Nuciferine Ameliorates Lipotoxicity-Mediated Myocardial Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury by Reducing Reverse Electron Transfer Mediated Oxidative Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

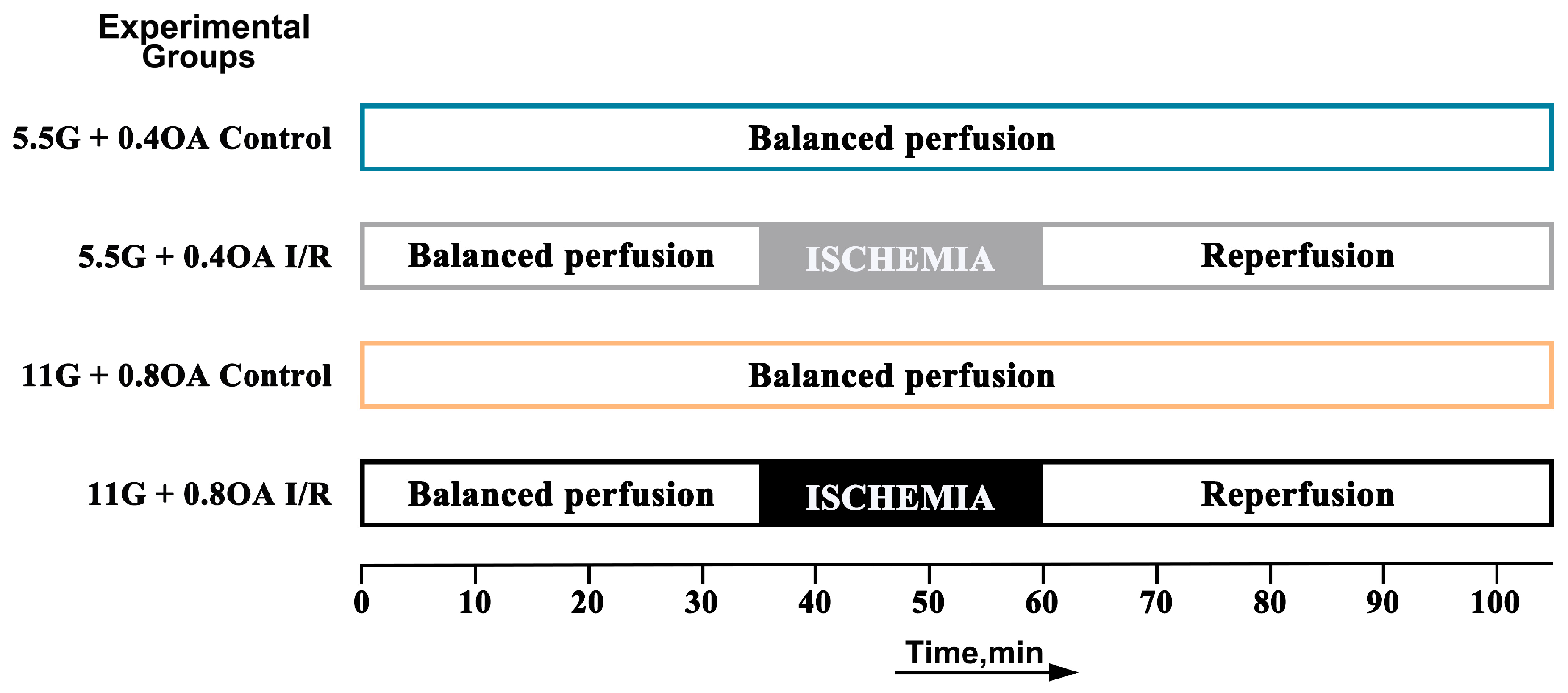

2.2. Study Design and Experimental Protocols

2.3. Myocardial I/R Injury Model with Mouse Isolated Heart

2.4. 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride (TTC) Staining

2.5. Quantification of Myocardial Succinate Accumulation by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

2.6. Isolation of Myocardial Mitochondria

2.7. Measurement of Myocardial Mitochondrial H2O2 Release

2.8. Complex I Activity, SDH Activity and NAD+/NADH Ratio Assay

2.9. Western Blotting Assay

2.10. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study

2.11. Cell Line and Cell Culture

2.12. Lipotoxicity Combined with Hypoxia–Reoxygenation Model

2.13. Cell Morphology Observation

2.14. Sulforhodamine B Assay

2.15. Lactate Dehydrogenase Release Assay

2.16. Evaluation of AC16 Cell Apoptosis by AO/EB Staining and Flow Cytometry (FCM)

2.17. Change in Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (JC-1 Staining)

2.18. Measurement of Intracellular and Mitochondrial ROS

2.19. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. High Glucose Combined with High Oleic Acid Perfusion Aggravates Myocardial Ischemic/Reperfusion Injury in Isolated Mouse Heart

