Starches, Sugars and Obesity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

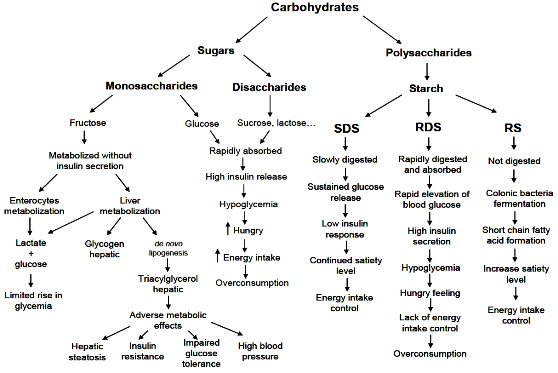

1.1. Classification of Carbohydrates

| Class | Subgroup | Principal components |

|---|---|---|

| Sugars (mono- and disaccharides) | Monosaccharides | Glucose, fructose, galactose |

| Disaccharides | Sucrose, lactose, maltose, trehalose | |

| Sugar-alcohols (polyols) | Sorbitol, mannitol, lactitol, xylitol, erythritol, isomaltitol, maltitol | |

| Oligosaccharides | Maltooligosaccharides (alpha-glucans) | Maltodextrins |

| Non-alpha-glucan oligosaccharides | Raffinose, stachyose, fructo- and galactooligosaccharides, polydextrose, inulin | |

| Polysaccharides | Starch (alpha-glucans) | Amylose, amylopectin, modified starches |

| Non-starch polysaccharides | Cellulose, hemicellulose, pectins, hydrocolloids (e.g., gums, mucilages, beta-glucans) |

1.2. Carbohydrate Digestion

| Type of starch | Example | Probable digestion in the small intestine |

|---|---|---|

| Rapidly digestible starch | Freshly cooked starchy foods | Rapid |

| Slowly digestible starch | Most raw cereals | Slow but complete |

| Resistant starch | ||

| (1) Physically indigestible starch | Partly milled grains and seeds | Resistant |

| (2) Resistant starch granules | Raw potato and banana | Resistant |

| (3) Retrograded starch | Cooled, cooked potato, bread, and cornflakes | Resistant |

1.3. Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load

2. Starches, Obesity and Factors of the Metabolic Syndrome

2.1. Starch Intake, Appetite, Energy Expenditure and Body Weight

2.1.1. Short-Term Effects on Energy Intake and Satiety

2.1.2. Effect on Energy Expenditure

2.1.3. Effect on Body Weight

2.2. Starch Intake and Insulin Resistance

2.3. Starch Intake and Lipids

2.4. Starch Intake and Hormonal Responses

3. Sugars, Obesity and Factors of the Metabolic Syndrome

3.1. Intake of Sugars, Appetite, Energy Expenditure and Body Weight

3.1.1. Sugars, Appetite and Energy Intake

Dissolved vs. Solid Sugars: Effect on Appetite and Energy Intake

3.1.2. Sugars and Energy Expenditure

3.1.3. Sugars, Body Weight and Body Composition

3.1.3.1. Role of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages

3.1.3.2. Dissolved vs. Solid Sugars

3.2. Sugars and Insulin Resistance

3.3. Sugars and Serum Lipids

3.4. Sugars and Blood Pressure

3.5. Intake of Sugars and Hormonal Responses

4. Conclusions

Conflict of Interests

References

- Wiegand, S.; Keller, K.M.; Robl, M.; L’Allemand, D.; Reinehr, T.; Widhalm, K.; Holl, R.W. Obese boys at increased risk for nonalcoholic liver disease: evaluation of 16,390 overweight or obese children and adolescents. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2010, 34, 1468–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deville-Almond, J.; Tahrani, A.A.; Grant, J.; Gray, M.; Thomas, G.N.; Taheri, S. Awareness of Obesity and Diabetes: A Survey of a Subset of British Male Drivers. Am. J. Mens Health 2011, 5, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, H.; Bluher, S.; Falkenberg, C.; Neef, M.; Korner, A.; Wurz, J.; Kiess, W.; Brahler, E. Perception of body weight status: a case control study of obese and lean children and adolescents and their parents. Obes. Facts 2010, 3, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Garaulet, M.; Corbalan-Tutau, M.D.; Madrid, J.A.; Baraza, J.C.; Parnell, L.D.; Lee, Y.C.; Ordovas, J.M. PERIOD2 variants are associated with abdominal obesity, psycho-behavioral factors, and attrition in the dietary treatment of obesity. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chaput, J.P.; Tremblay, A. Obesity and physical inactivity: the relevance of reconsidering the notion of sedentariness. Obes. Facts 2009, 2, 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hamman, R.F.; Wing, R.R.; Edelstein, S.L.; Lachin, J.M.; Bray, G.A.; Delahanty, L.; Hoskin, M.; Kriska, A.M.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Pi-Sunyer, X.; et al. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 2102–2107. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, F.M.; Bray, G.A.; Carey, V.J.; Smith, S.R.; Ryan, D.H.; Anton, S.D.; McManus, K.; Champagne, C.M.; Bishop, L.M.; Laranjo, N.; et al. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 859–873. [Google Scholar]

