Gut Microbiota and Exercise-Induced Fatigue: A Narrative Review of Mechanisms, Nutritional Interventions, and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

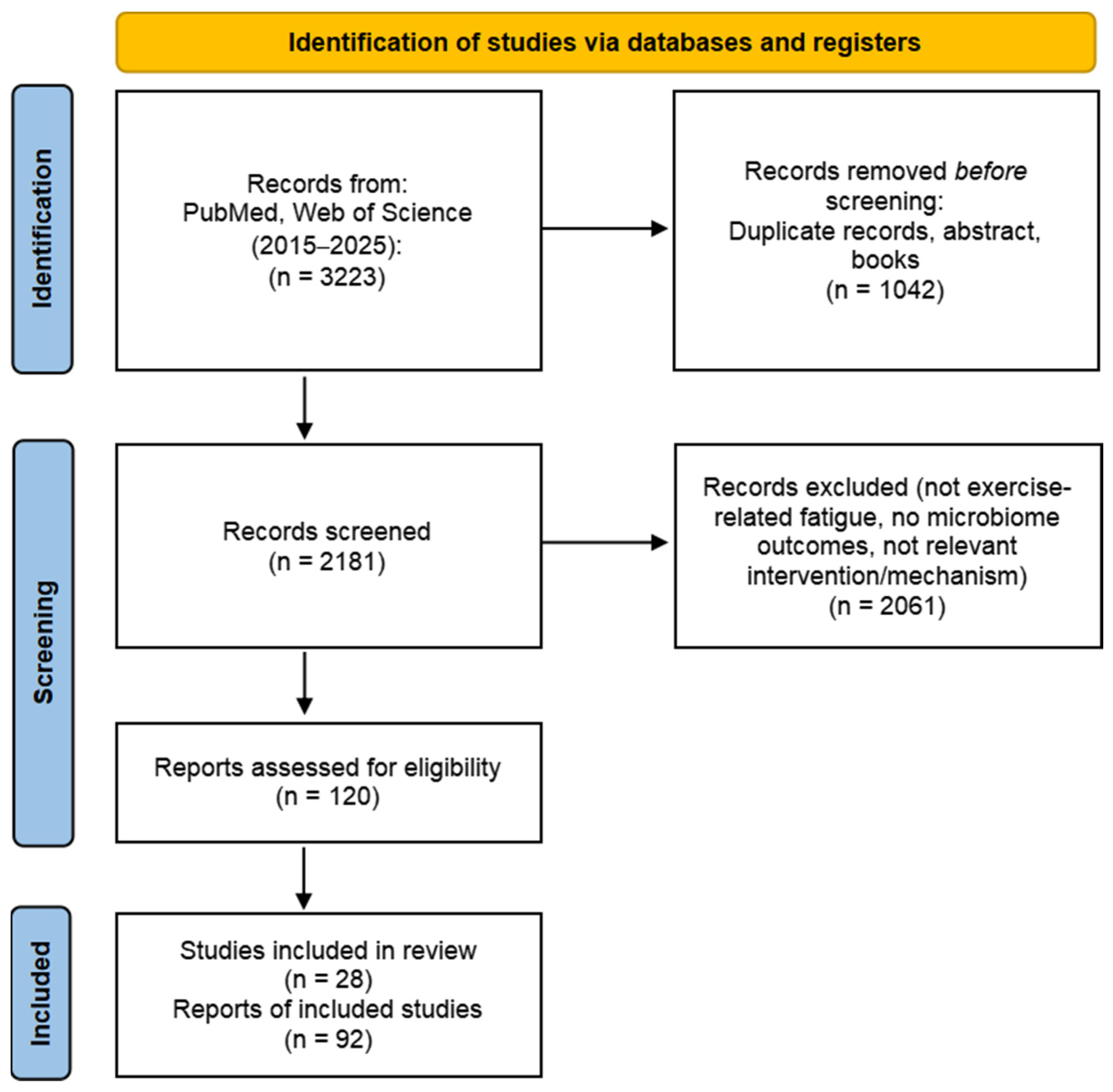

2. Methods

Literature Search Strategy

- PubMed: (fatigue OR “exercise-induced fatigue” OR exhaustion OR overtraining OR recovery) AND (“gut microbiota” OR microbiome OR “intestinal flora” OR dysbiosis) AND (probiotic* OR prebiotic* OR polysaccharide* OR nutrition* OR supplement* OR “dietary intervention”);

- Web of Science: TS = (fatigue OR “exercise-induced fatigue” OR exhaustion OR overtraining OR recovery) AND TS = (“gut microbiota” OR microbiome OR “intestinal flora” OR dysbiosis) AND TS = (probiotic* OR prebiotic* OR polysaccharide* OR nutrition* OR supplement* OR “dietary intervention”).

