Update on Non-Interchangeability of Botulinum Neurotoxin Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Trade Name(s) | Nonproprietary USAN Name | Manufacturer | Serotype | Complex Size or NT Only | Formulation | Selected Regions Approved * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercially available | ||||||

| BOTOX®, BOTOX® Cosmetic, Vistabel®, Vistabex® [4,6] | OnabotulinumtoxinA | Allergan/AbbVie | A | ~900 kDa | In 100 U vial

| USA, Canada, EU, China, Japan, South Korea, Brazil |

| Dysport®, Azzalure® [7,8] | AbobotulinumtoxinA | Ipsen | A | ~400 kDa ** | In 500 U vial

| USA, Canada, EU, China, South Korea, Brazil |

| Xeomin®, Boucouture® [9] | IncobotulinumtoxinA | Merz | A | ~150 kDa | In 100 U vial

| USA, Canada, EU, Japan, South Korea, Brazil |

| Nabota®, Jeuveau®, Nuceiva® [10,11] | PrabotulinumtoxinA | Evolus/Daewoong | A | ~900 kDa | In 100 U vial

| USA, Canada, EU, South Korea, Brazil |

| Daxxify™ [12] | DaxibotulinumtoxinA-lanm | Revance | A | ~150 kDa | In 100 U vial

| USA |

| Myobloc® [13,14] | RimabotulinumtoxinB | Solstice | B | ~700 kDa | In 5000 U vial

| USA, Canada |

| AlluzienceTM (EU) [8,15] | AbobotulinumtoxinA solution for injection | Ipsen | A | ~400 kDa |

| EU |

| Neuronox®/Meditoxin® | Unassigned | Medytox | A | NR | Information from the manufacturer could not be identified. | South Korea, Brazil |

| Innotox® | Unassigned | Medytox | A | NR | Information from the manufacturer could not be identified. | South Korea (approved in 2018; product not available at the time of manuscript submission) |

| Botulax® (Korea) [16], Letybo® [17] EU: 50 U vial only | LetibotulinumtoxinA | Hugel | A | NR | In 100 U vial

| Canada, EU, China, South Korea, USA |

| Relatox® [18] | None established | Microgen | A | NR | In 100 U vial:

| Russia |

| Hutox® (Liztox®) [19] | None established | Huons | A | 900 kDa | NR | South Korea |

| Lantox® (Hengli®, Prosigne®, Lantox®, Lazox® Redux®, Liftox®) [20,21,22] | None established | Lanzhou | A | 900 kDa | In 100 U vial:

| EU, China, South Korea, Brazil |

| In Development | ||||||

| NR [23,24] | RelabotulinumtoxinA | Galderma | A | ~150 kDa |

| |

| NR [25,26] | TrenibotulinumtoxinE | Allergan Aesthetics, an AbbVie company | E | NR | NR |

