Study on the Dynamic Changes in Fungal Communities During the Storage of Polygalae Radix and the Antifungal Effects of Peppermint Essential Oil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Fungal Community Changes During the Storage of Polygalae Radix Samples

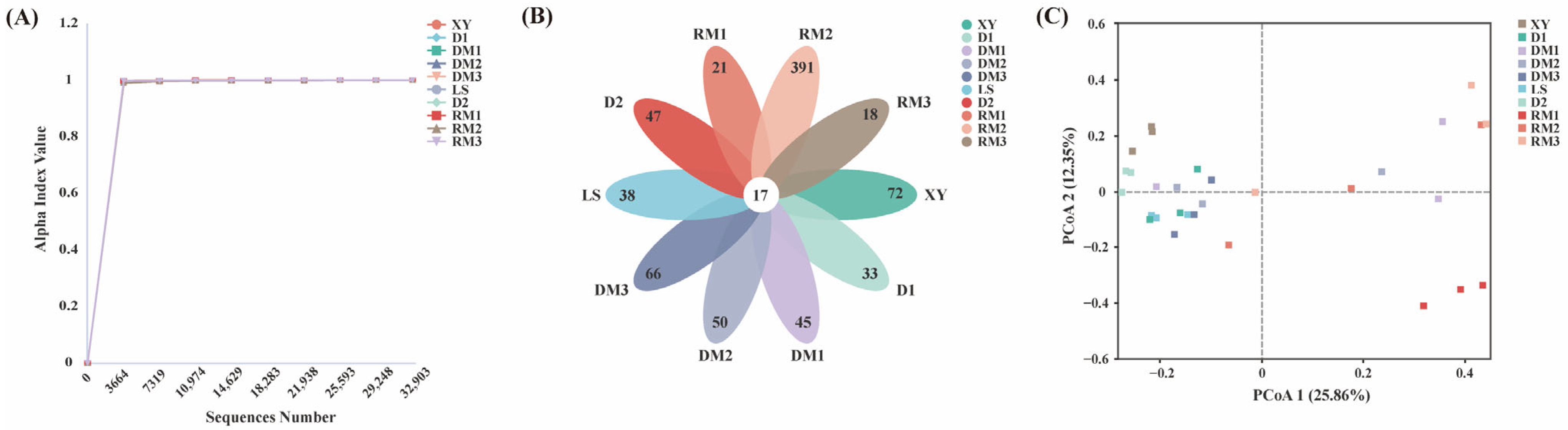

2.1.1. Diversity of Fungal Communities in Polygalae Radix Samples

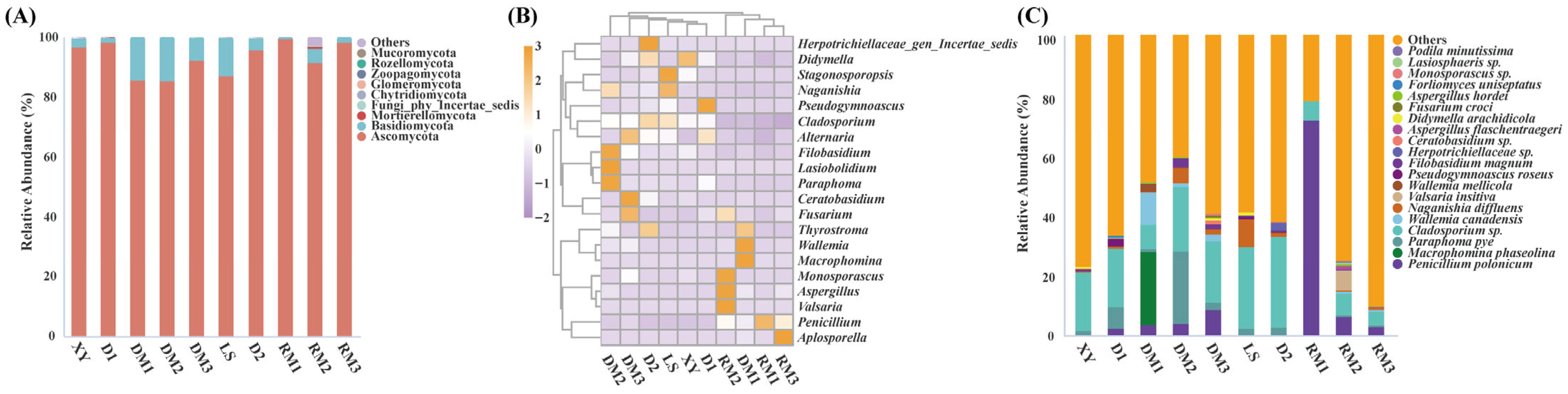

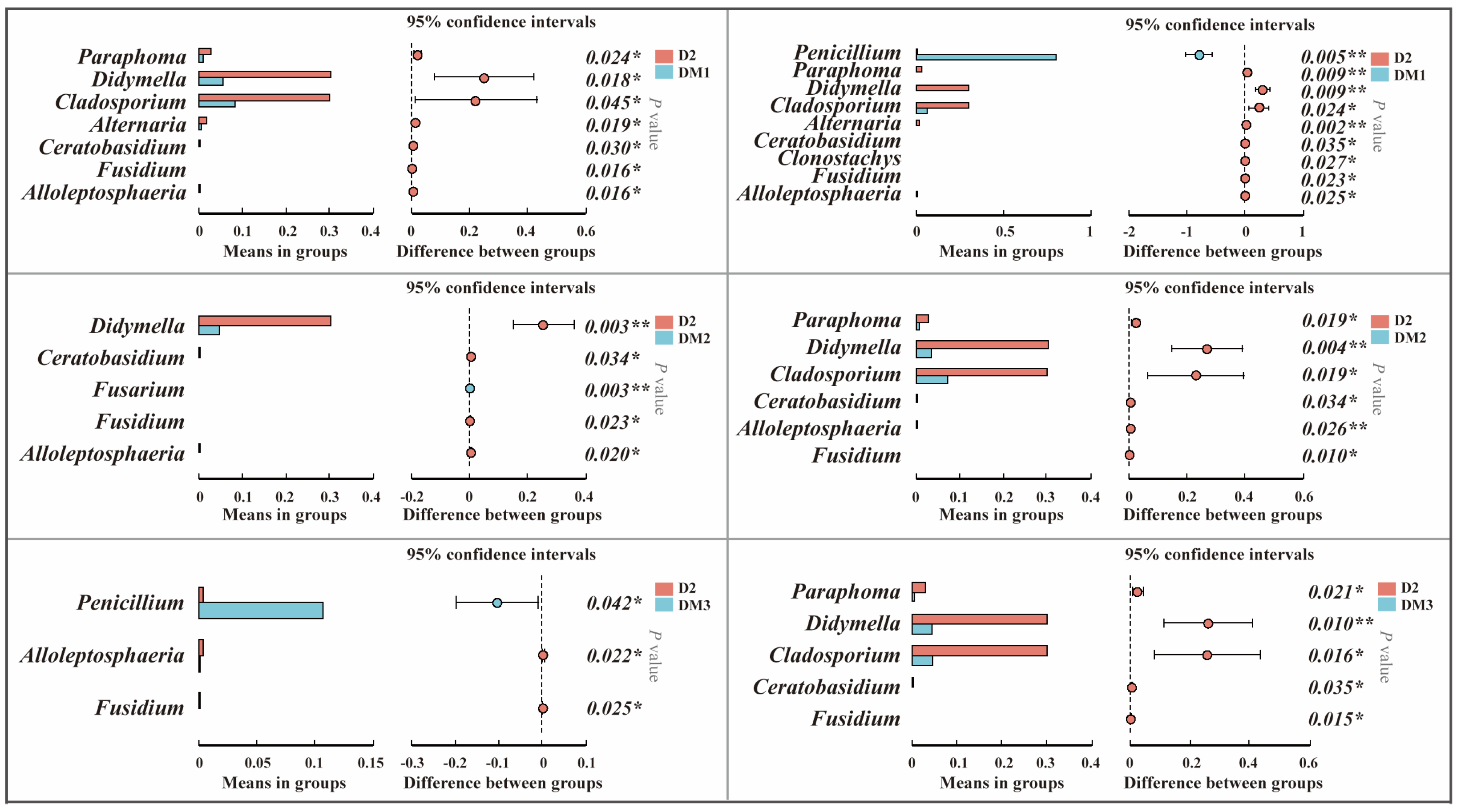

2.1.2. Composition of Fungal Communities in Polygalae Radix Samples

