Association Between Attitude Toward a Healthy Lifestyle, Lifestyle Behaviors, Sociodemographic Characteristics, and Body Mass Index: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

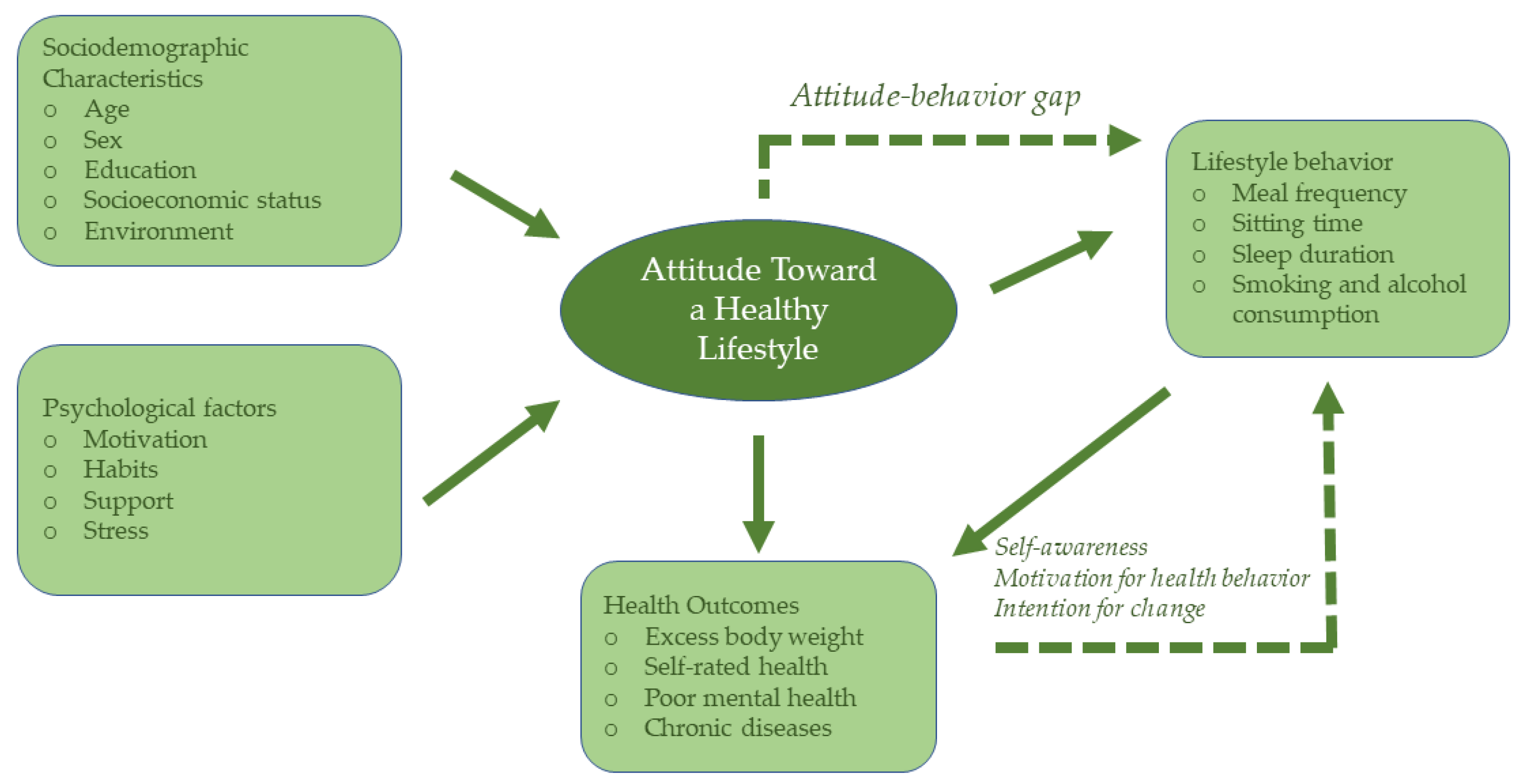

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Attitude Toward a Healthy Lifestyle and Lifestyle Characteristics of Participants

3.3. Differences in Attitude Toward a Healthy Lifestyle and Lifestyle Behaviors According to Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Characteristics

3.4. Associations Between Attitude Toward a Healthy Lifestyle, Lifestyle Behaviors, and BMI

3.5. Associations Between Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors, Excess Body Weight, and Self-Rated Health

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NCDs | Non-communicable diseases |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CVI | Content Validity Index |

| I-CVI | Item-level Content Validity Index |

| S-CVI | Scale-level Content Validity Index |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| β | beta coefficient |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| Mdn | Median |

| N | Number of participants |

| p | p value |

| S.E. | Standard error |

| Wald | Wald test |

References

- Batista, P.; Neves-Amado, J.; Pereira, A.; Amado, J. FANTASTIC Lifestyle Questionnaire from 1983 until 2022: A Review. Health Promot. Perspect. 2023, 13, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Everyday Actions for Better Health—WHO Recommendations. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/everyday-actions-for-better-health-who-recommendations (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- World Health Organization. The Global Status Report on Physical Activity 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/physical-activity/global-status-report-on-physical-activity-2022 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Croatia: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Healthy Living: What Is a Healthy Lifestyle? WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999.

