Dietary Protein Consumption and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

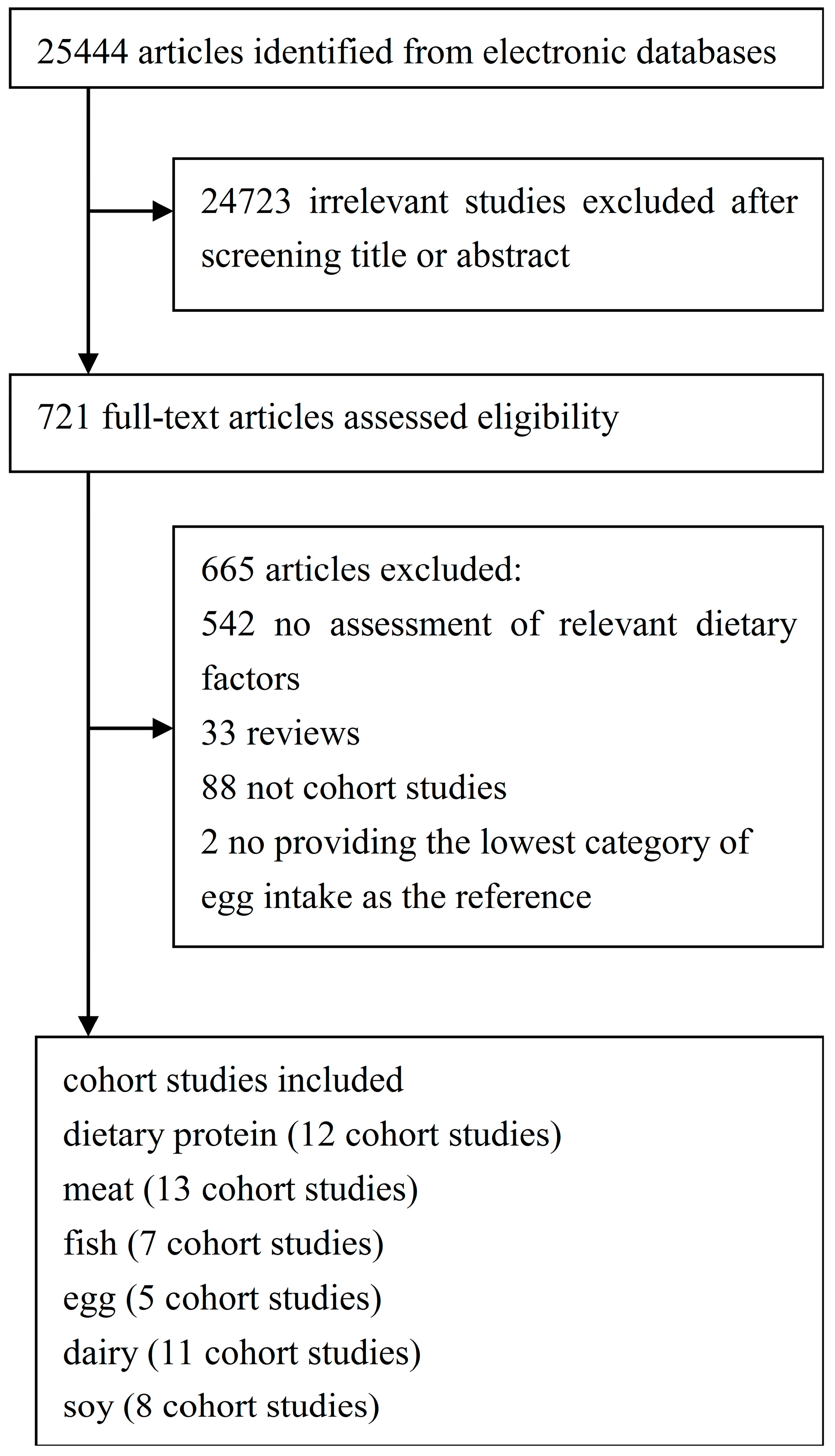

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

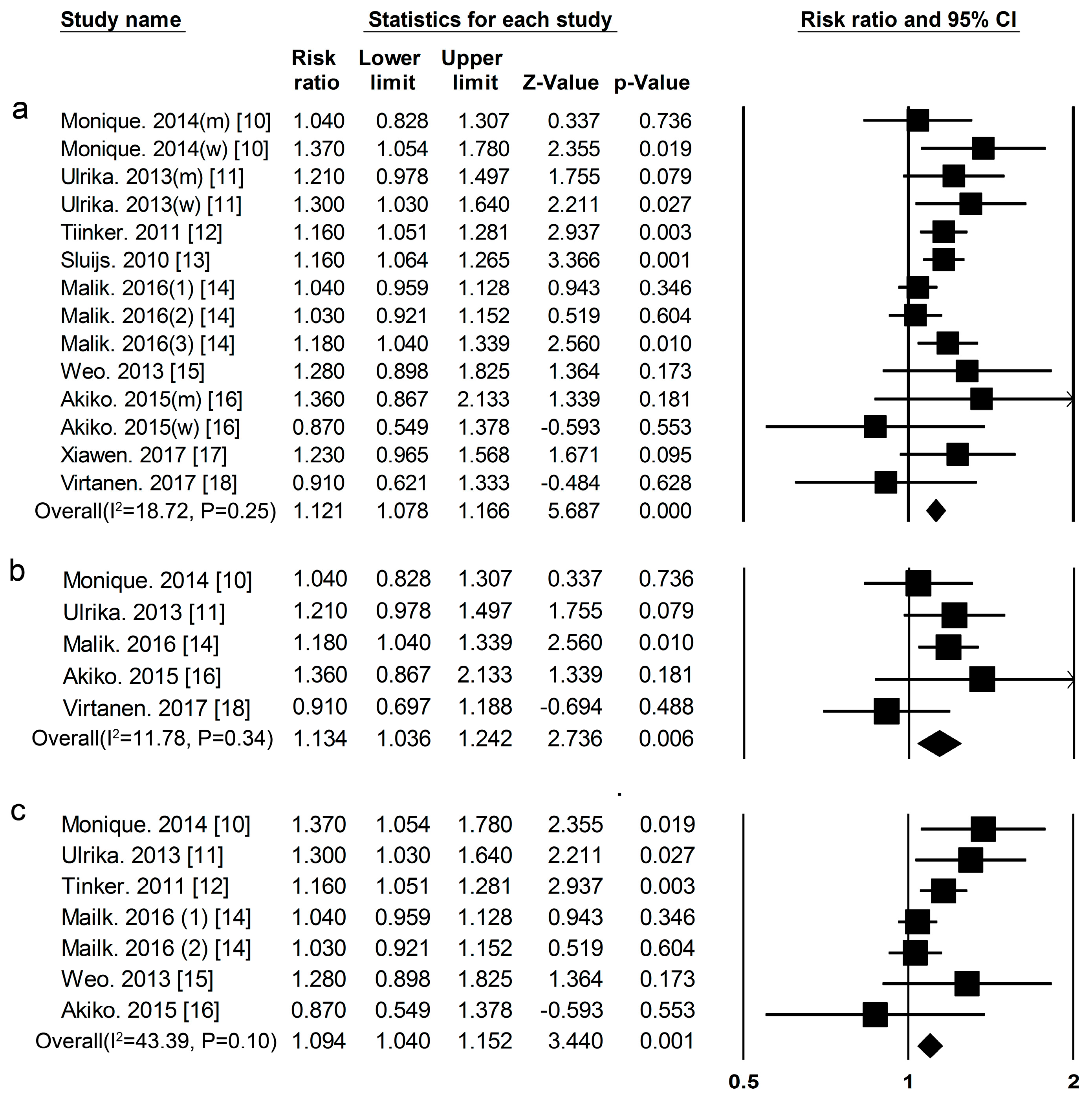

3.1. Dietary Protein Intake and Risk of T2DM

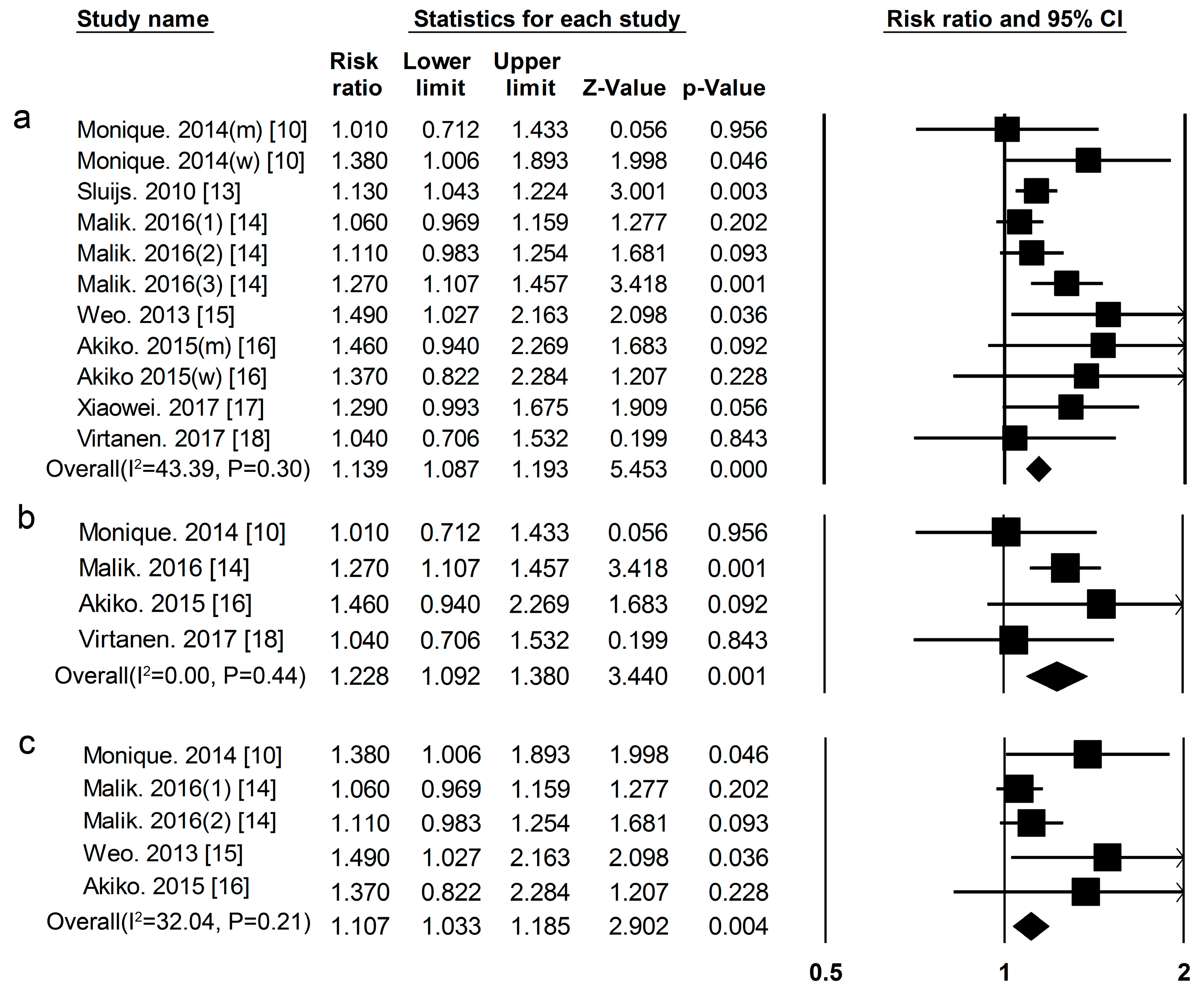

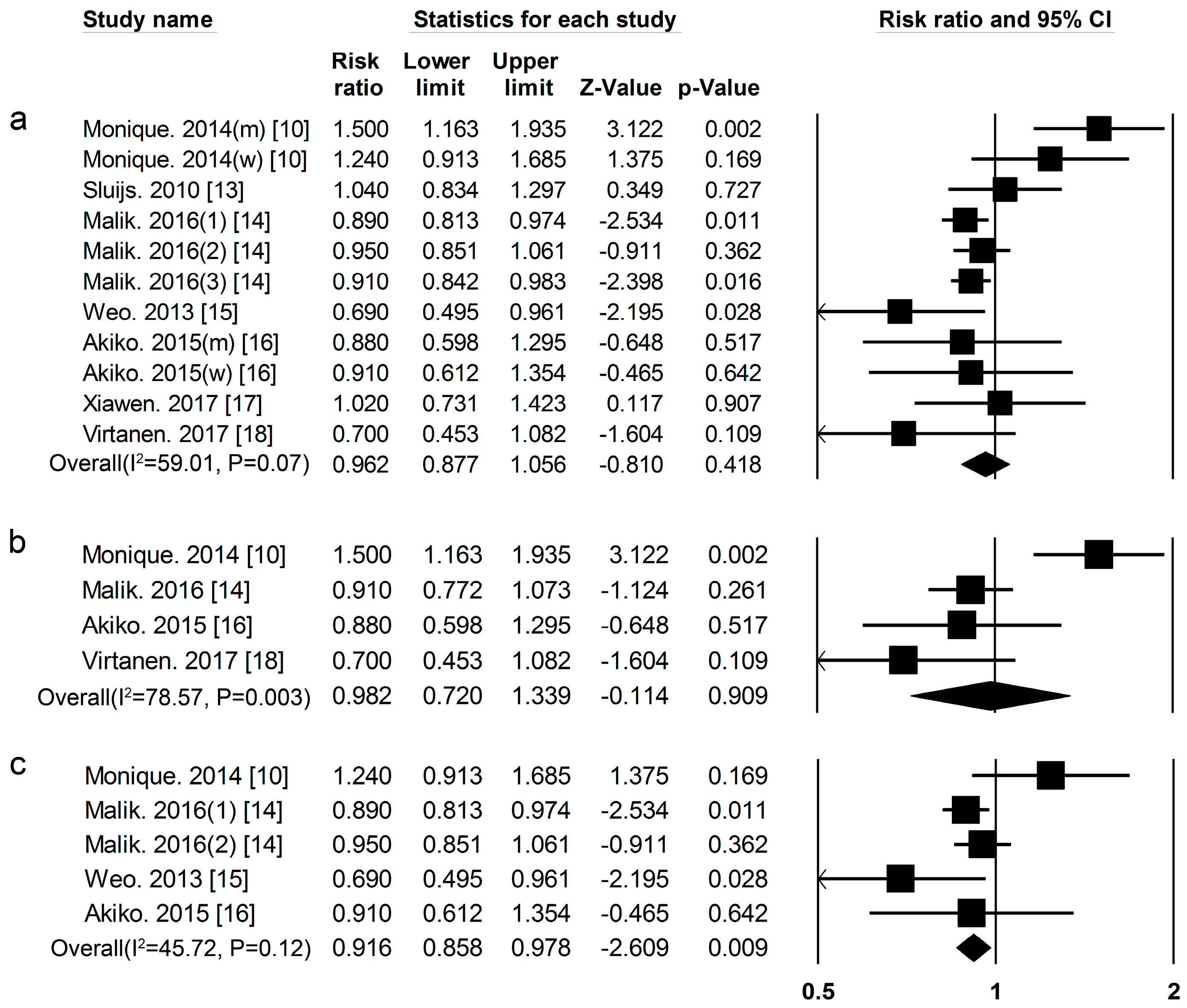

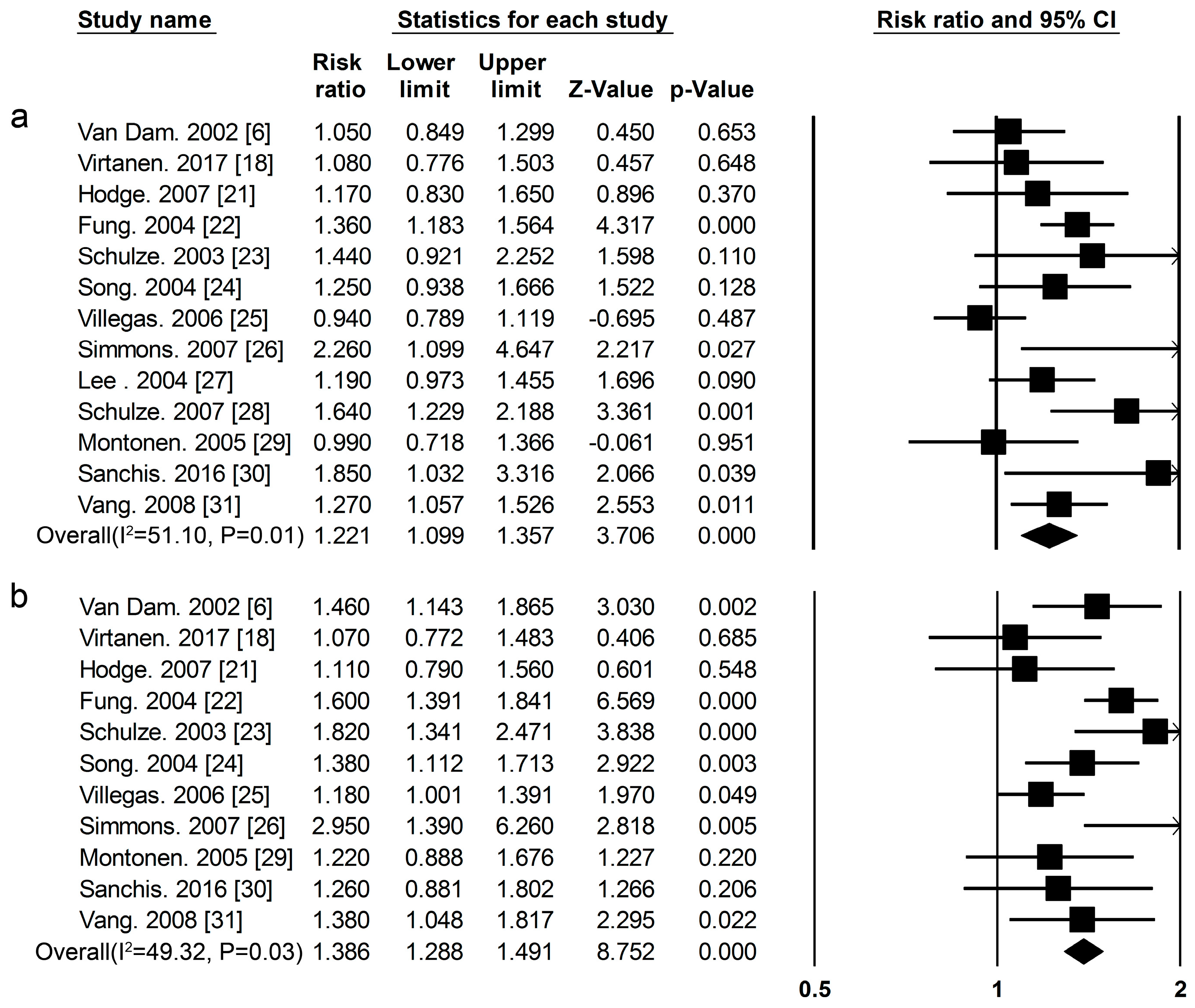

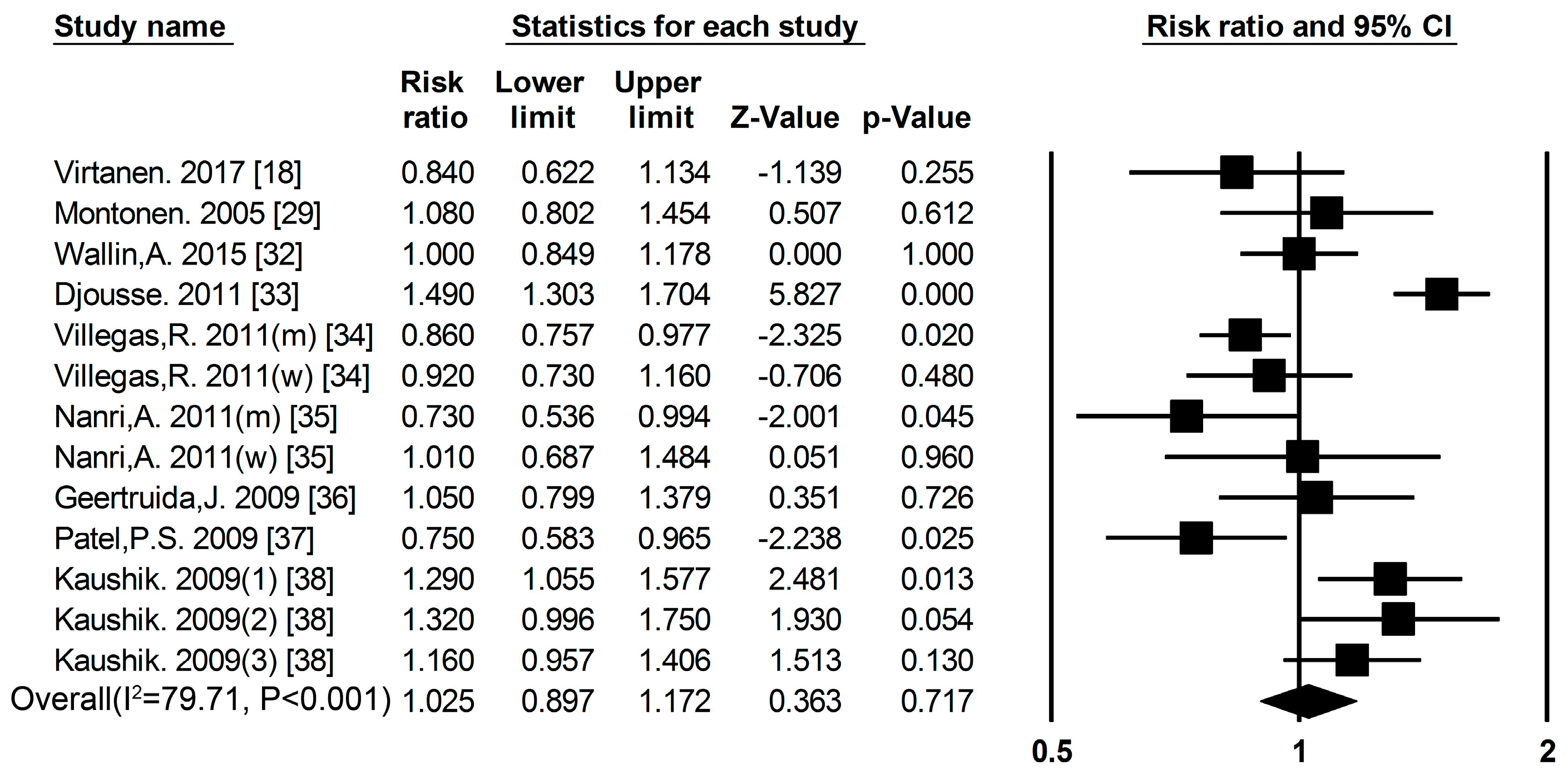

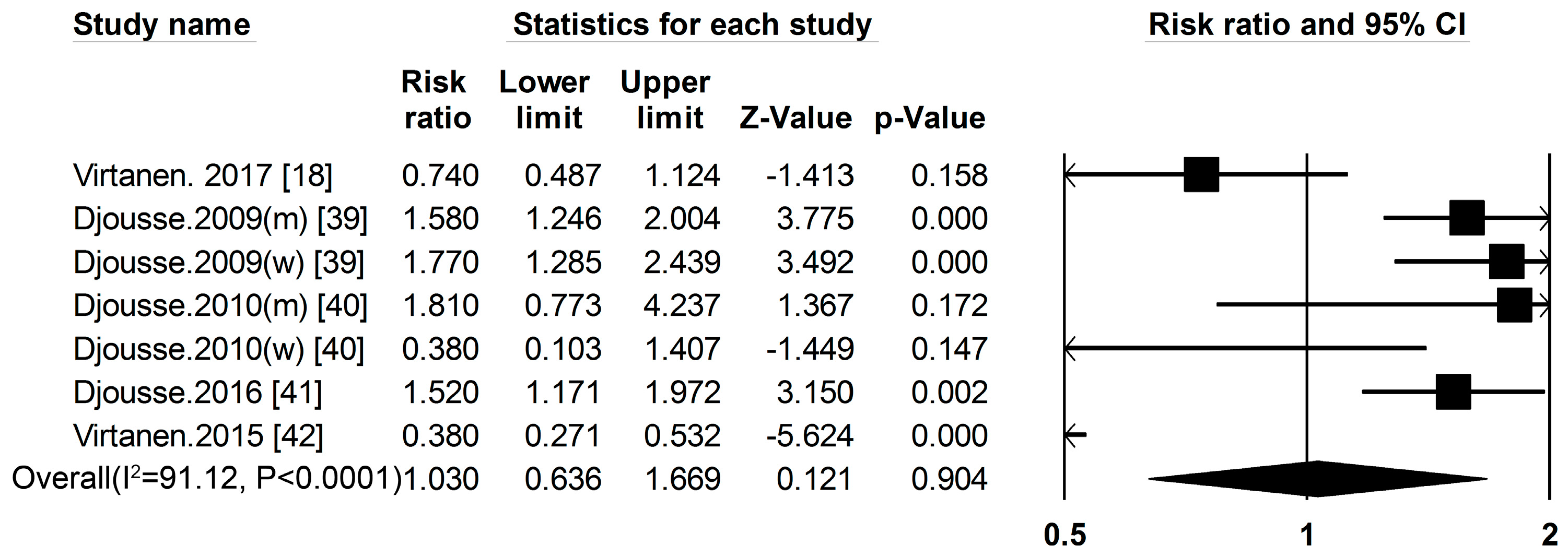

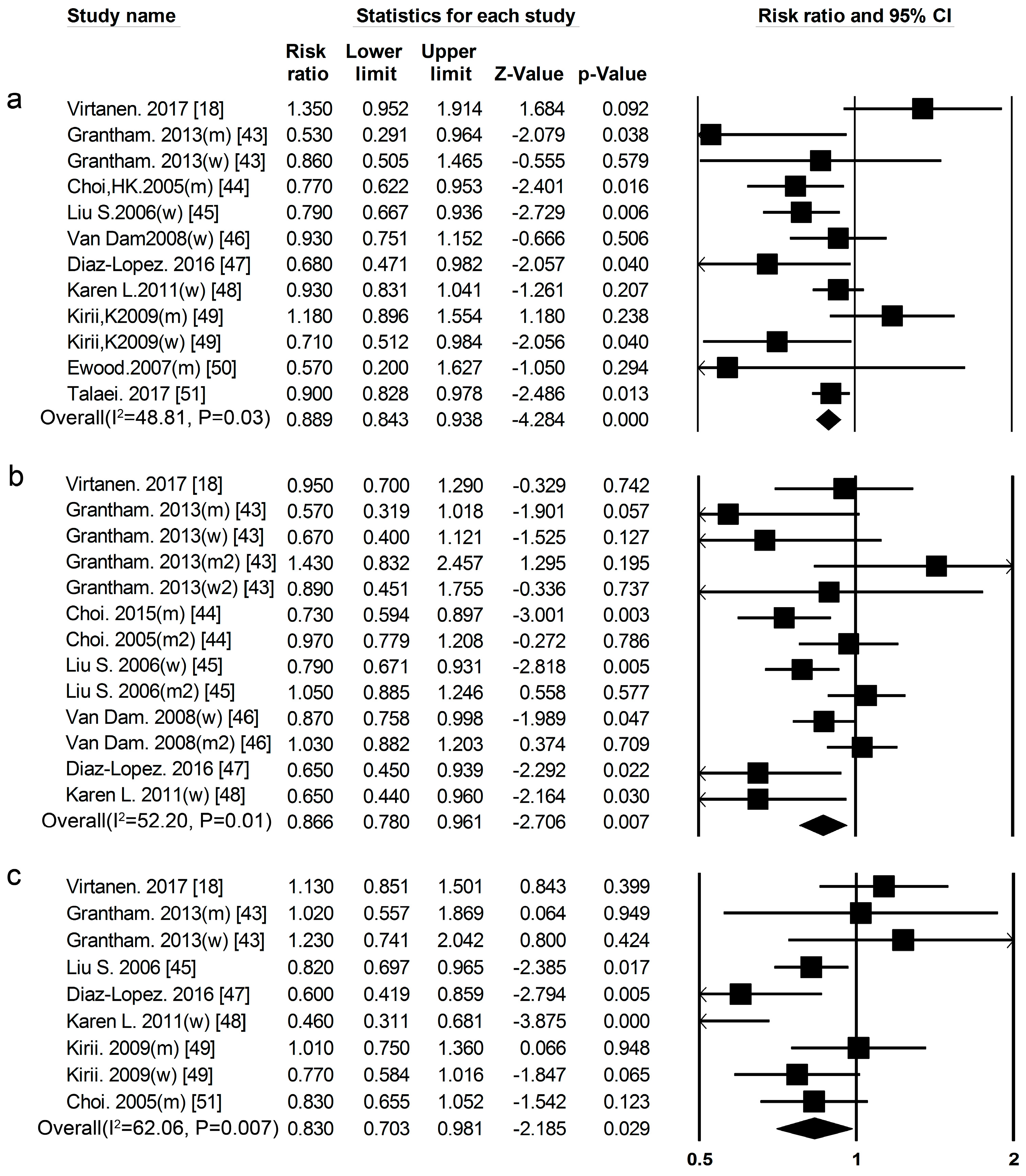

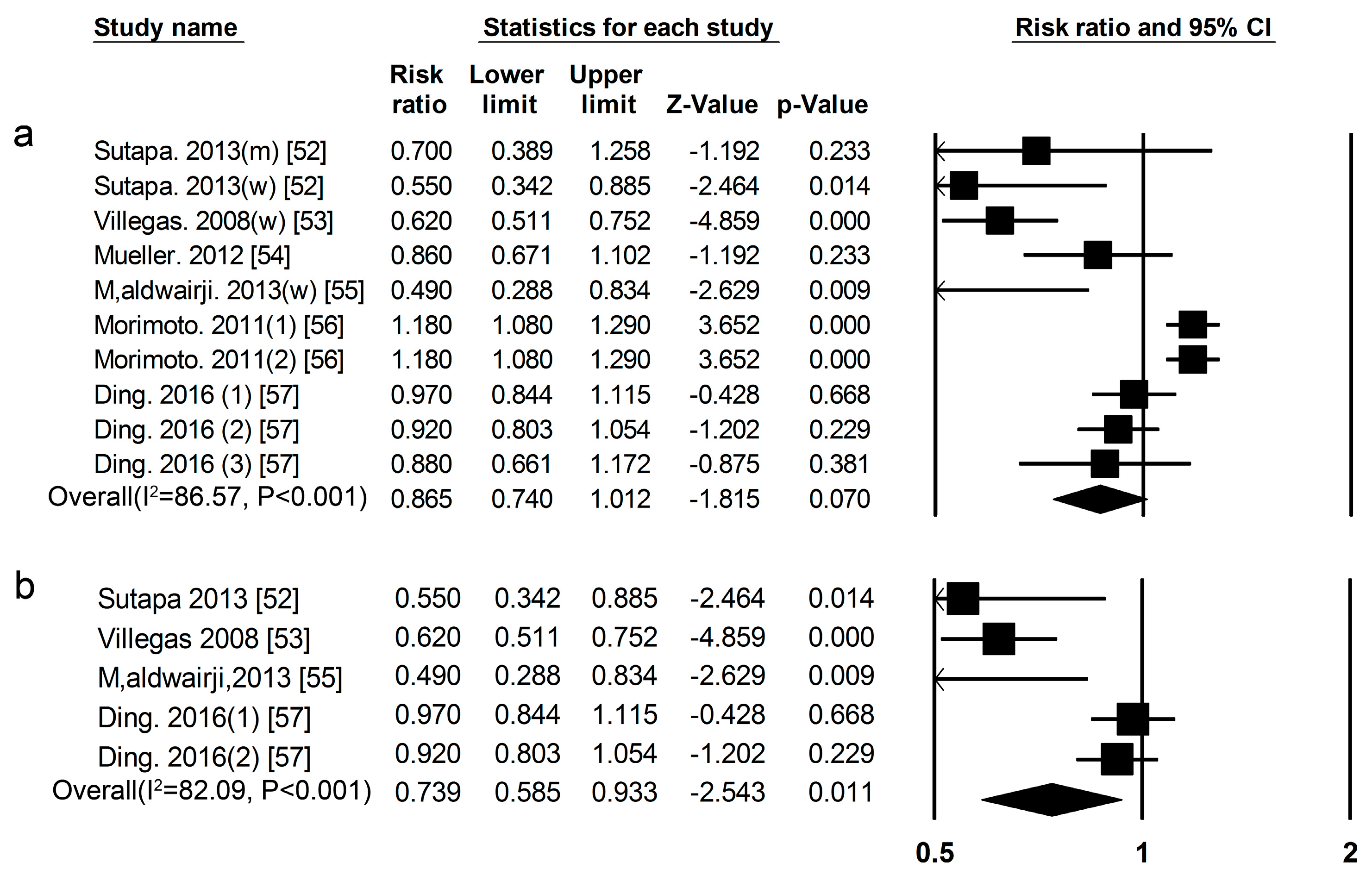

3.2. High-Protein Food and Risk of T2DM

3.3. Publication Bias

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guariguata, L.; Whiting, D.R.; Hambleton, I.; Beagley, J.; Linnenkamp, U.; Shaw, J.E. Globalestimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 103, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2006. Diabetes Care 2006, 29 (Suppl. 1), S4–S42. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, G.A.; Glauber, H.S.; Brown, J.B. Type 2 diabetes: Incremental medical care costs during the 8 years preceding diagnosis. Diabetes Care 2002, 23, 1654–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomilehto, J.; Lindström, J.; Eriksson, J.G.; Valle, T.T.; Hämäläinen, H.; Ilanne-Parikka, P.; Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S.; Laakso, M.; Louheranta, A.; Rastas, M.; et al. Prevention of: Type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 344, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, M.B.; Schulz, M.; Heidemann, C.; Schienkiewitz, A.; Hoffmann, K.; Boeing, H. Carbohydrate intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dam, R.M.; Willett, W.C.; Rimm, E.B.; Stampfer, M.J.; Hu, F.B. Dietary fat and meat intake in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes in men. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weickert, M.O.; Roden, M.; Isken, F.; Hoffmann, D.; Nowotny, P.; Osterhoff, M.; Blaut, M.; Alpert, C.; Gögebakan, Ö.; Bumke-Vogt, C.; et al. Effects of supplemented isoenergetic diets differing in cereal fiber and protein content on insulin sensitivity in overweight humans. Am. J. Nutr. 2011, 94, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuttal, F.Q.; Schweim, K.; Hoover, H.; Gannon, M.C. Effect of the LoBAG30 diet on blood glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pounis, G.D.; Tyrovolas, S.; Antonopoulou, M.; Zeimbekis, A.; Anastasiou, F.; Bountztiouka, V.; Metallinos, G.; Gotsis, E.; Lioliou, E.; Polychronopoulos, E.; et al. Long-term animal-protein consumption is associated with an increased prevalence of diabetes among the elderly: The Mediterranean islands (MEDIS) study. Diabetes Metab. 2010, 36, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Nielen, M.; Feskens, E.J.; Mensink, M.; Sluijs, I.; Molina, E.; Amiano, P.; Ardanaz, E.; Balkau, B.; Beulens, J.W.; Boeing, H.; et al. Dietary protein intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes in Europe: The EPIC-InterAct Case-Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1854–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericson, U.; Sonestedt, E.; Gullberg, B.; Hellstrand, S.; Hindy, G.; Wirfalt, E.; Orho, M. High intakes of protein and processed meat associate with increased incidence of type 2 diabetes. