Underutilized but Sustainable: The Case for Fava Beans in the Iberian Peninsula

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

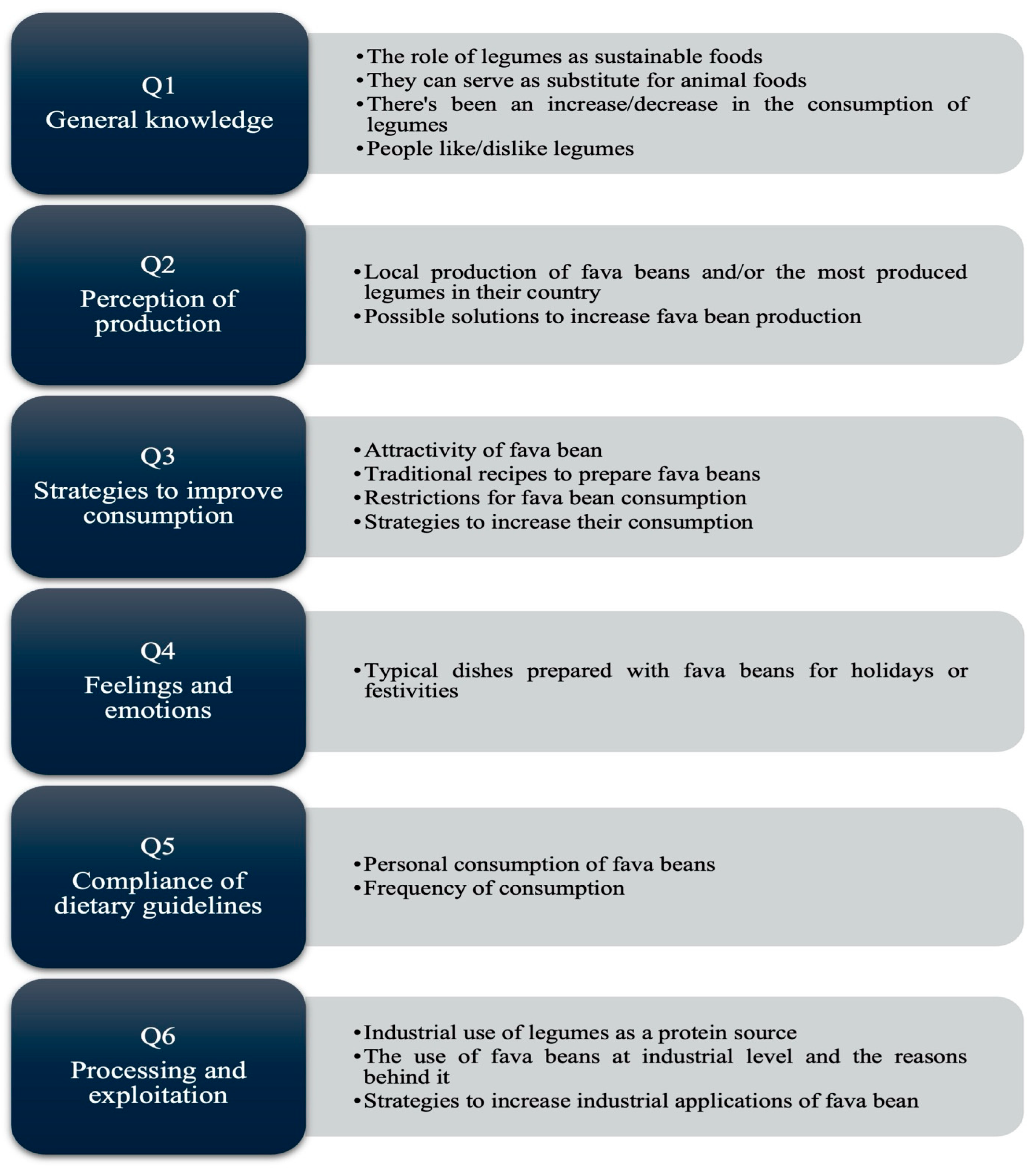

Interview Questions

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographics of Interviewees

3.2. Opinions About Fava Bean Production and Consumption

3.2.1. General Knowledge

3.2.2. Perception of Production

3.2.3. Strategies to Improve Consumption

3.2.4. Feelings and Emotions

3.2.5. Dietary Compliance

3.2.6. Processing and Exploitation

3.3. Strengths and Limitations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hughes, J.; Pearson, E.; Grafenauer, S. Legumes—A Comprehensive Exploration of Global Food-Based Dietary Guidelines and Consumption. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. FAOSTAT Database: Crops and Livestock Products. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Signorelli, S.; Sainz, M.; Tabares-da Rosa, S.; Monza, J. The Role of Nitric Oxide in Nitrogen Fixation by Legumes. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metayer, N. Vicia faba Breeding for Sustainable Agriculture in EUROPE; GIE Féverole, Ed.; EUFABA WP1 Report; GIE Féverole: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Smits, M.; Verhoeckx, K.; Knulst, A.; Welsing, P.; de Jong, A.; Houben, G.; Le, T.-M. Ranking of 10 legumes according to the prevalence of sensitization as a parameter to characterize allergenic proteins. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-M.; Yoon, H.; Shin, M.-J.; Lee, S.; Yi, J.; Jeon, Y.; Wang, X.; Desta, K.T. Nutrient Levels, Bioactive Metabolite Contents, and Antioxidant Capacities of Faba Beans as Affected by Dehulling. Foods 2023, 12, 4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Hong, S.; Li, Y. Pea protein composition, functionality, modification, and food applications: A review. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2022, 101, 135–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Khan, Q.U.; Liu, L.G.; Li, W.; Liu, D.; Haq, I.U. Nutritional composition, health benefits and bio-active compounds of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1218468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beretta, A.; Manuelli, M.; Cena, H. Favism: Clinical Features at Different Ages. Nutrients 2023, 15, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Losito, I.; Facchini, L.; Katina, K.; Palmisano, F.; Gobbetti, M.; Coda, R. Degradation of vicine, convicine and their aglycones during fermentation of faba bean flour. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badjona, A.; Bradshaw, R.; Millman, C.; Howarth, M.; Dubey, B. Faba Bean Processing: Thermal and Non-Thermal Processing on Chemical, Antinutritional Factors, and Pharmacological Properties. Molecules 2023, 28, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharan, S.; Zanghelini, G.; Zotzel, J.; Bonerz, D.; Aschoff, J.; Saint-Eve, A.; Maillard, M. Fava bean (Vicia faba L.) for food applications: From seed to ingredient processing and its effect on functional properties, antinutritional factors, flavor, and color. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 401–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multari, S.; Stewart, D.; Russell, W.R. Potential of Fava Bean as Future Protein Supply to Partially Replace Meat Intake in the Human Diet. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015, 14, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamani, M.H.; Liu, J.; Fitzsimons, S.M.; Fenelon, M.A.; Murphy, E.G. Determining the influence of fava bean pre-processing on extractability and functional quality of protein isolates. Food Chem. X 2024, 21, 101200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-López, I.; Ortiz-Solà, J.; Alamprese, C.; Barros, L.; Shelef, O.; Basheer, L.; Rivera, A.; Abadias, M.; Aguiló-Aguayo, I. Valorization of Local Legumes and Nuts as Key Components of the Mediterranean Diet. Foods 2022, 11, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dernini, S.; Berry, E.; Serra-Majem, L.; La Vecchia, C.; Capone, R.; Medina, F.; Aranceta-Bartrina, J.; Belahsen, R.; Burlingame, B.; Calabrese, G.; et al. Med Diet 4.0: The Mediterranean diet with four sustainable benefits. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Tomaino, L.; Dernini, S.; Berry, E.M.; Lairon, D.; Ngo de la Cruz, J.; Bach-Faig, A.; Donini, L.M.; Medina, F.-X.; Belahsen, R.; et al. Updating the Mediterranean Diet Pyramid towards Sustainability: Focus on Environmental Concerns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, C.L.; Pita, G.; Cavadas, B.; López, S.; Sánchez-Martínez, L.J.; Dugoujon, J.-M.; Novelletto, A.; Cuesta, P.; Pereira, L.; Calderón, R. Human Genomic Diversity Where the Mediterranean Joins the Atlantic. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1041–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Direção-Geral da Saúde. Roda dos Alimentos. Alimentação Saudável. Available online: https://alimentacaosaudavel.dgs.pt/roda-dos-alimentos/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Margara-Escudero, H.J.; Paz-Graniel, I.; García-Gavilán, J.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Sun, Q.; Clish, C.B.; Toledo, E.; Corella, D.; Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; et al. Plasma metabolite profile of legume consumption and future risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Reyes, R.; Furlan, L.C.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Dala-Paula, B.M.; Clerici, M.T.P.S. From ancient crop to modern superfood: Exploring the history, diversity, characteristics, technological applications, and culinary uses of Peruvian fava beans. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenecka, S. Spanish Legumes: The Important Connection Between Provenance and Quality. Foods and Wine from Spain. 