- Schwarzinger, S.; Brenner-Fliesser, M.; Seebauer, S.; Carrus, G.; De Gregorio, E.; Klöckner, C.A.; Pihkola, H. Lifestyle Can Be Anything If Not Defined. A Review of Understanding and Use of the Lifestyle Concept in Sustainability Studies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaman, R.; Hankir, A.; Jemni, M. Lifestyle Factors and Mental Health. Psychiatr. Danub. 2019, 31, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kelly, M.P.; Barker, M. Why Is Changing Health-Related Behaviour so Difficult? Public Health 2016, 136, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, H.; Chaves, I. Effects of Healthy Lifestyles on Chronic Diseases: Diet, Sleep and Exercise. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzate-Mejia, R.G.; Carullo, N.V.N.; Mansuy, I.M. The Epigenome under Pressure: On Regulatory Adaptation to Chronic Stress in the Brain. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2024, 84, 102832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antza, C.; Kostopoulos, G.; Mostafa, S.; Nirantharakumar, K.; Tahrani, A. The Links between Sleep Duration, Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 252, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Lee, D.-B.; Yoon, D.-W.; Yoo, S.-L.; Kim, J. The Effect of Sleep Disruption on Cardiometabolic Health. Life 2025, 15, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chen, Q.; Pu, Y.; Guo, M.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, W.; Long, Y.; Xu, Y. Skipping Breakfast Is Associated with Overweight and Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boushey, C.; Ard, J.; Bazzano, L.; Heymsfield, S.; Mayer-Davis, E.; Sabaté, J.; Snetselaar, L.; Van Horn, L.; Schneeman, B.; English, L.K.; et al. What Is the Relationship between Dietary Patterns Consumed and Growth, Size, Body Composition, and/or Risk of Overweight or Obesity? In Dietary Patterns and Growth, Size, Body Composition, and/or Risk of Overweight or Obesity: A Systematic Review; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK577625/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Xu, X.; Mishra, G.D.; Holt-Lunstad, J.; Jones, M. Social Relationship Satisfaction and Accumulation of Chronic Conditions and Multimorbidity: A National Cohort of Australian Women. Gen. Psychiatry 2023, 36, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haapasalo, V.; de Vries, H.; Vandelanotte, C.; Rosenkranz, R.R.; Duncan, M.J. Cross-Sectional Associations between Multiple Lifestyle Behaviours and Excellent Well-Being in Australian Adults. Prev. Med. 2018, 116, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, A.; Kunzova, S.; Medina-Inojosa, J.R.; Agodi, A.; Barchitta, M.; Homolka, M.; Kiacova, N.; Bauerova, H.; Sochor, O.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; et al. Association between Eating Time Interval and Frequency with Ideal Cardiovascular Health: Results from a Random Sample Czech Urban Population. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, D.; Nóbrega, C.; Manco, L.; Padez, C. The Contribution of Genetics and Environment to Obesity. Br. Med. Bull. 2017, 123, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljubičić, M.; Matek Sarić, M.; Sorić, T.; Sarić, A.; Klarin, I.; Dželalija, B.; Medić, A.; Dilber, I.; Rumbak, I.; Ranilović, J.; et al. The Interplay between Body Mass Index, Motivation for Food Consumption, and Noncommunicable Diseases in the European Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0322454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, M.L. Lifestyle Factors and Genetic Variants Associated to Health Disparities in the Hispanic Population. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Determinants of Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/determinants-of-health (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Chai, X.; Tan, Y.; Dong, Y. An Investigation into Social Determinants of Health Lifestyles of Canadians: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study on Smoking, Physical Activity, and Alcohol Consumption. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.; Stringhini, S.; Vollenweider, P.; Waeber, G.; Marques-Vidal, P. Socio-Demographic and Behavioural Determinants of Weight Gain in the Swiss Population. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sialino, L.D.; Picavet, H.S.J.; Wijnhoven, H.A.H.; Loyen, A.; Verschuren, W.M.M.; Visser, M.; Schaap, L.S.; van Oostrom, S.H. Exploring the Difference between Men and Women in Physical Functioning: How Do Sociodemographic, Lifestyle- and Health-Related Determinants Contribute? BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzadi, S.; Borzu, Z.A.; Jahanfar, S.; Alvani, S.; Balouchi, M.; Gerow, H.J.; Zarvekanloo, S.; Seraj, F. A Comparative Study of Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors and Related Factors among Iranian Male and Female Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorini, S.; Camajani, E.; Cava, E.; Feraco, A.; Armani, A.; Amoah, I.; Filardi, T.; Wu, X.; Strollo, R.; Caprio, M.; et al. Gender Differences in Eating Habits and Sports Preferences across Age Groups: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskeläinen, T.; Koponen, P.; Lundqvist, A.; Koskinen, S. Lifestyle Factors and Obesity in Young Adults—Changes in the 2000s in Finland. Scand. J. Public Health 2022, 50, 1214–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.Y.C.; Ou, K.; Chung, P.K.; Wong, M.Y.C.; Ou, K.; Chung, P.K. Healthy Lifestyle Behavior, Goal Setting, and Personality among Older Adults: A Synthesis of Literature Reviews and Interviews. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozłowska, K.; Ska Szczeci, A.; Roszkowski, W.; Brzozowska, A.; Alfonso, C.; Fjellstrom, C.; Morais, C.; Nielsen, N.A.; Pfau, C.; Saba, A.; et al. Patterns of Healthy Lifestyle and Positive Health Attitudes in Older Europeans. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2008, 12, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maryam, S.; Nor, M.; Abdullah, H.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Munira, W.; Jaafar, W.; Osman, S. The Influence of Healthy Lifestyle Attitude, Subjective Norm, and Perceived Behavioural Control on Healthy Lifestyle Behaviour among Married Individuals in Malaysia: Exploring the Mediating Role of Healthy Lifestyle Intention. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2023, 13, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z. Sex Differences in Association of Healthy Eating Pattern with All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Mortality. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnerud Korslund, S.; Hansen, B.H.; Bjørkkjær, T. Association between Sociodemographic Determinants and Health Behaviors, and Clustering of Health Risk Behaviors among 28,047 Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study among Adults from the General Norwegian Population. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubičić, M.; Baković, L.; Ćoza, M.; Pribisalić, A.; Kolčić, I. Awakening Cortisol Indicators, Advanced Glycation End Products, Stress Perception, Depression and Anxiety in Parents of Children with Chronic Conditions. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 117, 104709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubičić, M.; Šare, S.; Kolčić, I. Sleep Quality and Evening Salivary Cortisol Levels in Association with the Psychological Resources of Parents of Children with Developmental Disorders and Type 1 Diabetes. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024, 55, 1481–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubičić, M.; Delin, S.; Kolčić, I. Family and Individual Quality of Life in Parents of Children with Developmental Disorders and Diabetes Type 1. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Orbell, S. Attitudes, Habits, and Behavior Change. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 73, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, G.A.; Cosci, F.; Sonino, N.; Guidi, J. Understanding Health Attitudes and Behavior. Am. J. Med. 2023, 136, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebede, T.; Taddese, Z.; Girma, A. Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Lifestyle Modification and Associated Factors among Hypertensive Patients on-Treatment Follow up at Yekatit 12 General Hospital in the Largest City of East Africa: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siu, K.; Martinez Leal, I.; Heredia, N.I.; Foreman, J.T.; Hwang, J.P. Lifestyle Attitudes and Habits in a Case Series of Patients With Cancer and Metabolic Syndrome. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2025, 19, 15598276251319262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekelund, U.; Tarp, J.; Ding, D.; Sanchez-Lastra, M.A.; Dalene, K.E.; Anderssen, S.A.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Hansen, B.H.; Morseth, B.; Hopstock, L.A.; et al. Deaths Potentially Averted by Small Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Time: An Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Lancet 2026, 407, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubičić, M.; Matek Sarić, M.; Klarin, I.; Rumbak, I.; Colić Barić, I.; Ranilović, J.; Dželalija, B.; Sarić, A.; Nakić, D.; Djekic, I.; et al. Emotions and Food Consumption: Emotional Eating Behavior in a European Population. Foods 2023, 12, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubičić, M.; Matek Sarić, M.; Klarin, I.; Rumbak, I.; Colić Barić, I.; Ranilović, J.; EL-Kenawy, A.; Papageorgiou, M.; Vittadini, E.; Bizjak, M.Č.; et al. Motivation for Health Behaviour: A Predictor of Adherence to Balanced and Healthy Food across Different Coastal Mediterranean Countries. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 91, 105018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Selected Recent Advances and Applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyafei, A.; Easton-Carr, R. The Health Belief Model of Behavior Change. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC: Tampa, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Raosoft, Inc. Sample Size Calculator by Raosoft, Inc. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Zierle-Ghosh, A.; Jan, A. Physiology, Body Mass Index. In StatPearls; Tampa, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fayyaz, K.; Bataineh, M.F.; Ali, H.I.; Al-Nawaiseh, A.M.; Al-Rifai’, R.H.; Shahbaz, H.M. Validity of Measured vs. Self-Reported Weight and Height and Practical Considerations for Enhancing Reliability in Clinical and Epidemiological Studies: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Body Mass Index (BMI). Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/body-mass-index (accessed on 21 January 2026).