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 1143–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinker, L.F.; Sarto, G.E.; Howard, B.V.; Huang, Y.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Beasley, J.M.; Margolis, K.L.; Eaton, C.B.; Phillips, L.S.; et al. Biomarker-calibrated dietary energy and protein intake associations with diabetes risk among postmenopausal women from the Women’s Health Initiative. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1600–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluijs, I.; Beulens, J.W.; Spijkerman, A.M.; Grobbee, D.E.; van der Schouw, Y.T. Dietary intake of total, animal, and vegetable protein and risk of type 2 diabetes in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition(EPIC)-NL study. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, V.; Li, Y.; Tobias, D.; Pan, A.; Hu, F. Dietary protein intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in U.S. men and women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 183, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, W.; Bowers, K.; Tobias, D.; Hu, F.; Zhang, C. Prepregnancy dietary protein intake, major dietary protein sources, and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: A Prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 2001–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanri, A.; Mizoue, T.; Kurotani, K.; Goto, A.; Oba, S.; Noda, M.; Sawada, N.; Tsugane, S. Low-carbohydrate diet and type 2 diabetes risk in Japanese men and women: The Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, X.; Scott, D.; Hodge, A.M.; English, D.R.; Giles, G.G.; Ebeling, P.R.; Sanders, K.M. Dietary protein intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: Results from Melboune Collaborative Cohort study and a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1352–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virtanen, H.E.; Koskinen, T.T.; Voutilainen, S.; Mursu, J.; Tuomainen, T.P.; Kokko, P.; Virtanen, J.K. Intake of different dietary proteins and risk of type 2 diabetes in men: The Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Der Simonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodge, A.M.; English, D.R.; O’Dea, K.; Giles, G.G. Dietary patterns and diabetes incidence in the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 165, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.T.; Schulze, M.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Dietary patterns, meat intake, and the risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 2235–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, M.B.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Processed meat intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes in younger and middle-aged women. Diabetologia 2003, 46, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Manson, J.E.; Buring, J.E.; Liu, S. A prospective study of red meat consumption and type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and elderly women: The women’s health study. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 2108–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villegas, R.; Shu, X.O.; Gao, Y.T.; Yang, G.; Cai, H.; Li, H.; Zheng, W. The association of meat intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes may be modified by body weight. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2006, 3, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, R.K.; Harding, A.H.; Wareham, N.J.; Griffin, S.J. Do simple questions about diet and physical activity help to identify those at risk of type 2 diabetes? Diabet. Med. 2007, 24, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Folsom, A.R.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr. Dietary iron intake and type 2 diabetes incidence in postmenopausal women: The Iowa Women’s Health Study. Diabetologia 2004, 47, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, M.B.; Hoffmann, K.; Boeing, H.; Linseisen, J.; Rohrmann, S.; Möhlig, M.; Pfeiffer, A.F.; Spranger, J.; Thamer, C.; Häring, H.U.; et al. An accurate risk score based on anthropometric, dietary, and lifestyle factors to predict the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montonen, J.; Jarvinen, R.; Heliovaara, M.; Reunanen, A.; Aromaa, A.; Knekt, P. Food consumption and the incidence of type II diabetes mellitus. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mari-Sanchis, A.; Gea, A.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Beunza, J.J.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Meat consumption and risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the SUN Project: A highly educated middle-class population. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vang, A.; Singh, P.N.; Lee, J.W.; Haddad, E.H.; Brinegar, C.H. Meats, processed meats, obesity, weight gain and occurrence of diabetes among adults: Findings from adventist health studies. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 52, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallin, A.; Di Giuseppe, D.; Orsini, N.; Åkesson, A.; Forouhi, N.G.; Wolk, A. Fish consumption and frying of fish in relation to type 2 diabetes incidence: A prospective cohort study of Swedish men. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djoussé, L.; Gaziano, J.M.; Buring, J.E.; Lee, I.M. Dietary omega-3 fatty acids and fish consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villegas, R.; Xiang, Y.; Elasy, T.; Li, H.; Yang, G.; Cai, H.; Ye, F.; Gao, Y.; Shyr, Y.; Zheng, W.; et al. Fish, shellfish, and long-chain n-3 fatty acid consumption and risk of incident type 2 diabetes in middle-aged Chinese men and women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanri, A.; Mizoue, T.; Noda, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Poudel, T.; Kato, M.; Oba, S.; Inoue, M.; Tsugane, S. Fish intake and type 2 diabetes in Japanese men and women: The Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geertruida, J.; Ballegooijen, A.; Kuijsten, A.; Sijbrands, E.; Rooij, F.; Geleijnse, J.; Hofman, A.; Witteman, J.; Fesken, E. Eating fish and risk of type 2 diabetes: A population-based, prospective follow-up study. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 2021–2026. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, P.; Sharp, S.; Luben, R.; Khaw, K.; Bingham, S.; Wareham, N.; Forouhi, N. Association between type of dietary fish and seafood intake and the risk of incident type 2 diabetes: The European prospective investigation of cancer (EPIC)-Norfolk cohort study. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 1857–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, M.; Mozaffarian, D.; Spiegelman, D.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Long chain omega-3 fatty acids, fish intake, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djousse, L.; Gaziano, J.M.; Buring, J.E.; Lee, I.M. Egg consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in men and women. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djoussé, L.; Kamineni, A.; Nelson, T.L.; Carnethon, M.; Mozaffarian, D.; Siscovick, D.; Mukamal, K.J. Egg consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in older adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djousse, L.; Petrone, A.; Hickson, D.; Talegawkar, S.; Dubbert, P.; Taylor, H.; Tucker, K. Egg consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes among African Americans: The Jackson Heart Study. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 53, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virtanen, J.; Mursu, J.; Tuomainen, T.; Virtanen, H.; Voutilainen, S. Egg consumption and risk of incident type 2 diabetes in men: The Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grantham, N.; Magliano, D.; Hodge, A.; Jowett, J.; Meikle, P.; shaw, J. The association between dairy food intake and the incidence of diabetes in Australia: The Australian Diabetes Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.K.; Willett, W.C.; Stampfer, M.J.; Rimm, E.; Hu, F.B. Dairy consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in men: A prospective study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Choi, H.K.; Ford, E.; Song, Y.; Klevak, A.; Buring, J.E.; Manson, J.E. A prospective study of dairy intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1579–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dam, R.M.; Hu, F.B.; Rosenberg, L.; Krishnan, S.; Palmer, J.R. Dietary calcium and magnesium, major food sources, and risk of type 2 diabetes in U.S. black women. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 2238–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-López, A.; Bulló, M.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Estruch, R.; Fitó, M.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Fiol, M.; de la Corte, F.J.G.; Ros, E.; et al. Dairy product consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in an elderly Spanish Mediterranean population at high cardiovascular risk. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolis, K.L.; Wei, F.; de Boer, I.H.; Howard, B.V.; Liu, S.; Manson, J.E.