Neurophysiological Assessment of F-Wave, M-Wave, and Cutaneous Silent Period in Patients with Caput-Pattern Cervical Dystonia at Waning and Peak Response Phases of Botulinum Toxin Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. F-Wave and M-Wave Measurements

2.2. Calculated F-Wave Parameters

2.3. Cutaneous Silent Period (CSP) Measurements

2.4. CSP Conduction Velocities

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

- 9 patients with LCap/TCap;

- 3 with LCap/TCap/ACap;

- 4 with LCap/TCap/RCap;

- 2 with TCap/ACap;

- 3 with TCap/RCap.

4.2. Botulinum Toxin Treatment Protocol

4.3. Methods

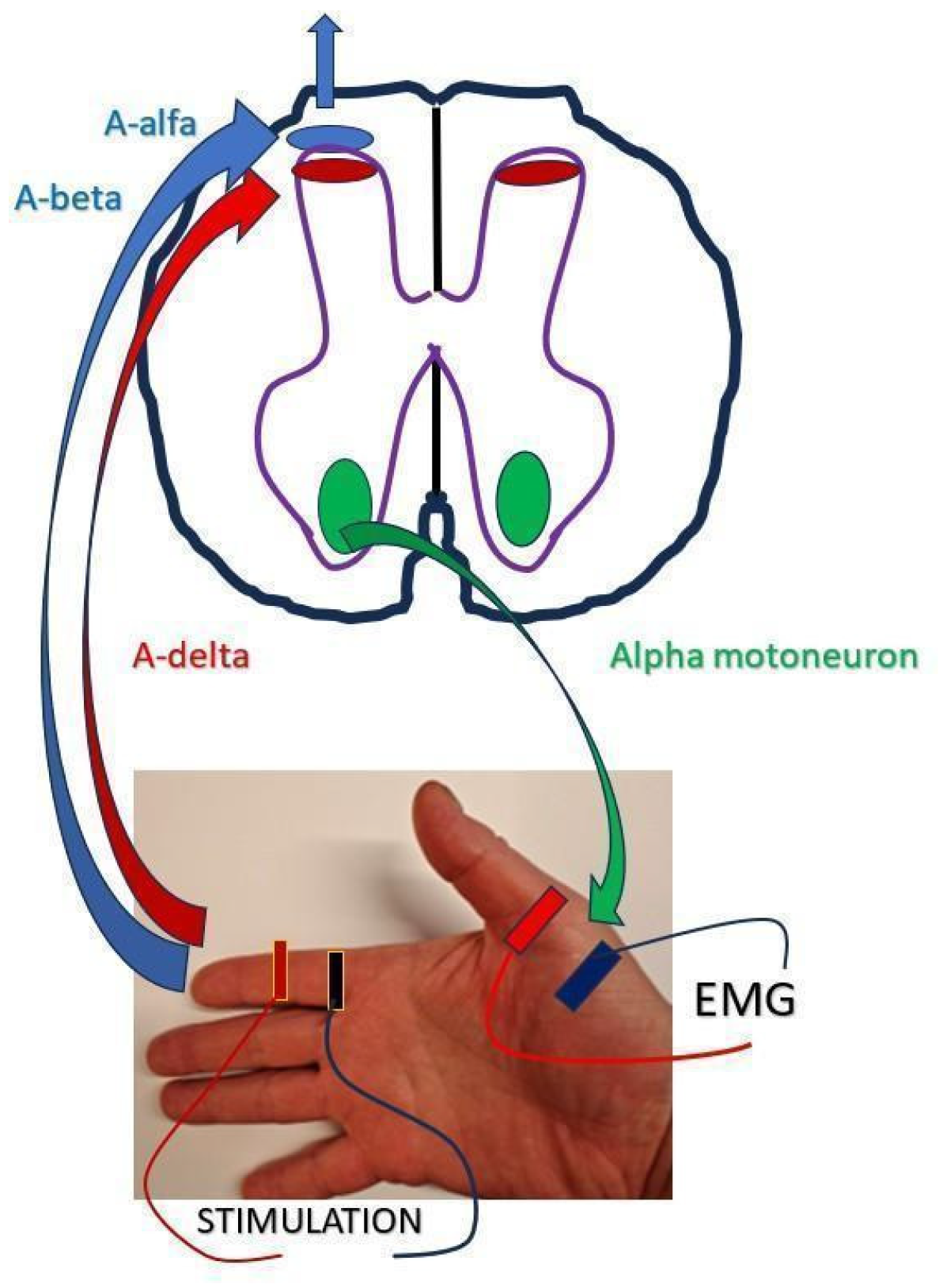

- Stimulating electrode (ref. nr 9013L0362), manufactured by Natus Manufacturing Ltd., Galway, Ireland;

- Recording electrode (ref. nr 9013S0242), manufactured by Ambu A/S, Ballerup, Denmark;

- Grounding electrode (ref. nr GDRGP0450326), manufactured by Spes Medica S.r.l., Genova, Italy.

4.3.1. F-Wave and M-Wave Testing Protocol

4.3.2. CSP Testing Protocol

4.4. Data Collection and Management

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD | cervical dystonia |

| CSP | cutaneous silent period |

| BoNT-A | botulinum toxin type A |

| TCap | torticaput |

| LCap | laterocaput |

| ACap | anterocaput |

| RCap | retrocaput |

| EMG | electromyography |

| APB | abductor pollicis brevis |

References

- Albanese, A.; Bhatia, K.; Bressman, S.B.; DeLong, M.R.; Fahn, S.; Fung, V.S.C.; Fracp, M.H.; Jankovic, J.; Jinnah, H.A.; Klein, C.; et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: A consensus update. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drużdż, A. Current classification of cervical dystonia. In Colour Atlas, 1st ed.; Jost, W., Tatu, L., Eds.; Poznan University of Physical Education: Poznań, Poland, 2022; pp. 8–13. ISBN 978-83-64747-35-9. [Google Scholar]

