Abstract

Chronic migraine (CM) significantly affects underage individuals. The study objectives are (1) to analyze the effectiveness and safety of onabotulinumtoxinA (BTX-A) in adolescents with CM; (2) to review the literature on BTX-A use in the pediatric population. This prospective observational study included patients under 18 years old with CM treated with BTX-A (PREEMPT protocol) as compassionate use. Demographic, efficacy (monthly headache days—MHD; monthly migraine days—MMD; acute medication days/month—AMDM) and side effect data were collected. A ≥ 50% reduction in MHD was considered as a response. Effectiveness and safety were analyzed at 6 and 12 months. A systematic review of the use of BTX-A in children/adolescents was conducted in July 2023. In total, 20 patients were included (median age 15 years [14.75–17], 70% (14/20) females). The median basal frequencies were 28.8 [20–28] MHD, 18 [10–28] MMD and 10 [7.5–21.2] AMDM. Compared with baseline, at 6 months (n = 20), 11 patients (55%) were responders, with a median reduction in MHD of −20 days/month (p = 0.001). At 12 months (n = 14), eight patients (57.1%) were responders, with a median reduction in MHD of −17.5 days/month (p = 0.002). No adverse effects were reported. The literature search showed similar results. Our data supports the concept that BTX-A is effective, well tolerated, and safe in adolescents with CM resistant to oral preventatives.

Key Contribution:

Our study, along with the previous literature, supports the effectiveness, safety and tolerability of BTX-A as a therapeutic tool for adolescents with CM.

1. Introduction

Migraine is a common and disabling neurological disorder that affects all ages. In children and adolescents, the prevalence of migraine is estimated to be around 11% [1], increasing from childhood to adolescence—from 5% among children under 10 years old to 15% among teenagers [2]—with an incidence peak occurring around the initiation of puberty, typically at the age of 13 [3]. Concerning chronic migraine (CM), it is reported to affect from 0.2% to 12% of children/adolescents [1]. Often, anxiety, depression, or other psychological factors are associated with it, and it is not uncommon to encounter young patients with daily headache [4,5,6,7]. In addition, according to the Global Burden of Disease study, headache is ranked as the second most disabling disease worldwide among individuals between 10 and 24 years old [8].

While the overall burden of migraine is acknowledged to be substantial in the overall population [8], children/adolescents have to face further major issues: (1) no preventive treatment is specifically approved in this age group for migraine, whose pharmacological management is therefore only based on recommendations and is therapeutically limited [9]; (2) inadequate disease management during early stages affects social and educational domains with a severe impact later on in life (e.g., career development) [10].

OnabotulinumtoxinA (BTX-A) has demonstrated its efficacy and safety in randomized controlled trials (PREEMPT trials 1, 2) [11,12] and in the real world for CM prevention in adults [13,14,15] and could potentially be a therapeutic tool for children/adolescents, especially for cases that are more treatment resistant, yet data on its use in this specific population are scarce [16,17].

Thus, we aimed to (1) analyze the effectiveness and safety profile of BTX-A in our real-world cohort of underage migraine patients and (2) review the current evidence on the use of BTX-A in children/adolescents with CM.

2. Results

2.1. Case Series

2.1.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 20 patients met the inclusion criteria. Of those, 14 patients were female (70%), with a median age of 15 years old [IQR 14.75–17]. Relevant comorbidities included obesity (1/20; 5%), anxiety (2/20; 10%) and depression (3/20; 15%). Patients had a median age of migraine onset of 12 years [IQR 8–14] and a median age of migraine chronification of 14 [IQR 12.5–15.5]. At baseline, the median monthly headache days (MHD) was 28 days/month [IQR 20–28], the median monthly migraine days (MMD) was 18 days/month [IQR 10–28] and the median of acute medications days/month (AMDM) was 10 days/month [IQR 7.5–21.2]. The median number of failed previous preventive treatments was one, with 20% of patients (4/20) with stable concomitant oral preventive medications. All baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basal characteristics and demographics.

