Comparing the Nutritional Impact of Dietary Strategies to Reduce Discretionary Choice Intake in the Australian Adult Population: A Simulation Modelling Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

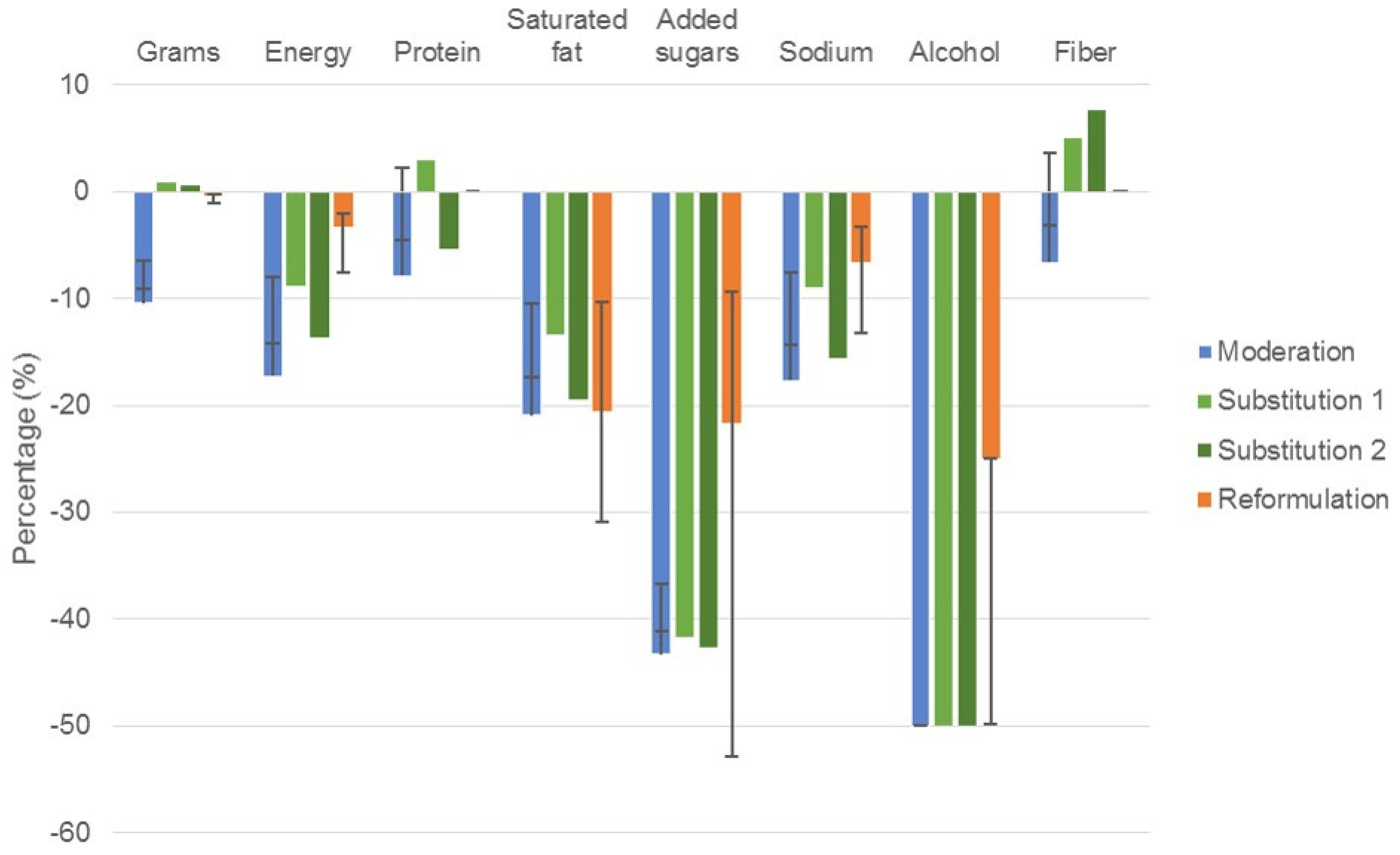

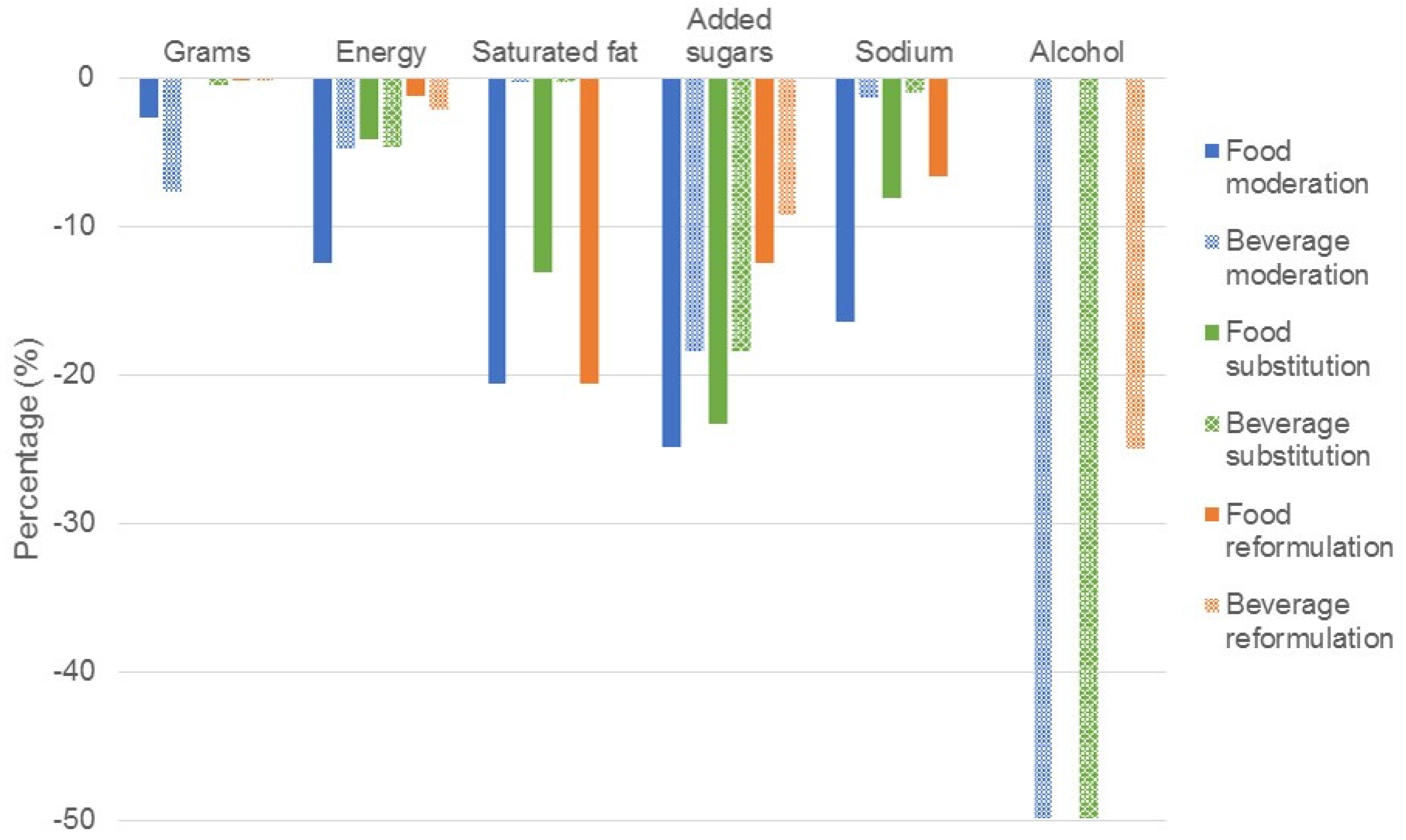

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Government; National Health and Medical Research Council; Department of Health and Ageing. Eat for Health. Australian Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/the_guidelines/n55_australian_dietary_guidelines.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2016).

- World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. Available online: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/trs916/en/ (accessed on 14 March 2016).

- Public Health England; UK’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. The Eatwell Guide. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-eatwell-guide (accessed on 12 April 2017).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 8th ed.; 2015. Available online: http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/ (accessed on 12 April 2017).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4364.0.55.007—Australian Health Survey: Nutrition First Results—Foods and Nutrients, 2011–12. 2013. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4364.0.55.007~2011-12~Main%20Features~Discretionary%20foods~700 (accessed on 12 December 2015).