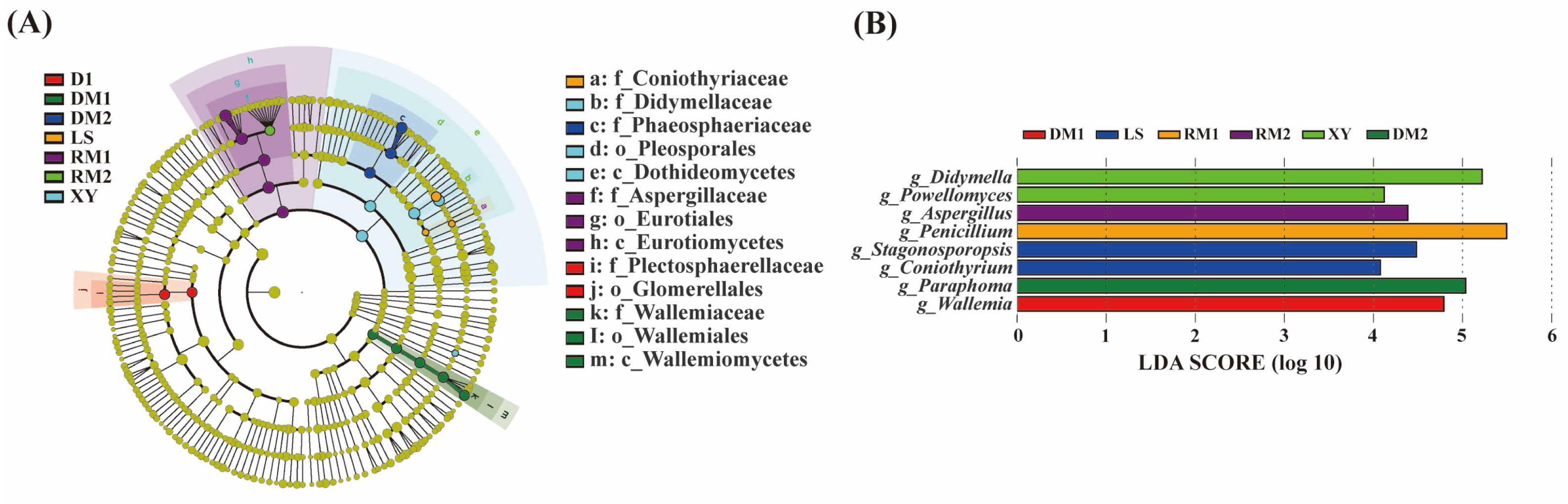

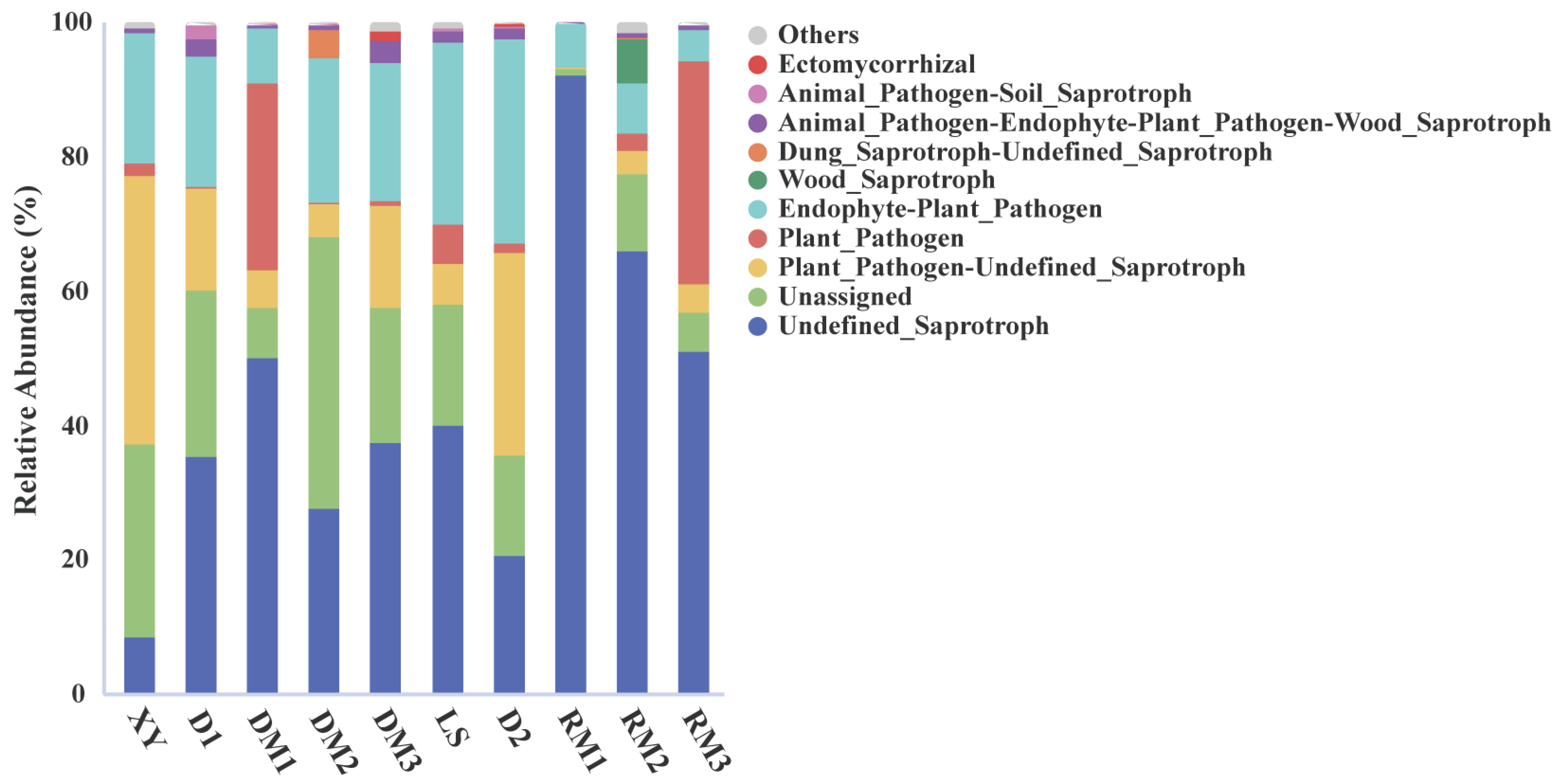

2.1.3. Functional Prediction

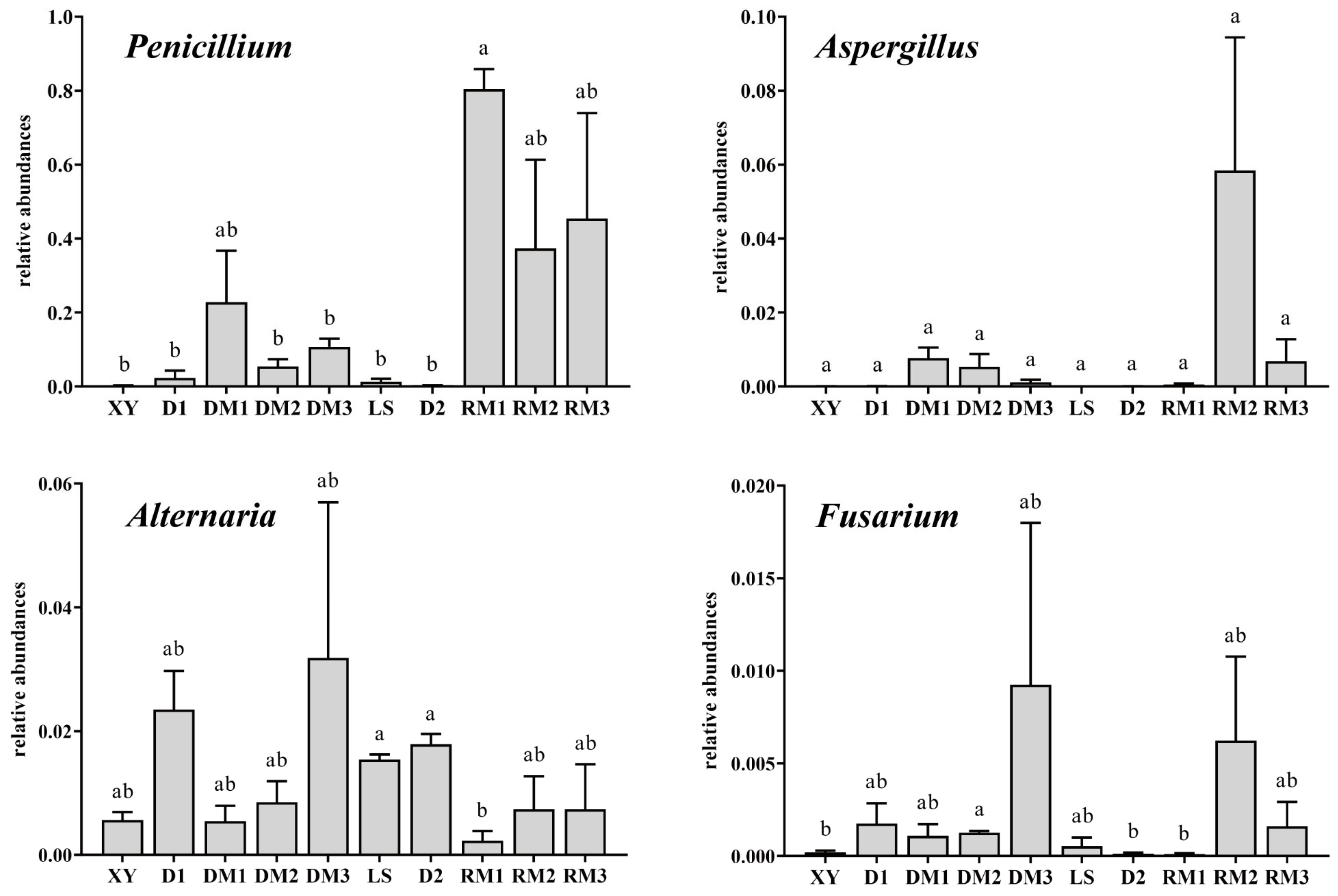

2.1.4. Analysis of Mycotoxigenic Fungi of All Samples