- Abete, I.; Astrup, A.; Martinez, J.A.; Thorsdottir, I.; Zulet, M.A. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome: role of different dietary macronutrient distribution patterns and specific nutritional components on weight loss and maintenance. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 214–231. [Google Scholar]

- Green, S.M.; Wales, J.K.; Lawton, C.L.; Blundell, J.E. Comparison of high-fat and high-carbohydrate foods in a meal or snack on short-term fat and energy intakes in obese women. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 84, 521–530. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, P. High protein diets and weight control. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2009, 19, 379–382. [Google Scholar]

- Saris, W.H.; Astrup, A.; Prentice, A.M.; Zunft, H.J.; Formiguera, X.; Verboeket-van de Venne, W.P.; Raben, A.; Poppitt, S.D.; Seppelt, B.; Johnston, S.; et al. Randomized controlled trial of changes in dietary carbohydrate/fat ratio and simple vs. complex carbohydrates on body weight and blood lipids: the CARMEN study. The Carbohydrate Ratio Management in European National diets. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2000, 24, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.H.; Stephen, A.M. Carbohydrate terminology and classification. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61 (Suppl. 1), S5–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palou, A.; Bonet, M.L.; Pico, C. On the role and fate of sugars in human nutrition and health. Introduction. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10 (Suppl. 1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wiernsperger, N.; Geloen, A.; Rapin, J.R. Fructose and cardiometabolic disorders: the controversy will, and must, continue. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2010, 65, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Hamaker, B.R. Slowly digestible starch: concept, mechanism, and proposed extended glycemic index. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Englyst, H.N.; Kingman, S.M.; Cummings, J.H. Classification and measurement of nutritionally important starch fractions. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1992, 46 (Suppl. 2), S33–S50. [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee, M. A radical explanation for glucose-induced beta cell dysfunction. J. Clin. Invest. 2003, 112, 1788–1790. [Google Scholar]

- Annison, G.; Topping, D.L. Nutritional role of resistant starch: chemical structure vs. physiological function. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1994, 14, 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Wolever, T.M.; Taylor, R.H.; Barker, H.; Fielden, H.; Baldwin, J.M.; Bowling, A.C.; Newman, H.C.; Jenkins, A.L.; Goff, D.V. Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1981, 34, 362–366. [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Miller, J.; McMillan-Price, J.; Steinbeck, K.; Caterson, I. Dietary glycemic index: health implications. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2009, 28, 446S–449S. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Sofyan, M.; Hamaker, B.R. Slowly digestible state of starch: mechanism of slow digestion property of gelatinized maize starch. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2008, 56, 4695–4702. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, H.J.; Eldridge, A.L.; Beiseigel, J.; Thomas, W.; Slavin, J.L. Greater satiety response with resistant starch and corn bran in human subjects. Nutr. Res. 2009, 29, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bornet, F.R.; Jardy-Gennetier, A.E.; Jacquet, N.; Stowell, J. Glycaemic response to foods: impact on satiety and long-term weight regulation. Appetite 2007, 49, 535–553. [Google Scholar]

