Beta Toxins Isolated from the Scorpion Centruroides hirsutipalpus (Scorpiones; Buthidae) Affect the Function of Sodium Channels of Mammals

Abstract

1. Introduction

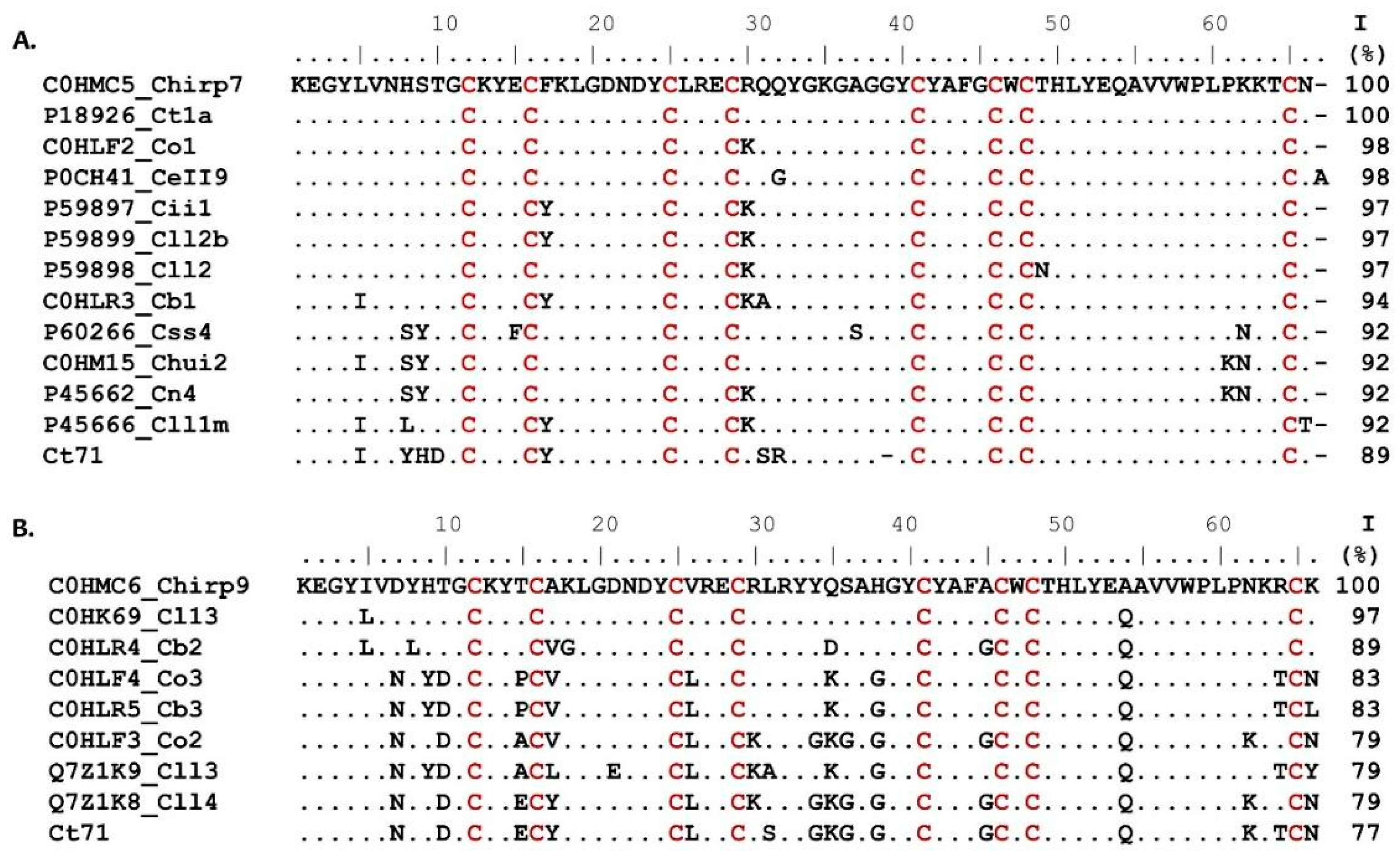

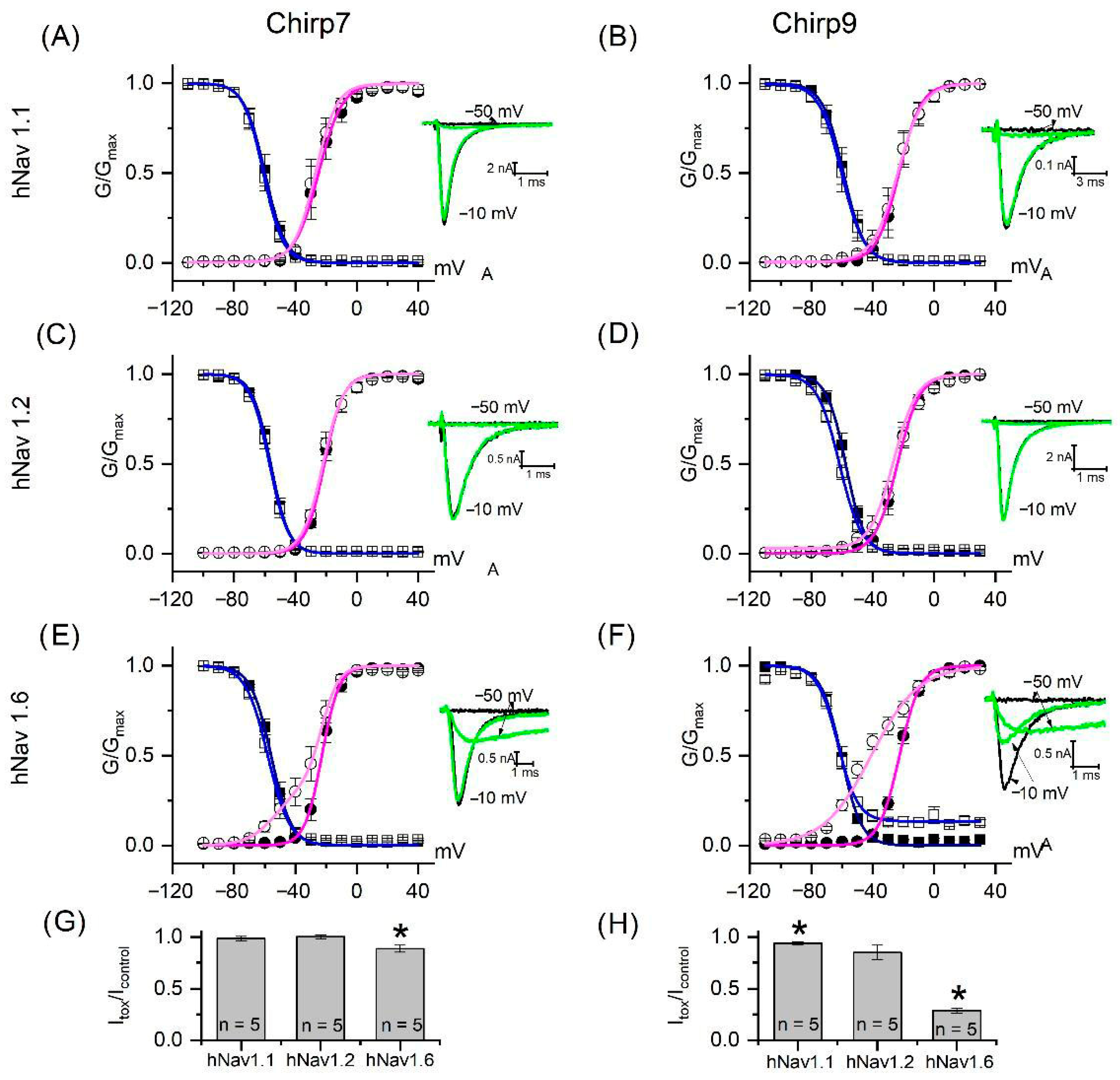

2. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Biological Material

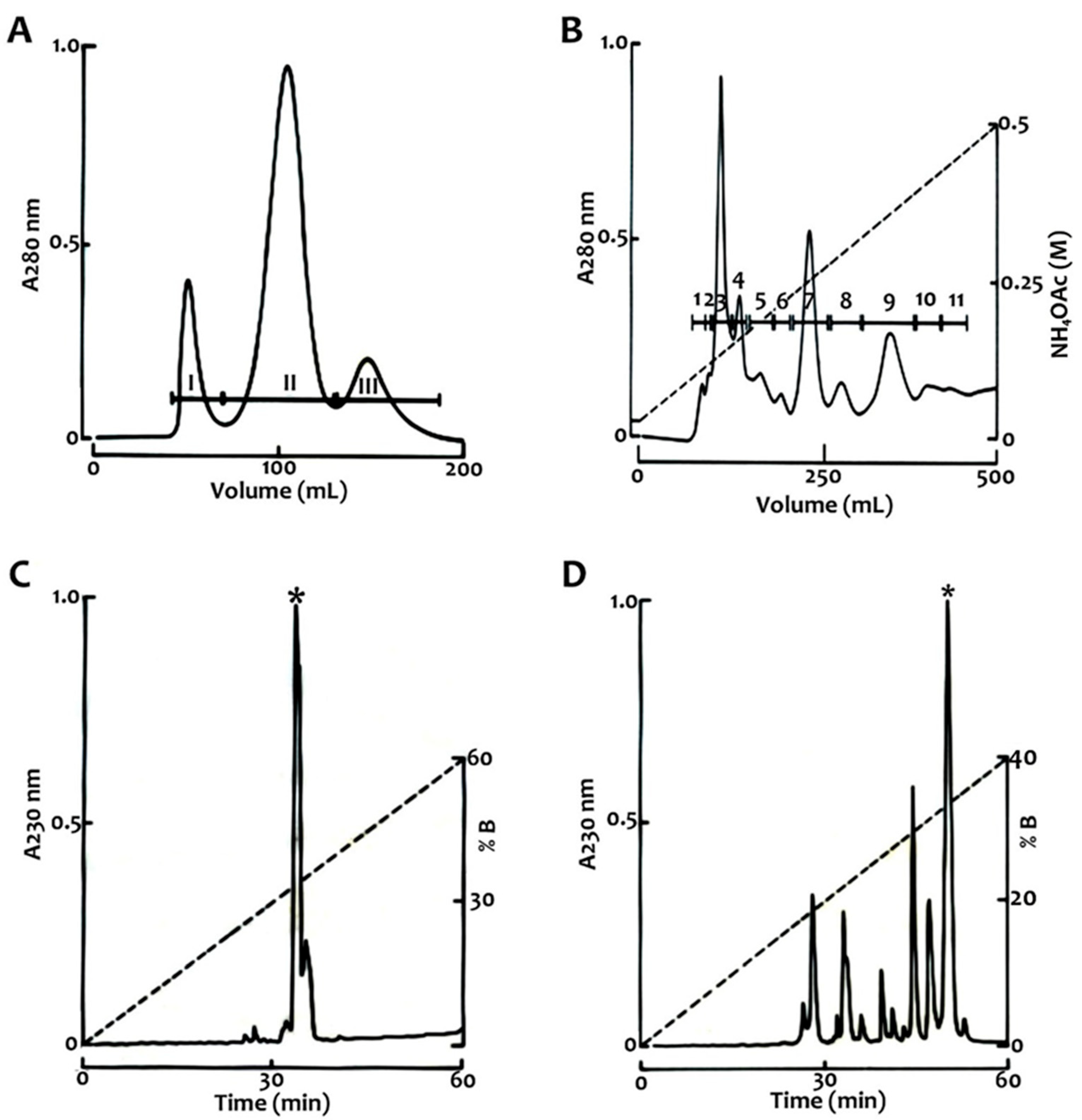

4.2. Venom Fractionation and Purification of Toxins

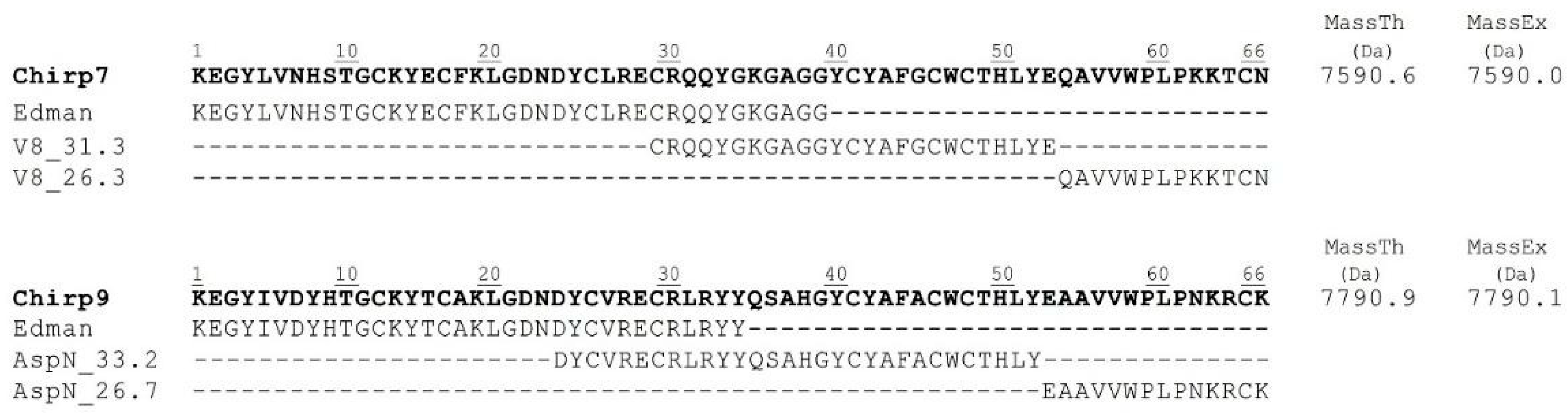

4.3. Toxin Sequencing by Edman Degradation

4.4. Biological Assays

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Joshi, S.; Surana, K.; Singh, S.; Lade, A.; Arote, N. Chemistry of Scorpion Venom and Its Medicinal Potential. Biol. Med. Chem. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Petricevich, V.L. Scorpion Venom and the Inflammatory Response. Mediat. Inflamm. 2010, 2010, 903295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isbister, G.K.; Bawaskar, H.S. Scorpion envenomation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevitz, M.; Froy, O.; Zilberberg, N.; Turkov, M.; Strugatsky, D.; Gershburg, E.; Lee, D.; Adams, M.E.; Tugarinov, V.; Anglister, J.; et al. Sodium channel modifiers from scorpion venom: Structure—Activity relationship, mode of action and application. Toxicon 1998, 36, 1671–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L.C.; Viana, G.M.M.; Nencioni, A.L.A.; Pimenta, D.C.; Beraldo-Neto, E. Scorpion peptides and ion channels: An insightful review of mechanisms and drug development. Toxins 2023, 15, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, A.; Varela, D. Voltage-Gated K+/Na+ Channels and Scorpion Venom Toxins in Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.; Savarin, P.; Gurevitz, M.; Zinn-Justin, S. Functional Anatomy of Scorpion Toxins Affecting Sodium Channels. J. Toxicol. Toxin Rev. 1998, 17, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosmans, F.; Tytgat, J. Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Modulation by Scorpion α-Toxins. Toxicon 2007, 49, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Lei, Y.; Qin, H.; Cao, Z.; Kwok, H.F. Deciphering scorpion toxin-induced pain: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic insights. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 2921–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Saavedra, J.; Francke, O.F. Descripción de una especie nueva de alacrán con importancia médica del género Centruroides (Scorpiones: Buthidae) del estado de Colima, México. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2009, 80, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Velázquez, L.L.; Cid-Uribe, J.; Romero-Gutierrez, M.T.; Olamendi-Portugal, T.; Jimenez-Vargas, J.M.; Possani, L.D. Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analyses of the Venom and Venom Glands of Centruroides Hirsutipalpus, a Dangerous Scorpion from Mexico. Toxicon 2020, 179, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Velázquez, L.L.; Olamendi-Portugal, T.; Restano-Cassulini, R.; Zamudio, F.Z.; Possani, L.D. Mass Fingerprinting and Electrophysiological Analysis of the Venom from the Scorpion Centruroides hirsutipalpus (Scorpiones: Buthidae). J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Trop. Dis. 2018, 24, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamilla, J.; Jiménez-Vargas, J.M.; Galván-Hernández, A.R.; Reyes-Méndez, M.E.; Bermúdez-Gúzman, M.J.; Restano-Cassulini, R.; Olamendi-Portugal, T.; Zamudio, F.Z.; Possani, L.D.; Valdez-Velázquez, L.L. Toxin Ct1a, from Venom of Centruroides Tecomanus, Modifies the Spontaneous Firing Frequency of Neurons in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus. Toxicon 2021, 197, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, E.; Velásquez, L.; Rivera, C. Separación e identificación de algunas toxinas del veneno de Centruroides margaritatus (Gervais, 