- Rangan, A.M.; Randall, D.; Hector, D.J.; Gill, T.P.; Webb, K.L. Consumption of ‘extra’ foods by Australian children: Types, quantities and contribution to energy and nutrient intakes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangan, A.M.; Schindeler, S.; Hector, D.J.; Gill, T.P.; Webb, K.L. Consumption of ‘extra’ foods by Australian adults: Types, quantities and contribution to energy and nutrient intakes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, Z.; Wong, W.K.; Louie, J.C.; Rangan, A. Discretionary food and beverage consumption and its association with demographic characteristics, weight status, and fruit and vegetable intakes in Australian adults. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, R.; Maurer, G. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and discretionary foods among US adults by purchase location. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1396–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, J.A.; Pedraza, L.S.; Aburto, T.C.; Batis, C.; Sanchez-Pimienta, T.G.; Gonzalez de Cosio, T.; Lopez-Olmedo, N.; Pedroza-Tobias, A. Overview of the Dietary Intakes of the Mexican Population: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1851S–1855S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitton, C.; Nicholson, S.K.; Roberts, C.; Prynne, C.J.; Pot, G.K.; Olson, A.; Fitt, E.; Cole, D.; Teucher, B.; Bates, B.; et al. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: UK food consumption and nutrient intakes from the first year of the rolling programme and comparisons with previous surveys. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 1899–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sichieri, R.; Bezerra, I.N.; Araujo, M.C.; de Moura Souza, A.; Yokoo, E.M.; Pereira, R.A. Major food sources contributing to energy intake—A nationwide survey of Brazilians aged 10 years and older. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1638–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friel, S.; Barosh, L.J.; Lawrence, M. Towards healthy and sustainable food consumption: An Australian case study. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrie, G.A.; Baird, D.; Ridoutt, B.; Hadjikadou, M.; Noakes, M. Overconsumption of Energy and Excessive Discretionary Food Intake Inflates Dietary Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Australia. Nutrients 2016, 8, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.J.; Kane, S.; Ramsey, R.; Good, E.; Dick, M. Testing the price and affordability of healthy and current (unhealthy) diets and the potential impacts of policy change in Australia. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biehl, E.; Klemm, R.D.; Manohar, S.; Webb, P.; Gauchan, D.; West, K.P. What Does It Cost to Improve Household Diets in Nepal? Using the Cost of the Diet Method to Model Lowest Cost Dietary Changes. Food Nutr. Bull. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenbach, J.D.; Burgoine, T.; Lakerveld, J.; Forouhi, N.G.; Griffin, S.J.; Wareham, N.J.; Monsivais, P. Accessibility and Affordability of Supermarkets: Associations With the DASH Diet. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, T.; Trevena, H.; Sacks, G.; Dunford, E.; Martin, J.; Webster, J.; Swinburn, B.; Moodie, A.R.; Neal, B.C. A systematic interim assessment of the Australian Government’s Food and Health Dialogue. Med. J. Aust. 2014, 200, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.; Magnusson, R.; Swinburn, B.; Webster, J.; Wood, A.; Sacks, G.; Neal, B. Designing a Healthy Food Partnership: Lessons from the Australian Food and Health Dialogue. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, B.J.; Grunseit, A.; Phongsavan, P.; Bellew, W.; Briggs, M.; Bauman, A.E. Impact of the Swap It, Don’t Stop It Australian National Mass Media Campaign on Promoting Small Changes to Lifestyle Behaviors. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 1276–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieger, J.A.; Wycherley, T.P.; Johnson, B.J.; Golley, R.K. Discrete strategies to reduce intake of discretionary food choices: A scoping review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieger, J.A.J.; Johnson, B.J.; Wycherley, T.P.; Golley, R.K. Evaluation of simulation models estimating the effect of dietary strategies on nutritional intake: A systematic review. J. Nutr. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, L.; Michie, S. Designing interventions to change eating behaviours. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2015, 74, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homer, J.B.; Hirsch, G.B. System dynamics modeling for public health: Background and opportunities. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, D.T.; Bauer, J.E.; Lee, H.R. Simulation modeling and tobacco control: Creating more robust public health policies. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, E.; Warnberg, J.; Kearney, J.; Sjostrom, M. Sources of saturated fat and sucrose in the diets of Swedish children and adolescents in the European Youth Heart Study: Strategies for improving intakes. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1955–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.J.; Brinsden, H.C.; MacGregor, G.A. Salt reduction in the United Kingdom: A successful experiment in public health. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2014, 28, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Spangler, C.M.; Juusola, J.L.; Enns, E.A.; Owens, D.K.; Garber, A.M. Population strategies to decrease sodium intake and the burden of cardiovascular disease: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 152, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyness, L.A.; Butriss, J.L.; Stanner, S.A. Reducing the population’s sodium intake: The UK Food Standards Agency’s salt reduction programme. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yach, D.; Khan, M.; Bradley, D.; Hargrove, R.; Kehoe, S.; Mensah, G. The role and challenges of the food industry in addressing chronic disease. Glob. Health 2010, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4363.0.55.001—Australian Health Survey: Users’ Guide, 2011–13. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4363.0.55.001 (accessed on 12 December 2015).