- Niwano, Y.; Adachi, T.; Kashimura, J.; Sakata, T.; Sasaki, H.; Sekine, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Yonekubo, A.; Kimura, S. Is glycemic index of food a feasible predictor of appetite, hunger, and satiety? J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo) 2009, 55, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sands, A.L.; Leidy, H.J.; Hamaker, B.R.; Maguire, P.; Campbell, W.W. Consumption of the slow-digesting waxy maize starch leads to blunted plasma glucose and insulin response but does not influence energy expenditure or appetite in humans. Nutr. Res. 2009, 29, 383–390. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, M.; Jensen, M.G.; Riboldi, G.; Petronio, M.; Bugel, S.; Toubro, S.; Tetens, I.; Astrup, A. Wholegrain vs. refined wheat bread and pasta. Effect on postprandial glycemia, appetite, and subsequent ad libitum energy intake in young healthy adults. Appetite 2010, 54, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, N.; Gallaher, D.D.; Arndt, E.A.; Marquart, L. Influence of whole grain barley, whole grain wheat, and refined rice-based foods on short-term satiety and energy intake. Appetite 2009, 53, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aston, L.M.; Stokes, C.S.; Jebb, S.A. No effect of a diet with a reduced glycaemic index on satiety, energy intake and body weight in overweight and obese women. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2008, 32, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champ, M.M. Physiological aspects of resistant starch and in vivo measurements. J. AOAC Int. 2004, 87, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.A.; Higbee, D.R.; Donahoo, W.T.; Brown, I.L.; Bell, M.L.; Bessesen, D.H. Resistant starch consumption promotes lipid oxidation. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.) 2004, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodinham, C.L.; Frost, G.S.; Robertson, M.D. Acute ingestion of resistant starch reduces food intake in healthy adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 917–922. [Google Scholar]

- Raben, A.; Macdonald, I.; Astrup, A. Replacement of dietary fat by sucrose or starch: effects on 14 d ad libitum energy intake, energy expenditure and body weight in formerly obese and never-obese subjects. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1997, 21, 846–859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dulloo, A.G.; Eisa, O.A.; Miller, D.S.; Yudkin, J. A comparative study of the effects of white sugar, unrefined sugar and starch on the efficiency of food utilization and thermogenesis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1985, 42, 214–219. [Google Scholar]

- Heijnen, M.L.; Deurenberg, P.; van Amelsvoort, J.M.; Beynen, A.C. Replacement of digestible by resistant starch lowers diet-induced thermogenesis in healthy men. Br. J. Nutr. 1995, 73, 423–432. [Google Scholar]

- Keogh, J.B.; Lau, C.W.; Noakes, M.; Bowen, J.; Clifton, P.M. Effects of meals with high soluble fibre, high amylose barley variant on glucose, insulin, satiety and thermic effect of food in healthy lean women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arola, L.; Bonet, M.L.; Delzenne, N.; Duggal, M.S.; Gomez-Candela, C.; Huyghebaert, A.; Laville, M.; Lingstrom, P.; Livingstone, B.; Palou, A.; et al. Summary and general conclusions/outcomes on the role and fate of sugars in human nutrition and health. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10 (Suppl. 1), 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Baak, M.A.; Astrup, A. Consumption of sugars and body weight. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10 (Suppl. 1), 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D.E.; Elliott, E.J.; Baur, L. Low glycaemic index or low glycaemic load diets for overweight and obesity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, CD005105. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, T.M.; Dalskov, S.-M.; van Baak, M.; Jebb, S.A.; Papadaki, A.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Martinez, J.A.; Handjieva-Darlenska, T.; Kunešová, M.; Pihlsgård, M.; et al. Diets with High or Low Protein Content and Glycemic Index for Weight-Loss Maintenance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2102–2113. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, D.B.; Kushner, J.A.; Ludwig, D.S. Effects of dietary glycaemic index on adiposity, glucose homoeostasis, and plasma lipids in animals. Lancet 2004, 364, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aziz, A.A.; Kenney, L.S.; Goulet, B.; Abdel-Aal, E.-S. Dietary starch type affects body weight and glycemic control in freely fed but not energy-restricted obese rats. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1881–1889. [Google Scholar]

- Isken, F.; Klaus, S.; Petzke, K.J.; Loddenkemper, C.; Pfeiffer, A.F.; Weickert, M.O. Impairment of fat oxidation under high- vs. low-glycemic index diet occurs before the development of an obese phenotype. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 298, E287–E295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.H.; Cho, C.E.; Akhavan, T.; Mollard, R.C.; Luhovyy, B.L.; Finocchiaro, E.T. Relation between estimates of cornstarch digestibility by the Englyst in vitro method and glycemic response, subjective appetite, and short-term food intake in young men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rave, K.; Roggen, K.; Dellweg, S.; Heise, T.; tom Dieck, H. Improvement of insulin resistance after diet with a whole-grain based dietary product: results of a randomized, controlled cross-over study in obese subjects with elevated fasting blood glucose. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, 929–936. [Google Scholar]

