Chocolate Consumption and Risk of Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Criteria for Inclusion

2.3. Data Collection and Quality Assessment

2.4. Statistical Method

3. Results

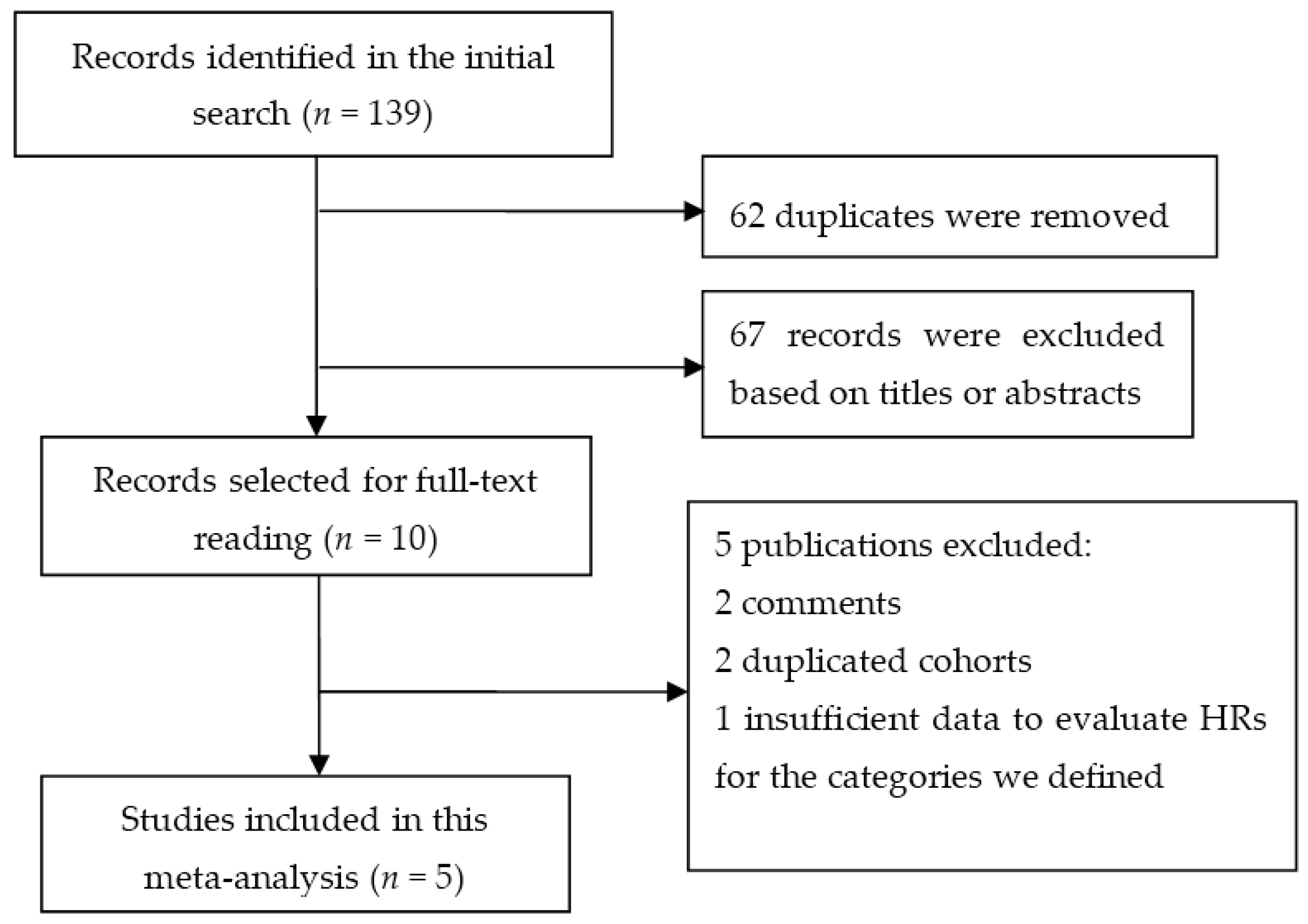

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Study Characteristics

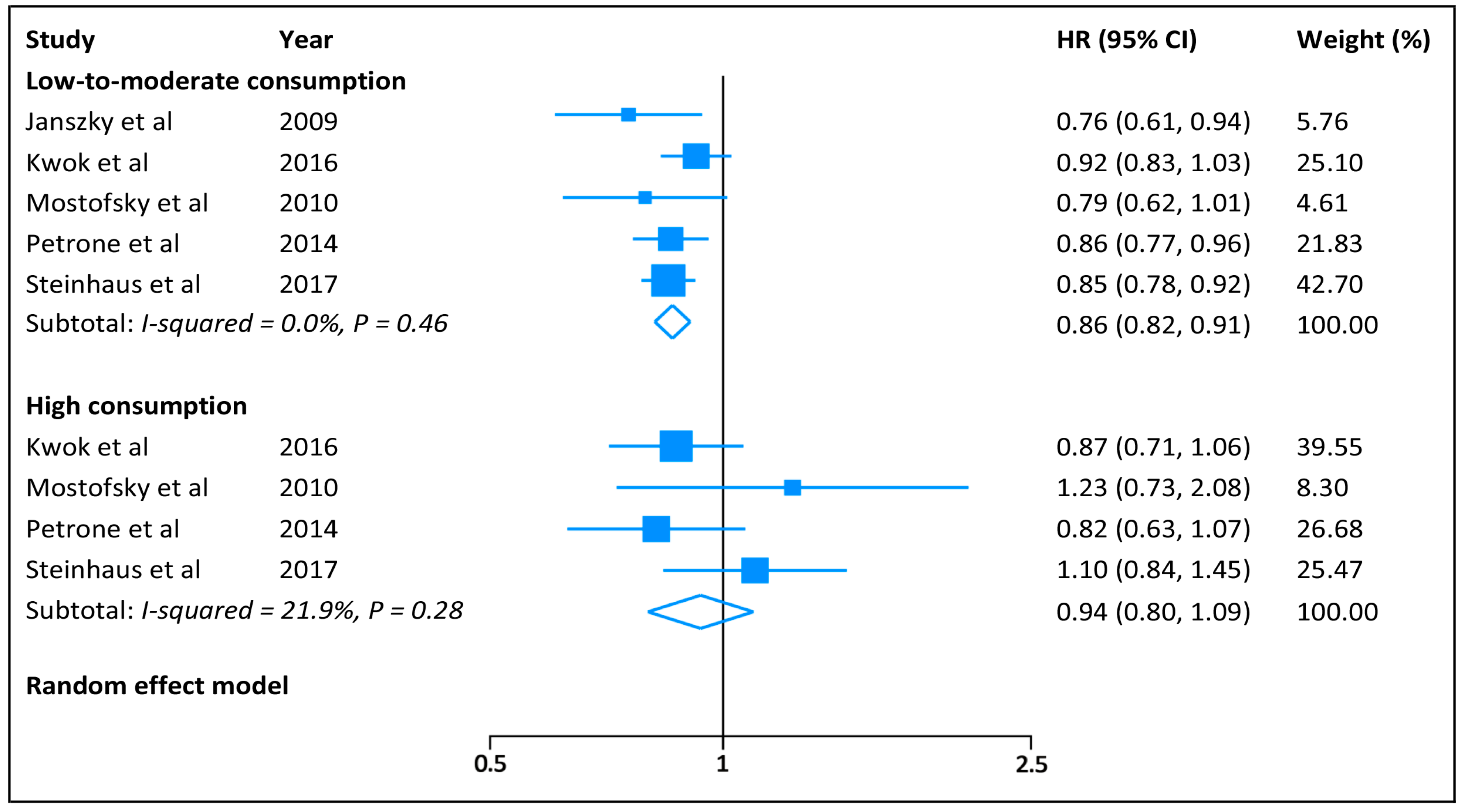

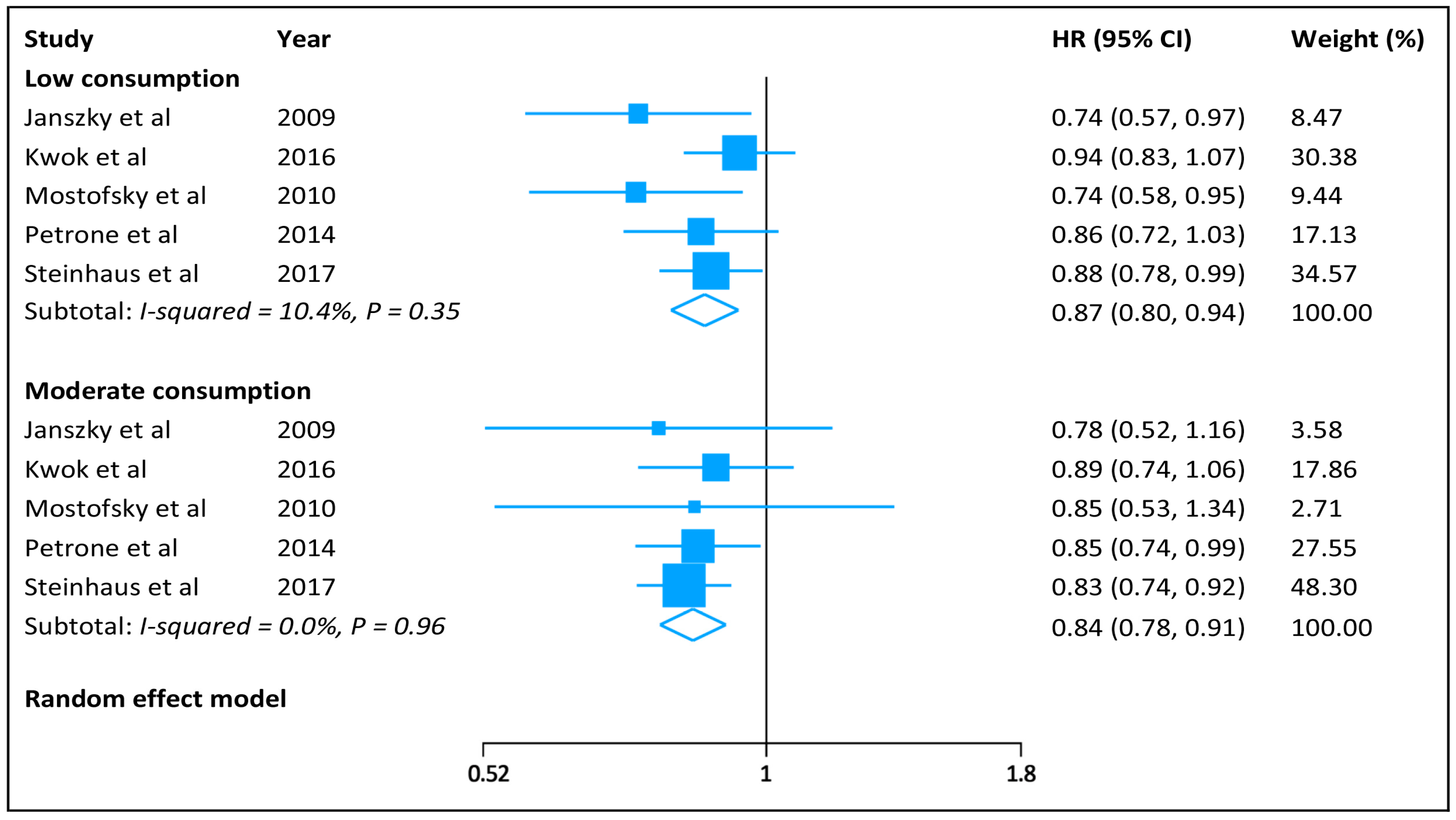

3.3. Categorical Meta-Analysis

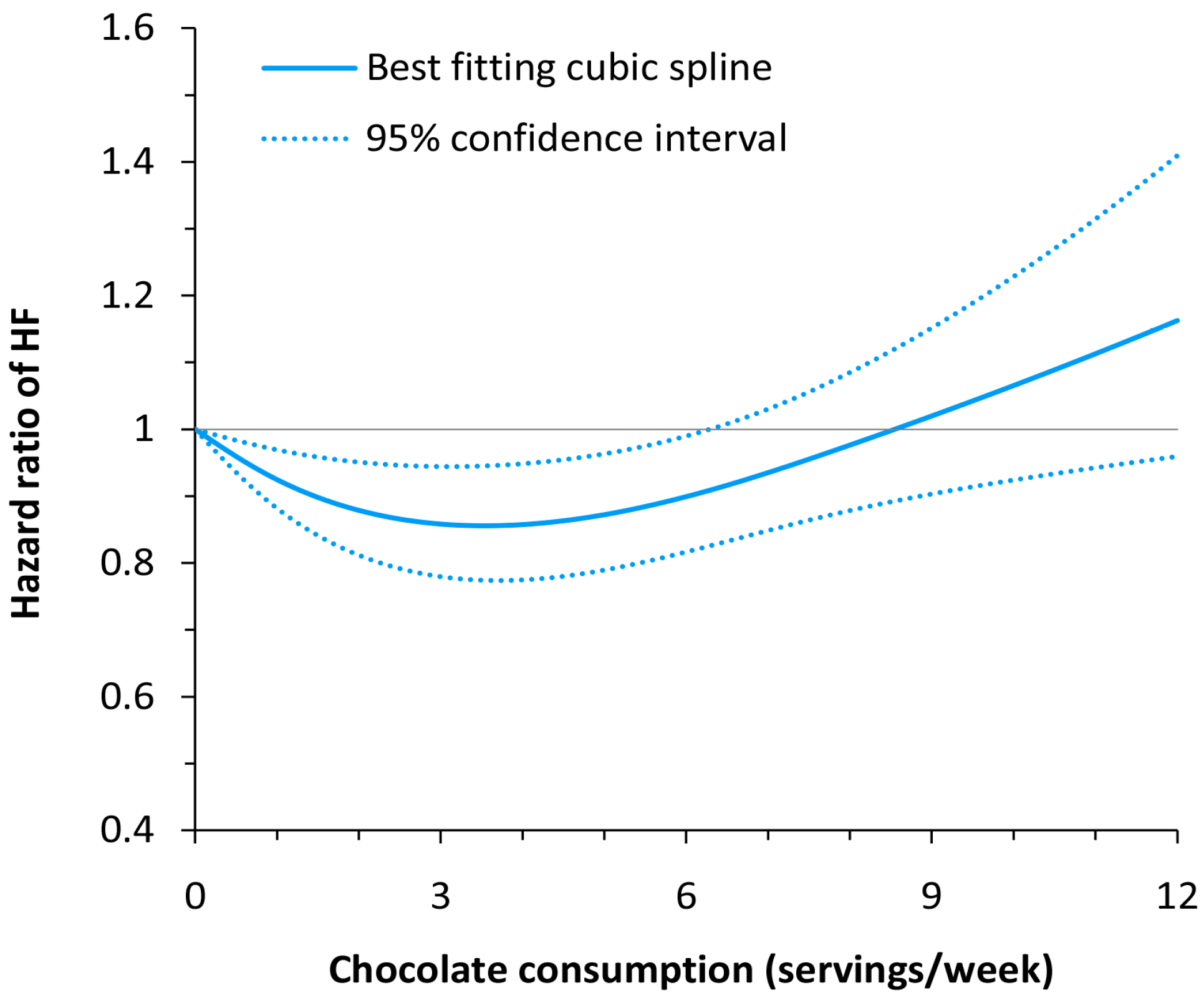

3.4. Dose–response Meta-Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Albert, N.M.; Allen, L.A.; Bluemke, D.A.; Butler, J.; Fonarow, G.C.; Ikonomidis, J.S.; Khavjou, O.; Konstam, M.A.; Maddox, T.M.; et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ. Heart