3. Characteristics of Changes in Gut Microbiota Under Exercise-Induced Fatigue

3.1. Changes in Gut Microbiota Diversity

3.2. Changes in Gut Microbiota Structure

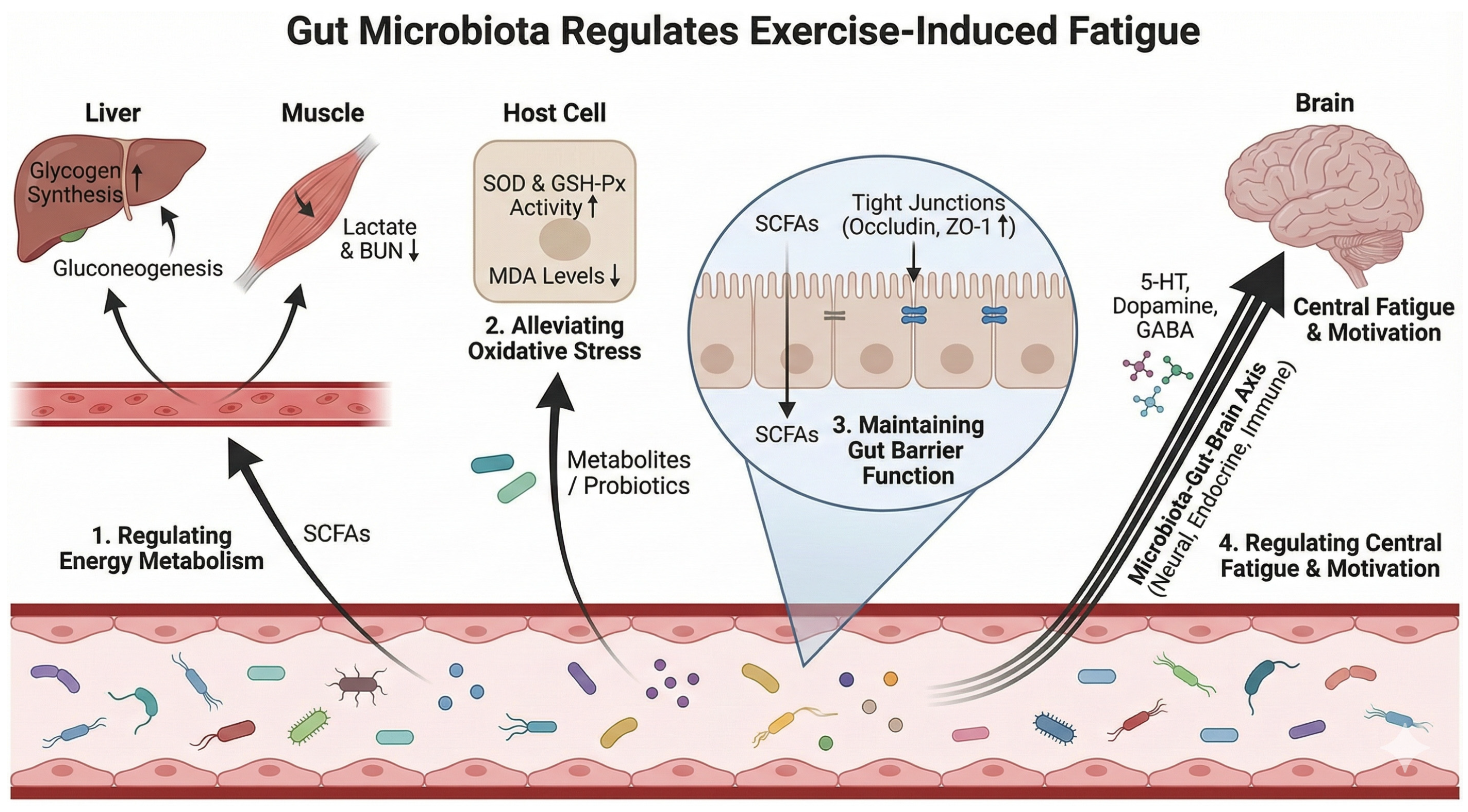

4. The Primary Mechanism of Intestinal Flora Regulating Exercise-Induced Fatigues

4.1. Regulate Energy Metabolism

4.2. Reduce Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Response

4.3. Maintain Intestinal Barrier Function

4.4. Regulation of Central Fatigue and Exercise Motivation

5. Therapeutic Strategies for Modulating the Gut Microbiota to Mitigate Exercise-Induced Fatigue

5.1. Probiotic Interventions

5.2. Plant Polysaccharides and Extracts

5.3. Proteins, Peptides, and Other Nutrients

5.4. Other Intervention Schemes

6. Conclusions and Discussion

7. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Appell, H.J.; Soares, J.M.; Duarte, J.A. Exercise, muscle damage and fatigue. Sports Med. 1992, 13, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halson, S.L.; Jeukendrup, A.E. Does overtraining exist? An analysis of overreaching and overtraining research. Sports Med. 2004, 34, 967–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, P.Y.; Huang, C.L. Research progress on exercise-induced fatigue. Med. J. Chin. People’s Lib. Army 2016, 41, 955–964. [Google Scholar]