2.1.2. Effectiveness

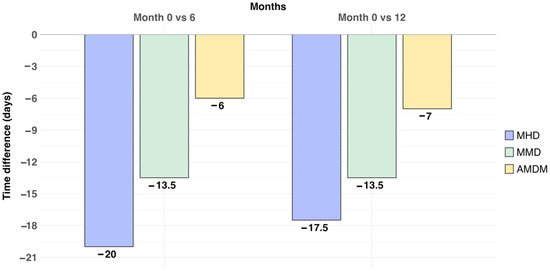

At 6 months (after 2 BTX-A doses), the median reduction in MHD was −20 days/month (M0 median 28 days/month [IQR 20–28], M6 median 8 days/month [5.5–26.5] (p = 0.001)), the median reduction in MMD was −13.5 days/month (M0 median 18 days/month [10.0–28.0], M6 median 4.5 days/month [2.8–7.0] (p < 0.001)), and in AMDM, it was −6 days/month (M0 median 10 days/month [7.5–21.2], M0 median 4 days/month [2.5–7.5] (p = 0.01)). Eleven out of twenty patients were responders (55%).

At 12 months, there was a significant reduction in MHD (−17.5 days/month, M12 median 10.5 days/month [5.2–21.5]; p = 0.002), MMD (−13.5 days/month, M12 median 4.5 [2.8–7.8] p = 0.014) and in AMDM (−7 days/month; M12 median 3 days/month [2.0–6.0]; p = 0.028). Eight out of fourteen patients were responders (57.1%). Figure 1 shows changes in headache frequencies across the study period.

Figure 1.

Median reduction in headache frequencies across the study period (baseline 0–month, 6–month and 12–month follow-up). The median reduction in MHD, MMD and AMDM is represented in days/month. MHD: monthly headache days; MMD: monthly migraine days; AMDM: acute medication days/month.

Furthermore, although in our study no direct comparison between 6 months and 12 months of treatment has been performed, the results show a tendency toward a maintained BTX-A response.

2.1.3. Safety

BTX-A treatment was well tolerated, with no minor or major adverse events reported. None of the patients discontinued treatment due to side effects.

2.2. Narrative Review

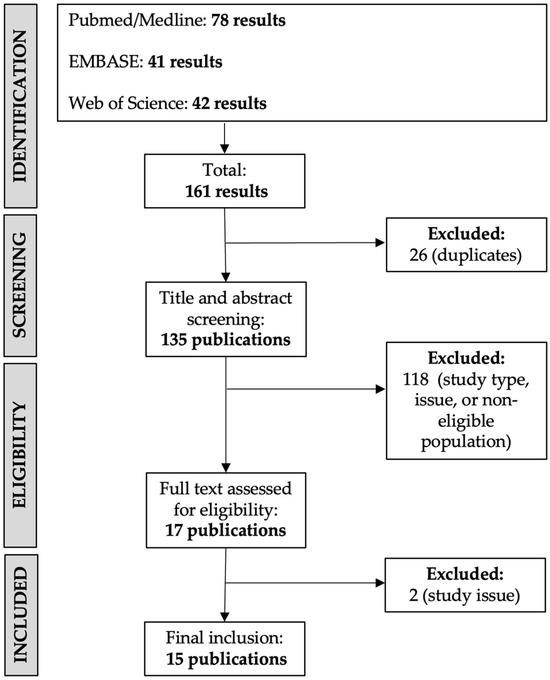

The PRISMA guideline-based search process is summarized in Figure 2. A total of 160 results were screened, and a subset of 15 publications were ultimately included. Published studies have focused on the efficacy of BTX-A treatment as well as on describing treatment safety and tolerability (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of study selection for review.

Table 2.

Narrative review of the use of BTX-A in children and adolescents with migraine.

Since the first published studies in 2009, only two randomized control trials (RCTs) have been published. The first one [16] was published in January 2020 and consisted of a single-treatment, multicenter, double-blind study. Treatment with BTX-A was 75 U or 155 U in 31 injection sites following the PREEMPT protocol. The three treatment arms (placebo-PBO, 75 U and 155 U BTX-A) reduced headache frequency days and severe headache days, but without significant differences between them. However, the study had two important limitations: first, there was a probable higher PBO effect than expected because of a 2:1 chance of patients receiving active treatment; and second, efficacy was evaluated after a single-dose treatment.

