels (Table 3).

- Condition-specific items:

- -

- Seventeen questions focused on spasticity care, including botulinum toxin (BoNT) treatment itineraries (perceived utility, waning effects, adverse events) and the functional and social impact of spasticity.

6.4. Procedure

- Phase 1: Surveys

- Phase 2: Real-Time Delphi

- Phase 1 (Surveys)

- -

- Primary outcome: alignment gap between patients and professionals across domains: access, information, BoNT treatment, communication and follow-up.

- -

- Indicators: mean scores, proportion of agreement (≥5/6), and Synthetic Indicator (d) combining the standardized difference between perceptions and the agreement gap.

- Phase 2 (Real-Time Delphi)

- -

- Indicators: mean (μ), standard deviation (σ), median (Med) and interquartile range (IQR).

- -

- Operational output: prioritized list of recommendations by feasibility (μ, Med, IQR) with complementary notes for clinical implementation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dressler, D.; Bhidayasiri, R.; Bohlega, S.; Chana, P.; Chien, H.F.; Chung, T.M.; Colosimo, C.; Ebke, M.; Fedoroff, K.; Frank, B.; et al. Defining spasticity: A new approach considering current movement disorders terminology and botulinum toxin therapy. J. Neurol. 2018, 265, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, A.; Chakravarty, A. Spasticity mechanisms—For the clinician. Front. Neurol. 2010, 1, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Tan, S. Prevalence and risk factors for spasticity after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2021, 11, 616097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biering-Sørensen, B.; Stevenson, V.; Bensmail, D.; Grabljevec, K.; Martínez Moreno, M.; Pucks-Faes, E.; Wissel, J.; Zampolini, M. European expert consensus on improving patient selection for the management of disabling spasticity with intrathecal baclofen and/or botulinum toxin type A. J. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 54, jrm00241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Luo, A.; Yu, J.; Qian, C.; Liu, D.; Hou, M.; Ma, Y. Quantitative assessment of spasticity: A narrative review of novel approaches and technologies. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1121323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karri, J.; Mas, M.F.; Francisco, G.E.; Li, S. Practice patterns for spasticity management with phenol neurolysis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 49, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korupolu, R.; Malik, A.; Pemberton, E.; Stampas, A.; Li, S. Phenol neurolysis in people with spinal cord injury: A descriptive study. Spinal Cord. Ser. Cases 2022, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippetti, M.; Tamburin, S.; Di Censo, R.; Adamo, M.; Manera, E.; Ingrà, J.; Mantovani, E.; Facciorusso, S.; Battaglia, M.; Baricich, A.; et al. Role of diagnostic nerve blocks in the goal-oriented treatment of spasticity with botulinum toxin type A: A case-control study. Toxins 2024, 16, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, P.; Mills, P.B.; Reebye, R.; Vincent, D. Cryoneurotomy as a percutaneous mini-invasive therapy for the treatment of the spastic limb: Case presentation, review of the literature, and proposed approach for use. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2019, 1, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R.; Hashemi, M.; Schatz, L.; Winston, P. Multisite treatment with percutaneous cryoneurolysis for the upper and lower limb in long-standing post-stroke spasticity. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 60, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, A.; Lourenço, C.; Ermida, F.N.; Costa, A.; Carvalho, J.L. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous radiofrequency thermal neuroablation for the treatment of adductor and rectus femoris spasticity. Cureus 2023, 15, e33422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Villaverde, S.; Formigo-Couceiro, J.; Martin-Mourelle, R.; Montoto-Marques, A. Safety and Effectiveness of Thermal Radiofrequency Applied to the Musculocutaneous Nerve for Patients with Spasticity. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1369947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, A.; Bagnato, S.; Boccagni, C.; Romano, M.C.; Galardi, G. Efficacy of intra-articular injection of botulinum toxin type A in refractory hemiplegic shoulder pain. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 1034–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-L.; Zhang, X.-J.; Li, H.; Chen, L. Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy on Spasticity After Upper Motor Neuron Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 101, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otero-Luis, I.; Gómez-Santaclara, M.; Vidal-García, E.; de la Fuente-García, A. Effectiveness of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy in the Treatment of Spasticity of Different Aetiologies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.; Rosewilliam, S.; Soundy, A. Shared decision making within goal setting in rehabilitation settings: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagen, J.S.; Kjeken, I.; Habberstad, A.; Linge, A.D.; Simonsen, A.E.; Lyken, A.D.; Irgens, E.L.; Framstad, H.; Lyby, P.S.; Klokkerud, M.; et al. Patient involvement in the rehabilitation process is associated with improvement in function and goal attainment: Results from an explorative longitudinal study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, J.; Karam, P.; Forestier, A.; Loze, J.Y.; Bensmail, D. Botulinum toxin use in patients with post-stroke spasticity: A nationwide French database study. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1245228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduzco-Gutierrez, M.; Raghavan, P.; Pruente, J.; Moon, D.; List, C.M.; Hornyak, J.E.; Gul, F.; Deshpande, S.; Biffl, S.; Al Lawati, Z.; et al. AAPM&R consensus guidance on spasticity assessment and management. PM&R 2024, 16, 864–887. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.; Alfaro, S.; Verduzco-Gutierrez, M.; Kwasnica, C. Multidisciplinary collaborative consensus statement on barriers and solutions to care access for spasticity patients. PM&R 2024, 16, 278–286. [Google Scholar]