- Bombak, A.E. Self-Rated Health and Public Health: A Critical Perspective. Front. Public Health 2013, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazyar, M.; Kakaei, H.; Azadi, H.; Jalilian, M.; Mansournia, M.A.; Malekan, K.; Pakzad, R. Self-Rated Health Status and Associated Factors in Ilam, West of Iran: Results of a Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1435687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamplova, D.; Klusacek, J.; Mracek, T. Assessment of Self-Rated Health: The Relative Importance of Physiological, Mental, and Socioeconomic Factors. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The Content Validity Index: Are You Sure You Know What’s Being Reported? Critique and Recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendel, K.R.; Vaughan, E.; Kirschmann, J.M.; Johnston, C.A. Moving Beyond Raising Awareness: Addressing Barriers. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2024, 18, 740–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deslippe, A.L.; Soanes, A.; Bouchaud, C.C.; Beckenstein, H.; Slim, M.; Plourde, H.; Cohen, T.R. Barriers and Facilitators to Diet, Physical Activity and Lifestyle Behavior Intervention Adherence: A Qualitative Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naaz, S. Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Pertaining to Healthy Lifestyle in Prevention and Control of Chronic Diseases: A Rapid Review. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2021, 8, 5106–5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutin, I. Body Mass Index Is Just a Number: Conflating Riskiness and Unhealthiness in Discourse on Body Size. Sociol. Health Illn. 2021, 43, 1437–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdeniz Kudubes, A.; Ayar, D.; Bektas, İ.; Bektas, M. Predicting the Effect of Healthy Lifestyle Belief on Attitude toward Nutrition, Exercise, Physical Activity, and Weight-Related Self-Efficacy in Turkish Adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. 2022, 29, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picca, A.; Calvani, R.; Coelho-Júnior, H.J.; Landi, F.; Marzetti, E. Anorexia of Aging: Metabolic Changes and Biomarker Discovery. Clin. Interv. Aging 2022, 17, 1761–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.K.; Jensen, M.D. Metabolic Changes in Aging Humans: Current Evidence and Therapeutic Strategies. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e158451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, M.B.d.A.; Lima, M.G.; Ceolim, M.F.; Zancanella, E.; Cardoso, T.A.M.d.O. Quality of Sleep, Health and Well-Being in a Population-Based Study. Rev. Saude Publica 2019, 53, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Nicolas, A.; Madrid, J.A.; García, F.J.; Campos, M.; Moreno-Casbas, M.T.; Almaida-Pagán, P.F.; Lucas-Sánchez, A.; Rol, M.A. Circadian Monitoring as an Aging Predictor. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Vgontzas, A.N.; Basta, M.; Chen, B.; Xu, C.; Tang, X. Sleep Duration and Metabolic Syndrome: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 59, 101451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliga, E.; Cieśla, E.; Rębak, D.; Kozieł, D.; Głuszek, S. Relationship Between Sitting Time, Physical Activity, and Metabolic Syndrome Among Adults Depending on Body Mass Index (BMI). Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 7633–7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhulaifi, F.; Darkoh, C. Meal Timing, Meal Frequency and Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, G.S.; Vallim, J.R.d.S.; Marques, C.G.; Thomatieli-Santos, R.V.; Jahrami, H.; Vazquez, D.G.; Tufik, S.; Pires, G.N.; D’Almeida, V. Effects of Time Restricted Feeding on Sleep: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chronobiol. Int. 2025, 42, 1744–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.M.; Li, H.J.; Fan, Q.; Xue, Y.D.; Wang, T. Chronobiological Perspectives: Association between Meal Timing and Sleep Quality. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Onge, M.P.; Mikic, A.; Pietrolungo, C.E. Effects of Diet on Sleep Quality. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashatah, A.; Ali, W.S.; Al-Rawi, M.B.A. Attitudes towards Exercise, Leisure Activities, and Sedentary Behavior among Adults: A Cross-Sectional, Community-Based Study in Saudi Arabia. Medicina 2023, 59, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, N.; Healy, G.N.; Matthews, C.E.; Dunstan, D.W. Too Much Sitting: The Population Health Science of Sedentary Behavior. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2010, 38, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Saunders, T.J.; Carson, V.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Chastin, S.F.M.; Altenburg, T.M.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; Aminian, S.; et al. SBRN Terminology Consensus Project Participants. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN) -Terminology Consensus Project Process and Outcome. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, S.; Woo, S.; Webster-Dekker, K.; Chen, W.; Veliz, P.; Larson, J.L. Sedentary Behaviors and Physical Activity of the Working Population Measured by Accelerometry: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, S.; Straker, L. The Contribution of Office Work to Sedentary Behaviour Associated Risk. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, T.D.; Pettee Gabriel, K.; Siddique, J.; Aaby, D.; Whitaker, K.M.; Lane-Cordova, A.; Sidney, S.; Sternfield, B.; Barone Gibbs, B. Sedentary Time and Physical Activity Across Occupational Classifications. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020, 34, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Roundtable on Obesity Solutions. The Science, Strengths, and Limitations of Body Mass Index. In Translating Knowledge of Foundational Drivers of Obesity into Practice: Proceedings of a Workshop Series; Callahan, E., Ed.; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- González-Gálvez, N.; López-Martínez, A.B.; López-Vivancos, A.; González-Gálvez, N.; López-Martínez, A.B.; López-Vivancos, A. Clustered Cardiometabolic Risk and the “Fat but Fit Paradox” in Adolescents: Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparks, J.R.; Wang, X.; Lavie, C.J.; Sui, X. Physical Activity, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, and the Obesity Paradox with Consideration for Racial and/or Ethnic Differences: A Broad Review and Call to Action. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 25, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.M.; Lee, D.H.; Rezende, L.F.M.; Giovannucci, E.L. Different Correlation of Body Mass Index with Body Fatness and Obesity-Related Biomarker According to Age, Sex and Race-Ethnicity. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasco, J.A.; Nicholson, G.C.; Brennan, S.L.; Kotowicz, M.A. Prevalence of Obesity and the Relationship between the Body Mass Index and Body Fat: Cross-Sectional, Population-Based Data. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Mousavi, M.; Azizi, F.; Ramezani Tehrani, F. The Relationship of Reproductive Factors with Adiposity and Body Shape Indices Changes Overtime: Findings from a Community-Based Study. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, B.M.; Berry, D.C. The Regulation of Adipose Tissue Health by Estrogens. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 889923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szałajko, M.; Stachowicz, W.; Dobosz, M.; Szałankiewicz, M.; Sokal, A.; Łuszczki, E. Nutrition Habits and Frequency of Consumption of Selected Food Products by the Residents of Urban and Rural Area from the Subcarpathian Voivodeship. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2021, 72, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabdi, S.; Boujraf, S.; Benzagmout, M. Evaluation of Rural-Urban Patterns in Dietary Intake: A Descriptive Analytical Study—Case Series. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 84, 104972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubičić, M.; Matek Sarić, M.; Barić, I.C.; Rumbak, I.; Komes, D.; Šatalić, Z.; Guiné, R.P.F. Consumer Knowledge and Attitudes toward Healthy Eating in Croatia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2017, 68, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, S.M.; Al-Janabi, A.; Abouelmagd, M.E.; Habib, O.; Abdi, S.M.; Zainab, M.; Hassan, N.A. Eating Behaviors and Nutritional Habits among Young Adults Using Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems in a Multinational Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, M.M.; Alanazi, A.M.M.; Almutairi, A.S.; Pavela, G. Electronic Cigarette Use Is Negatively Associated with Body Mass Index: An Observational Study of Electronic Medical Records. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2020, 7, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, E.; Aronne, L.J. Is It Time to Define Obesity by Body Composition and Not Solely Body Mass Index? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 110, e1278–e1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazić, A.; Jukić, I.; Kolčić, I. Lifestyle Medicine—New Branch of Medicine. Medix 2023, 29, 156–157. [Google Scholar]