The second RCT [17] was published in April 2020 and used an AB|BA crossover design with two phases: two sets of treatments in a double-blind period and two additional sets of treatments in which patients could elect between BTX-A or standard care. Fifteen patients were randomized, and treatment consisted of 155 U of BTX-A in 31 injection sites following the PREEMPT protocol. Compared with patients who received PBO (6/15), 9/15 of the patients who received BTX-A presented a statistically significant reduction in headache frequency (median frequency in days of 20 ([QR 7 to 17] vs. 28 [IQR 23 to 28]; p = 0.038), intensity (median in intensity in a 0 to 10 pain numeric rating scale of 5 [IQR 3 to 7] vs. 7 [IQR 5 to 9]; p = 0.047) and in disability assessed with PedMIDAS score (median grade of 3 [IQR 2 to 4] vs. 4 [IQR 4 to 4]; p = 0.047). Interestingly, two patients who were non-responders to BTX-A were diagnosed with idiopathic intracranial hypertension, and the re-run analysis without them showed greater differences between both interventions.

Regarding the efficacy of BTX-A, with respect to headache frequency, all studies showed a reduction in MHD, yielding proportions of treatment responders (i.e., ≥50% reduction in MHD) ranging from 45% to 70% [18,19]. In terms of headache intensity, often measured with the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), a significant reduction was commonly associated with BTX-A across a substantial proportion of studies, yielding a mean VAS reduction from 1.28 to 5.2 points [17,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Concerning the duration of headache attack, there are a few controversial results regarding its improvement, with two studies favoring positive effects [17,23] and one showing no effect [16]. Moreover, one study suggests that treatment with BTX-A might contribute to reducing the occurrence of auras [25].

Furthermore, regarding the safety of BTX-A, no severe adverse events have been documented, except from a case report describing reversible, progressively decreasing pulmonary function in a 15-year-old female treated with 150 U of BTX-A. It is noteworthy that the patient had pre-existing relevant health problems consisting of a common variable immunodeficiency undergoing routine IVIG infusions and non-steroidal hypersensitivity [26]. Most of the reported side effects were mild, including injection-site erythema, edema and/or pain, pruritus, headache, eyebrow elevation, neck pain and/or weakness, dizziness and nausea, which were not described as reasons for discontinuation in any of the included studies.

Moreover, some studies have investigated the potential impact of comorbidity on the response to BTX-A, with controversial results. Goenka et al. [27] showed that anxiety (GAD-7 score greater than 15) was significantly higher among non-responders (67%) compared to responders (42%) (p = 0.040). However, Papetti et al. [18] observed no impact of anxiety (GAD-7) or depression (PHQ-9) on the BTX-A response. Additionally, a limited number of studies have investigated how BTX-A might enhance the quality of life in pediatric patients using the PedMIDAS score, also with conflicting outcomes; two studies support a significant improvement in disability [17,27] but another does not [16].

3. Discussion

Consistent with previous research, our study supports the concept that BTX-A can be an effective and safe treatment for the adolescent population with CM.

Considering headache effectiveness, nearly 60% of patients were responders at 12 months of follow-up, aligning with findings from prior investigations [16,17,18,19,21,22,30]. Both MHD and MMD were significantly reduced following treatment initiation, with a median reduction of 8 and 4.5 days per month, respectively. Furthermore, treatment with BTX-A was accompanied by a reduction in the utilization of acute headache medications, potentially mitigating the risk of medication overuse headache [31].

In addition, our study results also underscore the favorable adherence to BTX-A treatment by patients. BTX-A treatment was well tolerated, with no major adverse events observed, similar to the published studies (as detailed in our narrative review results).

Our narrative review discloses that evidence is scarce because of multiple limitations. First, there are very few studies meeting our review’s inclusion criteria (15 studies over a span of 15 years). Secondly, the quality of the studies is generally low, with only two RCTs [16,17] and most of them being retrospective case series studies.

In addition, the patient sample sizes in these studies are small, restricting the ability to draw statistically significant conclusions. Furthermore, studies use different BTX-A doses, and those conducted prior to the publication of the PREEMPT protocol did not adhere to established injection sites, making precise inter-study comparisons difficult.