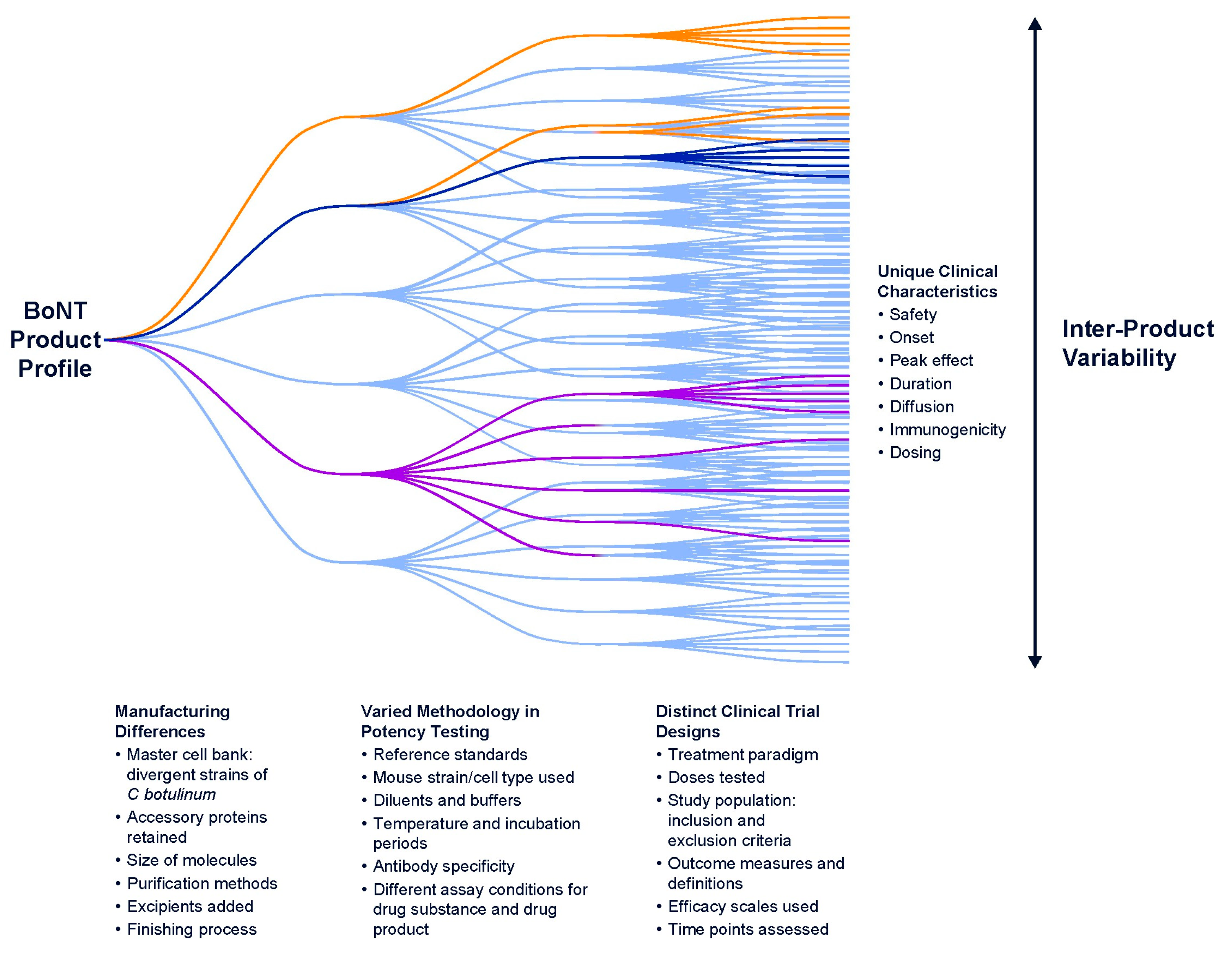

2. Properties of Botulinum Neurotoxins

2.1. Structure

2.2. Mechanism of Action

2.3. Serotypes

2.4. Role of NAPs in the Pharmacodynamic Action of BoNTs

3. Transforming BoNTs into Medications

3.1. Bacterial Strain

3.2. Fermentation

3.3. Purification

3.4. Unit Testing Procedures

3.5. Excipients and Formulation—Generating the Drug Product

3.6. Pre-Release Unit Testing

4. Botulinum Neurotoxin Potency

4.1. Definition of a Unit

4.2. Potency Reference Standards

4.3. Cell Based Potency Assays

4.4. Examples of Differences in Potency among BoNTAs

4.5. No Fixed Dose Ratios

5. Botulinum Neurotoxin Dose Response

6. BoNT Onset of Effect

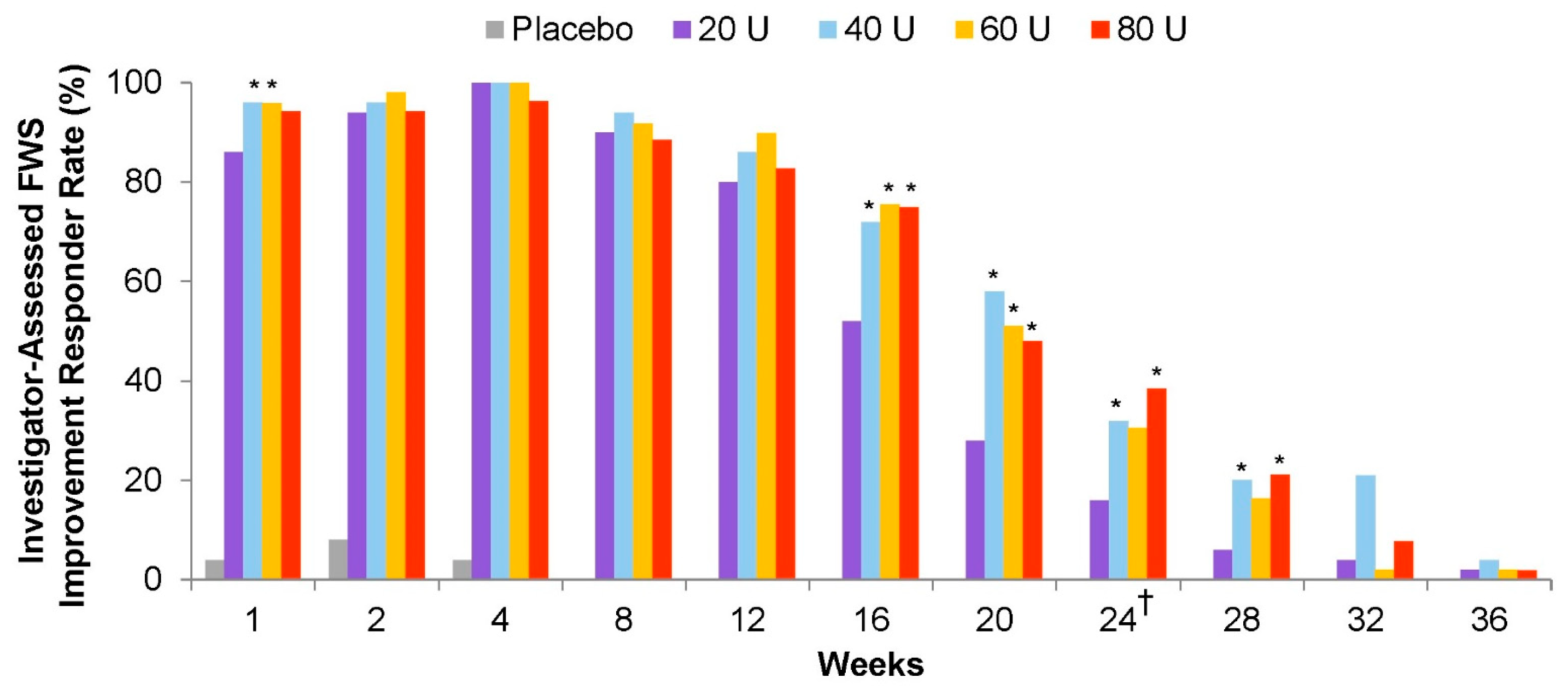

7. BoNT Efficacy and Duration of Action

7.1. Influence of Intrinsic Product Differences

7.1.1. Serotype/Subtype

Persistence of Type A Light Chain

Site of SNAP-25 Cleavage

7.1.2. Formulation and Unit Potency

7.2. Influence of Peripheral Neuron Type

7.3. Influence of Study-Level Factors

7.3.1. Patient Population

7.3.2. Dose Differences

7.3.3. Treatment Paradigms

7.3.4. Assessments of Efficacy and Duration

7.3.5. Rating Scales and Raters

7.3.6. Follow-Up Timepoints

7.4. Summary of Study-Level Variables

8. BoNT Safety and Adverse Events

9. Immunogenicity

9.1. Factors Affecting Neutralizing Antibody Formation

9.2. Secondary Non-Response: Usually Not Due to Neutralizing Antibodies

9.3. Clinical Implications of Neutralizing Antibody Formation?

10. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scott, A.B. Botulinum toxin injection into extraocular muscles as an alternative to strabismus surgery. Ophthalmology 1980, 87, 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, A.B.; Kennedy, R.A.; Stubbs, H.A. Botulinum A toxin injection as a treatment for blepharospasm. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1985, 103, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allergan. BOTOX® Cosmetic (OnabotulinumtoxinA) Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/botox-cosmetic_pi.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Allergan. BOTOX® (OnabotulinumtoxinA) Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/botox_pi.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Brin, M.F.; James, C.; Maltman, J. Botulinum toxin type A products are not interchangeable: A review of the evidence. Biologics 2014, 8, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Lin, W.J.; Li, S.; Aoki, K.R. Complete DNA sequences of the botulinum neurotoxin complex of Clostridium botulinum type A-Hall (Allergan) strain. Gene 2003, 315, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipsen. DYSPORT® (AbobotulinumtoxinA) Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.ipsen.com/websites/ipsen_online/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/10002305/dys-us-004998_dysport-pi-july-2020.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- CDER Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Application Number 125274. Chemistry Reviews. BLA STN 125286/0 Reloxin (Botulinum Toxin Type A). Ipsen Biopharm Limited, UK. 29 April 2009. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2009/125274Orig1s001Approv.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Merz. XEOMIN® (IncobotulinumtoxinA) Prescribing Information. Available online: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=ccdc3aae-6e2d-4cd0-a51c-8375bfee9458&type=display (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Beer, K.R.; Shamban, A.T.; Avelar, R.L.; Gross, J.E.; Jonker, A. Efficacy and Safety of PrabotulinumtoxinA for the Treatment of Glabellar Lines in Adult Subjects: Results From 2 Identical Phase III Studies. Dermatol. Surg. 2019, 45, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evolus. JEUVEAUTM (PrabotulinumtoxinA-xvfs) Prescribing Information. Available online: https://info.evolus.com/hubfs/Jeuveau_USPI.pdf?_ga=2.8849718.2048714185.1598806029-1772010453.1597802867 (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Revance. DAXXIFY® (DaxibotulinumtoxinA-lanm) Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.revance.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/daxi-pi-and-med-guide.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Solstice. Myobloc® Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.myoblochcp.com/files/myobloc-prescribing-information.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Setler, P. The biochemistry of botulinum toxin type B. Neurology 2000, 55 (Suppl. S5), S22–S28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ascher, B.; Kestemont, P.; Boineau, D.; Bodokh, I.; Stein, A.; Heckmann, M.; Dendorfer, M.; Pavicic, T.; Volteau, M.; Tse, A.; et al. Liquid Formulation of AbobotulinumtoxinA Exhibits a Favorable Efficacy and Safety Profile in Moderate to Severe Glabellar Lines: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo- and Active Comparator-Controlled Trial. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2018, 38, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugel. Hugel, Inc. Botulax® Prescribing Information. 2013. Available online: www.hugel.co.kr (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Croma. Croma Aesthetics Canada, Ltd. LetyboTM (LetibutlinumtoxinA for Injection) Product Monograph. Available online: https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00066317.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Microgen. Botulinum Toxin Type A in Combination with Hemagglutinin. Available online: https://www.microgen.ru/en/products/anatoksiny-toksiny/toksin-botulinicheskiy-tipa-a-v-komplekse-s-gemagglyutininom/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Huons. Introduction. Available online: https://huonsglobal.com/eng/home.php?go=amenu_04 (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Dressler, D.; Pan, L.; Su, J.; Teng, F.; Jin, L. Lantox-The Chinese Botulinum Toxin Drug-Complete English Bibliography and Comprehensive Formalised Literature Review. Toxins 2021, 13, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzhou. BTXA Prescribing Information (Not Approved in the US). Available online: https://www.btxa.com/discover/what/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- He, X.; Miao, C.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. Biological characteristics and quality of bltulinum toxin type A for injection. Chin. J. Biol. 2012, 25, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Monheit, G.D.; Nestor, M.S.; Cohen, J.; Goldman, M.P.; Gold, M.H.; Tichy, E.H.; Swinyer, L. Evaluation of QM1114, a novel ready-to-use liquid botulinum toxin, in aesthetic treatment of glabellar lines. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, AB27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljegren Sundberg, A.; Stahl, U. Relabotulinum toxin—A novel, high purity BoNT-A1 in liquid formulation. In Proceedings of the Toxins 2021 Virtual Conference, Virtual, 16–17 January 2021; Available online: https://www.neurotoxins.org/toxins-2021-virtual/posters/entry/16100/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Alam, M.; Vitarella, D.; Ahmad, W.; Abushakra, S.; Mao, C.; Brin, M.F. Botulinum Toxin Type E Associated With Reduced Itch and Pain During Wound Healing and Acute Scar Formation Following Excision and Linear Repair on the Forehead: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 89, 1317–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbvie. Allergan Aesthetics Announces Positive Topline Results from Two Pivotal Phase 3 Studies of TrenibotulinumtoxinE (BoNT/E) for the Treatment of Glabellar Lines. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/allergan-aesthetics-announces-positive-topline-results-from-two-pivotal-phase-3-studies-of-trenibotulinumtoxine-bonte-for-the-treatment-of-glabellar-lines-301965107.html. (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Wee, S.Y.; Park, E.S. Immunogenicity of botulinum toxin. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2022, 49, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambleton, P.; Capel, B.; Bailey, N.; Heron, N.; Crooks, A.; Melling, J.; Tse, C.K.; Dolly, J. Production, purification and toxoiding of Clostridium botulinum type A toxin. In Biomedical Aspects of Botulism; Lewis, G.E.J., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, D.M. Bacterial toxins: A table of lethal amounts. Microbiol. Rev. 1982, 46, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, K.; Yoneyama, T.; Suzuki, T.; Kouguchi, H.; Inui, K.; Niwa, K.; Watanabe, T.; Ohyama, T. Expression and stability of the nontoxic component of the botulinum toxin complex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 384, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Rumpel, S.; Zhou, J.; Strotmeier, J.; Bigalke, H.; Perry, K.; Shoemaker, C.B.; Rummel, A.; Jin, R. Botulinum neurotoxin is shielded by NTNHA in an interlocked complex. Science 2012, 335, 977–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, S.; Jin, R. Assembly and function of the botulinum neurotoxin progenitor complex. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013, 364, 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pirazzini, M.; Rossetto, O.; Eleopra, R.; Montecucco, C. Botulinum neurotoxins: Biology, pharmacology, and toxicology. Pharmacol. Rev. 2017, 69, 200–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalb, S.R.; Baudys, J.; Smith, T.J.; Smith, L.A.; Barr, J.R. Characterization of hemagglutinin negative botulinum progenitor toxins. Toxins 2017, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuchs, J. Beitrage zur kentniss die toxin und antitoxin des Bacillus botulinus. Z. Hyg. Infekt. 1910, 65, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, G.S. Notes on Bacillus botulinus. J. Bacteriol. 1919, 4, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, L.; Brin, M.F.; Brideau-Andersen, A. Novel Native and Engineered Botulinum Neurotoxins. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2021, 263, 63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, F.W.; Lamanna, C.; Sharp, D.G. Molecular weight and homogeneity of crystalline botulinus A toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 1946, 165, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugii, S.; Sakaguchi, G. Molecular construction of Clostridium botulinum type A toxins. Infect. Immun. 1975, 12, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugii, S.; Ohishi, I.; Sakaguchi, G. Oral toxicities of Clostridium botulinum toxins. Jpn. J. Med. Sci. Biol. 1977, 30, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lietzow, M.A.; Gielow, E.T.; Le, D.; Zhang, J.; Verhagen, M.F. Subunit stoichiometry of the Clostridium botulinum type A neurotoxin complex determined using denaturing capillary electrophoresis. Protein J. 2008, 27, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Singh, B.R. Hemagglutinin binding mediated protection of botulinum neurotoxin from proteolysis. J. Nat. Toxins 1998, 7, 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Kuziemko, G.M.; Amersdorfer, P.; Wong, C.; Marks, J.D.; Stevens, R.C. Antibody mapping to domains of botulinum neurotoxin serotype A in the complexed and uncomplexed forms. Infect. Immun. 1997, 65, 1626–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacy, D.B.; Tepp, W.; Cohen, A.C.; DasGupta, B.R.; Stevens, R.C. Crystal structure of botulinum neurotoxin type A and implications for toxicity. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998, 5, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Gu, S.; Jin, L.; Le, T.T.; Cheng, L.W.; Strotmeier, J.; Kruel, A.M.; Yao, G.; Perry, K.; Rummel, A.; et al. Structure of a bimodular botulinum neurotoxin complex provides insights into its oral toxicity. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Montal, M. Crucial role of the disulfide bridge between botulinum neurotoxin light and heavy chains in protease translocation across membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 29604–29611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montal, M. Botulinum neurotoxin: A marvel of protein design. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010, 79, 591–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaker, H.; Zhang, S.; Diamond, D.A.; Dong, M. Beyond botulinum neurotoxin A for chemodenervation of the bladder. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2021, 31, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, O.; Pirazzini, M.; Montecucco, C. Botulinum neurotoxins: Genetic, structural and mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrandiz-Huertas, C.; Mathivanan, S.; Wolf, C.J.; Devesa, I.; Ferrer-Montiel, A. Trafficking of ThermoTRP Channels. Membranes 2014, 4, 525–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winner, B.M.; Bodt, S.M.L.; McNutt, P.M. Special Delivery: Potential Mechanisms of Botulinum Neurotoxin Uptake and Trafficking within Motor Nerve Terminals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, M.J.; Purkiss, J.R.; Foster, K.A. Sensitivity of embryonic rat dorsal root ganglia neurons to Clostridium botulinum neurotoxins. Toxicon 2000, 38, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durham, P.L.; Cady, R.; Cady, R. Regulation of calcitonin gene-related peptide secretion from trigeminal nerve cells by botulinum toxin type A: Implications for migraine therapy. Headache 2004, 44, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morenilla-Palao, C.; Planells-Cases, R.; Garcia-Sanz, N.; Ferrer-Montiel, A. Regulated exocytosis contributes to protein kinase C potentiation of vanilloid receptor activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 25665–25672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, R.; Blumenfeld, A.M.; Silberstein, S.D.; Manack Adams, A.; Brin, M.F. Mechanism of Action of OnabotulinumtoxinA in Chronic Migraine: A Narrative Review. Headache 2020, 60, 1259–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacky, B.P.S.; Garay, P.E.; Dupuy, J.; Nelson, J.B.; Cai, B.; Molina, Y.; Wang, J.; Steward, L.E.; Broide, R.S.; Francis, J.; et al. Identification of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) as a protein receptor for botulinum neurotoxin serotype A (BoNT/A). PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, N.G.; Malik, S.; Sanstrum, B.J.; Rhéaume, C.; Broide, R.S.; Jameson, D.M.; Brideau-Andersen, A.; Jacky, B.S. Characterization of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin serotype A (BoNT/A) and fibroblast growth factor receptor interactions using novel receptor dimerization assay. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutson, R.A.; Collins, M.D.; East, A.K.; Thompson, D.E. Nucleotide sequence of the gene coding for non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum type B neurotoxin: Comparison with other clostridial neurotoxins. Curr. Microbiol. 1994, 28, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulain, B.; Lemichez, E.; Popoff, M.R. Neuronal selectivity of botulinum neurotoxins. Toxicon 2020, 178, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karalewitz, A.P.; Fu, Z.; Baldwin, M.R.; Kim, J.J.; Barbieri, J.T. Botulinum neurotoxin serotype C associates with dual ganglioside receptors to facilitate cell entry. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 40806–40816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, R.; Zhang, X.; Levy, D.; Aoki, K.R.; Brin, M.F. Selective inhibition of meningeal nociceptors by botulinum neurotoxin type A: Therapeutic implications for migraine and other pains. Cephalalgia 2014, 34, 853–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukreja, R.V.; Singh, B.R. Comparative role of neurotoxin-associated proteins in the structural stability and endopeptidase activity of botulinum neurotoxin complex types A and E. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 14316–14324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugii, S.; Ohishi, I.; Sakaguchi, G. Correlation between oral toxicity and in vitro stability of Clostridium botulinum type A and B toxins of different molecular sizes. Infect. Immun. 1977, 16, 910–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohishi, I.; Sugii, S.; Sakaguchi, G. Oral toxicities of Clostridium botulinum toxins in response to molecular size. Infect. Immun. 1977, 16, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.K.; Singh, B.R. Enhancement of the endopeptidase activity of purified botulinum neurotoxins A and E by an isolated component of the native neurotoxin associated proteins. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 4791–4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, K.J.; Patel, K.; Singh, B.R.; Hale, M.L. Role of critical elements in botulinum neurotoxin complex in toxin routing across intestinal and bronchial barriers. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Zhong, X.; Gu, S.; Kruel, A.M.; Dorner, M.B.; Perry, K.; Rummel, A.; Dong, M.; Jin, R. Molecular basis for disruption of E-cadherin adhesion by botulinum neurotoxin A complex. Science 2014, 344, 1405–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Foss, S.; Lindo, P.; Sarkar, H.; Singh, B.R. Hemagglutinin-33 of type A botulinum neurotoxin complex binds with synaptotagmin II. FEBS J. 2005, 272, 2717–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamanna, C.; Spero, L.; Schantz, E.J. Dependence of time to death on molecular size of botulinum toxin. Infect. Immun. 1970, 1, 423–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Declerck, P.; Danesi, R.; Petersel, D.; Jacobs, I. The Language of Biosimilars: Clarification, Definitions, and Regulatory Aspects. Drugs 2017, 77, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. Scientific Considerations in Demonstrating Biosimilarity to a Reference Product. Guidance for Industry. 2015. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/scientific-considerations-demonstrating-biosimilarity-reference-product (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Keefe, R.S.; Kraemer, H.C.; Epstein, R.S.; Frank, E.; Haynes, G.; Laughren, T.P.; McNulty, J.; Reed, S.D.; Sanchez, J.; Leon, A.C. Defining a clinically meaningful effect for the design and interpretation of randomized controlled trials. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 10, 4S–19S. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Solish, N.; Carruthers, J.; Kaufman, J.; Rubio, R.G.; Gross, T.M.; Gallagher, C.J. Overview of DaxibotulinumtoxinA for Injection: A Novel Formulation of Botulinum Toxin Type A. Drugs 2021, 81, 2091–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, K.H.; Chun, M.H.; Paik, N.J.; Park, Y.G.; Lee, S.U.; Kim, M.W.; Kim, D.K. Safety and efficacy of letibotulinumtoxinA(BOTULAX(R)) in treatment of post stroke upper limb spasticity: A randomized, double blind, multi-center, phase III clinical trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCBI National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotehcnology Information. Clostridium botulinum Strain Hall Neurotoxin Type A Gene, Complete cds. GenBank: KJ997761.1. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/KJ997761.1 (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Hall, I.C. A Collection of Anaerobic Bacteria. Science 1928, 68, 141–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambleton, P.; Pickett, A.M.; Shone, C.C. Botulinum toxin: From menace to medicine. In Clinical Uses of Botulinum Toxins; Ward, A.B., Barnes, M.P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, P.K.; Raphael, B.H.; Maslanka, S.E.; Cai, S.; Singh, B.R. Analysis of genomic differences among Clostridium botulinum type A1 strains. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, A. Botulinum toxin as a clinical product: Manufacture and pharmacology. In Clinical Applications of Botulinum Neurotoxin; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4939-0261-3_2 (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Whitemarsh, R.C.M.; Tepp, W.H.; Bradshaw, M.; Lin, G.; Pier, C.L.; Scherf, J.M.; Johnson, E.A.; Pellett, S. Characterization of botulinum neurotoxin A subtypes 1 through 5 by investigation of activities in mice, in neuronal cell cultures, and in vitro. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 3894–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellett, S.; Tepp, W.H.; Whitemarsh, R.C.; Bradshaw, M.; Johnson, E.A. In vivo onset and duration of action varies for botulinum neurotoxin A subtypes 1-5. Toxicon 2015, 107, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, L.S.; Metzger, J.F. Toxin production by Clostridium botulinum type A under various fermentation conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1979, 38, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schantz, E.J.; Johnson, E.A. Properties and use of botulinum toxin and other microbial neurotoxins in medicine. Microbiol. Rev. 1992, 56, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wortzman, M.S.; Pickett, A. The science and manufacturing behind botulinum neurotoxin type A-ABO in clinical use. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2009, 29, S34–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frevert, J. Pharmaceutical, biological, and clinical properties of botulinum neurotoxin type A products. Drugs R&D 2015, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration. 21 Food Drugs Chapter I. Food and Drug Administration Department of Health and Human Services. Subchapter D Drugs for Human Use 2021. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/cfrsearch.cfm?fr=314.3# (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Brandau, D.T.; Joshi, S.B.; Smalter, A.M.; Kim, S.; Steadman, B.; Middaugh, C.R. Stability of the Clostridium botulinum type A neurotoxin complex: An empirical phase diagram based approach. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vulto, A.G.; Jaquez, O.A. The process defines the product: What really matters in biosimilar design and production? Rheumatology 2017, 56, iv14–iv29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, N. Myozyme Becomes Lumizyme after Biologics Scale-Up. Available online: https://www.outsourcing-pharma.com/article/2009/02/16/myozyme-becomes-lumizyme-after-biologics-scale-up (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Ratanji, K.D.; Derrick, J.P.; Kimber, I.; Thorpe, R.; Wadhwa, M.; Dearman, R.J. Influence of Escherichia coli chaperone DnaK on protein immunogenicity. Immunology 2017, 150, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidl, A.; Hainzl, O.; Richter, M.; Fischer, R.; Böhm, S.; Deutel, B.; Hartinger, M.; Windisch, J.; Casadevall, N.; London, G.M.; et al. Tungsten-induced denaturation and aggregation of epoetin alfa during primary packaging as a cause of immunogenicity. Pharm. Res. 2012, 29, 1454–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPEC The International Pharmaceutical Exceipients Council. General Glossary of Terms and Acronyms for Pharmaceutical Exceipients. Version 2. 2021. Available online: http://www.jpec.gr.jp/document/2014ipec_glossary_of_terms.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Malmirchegini, R.; Too, P.; Oliyai, C.; Joshi, A. Revance’s novel peptide excipient, RTP004, and its role in stabilizing DaxibotulinumtoxinA (DAXI) against aggregation. Toxicon 2018, 156 (Suppl. 1), S72–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.; Nicholson, G.; Broide, R.; Nino, C.; Do, M.; Wan, J.; Le, L.; Vazquez-Cintron, E.; Wu, C.; Nelson, M.; et al. A cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) did not decrease 150-kDa BoNT/A toxin adsorption to surfaces or increase toxin potency or duration in a prototype formulation [abstract]. Mov. Disord. 2021, 36 (Suppl. 1), 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austerberry, J.; Morrison, J.; Shubber, S.; Parreirinha, D.; Baig, H.; Lima, R.; Fox, I.; Wegner, K.; Molloy, E.; Higazi, D. Cell-penetrating peptides: Are they useful excipients in botulinum toxin formulations? Toxicon 2022, 214 (Suppl. S1), S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, K.; Das, R.E.; Ekong, T.A.; Sesardic, D. Therapeutic botulinum type A toxin: Factors affecting potency. Toxicon 1996, 34, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldman, S.A. Does potency predict clinical efficacy? Illustration through an antihistamine model. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002, 89, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubig, R.R.; Spedding, M.; Kenakin, T.; Christopoulos, A. International Union of Pharmacology Committee on Receptor Nomenclature and Drug Classification. XXXVIII. Update on terms and symbols in quantitative pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 2003, 55, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Pharmacopoeia Commission. European Pharmacopoeia 9.6. Botulinum Toxin Type A for Injection. Available online: https://file.wuxuwang.com/yaopinbz/EP9/EP9.6_01__91.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Hambleton, P.; Pickett, A.M. Potency equivalence of botulinum toxin preparations. J. R. Soc. Med. 1994, 87, 719. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dressler, D.; Mander, G.; Fink, K. Measuring the potency labelling of onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox((R))) and incobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin ((R))) in an LD50 assay. J. Neural Transm. 2012, 119, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesardic, D.; Leung, T.; Gaines Das, R. Role for standards in assays of botulinum toxins: International collaborative study of three preparations of botulinum type A toxin. Biologicals 2003, 31, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbert, P.A.; Johnson, B.J. Reference standards. In Separation Science and Technology; Ahuja, A., Mills Alsante, K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; Volume 5, pp. 119–143. [Google Scholar]