2021. Available online: https://www.foodswinesfromspain.com/en/food/articles/2021/may/spanish-legumes-the-important-connection-between-provenance-and-quality. (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación (MAPA). Panel de Consumo Alimentario—Últimos Datos; MAPA: Madrid, Spain, 2023; Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/eu/alimentacion/temas/consumo-tendencias/panel-de-consumo-alimentario/ultimos-datos/default.aspx (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Lopes, C.; Torres, D.; Oliveira, A.; Severo, M.; Alarcão, V.; Guiomar, S.; Mota, J.; Teixeira, P.; Rodrigues, S.; Lobato, L.; et al. Inquérito Alimentar Nacional e de Atividade Física, IAN-AF 2015–2016: Relatório de Resultados; Universidade do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25. EFSA NDA Panel (EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for protein. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.; Vasconcelos, M.; Pinto, E. Pulse Consumption among Portuguese Adults: Potential Drivers and Barriers towards a Sustainable Diet. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key, T.J.; Papier, K.; Tong, T.Y.N. Plant-based diets and long-term health: Findings from the EPIC-Oxford study. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, K.; Tong, T.; Key, T. Dietary Intake of High-Protein Foods and Other Major Foods in Meat-Eaters, Poultry-Eaters, Fish-Eaters, Vegetarians, and Vegans in UK Biobank. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coda, R.; Varis, J.; Verni, M.; Rizzello, C.G.; Katina, K. Improvement of the protein quality of wheat bread through faba bean sourdough addition. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 82, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha do Carmo, C.; Knutsen, S.H.; Malizia, G.; Dessev, T.; Geny, A.; Zobel, H.; Myhrer, K.S.; Varela, P.; Sahlstrøm, S. Meat analogues from a faba bean concentrate can be generated by high moisture extrusion. Future Foods 2021, 3, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, H.; Vasconcelos, M.; Gil, A.M.; Oliveira, B.; Varandas, E.; Vilela, E.; Say, K.; Silveira, J.; Pinto, E. Impact of a daily legume-based meal on dietary and nutritional intake in a group of omnivorous adults. Nutr. Bull. 2023, 48, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázs, B.; Kelemen, E.; Centofanti, T.; Vasconcelos, M.W.; Iannetta, P.P.M. Policy Interventions Promoting Sustainable Food- and Feed-Systems: A Delphi Study of Legume Production and Consumption. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mete, R.; Shield, A.; Murray, K.; Bacon, R.; Kellett, J. What is healthy eating? A qualitative exploration. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2408–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Iskandarova, M.; Hall, J. Industrializing theories: A thematic analysis of conceptual frameworks and typologies for industrial sociotechnical change in a low-carbon future. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 97, 102954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenny, S.; Brannan, J.M.; Brannan, G.D. Qualitative Study. In StatPearls [Internet]; updated January 2025; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470395/ (accessed on 8 February 2025). [PubMed]