2.2. Antifungal Effects of PEO Against A. flavus in Stored Polygalae Radix

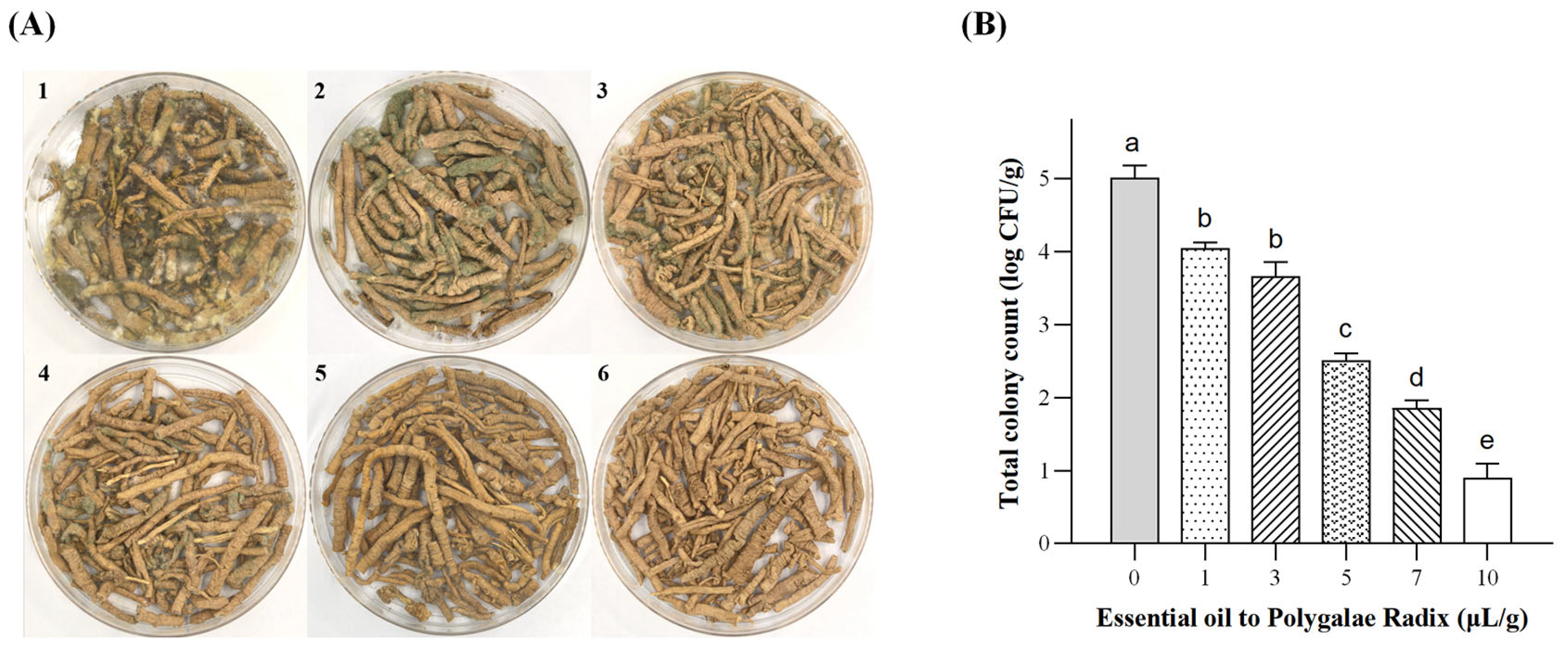

2.2.1. Growth Status and Enumeration of A. flavus in Polygalae Radix

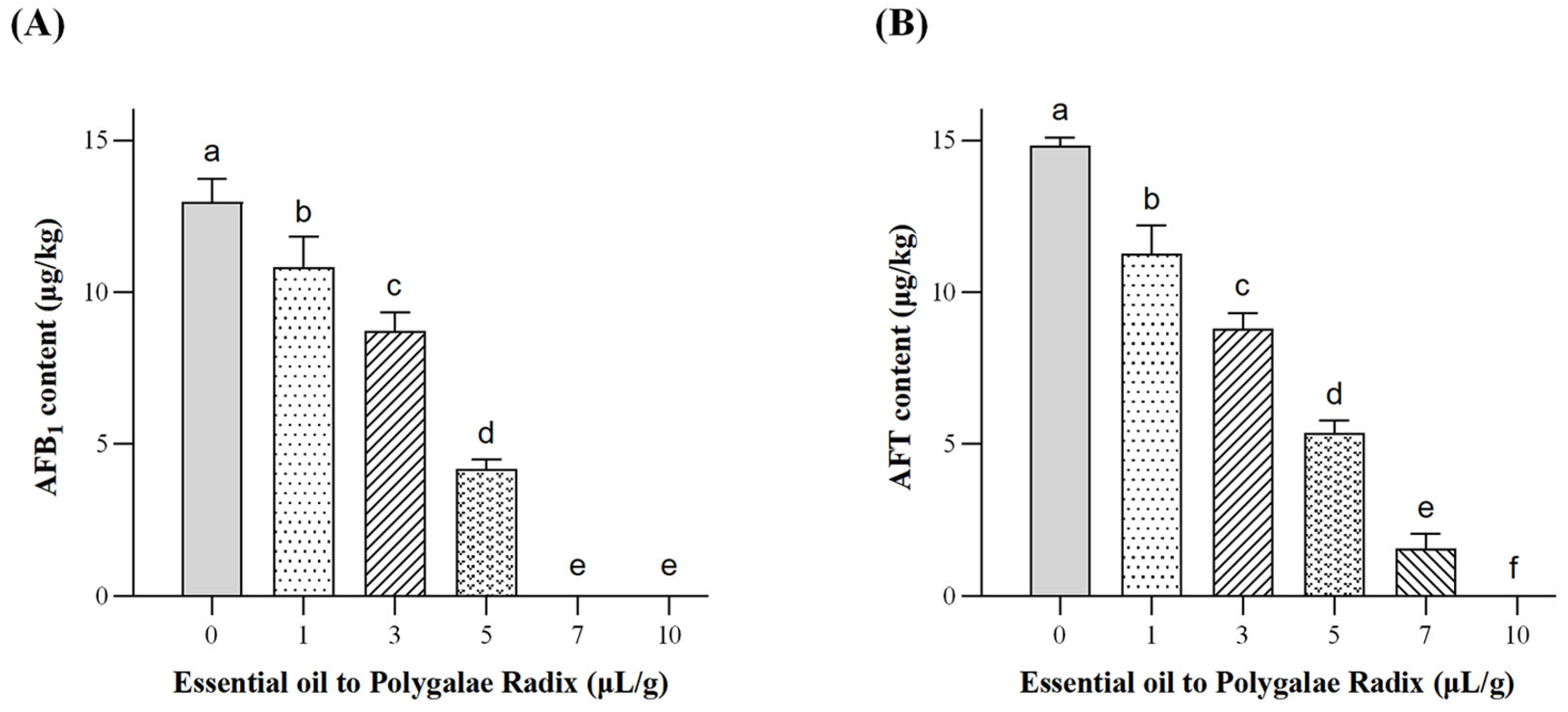

2.2.2. Determination of Aflatoxin Content in Polygalae Radix by IAC-HPLC-FLD

3. Discussion

3.1. Changes in Fungal Communities During the Storage of Polygalae Radix

3.2. Inhibitory Effects of PEO on A. flavus and Its Potential Application in the Storage of Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicines

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Materials

5.2. Methods

5.2.1. Fungal Community Dynamics During Polygalae Radix Storage

DNA Extraction and Sequencing

Bioinformatics Analysis

5.2.2. Evaluation of the Optimal Concentration of PEO Against A. flavus in Stored Polygalae Radix

Preparation of A. flavus Spore Suspension

Inoculation of Polygalae Radix with A. flavus Spores

Vapor-Phase Fumigation with PEO

Assessment of A. flavus Growth

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, L.; Yong, Y.-Y.; Deng, L.; Wang, J.; Law, B.Y.-K.; Hu, M.-L.; Wu, J.-M.; Yu, L.; Wong, V.K.-W.; Yu, C.-L.; et al. Therapeutic Potential of Polygala Saponins in Neurological Diseases. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2023, 108, 154483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Hu, Y.; Gao, D.; Luo, Y.; Chen, A.J.; Jiao, X.; Gao, W. Occurrence of Toxigenic Fungi and Mycotoxins on Root Herbs from Chinese Markets. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngindu, A.; Johnson, B.K.; Kenya, P.R.; Ngira, J.A.; Ocheng, D.M.; Nandwa, H.; Omondi, T.N.; Jansen, A.J.; Ngare, W.; Kaviti, J.N.; et al. Outbreak of Acute Hepatitis Caused by Aflatoxin Poisoning in Kenya. Lancet Lond. Engl. 1982, 1, 1346–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benkerroum, N. Aflatoxins: Producing-Molds, Structure, Health Issues and Incidence in Southeast Asian and Sub-Saharan African Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedayati, M.T.; Pasqualotto, A.C.; Warn, P.A.; Bowyer, P.; Denning, D.W. Aspergillus flavus: Human Pathogen, Allergen and Mycotoxin Producer. Microbiol. Read. Engl. 2007, 153 Pt 6, 1677–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostry, V.; Malir, F.; Toman, J.; Grosse, Y. Mycotoxins as Human Carcinogens-the IARC Monographs Classification. Mycotoxin Res. 2017, 33, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China: 2020 Edition; China Medical Science Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Tao, M.; Chen, X.; Li, Q. On Quality Problems of Polygalae Radix and Primary Processing of Traditional Chinese Medicinal Materials. Chin. Pharm. Aff. 2018, 32, 1467–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Derbal, S. Microbial Contamination of Medicinal Plants. J. Mol. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 2, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.; Wu, Q.-H.; Liu, Y.-P.; Tang, X.-M.; Ren, C.-X.; Chen, J.; Pei, J. Microbial community diversity and its characteristics in Magnolia officinalis Cortex “sweating” process based on high-throughput sequencing. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2019, 44, 5405–5412. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Chen, S.; Dong, L. Sampling Locations and Processing Methods Shape Fungi Microbiome on the Surface of Edible and Medicinal Arecae Semen. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1188986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Jiang, W.; Yang, M.; Dou, X.; Pang, X. Characterizing Fungal Communities in Medicinal and Edible Cassiae Semen Using High-Throughput Sequencing. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 319, 108496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Pandey, A.K. Prospective of Essential Oils of the Genus Mentha as Biopesticides: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plavsic, D.; Skrinjar, M.; Psodorov, D.; Pezo, L.; Milovanovic, I.; Psodorov, D.; Kojic, P.; Kocic-Tanackov, S. Chemical Structure Components and Antifungal Activity of Mint Essential Oil. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2020, 85, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, A.; Dehestani-Ardakani, M.; Meftahizadeh, H.; Gholamnezhad, J.; Hatami, M. Edible Coatings Based on Guar Gum and Peppermint Essential Oil Alter the Quality Enhancement of Zagh Pomegranate Arils during the Postharvest Supply Chain. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2023, 15, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayon Reyna, L.E.; Uriarte Gastelum, Y.G.; Camacho Diaz, B.H.; Tapia Maruri, D.; Lopez Lopez, M.E.; Lopez Velazquez, J.G.; Vega Garcia, M.O. Antifungal Activity of a Chitosan and Mint Essential Oil Coating on the Development of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides in Papaya Using Macroscopic and Microscopic Analysis. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 15, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Vázquez, M.A.K.; Pacheco-Hernández, Y.; Lozoya-Gloria, E.; Mosso-González, C.; Ramírez-García, S.A.; Romero-Arenas, O.; Villa-Ruano, N. Peppermint Essential Oil and Its Major Volatiles as Protective Agents against Soft Rot Caused by Fusarium sambucinum in Cera Pepper (Capsicum pubescens). Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Bao, Z.; Hao, J.; Ma, X.; Jia, C.; Liu, M.; Wei, D.; Yang, S.; Qin, J. A Novel Preservative Film with a Pleated Surface Structure and Dual Bioactivity Properties for Application in Strawberry Preservation Due to Its Efficient Apoptosis of Pathogenic Fungal Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 18027–18044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Kamal, M.; Altaie, H.A.A.; Youssef, I.M.; Algarni, E.H.; Almohmadi, N.H.; Abukhalil, M.H.; Khafaga, A.F.; Alqhtani, A.H.; Swelum, A.A. Peppermint Essential Oil and Its Nano-emulsion: Potential Against Aflatoxigenic Fungus Aspergillus flavus in Food and Feed. Toxicon 2023, 234, 107309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abo Hager, A.A.; EI Moghazy, G.M.; Atwa, M.A.; Elgammal, M.H. Studies on the Effects of Some Medicinal Plants Essential Oils on the Growth and Aflatoxins Synthesis of Aspergillus flavus. J. Agric. Chem. Biotechn. 2014, 5, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujur, A.; Kumar, A.; Yadav, A.; Prakash, B. Antifungal and Aflatoxin B1 Inhibitory Efficacy of Nanoencapsulated Pelargonium graveolens L. Essential Oil and Its Mode of Action. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 130, 109619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sao, J.; Polona, Z.; Dragi, K.; Hans-Josef, S.; Saso, D.; Nina, G.-C. Halophily Reloaded: New Insights into the Extremophilic Life-Style of Wallemia with the Description of Wallemia hederae sp. nov. Fungal Divers. 2016, 76, 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Jančič, S.; Frisvad, J.C.; Kocev, D.; Gostinčar, C.; Džeroski, S.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. Production of Secondary Metabolites in Extreme Environments: Food- and Airborne Wallemia spp. Produce Toxic Metabolites at Hypersaline Conditions. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0169116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botić, T.; Kunčič, M.K.; Sepčić, K.; Knez, Z.