- Francisco, G.E.; Balbert, A.; Bavikatte, G.; Bensmail, D.; Carda, S.; Deltombe, T.; Draulans, N.; Escaldi, S.; Gross, R.; Jacinto, J.; et al. A practical guide to optimizing the benefits of post-stroke spasticity interventions with botulinum toxin A: An international group consensus. J. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 53, Jrm00134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, N.; Leo, F.; Chisari, C.; Dalise, S. Long-term management of post-stroke spasticity with botulinum toxin: A Retrospective Study. Toxins 2024, 16, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, T.A.; Atkinson, T.M.; Latella, L.E.; Rogers, M.; Morrissey, D.; DeRosa, A.P.; Parker, P.A. Promoting patient participation in healthcare interactions through communication-skills training: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdat, S.; Hamzehgardeshi, L.; Hessam, S.; Hamzehgardeshi, Z. Patient involvement in healthcare decision making: A review. Iran. Red. Crescent Med. J. 2014, 16, e12454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plewnia, A.; Bengel, J.; Körner, M. Patient-centeredness and its impact on satisfaction and treatment outcomes in medical rehabilitation. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 2063–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, S.; Morris, G.; Smith, M.J. Ultrasound image guided injection of botulinum toxin for the management of spasticity: A Delphi study to develop recommendations for a scope of practice, competency, and governance framework. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2023, 5, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wissel, J.; Ri, S.; Kivi, A. Early versus late injections of Botulinumtoxin type A in post-stroke spastic movement disorder: A literature review. Toxicon 2023, 229, 107150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.C.; Deutsch, J.; Holdsworth, L.; Kaplan, S.; Kosakowski, H.; Latz, R.; McNeary, L.; O’Neil, J.; Ronzio, O.; Sanders, K.; et al. Telerehabilitation in physical therapist practice: A clinical practice guideline. Phys. Ther. 2024, 104, pzae023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, S.; Cacciante, L.; Cieślik, B.; Turolla, A.; Agostini, M.; Kiper, P.; Picelli, A.; RIN_TR_Group. Telerehabilitation for Neurological Motor Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Quality of Life, Satisfaction, and Acceptance in Stroke, Multiple Sclerosis, and Parkinson’s Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.S.; Ryu, J.; Jin, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, M. Long-Term Enhancement of Botulinum Toxin Injections for Post-Stroke Spasticity by Use of Stretching Exercises-A Randomized Controlled Trial. Toxins 2024, 16, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topol, E. Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1541644632. [Google Scholar]

| Patients | Professionals | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | μ | σ | A | Μ | σ | A | SDI | d | |

| Q 6 | Ability to use the Internet | 4.4 | 1.82 | 58.5 | 3.3 | 0.94 | 10.6 | 0.76 | 3.43 |

| Q 4 | Adherence to therapy programs | 4.4 | 1.42 | 57.2 | 3.6 | 0.93 | 16.3 | 0.67 | 1.68 |

| Q 18 | Resolution of doubts through remote consultation | 2.9 | 1.48 | 11.7 | 3.7 | 1.13 | 29 | 0.61 | 0.90 |