Lastly, in most of the studies, the concurrent use of other preventive medications was allowed but with unclear descriptions of the types and dosages of and changes in oral medications, potentially representing confounding factors.

Concerning the limitations of our clinical study, we are aware that, like previous studies, our sample size is small; however, this is a well-phenotyped cohort relying on robust data (e.g., headache e-diaries). Also, we did not have assessed Patient Reported Outcomes Measures such as PedMIDAS, which would have been interesting to further explore patient perception and the impact on patient quality of life. Finally, no control group was included in the study. We cannot exclude, for this reason, a placebo effect, which is known to be high in the pediatric population; nevertheless, given the 12-month duration of the study and the sustained response to BTX-A, the influence of this effect may be limited.

With all this, it is essential to undertake more studies, including RCTs, to bolster the evidence supporting the use of BTX-A in adolescents.

4. Conclusions

Both the literature systematic review and our own prospective study show that BTX-A stands as an effective and safe therapeutic option for adolescents with chronic migraine. However, to firmly establish BTX-A as a standard treatment, there remains a requirement for additional high-quality empirical substantiation. Properly treating migraine in these stages of life can help teenagers perform in their academic and personal life and can control the progression of the disease in order to start adulthood with a controlled migraine disease.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Study Design, Population, and Outcomes

This is a prospective pilot study conducted in the Headache Clinic of a tertiary hospital in Spain. We included all consecutive outpatients attended between October 2019 and May 2023, meeting the following inclusion criteria: (1) age < 18 years old; (2) diagnosis of CM according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3rd Edition (ICHD-3) [32]; (3) failure with one or more migraine oral preventive treatment (including contraindication); (4) treatment with BTX-A 195 U every 3 months, according to the PREEMPT protocol [28], on compassionate use.

BTX-A was offered as compassionate use after more than 1 failure with oral preventive treatment, considering the absence of an approved oral preventive treatment for CM in the underage population, and upon patients’ and legal tutors’ approvals.

Concomitant oral preventive treatments were allowed, provided that their doses were stable during the study period (at least 1 month before starting BTX-A), in patients who wished to continue treatment despite limited efficacy (defined as a reduction ≤ 50% in MHD). We included patients with daily headache.

BTX-A was administered to all patients according to the PREEMPT injection paradigm [30], using a total dose of 195 units (U) injected in 39 sites (frontalis 20 U in 4 sites; corrugator 10 U in 2 sites; procerus 5 U in 1 site; occipitalis 40 U in 8 sites; temporalis 50 U in 10 sites; trapezius 50 U in 10 sites; cervical paraspinal muscle group 20 U in 4 sites) every 12 weeks.

We collected demographic data (age, sex) and comorbidities (including anxiety, depression, obesity, cardiovascular disease, neurovascular disease). Additional data included migraine onset and age of diagnosis (years), the presence of aura and other migraine characteristics. Through electronic headache diaries (e-diaries) we collected MHD, MMD and AMDM values. We evaluated presence of any adverse event. At least three visits were stablished, including baseline (M0), 6-month (M6) and 12-month (M12) follow-ups.

The primary outcome of this study was to assess the effectiveness of BTX-A in terms of reduction in MHD at 6 months. Secondary outcomes were reduction in MHD at 12 months, reduction in MMD and AMDM at 6 and 12 months and the proportion of responders at 6 and 12 months. We defined response to BTX-A as ≥50% reduction in MHD. We evaluated BTX-A safety, reason for discontinuation and retention rate.

5.2. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using R version 4.3.1 (2023-06-16).

Sex, aura and all comorbidities were processed as categorical variables described with frequency and percentage, while age, evolution, MHD, MMD and AMDM were processed as quantitative variables described with median and quantiles.

According to the Shapiro test results assessing the normality of data, a paired t-test (normally distributed data) or Wilcoxon test (not-normally distributed data) was used to study differences in frequencies and medication at months 0–6 and 0–12. There was no need to adjust the p-value, as this was an exploratory study.

A statistical power calculation prior to the study was not conducted because the sample size was based on the available data. No missing values were obtained. We considered two-tailed test p values < 0.05 statistically significant.