- Ells, L.J.; Seal, C.J.; Kettlitz, B.; Bal, W.; Mathers, J.C. Postprandial glycaemic, lipaemic and haemostatic responses to ingestion of rapidly and slowly digested starches in healthy young women. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 94, 948–955. [Google Scholar]

- Seal, C.J.; Daly, M.E.; Thomas, L.C.; Bal, W.; Birkett, A.M.; Jeffcoat, R.; Mathers, J.C. Postprandial carbohydrate metabolism in healthy subjects and those with type 2 diabetes fed starches with slow and rapid hydrolysis rates determined in vitro. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 90, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikany, J.M.; Phadke, R.P.; Redden, D.T.; Gower, B.A. Effects of low- and high-glycemic index/glycemic load diets on coronary heart disease risk factors in overweight/obese men. Metabolism 2009, 58, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar]

- Granfeldt, Y.; Wu, X.; Bjorck, I. Determination of glycaemic index; some methodological aspects related to the analysis of carbohydrate load and characteristics of the previous evening meal. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liljeberg, H.; Bjorck, I. Effects of a low-glycaemic index spaghetti meal on glucose tolerance and lipaemia at a subsequent meal in healthy subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 54, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Liljeberg, H.G.; Akerberg, A.K.; Bjorck, I.M. Effect of the glycemic index and content of indigestible carbohydrates of cereal-based breakfast meals on glucose tolerance at lunch in healthy subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 647–655. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, A.; Granfeldt, Y.; Ostman, E.; Preston, T.; Bjorck, I. Effects of GI and content of indigestible carbohydrates of cereal-based evening meals on glucose tolerance at a subsequent standardised breakfast. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 1092–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Wolever, T.M.; Taylor, R.H.; Griffiths, C.; Krzeminska, K.; Lawrie, J.A.; Bennett, C.M.; Goff, D.V.; Sarson, D.L.; Bloom, S.R. Slow release dietary carbohydrate improves second meal tolerance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1982, 35, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Trinick, T.R.; Laker, M.F.; Johnston, D.G.; Keir, M.; Buchanan, K.D.; Alberti, K.G. Effect of guar on second-meal glucose tolerance in normal man. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 1986, 71, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, A.C.; Ostman, E.M.; Granfeldt, Y.; Bjorck, I.M. Effect of cereal test breakfasts differing in glycemic index and content of indigestible carbohydrates on daylong glucose tolerance in healthy subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 645–654. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, H.; Frost, G. Glycaemic index, appetite and body weight. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, K.L.; Thomas, E.L.; Bell, J.D.; Frost, G.S.; Robertson, M.D. Resistant starch improves insulin sensitivity in metabolic syndrome. Diabet. Med. 2010, 27, 391–397. [Google Scholar]

- Tarini, J.; Wolever, T.M. The fermentable fibre inulin increases postprandial serum short-chain fatty acids and reduces free-fatty acids and ghrelin in healthy subjects. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 35, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, M.D.; Currie, J.M.; Morgan, L.M.; Jewell, D.P.; Frayn, K.N. Prior short-term consumption of resistant starch enhances postprandial insulin sensitivity in healthy subjects. Diabetologia 2003, 46, 659–665. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, M.D.; Bickerton, A.S.; Dennis, A.L.; Vidal, H.; Frayn, K.N. Insulin-sensitizing effects of dietary resistant starch and effects on skeletal muscle and adipose tissue metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 559–567. [Google Scholar]

- Culling, K.S.; Neil, H.A.; Gilbert, M.; Frayn, K.N. Effects of short-term low- and high-carbohydrate diets on postprandial metabolism in non-diabetic and diabetic subjects. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2009, 19, 345–351. [Google Scholar]

- So, P.W.; Yu, W.S.; Kuo, Y.T.; Wasserfall, C.; Goldstone, A.P.; Bell, J.D.; Frost, G. Impact of resistant starch on body fat patterning and central appetite regulation. PLoS One 2007, 2, e1309. [Google Scholar]