- Quartarone, A.; Hallett, M. Emerging concepts in the physiological basis of dystonia. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesrati, F.; Vecchierini, M.F. F-waves: Neurophysiology and clinical value. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2004, 34, 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, M.A. F-waves—Physiology and clinical uses. Sci. World J. 2007, 7, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Xu, W.; Liao, S.; Liang, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, X. Clinical and physiological significance of F-wave in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 571341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayşegül, G.; Şenay, A.; Meral, E.K. Cutaneous Silent Period—A literature review. Neurol. Sci. Neurophysiol. 2020, 37, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinazzi, M.; Priori, A.; Bertolasi, L.; Frasson, E.; Mauguière, F.; Fiaschi, A. Abnormal central integration of a dual somatosensory input in dystonia: Evidence from the cutaneous silent period. Brain 2000, 123, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sławek, J.; Bogucki, A.; Bonikowski, M.; Car, H.; Dec-Ćwiek, M.; Drużdż, A.; Koziorowski, D.; Sarzyńska-Długosz, I.; Rudzińska, M. Botulinum toxin type-A preparations are not the same medications—Clinical studies (Part 2). Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2021, 55, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.; Abbruzzese, G.; Dressler, D.; Duzynski, W.; Khatkova, S.; Marti, M.J.; Mir, P.; Montecucco, C.; Moro, E.; Pinter, M.; et al. Practical guidance for CD management involving treatment of botulinum toxin: A consensus statement. J. Neurol. 2015, 262, 2201–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sławek, J.; Bogucki, A.; Budrewicz, S.; Dec-Ćwiek, M.; Drużdż, A.; Koziorowski, D.; Łusakowska, A.; Ochudło, S.; Potulska-Chromik, A.; Rudzińska-Bar, M.; et al. Toksyna botulinowa w leczeniu dystonii oraz połowiczego kurczu twarzy—Rekomendacje Sekcji Schorzeń Pozapiramidowych Polskiego Towarzystwa Neurologicznego oraz Polskiego Towarzystwa Choroby Parkinsona i Innych Zaburzeń Ruchowych. Pol. Prz. Neurol. 2020, 16, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, A.; Defazio, G.; Mascia, M.; Belvisi, D.; Patrizia Pantano, P.; Berardelli, A. Advances in the pathophysiology of adult-onset focal dystonias: Recent neurophysiological and neuroimaging evidence. F1000Research 2020, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlfarth, K.; Schubert, M.; Rothe, B.; Elek, J.; Dengler, R. Remote F-wave changes after local botulinum toxin application. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2001, 112, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chroni, E.; Tendero, I.S.; Punga, A.R. Usefulness of assessing repeater F-waves in routine studies. Muscle Nerve 2003, 45, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kofler, M.; Leis, A.A.; Valls-Solé, J. Cutaneous silent periods—Part 1: Update on physiological mechanisms. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019, 130, 588–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floeter, M.K. Cutaneous silent periods. Muscle Nerve 2003, 28, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.; Bhatia, K.P.; Cardoso, F.; Comella, C.; Defazio, G.; Fung, V.S.; Hallett, M.; Jankovic, J.; Jinnah, H.A.; Kaji, R.; et al. Isolated cervical dystonia: Diagnosis and classification. Mov. Disord. 2023, 38, 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, D.C.; Shapiro, B.E. Electromyography and Neuromuscular Disorders: Clinical–Electrophysiologic–Ultrasound Correlations, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; p. 323. ISBN 978-0-323-66180-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kanovský, P.; Streitová, H.; Dufek, J.; Znojil, V.; Daniel, P.; Rektor, I. Change in lateralization of the P22/N30 cortical component of median nerve somatosensory evoked potentials in patients with cervical dystonia after successful treatment with botulinum toxin A. Mov. Disord. 1998, 13, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilio, F.; Currà, A.; Lorenzano, C.; Modugno, N.; Manfredi, M.; Berardelli, A. Effects of botulinum toxin type A on intracortical inhibition in patients with dystonia. Ann. Neurol. 