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. Salt Induces Biosynthesis of Hemolytically Active Compounds in the Xerotolerant Food-Borne Fungus Wallemia sebi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012, 326, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desroches, T.C.; McMullin, D.R.; Miller, J.D. Extrolites of Wallemia sebi, a Very Common Fungus in the Built Environment. Indoor Air 2014, 24, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, B.; Ashiq, S.; Hussain, A.; Bashir, S.; Hussain, M. Evaluation of Mycotoxins, Mycobiota, and Toxigenic Fungi in Selected Medicinal Plants of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Fungal Biol. 2014, 118, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Xu, H.; Wang, W.; Zhan, R.; Chen, W. Simultaneous Determination of Aflatoxin B1, B2, G1, G2, Ochratoxin A, and Sterigmatocystin in Traditional Chinese Medicines by LC-MS-MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 3031–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.J.; Jiao, X.; Hu, Y.; Lu, X.; Gao, W. Mycobiota and Mycotoxins in Traditional Medicinal Seeds from China. Toxins 2015, 7, 3858–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.J.; Huang, L.F.; Wang, L.Z.; Tang, D.; Cai, F.; Gao, W.W. Occurrence of Toxigenic Fungi in Ochratoxin A Contaminated Liquorice Root. Food Addit. Contam. Part Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2011, 28, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, S.; Piombo, E.; Schroeckh, V.; Meloni, G.R.; Heinekamp, T.; Brakhage, A.A.; Spadaro, D. CRISPR-Cas9-Based Discovery of the Verrucosidin Biosynthesis Gene Cluster in Penicillium polonicum. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 660871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, X.; Jiang, D.; Wang, J.; Li, T.; Ren, G.; Mi, J.; Jin, M.; Hua, G.; Liu, C. Aflatoxins and Changes of Aspergillus flavus on Polygalae Radix during Storage. Mod. Chin. Med. 2021, 23, 1921–1926. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lei, Z.; Gao, W. Investigation of Aflatoxins and Toxigenic Fungi Contamination during Post-Harvest Processing of Polygalae Radix. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2020, 51, 2851–2856. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Zhou, W.; Li, K.; Zhao, M.; Yang, M. Study on Influence of Different Storage Environments and Packaging Materials on Quality of Citri Reticulatae pericarpium. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2018, 43, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yi, Y.; Liu, R.; Shang, Z.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Lou, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, P. Peppermint Essential Oil For Controlling Aspergillus flavus and Analysis of Its Antifungal Action Mode. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Xu, Z.; Deng, R.; Huang, L.; Zheng, R.; Kong, Q. Peppermint essential oil suppresses Geotrichum citri-aurantii growth by destructing the cell structure, internal homeostasis, and cell cycle. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7786–7797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, Z.K.; Abosereh, N.A.; Salim, R.G.; El-Sayed, A.F.; Aly, S.E. Unraveling the Antifungal and Aflatoxin B1 Inhibitory Efficacy of Nano-Encapsulated Caraway Essential Oil Based on Molecular Docking of Major Components. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Chávez, M.M.; Cárdenas-Ortega, N.C.; Méndez-Ramos, C.A.; Pérez-Gutiérrez, S. Fungicidal Properties of the Essential Oil of Hesperozygis Marifolia on Aspergillus flavus Link. Molecules 2011, 16, 2501–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, H. Antifungal Activity of the Volatile Phase of Essential Oils: A Brief Review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2007, 2, 1297–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, Y.B.; Belasli, A.; Djenane, D.; Ariño, A.; Miri, Y.B.; Belasli, A.; Djenane, D.; Ariño, A. Prevention by Essential Oils of the Occurrence and Growth of Aspergillus flavus and Aflatoxin B1 Production in Food Systems: Review. In Aflatoxin B1 Occurrence, Detection and Toxicological Effects; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mani-López, E.; Cortés-Zavaleta, O.; López-Malo, A. A Review of the Methods Used to Determine the Target Site or the Mechanism of Action of Essential Oils and Their Components against Fungi. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chen, M.; Ren, G.; Hua, G.; Mi, J.; Jiang, D.; Liu, C. Antifungal Activity of Essential Oil From Zanthoxylum Armatum DC. on Aspergillus flavus and Aflatoxins in Stored Platycladi Semen. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 633714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camiletti, B.X.; Torrico, A.K.; Maurino, M.F.; Cristos, D.; Magnoli, C.; Lucini, E.I.; Pecci, M.D.L.P.G. Fungal Screening and Aflatoxin Production by Aspergillus Section Flavi Isolated from Pre-Harvest Maize Ears Grown in Two Argentine Regions. Crop Prot. 2017, 92, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Hubka, V.; Ezekiel, C.N.; Diana Di Mavungu, J.; Landschoot, S.; Kyallo, M.; Njuguna, J.; Harvey, J.; De Saeger, S. Taxonomy of Aspergillus Section Flavi and Their Production of Aflatoxins, Ochratoxins and Other Mycotoxins. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 93, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoth, S.; De Boevre, M.; Vidal, A.; Diana Di Mavungu, J.; Landschoot, S.; Kyallo, M.; Njuguna, J.; Harvey, J.; De Saeger, S. Genetic and Toxigenic Variability within Aspergillus flavus Population Isolated from Maize in Two Diverse Environments in Kenya. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldan, N.C.; Almeida, R.T.R.; Avíncola, A.; Porto, C.; Galuch, M.B.; Magon, T.F.S.; Pilau, E.J.; Svidzinski, T.I.E.; Oliveira, C.C. Development of an Analytical Method for Identification of Aspergillus flavus Based on Chemical Markers Using HPLC-MS. Food Chem. 2018, 241, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Cao, P.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Song, J.; Han, J. CuO, ZnO, and γ-Fe2O3 Nanoparticles Modified the Underground Biomass and Rhizosphere Microbial Community of Salvia miltiorrhiza (Bge.) after 165-Day Exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 217, 112232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Wei, X.; Wang, G.; Chen, X.; Han, J.; Li, Y. Microbial Inoculants and Garbage Fermentation Liquid Reduced Root-Knot Nematode Disease and As Uptake in Panax quinquefolium Cultivation by Modulating Rhizosphere Microbiota Community. Chin. Herb. Med. 2022, 14, 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. Preparation and Application of Chinese Herbal Medicines Materials of Natural Plant Mould-Proof Tablet. Bachelor’s Thesis, Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, Harbin, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.-B.; Qin, Y.-L.; Li, S.-F.; Lv, Y.Y.; Zhai, H.C.; Hu, Y.S.; Cai, J.P. Antifungal Mechanism of 1-Nonanol against Aspergillus flavus Growth Revealed by Metabolomic Analyses. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 7871–7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skalicka-Woźniak, K.; Walasek, M. Preparative Separation of Menthol and Pulegone from Peppermint Oil (Mentha piperita L.) by High-Performance Counter-Current Chromatography. Phytochem. Lett. 2014, 10, xciv–xcviii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 4789.15-2016; National Food Safety Standard—Food Microbiological Examination—Enumeration of Molds and Yeasts. National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Wen, J.; Kong, W.; Wang, J.; Yang, M. Simultaneous Determination of Four Aflatoxins and Ochratoxin A in Ginger and Related Products by HPLC with Fluorescence Detection after Immunoaffinity Column Clean-up and Postcolumn Photochemical Derivatization. J. Sep. Sci. 2013, 36, 3709–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.Y.; Luo, L.; Shan, H.; Wang, H.D. Determination of Aflatoxin B1 in Edible Oil by High Performance Liquid Chromatography. Food Saf. Guide 2024, 36, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, K. Analysis of the Capability Verification Results and Critical Control Point for the Determination of Aflatoxin B1 in Vegetable Oil by High Performance Liquid Chromatography. Mod. Food 2024, 30, 190–198. [Google Scholar]