- Jiyeon, S.; Oragun, R.; Dennis, S.; Elen, G.; Fariha, H.; Sherzai, D.; Roy, A. Lifestyle and Behavioral Enhancements of Sleep: A Review. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2026, 15598276251410479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N.; Kukkonen-Harjula, K.T.; Verbeek, J.H.; Ijaz, S.; Hermans, V.; Pedisic, Z. Workplace Interventions for Reducing Sitting at Work. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 6, CD010912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kirat, H.; van Belle, S.; Khattabi, A.; Belrhiti, Z. Behavioral Change Interventions, Theories, and Techniques to Reduce Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behavior in the General Population: A Scoping Review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motevalli, M.; Stanford, F.C.; Apflauer, G.; Wirnitzer, K.C. Integrating Lifestyle Behaviors in School Education: A Proactive Approach to Preventive Medicine. Prev. Med. Rep. 2025, 51, 102999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Figueroa, R.; Brink, H.V.; Vorland, C.J.; Auckburally, S.; Johnson, L.; Garay, J.; Brown, T.; Simon, S.; Ells, L. The Efficacy of Sleep Lifestyle Interventions for the Management of Overweight or Obesity in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloran, E.C. Adult Development and Associated Health Risks. J. Patient-Centered Res. Rev. 2024, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Sample (N = 570) |

Women

(N = 478) |

Men

(N = 92) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude toward a healthy lifestyle (score *), Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | 52.0 (10.0) |

51.0 (9.0)

278.8 |

53.0 (8.5)