- USP. Insulins Are Critical Medicines—USP Standards Help Ensure Quality. Available online: https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/about/public-policy/insulin-usp.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- EDQM-USP. Joint EDQM-USP Symposium Illustrates Use of Pharmacopoeial Reference Standards. Available online: https://www.edqm.eu/en/d/85098 (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Fernandez-Salas, E.; Wang, J.; Molina, Y.; Nelson, J.B.; Jacky, B.P.; Aoki, K.R. Botulinum neurotoxin serotype A specific cell-based potency assay to replace the mouse bioassay. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellett, S. Progress in cell based assays for botulinum neurotoxin detection. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013, 364, 257–285. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp, D.; Canty, D.; Rhéaume, D.; Jacky, B.; Broide, R.; Brideau-Andersen, A. Greater biological activity and non-interchangeability of onabotulinumtoxinA compared with vacuum-dried prabotulinumtoxina. Toxicon 2021, 190 (Suppl. S1), S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.; Nicholson, G.; Canty, D.; Wang, J.; Rhéaume, C.; Le, L.; Steward, L.E.; Washburn, M.; Jacky, B.P.; Broide, R.S.; et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA Displays Greater Biological Activity Compared to IncobotulinumtoxinA, Demonstrating Non-Interchangeability in Both In Vitro and In Vivo Assays. Toxins 2020, 12, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, K.R. Botulinum neurotoxin serotypes A and B preparations have different safety margins in preclinical models of muscle weakening efficacy and systemic safety. Toxicon 2002, 40, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, K.R. A comparison of the safety margins of botulinum neurotoxin serotypes A, B, and F in mice. Toxicon 2001, 39, 1815–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutschenko, A.; Manig, A.; Reinert, M.C.; Monnich, A.; Liebetanz, D. In-vivo comparison of the neurotoxic potencies of incobotulinumtoxinA, onabotulinumtoxinA, and abobotulinumtoxinA. Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 627, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.; Nicholson, G.; Ardila, M.C.; Satorius, A.; Broide, R.S.; Clarke, K.; Hunt, T.; Francis, J. Comparative evaluation of the potency and antigenicity of two distinct BoNT/A-derived formulations. J. Neural Transm. 2013, 120, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A.; Manca, M.; Tugnoli, V.; Alberto, L. Pharmacological differences and clinical implications of various botulinum toxin preparations: A critical appraisal. Funct. Neurol. 2018, 33, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentivoglio, A.R.; Ialongo, T.; Bove, F.; De Nigris, F.; Fasano, A. Retrospective evaluation of the dose equivalence of Botox((R)) and Dysport ((R)) in the management of blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm: A novel paradigm for a never ending story. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 33, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bihari, K. Safety, effectiveness, and duration of effect of BOTOX after switching from Dysport for blepharospasm, cervical dystonia, and hemifacial spasm dystonia, and hemifacial spasm. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2005, 21, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodel, R.C.; Kirchner, A.; Koehne-Volland, R.; Künig, G.; Ceballos-Baumann, A.; Naumann, M.; Brashear, A.; Richter, H.P.; Szucs, T.D.; Oertel, W.H. Costs of treating dystonias and hemifacial spasm with botulinum toxin A. Pharmacoeconomics 1997, 12, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollewe, K.; Mohammadi, B.; Kohler, S.; Pickenbrock, H.; Dengler, R.; Dressler, D. Blepharospasm: Long-term treatment with either Botox(R), Xeomin(R) or Dysport(R). J. Neural Transm. 2015, 122, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marion, M.H.; Sheehy, M.; Sangla, S.; Soulayrol, S. Dose standardisation of botulinum toxin. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1995, 59, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, A.; Magar, R.; Findley, L.; Larsen, J.P.; Pirtosek, Z.; Ruzicka, E.; Jech, R.; Sławek, J.; Ahmed, F. Retrospective evaluation of the dose of Dysport and BOTOX in the management of cervical dystonia and blepharospasm: The REAL DOSE study. Mov. Disord. 2005, 20, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussgens, Z.; Roggenkamper, P. Comparison of two botulinum-toxin preparations in the treatment of essential blepharospasm. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1997, 235, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, C.; Ferreira, J.J.; Simões, F.; Rosas, M.J.; Magalhães, M.; Correia, A.P.; Bastos-Lima, A.; Martins, R.; Castro-Caldas, A. DYSBOT: A single-blind, randomized parallel study to determine whether any differences can be detected in the efficacy and tolerability of two formulations of botulinum toxin type A--Dysport and Botox--assuming a ratio of 4:1. Mov. Disord. 1997, 12, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, V.P.; Ehler, E.; Zakine, B.; Maisonobe, P.; Simonetta-Moreau, M. Factors influencing response to Botulinum toxin type A in patients with idiopathic cervical dystonia: Results from an international observational study. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e000881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odergren, T.; Hjaltason, H.; Kaakkola, S.; Solders, G.; Hanko, J.; Fehling, C.; Marttila, R.J.; Lundh, H.; Gedin, S.; Westergren, I.; et al. A double blind, randomised, parallel group study to investigate the dose equivalence of Dysport and Botox in the treatment of cervical dystonia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1998, 64, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranoux, D.; Gury, C.; Fondarai, J.; Mas, J.L.; Zuber, M. Respective potencies of Botox and Dysport: A double blind, randomised, crossover study in cervical dystonia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2002, 72, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rystedt, A.; Zetterberg, L.; Burman, J.; Nyholm, D.; Johansson, A. A Comparison of Botox 100 U/mL and Dysport 100 U/mL Using Dose Conversion Ratio 1:3 and 1:1.7 in the Treatment of Cervical Dystonia: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Crossover Trial. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2015, 38, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh, P.Y.; Lison, D.F. Dose standardization of botulinum toxin. Adv. Neurol. 1998, 78, 231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.Y.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, H.T.; Chung, S.J.; Kim, J.M.; Cho, J.W.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, H.N.; You, S.; Oh, E.; et al. Dysport and Botox at a ratio of 2.5:1 units in cervical dystonia: A double-blind, randomized study. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhakta, B.B.; Cozens, J.A.; Bamford, J.M.; Chamberlain, M.A. Use of botulinum toxin in stroke patients with severe upper limb spasticity. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1996, 61, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keren-Capelovitch, T.; Jarus, T.; Fattal-Valevski, A. Upper extremity function and occupational performance in children with spastic cerebral palsy following lower extremity botulinum toxin injections. J. Child. Neurol. 2010, 25, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, L.N. Botulinum toxin. Use in the treatment of spasticity in children. Ugeskr. Laeger 2000, 162, 6557–6561. [Google Scholar]