- Brighenti, F.; Benini, L.; Del Rio, D.; Casiraghi, C.; Pellegrini, N.; Scazzina, F.; Jenkins, D.J.; Vantini, I. Colonic fermentation of indigestible carbohydrates contributes to the second-meal effect. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 817–822. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, T.A.; Lyons-Wall, P.; Bremner, A.P.; Ambrosini, G.L.; Huang, R.C.; Beilin, L.J.; Mori, T.A.; Blair, E.; Oddy, W.H. Dietary glycaemic carbohydrate in relation to the metabolic syndrome in adolescents: comparison of different metabolic syndrome definitions. Diabet. Med. 2010, 27, 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Kendall, C.W.; Axelsen, M.; Augustin, L.S.; Vuksan, V. Viscous and nonviscous fibres, nonabsorbable and low glycaemic index carbohydrates, blood lipids and coronary heart disease. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2000, 11, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queenan, K.M.; Stewart, M.L.; Smith, K.N.; Thomas, W.; Fulcher, R.G.; Slavin, J.L. Concentrated oat beta-glucan, a fermentable fiber, lowers serum cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic adults in a randomized controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2007, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandalia, M.; Garg, A.; Lutjohann, D.; von Bergmann, K.; Grundy, S.M.; Brinkley, L.J. Beneficial effects of high dietary fiber intake in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 1392–1398. [Google Scholar]

- Toeller, M.; Buyken, A.E.; Heitkamp, G.; de Pergola, G.; Giorgino, F.; Fuller, J.H. Fiber intake, serum cholesterol levels, and cardiovascular disease in European individuals with type 1 diabetes. EURODIAB IDDM Complications Study Group. Diabetes Care 1999, 22 (Suppl. 2), B21–B28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jarvi, A.E.; Karlstrom, B.E.; Granfeldt, Y.E.; Bjorck, I.E.; Asp, N.G.; Vessby, B.O. Improved glycemic control and lipid profile and normalized fibrinolytic activity on a low-glycemic index diet in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Turley, M.L.; Skeaff, C.M.; Mann, J.I.; Cox, B. The effect of a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet on serum high density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglyceride. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 52, 728–732. [Google Scholar]

- de Deckere, E.A.; Kloots, W.J.; van Amelsvoort, J.M. Resistant starch decreases serum total cholesterol and triacylglycerol concentrations in rats. J. Nutr. 1993, 123, 2142–2151. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi, Y.; Nagaoka, D.; Ishioka, K.; Bigley, K.E.; Okawa, M.; Otsuji, K.; Bauer, J.E. Postprandial Lipid-Related Metabolites Are Altered in Dogs Fed Dietary Diacylglycerol and Low Glycemic Index Starch during Weight Loss. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1815–1823. [Google Scholar]

- Behall, K.M.; Howe, J.C. Effect of long-term consumption of amylose vs. amylopectin starch on metabolic variables in human subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 61, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cummings, D.E.; Foster, K.E. Ghrelin-leptin tango in body-weight regulation. Gastroenterology 2003, 124, 1532–1535. [Google Scholar]

- Ahima, R.S.; Flier, J.S. Leptin. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2000, 62, 413–437. [Google Scholar]

- Pico, C.; Oliver, P.; Sanchez, J.; Palou, A. Gastric leptin: a putative role in the short-term regulation of food intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 90, 735–741. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, D.E.; Purnell, J.Q.; Frayo, R.S.; Schmidova, K.; Wisse, B.E.; Weigle, D.S. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes 2001, 50, 1714–1719. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, J.; Cladera, M.M.; Llopis, M.; Palou, A.; Pico, C. The different satiating capacity of CHO and fats can be mediated by different effects on leptin and ghrelin systems. Behav. Brain Res. 2010, 213, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, A.C.; Ostman, E.M.; Holst, J.J.; Bjorck, I.M. Including indigestible carbohydrates in the evening meal of healthy subjects improves glucose tolerance, lowers inflammatory markers, and increases satiety after a subsequent standardized breakfast. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wachters-Hagedoorn, R.E.; Priebe, M.G.; Heimweg, J.A.; Heiner, A.M.; Englyst, K.N.; Holst, J.J.; Stellaard, F.; Vonk, R.J. The rate of intestinal glucose absorption is correlated with plasma glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide concentrations in healthy men. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1511–1516. [Google Scholar]