320.3 | 0.027 † |

| Meal frequency (number of daily meals), Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | 3.0 (1.0) |

3.0 (1.0)

284.6 |

3.0 (1.0)

290.4 | 0.738 † |

| Sitting time (hours per day), Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | 5.0 (4.0) |

5.0 (4.0)

277.0 |

5.0 (4.0)

274.1 | 0.879 † |

| Sleep duration (hours per day), Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | 7.0 (2.0) |

7.0 (2.0)

275.5 |

7.0 (1.0)

319.4 | 0.014 † |

| Body height (m), Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | 1.71 (0.10) |

1.69 (0.37)

245.4 |

1.84 (0.10)

493.7 | <0.001 † |

| Body weight (kg), Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | 73.1 (17.0) |

67.0 (15.0)

250.1 |

85.0 (14.5)

469.2 | <0.001 † |

| BMI (kg/m2), Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | 24.2 (5.1) |

23.1 (4.5)

268.0 |

25.3 (5.2)

376.3 | <0.001 † |

| BMI category, N (%) | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 10 (1.8) | 10 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 365 (64.0) | 322 (67.4) | 43 (46.7) | <0.001 ‡ |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | 152 (26.7) | 114 (23.8) | 38 (41.3) | |

| Obesity (≥30.0 kg/m2) | 43 (7.5) | 32 (6.7) | 11 (12.0) | |

| Cigarette smoking, N (%) | ||||

| No | 365 (64.0) | 303 (63.4) | 62 (67.4) | |

| Yes | 145 (25.4) | 126 (26.4) | 19 (20.7) | 0.498 ‡ |

| Occasionally | 60 (10.5) | 49 (10.3) | 11 (12.0) | |

| E-cigarette use, N (%) | ||||

| No | 450 (78.9) | 371 (77.6) | 79 (85.9) | |

| Yes | 87 (15.3) | 79 (16.5) | 8 (8.7) | 0.150 ‡ |

| Occasionally | 33 (5.8) | 28 (5.9) | 5 (5.4) | |

| Alcohol consumption, N (%) | ||||

| No | 188 (33.0) | 167 (34.9) | 21 (22.8) | |

| Yes | 47 (8.2) | 35 (7.3) | 12 (13.0) | 0.030 ‡ |

| Occasionally | 335 (58.8) | 276 (57.7) | 59 (64.1) | |

| Self-rated health, N (%) | ||||

| Excellent | 157 (27.5) | 110 (23.0) | 47 (51.1) | |

| Very good | 311 (54.6) | 274 (57.3) | 37 (40.2) | <0.001 ‡ |

| Average | 92 (16.1) | 86 (18.0) | 6 (6.5) | |

| Poor | 10 (1.8) | 8 (1.7) | 2 (2.2) |

| Number of Daily Meals | Sitting Time | Sleep Duration | BMI | Attitude Toward a Healthy Lifestyle | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | p Value | Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | p Value | Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | p Value | Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | p Value | Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | p Value | |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤20 | 3.0 (1.0); 329.6 | 0.002 | 6.0 (3.0); 308.6 | 0.004 | 8.0 (1.0); 329.4 | 0.011 | 22.0 (3.2); 193.5 | <0.001 | 50.0 (8.0); 223.1 | 0.095 |

| 21–30 | 3.0 (1.0); 302.1 | 5.0 (4.0); 231.1 | 7.0 (1.0); 313.2 | 22.4 (4.1); 226.4 | 52.0 (10.5); 278.2 | |||||

| 31–45 | 3.0 (1.0); 297.8 | 6.0 (4.0); 282.8 | 7.0 (2.0); 277.3 | 23.5 (4.5); 287.9 | 52.0 (9.6); 300.4 | |||||

| 46–60 | 3.0 (0.8); 247.1 | 5.0 (4.0); 282.8 | 7.0 (2.0); 261.9 | 24.8 (5.3); 338.5 | 51.0 (9.5); 285.9 | |||||

| 61–75 | 3.0 (1.8); 261.3 | 8.0 (5.0); 343.2 | 7.0 (2.0); 237.7 | 25.3 (6.5); 361.5 | 51.0 (9.5); 279.0 | |||||

| Place of residence | ||||||||||

| Rural | 3.0 (1.0); 268.8 | 0.139 | 5.0 (3.0); 231.6 | <0.001 | 7.0 (2.0); 286.3 | 0.741 | 24.2 (4.5); 303.1 | 0.145 | 50.0 (8.0); 262.4 | 0.056 |

| Urban | 3.0 (1.0); 290.9 | 6.0 (4.0); 291.0 | 7.0 (2.0); 281.3 | 23.4 (4.8); 279.8 | 52.0 (10.0); 293.0 | |||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Divorced, widowed, single | 3.0 (1.0); 288.3 | 0.800 | 5.0 (4.0); 274.6 | 0.869 | 7.0 (2.0); 273.5 | 0.428 | 23.2 (4.6); 271.1 | 0.226 | 50.0 (10.0); 263.4 | 0.064 |

| Married/in a relationship | 3.0 (1.0); 284.6 | 5.0 (4.0); 277.1 | 7.0 (2.0); 285.5 | 23.8 (4.9); 290.3 | 52.0 (9.0); 292.9 | |||||

| Education level | ||||||||||

| Primary and high school | 3.0 (1.0); 269.5 | 0.093 | 5.0 (3.0); 229.7 | <0.001 | 7.0 (2.0); 283.6 | 0.907 | 24.5 (4.8); 278.4 | 0.485 | 50.0 (8.0); 240.7 | <0.001 |

| University | 3.0 (1.0); 292.8 | 6.0 (4.0); 297.2 | 7.0 (2.0); 282.0 | 24.8 (5.3); 288.8 | 52.0 (10.0); 306.0 | |||||

| Employment status | ||||||||||

| Unemployed | 3.0 (1.0); 271.7 | 0.454 | 5.0 (4.0); 249.5 | 0.374 | 7.0 (1.0); 337.2 | <0.001 | 21.6 (3.9); 191.6 | <0.001 | 51.5 (7.5); 296.9 | 0.804 |