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Phillips, L.S.; Shikany, J.M.; Tinker, L.F. A diet high in low-fat dairy products lowers diabetes risk in postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1969–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirii, K.; Mizoue, T.; Iso, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Kato, M.; Inoue, M.; Noda, M.; Tsugane, S.; Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study Group. Calcium, vitamin D and dairy intake in relation to type 2 diabetes risk in a Japanese cohort. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 2542–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwood, P.C.; Pickering, J.E.; Fehily, A.M. Milk and dairy consumption, diabetes and the metabolic syndrome: The Caerphilly prospective study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talaei, M.; Pan, A.; Yuan, J.M.; Koh, W.P. Dairy intake and risk of type 2 diabetes. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutapa, A.; Shah, E. Association between legume intake and self-reported diabetes among adult men and women in India. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 706. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas, R.; Gao, Y.; Yang, G.; Li, H.; Elasy, T.; Zheng, W.; Shu, X. Legume and soy food intake and the incidence of type 2 diabetes in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mueller, N.; Odegaard, A.; Gross, M.; Koh, W.; Yu, M.; Yuan, J.; Pereira, M. Soy intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in Chinese Singaporeans. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldwairji, M.; Orfila, C.; Burley, V.J. Legume intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in British women. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, E275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, Y.; Steinbrecher, A.; Kolonel, L.; Maskarinec, G. Soy consumption is not protective against diabetes in Hawaii: The Multiethnic Cohort. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, M.; Pan, A.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Malik, V.; Rosner, B.; Giovannucci, E.; Hu, F.B.; Sun, Q. Consumption of soy foods and isoflavones and risk of type 2diabetes: A pooled analysis of three U.S. cohorts. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartemink, N.; Boshuizen, H.C.; Nagelkerke, N.J.; Jacobs, M.A.; van Houwelingen, H.C. Combining risk estimates from observational studies with different exposure cutpoints: A meta-analysis on body mass index and diabetes type 2. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 163, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linn, T.; Geyer, R.; Prassek, S.; Laube, H. Effect of dietary protein intake on insulin secretion and glucose metabolism in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1996, 81, 3938–3943. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Linn, T.; Santosa, B.; Grönemeyer, D.; Aygen, S.; Scholz, N.; Busch, M.; Bretzel, R.G. Effect of long-term dietary protein intake on glucose metabolism in humans. Diabetologia 2000, 43, 1257–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patti, M.E.; Brambilla, E.; Luzi, L.; Landaker, E.J.; Kahn, C.R. Bidirectional modulation of insulin action by amino acids. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takano, A.; Usui, I.; Haruta, T.; Kawahara, J.; Uno, T.; Iwata, M.; Kobayashi, M. Mammalian target of rapamycin pathway regulates insulin signaling via subcellular redistribution of insulin receptor substrate 1 and integrates nutritional signals and metabolic signals of insulin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 5050–5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, F.; Krebs, M.; Dombrowski, L.; Brehm, A.; Bernroider, E.; Roth, E.; Nowotny, P.; Waldhäusl, W.; Marette, A.; Roden, M. Overactivation of S6 kinase 1 as a cause of human insulin resistance during increased amino acid availability. Diabetes 2005, 54, 2674–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, F.; Marette, A. Amino acid and insulin signaling via the mTOR/p70 S6 kinase pathway. A negative feedback mechanism leading to insulin resistance in skeletal muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 38052–38060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Um, S.H.; D’Alessio, D.; Thomas, G. Nutrient overload, insulin resistance, and ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1, S6K1. Cell Metab. 2006, 3, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulve, E.A.; Cartee, G.D.; Holloszy, J.O. Prolonged incubation of skeletal muscle in vitro: Prevention of increases in glucose transport. Am. J. Physiol. 1991, 261, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Gannon, M.C.; Nuttall, F.Q. Effect of a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet on blood glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2004, 53, 2375–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuttall, F.Q.; Gannon, M.C. Metabolic response of people with type 2 diabetes to a high-protein diet. Nutr. Metab. 2004, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, F.; Lavigne, C.; Jacques, H.; Marette, A. Role of dietary proteins and amino acids in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2007, 27, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, C.K.; Skulas-Ray, A.C.; Champagne, C.M.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Plantprotein and animal proteins: Do they differentially affect cardiovascular disease risk? Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 712–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newgard, C.B. Interplay between lipids and branched-chain amino acids in development of insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittenbecher, C.; Muhlenbruch, K.; Kroger, J.; Jacobs, S.; Kuxhaus, O.; Floegel, A.; Fritsche, A.; Pischon, T.; Prehn, C.; Adamski, J.; et al. Amino acids, lipid metabolites, and ferritin as potential mediators linking red meat consumption to type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamler, J.; Brown, I.J.; Daviglus, M.L.; Chan, Q.; Miura, K.; Okuda, N.; Ueshima, H.; Zhao, L.; Elliott, P. Dietary glycine and blood pressure: The international study on macro/micronutrients and blood pressure. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, A.; MacGregor, A.; Welch, A.; Chowienczyk, P.; Spector, T.; Cassidy, A. Amino acid intakes are inversely associated with arterial stiffness and central blood pressure in women. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2130–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azadbakht, L.; Atabak, S.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Soy protein intake, cardiorenal indices, and C-reactive protein in type 2 diabetes with nephropathy: A longitudinal randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, M.L.; Fineberg, S.E.; Fineberg, N.S.; Gibson, R.G.; Hackward, L.L. Animal versus plant protein meals in individuals with type 2 diabetesand microalbuminuria: Effects on renal, glycemic, and lipid parameters. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sucher, S.; Markova, M.; Hornemann, S.; Pivovarova, O.; Rudovich, N.; Thomann, R.; Schneeweiss, R.; Rohn, S.; Pfeiffer, A.F. Compar ison of the effects of diets high in animal or plantprotein on metaboli c and cardiov ascular markers in type 2diabetes: A randomize clinical trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2017, 19, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Hao, T.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2392–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, A.M.; Pan, A.; Rexrode, K.M.; Stampfer, M.; Hu, F.B.; Mozaffarian, D.; Willett, W.C. Dietary protein sources and the risk of stroke in men and women. Stroke 2012, 43, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, A.M.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B.; Stampfer, M.J.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C. Major dietary protein sources and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Circulation 2010, 122, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, A.; Sun, Q.; Bernstein, A.M.; Schulze, M.B.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Red meat consumption and mortality: Results from 2 prospective cohort studies. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pan, A.; Sun, Q.; Bernstein, A.M.; Schulze, M.B.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Red meat consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: 3 cohorts of U.S. adults and an updated meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forouhi, N.G.; Harding, A.H.; Allison, M.; Sandhu, M.S.; Welch, A.; Luben, R.; Bingham, S.; Khaw, K.T.; Wareham, N.J. Elevated serum ferritin levels predict new-onset type 2 diabetes: Results from the EPIC-Norfolk prospective study. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, M.; Holmboe-Ottesen, G. Egg consumption and the risk of diabetes in adults, Jiangsu, China. Nutrition 2011, 27, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radzeviciene, L.; Ostrauskas, R. Egg consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A case-control study. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1437–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001, 285, 2486–2497. [Google Scholar]