- Bladen, J.C.; Favor, M.; Litwin, A.; Malhotra, R. Switchover study of onabotulinumtoxinA to incobotulinumtoxinA for facial dystonia. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2020, 48, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juarez, H.; Salvador, S.; Hernandez, L. Cost benefit assessment of two forms of botulinum toxin type A in different pathologies. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 70, S21. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, R.; Robertson, A.; Quinones Aguilar, S.; Tzoulis, C.; Maltman, J. Real-World Dosing of OnabotulinumtoxinA and IncobotulinumtoxinA for Cervical Dystonia and Blepharospasm: Results from TRUDOSE and TRUDOSE II. Toxins 2021, 13, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggenkamper, P.; Jost, W.H.; Bihari, K.; Comes, G.; Grafe, S.; Team, N.T.B.S. Efficacy and safety of a new Botulinum Toxin Type A free of complexing proteins in the treatment of blepharospasm. J. Neural Transm. 2006, 113, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, J.; Gourdeau, A. A direct comparison of onabotulinumtoxina (Botox) and IncobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin) in the treatment of benign essential blepharospasm: A split-face technique. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2014, 34, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benecke, R.; Jost, W.H.; Kanovsky, P.; Ruzicka, E.; Comes, G.; Grafe, S. A new botulinum toxin type A free of complexing proteins for treatment of cervical dystonia. Neurology 2005, 64, 1949–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, D.; Tacik, P.; Adib Saberi, F. Botulinum toxin therapy of cervical dystonia: Comparing onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox((R))) and incobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin ((R))). J. Neural Transm. 2014, 121, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italian Society of Pharmacology. Botulin Toxins. Available online: https://sif-website.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/document/attachment/16/sif_position_paper_tox_botulinica_mar13.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Banegas, R.A.; Farache, F.; Rancati, A.; Chain, M.; Gallagher, C.J.; Chapman, M.A.; Caulkins, C.A. The South American Glabellar Experience Study (SAGE): A multicenter retrospective analysis of real-world treatment patterns following the introduction of incobotulinumtoxinA in Argentina. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2013, 33, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, G.M. Pharmacology, Part 1: Introduction to Pharmacology and Pharmacodynamics. J. Nucl. Med. Technol. 2018, 46, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Baldwin, L.A. U-shaped dose-responses in biology, toxicology, and public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2001, 22, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foran, P.G.; Mohammed, N.; Lisk, G.O.; Nagwaney, S.; Lawrence, G.W.; Johnson, E.; Smith, L.; Aoki, K.R.; Dolly, J.O. Evaluation of the therapeutic usefulness of botulinum neurotoxin B, C1, E, and F compared with the long lasting type A. Basis for distinct durations of inhibition of exocytosis in central neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInnes, C.; Dolly, J.O. Ca2+-dependent noradrenaline release from permeabilised PC12 cells is blocked by botulinum neurotoxin A or its light chain. FEBS Lett. 1990, 261, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broide, R.S.; Rubino, J.; Nicholson, G.S.; Ardila, M.C.; Brown, M.S.; Aoki, K.R.; Francis, J. The rat Digit Abduction Score (DAS) assay: A physiological model for assessing botulinum neurotoxin-induced skeletal muscle paralysis. Toxicon 2013, 71, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, J.H.; Maas, C.; Palm, M.D.; Lain, E.; Glaser, D.A.; Bruce, S.; Yoelin, S.; Cox, S.E.; Fagien, S.; Sangha, S.; et al. Safety, Pharmacodynamic Response, and Treatment Satisfaction With OnabotulinumtoxinA 40 U, 60 U, and 80 U in Subjects With Moderate to Severe Dynamic Glabellar Lines. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2022, 42, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.H.; Eaton, L.L.; Robinson, J.; Pontius, A.; Williams, E.F., III. Does increasing the dose of abobotulinumtoxina impact the duration of effectiveness for the treatment of moderate to severe glabellar lines? J. Drugs Dermatol. 2016, 15, 1544–1549. [Google Scholar]