| Employed | 3.0 (1.0); 282.6 | 5.0 (4.0); 276.9 | 7.0 (1.0); 271.5 | 23.4 (4.8); 301.8 | 52.0 (10.0); 287.0 | |||||

| Student | 3.0 (1.0); 315.8 | 6.0 (2.0); 299.9 | 8.0 (1.0); 360.4 | 22.0 (3.5); 183.5 | 50.0 (10.3); 265.5 | |||||

| Retired | 3.0 (1.0); 299.1 | 5.0 (6.0); 225.8 | 6.5 (4.0); 226.0 | 26.4 (5.8); 352.8 | 51.5 (12.3); 285.6 | |||||

| Type of work | ||||||||||

| Active | 3.0 (1.0); 291.4 | 0.285 | 5.0 (3.0); 212.9 | <0.001 | 7.0 (2.0); 282.2 | 0.961 | 23.2 (4.6); 273.0 | 0.036 | 51.0 (9.0); 281.1 | 0.459 |

| Sedentary | 3.0 (1.0); 277.6 | 8.0 (4.0); 359.8 | 7.0 (2.0); 282.9 | 24.0 (4.9); 302.2 | 52.0 (9.6); 291.4 | |||||

| Caring for a child with a disability | ||||||||||

| No | 3.0 (1.0); 286.4 | 0.505 | 5.0 (4.0); 276.4 | 0.947 | 7.0 (2.0); 284.2 | 0.208 | 23.7 (4.8); 287.8 | 0.103 | 52.0 (10.0); 286.2 | 0.626 |

| Yes | 3.0 (1.0); 264.6 | 5.0 (4.0); 278.7 | 7.0 (2.0); 241.5 | 22.6 (5.7); 230.7 | 52.0 (9.0); 269.1 | |||||

| Caring for a child with a chronic disease | ||||||||||

| No | 3.0 (1.0); 287.5 | 0.118 | 5.0 (4.0); 276.2 | 0.820 | 7.0 (2.0); 285.5 | 0.022 | 23.6 (4.9); 288.4 | 0.036 | 52.0 (10.0); 287.1 | 0.260 |

| Yes | 3.0 (0.8); 235.4 | 5.0 (5.0); 284.2 | 7.0 (2.0); 205.8 | 22.9 (6.0); 213.4 | 49.0 (10.5); 246.7 | |||||

| Caring for an ill adult family member | ||||||||||

| No | 3.0 (1.0); 287.2 | 0.416 | 5.0 (4.0); 277.7 | 0.589 | 7.0 (2.0); 289.8 | 0.001 | 23.5 (4.6); 284.3 | 0.593 | 52.0 (9.0); 292.8 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 3.0 (2.0); 269.3 | 5.0 (4.0); 265.3 | 7.0 (1.0); 212.4 | 24.6 (7.1); 296.9 | 48.0 (8.8); 216.3 | |||||

| Caring for an older person | ||||||||||

| No | 3.0 (1.0); 288.9 | 0.159 | 5.0 (4.0); 281.9 | 0.033 | 7.0 (2.0); 289.8 | 0.003 | 23.6 (4.7); 285.6 | 0.926 | 52.0 (9.0); 292.1 | 0.010 |

| Yes | 3.0 (1.0); 261.1 | 5.0 (5.0); 238.5 | 7.0 (2.0); 228.9 | 24.0 (6.0); 287.2 | 50.0 (8.0); 237.8 | |||||

| Number of Daily Meals | Sitting Time | Sleep Duration | BMI | Attitude Toward a Healthy Lifestyle | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | p Value | Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | p Value | Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | p Value | Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | p Value | Mdn (IQR); Mean Rank | p Value | |

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||||||

| No | 3.0 (1.0); 302.3 | 5.0 (4.0); 277.1 | 7.0 (2.0); 289.6 | 23.6 (4.6); 284.1 | 53.0 (10.0); 320.6 | |||||

| Yes | 3.0 (1.0); 237.5 | <0.001 | 5.0 (4.0); 262.5 | 0.196 | 7.0 (2.0); 268.5 | 0.348 | 24.0 (6.1); 298.6 | 0.346 | 49.0 (8.0); 213.5 | <0.001 |

| Occasionally | 3.0 (1.0); 299.2 | 5.0 (4.0); 307.2 | 7.0 (2.0); 273.3 | 22.9 (4.4); 262.4 | 49.0 (7.0); 245.8 | |||||

| E-cigarette use | ||||||||||

| No | 3.0 (1.0); 295.4 | 0.009 | 5.0 (4.0); 272.0 | 0.252 | 7.0 (2.0); 284.4 | 0.491 | 24.0 (4.9); 296.8 | 0.006 | 52.0 (9.0); 296.3 | 0.004 |

| Yes | 3.0 (1.5); 253.7 | 6.0 (4.0); 284.4 | 7.0 (2.0); 266.0 | 22.5 (3.5); 238.9 | 49.0 (9.5); 231.8 | |||||

| Occasionally | 3.0 (1.0); 233.9 | 6.0 (5.0); 318.0 | 7.0 (1.0); 299.8 | 22.7 (3.4); 255.1 | 51.0 (11.0); 279.4 | |||||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||

| No | 3.0 (1.0); 300.3 | 0.054 | 5.0 (5.0); 257.6 | 0.051 | 7.0 (2.0); 275.1 | 0.366 | 24.2 (4.5); 302.0 | 0.156 | 52.0 (9.0); 300.5 | 0.147 |

| Yes | 3.0 (1.0); 240.7 | 6.0 (3.0); 318.0 | 7.0 (1.0); 311.1 | 24.0 (4.5); 298.8 | 51.0 (7.5); 250.6 | |||||

| Occasionally | 3.0 (1.0); 283.5 | 5.0 (4.0); 281.3 | 7.0 (2.0); 282.7 | 23.1 (4.3); 274.4 | 51.0 (10.0); 282.0 | |||||