- TavaresSilva, E.; de Aquino Lemos, V.; de França, E.; Silvestre, J.; Dos Santos, S.A.; Ravacci, G.R.; ThomatieliSantos, R.V. Protective Effects of Probiotics on Runners’ Mood: Immunometabolic Mechanisms Post-Exercise. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Sun, Y.; Su, R.B. Research progress on the mechanism of exercise-induced fatigue and anti fatigue drugs. Acta Neuropharmacol. Sin. 2025, 15, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Dmytriv, T.R.; Storey, K.B.; Lushchak, V.I. Intestinal barrier permeability: The influence of gut microbiota, nutrition, and exercise. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1380713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohnalová, L.; Lundgren, P.; Carty, J.R.E.; Goldstein, N.; Wenski, S.L.; Nanudorn, P.; Thiengmag, S.; Huang, K.; Litichevskiy, L.; Descamps, H.C.; et al. A microbiome-dependent gut-brain pathway regulates motivation for exercise. Nature 2022, 612, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Yang, F.; Cao, F.; Luo, F.; Lin, Q. Dietary Polysaccharides Exert Anti-Fatigue Functions via the Gut-Muscle Axis: Advances and Prospectives. Foods 2023, 12, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, M.H.; Jin, J.H.; Ding, W.L.; Chen, J.M.; Qin, Y.F.; Chen, J.H. Study of the effect of exercise fatigue on the gut microbiota of boxers. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1531490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Choi, H.S.; Oh, I.; Chung, J.H.; Moon, J.S. Effects of Limosilactobacillus reuteri ID-D01 Probiotic Supplementation on Exercise Performance and Gut Microbiota in Sprague-Dawley Rats. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 3056–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Yan, W.; Sun, X.; Chen, J. The role of exercise-induced short-chain fatty acids in the gut-muscle axis: Implications for sarcopenia prevention and therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1665551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, L.; Xu, J.; Zhou, J.; Kong, M.; Shen, H.; Mao, Q.; Wu, C.; Long, F.; et al. Integrated anti-fatigue effects of polysaccharides and small molecules coexisting in water extracts of ginseng: Gut microbiota-mediated mechanisms. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 337, 118958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Ma, T.; Qu, Y.; Hu, B.; Xie, Y.; Li, Z. Structural characterization and anti-fatigue mechanism based on the gut-muscle axis of a polysaccharide from Zingiber officinale. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, S.F.; Murphy, E.F.; O’Sullivan, O.; Lucey, A.J.; Humphreys, M.; Hogan, A.; Hayes, P.; O’Reilly, M.; Jeffery, I.B.; WoodMartin, R.; et al. Exercise and associated dietary extremes impact on gut microbial diversity. Gut 2014, 63, 1913–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishima, S.; Aoi, W.; Kawamura, A.; Kawase, T.; Takagi, T.; Naito, Y.; Tsukahara, T.; Inoue, R. Intensive, prolonged exercise seemingly causes gut dysbiosis in female endurance runners. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2021, 68, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, R.D., Jr.; Pontefract, B.A.; Mishcon, H.R.; Black, C.A.; Sutton, S.C.; Theberge, C.R. Gut Microbiome: Profound Implications for Diet and Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.P. LIPUS Regulates Gut Microbiota to Improve Skeletal Muscle Function and Mechanism in Exercise-Induced Fatigue Rats. Master’s Thesis, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C.J.; Henry, R.; Snipe, R.M.J.; Costa, R.J.S. Is the gut microbiota bacterial abundance and composition associated with intestinal epithelial injury, systemic inflammatory profile, and gastrointestinal symptoms in response to exertional-heat stress? J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.R.; Yi, D.P. Exploring the mechanism of exercise-induced fatigue based on metabolomics and gut microbiota analysis. Syst. Med. 2023, 8, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne, F.; Gotteland, M.; Gauthier, L.; Zazueta, A.; Pesoa, S.; Navarrete, P.; Balamurugan, R. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio: A Relevant Marker of Gut Dysbiosis in Obese Patients? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Yang, T.; Tian, Z.; Shi, C.; Yan, C.; Li, H.; Du, Y.; Li, G. Progress in the investigation of the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio as a potential pathogenic factor in ulcerative colitis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2025, 74, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T. The effect of sitosterol on gut microbiota and energy metabolism in exercise-induced fatigue rats. Mol. Plant Breed. 2024, 22, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Xu, W.; Liu, R.; Gong, Y.; Li, M. Resveratrol Alleviated Intensive Exercise-Induced Fatigue Involving in Inhibiting Gut Inflammation and Regulating Gut Microbiota. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z. Xiaochaihu Tang may slow down exercise-induced fatigue by regulating gut microbiota. In Proceedings of the 13th National Sports Science Conference (Sports Medicine Branch), Tianjin, China, 3–5 November 2023; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, G.; Liu, H.; Tan, G.; Li, L.; Liu, W.; Li, M. Fermented ginseng leaf enriched with rare ginsenosides relieves exercise-induced fatigue via regulating metabolites of muscular interstitial fluid, satellite cells-mediated muscle repair and gut microbiota. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 83, 104509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Xu, S.; Huang, H.; Liang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Yuan, H.; Zhao, X.; Lai, X.; Hou, S. Influence of excessive exercise on immunity, metabolism, and gut microbial diversity in an overtraining mice model. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28, 1541–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheiman, J.; Luber, J.M.; Chavkin, T.A.; MacDonald, T.; Tung, A.; Pham, L.; Wibowo, M.C.; Wurth, R.C.; Punthambaker, S.; Tierney, B.T.; et al. Meta-omics analysis of elite athletes identifies a performance-enhancing microbe that functions via lactate metabolism. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.G.; Lamb, G.D.; Westerblad, H. Skeletal muscle fatigue: Cellular mechanisms. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 287–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febbraio, M.A.; Dancey, J. Skeletal muscle energy metabolism during prolonged, fatiguing exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999, 87, 2341–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Tian, J.P.; Yan, Z.H.; Zhao, J.X.; Chen, W.; Wang, G. The relieving effect of Lactobacillus plantarum CCFM1280 on exercise-induced fatigue in mice. Food Ferment. Ind. 2024, 50, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Jing, H.Y.; Hu, X.R.