- Mason, M. Sample Size and Saturation in PhD Studies Using Qualitative Interviews. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJonckheere, M.; Vaughn, L.M. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Fam. Med. Community Health 2019, 7, e000057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albin, M.Q.; Igihozo, G.; Musemangezhi, S.; Namukanga, E.N.; Uwizeyimana, T.; Alemayehu, G.; Bekele, A.; Wong, R.; Kalinda, C. “When we have served meat, my husband comes first”: A qualitative analysis of child nutrition among urban and rural communities of Rwanda. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neptune, L.; Parsons, K.; McNamara, J. A Qualitative Study of Nutrition Literacy in Undergraduate Students. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa059_055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.V.; Sangeetha, N. Nutritional significance of cereals and legumes based food mix—A review. Int. J. Agric. Life Sci.-IJALS 2017, 3, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, A.; Patil, N.; Bains, A.; Sridhar, K.; Stephen Inbaraj, B.; Tripathi, M.; Chawla, P.; Sharma, M. Recent Trends in Cereal- and Legume-Based Protein-Mineral Complexes: Formulation Methods, Toxicity, and Food Applications. Foods 2023, 12, 3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, F.F.; Ballesteros, J.M.; García-Esquinas, E.; Struijk, E.A.; Ortolá, R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Lopez-Garcia, E. Are legume-based recipes an appropriate source of nutrients for healthy ageing? A prospective cohort study. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 124, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau-Côté, D.; Achouri, A.; Karboune, S.; L’Hocine, L. Faba Bean: An Untapped Source of Quality Plant Proteins and Bioactives. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legume Hub. Faba Bean. Available online: https://legumehub.eu/is_article/the-market-of-grain-legumes-in-spain/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- van Lanen, A.-S.; de Bree, A.; Greyling, A. Efficacy of a low-FODMAP diet in adult irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 3505–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, T.P.; Dalton, L.; Hughes, R.; Jayasinghe, S.; Patterson, K.A.E.; Murray, S.; Soward, R.; Byrne, N.M.; Hills, A.P.; Ahuja, K.D.K. School Gardening and Health and Well-Being of School-Aged Children: A Realist Synthesis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, K.G.; Koch, P.; Contento, I. Implementing and Sustaining School Gardens by Integrating the Curriculum. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2017, 4, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippolis, A.; Roland, W.S.U.; Bocova, O.; Pouvreau, L.; Trindade, L.M. The challenge of breeding for reduced off-flavor in faba bean ingredients. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1286803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, B.; Potente, S.; Rock, V.; McIver, J. Social media campaigns that make a difference: What can public health learn from the corporate sector and other social change marketers? Public Health Res. Pract. 2015, 25, e2521517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunkl, C.; Paudel, R.; Thapa, L.; Tunkl, P.; Jalan, P.; Chandra, A.; Belson, S.; Prasad Gajurel, B.; Haji-Begli, N.; Bajaj, S.; et al. Are digital social media campaigns the key to raise stroke awareness in low-and middle-income countries? A study of feasibility and cost-effectiveness in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulan, I.M.; Popescu, G.; Maștaleru, A.; Oancea, A.; Costache, A.D.; Cojocaru, D.-C.; Cumpăt, C.-M.; Ciuntu, B.M.; Rusu, B.; Leon, M.M. Winter Holidays and Their Impact on Eating Behavior—A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Global Bean Project. Bean Beat—Faba Bean. Available online: https://www.globalbean.eu/publications/faba-bean/ (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Pereira, J.M.; Guedes Melo, R.; de Souza Medeiros, J.; Queiroz de Medeiros, A.C.; de Araújo Lopes, F. Comfort food concepts and contexts in which they are used: A scoping review protocol. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Strien, T.; Gibson, E.L.; Baños, R.; Cebolla, A.; Winkens, L.H.H. Is comfort food actually comforting for emotional eaters? A (moderated) mediation analysis. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 211, 112671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabassa, M.; Hernández Ponce, Y.; Garcia-Ribera, S.; Johnston, B.C.; Salvador Castell, G.; Manera, M.; Pérez Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta-Bartrina, J.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Alonso-Coello, P. Food-based dietary guidelines in Spain: An assessment of their methodological quality. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.; Sørensen, J.C.; Petersen, I.L.; Duque-Estrada, P.; Cappello, C.; Tlais, A.Z.A.; Di Cagno, R.; Ispiryan, L.; Sahin, A.W.; Arendt, E.K.; et al. Associating Compositional, Nutritional and Techno-Functional Characteristics of Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.) Protein Isolates and Their Production Side-Streams with Potential Food Applications. Foods 2023, 12, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhull, S.B.; Kidwai, M.K.; Siddiq, M.; Sidhu, J.S. Faba (Broad) Bean Production, Processing, and Nutritional Profile. In Dry Beans and Pulses; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Identifier | Country | Gender | Age | Stakeholder Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 * | F | 26 | Consumer (<35 years) | |