Fail. 2013, 6, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosy, A.P.; Fonarow, G.C.; Butler, J.; Chioncel, O.; Greene, S.J.; Vaduganathan, M.; Nodari, S.; Lam, C.S.; Sato, N.; Shah, A.N.; et al. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: Lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerimi, A.; Williamson, G. The cardiovascular benefits of dark chocolate. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2015, 71, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ried, K.; Sullivan, T.R.; Fakler, P.; Frank, O.R.; Stocks, N.P. Effect of cocoa on blood pressure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, CD008893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijsse, B.; Weikert, C.; Drogan, D.; Bergmann, M.; Boeing, H. Chocolate consumption in relation to blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular disease in German adults. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 1616–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, C.S.; Boekholdt, S.M.; Lentjes, M.A.; Loke, Y.K.; Luben, R.N.; Yeong, J.K.; Wareham, N.J.; Myint, P.K.; Khaw, K.T. Habitual chocolate consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease among healthy men and women. Heart 2015, 101, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flammer, A.J.; Sudano, I.; Wolfrum, M.; Thomas, R.; Enseleit, F.; Periat, D.; Kaiser, P.; Hirt, A.; Hermann, M.; Serafini, M.; et al. Cardiovascular effects of flavanol-rich chocolate in patients with heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 2172–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroup, D.F.; Berlin, J.A.; Morton, S.C.; Olkin, I.; Williamson, G.D.; Rennie, D.; Moher, D.; Becker, B.J.; Sipe, T.A.; Thacker, S.B. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000, 283, 2008–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 21 January 2017).