- Grundy, S.; Becker, D.; Clark, L.T.; Cooper, R.S.; Denke, M.A.; Howard, J.; Hunninghake, D.B.; Illingworth, D.R.; Luepker, R.V.; McBride, P.; et al. Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Final Report. Circulation 2002, 106, 3143. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, R.M.; Deckelbaum, R.J.; Ernst, N.; Fisher, E.; Howard, B.V.; Knopp, R.H.; Kotchen, T.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; McGill, H.C.; Pearson, T.A.; et al. Dietary guidelines for healthy American adults. A statement for health professionals from the Nutrition Committee, American heart association. Circulation 1996, 94, 1795–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luhovyy, B.L.; Akhavan, T.; Anderson, G.H. Whey proteins in the regulation of food intake and satiety. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007, 26, 704S–712S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, M.; Sakaue, H. Role of vitamin D and calciumin obesity and type 2 diabetes. Clin. Calcium 2016, 26, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berr, C.; Akbaraly, T.; Arnaud, J.; Hininger, I.; Roussel, A.M.; Gateau, P.B. Increased selenium intake in elderly high fish consumers may account for health benefits previously ascribed to omega-3 fatty acids. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleys, J.; Navas-Acien, A.; Guallar, E. Serum selenium and diabetes in U.S. adults. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhathena, S.J.; Velasquez, M.T. Beneficial role of dietary phytoestrogens in obesity and diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jayagopal, V.; Albertazzi, P.; Kilpatrick, E.S.; Howarth, E.M.; Jennings, P.E.; Hepburn, D.A.; Atkin, S.L. Beneficial effects of soy phytoestrogen intake in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1709–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Proteins and Foods Sources | Begg-Mazumdar’s Test | Egger’s Test |

|---|---|---|

| Total protein (all) | 0.74 | 0.38 |

| Total protein (men) | 0.46 | 0.74 |

| Total protein (women) | 0.55 | 0.33 |

| Animal protein (all) | 0.64 | 0.07 |

| Animal protein (men) | 0.73 | 0.57 |

| Animal protein (women) | 0.22 | 0.10 |

| Plant protein (all) | 0.76 | 0.50 |

| Plant protein (men) | 0.73 | 0.90 |

| Plant protein (women) | 0.81 | 0.91 |

| Red meat | 0.30 | 0.33 |

| Processed meat | 0.88 | 0.99 |

| Fish | 0.58 | 0.43 |

| Total dairy product | 0.45 | 0.43 |

| Whole milk | 0.67 | 0.35 |

| Yogurt | 0.92 | 0.99 |

| Egg | 0.23 | 0.50 |

| Soy | 0.46 | 0.13 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, S.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, R.; Han, T.; Sun, C.; Na, L. Dietary Protein Consumption and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Nutrients 2017, 9, 982. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9090982

Tian S, Xu Q, Jiang R, Han T, Sun C, Na L. Dietary Protein Consumption and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Nutrients. 2017; 9(9):982. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9090982

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Shuang, Qian Xu, Ruyue Jiang, Tianshu Han, Changhao Sun, and Lixin Na. 2017. "Dietary Protein Consumption and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies" Nutrients 9, no. 9: 982. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9090982

APA StyleTian, S., Xu, Q., Jiang, R., Han, T., Sun, C., & Na, L. (2017). Dietary Protein Consumption and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Nutrients, 9(9), 982. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9090982