- Poewe, W.; Deuschl, G.; Nebe, A.; Feifel, E.; Wissel, J.; Benecke, R.; Kessler, K.R.; Ceballos-Baumann, A.O.; Ohly, A.; Oertel, W.; et al. What is the optimal dose of botulinum toxin A in the treatment of cervical dystonia? Results of a double blind, placebo controlled, dose ranging study using Dysport. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1998, 64, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerscher, M.; Fabi, S.; Fischer, T.; Gold, M.; Joseph, J.; Prager, W.; Rzany, B.; Yoelin, S.; Roll, S.; Klein, G.; et al. IncobotulinumtoxinA demonstrates safety and prolonged duration of effect in a dose-ranging study for glabellar lines. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2020, 19, 985–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, J.; Solish, N.; Humphrey, S.; Rosen, N.; Muhn, C.; Bertucci, V.; Swift, A.; Metelitsa, A.; Rubio, R.G.; Waugh, J.; et al. Injectable DaxibotulinumtoxinA for the Treatment of Glabellar Lines: A Phase 2, Randomized, Dose-Ranging, Double-Blind, Multicenter Comparison With OnabotulinumtoxinA and Placebo. Dermatol. Surg. 2017, 43, 1321–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banham, S.; Taylor, D. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics. In Seminars in Clinical Psychopharmacology, 3rd ed.; Haddad, P.M., Nutt, D.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 124–150. [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic, J.; Truong, D.; Patel, A.T.; Brashear, A.; Evatt, M.; Rubio, R.G.; Oh, C.K.; Snyder, D.; Shears, G.; Comella, C. Injectable DaxibotulinumtoxinA in Cervical Dystonia: A Phase 2 Dose-Escalation Multicenter Study. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2018, 5, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comella, C.L.; Jankovic, J.; Shannon, K.M.; Tsui, J.; Swenson, M.; Leurgans, S.; Fan, W. Comparison of botulinum toxin serotypes A and B for the treatment of cervical dystonia. Neurology 2005, 65, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, K.R.; Boyd, C.; Patel, R.K.; Bowen, B.; James, S.P.; Brin, M.F. Rapid onset of response and patient-reported outcomes after onabotulinumtoxinA treatment of moderate-to-severe glabellar lines. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2011, 10, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nestor, M.; Cohen, J.L.; Landau, M.; Hilton, S.; Nikolis, A.; Haq, S.; Viel, M.; Andriopoulos, B.; Prygova, I.; Foster, K.; et al. Onset and Duration of AbobotulinumtoxinA for Aesthetic Use in the Upper face: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2020, 13, E56–E83. [Google Scholar]

- Blitzer, A.; Binder, W.J.; Aviv, J.E.; Keen, M.S.; Brin, M.F. The management of hyperfunctional facial lines with botulinum toxin: A collaborative study of 210 injection sites in 162 patients. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1997, 123, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, T.C.; Clark, R.E., 2nd. Botulinum toxin type B (MYOBLOC) versus botulinum toxin type A (BOTOX) frontalis study: Rate of onset and radius of diffusion. Dermatol. Surg. 2003, 29, 519–522. [Google Scholar]