- Bliss, R. Researchers produce innovation in dietary recall. Agric. Res. 2004, 52, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. AUSNUT 2011-2013. Available online: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science/monitoringnutrients/ausnut/pages/default.aspx (accessed on 20 March 2015).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 43630DO005_20112013 Australian Health Survey: Users’ Guide, 2011–13—Discretionary Food List, Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4363.0.55.001Chapter65062011-13 (acccessed on 12 December 2015).

- Heart Foundation. Rapid Review of the Evidence: Effectiveness of Food Reformulation as a Strategy to Improve Population Health. 2012. Available online: https://heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/publications/RapidReview_FoodReformulation.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2016).

- Van Raaij, J.; Hendriksen, M.; Verhagen, H. Potential for improvement of population diet through reformulation of commonly eaten foods. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Food for Health: Dietary Guidelines for Australians, A Guide to Healthy Eating. 2005. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/n31.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2016).

- Flood, J.E.; Roe, L.S.; Rolls, B.J. The effect of increased beverage portion size on energy intake at a meal. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1984–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, A.M.; Shannon, E.; Whybrow, S.; Reid, C.A.; Stubbs, R.J. Altering the temporal distribution of energy intake with isoenergetically dense foods given as snacks does not affect total daily energy intake in normal-weight men. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 83, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Raben, A.; Vasilaras, T.H.; Moller, A.C.; Astrup, A. Sucrose compared with artificial sweeteners: Different effects on ad libitum food intake and body weight after 10 wk of supplementation in overweight subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomson, J.L.; Tussing-Humphreys, L.M.; Onufrak, S.J.; Zoellner, J.M.; Connell, C.L.; Bogle, M.L.; Yadrick, K. A simulation study of the potential effects of healthy food and beverage substitutions on diet quality and total energy intake in Lower Mississippi Delta adults. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 2191–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government. Food and Health Dialogue. 2011. Available online: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/Healthy-Food-Partnership-Home (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Lloyd-Williams, F.; Mwatsama, M.; Ireland, R.; Capewell, S. Small changes in snacking behaviour: The potential impact on CVD mortality. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreyeva, T.; Chaloupka, F.J.; Brownell, K.D. Estimating the potential of taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages to reduce consumption and generate revenue. Prev. Med. 2011, 52, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs, A.D.; Mytton, O.T.; Madden, D.; O'Shea, D.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. The potential impact on obesity of a 10% tax on sugar-sweetened beverages in Ireland, an effect assessment modelling study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, B.; Capewell, S.; O'Flaherty, M.; Timpson, H.; Razzaq, A.; Cheater, S.; Ireland, R.; Bromley, H. Modelling the Health Impact of an English Sugary Drinks Duty at National and Local Levels. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, E.A.; Zhen, C.; Nonnemaker, J.; Todd, J.E. Impact of targeted beverage taxes on higher- and lower-income households. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 2028–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuchler, F.; Tegene, A.; and Harris, J.M. Taxing Snack Foods: Manipulating Diet Quality or Financing Information Programs? Rev. Agric. Econ. 2005, 27, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, G.; Veerman, J.L.; Moodie, M.; Swinburn, B. Traffic-light nutrition labelling and junk-food tax: A modelled comparison of cost-effectiveness for obesity prevention. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smed, S.; Jensen, J.D.; Denver, S. Socio-economic characteristics and the effect of taxation as a health policy instrument. Food Policy 2007, 32, 624–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government; Department of Health and Ageing and the National Health and Medical Research Council. Nutrient Reference Values Australia and New Zealand. 2005. Available online: https://www.nrv.gov.au/nutrients (accessed on 28 March 2017).