2000, 48, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, W.H.; Tatu, L.; Pandey, S.; Sławek, J.; Drużdż, A.; Biering-Sørensen, B.; Altmann, C.F.; Kreisler, A. Frequency of different subtypes of cervical dystonia: A prospective multicenter study according to Col–Cap concept. J. Neural Transm. 2019, 127, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, W.H.; Tatu, L. Selection of muscles for botulinum toxin injections in cervical dystonia. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2015, 2, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blythe, J.N.J.S.; Matharu, J.; Reuther, W.J.; Brennan, P.A. Innervation of the lower third of the sternocleidomastoid muscle by the ansa cervicalis through the C1 descendens hypoglossal branch: A previously unreported anatomical variant. Br. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 53, 470–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, Y.-M.; Tang, E.-Y.; Yang, X.-D. Trapezius muscle innervation from the spinal accessory nerve and branches of the cervical plexus. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 37, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, P.A.; Alam, P.; Ammar, M. Sternocleidomastoid innervation from an aberrant nerve arising from the hypoglossal nerve: A prospective study of 160 neck dissections. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2017, 39, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henson, B.; Kadiyala, B.; Edens, M.A. Anatomy, Back, Muscles. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537074/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Graefe, S.B.; Jozsa, F. Neuroanatomy, Suboccipital Nerve. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556133/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Kwon, H.J.; Yang, H.M.; Won, S.Y. Intramuscular innervation patterns of the splenius capitis and splenius cervicis and their clinical implications for botulinum toxin injections. Clin. Anat. 2020, 33, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, J.P.; Munakomi, S. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Levator Scapulae Muscles. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553120/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Cowan, P.T.; Mudreac, A.; Varacallo, M. Anatomy, Back, Scapula. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537228/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Muir, B. Dorsal scapular nerve neuropathy: A narrative review of the literature. J. Can. Chiropr. Assoc. 2017, 61, 128–144. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, M.A.; Hoffor, B.; Hultimol, C. Normative F wave values and the number of recorded F waves. Muscle Nerve 1994, 17, 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puksa, L.; Stalberg, E.; Falck, B. Reference values of F wave parameters in healthy subjects. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003, 114, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiric-Campara, M.; Denislic, M.M.; Djelilovic-Vranic, J.; Alajbegovic, A.; Tupkovic, E.; Gojak, R.; Zorec, R. Cutaneous silent period in the evaluation of small nerve fibres. Med. Arch. 2014, 68, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bölük, C.; Akıncı, Y.; Seyahi, A.; Adatepe, N.U.; Gündüz, A. Sympathetic skin response, cutaneous silent period and nociceptive flexion reflex in Fabry disease. Neurol. Asia 2022, 27, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, E.A.; Silva, J.R. Recording cutaneous silent period parameters in hereditary and acquired neuropathies. Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2022, 80, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofler, M.; Leis, A.; Valls-Solé, J. Cutaneous silent periods—Part 2: Update on pathophysiology and clinical utility. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019, 130, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Waning BoNT-A Mean ± SD Median (Q1–Q3) | Peak BoNT-A Mean ± SD Median (Q1–Q3) | p-Value | d-Cohen | p H–B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fmin (ms) | 23.70 ± 1.90 23.60 (22.05–25.15) | 24.25 ± 1.88 25.00 (22.60–25.13) | 0.026 a | 1.327 | 0.240 |