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q.; Xu, B.L.; Zuo, T.T.; Wei, F. Exploring the mechanism of ginseng in improving exercise-induced fatigue based on the gut microbiota short chain fatty acid pathway. Mod. Chin. Med. 2024, 26, 1930–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, K.; Burns, J.L.; Monk, J.M. Effect of Short-Chain Fatty Acids on Inflammatory and Metabolic Function in an Obese Skeletal Muscle Cell Culture Model. Nutrients 2024, 16, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lei, H. Alleviating effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus SDSP202418 on exercise-induced fatigue in mice. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1420872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. Impact of Pediococcus pentosaceus YF01 on the exercise capacity of mice through the regulation of oxidative stress and alteration of gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1421209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Shi, C.; Xia, P.; Ning, K.; Xiang, H.; Xie, Q. Fermented Deer Blood Ameliorates Intense Exercise-Induced Fatigue via Modulating Small Intestine Microbiota and Metabolites in Mice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Zhao, L.; Cao, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gu, S. Weizmannia coagulans BC99: A Novel Adjunct to Protein Supplementation for Enhancing Exercise Endurance and Reducing Fatigue. Foods 2025, 14, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, M.B. Reactive Oxygen Species as Agents of Fatigue. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, S.K.; Jackson, M.J. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: Cellular mechanisms and impact on muscle force production. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 1243–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.Y. Periplaneta americana Glycoproteins in Alleviating Exercise-Induced Fatigue Based on Antioxidant and Gut Microbiota Regulation. Master’s Thesis, Dali University, Yunnan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qian, H. Aqueous Extract of Brassica rapa L.’s Impact on Modulating Exercise-Induced Fatigue via Gut-Muscle Axis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, C.L.; Brennan, C.J.; Cresci, G.; Paul, D.; Hull, M.; Fealy, C.E.; Kirwan, J.P. UCC118 supplementation reduces exercise-induced gastrointestinal permeability and remodels the gut microbiome in healthy humans. Physiol. Rep. 2019, 7, e14276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, R.P.; Dooley, J.S.G.; Matthews, M.; McNeilly, A.M. Do probiotics mitigate GI-induced inflammation and perceived fatigue in athletes? A systematic review. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2024, 21, 2388085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Mei, Y. Clostridium butyricum and Chitooligosaccharides in Synbiotic Combination Ameliorate Symptoms in a DSS-Induced Ulcerative Colitis Mouse Model by Modulating Gut Microbiota and Enhancing Intestinal Barrier Function. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0437022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Mao, X.; Li, R.W.; Hou, E.; Wang, Y.; Xue, C.; Tang, Q. Neoagarotetraose protects mice against intense exercise-induced fatigue damage by modulating gut microbial composition and function. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Rezaei, M.J. Plant polysaccharides and antioxidant benefits for exercise performance and gut health: From molecular pathways to clinic. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2025, 480, 2827–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeusen, R.; Watson, P.; Hasegawa, H.; Roelands, B.; Piacentini, M.F. Central fatigue: The serotonin hypothesis and beyond. Sports Med. 2006, 36, 881–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.L.; Amann, M.; Duchateau, J.; Meeusen, R.; Rice, C.L. Neural Contributions to Muscle Fatigue: From the Brain to the Muscle and Back Again. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 2294–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.H. Study on the Alleviation and Mechanism of Sports Fatigue by Lactobacillus plantarum. Master’s Thesis, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L.M.T. Our Mental Health Is Determined by an Intrinsic Interplay between the Central Nervous System, Enteric Nerves, and Gut Microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Ma, B.; Wang, Z.; Wei, B. Gut Microbiota and Exercise: Probiotics to Modify the Composition and Roles of the Gut Microbiota in the Context of 3P Medicine. Microb. Ecol. 2025, 88, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teglas, T.; Radak, Z. Probiotic supplementation for optimizing athletic performance: Current evidence and future perspectives for microbiome-based strategies. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1572687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Liao, Y.; Lee, M.; Cheng, Y.; Chiou, S.; Lin, J.; Huang, C.; Watanabe, K. Different Impacts of Heat-Killed and Viable Lactiplantibacillus plantarum TWK10 on Exercise Performance, Fatigue, Body Composition, and Gut Microbiota in Humans. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Cheng, T.; Lin, P.; Lin, T.; Chou, C.; Chen, C.; Huang, C. Supplementation with Live and Heat-Treated Lacticaseibacillus paracasei NB23 Enhances Endurance and Attenuates Exercise-Induced Fatigue in Mice. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Hsu, Y.; Chen, M.; Kuo, Y.; Lin, J.; Hsu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, C.; Tsai, S.; Hsia, K.; et al. Efficacy of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis LY-66 and Lactobacillus plantarum PL-02 in Enhancing Explosive Strength and Endurance: A Randomized, Double-Blinded Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, S.; Lackie, T.; Miltko, A.; Kearns, Z.C.; Paquette, M.R.; Bloomer, R.J.; Wang, A.; van der Merwe, M. Safety and efficacy of a probiotic cocktail containing P. acidilactici and L. plantarum for gastrointestinal discomfort in endurance runners: Randomized double-blinded crossover clinical trial. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 49, 890–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Chen, C.; Tsai, Y.; Lin, S.; Huang, C.; Hsu, Y. Effects of Levilactobacillus brevis GKEX supplementation on exercise performance and fatigue resistance in mice. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1625645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, D.; Kuwano, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Hara, S.; Uchiyama, Y.; Sugawara, T.; Fujiwara, S.; Rokutan, K.; Nishida, K. Daily intake of Lactobacillus gasseri CP2305 relieves fatigue and stress-related symptoms in male university Ekiden runners: A double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 57, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Feng, Z.; Hu, Y.; Xu, X.; Kuang, T.; Liu, Y. Polysaccharides derived from natural edible and medicinal sources as agents targeting exercise-induced fatigue: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Zhu, S.; Ma, H.; Fu, J.; Li, W.; Xu, R.; Yang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Gao, C.; Zhang, Y.; et al. The Physicochemical Properties and Anti-Fatigue Efficacy of a Polysaccharide-Rich Fraction Derived From Millettia speciosa Champ. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e01744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Yu, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, W.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Zheng, G. Polysaccharides from Millettia speciosa Champ. Ameliorates Excessive Exercise-Induced Fatigue by Regulating Gut Microbiota. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2025, 23, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Ma, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Su, Z.; Peng, T.; et al. Polygonati rhizoma polysaccharides relieve exercise-induced fatigue by regulating gut microbiota. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 107, 105658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, B.; Zhang, M.; Mao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Cui, S. Enhancing the anti-fatigue effect of ginsenoside extract by Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis CCFM1274 fermentation through biotransformation of Rb1, Rb2 and Rc to Rd. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Ma, N.; Zheng, H.; Ma, G.; Zhao, L.; Hu, Q. Tuber indicum polysaccharide relieves fatigue by regulating gut microbiota in mice. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 63, 103580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Wang, M.; Yuan, Y.; Yan, J.; Peng, Y.; Xu, G.; Weng, X. Konjac Glucomannan Counteracted the Side Effects of Excessive Exercise on Gut Microbiome, Endurance, and Strength in an Overtraining Mice Model. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xie, C.; Tian, Z.; Chai, R.; Ren, Y.; Miao, J.; Xu, W.; Chang, S.; Zhao, C. A soluble garlic polysaccharide supplement alleviates fatigue in mice. npj Sci. Food 2024, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhou, J.; Xu, J.; Shen, H.; Kong, M.; Yip, K.; Han, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, J.; Chen, H.; et al. Ginseng ameliorates exercise-induced fatigue potentially by regulating the gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 3954–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, Z.; Yang, X. Ozone treatment regulated the anti-exercise fatigue effect of fresh-cut pitaya polyphenol extracts. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1500681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Gong, Y.; Zheng, L.; Zhao, M. Whey protein hydrolysate enhances exercise endurance, regulates energy metabolism, and attenuates muscle damage in exercise mice. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.; Yi, T.; Kao, Y.; Liu, T.; Tsai, T.; Chen, Y. Dual-Action Grouper Bone and Wakame Hydrolysates Supplement Enhances Exercise Performance and Modulates Gut Microbiota in Mice. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yang, X.; Ma, J.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z. Ethanol extract of propolis relieves exercise-induced fatigue via modulating the metabolites and gut microbiota in mice. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1549913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, Q.; Sharafeldin, S.; Sang, L.; Wang, C.; Xue, Y.; Shen, Q. Moderate Highland Barley Intake Affects Anti-Fatigue Capacity in Mice via Metabolism, Anti-Oxidative Effects and Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2025, 17, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Sun, H.; Lin, D.; Huang, X.; Chen, R.; Li, M.; Huang, J.; Guo, F. Camellia oil exhibits anti-fatigue property by modulating antioxidant capacity, muscle fiber, and gut microbial composition in mice. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 2465–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Zhuang, T.; Li, W.; Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Lyu, R.; Chen, J.; Liu, C. Effects of Time-Restricted Fasting-Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Combination on Exercise Capacity via Mitochondrial Activation and Gut Microbiota Modulation. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Lu, J.; Li, C.; Wen, B.; Chu, W.; Dang, X.; Zhang, Y.; An, G.; Wang, J.; Fan, R.; et al. Hydrogen improves exercise endurance in rats by promoting mitochondrial biogenesis. Genomics 2022, 114, 110523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, M.; Chiaramonte, R.; Testa, G.; Pavone, V. Clinical Effects of L-Carnitine Supplementation on Physical Performance in Healthy Subjects, the Key to Success in Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis from the Rehabilitation Point of View. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2021, 6, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiak, P.; Kowalski, T.; Rębiś, K.; Klusiewicz, A.; Starczewski, M.; Ładyga, M.; Wiecha, S.; Barylski, M.; Poliwczak, A.R.; Wierzbiński, P.; et al. Below or all the way to the peak? Oxygen uptake efficiency slope as the index of cardiorespiratory response to exercise-the NOODLE study. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1348307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasiak, P.; Kowalski, T.; Rębiś, K.; Klusiewicz, A.; Sadowska, D.; Wilk, A.; Wiecha, S.; Barylski, M.; Poliwczak, A.R.; Wierzbiński, P.; et al. Oxygen uptake efficiency plateau is unaffected by fitness level—The NOODLE study. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pathway | Microbial Features/Targets | Key Mediators (Examples) | Fatigue-Relevant Outcomes | Evidence Base | Representative Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy metabolism & metabolite clearance | ↑ SCFA-producing bacteria; probiotic strains (e.g., Lactiplantibacillus plantarum; Lactobacillus rhamnosus SDSP202418; Pediococcus pentosaceus YF01; Weizmannia coagulans BC99); functional shifts supporting glycogen synthesis and lactate handling | SCFAs (acetate/propionate/butyrate); gluconeogenesis/glycogenesis signaling; LDH modulation | ↑ hepatic/muscle glycogen; ↓ serum lactate & BUN; ↓ LDH/CK (when reported); prolonged endurance/exhaustion time | Mainly animal + intervention studies; some mechanistic links | [25,30,31,32,33,34,35,37,38] |