- Levy, D.T.; Friend, K.B. Simulation Modeling of Policies Directed at Youth Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2013, 51, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonnen, T.A.; Odden, M.C.; Coxson, P.G.; Guzman, D.; Lightwood, J.; Wang, Y.C.; Bibbins-Domingo, K. Health benefits of reducing sugar-sweetened beverage intake in high risk populations of California: Results from the Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) policy model. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruff, R.R.; Zhen, C. Estimating the effects of a calorie-based sugar-sweetened beverage tax on weight and obesity in New York City adults using dynamic loss models. Ann. Epidemiol. 2015, 25, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallongeville, J.; Dauchet, L.; de Mouzon, O.; Requillart, V.; Soler, L.G. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption: A cost-effectiveness analysis of public policies. Eur. J. Public Health 2011, 21, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, J.D.; Smed, S. Cost-effective design of economic instruments in nutrition policy. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2007, 4, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, T.; Jarosz, C.J.; Simon, P.; Fielding, J.E. Menu labeling as a potential strategy for combating the obesity epidemic: A health impact assessment. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 1680–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roodenburg, A.J.C.; van Ballegooijen, A.J.; Dotsch-Klerk, M.; van der Voet, H.; Seidell, J.C. Modelling of Usual Nutrient Intakes: Potential Impact of the Choices Programme on Nutrient Intakes in Young Dutch Adults. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietinen, P.; Valsta, L.M.; Hirvonen, T.; Sinkko, H. Labelling the salt content in foods: A useful tool in reducing sodium intake in Finland. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 11, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temme, E.H.; van der Voet, H.; Roodenburg, A.J.; Bulder, A.; van Donkersgoed, G.; van Klaveren, J. Impact of foods with health logo on saturated fat, sodium and sugar intake of young Dutch adults. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyles, H.; Ni Mhurchu, C.; Nghiem, N.; Blakely, T. Food pricing strategies, population diets, and non-communicable disease: A systematic review of simulation studies. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenstein, A.H.; Matthan, N.R.; Jalbert, S.M.; Resteghini, N.A.; Schaefer, E.J.; Ausman, L.M. Novel soybean oils with different fatty acid profiles alter cardiovascular disease risk factors in moderately hyperlipidemic subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Under-Reporting in Nutrition Surveys. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Canberra. 2015. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4363.0.55.001Chapter651512011-13 (accessed on 28 March 2017).

| Total Intake 1 Original Intake | Core Choices Original Intake | Discretionary Choices 2 Original Intake | Discretionary Foods Original Intake | Discretionary Beverages Original Intake 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grams (g) | 3337.7 | 2652.2 | 685.5 | 178.8 | 513.6 |

| Energy (kJ) | 8697.8 | 5654.0 | 3043.8 | 2173.5 | 841.9 |

| Protein (g) (%E 4) | 91.0 (17.5) | 75.6 (14.6) | 15.4 (3.0) | 13.5 (2.6) | 0.9 (0.2) |

| Total fat (g) (%E) | 73.8 (32.0) | 47.4 (20.5) | 26.4 (11.4) | 26.1 (11.3) | 0.3 (0.1) |

| Saturated fat (g) (%E) | 27.7 (12.0) | 16.1 (7.0) | 11.6 (5.0) | 11.4 (4.9) | 0.2 (0.1) |

| Carbohydrate (g) (%E) | 225.9 (43.5) | 145.6 (28.0) | 80.4 (15.5) | 56.3 (10.8) | 23.6 (4.5) |

| Total sugars (g) | 102.9 (19.8) | 51.3 (9.9) | 51.5 (9.9) | 30.7 (5.9) | 20.6 (4.0) |

| Added sugars (g) (%E) | 50.6 (9.7) | 6.7 (1.3) | 43.9 (8.4) | 25.2 (4.9) | 18.6 (3.6) |

| Free sugars (g) (%E) | 57.8 (11.1) | 10.8 (2.1) | 47.1 (9.1) | 26.8 (5.2) | 20.2 (3.9) |