| Fmax (ms) | 29.22 ± 2.39 29.30 (27.38–31.20) | 29.76 ± 2.67 30.00 (27.70–32.15) | 0.273 a | 0.562 | 0.546 |

| Fmean (ms) | 26.48 ± 1.82 26.90 (24.93–28.00) | 26.78 ± 1.95 27.35 (24.93–27.73) | 0.169 a | 0.885 | 0.676 |

| Chronodisp (ms) | 5.57 ± 1.15 5.40 (4.88–6.10) | 5.05 ± 0.80 4.90 (4.50–5.20) | 0.073 b | 0.849 | 0.438 |

| Fduration (ms) | 12.33 ± 1.76 12.30 (11.00–13.25) | 12.98 ± 2.18 13.10 (11.85–14.45) | 0.235 a | 0.333 | 0.705 |

| Fpersistence (n) | 16.43 ± 2.87 17.00 (13.75–18.25) | 15.52 ± 2.52 16.00 (13.75–17.25) | 0.024 b | 1.128 | 0.240 |

| Fampl (mV) | 0.33 ± 0.07 0.35 (0.30–0.37) | 0.27 ± 0.10 0.27 (0.21–0.35) | 0.040 a | 0.483 | 0.320 |

| Mlat (ms) | 3.70 ± 0.43 3.80 (3.38–4.04) | 3.66 ± 0.46 3.78 (3.34–3.96) | 0.383 a | 0.581 | 0.546 |

| Mampl (mV) | 7.33 ± 1.86 7.50 (6.10–8.43) | 6.91 ± 1.90 6.90 (5.53–8.15) | 0.088 a | 0.979 | 0.440 |

| Marea (ms × mV) | 20.11 ± 6.03 18.10 (17.03–22.73) | 18.60 ± 6.00 17.10 (14.25–23.10) | 0.041 a | 1.280 | 0.320 |

| Parameter | Waning BoNT-A Mean ± SD Median (Q1–Q3) | Peak BoNT-A Mean ± SD Median (Q1–Q3) | p-Value | d-Cohen | p H–B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F/Mampl (ratio) | 4.91 ± 2.04 4.53 (3.85–5.25) | 4.31 ± 2.16 3.98 (2.79–5.39) | 0.099 b | 0.772 | 0.198 |

| F/Mlat (ratio) | 34.67 ± 5.04 33.49 (32.05–38.05) | 35.75 ± 5.19 35.59 (32.13–40.03) | 0.730 a | 0.465 | 0.730 |

| F–Mlat (ms) | 20.00 ± 1.90 20.10 (18.60–21.21) | 20.59 ± 1.93 20.80 (19.22–21.83) | 0.022 a | 1.335 | 0.110 |