| Oxidative stress & inflammatory regulation | Probiotics/food bioactives restoring microbial homeostasis; reduced pathogenic taxa clusters; improved SCFA output; taxa–inflammation associations in athletes under heat stress | ROS/redox enzymes (SOD, GSH-Px, CAT); lipid peroxidation (MDA); cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, CRP); LPS–TLR4 signaling | ↓ oxidative damage (↓ MDA); ↑ antioxidant enzymes; ↓ systemic inflammation; improved recovery/fatigue biomarkers | Animal intervention + limited human association evidence | [6,20,33,35,39,40,42] |

| Intestinal barrier integrity & endotoxemia risk | Barrier-supportive microbiota; ↑ butyrate producers; suppression of Gram-negative overgrowth (context-dependent); polysaccharides/natural products modulating communities and metabolites | Tight junction proteins (Occludin, ZO-1); SCFAs (butyrate); LPS translocation; NF-κB pathway | ↓ intestinal permeability; ↓ endotoxemia-driven inflammation; improved fatigue tolerance and recovery | Primarily animal + mechanistic; supportive literature on permeability | [6,8,43,44,45,46,47] |

| Central fatigue & exercise motivation (gut–brain axis) | Microbiota-dependent neuromodulatory pathways; taxa influencing neurotransmitter metabolism; microbiome-dependent endocannabinoid signaling activating sensory neurons | Neurotransmitters (5-HT, dopamine, GABA); endocannabinoid metabolites; TRPV1 sensory neurons; nucleus accumbens dopamine signaling | ↑ exercise motivation/capacity; mitigation of CNS-related fatigue symptoms; improved performance via motivational drive | Mechanistic evidence (animal) | [7,48,49,50,51] |