5.3. Narrative Review: Search Strategy and Study Selection

A literature search was conducted in July 2023 using the following electronic databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE and Web of Science. Separate searches were performed within each database (the search term strategy is described in Supplementary Material S1). Eligibility criteria were established before the literature search was conducted. Studies involving patients under the age of 18 years and in English were included. Reviews, expert opinions, practice guidelines, book chapters and abstracts or congress posters were also excluded.

Using the aforementioned criteria, E.C. and L.G.-D. independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all resulting publications. Studies that met the exclusion criteria and duplicates were removed. Full texts of the remaining papers were then analyzed. For the risk of bias assessment, Cochrane Collaboration’s tool was used for randomized clinical trials (RCTs) [33] and the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Exposures (ROBINS-E Version 20) was used for observational epidemiologic studies [34].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/toxins16050221/s1, Supplementary Material S1. Search term strategy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C. and P.P.-R.; methodology, L.G.-D., E.C., R.M.-d.-l.-V. and V.J.G.; software, L.G.-D. and E.C.; validation, L.G.-D. and E.C.; formal analysis, L.G.-D., E.C., R.M.-d.-l.-V. and V.J.G.; investigation, L.G.-D., E.C., R.M.-d.-l.-V. and V.J.G.; resources, L.G.-D. and E.C.; data curation, L.G.-D. and E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G.-D. and E.C.; writing—review and editing, A.A., M.T.-F., R.M.-d.-l.-V.,V.J.G. and P.P.-R.; visualization, L.G.-D., E.C. and P.P.-R.; supervision, E.C. and P.P.-R.; project administration E.C. and P.P.-R.; L.G.-D. and E.C. contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee (PR(AG)53/2017, approval date 02-02-2022). All patients gave informed consent for the analysis of anonymous patients’ data.

Informed Consent Statement

All patients and their legal tutors consented to the publication of anonymous individual data.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available, and any anonymized data will be shared upon request from any qualified investigator.

Acknowledgments

Miriam Basagaña Farrés (Biblioteca Vall d’Hebron) for contributing to the literature search and search term strategy in the three electronic databases.

Conflicts of Interest

L.G.-D. reports no disclosures. E.C. has received honoraria from Novartis, Chiesi, Lundbeck, MedScape; his salary has been partially funded by Río Hortega grant Acción Estratégica en Salud 2017–2020, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CM20/00217). He is a junior editor for Cephalalgia. R.M.-d.-l.-V. reports no disclosures. V.J.G. reports no disclosures. A.A. has received honoraria from Allergan-AbbVie, Novartis, Chiesi. M.T.-F. has received honoraria from Allergan-AbbVie, Novartis, Chiesi and Teva. P.P.-R. has received, in the last three years, honoraria as a consultant and speaker for: AbbVie, Biohaven, Chiesi, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Medscape, Novartis, Pfizer and Teva. Her research group has received research grants from AbbVie, Novartis and Teva; as well as, Instituto Salud Carlos III, EraNet Neuron, European Regional Development Fund (001-P-001682) under the framework of the FEDER Operative Programme for Catalunya 2014-2020-RIS3CAT; has received funding for clinical trials from AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Teva. She is the Honorary Secretary of the International Headache Society. She is in the editorial board of Revista de Neurologia. She is an associate editor for Cephalalgia, Headache, Neurologia, The Journal of Headache and Pain and Frontiers of Neurology. She is a member of the Clinical Trials Guidelines Committee of the International Headache Society. She has edited the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Headache of the Spanish Neurological Society. P.P.-R does not own stocks from any pharmaceutical company.