| Sample Name | Good’s Coverage Index | Chao1 Index | Shannon Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| XY | 0.99978 | 95.28 ± 18.84 a | 2.94 ± 0.28 a |

| D1 | 0.99988 | 68.75 ± 12.14 a | 2.87 ± 0.32 a |

| DM1 | 0.99983 | 76.7 ± 15.25 a | 2.58 ± 0.86 a |

| DM2 | 0.99991 | 72.17 ± 14.22 a | 2.99 ± 1.12 a |

| DM3 | 0.99985 | 84.08 ± 46.19 a | 3.15 ± 0.63 a |

| LS | 0.99984 | 75.92 ± 11.16 a | 2.80 ± 0.38 a |

| D2 | 0.99985 | 89.17 ± 13.04 a | 2.91 ± 0.24 a |

| RM1 | 0.99997 | 33.33 ± 4.51 a | 1.47 ± 0.52 a |

| RM2 | 0.99974 | 190.67 ± 203.32 a | 3.52 ± 1.88 a |

| RM3 | 0.99992 | 51.58 ± 42.49 a | 1.49 ± 2.10 a |

| No. | Sample Name | Collection Location | Storage Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | XY | Yulin, Shaanxi | Freshly harvested samples |

| 2 | D1 | Yulin, Shaanxi | Air-dried for 2 days |

| 3 | DM1 | Yulin, Shaanxi | Stored for 1 month |

| 4 | DM2 | Yulin, Shaanxi | Stored for 2 months |

| 5 | DM3 | Yulin, Shaanxi | Stored for 3 months |

| 6 | LS | Yuncheng, Shanxi | Freshly harvested samples |

| 7 | D2 | Yuncheng, Shanxi | Air-dried for 2 days |

| 8 | RM1 | Yuncheng, Shanxi | Stored for 1 month |

| 9 | RM2 | Yuncheng, Shanxi | Stored for 2 months |

| 10 | RM3 | Yuncheng, Shanxi | Stored for 3 months |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Ren, Y.; Li, J.; Han, J. Study on the Dynamic Changes in Fungal Communities During the Storage of Polygalae Radix and the Antifungal Effects of Peppermint Essential Oil. Toxins 2025, 17, 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120585

Zhang H, Su Y, Wang X, Ren Y, Li J, Han J. Study on the Dynamic Changes in Fungal Communities During the Storage of Polygalae Radix and the Antifungal Effects of Peppermint Essential Oil. Toxins. 2025; 17(12):585. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120585

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hui, Yuying Su, Xinnan Wang, Ying Ren, Jinfeng Li, and Jianping Han. 2025. "Study on the Dynamic Changes in Fungal Communities During the Storage of Polygalae Radix and the Antifungal Effects of Peppermint Essential Oil" Toxins 17, no. 12: 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120585

APA StyleZhang, H., Su, Y., Wang, X., Ren, Y., Li, J., & Han, J. (2025). Study on the Dynamic Changes in Fungal Communities During the Storage of Polygalae Radix and the Antifungal Effects of Peppermint Essential Oil. Toxins, 17(12), 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120585