| Q 15 | Usefulness of requesting remote consultations | 3.4 | 1.66 | 26 | 4.3 | 1.33 | 51.8 | 0.60 | 0.59 |

| Q 14 | Motivation to do virtual group therapy | 3.2 | 1.68 | 23.4 | 4.2 | 1.20 | 42.5 | 0.69 | 0.56 |

| Q 19 | Effect of spasticity on social life | 4.5 | 1.22 | 55.9 | 5.4 | 0.73 | 88.6 | 0.89 | 0.52 |

| Q 3 | Agreement on therapy goals | 4.1 | 1.64 | 44.2 | 5 | 0.88 | 74.5 | 0.69 | 0.47 |

| Q 17 | Need for tutorials before remote consultation | 3.4 | 1.72 | 31.2 | 4.4 | 1.32 | 53.2 | 0.65 | 0.46 |

| Q 16 | Remote follow-up can replace in-person ones | 2.6 | 1.59 | 15.6 | 3.5 | 1.40 | 26.9 | 0.60 | 0.44 |

| Q 20 | Effect of spasticity on quality of life | 4.9 | 1.05 | 66.3 | 5.6 | 0.65 | 91.5 | 0.81 | 0.31 |

| Q 22 | Effect of spasticity on pain | 3.7 | 1.81 | 41.6 | 4.7 | 0.92 | 58.9 | 0.70 | 0.29 |

| Q 10 | Telephone consultation sufficient | 3.2 | 1.55 | 18.2 | 2.9 | 1.16 | 8.5 | 0.22 | 0.25 |

| Q 13 | Sharing experiences with other patients (virtually) | 3.6 | 1.76 | 33.8 | 4.4 | 1.05 | 48.2 | 0.55 | 0.24 |

| Q 28 | Pain when BoNT injection | 2.8 | 1.64 | 18.2 | 3.3 | 1.11 | 11.3 | 0.36 | 0.22 |

| Q 27 | BoNT usefulness: reducing pain | 4.3 | 1.71 | 53.3 | 4.9 | 0.83 | 78.7 | 0.45 | 0.21 |

| Q 12 | Mixed program (in-person + remote) covers needs | 4.1 | 1.65 | 44.2 | 4.7 | 1.08 | 58.8 | 0.43 | 0.14 |

| Q 33 | Satisfaction with rehabilitation physician | 5.2 | 1.30 | 81.8 | 4.7 | 0.81 | 63.1 | 0.46 | 0.14 |

| Q 21 | Effect of spasticity on mobility | 4.6 | 1.41 | 58.5 | 5 | 0.76 | 77.3 | 0.35 | 0.11 |

| Q 2 | In-person rehabilitation reviews meet expectations | 4.8 | 1.36 | 67.6 | 4.5 | 0.80 | 51.1 | 0.27 | 0.09 |

| Q 8 | Usefulness of distance communication with team | 4.2 | 1.65 | 45.5 | 4 | 1.12 | 32.6 | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| Q 5 | Usefulness of home therapy programs | 4.2 | 1.54 | 46.8 | 4.6 | 1.07 | 53.9 | 0.30 | 0.05 |

| Q 1 | Team involvement in patient care | 5 | 1.23 | 76.7 | 5.3 | 0.77 | 86.5 | 0.29 | 0.04 |

| Q 11 | Videocall consultation sufficient | 3.5 | 1.65 | 27.3 | 3.4 | 1.22 | 17.8 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Q 34 | Satisfaction with physiotherapist | 4.9 | 1.48 | 72.8 | 4.6 | 0.85 | 65.3 | 0.25 | 0.03 |

| Q 24 | BoNT usefulness: improving spasms | 4.8 | 1.54 | 65 | 4.9 | 0.95 | 75.2 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Q 29 | Loss of BoNT effect before next injection | 4.4 | 1.58 | 58.5 | 4.5 | 0.98 | 50.4 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Q 9 | Need for occasional in-person follow-up | 4.4 | 1.48 | 57.2 | 4.6 | 0.95 | 61 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| Q 7 | Usefulness of distance health education | 3.8 | 1.61 | 39 | 4.1 | 1.14 | 40.4 | 0.22 | 0.01 |