Abbreviations

| AMDM | Acute medication days/month |

| BAI | Beck Anxiety Inventory Scale |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| BTX-A | OnabotulinumtoxinA |

| CM | Chronic migraine |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| ICHD-3 | International Classification of Headache Disorders |

| MHD | Monthly headache days |

| MMD | Monthly migraine days |

| RCT | Randomized clinical trial |

| PBO | Placebo |

| U | Unit |

References

- Onofri, A.; Pensato, U.; Rosignoli, C.; Wells-Gatnik, W.; Stanyer, E.; Ornello, R.; Chen, H.Z.; De Santis, F.; Torrente, A.; Mikulenka, P.; et al. European Headache Federation School of Advanced Studies (EHF-SAS). Primary headache epidemiology in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Headache Pain. 2023, 24, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, T.W.; Hu, X.; Campbell, J.C.; Buse, D.C.; Lipton, R.B. Migraine prevalence by age and sex in the United States: A life-span study. Cephalalgia 2010, 30, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alashqar, A.; Shuaibi, S.; Ahmed, S.F.; AlThufairi, H.; Owayed, S.; AlHamdan, F.; Alroughani, R.; Al-Hashel, J.Y. Impact of Puberty in Girls on Prevalence of Primary Headache Disorder Among Female Schoolchildren in Kuwait. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Ferus, M.; Vila-Sala, C.; Quintana, M.; Ajanovic, S.; Gallardo, V.J.; Gomez, J.B.; Alvarez-Sabin, J.; Macaya, A.; Pozo-Rosich, P. Headache, comorbidities and lifestyle in an adolescent population (The TEENs Study). Cephalalgia 2019, 39, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, H.; Tokunaga, S.; Taniguchi, N.; Inoue, K.; Okuda, M.; Kato, T.; Takeshima, Y. Emotional and behavioral problems in pediatric patients with migraine and tension-type headache. Brain Dev. 2021, 43, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommer, R.; Lateef, T.; He, J.P.; Merikangas, K. Headache and mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of American youth. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bektaş, Ö.; Uğur, C.; Gençtürk, Z.B.; Aysev, A.; Sireli, Ö.; Deda, G. Relationship of childhood headaches with preferences in leisure time activities, depression, anxiety and eating habits: A population-based, cross-sectional study. Cephalalgia 2015, 35, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskoui, M.; Pringsheim, T.; Billinghurst, L.; Potrebic, S.; Gersz, E.M.; Gloss, D.; Holler-Managan, Y.; Leininger, E.; Licking, N.; Mack, K.; et al. Practice guideline update summary: Pharmacologic treatment for pediatric migraine prevention: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology 2019, 93, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonaci, F.; Voiticovschi-Iosob, C.; Di Stefano, A.L.; Galli, F.; Ozge, A.; Balottin, U. The evolution of headache from childhood to adulthood: A review of the literature. J. Headache Pain. 2014, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurora, S.K.; Dodick, D.W.; Turkel, C.C.; DeGryse, R.E.; Silberstein, S.D.; Lipton, R.B.; Diener, H.C.; Brin, M.F. PREEMPT 1 Chronic Migraine Study Group. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: Results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 1 trial. Cephalalgia 2010, 30, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, H.C.; Dodick, D.W.; Aurora, S.K.; Turkel, C.C.; DeGryse, R.E.; Lipton, R.B.; Silberstein, S.D.; Brin, M.F.; PREEMPT 2 Chronic Migraine Study Group. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: Results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial. Cephalalgia 2010, 30, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanteri-Minet, M.; Ducros, A.; Francois, C.; Olewinska, E.; Nikodem, M.; Dupont-Benjamin, L. Effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX®) for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine: A meta-analysis on 10 years of real-world data. Cephalalgia 2022, 42, 1543–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothrock, J.F.; Adams, A.M.; Lipton, R.B.; Silberstein, S.D.; Jo, E.; Zhao, X.; Blumenfeld, A.M.; on behalf of the FORWARD Study investigative group. FORWARD Study: Evaluating the Comparative Effectiveness of Onabotulinumtoxina and Topiramate for Headache Prevention in Adults With Chronic Migraine. Headache 2019, 59, 1700–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenfeld, A.M.; Stark, R.J.; Freeman, M.C.; Orejudos, A.; Manack Adams, A. Long-term study of the efficacy and safety of OnabotulinumtoxinA for the prevention of chronic migraine: COMPEL study. J. Headache Pain. 