- Alvina, M.; Araya, H. Rapid carbohydrate digestion rate produced lesser short-term satiety in obese preschool children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 637–642. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, M.J.; Zhou, J.; McCutcheon, K.L.; Raggio, A.M.; Bateman, H.G.; Todd, E.; Jones, C.K.; Tulley, R.T.; Melton, S.; Martin, R.J.; et al. Effects of resistant starch, a non-digestible fermentable fiber, on reducing body fat. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006, 14, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tappy, L. Thermic effect of food and sympathetic nervous system activity in humans. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 1996, 36, 391–397. [Google Scholar]

- Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Satiety and 24 h diet-induced thermogenesis as related to macronutrient composition. Scand. J. Nutr. 2000, 44, 104–107. [Google Scholar]

- Trumbo, P.; Schlicker, S.; Yates, A.A.; Poos, M. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruxton, C.H.; Gardner, E.J.; McNulty, H.M. Is sugar consumption detrimental to health? A review of the evidence 1995–2006. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for carbohydrates and dietary fibre. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1462–1539.

- Tappy, L.; Le, K.A. Metabolic effects of fructose and the worldwide increase in obesity. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, T.H. Fructose and satiety. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1253S–1256S. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, L.C.; Potter, S.M.; Burdock, G.A. Evidence-based review on the effect of normal dietary consumption of fructose on development of hyperlipidemia and obesity in healthy, normal weight individuals. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, J.; Noakes, M.; Trenerry, C.; Clifton, P.M. Energy intake, ghrelin, and cholecystokinin after different carbohydrate and protein preloads in overweight men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q. Gain weight by “going diet?” Artificial sweeteners and the neurobiology of sugar cravings: Neuroscience 2010. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2010, 83, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- DiMeglio, D.P.; Mattes, R.D. Liquid versus solid carbohydrate: effects on food intake and body weight. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2000, 24, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhavan, T.; Luhovyy, B.L.; Anderson, G.H. Effect of drinking compared with eating sugars or whey protein on short-term appetite and food intake. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappy, L.; Randin, J.P.; Felber, J.P.; Chiolero, R.; Simonson, D.C.; Jequier, E.; DeFronzo, R.A. Comparison of thermogenic effect of fructose and glucose in normal humans. Am. J. Physiol. 1986, 250, E718–E724. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, J.M.; Acheson, K.J.; Tappy, L.; Piolino, V.; Muller, M.J.; Felber, J.P.; Jequier, E. Thermogenesis and fructose metabolism in humans. Am. J. Physiol. 1992, 262, E591–E598. [Google Scholar]

- Brundin, T.; Wahren, J. Whole body and splanchnic oxygen consumption and blood flow after oral ingestion of fructose or glucose. Am. J. Physiol. 1993, 264, E504–E513. [Google Scholar]

- Sharief, N.N.; Macdonald, I. Differences in dietary-induced thermogenesis with various carbohydrates in normal and overweight men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1982, 35, 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Blaak, E.E.; Saris, W.H. Postprandial thermogenesis and substrate utilization after ingestion of different dietary carbohydrates. Metabolism 1996, 45, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar]

- White, C.; Drummond, S.; De Looy, A. Comparing advice to decrease both dietary fat and sucrose, or dietary fat only, on weight loss, weight maintenance and perceived quality of life. Int. J. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2010, 61, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, V.S.; Popkin, B.M.; Bray, G.A.; Despres, J.P.; Hu, F.B. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation 2010, 121, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, S. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks and obesity: a systematic review of the evidence from observational studies and interventions. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2008, 21, 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, E.; Dansinger, M.L. Soft drinks and weight gain: how strong is the link? Medscape J. Med. 2008, 10, 189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olsen, N.J.; Heitmann, B.L. Intake of calorically sweetened beverages and obesity. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Appel, L.J.; Loria, C.; Lin, P.H.; Champagne, C.M.; Elmer, P.J.; Ard, J.D.; Mitchell, D.; Batch, B.C.; Svetkey, L.P.; et al. Reduction in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with weight loss: the PREMIER trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Laville, M.; Nazare, J.A. Diabetes, insulin resistance and sugars. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10 (Suppl. 1), 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, M.; McKeown, N.M.; Rogers, G.; Meigs, J.B.; Saltzman, E.; D’Agostino, R.; Jacques, P.F. Surrogate markers of insulin resistance are associated with consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and fruit juice in middle and older-aged adults. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2121–2127. [Google Scholar]