| CV1 (m/s) | 78.83 ± 6.64 79.39 (72.29–81.31) | 76.45 ± 6.70 77.65 (72.09–81.17) | 0.022 a | 1.160 | 0.110 |

| CV2 (m/s) | 83.11 ± 6.87 83.62 (76.22–85.99) | 80.60 ± 6.94 81.26 (76.07–85.63) | 0.022 a | 1.160 | 0.110 |

| Parameter | Waning BoNT-A Mean ± SD Median (Q1–Q3) | Peak BoNT-A Mean ± SD Median (Q1–Q3) | p-Value | d-Cohen | p H–B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSPo (ms) | 77.69 ± 12.62 72.40 (67.13–88.38) | 78.15 ± 11.80 74.00 (68.90–89.25) | 0.482 a | 0.949 | 0.482 |

| CSPe (ms) | 116.32 ± 10.54 115.00 (107.88–123.73) | 126.84 ± 7.80 128.00 (118.98–133.25) | <0.0001 a | 3.953 | 0.00036 |

| CSPd (ms) | 38.64 ± 5.89 39.20 (33.63–42.93) | 48.69 ± 7.33 48.40 (43.23–51.95) | <0.0001 a | 3.932 | 0.00036 |

| CSPom (ms) | 65.40 ± 12.93 62.00 (54.95–72.48) | 68.16 ± 11.27 67.00 (60.13–73.30) | 0.009 a | 2.703 | 0.018 |

| Parameter | Waning BoNT-A Mean ± SD Median (Q1–Q3) | Peak BoNT-A Mean ± SD Median (Q1–Q3) | p-Value | d-Cohen | p H-B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV3—Sensory CV (m/s) | 9.86 ± 1.88 10.50 (8.16–11.26) | 9.77 ± 1.77 10.24 (8.49–11.18) | 0.244 a | 2.110 | 0.244 |

| CV4—Motor CV (m/s) | 21.88 ± 4.00 21.64 (18.68–24.23) | 17.26 ± 2.57 16.86 (15.48–19.66) | <0.0001 a | 3.913 | 0.00036 |

| CV5—Total CV (m/s) | 14.86 ± 1.99 15.04 (13.61–16.10) | 13.55 ± 1.41 13.48 (12.93–14.32) | <0.0001 a | 4.913 | 0.00036 |

| Pattern | Injection Side | Muscle | Innervation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Torticaput | Contralateral | Trapezius pars descendens (P) Sternocleidomastoideus (P) Semispinalis capitis pars med (S) | CN XI, cervical plexus [23,24,25] CN XI, cervical plexus [23,24,25] Dorsal rami of C1–C5 [26] |

| Ipsilateral | Obliquus capitis inferior (P) Splenius capitis (S) | Suboccipital nerve (dorsal ramus of C1) [27] Dorsal rami of C2–C3 [26,28] | |

| Laterocaput | Ipsilateral | Sternocleidomastoideus (P) Trapezius pars descendens (P) Splenius capitis (P) Semispinalis capitis (S) Levator scapulae (S) | CN XI, cervical plexus [23,24,25] CN XI, cervical plexus [23,24,25] Dorsal rami of C2–C3 [26,28] Dorsal rami of C1–C5 [26] Dorsal scapular nerve (C5), C3–C4 cervical nerves [29,30,31] |

| Anterocaput | Bilateral | Levator scapulae (P) Sternocleidomastoideus (S) | Dorsal scapular nerve (C5), C3–C4 cervical nerves [28,29,30] CN XI, cervical plexus [22,23,24] |

| Retrocaput | Bilateral | Obliquus capitis inferior (P) Semispinalis capitis (P) Trapezius pars descendens (P) Splenius capitis (S) | Suboccipital nerve (dorsal ramus of C1) [27] Dorsal rami of C1–C5 [25] CN XI, cervical plexus [22,23,24] Dorsal rami of C2–C3 [26,28] |

| Parameter Abbrev. | Parameter Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