| Bacteria Strain | Subject(s) | Dose | Duration | Changed Abundance of Gut Microbiota | Main Conclusion | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. reuteri ID-D01 | Sprague-Dawley rats | 3.6 × 107, 1.82 × 109 CFU/g | 53 days | Verrucomicrobia, Ruminococcaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Akkermansia spp. ↑ | Enhance endurance, reduce fatigue, modulate gut microbiota, promote SCFA production | [10] |

| L. brevis GKEX | Male ICR mice | 4 × 1011 CFU/g | 28 days | Anaeroplasma, Roseburia, Blautia, Eubacterium, Christensenella minuta ↑ | Improve endurance, regulate lactic acid metabolism, and boost beneficial bacteria | [58] |

| L. rhamnosus SDSP202418 | Kunming mice | 1 × 109 CFU/mL | 3 weeks | Lactobacillus, Alloprevotella, Odoribacter, Prevotellaceae_UCG-001, Alistipes, and Anaeroplasma ↑; Candidatus_Saccharimonas ↓ | Enhance exercise performance/muscle mass, increase beneficial bacteria, improve body composition/gut health | [35] |

| P. pentosaceus YF01 | Male Kunming mice | 1 × 108 CFU/mL | 4 weeks | Lactobacillus, Lachnospiraceae, and Burkholderiales ↑ | Prolong exhaustion time, ameliorate oxidative stress, regulate muscle/liver gene expression, and elevate probiotic abundance | [36] |

| W. coagulans BC99 | Male Kunming mice | 1 × 106, 1 × 107, 1 × 108 CFU/g | 6 weeks | Roseburia, Mucispirillum, Rikenella, Kineothrix ↑ | +Protein: elevate protease activity, antioxidant capacity, microbiota diversity; enhance endurance, reduce fatigue | [38] |

| L. plantarum TWK10 | Healthy men and women | 1 × 1011 CFU/capsule | 6 weeks | Akkermansiaceae, Prevotellaceae ↑ | Viable/heat-inactivated TWK10: improve exercise capacity, anti-fatigue response; viable form: better muscle gain/fat loss, distinct microbiota/metabolic pathway changes | [54] |

| L. salivarius UCC118 | trained endurance athletes | 2 × 108 CFU/capsule | 4 weeks | Roseburia and Lachnospiraceae ↑; Verrucomicrobia ↓ | Attenuate exercise-induced intestinal hyperpermeability | [43] |

| L. gasseri CP2305 | Male university students | 5 × 107 CFU/mL | 12 weeks | Faecalibacterium, Bifidobacterium ↑ | Alleviate fatigue/anxiety/depression, regulate blood hormones, modulate gut microbiota, and prevent stress-induced mitochondrial gene changes | [59], |

| L. lactis subsp. lactis LY-66, L. plantarum PL-02 | Healthy men and women | 7.5 × 109 CFU/sachet | 6 weeks | Lactobacillus, Lachnospiraceae ↑; Sutterella ↓ (PL-02) Ruminococcus, Prevotella copri, Lactococcus lactis ↑ (LY-66) Akkermansia muciniphila ↑ (PL-02 + LY-66) | Enhance exercise performance/muscle mass, increase beneficial bacteria, improve body composition/gut health | [56] |

| Sources | Phytocompounds | Subject(s) | Dose | Duration | Changed Abundance of Gut Microbiota | Main Conclusion | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garlic slices | Garlic polysaccharide (GP) | Male ICR mice | 1.25 and 2.5 g/kg-BW | 7 weeks | Alloprevotella, Muribaculum, Rikenellaceae_RC9, Parabacteroides, Dubosiella and Eubacterium_ventriosum_group ↑; Enterorhabdus and Desulfovibrio ↓ | Via AMPK/PGC-1α pathway: improve exercise fatigue, activate antioxidant capacity, modulate gut microbiota | [67] |