- Matarasso, S.L. Comparison of botulinum toxin types A and B: A bilateral and double-blind randomized evaluation in the treatment of canthal rhytides. Dermatol. Surg. 2003, 29, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, L.; Vilain, C.; Volteau, M.; Picaut, P. Safety and pharmacodynamics of a novel recombinant botulinum toxin E (rBoNT-E): Results of a phase 1 study in healthy male subjects compared with abobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport(R)). J. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 407, 116516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.E.; Cai, F.; Neale, E.A. Uptake of botulinum neurotoxin into cultured neurons. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Meng, J.; Lawrence, G.W.; Zurawski, T.H.; Sasse, A.; Bodeker, M.O.; Gilmore, M.A.; Fernández-Salas, E.; Francis, J.; Steward, L.E.; et al. Novel chimeras of botulinum neurotoxins A and E unveil contributions from the binding, translocation, and protease domains to their functional characteristics. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 16993–17002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumaran, D.; Eswaramoorthy, S.; Furey, W.; Navaza, J.; Sax, M.; Swaminathan, S. Domain organization in Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin type E is unique: Its implication in faster translocation. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 386, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, J.E.; Neale, E.A.; Oyler, G.; Adler, M. Persistence of botulinum neurotoxin action in cultured spinal cord cells. FEBS Lett. 1999, 456, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloop, R.R.; Cole, B.A.; Escutin, R.O. Human response to botulinum toxin injection: Type B compared with type A. Neurology 1997, 49, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleopra, R.; Tugnoli, V.; Rossetto, O.; De Grandis, D.; Montecucco, C. Different time courses of recovery after poisoning with botulinum neurotoxin serotypes A and E in humans. Neurosci. Lett. 1998, 256, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Salas, E.; Steward, L.E.; Ho, H.; Garay, P.E.; Sun, S.W.; Gilmore, M.A.; Ordas, J.V.; Wang, J.; Francis, J.; Aoki, K.R. Plasma membrane localization signals in the light chain of botulinum neurotoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 3208–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Salas, E.; Ho, H.; Garay, P.; Steward, L.E.; Aoki, K.R. Is the light chain subcellular localization an important factor in botulinum toxin duration of action? Mov. Disord. 2004, 19 (Suppl. S8), S23–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vagin, O.; Tokhtaeva, E.; Garay, P.E.; Souda, P.; Bassilian, S.; Whitelegge, J.P.; Lewis, R.; Sachs, G.; Wheeler, L.; Aoki, R.; et al. Recruitment of septin cytoskeletal proteins by botulinum toxin A protease determines its remarkable stability. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127, 3294–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.C.; Maditz, R.; Kuo, C.L.; Fishman, P.S.; Shoemaker, C.B.; Oyler, G.A.; Weissman, A.M. Targeting botulinum neurotoxin persistence by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16554–16559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.C.; Kotiya, A.; Kiris, E.; Yang, M.; Bavari, S.; Tessarollo, L.; Oyler, G.A.; Weissman, A.M. Deubiquitinating enzyme VCIP135 dictates the duration of botulinum neurotoxin type A intoxication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E5158–E5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, E.; Kota, K.P.; Panchal, R.G.; Bavari, S.; Kiris, E. Screening of a Focused Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway Inhibitor Library Identifies Small Molecules as Novel Modulators of Botulinum Neurotoxin Type A Toxicity. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 763950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binz, T.; Blasi, J.; Yamasaki, S.; Baumeister, A.; Link, E.; Südhof, T.; Jahn, R.; Niemann, H. Proteolysis of SNAP-25 by types E and A botulinal neurotoxins. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 1617–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, H.; Hanson, P.I.; Chapman, E.R.; Blasi, J.; Jahn, R. Poisoning by botulinum neurotoxin A does not inhibit formation or disassembly of the synaptosomal fusion complex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 212, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montecucco, C.; Schiavo, G.; Pantano, S. SNARE complexes and neuroexocytosis: How many, how close? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005, 30, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Wheeler, M.B.; Kang, Y.H.; Sheu, L.; Lukacs, G.L.; Trimble, W.S.; Gaisano, H.Y. Truncated SNAP-25 (1-197), like botulinum neurotoxin A, can inhibit insulin secretion from HIT-T15 insulinoma cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 1998, 12, 1060–1070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khounlo, R.; Kim, J.; Yin, L.; Shin, Y.K. Botulinum Toxins A and E Inflict Dynamic Destabilization on t-SNARE to Impair SNARE Assembly and Membrane Fusion. Structure 2017, 25, 1679–1686.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, J.; Ovsepian, S.V.; Wang, J.; Pickering, M.; Sasse, A.; Aoki, K.R.; Lawrence, G.W.; Dolly, J.O. Activation of TRPV1 mediates calcitonin gene-related peptide release, which excites trigeminal sensory neurons and is attenuated by a retargeted botulinum toxin with anti-nociceptive potential. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 4981–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, M.; Lowe, N.J.; Kumar, C.R.; Hamm, H.; Hyperhidrosis Clinical Investigators, G. Botulinum toxin type a is a safe and effective treatment for axillary hyperhidrosis over 16 months: A prospective study. Arch. Dermatol. 2003, 139, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, N.J.; Glaser, D.A.; Eadie, N.; Daggett, S.; Kowalski, J.W.; Lai, P.Y.; North American Botox in Primary Axillary Hyperhidrosis Clinical Study Group. Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis: A 52-week multicenter double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007, 56, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haferkamp, A.; Schurch, B.; Reitz, A.; Krengel, U.; Grosse, J.; Kramer, G.; Schumacher, S.; Bastian, P.; Büttner, R.; Müller, S.; et al. Lack of ultrastructural detrusor changes following endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin type a in overactive neurogenic bladder. Eur. Urol. 2004, 46, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paiva, A.; Meunier, F.A.; Molgo, J.; Aoki, K.R.; Dolly, J.O. Functional repair of motor endplates after botulinum neurotoxin type A poisoning: Biphasic switch of synaptic activity between nerve sprouts and their parent terminals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 3200–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swartling, C.; Naver, H.; Pihl-Lundin, I.; Hagforsen, E.; Vahlquist, A. Sweat gland morphology and periglandular innervation in essential palmar hyperhidrosis before and after treatment with intradermal botulinum toxin. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2004, 51, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, D.; Brashear, A.; Hauser, R.A.; Li, H.I.; Boo, L.M.; Brin, M.F.; Group, C.D.S. Efficacy, tolerability, and immunogenicity of onabotulinumtoxina in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial for cervical dystonia. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2012, 35, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, D. Randomized controlled trial of botulinum type A toxin complex (Dysport®) for the treatment of benign essential blepharospasm. In Proceedings of the XVIIIth World Congress of Neurology, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 5–11 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bhidayasiri, R. Treatment of complex cervical dystonia with botulinum toxin: Involvement of deep-cervical muscles may contribute to suboptimal responses. Park. Relat. Disord. 2011, 17 (Suppl. S1), S20–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marion, M.H.; Hicklin, L.A. Botulinum toxin treatment of dystonic anterocollis: What to inject. Park. Relat. Disord. 2021, 88, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comella, C.L.; Jankovic, J.; Truong, D.D.; Hanschmann, A.; Grafe, S. Efficacy and safety of incobotulinumtoxinA (NT 201, XEOMIN(R), botulinum neurotoxin type A, without accessory proteins) in patients with cervical dystonia. J. Neurol. Sci. 2011, 308, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, W.A.; Monroe, D.M.; Brin, M.F.; Gallagher, C.J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the duration of clinical effect of onabotulinumtoxinA in cervical dystonia. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohart, Z.; Dashtipour, K.; Kim, H.; Schwartz, M.; Zuzek, A.; Singh, R.; Nelson, M. Real-world differences in dosing and clinical utilization of OnabotulinumtoxinA and AbobotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of upper limb spasticity. Toxicon 2024, 241, 107678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquenazi, A.; Ayyoub, Z.; Verduzco-Gutierrez, M.; Maisonobe, P.; Otto, J.; Patel, A.T. AbobotulinumtoxinA Versus OnabotulinumtoxinA in Adults with Upper Limb Spasticity: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Crossover Study Protocol. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 5623–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polacco, M.A.; Singleton, A.E.; Barnes, C.H.; Maas, C.; Maas, C.S. A Double-Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial to Determine Effects of Increasing Doses and Dose-Response Relationship of IncobotulinumtoxinA in the Treatment of Glabellar Rhytids. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2020, 41, NP500–NP511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, S.E.; Joseph, J.H.; Fagien, S.; Glaser, D.A.; Bruce, S.; Lain, E.; Yoelin, S.; Palm, M.; Maas, C.S.; Lei, X.; et al. Safety, pharmacodynamic response, and treatment satisfaction with onabotulinumtoxinA 40 U, 60 U, and 80 U in subjects with moderate to severe dynamic glabellar lines. In Proceedings of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery (ASDS) 2020 Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 9–11 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gracies, J.-M.; Brashear, A.; Jech, R.; McAllister, P.; Banach, M.; Valkovic, P.; Walker, H.; Marciniak, C.; Deltombe, T.; Skoromets, A.; et al. Safety and efficacy of abobotulinumtoxinA for hemiparesis in adults with upper limb spasticity after stroke or traumatic brain injury: A double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.T.; Munin, M.C.; Ayyoub, Z.; Francisco, G.E.; Gross, T.M.; Rubio, R.G.; Kessiak, J.P. DaxibotulinumtoxinA for injection in adults with upper limb spasticity after stroke or traumatic brain injury: A randomized placebo-controlled study (JUNIPER). In Proceedings of the International Congress of Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders, Madrid, Spain, 15–18 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Keen, M.; Blitzer, A.; Aviv, J.; Binder, W.; Prystowsky, J.; Smith, H.; Brin, M. Botulinum toxin A for hyperkinetic facial lines: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1994, 94, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elovic, E.P.; Munin, M.C.; Kanovsky, P.; Hanschmann, A.; Hiersemenzel, R.; Marciniak, C. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of incobotulinumtoxina for upper-limb post-stroke spasticity. Muscle Nerve 2016, 53, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, R.; Kim, H.; Meilahn, J.; Chambers, H.G.; Racette, B.A.; Bonikowski, M.; Park, E.S.; McCusker, E.; Liu, C.; Brin, M.F. Efficacy and safety of onabotulinumtoxinA with standardized physiotherapy for the treatment of pediatric lower limb spasticity: A randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trial. NeuroRehabilitation 2022, 50, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brashear, A.; Gordon, M.F.; Elovic, E.; Kassicieh, V.D.; Marciniak, C.; Do, M.; Lee, C.-H.; Jenkins, S.; Turkel, C. Intramuscular injection of botulinum toxin for the treatment of wrist and finger spasticity after a stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, J.D.; Fagien, S.; Joseph, J.H.; Humphrey, S.D.; Biesman, B.S.; Gallagher, C.J.; Liu, Y.; Rubio, R.G. DaxibotulinumtoxinA for Injection for the Treatment of Glabellar Lines: Results from Each of Two Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Studies (SAKURA 1 and SAKURA 2). Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2020, 145, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snapinn, S.M. Noninferiority trials. Trials 2000, 1, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattler, G.; Callander, M.J.; Grablowitz, D.; Walker, T.; Bee, E.K.; Rzany, B.; Flynn, T.C.; Carruthers, A. Noninferiority of incobotulinumtoxinA, free from complexing proteins, compared with another botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of glabellar frown lines. Dermatol. Surg. 2010, 36 (Suppl. S4), 2146–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frevert, J. Content of botulinum neurotoxin in Botox(R)/Vistabel(R), Dysport(R)/Azzalure(R), and Xeomin(R)/Bocouture(R). Drugs R&D 2010, 10, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Castaneda, J.; Jankovic, J.; Comella, C.; Dashtipour, K.; Fernandez, H.H.; Mari, Z. Diffusion, spread, and migration of botulinum toxin. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 1775–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comella, C.L.; Tanner, C.M.; DeFoor-Hill, L.; Smith, C. Dysphagia after botulinum toxin injections for spasmodic torticollis: Clinical and radiologic findings. Neurology 1992, 42, 1307–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennelly, M.; Cruz, F.; Herschorn, S.; Abrams, P.; Onem, K.; Solomonov, V.K.; Coz, E.d.R.F.; Manu-Marin, A.; Giannantoni, A.; Thompson, C.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of AbobotulinumtoxinA in Patients with Neurogenic Detrusor Overactivity Incontinence Performing Regular Clean Intermittent Catheterization: Pooled Results from Two Phase 3 Randomized Studies (CONTENT1 and CONTENT2). Eur. Urol. 2022, 82, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, F.; Herschorn, S.; Aliotta, P.; Brin, M.; Thompson, C.; Lam, W.; Daniell, G.; Heesakkers, J.; Haag-Molkenteller, C. Efficacy and safety of onabotulinumtoxinA in patients with urinary incontinence due to neurogenic detrusor overactivity: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur. Urol. 2011, 60, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg, D.; Gousse, A.; Keppenne, V.; Sievert, K.-D.; Thompson, C.; Lam, W.; Brin, M.F.; Jenkins, B.; Haag-Molkenteller, C. Phase 3 efficacy and tolerability study of onabotulinumtoxinA for urinary incontinence from neurogenic detrusor overactivity. J. Urol. 2012, 187, 2131–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellows, S.; Jankovic, J. Immunogenicity Associated with Botulinum Toxin Treatment. Toxins 2019, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dressler, D.; Bigalke, H. Immunological aspects of botulinum toxin therapy. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2017, 17, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbri, M.; Leodori, G.; Fernandes, R.M.; Bhidayasiri, R.; Marti, M.J.; Colosimo, C.; Ferreira, J.J. Neutralizing Antibody and Botulinum Toxin Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Neurotox. Res. 2016, 29, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naumann, M.; Boo, L.M.; Ackerman, A.H.; Gallagher, C.J. Immunogenicity of botulinum toxins. J. Neural Transm. 2013, 120, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brin, M.F.; Comella, C.L.; Jankovic, J.; Lai, F.; Naumann, M. Long-term treatment with botulinum toxin type A in cervical dystonia has low immunogenicity by mouse protection assay. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, J.; Carruthers, J.; Naumann, M.; Ogilvie, P.; Boodhoo, T.; Attar, M.; Gupta, S.; Singh, R.; Soliman, J.; Yushmanova, I.; et al. Neutralizing Antibody Formation with OnabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX((R))) Treatment from Global Registration Studies across Multiple Indications: A Meta-Analysis. Toxins 2023, 15, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goschel, H.; Wohlfarth, K.; Frevert, J.; Dengler, R.; Bigalke, H. Botulinum A toxin therapy: Neutralizing and nonneutralizing antibodies--therapeutic consequences. Exp. Neurol. 1997, 147, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, P.A.; Jankovic, J. Mouse bioassay versus Western blot assay for botulinum toxin antibodies: Correlation with clinical response. Neurology 1998, 50, 1624–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, P.; Fahn, S.; Diamond, B. Development of resistance to botulinum toxin type A in patients with torticollis. Mov. Disord. 1994, 9, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankovic, J.; Schwartz, K. Response and immunoresistance to botulinum toxin injections. Neurology 1995, 45, 1743–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, P.; Jansen, A.; Lee, J.-I.; Moll, M.; Ringelstein, M.; Rosenthal, D.; Bigalke, H.; Aktas, O.; Hartung, H.-P.; Hefter, H. High prevalence of neutralizing antibodies after long-term botulinum neurotoxin therapy. Neurology 2019, 92, e48–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, U.; Mühlenhoff, C.; Benecke, R.; Dressler, D.; Mix, E.; Alt, J.; Wittstock, M.; Dudesek, A.; Storch, A.; Kamm, C. Frequency and risk factors of antibody-induced secondary failure of botulinum neurotoxin therapy. Neurology 2020, 94, e2109–e2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hefter, H.; Ürer, B.; Brauns, R.; Rosenthal, D.; Meuth, S.G.; Lee, J.-I.; Albrecht, P.; Samadzadeh, S. Significant Long-Lasting Improvement after Switch to Incobotulinum Toxin in Cervical Dystonia Patients with Secondary Treatment Failure. Toxins 2022, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinnah, H.A.; Goodmann, E.; Rosen, A.R.; Evatt, M.; Freeman, A.; Factor, S. Botulinum toxin treatment failures in cervical dystonia: Causes, management, and outcomes. J. Neurol. 2016, 263, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, H.; Osei-Poku, F.; Ashton, D.; Lally, R.; Jesuthasan, A.; Latorre, A.; Bhatia, K.P.; Alty, J.E.; Kobylecki, C. Management of Secondary Poor Response to Botulinum Toxin in Cervical Dystonia: A Multicenter Audit. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2021, 8, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, N.I.; Vuong, K.D.; Jankovic, J. Long-term botulinum toxin efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity. Mov. Disord. 2005, 20, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naumann, M.; Carruthers, A.; Carruthers, J.; Aurora, S.K.; Zafonte, R.; Abu-Shakra, S.; Boodhoo, T.; Miller-Messana, M.A.; Demos, G.; James, L.; et al. Meta-analysis of neutralizing antibody conversion with onabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX(R)) across multiple indications. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 2211–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnapongse, R.B.; Lew, M.F.; Ferreira, J.J.; Gullo, K.L.; Nemeth, P.R.; Zhang, Y. Immunogenicity and long-term efficacy of botulinum toxin type B in the treatment of cervical dystonia: Report of 4 prospective, multicenter trials. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2012, 35, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankhla, C.; Jankovic, J.; Duane, D. Variability of the immunologic and clinical response in dystonic patients immunoresistant to botulinum toxin injections. Mov. Disord. 1998, 13, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samadzadeh, S.; Urer, B.; Brauns, R.; Rosenthal, D.; Lee, J.I.; Albrecht, P.; Hefter, H. Clinical Implications of Difference in Antigenicity of Different Botulinum Neurotoxin Type A Preparations: Clinical Take-Home Messages from Our Research Pool and Literature. Toxins 2020, 12, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Information for Healthcare Professionals: OnabotulinumtoxinA (Marketed as Botox/Botox Cosmetic), AbobotulinumtoxinA (Marketed as Dysport) and RimabotulinumtoxinB (Marketed as Myobloc). Available online: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170112032330/http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/drugsafetyinformationforheathcareprofessionals/ucm174949.htm (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- FDA. FDA Give Update on Botulinum Toxin Safety Warnings. Established Names of Drugs Changed. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20150106101325/http://www.fda.gov:80/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm175013.htm (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Coleman, C.; Salam, T.; Duhig, A.; Patel, A.A.; Cameron, A.; Voelker, J.; Bookhart, B. Impact of non-medical switching of prescription medications on health outcomes: An e-survey of high-volume Medicare and Medicaid physician providers. J. Mark. Access Health Policy 2020, 8, 1829883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indication | Author/Publication | RatioI (ona-botA:abobotA) |