- Teff, K.L.; Grudziak, J.; Townsend, R.R.; Dunn, T.N.; Grant, R.W.; Adams, S.H.; Keim, N.L.; Cummings, B.P.; Stanhope, K.L.; Havel, P.J. Endocrine and metabolic effects of consuming fructose- and glucose-sweetened beverages with meals in obese men and women: influence of insulin resistance on plasma triglyceride responses. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 1562–1569. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, V.S.; Popkin, B.M.; Bray, G.A.; Despres, J.P.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Sugar Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 2477–2483. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.K.; Appel, L.J.; Brands, M.; Howard, B.V.; Lefevre, M.; Lustig, R.H.; Sacks, F.; Steffen, L.M.; Wylie-Rosett, J. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009, 120, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, E.J.; Gleason, J.A.; Dansinger, M.L. Dietary fructose and glucose differentially affect lipid and glucose homeostasis. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1257S–1262S. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Roberts, L.S.; Lustig, R.H.; Fleming, S.E. Carbohydrate intake and cardiometabolic risk factors in high BMI African American children. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.) 2010, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, J.A.; Sharma, A.; Abramson, J.L.; Vaccarino, V.; Gillespie, C.; Vos, M.B. Caloric sweetener consumption and dyslipidemia among US adults. JAMA 2010, 303, 1490–1497. [Google Scholar]

- Duffey, K.J.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Steffen, L.M.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Popkin, B.M. Drinking caloric beverages increases the risk of adverse cardiometabolic outcomes in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 954–959. [Google Scholar]

- Yudkin, J. Patterns and Trends in Carbohydrate Consumption and Their Relation to Disease. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1964, 23, 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.J.; Segal, M.S.; Sautin, Y.; Nakagawa, T.; Feig, D.I.; Kang, D.H.; Gersch, M.S.; Benner, S.; Sanchez-Lozada, L.G. Potential role of sugar (fructose) in the epidemic of hypertension, obesity and the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, kidney disease, and cardiovascular dise. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 899–906. [Google Scholar]

- Bidwell, A.J.; Holmstrup, M.E.; Doyle, R.P.; Fairchild, T.J. Assessment of endothelial function and blood metabolite status following acute ingestion of a fructose-containing beverage. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 2010, 200, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jalal, D.I.; Smits, G.; Johnson, R.J.; Chonchol, M. Increased fructose associates with elevated blood pressure. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 1543–1549. [Google Scholar]

- Stanhope, K.L.; Havel, P.J. Endocrine and metabolic effects of consuming beverages sweetened with fructose, glucose, sucrose, or high-fructose corn syrup. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 1733S–1737S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindqvist, A.; Baelemans, A.; Erlanson-Albertsson, C. Effects of sucrose, glucose and fructose on peripheral and central appetite signals. Regul. Pept. 2008, 150, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Melanson, K.J.; Angelopoulos, T.J.; Nguyen, V.; Zukley, L.; Lowndes, J.; Rippe, J.M. High-fructose corn syrup, energy intake, and appetite regulation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 1738S–1744S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teff, K.L.; Elliott, S.S.; Tschop, M.; Kieffer, T.J.; Rader, D.; Heiman, M.; Townsend, R.R.; Keim, N.L.; D’Alessio, D.; Havel, P.J. Dietary fructose reduces circulating insulin and leptin, attenuates postprandial suppression of ghrelin, and increases triglycerides in women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 2963–2972. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marckmann, P.; Raben, A.; Astrup, A. Ad libitum intake of low-fat diets rich in either starchy foods or sucrose: effects on blood lipids, factor VII coagulant activity, and fibrinogen. Metabolism 2000, 49, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Aller, E.E.J.G.; Abete, I.; Astrup, A.; Martinez, J.A.; Baak, M.A.v. Starches, Sugars and Obesity. Nutrients 2011, 3, 341-369. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu3030341

Aller EEJG, Abete I, Astrup A, Martinez JA, Baak MAv. Starches, Sugars and Obesity. Nutrients. 2011; 3(3):341-369. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu3030341

Chicago/Turabian StyleAller, Erik E. J. G., Itziar Abete, Arne Astrup, J. Alfredo Martinez, and Marleen A. van Baak. 2011. "Starches, Sugars and Obesity" Nutrients 3, no. 3: 341-369. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu3030341

APA StyleAller, E. E. J. G., Abete, I., Astrup, A., Martinez, J. A., & Baak, M. A. v. (2011). Starches, Sugars and Obesity. Nutrients, 3(3), 341-369. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu3030341