2018, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winner, P.K.; Kabbouche, M.; Yonker, M.; Wangsadipura, V.; Lum, A.; Brin, M.F. A Randomized Trial to Evaluate OnabotulinumtoxinA for Prevention of Headaches in Adolescents With Chronic Migraine. Headache 2020, 60, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.; Calderon, M.D.; Crain, N.; Pham, J.; Rinehart, J. Effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX) in pediatric patients experiencing migraines: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover study in the pediatric pain population. Reg. Anesth. Pain. Med. 2021, 46, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papetti, L.; Frattale, I.; Ursitti, F.; Sforza, G.; Monte, G.; Ferilli, M.A.N.; Tarantino, S.; Proietti Checchi, M.; Valeriani, M. Real Life Data on OnabotulinumtoxinA for Treatment of Chronic Migraine in Pediatric Age. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goenka, A.; Yu, S.G.; George, M.C.; Chikkannaiah, M.; MacDonald, S.; Stolfi, A.; Kumar, G. Is Botox Right for Me: When to Assess the Efficacy of the Botox Injection for Chronic Migraine in Pediatric Population. Neuropediatrics 2022, 53, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karian, V.; Morton, H.; Schefter, Z.J.; Smith, A.; Rogan, H.; Morse, B.; LeBel, A. OnabotulinumtoxinA for Pediatric Migraine. Pain. Manag. Nurs. 2023, 24, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A.S.; Huss, K.; Blaschek, A.; Koerte, I.K.; Zeycan, B.; Roser, T.; Langhagen, T.; Schwerin, A.; Berweck, S.; Reilich, P.; et al. Ten-year follow-up in a case series of integrative botulinum toxin intervention in adolescents with chronic daily headache and associated muscle pain. Neuropediatrics 2012, 43, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, L.; Liu, C. Experience of Botulinum Toxin A Injections for Chronic Migraine Headaches in a Pediatric Chronic Pain Clinic. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 26, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.; Calderon, M.D.; Wu WDer Grant, J.; Rinehart, J. Onabotulinumtoxin A (BOTOX®) for ProphylaCTIC Treatment of Pediatric Migraine: A Retrospective Longitudinal Analysis. J. Child. Neurol. 2018, 33, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.S.; Bragin, I.; Rende, E.; Mejico, L.; Werner, K.E. Further Evidence that Onabotulinum Toxin is a Viable Treatment Option for Pediatric Chronic Migraine Patients. Cureus 2019, 11, e4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.Y.; Garza, I.; Dodick, D.W.; Robertson, C.E. The Effect of OnabotulinumtoxinA on Aura Frequency and Severity in Patients With Hemiplegic Migraine: Case Series of 11 Patients. Headache 2018, 58, 973–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, J.D.; Boesch, R.P.; Mack, K.J. Decreased Pulmonary Function During Botulinum Toxin A Therapy for Chronic Migraines in a 17-Year-Old Female. Headache 2018, 58, 1259–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goenka, A.; Yu, S.G.; Chikkannaiah, M.; George, M.C.; MacDonald, S.; Stolfi, A.; Kumar, G. Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Predictor for Poor Responsiveness to Botulinum Toxin Type A Therapy for Pediatric Migraine. Pediatr. Neurol. 2022, 130, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, K.; Oas, K.H.; Mack, K.J.; Garza, I. Experience with botulinum toxin type A in medically intractable pediatric chronic daily headache. Pediatr. Neurol. 2010, 43, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, V.W.; Mccabe, E.J.; Macgregor, D.L. Botox treatment for migraine and chronic daily headache in adolescents. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2009, 41, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenfeld, A.; Silberstein, S.D.; Dodick, D.W.; Aurora, S.K.; Turkel, C.C.; Binder, W.J. Method of injection of onabotulinumtoxinA for chronic migraine: A safe, well-tolerated, and effective treatment paradigm based on the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache 2010, 50, 1406–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashina, S.; Terwindt, G.M.; Steiner, T.J.; Lee, M.J.; Porreca, F.; Tassorelli, C.; Schwedt, T.J.; Jensen, R.H.; Diener, H.C.; Lipton, R.B. Medication overuse headache. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, J. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bero, L.; Chartres, N.; Diong, J.; Fabbri, A.; Ghersi, D.; Lam, J.; Lau, A.; McDonald, S.; Mintzes, B.; Sutton, P.; et al. The risk of bias in observational studies of exposures (ROBINS-E) tool: Concerns arising from application to observational studies of exposures. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).