|---|---|---|

| Blepharospasm | Bentivoglio et al., 2012 [115] | 1:1.2–1:13.3 |

| Bihari, 2005 [116] | 1:4–1:5 | |

| Dodel et al., 1997 [117] | 1:4–1:6 | |

| Kollewe et al., 2015 [118] | 1:2.3 | |

| Marion et al., 1995 [119] | 1:3 | |

| Marchetti et al., 2005 [120] | 1:3–1:11 | |

| Nussgens and Roggenkämper, 1997 [121] | 1:4 | |

| Sampaio et al., 1997 [122] | 1:4 | |

| Cervical dystonia | Bihari, 2005 [116] | 1:4–1:5 |

| Dodel et al., 1997 [117] | 1:4–1.6 | |

| Marchetti et al., 2005 [120] | 1:3–1:11 | |

| Misra et al., 2012 [123] | 3.1:1 | |

| Odergren et al., 1998 [124] | 1:3 | |

| Ranoux D et al., 2002 [125] | 1:3–1:4 | |

| Rystedt A et al., 2015 [126] | 1.7:1 | |

| Van den Bergh and Lison, 1998 [127] | 1:2.5 | |

| Yun et al., 2015 [128] | 1:2.5 | |

| Hemifacial spasm | Bihari, 2005 [116] | 1:4–1:5 |

| Dodel et al., 1997 [117] | 1:4–1:6 | |

| Marion et al., 1995 [119] | 1:3 | |

| Van den Bergh and Lison, 1998 [127] | 1:2.5 | |

| Spasticity | Bhakta et al., 1996 [129] | 1:4–1:5 |

| Keren-Capelovitch et al., 2010 [130] | 1:2.5 | |

| Rasmussen et al., 2000 [131] | 1:4 |

| Indication | Author/Publication | Ratio (onabotA:incobotA) |

|---|---|---|

| Blepharospasm | Bladen et al., 2020 [132] | 1:1 |

| Juarez et al., 2011 [133] | 1:1.2 | |

| Kent et al., 2021 [134] | 1:1.37 | |

| Kollewe et al., 2015 [118] | 1:1.2 | |

| Roggenkämper et al., 2006 [135] | 1:1 | |

| Saad and Gourdeau, 2014 [136] | 1:1 | |

| Cervical dystonia | Benecke et al., 2005 [137] | 1:1 |

| Dressler et al., 2014 [138] | 1:1 | |

| Juarez et al., 2011 [133] | 1:1.2 | |

| Kent et al., 2021 [134] | 1:1.21 | |

| Hemifacial spasm | Bladen et al., 2020 [132] | 1:1 |

| Juarez et al., 2011 [133] | 1:1.1 | |

| Spasticity | Italian Society of Pharmacology, 2017 [139]; Ferrari et al., 2018 [114] | 1:1.5–1:2.5 |

| Glabellar lines | Banegas et al., 2013 [140] | 1:1 |

| Blepharospasm | Kollewe et al., 2015 [118] | 1:2 |

| Intrinsic Product Factors |

|---|

| Serotype/subtype |

| Formulation |

| Unit potency |

| Peripheral neuron type |

| Motor (alpha and gamma) |

| Autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) |

| Nociceptor |

| Study-level factors |

| Patient population |

| Dose |

| Injection paradigm |

| Efficacy and duration assessments |

| Rating scales/raters |

| Follow-up timepoint frequency |

| Patient population | Are there differences in clinical presentation, severity, or duration of disease, or of pre-existing conditions/comorbidities? Is a more or less responsive group included or excluded? Disease severity/complexity may influence overall efficacy, which can influence efficacy and duration. |

| Doses | Does the study account for dose–response effects in comparing products, in addition to non-interchangeability of units when evaluating efficacy and duration? Higher doses may lead to increased efficacy and longer durations. |

| Injection paradigm | Are the muscles and injection sites optimized for each of the BoNT products? |

| Efficacy and duration assessments | Are the definitions of efficacy and duration the same/comparable for the different products? For example, a definition that requires two raters to agree on an outcome is more difficult to achieve and will lead to longer duration than that of a single rater. |

| Rating scales/raters | Are the same rating scales being used? Who is doing the rating (e.g., investigator, subject)? Different scales and raters may yield different apparent responder rates and durations. Patient perception is an important outcome. |

| Follow-up timepoints | Is the number of timepoints adequate to provide a full assessment of duration? More follow-up timepoints give a more precise estimate of duration. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brin, M.F.; Nelson, M.; Ashourian, N.; Brideau-Andersen, A.; Maltman, J. Update on Non-Interchangeability of Botulinum Neurotoxin Products. Toxins 2024, 16, 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins16060266

Brin MF, Nelson M, Ashourian N, Brideau-Andersen A, Maltman J. Update on Non-Interchangeability of Botulinum Neurotoxin Products. Toxins. 2024; 16(6):266. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins16060266

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrin, Mitchell F., Mariana Nelson, Nazanin Ashourian, Amy Brideau-Andersen, and John Maltman. 2024. "Update on Non-Interchangeability of Botulinum Neurotoxin Products" Toxins 16, no. 6: 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins16060266

APA StyleBrin, M. F., Nelson, M., Ashourian, N., Brideau-Andersen, A., & Maltman, J. (2024). Update on Non-Interchangeability of Botulinum Neurotoxin Products. Toxins, 16(6), 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins16060266