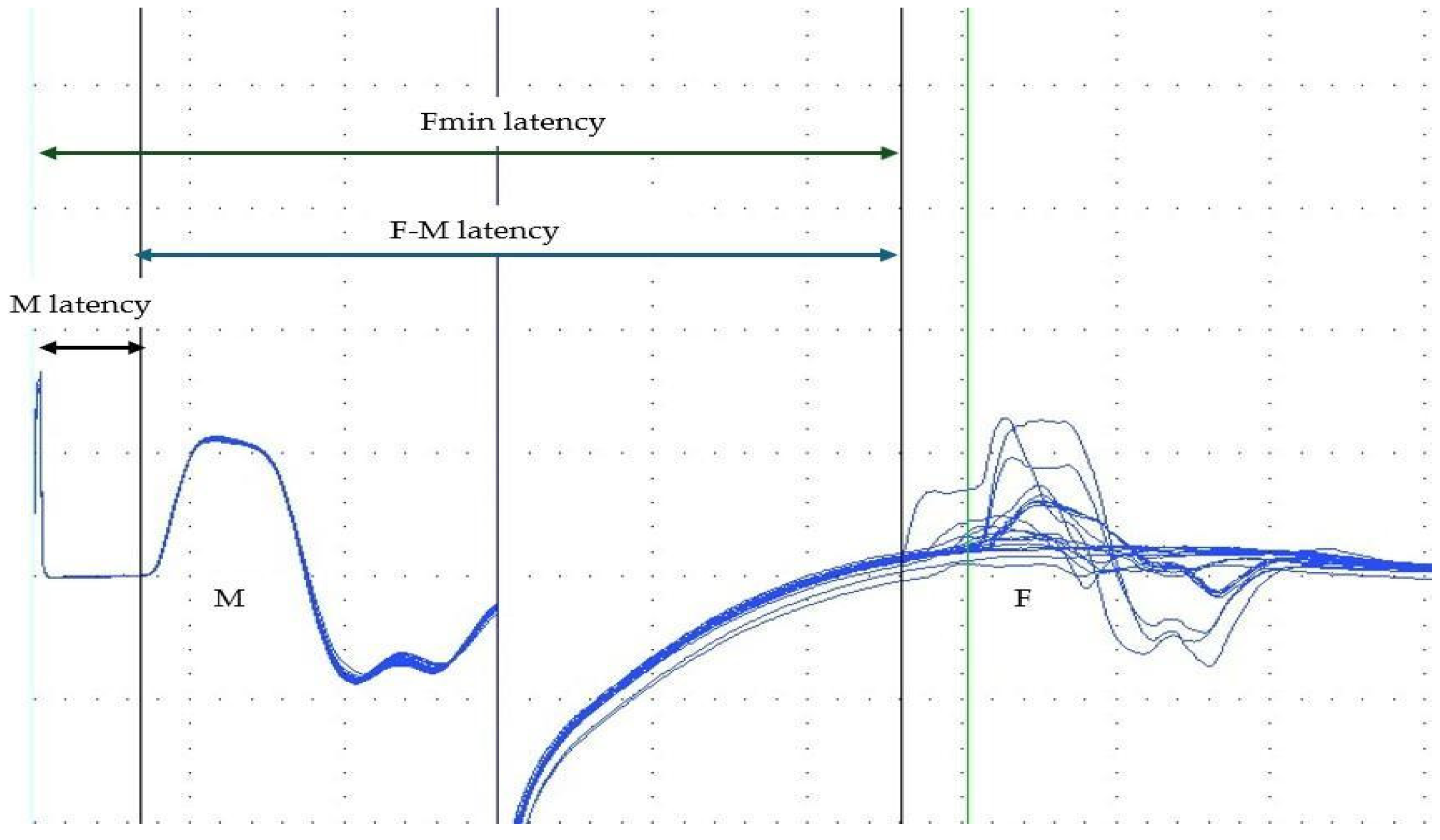

| Fmin | Minimal latency of all F-wave responses received | ms |

| Fmax | Maximal latency of all F-wave responses received | ms |

| Fmean | Calculated as Fmin + (Fmax − Fmin)/2 | ms |

| Fchronodisp | Chronodispersion of F-waves; interval between Fmin and Fmax | ms |