3.2. Nuciferine Attenuates High Glucose/Oleic Acid-Exacerbated Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury

3.3. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Assessment

3.4. Nuciferine Regulates Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Maintains Fusion-Fission Homeostasis

3.5. Oleic Acid Exacerbates H/R-Induced Cardiac Myocytes Injury

3.6. Nuciferine Alleviates AC16 Cardiomyocytes Damage Induced by Oleic Acid Combined with H/R

3.7. Dimethyl Malonate Reverses AC16 Cardiomyocytes Damage Induced by Oleic Acid and H/R

3.8. Inhibition of Sirt1 Attenuates the Protective Effect of Nuciferine on Cardiomyocyte Injury Induced by Oleic Acid Combined with H/R

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC16 | human cardiomyocyte cells |

| AO | acridine orange |

| AMPK | 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase |

| CoQ | coenzyme Q |

| CVDs | cardiovascular diseases |

| DMM | dimethyl malonate |

| Drp1 | dynamin-related protein 1 |

| EB | ethidium bromide |

| ECL | enhanced chemiluminescence |

| EX527 | selisistat |

| FACS | fluorescence-activated cell sorting |

| FAD | flavin adenine dinucleotide |

| FCM | Flow Cytometry |

| FET | forward electron transport |

| FFAs | free fatty acids |

| FMN | flavin mononucleotide |

| GAPDH | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| HFD | high-fat diet |

| H/R | hypoxia/reoxygenation |

| HRP | horseradish peroxidase |

| I/R | ischemia–reperfusion |

| KH | Krebs–Henseleit buffer |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| LVEDP | left ventricular end-diastolic pressure |

| LVDP | left ventricular developed pressure |

| MD | molecular dynamics |

| Mfn2 | mitochondrial fusion proteins 2 |

| MI/R | myocardial ischemia/reperfusion |

| MMP | mitochondrial membrane potential |

| PDA | photodiode array |

| PGC-1α | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha |

| PI | propidium iodide |

| PVDF | polyvinylidene fluoride |

| RET | reverse electron transport |

| Rg | radius of gyration |

| RMSD | root mean square deviation |

| RMSF | root mean square fluctuation |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RPP | rate-LV pressure product |

| SDS-PAGE | sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| Sirt1 | sirtuin 1 |