| Q 31 | Willingness to join clinical trials | 4.2 | 1.94 | 55.9 | 4.3 | 1.13 | 50.3 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Q 35 | Satisfaction with occupational therapist | 4.3 | 1.85 | 58.5 | 4.4 | 1.13 | 55.1 | 0.07 | 0.00 |

| Q 30 | Adverse effect due to BoNT injection | 1.8 | 1.43 | 76.6 | 2 | 0.80 | 77.3 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| Q 32 | Ease of access to rehabilitation services | 4 | 1.91 | 49.4 | 4.2 | 1.08 | 49.7 | 0.13 | 0.00 |

| Q 23 | Global usefulness of rehabilitation treatment | 5.3 | 1.10 | 83.1 | 5.2 | 0.84 | 83.7 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| Q 25 | BoNT usefulness: improving mobility | 4.6 | 1.62 | 65 | 4.8 | 1.01 | 65.2 | 0.15 | 0.00 |

| Q 26 | BoNT usefulness: improving joint range of motion | 4.8 | 1.44 | 67.6 | 4.8 | 0.91 | 70.2 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| No. | Recommendation | Linked Survey Items | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Strengthen interdisciplinary coordination in rehabilitation care | 1–2 | Formalize team workflows to ensure coherent, goal-oriented care during hospitalization and outpatient care. |

| 2 | Ensure adherence and continuity of rehabilitation programs | 3–5, 23 | Use shared goal-setting, structured home programs, and tailored education/monitoring to sustain adherence over time. |

| 3 | Promote digital health literacy and safe technology use in rehabilitation | 6–8 | Provide training and support for patients and staff to integrate tele-rehabilitation, remote education, and secure communication. |

| 4 | Implement hybrid follow-up models (in-person + telemedicine) | 9–12 | Implement flexible mixed care pathways that preserve therapeutic quality while optimizing time and resources. |

| 5 | Reinforce the social and motivational dimension of virtual therapy | 13–14 | Add structured peer-interaction and group dynamics in digital environments to enhance engagement and motivation. |

| 6 | Standardize remote follow-up with protocols and support tools | 15–18 | Define pre-visit tutorials, operational protocols, and patient-reported feedback loops to evaluate impact and satisfaction. |

| 7 | Develop predictive models of spasticity course | 19–22, 29 | Build analytics linking spasticity severity, function, and BoNT waning to anticipate needs and personalize follow-up. |

| 8 | Optimize therapeutic use of botulinum toxin | 24–28, 30 | Harmonize indication criteria, pain control, and adverse-event management to maximize BoNT efficacy and safety. |

| 9 | Foster patient participation in research and continuous improvement | 31 | Facilitate enrollment in clinical studies and co-design initiatives to accelerate evidence generation and validation. |

| 10 | Improve accessibility and global satisfaction with rehabilitation services | 32–35 | Address access barriers and monitor satisfaction across disciplines to strengthen quality and continuity of care. |

| N | Question | μ | σ | Med | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R8 | Optimize therapeutic use of botulinum toxin | 5.3 | 1.0 | 5 | 1 |

| R7 | Develop predictive models of spasticity course | 5.1 | 0.9 | 5 | 1 |

| R1 | Strengthen interdisciplinary coordination in rehabilitation care | 4.9 | 1.2 | 5 | 1 |

| R10 | Improve accessibility and global satisfaction with rehabilitation services | 4.8 | 1.3 | 5 | 2 |

| R9 | Foster patient participation in research and continuous improvement | 4.5 | 1.2 | 5 | 2 |

| R6 | Standardize remote follow-up with protocols and support tools | 4.2 | 1.1 | 4 | 2 |

| R3 | Promote digital health literacy and safe technology use in rehab | 4.1 | 1.5 | 4 | 3 |

| R2 | Ensure adherence and continuity of rehabilitation programs | 3.4 | 1.3 | 4 | 2 |

| R4 | Implement hybrid follow-up models (in-person + telemedicine) | 3.2 | 1.4 | 3 | 2 |

| R5 | Reinforce the social and motivational dimension of virtual therapy | 2.7 | 1.3 | 2 | 3 |

| Variable | Distribution |

|---|---|

| Gender | Male: 57.1% (n = 44); Female: 42.9% (n = 33) |

| Education | Secondary/Vocational: 45.5%; University: 31.2%; Primary: 19.5%; No formal education: 3.9% |