| Fduration | Mean duration of each F-wave response | ms |

| Fpersistence | Number of F-wave responses observed in 20 stimulations | - |

| Fampl | Mean amplitude of all F-wave responses | mV |

| Mlat | Latency of M-wave | ms |

| Mampl | Maximal amplitude of M-wave | mV |

| Marea | Area under the curve of M-wave | ms × mV |

| Distance Abbrev. | Distance description | Unit |

| D1 | Double the distance from the stimulating electrode on the wrist along the forearm and upper arm, the axilla, the Erb’s point, to the spinous process of C7. | cm |

| D2 | D1 plus the distance from the stimulating cathode on the wrist to the recording electrode in the middle of the abductor pollicis brevis (APB) muscle. | cm |

| Abbrev. | Description | Formula | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| F/Mampl | F/M amplitude ratio | Mean F-wave amplitude ÷ Maximal M-wave | - |

| F/Mlat | F/M latency ratio | ((Fmin − Mlat − 1)/2) × Mlat | - |

| F–Mlat | F–M latency difference | Fmin − Mlat | ms |

| CV1 | Conduction velocity 1 (along the motor pathways) | D1 ÷ Fmin latency | m/s |

| CV2 | Conduction velocity 2 (along the motor pathways) | D2 ÷ Fmin latency | m/s |

| Parameter Abbrev. | Parameter Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| CSPo | Latency at the beginning of muscle activity suppression | ms |

| CSPe | Latency at the onset of renewed muscle activity | ms |

| CSPd | Duration of the silent period, Calculated as CSPe − CSPo | ms |

| CSPom | Onset minimal latency of voluntary suppression across eight responses | ms |

| Distance Abbrev. | Distance description | Unit |

| D3 | Distance from the stimulating electrode on the right index finger to the centre of the wrist, along the forearm and the upper arm to the axilla, the Erb’s point, to the spinous process of C7 | cm |

| D4 | Distance from the recording electrode in the middle of the right abductor pollicis brevis (APB) muscle, to the centre of the wrist, along the forearm and the upper arm to the axilla, the Erb’s point, to the spinous process of C7 | cm |

| D5 | Sum of D3 and D4 | cm |

| Abbrev. | Description | Formula | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| CV3 | Sensory conduction velocity | D3 ÷ CSPo | m/s |

| CV4 | Motor (conduction) velocity (motor pathway) | D4 ÷ CSP duration | m/s |

| CV5 | Total conduction velocity (motorsensory circuit) | D5 ÷ CSPe | m/s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Drużdż, A.; Leśniewska-Furs, E.; Dudzic, M.; Sowińska, A.; Jurga, S.; Jost, W.H. Neurophysiological Assessment of F-Wave, M-Wave, and Cutaneous Silent Period in Patients with Caput-Pattern Cervical Dystonia at Waning and Peak Response Phases of Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Toxins 2026, 18, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010021

Drużdż A, Leśniewska-Furs E, Dudzic M, Sowińska A, Jurga S, Jost WH. Neurophysiological Assessment of F-Wave, M-Wave, and Cutaneous Silent Period in Patients with Caput-Pattern Cervical Dystonia at Waning and Peak Response Phases of Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Toxins. 2026; 18(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrużdż, Artur, Edyta Leśniewska-Furs, Małgorzata Dudzic, Anna Sowińska, Szymon Jurga, and Wolfgang H. Jost. 2026. "Neurophysiological Assessment of F-Wave, M-Wave, and Cutaneous Silent Period in Patients with Caput-Pattern Cervical Dystonia at Waning and Peak Response Phases of Botulinum Toxin Therapy" Toxins 18, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010021

APA StyleDrużdż, A., Leśniewska-Furs, E., Dudzic, M., Sowińska, A., Jurga, S., & Jost, W. H. (2026). Neurophysiological Assessment of F-Wave, M-Wave, and Cutaneous Silent Period in Patients with Caput-Pattern Cervical Dystonia at Waning and Peak Response Phases of Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Toxins, 18(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins18010021