1841) (Scorpiones: Buthidae). Rev. Peru. Biol. 2003, 10, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, V.A.; Cremonez, C.M.; Anjolette, F.A.P.; Aguiar, J.F.; Varanda, W.A.; Arantes, E.C. Functional and Structural Study Comparing the C-Terminal Amidated β-Neurotoxin Ts1 with Its Isoform Ts1-G Isolated from Tityus Serrulatus Venom. Toxicon 2014, 83, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catterall, W.A. Molecular Properties of Voltage-Sensitive Sodium Channels. In New Insights into Cell and Membrane Transport Processes; Poste, G., Crooke, S.T., Eds.; New Horizons in Therapeutics; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1986; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cestèle, S.; Qu, Y.; Rogers, J.C.; Rochat, H.; Scheuer, T.; Catterall, W.A. Voltage Sensor–Trapping: Enhanced Activation of Sodium Channels by β-Scorpion Toxin Bound to the S3–S4 Loop in Domain II. Neuron 1998, 21, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cestèle, S.; Yarov-Yarovoy, V.; Qu, Y.; Sampieri, F.; Catterall, W.A. Structure and Function of the Voltage Sensor of Sodium Channels Probed by a β-Scorpion Toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 21332–21344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Z.; Yarov-Yarovoy, V.; Scheuer, T.; Karbat, I.; Cohen, L.; Gordon, D.; Gurevitz, M.; Catterall, W.A. Structure-Function Map of the Receptor Site for β-Scorpion Toxins in Domain II of Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 33641–33651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billen, B.; Bosmans, F.; Tytgat, J. Animal peptides targeting voltage-activated sodium channels. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 2492–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.; Ilan, N.; Zilberberg, N.; Gilles, N.; Urbach, D.; Cohen, L.; Karbat, I.; Froy, O.; Gaathon, A.; Kallen, R.G.; et al. An ‘Old World’ scorpion beta-toxin that recognizes both insect and mammalian sodium channels. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003, 270, 2663–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bende, N.; Dziemborowicz, S.; Mobli, M.; Herzig, V.; Bosmans, F.; King, G.F.; Nicholson, G.M.; Escoubas, P. A distinct sodium channel voltage-sensor locus determines insect selectivity of the spider toxin Dc1a. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Cao, Z.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Li, W. Adaptive evolution of insect-selective excitatory β-type sodium channel toxins. Toxicon 2017, 123, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Di, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, W. Overview of Scorpion Species from China and Their Toxins. Toxins 2014, 6, 796–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavon, E.; Pedraza-Escalona, M.; Gurrola, G.B.; Olamendi-Portugal, T.; Corzo, G.; Wanke, E.; Possani, L.D. Negative-Shift Activation, Current Reduction and Resurgent Currents Induced by β-Toxins from Centruroides Scorpions in Sodium Channels. Toxicon 2012, 59, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, E.P.; Wilson, D.; Seymour, J.E. The influence of ecological factors on cnidarian venoms. Toxicon X 2021, 9–10, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaño-Umbarila, L.; Romero-Moreno, J.A.; Possani, L.D.; Becerril, B. State of the art on the development of a recombinant antivenom against Mexican scorpion stings. Toxicon 2025, 257, 108306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Guerrero, I.A.; Cárcamo-Noriega, E.; Gómez-Lagunas, F.; González-Santillán, E.; Zamudio, F.Z.; Gurrola, G.B.; Possani, L.D. Biochemical Characterization of the Venom from the Mexican Scorpion Centruroides Ornatus, a Dangerous Species to Humans. Toxicon 2020, 173, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandendriessche, T.; Olamendi-Portugal, T.; Zamudio, F.Z.; Possani, L.D.; Tytgat, J. Isolation