| P2 * | F | 39 | Consumer (>35 years) | |

| P3 * | F | 43 | R&D at a food company | |

| P4 * | Portugal | F | 26 | Nutritionist |

| P5 * | F | 50 | Farmer | |

| P6 * | F | 32 | Vegetarian | |

| P7 * | F | 31 | Catering nutritionist | |

| S1 ** | F | 28 | Consumer (<35 years) | |

| S2 ** | F | 60 | Consumer (>35 years) | |

| S3 ** | F | 42 | R&D at a food company | |

| S4 ** | Spain | M | 31 | Nutritionist |

| S5 ** | M | 54 | Farmer | |

| S6 ** | F | 31 | Vegetarian | |

| S7 ** | F | 28 | Catering nutritionist |

| Category | Statement |

|---|---|

| Q1 General knowledge | In recent years, much has been said about the role of legumes as healthy and sustainable foods. It has even been proposed that legumes can serve as a substitute for animal foods. In your opinion, have people adhered to these messages, increasing the consumption of legumes? What is your perception of the consumption of legumes in the Portuguese/Spanish population? |

| Q2 Perception of production | Regarding fava bean production, do you know if it’s widely produced in our country? Which are the most produced legumes in Portugal/Spain? In your opinion, what could be done to increase fava bean production in Portugal/Spain? |

| Q3 Strategies to improve consumption | Among legumes, what do you think is the popularity level of fava beans? Is it a legume appreciated by the population? Are there many Portuguese/Spanish recipes prepared with fava beans? In your opinion, what could be done to increase the consumption of fava beans in your country? |

| Q4 Feelings and emotions | Do you know any typical dishes or specialties made with fava beans that are consumed at festive times (e.g., Christmas)? |

| Q5 Dietary compliance (consumption frequency, processing, and exploitation) | Do you usually consume fava beans? If so, how? Can you tell how often you use them? |

| Q6 Processing and exploitation | Some industrialized foods use legume protein as a source of plant protein. Do you have any idea if fava beans are usually used in this type of production? If not, why not? What could be done to increase the use of fava beans as a protein source? |

| Category | Proposal |

|---|---|

| Marketing | Social media campaigns, collaborations with food influencers and chefs, paid advertisements on social media platforms, online recipe sharing. |

| Culinary approach | Develop recipes using novel cooking tools, introducing modern cooking methods, new product development, on-site supermarket advertising and promotion. |

| Education | Implementing school programs on food literacy, integrating fava beans into school gardens and cooking workshops. |

| Scientific improvement | Genetic enhancement of fava beans (with low-tannin varieties) as well as producing more scientific evidence on the nutritional and environmental value of fava beans. |

| Industry support | Increasing supermarket presence, working with retailers to promote fava beans and encourage local farming. |

| Category | Proposal |

|---|---|

| Link to holiday traditions | Leverage the already existing fava bean recipes in Spanish winter dishes (e.g., Caldo de Gloria, winter paella, Galician broth) and incorporate them into Portuguese traditions. |

| Comfort food | Create a focal point on the nostalgic and emotional appeal of fava beans during the cold, winter months. |

| Develop holiday recipes | Modify or improve the already existing festive meals to include fava beans. |

| Create all-year availability | Encourage industrial strategies to preserve fava beans beyond their natural harvest season. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Osorio, J.; Vasconcelos, M.W.; Pinto, E. Underutilized but Sustainable: The Case for Fava Beans in the Iberian Peninsula. Nutrients 2026, 18, 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030510

Osorio J, Vasconcelos MW, Pinto E. Underutilized but Sustainable: The Case for Fava Beans in the Iberian Peninsula. Nutrients. 2026; 18(3):510. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030510

Chicago/Turabian StyleOsorio, Jazmín, Marta W. Vasconcelos, and Elisabete Pinto. 2026. "Underutilized but Sustainable: The Case for Fava Beans in the Iberian Peninsula" Nutrients 18, no. 3: 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030510

APA StyleOsorio, J., Vasconcelos, M. W., & Pinto, E. (2026). Underutilized but Sustainable: The Case for Fava Beans in the Iberian Peninsula. Nutrients, 18(3), 510. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030510