| Living situation | Independent at home (51.9%);·Family caregiver (36.4%); Professional caregiver (3.9%); Supervised housing (3.9%); Nursing home (3.9%) |

| Etiology of spasticity | Ischemic stroke: 27.3%; Hemorrhagic stroke: 15.6%; Cerebral palsy: 11.7%; Multiple sclerosis: 10.4%; Spinal cord injury: 10.4%; Traumatic brain injury: 7.8%; Other: 16.9% |

| Time from symptom onset to diagnosis | <1 year: 32.5%; 1–5 years: 33.8%; 6–10 years: 11.7%; >10 years: 22.1% |

| Time from diagnosis to botulinum toxin treatment | <1 month: 11.7%; 1–3 months: 18.2%; 4–6 months: 20.8%; >6 months: 49.4% |

| Treatments received | Botulinum toxin: 85.9%; Physiotherapy: 57.8%; Occupational therapy: 31.2%; Orthoses: 28.1%; Oral medication: 20.3%; Nerve blocks: 12.5% |

| Employment impact | Previously employed: 62.3%; Currently employed: 22.1%; Work disability recognized: 57.1% (of which 54.5% due to spasticity) |

| Comorbidities | Chronic disease in addition to spasticity: 46.8% |

| Housing adaptation | Adapted: 57.1%; Not adapted: 42.9% |

| Variable | Distribution |

|---|---|

| Gender | Female: 77.3% (n = 109); Male: 22.7% (n = 32) |

| Professional category | PM&R physicians: 86.5%; Physiotherapists: 8.5%; Occupational therapists: 5% |

| Workplace | Referral hospital: 61%; Area/Secondary; hospital (~400 beds): 25.5%; Basic general; hospital (~200 beds): 5%; District hospital (~100 beds): 5.7%; Other: 2.8% |

| Experience in spasticity | <5 years: 17.7%; 6–10 years: 24.1%; 11–15 years: 18.4%; 15–20 years: 22%; >20 years: 17.7% |

| Experience in interventional management of spasticity | <5 years: 26.2%; 6–10 years: 28.4%; 11–15 years: 17.7%; 15–20 years: 16.3%; >20 years: 11.3% |

| Treatments used | Physiotherapy 95%; Botulinum toxin 90.1%; Orthoses 87.9%; Occupational therapy 67.4%; Oral medication 61%; Nerve blocks 37.6%; Intrathecal baclofen pump 24.1%; Shock wave therapy 19.9%; Radiofrequency 7.8% |

| Scientific activity | No publications: 41.8%; <5 publications: 41.1%; 5–30 publications: 12.8%; >30 publications: 4.3% |

| University teaching | Yes: 31.2%; No: 68.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bascuñana-Ambrós, H.; Formigo-Couceiro, J.; Climent-Barberá, J.M.; Guirao-Cano, L.; Catta-Preta, M.; Trejo-Omeñaca, A.; Monguet-Fierro, J.M. Aligning Minds in Spasticity Care—A Two-Phase Delphi-Dialogue Study of Patients and Professionals in Spain. Toxins 2026, 18, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010056

Bascuñana-Ambrós H, Formigo-Couceiro J, Climent-Barberá JM, Guirao-Cano L, Catta-Preta M, Trejo-Omeñaca A, Monguet-Fierro JM. Aligning Minds in Spasticity Care—A Two-Phase Delphi-Dialogue Study of Patients and Professionals in Spain. Toxins. 2026; 18(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleBascuñana-Ambrós, Helena, Jacobo Formigo-Couceiro, José Maria Climent-Barberá, Lluis Guirao-Cano, Michelle Catta-Preta, Alex Trejo-Omeñaca, and Josep Maria Monguet-Fierro. 2026. "Aligning Minds in Spasticity Care—A Two-Phase Delphi-Dialogue Study of Patients and Professionals in Spain" Toxins 18, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010056

APA StyleBascuñana-Ambrós, H., Formigo-Couceiro, J., Climent-Barberá, J. M., Guirao-Cano, L., Catta-Preta, M., Trejo-Omeñaca, A., & Monguet-Fierro, J. M. (2026). Aligning Minds in Spasticity Care—A Two-Phase Delphi-Dialogue Study of Patients and Professionals in Spain. Toxins, 18(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010056