and characterization of two novel scorpion toxins: The alpha-toxin-like CeII8, specific for Na(v)1.7 channels and the classical anti-mammalian CeII9, specific for Na(v)1.4 channels. Toxicon 2010, 56, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehesa-Dávila, M.; Martin, B.M.; Nobile, M.; Prestipino, G.; Possani, L.D. Isolation of a Toxin from Centruroides Infamatus Infamatus Koch Scorpion Venom That Modifies Na+ Permeability on Chick Dorsal Root Ganglion Cells. Toxicon 1994, 32, 1487–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cestèle, S.; Scheuer, T.; Mantegazza, M.; Rochat, H.; Catterall, W.A. Neutralization of Gating Charges in Domain II of the Sodium Channel Subunit Enhances Voltage-Sensor Trapping by a -Scorpion Toxin. J. Gen. Physiol. 2001, 118, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, E.; Prestipino, G.; Franciolini, F.; Dent, M.A.; Possani, L.D. Selective modification of the squid axon Na currents by Centruroides noxius toxin II-10. J. Physiol. 1984, 79, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Olamendi-Portugal, T.; Restano-Cassulini, R.; Riaño-Umbarila, L.; Becerril, B.; Possani, L.D. Functional and Immuno-Reactive Characterization of a Previously Undescribed Peptide from the Venom of the Scorpion Centruroides Limpidus. Peptides 2017, 87, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipold, E.; Borges, A.; Heinemann, S.H. Scorpion β-Toxin Interference with NaV Channel Voltage Sensor Gives Rise to Excitatory and Depressant Modes. J. Gen. Physiol. 2012, 139, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catterall, W.A.; Cestèle, S.; Yarov-Yarovoy, V.; Yu, F.H.; Konoki, K.; Scheuer, T. Voltage-Gated Ion Channels and Gating Modifier Toxins. Toxicon 2007, 49, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edman, P.; Begg, G. A protein sequenator. Eur. J. Biochem. 1967, 1, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