| Sodium (mg) | 2430.5 | 1567.1 | 863.5 | 796.8 | 61.6 |

| Alcohol (g) (%E) | 14.4 (4.8) | 0.0 (0.0) | 14.4 (4.8) | 0.0 (0.0) | 14.4 (4.8) |

| Fiber (g) | 22.9 | 19.9 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 0.1 |

| Vitamin A retinol equivalents (µg) | 851.8 | 732.2 | 119.6 | 107.3 | 7.9 |

| Thiamine (vitamin B1) (mg) | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Riboflavin (vitamin B2) (mg) | 1.9 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Niacin equivalents (mg) | 41.4 | 33.5 | 7.9 | 6.2 | 1.4 |

| Dietary folate equivalent (µg) | 609.9 | 529.0 | 80.9 | 74.1 | 4.8 |

| Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) (mg) | 1.5 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) (µg) | 4.5 | 3.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.1 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 102.3 | 86.1 | 16.2 | 3.9 | 12.1 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 10.5 | 7.8 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 0.1 |

| Calcium (mg) | 804.6 | 677.6 | 127.0 | 93.4 | 25.1 |

| Iodine (µg) | 172.3 | 146.5 | 25.8 | 17.9 | 6.5 |

| Iron (mg) | 11.1 | 9.0 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 0.4 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 338.7 | 274.2 | 64.5 | 40.6 | 21.4 |

| Phosphorous (mg) | 1466.9 | 1137.3 | 329.6 | 259.8 | 58.6 |

| Potassium (mg) | 2912.5 | 2345.5 | 567.0 | 413.2 | 141.4 |

| Selenium (µg) | 91.0 | 75.4 | 15.6 | 12.9 | 2.5 |

| Zinc (mg) | 11.0 | 9.3 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 0.1 |

| Moderation of All Discretionary Foods by 50% | Moderation of All Discretionary Beverages by 50% | Replacement of All Discretionary Foods with All Core Foods 2 | Replacement of Discretionary Beverages with Water, or Fruit and Vegetable Juices 3 | Reformulate All Discretionary Foods 4 | Reformulate All Discretionary Beverages 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grams (g) | 3248.3 | 3080.9 | 3384.7 | 3320.8 | 3331.2 | 3329.5 |

| Energy (kJ) | 7610.8 | 8276 | 8341.1 | 8291.9 | 8592.2 | 8513.9 |

| Saturated fat (g) (% E 1) | 22.0 (10.9%) | 27.6 (12.6%) | 24.1 (10.9%) | 27.6 (12.5%) | 22.0 (9.6%) | 27.7 (12.3) |

| Added sugars (g) (% E) | 38.0 (8.4%) | 41.3 (8.4%) | 38.8 (7.8%) | 41.3 (8.3%) | 44.3 (8.6%) | 46.0 (9.0) |

| Sodium (mg) | 2032.1 | 2399.7 | 2233.9 | 2407.3 | 2271.2 | 2429.8 |

| Alcohol (g) (% E) | 14.4 (5.5%) | 7.2 (2.6%) | 14.4 (5.0%) | 7.2 (2.6%) | 14.4 (4.9%) | 10.8 (3.7) |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grieger, J.A.; Johnson, B.J.; Wycherley, T.P.; Golley, R.K. Comparing the Nutritional Impact of Dietary Strategies to Reduce Discretionary Choice Intake in the Australian Adult Population: A Simulation Modelling Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9050442

Grieger JA, Johnson BJ, Wycherley TP, Golley RK. Comparing the Nutritional Impact of Dietary Strategies to Reduce Discretionary Choice Intake in the Australian Adult Population: A Simulation Modelling Study. Nutrients. 2017; 9(5):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9050442

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrieger, Jessica A., Brittany J. Johnson, Thomas P. Wycherley, and Rebecca K. Golley. 2017. "Comparing the Nutritional Impact of Dietary Strategies to Reduce Discretionary Choice Intake in the Australian Adult Population: A Simulation Modelling Study" Nutrients 9, no. 5: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9050442

APA StyleGrieger, J. A., Johnson, B. J., Wycherley, T. P., & Golley, R. K. (2017). Comparing the Nutritional Impact of Dietary Strategies to Reduce Discretionary Choice Intake in the Australian Adult Population: A Simulation Modelling Study. Nutrients, 9(5), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9050442