- Kwok, C.S.; Loke, Y.K.; Welch, A.A.; Luben, R.N.; Lentjes, M.A.; Boekholdt, S.M.; Pfister, R.; Mamas, M.A.; Wareham, N.J.; Khaw, K.T.; et al. Habitual chocolate consumption and the risk of incident heart failure among healthy men and women. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 26, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.R.; Prince, R.L.; Zhu, K.; Devine, A.; Thompson, P.L.; Hodgson, J.M. Habitual chocolate intake and vascular disease: A prospective study of clinical outcomes in older women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 1857–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, S.C.; Orsini, N.; Wolk, A. Alcohol consumption and risk of heart failure: A dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, D.G.; Bland, J.M. Interaction revisited: The difference between two estimates. BMJ 2003, 326, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsini, N.; Li, R.; Wolk, A.; Khudyakov, P.; Spiegelman, D. Meta-analysis for linear and nonlinear dose–response relations: Examples, an evaluation of approximations, and software. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 175, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D.; White, I.R.; Thompson, S.G. Extending DerSimonian and Laird's methodology to perform multivariate random effects meta-analyses. Stat. Med. 2010, 29, 1282–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janszky, I.; Mukamal, K.J.; Ljung, R.; Ahnve, S.; Ahlbom, A.; Hallqvist, J. Chocolate consumption and mortality following a first acute myocardial infarction: The Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program. J. Intern. Med. 2009, 266, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostofsky, E.; Levitan, E.B.; Wolk, A.; Mittleman, M.A. Chocolate intake and incidence of heart failure: A population-based prospective study of middle-aged and elderly women. Circ. Heart Fail. 2010, 3, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrone, A.B.; Gaziano, J.M.; Djousse, L. Chocolate consumption and risk of heart failure in the Physicians’ Health Study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014, 16, 1372–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhaus, D.A.; Mostofsky, E.; Levitan, E.B.; Dorans, K.S.; Hakansson, N.; Wolk, A.; Mittleman, M.A. Chocolate intake and incidence of heart failure: Findings from the Cohort of Swedish Men. Am. Heart J. 2017, 183, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Actis-Goretta, L.; Ottaviani, J.I.; Fraga, C.G. Inhibition of angiotensin converting enzyme activity by flavanol-rich foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, L.; Kay, C.; Abdelhamid, A.; Kroon, P.A.; Cohn, J.S.; Rimm, E.B.; Cassidy, A. Effects of chocolate, cocoa, and flavan-3-ols on cardiovascular health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selmi, C.; Cocchi, C.A.; Lanfredini, M.; Keen, C.L.; Gershwin, M.E. Chocolate at heart: The anti-inflammatory impact of cocoa flavanols. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008, 52, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, G.; Callister, R.; Williamson, G.; Cooper, K.A.; Gleeson, M. The effect of acute pre-exercise dark chocolate consumption on plasma antioxidant status, oxidative stress and immunoendocrine responses to prolonged exercise. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Sanchez, I.; Maya, L.; Ceballos, G.; Villarreal, F. (−)-Epicatechin activation of endothelial cell endothelial nitric oxide synthase, nitric oxide, and related signaling pathways. Hypertension 2010, 55, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado, I.; Castejon, B.; Martin, A.M.; Saura, M.; Reventun-Torralba, P.; Zamorano, J.L.; Zaragoza, C. Nitric oxide induces cardiac protection by preventing extracellular matrix degradation through the complex caveolin-3/EMMPRIN in cardiac myocytes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, J.A.; Manson, J.E.; Buijsse, B.; Wang, L.; Allison, M.A.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Tinker, L.; Waring, M.E.; Isasi, C.R.; Martin, L.W.; et al. Chocolate-candy consumption and 3-year weight gain among postmenopausal U.S. women. Obesity 2015, 23, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.P.; Fonarow, G.C.; Horwich, T.B. Obesity and the obesity paradox in heart failure. Can. J. Cardiol. 2015, 31, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, S.; Lavie, C.J.; Arena, R. Obesity and heart failure: Focus on the obesity paradox. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, S.D.; Ngo, L.; Samelson, E.J.; Kiel, D.P. Competing risk of death: An important consideration in studies of older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Design | Population | Participants (HF/total) | Ascertainments | Location | FU (Years) | Adjustments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | Outcome | |||||||