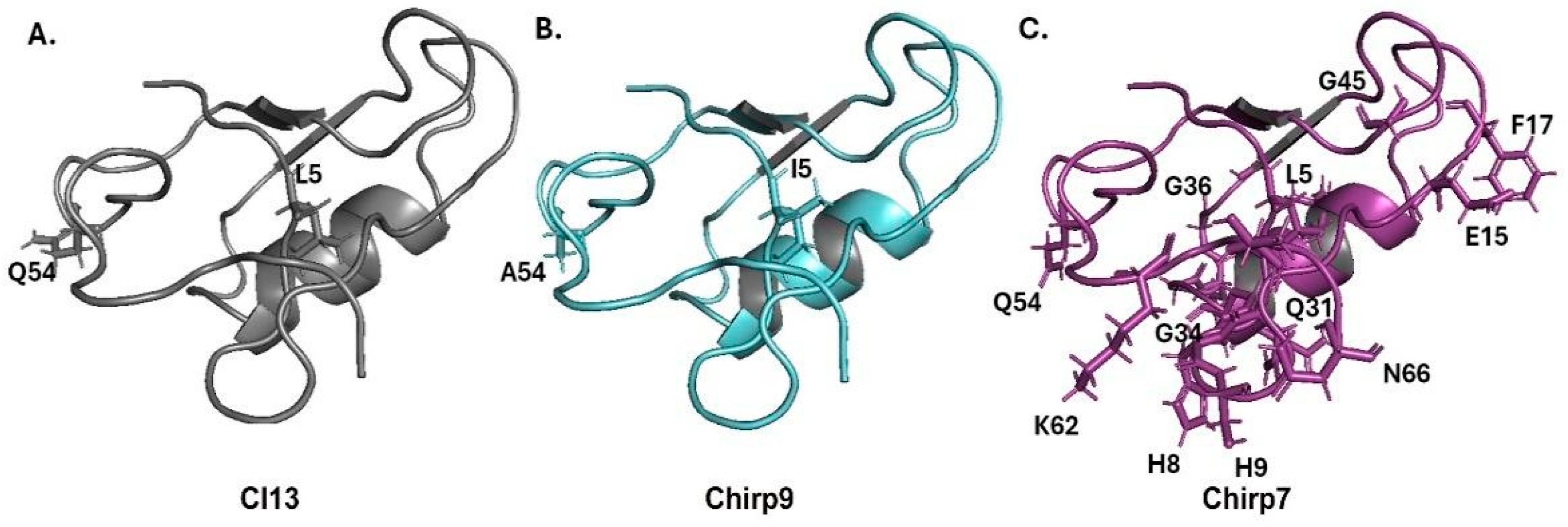

- Zhou, X.; Zheng, W.; Li, Y.; Pearce, R.; Zhang, C.; Bell, E.W.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y. I-TASSER-MTD: A deep-learning-based platform for multi-domain protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 2326–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