| BMI category | ||||||||||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 3.0 (1.0); 286.5 | 0.926 | 6.0 (6.0); 349.1 | 0.328 | 8.0 (3.0); 290.3 | 0.597 | 18.3 (4.5); 5.50 | <0.001 | 54.0 (9.5); 259.4 | <0.001 |

| 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 3.0 (1.0); 286.4 | 5.0 (4.0); 271.7 | 7.0 (2.0); 288.9 | 22.2 (2.5); 193.0 | 53.0 (10.0); 307.3 | |||||

| 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 | 3.0 (1.0); 287.6 | 5.0 (4.0); 275.9 | 7.0 (2.0); 271.7 | 27.1 (2.5); 451.5 | 50.0 (9.0); 255.4 | |||||

| ≥30.0 kg/m2 | 3.0 (1.0); 270.2 | 5.0 (5.0); 303.8 | 7.0 (2.0); 265.0 | 31.3 (3.6); 549.0 | 49.0 (6.0); 213.1 | |||||

| Self-rated health | ||||||||||

| Poor | 3.0 (1.5); 202.0 | 0.066 | 5.0 (7.0); 224.6 | 0.609 | 6.0 (4.0); 178.8 | <0.001 | 24.7 (8.3); 299.1 | 0.145 | 47.0 (11.5); 170.0 | <0.001 |

| Average | 3.0 (1.3); 258.9 | 5.0 (4.0); 266.5 | 7.0 (1.0); 225.7 | 23.9 (6.0); 301.0 | 50.0 (8.5); 228.5 | |||||

| Very good | 3.0 (1.0); 288.9 | 6.0 (5.0); 282.5 | 7.0 (2.0); 275.8 | 23.9 (5.3); 293.4 | 51.0 (9.0); 274.2 | |||||

| Excellent | 3.0 (1.0); 299.6 | 5.0 (4.0); 273.1 | 7.0 (1.0); 335.1 | 23.0 (4.2); 259.9 | 54.0 (11.5); 348.8 | |||||

| Attitude Toward a Healthy Lifestyle | Number of Daily Meals | Sitting Time | Sleep Duration | BMI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Age | 0.21 | <0.001 | −0.26 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.057 | −0.07 | 0.217 | 0.27 | <0.001 |

| Female (male as reference) | −0.03 | 0.513 | −0.01 | 0.881 | 0.07 | 0.084 | −0.04 | 0.339 | −0.24 | <0.001 |

| Urban (rural as reference) | 0.01 | 0.755 | 0.07 | 0.107 | 0.10 | 0.008 | −0.04 | 0.395 | −0.06 | 0.156 |

| Married/in a relationship (no as reference) | 0.02 | 0.556 | −0.07 | 0.140 | 0.02 | 0.708 | 0.11 | 0.011 | −0.03 | 0.545 |

| Having children (yes) | −0.03 | 0.512 | 0.09 | 0.114 | −0.07 | 0.163 | −0.17 | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.734 |

| University degree (no university as reference) | 0.11 | 0.013 | 0.07 | 0.143 | 0.08 | 0.068 | 0.03 | 0.556 | −0.01 | 0.786 |

| Employed (unemployed as reference) | −0.03 | 0.495 | 0.00 | 0.984 | −0.17 | <0.001 | −0.10 | 0.045 | 0.14 | 0.003 |

| Sedentary work (yes) | 0.01 | 0.881 | −0.06 | 0.270 | 0.43 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.569 | −0.05 | 0.256 |

| Caring for a child with a disability (yes) | 0.00 | 0.926 | −0.01 | 0.822 | 0.00 | 0.939 | −0.01 | 0.781 | 0.03 | 0.489 |

| Caring for a child with a chronic disease (yes) | −0.04 | 0.345 | −0.04 | 0.443 | 0.01 | 0.776 | −0.06 | 0.155 | −0.13 | 0.001 |

| Caring for an ill adult family member (yes) | −0.07 | 0.099 | 0.04 | 0.422 | 0.00 | 0.987 | −0.09 | 0.073 | 0.00 | 0.933 |

| Caring for an older person (yes) | −0.02 | 0.668 | −0.03 | 0.535 | −0.08 | 0.073 | −0.04 | 0.391 | −0.02 | 0.705 |

| Cigarette smoking (yes) | −0.18 | <0.001 | −0.07 | 0.097 | −0.01 | 0.859 | 0.00 | 0.990 | −0.01 | 0.872 |

| E-cigarette use (yes) | −0.03 | 0.453 | −0.10 | 0.025 | 0.05 | 0.190 | −0.03 | 0.444 | −0.02 | 0.650 |

| Alcohol consumption (yes) | −0.02 | 0.599 | −0.08 | 0.071 | 0.05 | 0.180 | 0.02 | 0.564 | −0.08 | 0.044 |

| Excellent self-rated health (yes) | 0.19 | <0.001 | −0.08 | 0.103 | 0.02 | 0.566 | 0.09 | 0.038 | −0.06 | 0.165 |

| Attitude toward a healthy lifestyle (score) | - | - | 0.16 | 0.001 | −0.11 | 0.010 | 0.17 | <0.001 | −0.24 | <0.001 |

| Number of daily meals | 0.13 | 0.001 | - | - | 0.00 | 0.905 | 0.05 | 0.249 | 0.03 | 0.499 |

| Sitting time (hours per day) | −0.11 | 0.010 | 0.01 | 0.905 | - | - | 0.08 | 0.074 | 0.04 | 0.334 |

| Sleep duration (hours per day) | 0.15 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.249 | 0.07 | 0.074 | - | - | 0.02 | 0.662 |

| BMI | −0.23 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.499 | 0.04 | 0.334 | 0.02 | 0.662 | - | - |

| β | S.E. | Wald | OR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.05 | 0.01 | 22.08 | 1.06 (1.03–1.08) | <0.001 |

| Female (male as reference) | −1.47 | 0.29 | 25.74 | 0.23 (0.13–0.41) | <0.001 |

| Urban (rural as reference) | −0.37 | 0.24 | 2.23 | 0.69 (0.43–1.12) | 0.135 |

| Married/in a relationship (no as reference) | −0.10 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.91 (0.54–1.52) | 0.710 |