| Janszky 2009 [16] | Cohort study | Non-diabetic patients with post MI | 279/1169 | Self-reported consumption | ICD-9 and 10 codes | Sweden | 8.7 | Age, sex, smoking, drinking, obesity, physical activity, coffee consumption, educational attainment, and sweet score |

| Kwok 2016 [10] | Cohort study | General population | 1101/20,922 | Food frequency questionnaire | ICD-10 code | UK | 12.5 | Age, sex, education, BMI, social class, physical activity, smoking, drinking, dietary energy, MI, diabetes, arrhythmia, systolic blood pressure, cholesterol level, and heart rate |

| Mostofsky 2010 [17] | Cohort study | Women with no history of diabetes, HF, and MI | 419/31,823 | Food frequency questionnaire | ICD-9 and 10 codes | Sweden | 9 | Age, dietary energy, education, BMI, physical activity, smoking, drinking, living status, postmenopausal hormone use, family history of MI, and hypertension, and high cholesterol |

| Petrone 2014 [18] | Post hoc RCT | Male physicians in the Physician’s Health Study | 876/20,278 | Food frequency questionnaire | Self-reported diagnosis validated by medical records | USA | 9.3 | Age, BMI, smoking, drinking, exercise, dietary energy, and prevalent atrial fibrillation |

| Steinhaus 2017 [19] | Cohort study | Men with no history of diabetes, HF, and MI | 2157/31,917 | Food frequency questionnaire | ICD-9 and 10 codes | Sweden | 14 | Age, dietary energy, DASH diet component score, education, BMI, physical activity, smoking, drinking, family history of MI, hypertension, and high cholesterol |

| Subgroup | Low-to-Moderate Chocolate Consumption | High Chocolate Consumption | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Reports | I2 | HR (95% CI) | p for Interaction | No. of Reports | I2 | HR (95% CI) | p for Interaction | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 3 | 0% | 0.87 (0.82–0.92) | 0.90 | 3 | 18% | 0.93 (0.78–1.09) | 0.88 |

| Women | 2 | 23% | 0.88 (0.75–1.04) | 2 | 35% | 0.96 (0.66–1.39) | ||

| BMI | ||||||||

| <25 Kg/m2 | 3 | 73% | 0.91 (0.74–1.12) | 0.84 | 3 | 54% | 0.87 (0.59–1.28) | 0.77 |

| ≥25 Kg/m2 | 3 | 0% | 0.89 (0.82–0.96) | 3 | 32% | 0.93 (0.74–1.16) | ||

| Prior MI | ||||||||

| No | 4 | 11% | 0.87 (0.82–0.93) | 0.24 | 4 | 18% | 0.94 (0.81–1.10) | 0.55 |

| Yes | 2 | 0% | 0.78 (0.66–0.93) | 1 | - | 0.78 (0.43–1.42) | ||

| Follow-up | ||||||||

| <10 years | 3 | 0% | 0.83 (0.76–0.91) | 0.34 | 2 | 46% | 0.94 (0.65–1.37) | 0.92 |

| ≥10 years | 2 | 23% | 0.88 (0.81–0.95) | 2 | 46% | 0.96 (0.77–1.20) | ||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gong, F.; Yao, S.; Wan, J.; Gan, X. Chocolate Consumption and Risk of Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Nutrients 2017, 9, 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9040402

Gong F, Yao S, Wan J, Gan X. Chocolate Consumption and Risk of Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Nutrients. 2017; 9(4):402. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9040402

Chicago/Turabian StyleGong, Fei, Shuyuan Yao, Jing Wan, and Xuedong Gan. 2017. "Chocolate Consumption and Risk of Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies" Nutrients 9, no. 4: 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9040402

APA StyleGong, F., Yao, S., Wan, J., & Gan, X. (2017). Chocolate Consumption and Risk of Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Nutrients, 9(4), 402. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9040402