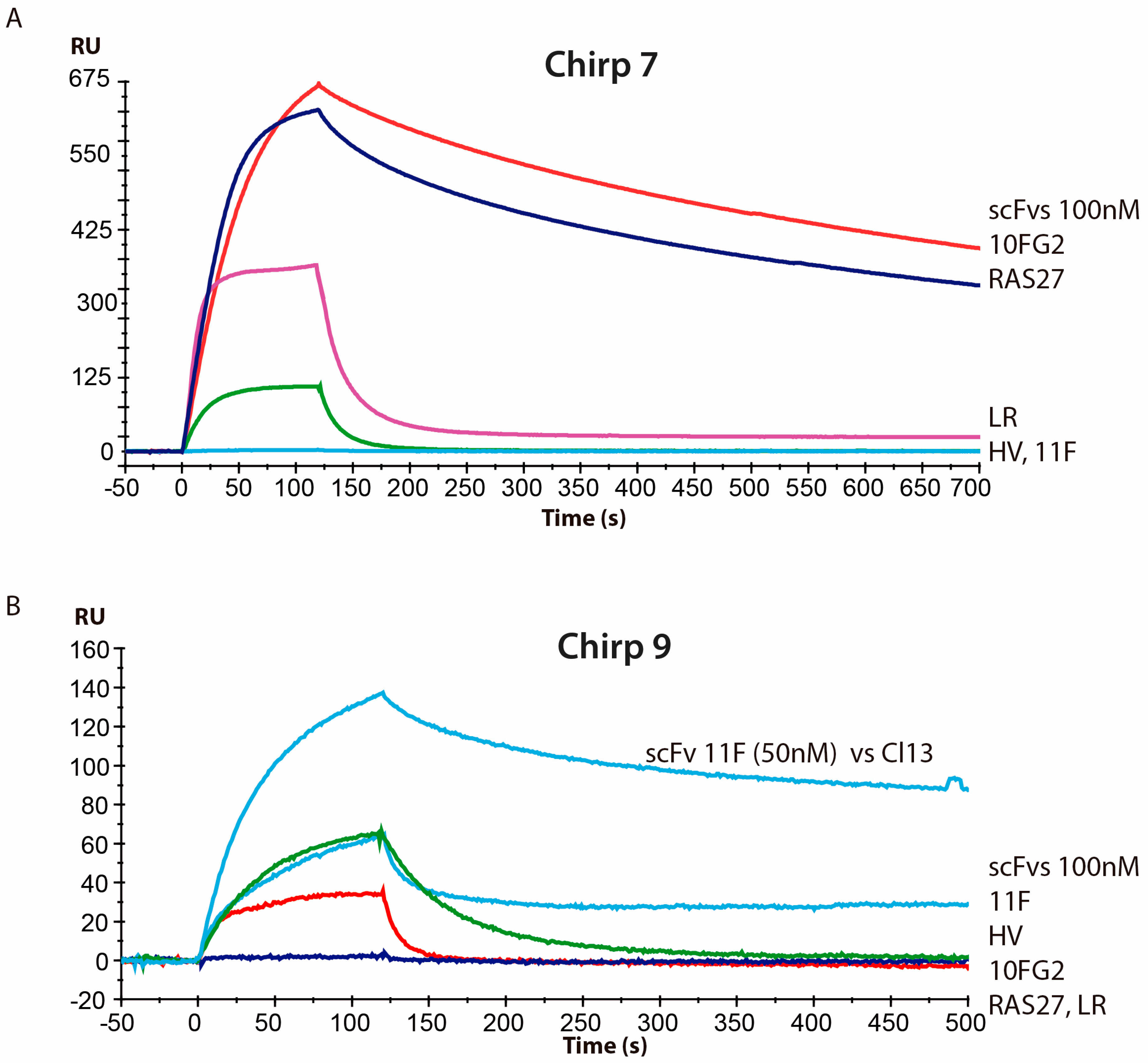

- Torreri, P.; Ceccarini, M.; Macioce, P.; Petrucci, T.C. Biomolecular Interactions by Surface Plasmon Resonance Technology. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanità 2005, 41, 437–441. [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell, J.M. Surface plasmon resonance: Towards an understanding of the mechanisms of biological molecular recognition. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2001, 5, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.H.; Park, J.; Kang, S.; Kim, M. Surface plasmon resonance: A versatile technique for biosensor applications. Sensors 2015, 15, 10481–10510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fraction | RT (HPLC, min) | Mass (Da) | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| FII.1 | 34.12 | 7108.9 | Slightly toxic |

| FII.2 | 28.33 | 7050 | Non-toxic |

| FII.3 | 28.4 | 6604.09 | - |

| FII.4 | 32.26 | 7155.58 | - |

| FII.5 | 32–38.5 * | 7591.4 | Toxic |

| FII.6 | 32–38.5 * | 7591.4 | - |

| FII.7 (Chirp7) | 35.8 | 7590 | Lethal |

| FII.8 | 29.96 | 7559 | - |

| FII.9 (Chirp9) | 50.4 | 7790.1 | Lethal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valdez-Velazquez, L.L.; Olamendi-Portugal, T.; Restano-Cassulini, R.; Riaño-Umbarila, L.; Jiménez-Vargas, J.M.; Zamudio, F.; Salazar-Monge, H.; Becerril, B.; Possani, L.D. Beta Toxins Isolated from the Scorpion Centruroides hirsutipalpus (Scorpiones; Buthidae) Affect the Function of Sodium Channels of Mammals. Toxins 2025, 17, 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120584