| Having children (yes) | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 1.05 (0.61–1.83) | 0.855 |

| University degree (no university as reference) | −0.25 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.78 (0.48–1.28) | 0.323 |

| Employed (unemployed as reference) | 0.87 | 0.35 | 6.11 | 2.39 (1.20–4.75) | 0.013 |

| Sedentary work (yes) | −0.32 | 0.24 | 1.66 | 0.73 (0.45–1.18) | 0.197 |

| Caring for a child with a disability (yes) | −0.37 | 0.61 | 0.36 | 0.69 (0.21–2.31) | 0.550 |

| Caring for a child with a chronic disease (yes) | −0.95 | 0.63 | 2.24 | 0.39 (0.11–1.34) | 0.134 |

| Caring for an ill adult family member (yes) | −0.04 | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.96 (0.44–2.10) | 0.918 |

| Caring for an older person (yes) | −0.15 | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.86 (0.43–1.75) | 0.680 |

| Cigarette smoking (yes) | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 1.11 (0.71–1.73) | 0.647 |

| E-cigarette use (yes) | −0.64 | 0.29 | 4.82 | 0.53 (0.30–0.93) | 0.028 |

| Alcohol consumption (yes) | −0.37 | 0.23 | 2.66 | 0.69 (0.44–1.08) | 0.103 |

| Attitude toward a healthy lifestyle (score) | −0.08 | 0.02 | 22.96 | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | <0.001 |

| Number of daily meals | 0.15 | 0.10 | 2.20 | 1.17 (0.95–1.43) | 0.138 |

| Sitting time (hours per day) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.27 | 1.05 (0.97–1.13) | 0.261 |

| Sleep duration (hours per day) | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.96 (0.80–1.14) | 0.626 |

| Excellent self-rated health (yes) | −0.19 | 0.27 | 0.51 | 0.83 (0.49–1.39) | 0.477 |

| β | S.E. | Wald | OR (95%CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.06 | 0.01 | 16.84 | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | <0.001 |

| Female (male as reference) | −1.40 | 0.30 | 22.01 | 0.25 (0.14–0.44) | <0.001 |

| Urban (rural as reference) | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 1.17 (0.69–1.97) | 0.562 |

| Married/in a relationship (no as reference) | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 1.12 (0.65–1.94) | 0.677 |

| Having children (yes) | −0.11 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.89 (0.51–1.58) | 0.695 |

| University degree (no university as reference) | −0.04 | 0.29 | 0.02 | 0.96 (0.55–1.68) | 0.893 |

| Employed (unemployed as reference) | 0.65 | 0.37 | 3.08 | 1.92 (0.93–3.97) | 0.079 |

| Sedentary work (yes) | −0.02 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.98 (0.57–1.68) | 0.929 |

| Caring for a child with a disability (yes) | −0.15 | 0.75 | 0.04 | 0.86 (0.20–3.75) | 0.843 |

| Caring for a child with a chronic disease (yes) | −0.73 | 0.87 | 0.70 | 0.48 (0.09–2.64) | 0.402 |

| Caring for an ill adult family member (yes) | −0.72 | 0.62 | 1.35 | 0.49 (0.14–1.64) | 0.245 |

| Caring for an older person (yes) | −0.66 | 0.46 | 2.07 | 0.52 (0.21–1.27) | 0.151 |

| Cigarette smoking (yes) | −0.22 | 0.25 | 0.76 | 0.80 (0.49–1.32) | 0.384 |

| E-cigarette use (yes) | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 1.05 (0.61–1.83) | 0.855 |

| Alcohol consumption (yes) | −0.31 | 0.25 | 1.58 | 0.73 (0.45–1.19) | 0.208 |

| Attitude toward a healthy lifestyle (score) | −0.06 | 0.04 | 2.61 | 0.94 (0.88–1.01) | 0.106 |

| Number of daily meals | −0.23 | 0.12 | 3.68 | 0.80 (0.63–1.00) | 0.055 |

| Sitting time (hours per day) | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.61 | 1.04 (0.95–1.13) | 0.436 |

| Sleep duration (hours per day) | 0.27 | 0.11 | 5.99 | 1.31 (1.05–1.62) | 0.014 |

| BMI | 0.08 | 0.02 | 19.44 | 1.08 (1.04–1.12) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ljubičić, M.; Sorić, T.; Gusar, I.; Vidaković Samaržija, D.; Ivković, G.; Pejdo, A.; Vučak Lončar, J.; Klarin, M.; Šarić, N.; Kolčić, I. Association Between Attitude Toward a Healthy Lifestyle, Lifestyle Behaviors, Sociodemographic Characteristics, and Body Mass Index: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2026, 18, 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030500

Ljubičić M, Sorić T, Gusar I, Vidaković Samaržija D, Ivković G, Pejdo A, Vučak Lončar J, Klarin M, Šarić N, Kolčić I. Association Between Attitude Toward a Healthy Lifestyle, Lifestyle Behaviors, Sociodemographic Characteristics, and Body Mass Index: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2026; 18(3):500. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030500

Chicago/Turabian StyleLjubičić, Marija, Tamara Sorić, Ivana Gusar, Donata Vidaković Samaržija, Gordana Ivković, Ana Pejdo, Jelena Vučak Lončar, Mira Klarin, Nita Šarić, and Ivana Kolčić. 2026. "Association Between Attitude Toward a Healthy Lifestyle, Lifestyle Behaviors, Sociodemographic Characteristics, and Body Mass Index: A Cross-Sectional Study" Nutrients 18, no. 3: 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030500

APA StyleLjubičić, M., Sorić, T., Gusar, I., Vidaković Samaržija, D., Ivković, G., Pejdo, A., Vučak Lončar, J., Klarin, M., Šarić, N., & Kolčić, I. (2026). Association Between Attitude Toward a Healthy Lifestyle, Lifestyle Behaviors, Sociodemographic Characteristics, and Body Mass Index: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 18(3), 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030500