| Polygonati rhizoma | Polygonati rhizoma polysaccharides (PRP) | Male Kunming mice | 250 mg/kg | 7 days | Akkermansia and Lactobacillus ↑; Streptococcus ↓ | Prolong mouse swimming time, improve blood glucose/antioxidant indices, modulate gut microbiota, alleviate EIF | [63] |

| Ginseng leaves | Fermented ginseng leaves | male Sprague-Dawley rats | 50 mg/kg | 4 weeks | Bacteroidaceae, Allobaculum and Akkermansia ↑ | Elevate ginsenosides, improve fatigue-related biomarkers/gut microbiota, promote muscle cell repair | [27,64] |

| Ginseng | water extract of ginseng | male Sprague-Dawley rats | 13 mg/kg | 20 days | X. Eubacterium. _ ruminantium_group, Bifidobacterium and Clostridium_ sensu_stricto_1 ↑ | Promote SCFA production, improve glycogen storage, reduce inflammatory factors, and enhance anti-fatigue capacity | [33] |

| Konjac | Konjac glucomannan | Male C57BL/6 mice | 1.25, 2.50, and 5.00 g/L as drinking water | 42 days | Prevotellaceae_Prevotella, Allobaculum ↑; Bifidobacterium ↓ | High-dose KGM: maintain microbial homeostasis; medium-dose: boost beneficial bacteria/SCFA production, enhance endurance/strength | [66] |

| Tuber indicum | Tuber indicum polysaccharide | Male C57BL/6 mice | 0.1,0.3 and 0.9 g/kg body weight | 40 days | Porphyromonadaceae, Bacteroidaceae and Rikenellaceae ↑; Prevotellaceae, Ruminococcaceae and Helicobacteraceae ↓ | Reduce blood lactic acid, elevate ATPase activity, improve intestinal permeability, and modulate gut microbiota | [65] |

| / | Resveratrol | male ICR mice | 50 mg/kg | 30 days | Megasphaera and Lactobacillus ↑; Brevundimonas diminuta and Coprobacillus ↓ | Prolong mouse endurance swimming time, improve serum indices, enhance intestinal barrier function, and modulate gut microbiota | [25] |

| Ginseng | water extract of ginseng | male Sprague-Dawley rats | 1.42 g/kg | 14 days | Lactobacillus and Bacteroides ↑; Anaerotruncus ↓ | Regulate energy metabolism/antioxidation, ameliorate gut dysbiosis, alleviate EIF | [68] |

| Brassica rapa L. | aqueous extract of Brassica rapa L. (AEB) | male Swiss mice | 0.5 and 1 g/kg body weight | 30 days | Firmicutes ↑; Bacteroides and Proteobacteria ↓; Enterococcus, Sphingomonas, Mucispirillum, Pseudomonas ↓ | Antioxidant effect; regulate energy metabolism/inflammatory response/gut microbiota; and alleviate EIF | [42] |

| Ppitaya | polyphenol extract of pitaya fruit | male C57BL/6 J mice | 200 mg/kg/day | 21 days | Helicobacter pylori, Desulfovibrio and Eubacteria ↓ | Prolong endurance time, enhance antioxidant capacity, regulate basal metabolism, activate PI3K/Akt pathway, improve gut microbial diversity | [69] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Zhao, S.; Li, W.; Lai, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Guan, F.; Liang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L. Gut Microbiota and Exercise-Induced Fatigue: A Narrative Review of Mechanisms, Nutritional Interventions, and Future Directions. Nutrients 2026, 18, 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030502

Zhao Z, Zhao S, Li W, Lai Z, Zhou Y, Guan F, Liang X, Zhang J, Wang L. Gut Microbiota and Exercise-Induced Fatigue: A Narrative Review of Mechanisms, Nutritional Interventions, and Future Directions. Nutrients. 2026; 18(3):502. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030502

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zhengxin, Shengwei Zhao, Wenli Li, Zheng Lai, Yang Zhou, Feng Guan, Xu Liang, Jiawei Zhang, and Linding Wang. 2026. "Gut Microbiota and Exercise-Induced Fatigue: A Narrative Review of Mechanisms, Nutritional Interventions, and Future Directions" Nutrients 18, no. 3: 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030502

APA StyleZhao, Z., Zhao, S., Li, W., Lai, Z., Zhou, Y., Guan, F., Liang, X., Zhang, J., & Wang, L. (2026). Gut Microbiota and Exercise-Induced Fatigue: A Narrative Review of Mechanisms, Nutritional Interventions, and Future Directions. Nutrients, 18(3), 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030502