Valdez-Velazquez LL, Olamendi-Portugal T, Restano-Cassulini R, Riaño-Umbarila L, Jiménez-Vargas JM, Zamudio F, Salazar-Monge H, Becerril B, Possani LD. Beta Toxins Isolated from the Scorpion Centruroides hirsutipalpus (Scorpiones; Buthidae) Affect the Function of Sodium Channels of Mammals. Toxins. 2025; 17(12):584. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120584

Chicago/Turabian StyleValdez-Velazquez, Laura L., Timoteo Olamendi-Portugal, Rita Restano-Cassulini, Lidia Riaño-Umbarila, Juana María Jiménez-Vargas, Fernando Zamudio, Hermenegildo Salazar-Monge, Baltazar Becerril, and Lourival D. Possani. 2025. "Beta Toxins Isolated from the Scorpion Centruroides hirsutipalpus (Scorpiones; Buthidae) Affect the Function of Sodium Channels of Mammals" Toxins 17, no. 12: 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120584

APA StyleValdez-Velazquez, L. L., Olamendi-Portugal, T., Restano-Cassulini, R., Riaño-Umbarila, L., Jiménez-Vargas, J. M., Zamudio, F., Salazar-Monge, H., Becerril, B., & Possani, L. D. (2025). Beta Toxins Isolated from the Scorpion Centruroides hirsutipalpus (Scorpiones; Buthidae) Affect the Function of Sodium Channels of Mammals. Toxins, 17(12), 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120584