| SRB | sulforhodamine B |

| STZ | streptozotocin |

| TCA | tricarboxylic acid |

| TFAM | mitochondrial transcription factor A |

| TTC | 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

References

- Algoet, M.; Janssens, S.; Himmelreich, U.; Gsell, W.; Pusovnik, M.; van den Eynde, J.; Oosterlinck, W. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and the influence of inflammation. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 33, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Z.; Kolwicz, S.C., Jr.; Abell, L.; Roe, N.D.; Kim, M.; Zhou, B.; Cao, Y.; Ritterhoff, J.; Gu, H.; et al. Defective Branched-Chain Amino Acid Catabolism Disrupts Glucose Metabolism and Sensitizes the Heart to Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turer, A.T.; Stevens, R.D.; Bain, J.R.; Muehlbauer, M.J.; van der Westhuizen, J.; Mathew, J.P.; Schwinn, D.A.; Glower, D.D.; Newgard, C.B.; Podgoreanu, M.V. Metabolomic profiling reveals distinct patterns of myocardial substrate use in humans with coronary artery disease or left ventricular dysfunction during surgical ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation 2009, 119, 1736–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Duan, C.; Wang, P.; Zhang, S.; Gao, Y.; Lu, S.; Ji, Y. 4-Octyl Itaconate Alleviates Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Through Promoting Angiogenesis via ERK Signaling Activation. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2411554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, M.; Li, B.; Duan, W.; Jing, L.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, M.; Yu, L.; Liu, Z.; Yu, B.; Ren, K.; et al. Melatonin ameliorates myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury through SIRT3-dependent regulation of oxidative stress and apoptosis. J. Pineal Res. 2017, 63, e12419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cui, J.; Zhao, F.; Yang, L.; Xu, X.; Shi, Y.; Wei, B. Cardioprotective effect of MLN4924 on ameliorating autophagic flux impairment in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by Sirt1. Redox Biol. 2021, 46, 102114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prag, H.A.; Murphy, M.P.; Krieg, T. Preventing mitochondrial reverse electron transport as a strategy for cardioprotection. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2023, 118, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryde, K.R.; Hirst, J. Superoxide is produced by the reduced flavin in mitochondrial complex I: A single, unified mechanism that applies during both forward and reverse electron transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 18056–18065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.J.; Biner, O.; Chung, I.; Burger, N.; Bridges, H.R.; Hirst, J. Reverse Electron Transfer by Respiratory Complex I Catalyzed in a Modular Proteoliposome System. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 6791–6801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E.T.; Pell, V.R.; Gaude, E.; Aksentijević, D.; Sundier, S.Y.; Robb, E.L.; Logan, A.; Nadtochiy, S.M.; Ord, E.N.J.; Smith, A.C.; et al. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature 2014, 515, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.T.; Miller, J.H.; Day, M.M.; Munger, J.C.; Brookes, P.S. Accumulation of Succinate in Cardiac Ischemia Primarily Occurs via Canonical Krebs Cycle Activity. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 2617–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.L.; Costa, A.S.H.; Gruszczyk, A.V.; Beach, T.E.; Allen, F.M.; Prag, H.A.; Hinchy, E.C.; Mahbubani, K.; Hamed, M.; Tronci, L.; et al. Succinate accumulation drives ischaemia-reperfusion injury during organ transplantation. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, M.; Yin, H.; Jiang, K.; Wu, H.; Dai, A.; Yang, S. Nuciferine alleviates LPS-induced mastitis in mice via suppressing the TLR4-NF-κB signaling pathway. Inflamm. Res. 2018, 67, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.R.; Gautam, L.N.; Adhikari, D.; Karki, R. A Comprehensive Review on Chemical Profiling of Nelumbo Nucifera: Potential for Drug Development. Phytother. Res. PTR 2017, 31, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harishkumar, R.; Christopher, J.G.; Ravindran, R.; Selvaraj, C.I. Nuciferine Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity: An In Vitro and In Vivo Study. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2021, 21, 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Li, G.; He, Y.; Xu, B.; Mi, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z. Pronuciferine and nuciferine inhibit lipogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by activating the AMPK signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2015, 136, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Shi, A.; Tang, X.; Xia, P.; Zhang, J.; Yu, P. AMPK: The key to ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Cell. Physiol. 2022, 237, 4079–4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukarainen, S.; Heinonen, S.; Rämö, J.T.; Rinnankoski-Tuikka, R.; Rappou, E.; Tummers, M.; Muniandy, M.; Hakkarainen, A.; Lundbom, J.; Lundbom, N.; et al. Obesity Is Associated with Low NAD(+)/SIRT Pathway Expression in Adipose Tissue of BMI-Discordant Monozygotic Twins. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, S.; Tantray, I.; Li, Y.; Khaket, T.P.; Li, Y.; Bhurtel, S.; Li, W.; Zeng, C.; Lu, B. Reverse electron transfer is activated during aging and contributes to aging and age-related disease. EMBO Rep. 2023, 24, e55548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavda, V.; Lu, B. Reverse Electron Transport at Mitochondrial Complex I in Ischemic Stroke, Aging, and Age-Related Diseases. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-Y.; He, K.; Pan, C.-S.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Yan, L.; Wei, X.-H.; Hu, B.-H.; Chang, X.; Mao, X.-W.; et al. 3, 4-dihydroxyl-phenyl lactic acid restores NADH dehydrogenase 1 α subunit 10 to ameliorate cardiac reperfusion injury. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.P.; Zhai, P.; Yamamoto, T.; Maejima, Y.; Matsushima, S.; Hariharan, N.; Shao, D.; Takagi, H.; Oka, S.; Sadoshima, J. Silent information regulator 1 protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation 2010, 122, 2170–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Li, Q.; Yu, B.; Yang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Duan, W.; Zhao, G.; Zhai, M.; Liu, L.; Yi, D.; et al. Berberine Attenuates Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Reducing Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Response: Role of Silent Information Regulator 1. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 1689602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Cao, W.; Yue, R.; Yuan, Y.; Guo, X.; Qin, D.; Xing, J.; Wang, X. Pretreatment with Tilianin improves mitochondrial energy metabolism and oxidative stress in rats with myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1 alpha signaling pathway. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 139, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, E.A.; Kasinski, A.L. Sulforhodamine B (SRB) Assay in Cell Culture to Investigate Cell Proliferation. Bio-Protocol 2016, 6, e1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobner, D. Comparison of the LDH and MTT assays for quantifying cell death: Validity for neuronal apoptosis? J. Neurosci. Methods 2000, 96, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, Y.; Cui, Y.; Li, S.; Zhu, Y.; Shang, C.; Song, G.; Liu, Z.; Xiu, Z.; Cong, J.; et al. Anti-tumour effects of a dual cancer-specific oncolytic adenovirus on Breast Cancer Stem cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.J.; Calamaras, T.; Elezaby, A.; Sverdlov, A.; Qin, F.; Luptak, I.; Wang, K.; Sun, X.; Vijay, A.; Croteau, D.; et al. Partial Liver Kinase B1 (LKB1) Deficiency Promotes Diastolic Dysfunction, De Novo Systolic Dysfunction, Apoptosis, and Mitochondrial Dysfunction with Dietary Metabolic Challenge. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 5, e002277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Q.; Liu, J.; Tong, X.L.; Peng, W.J.; Wei, S.S.; Sun, T.L.; Wang, Y.K.; Zhang, B.K.; Li, W.Q. Network Pharmacology Prediction and Molecular Docking-Based Strategy to Discover the Potential Pharmacological Mechanism of Huai Hua San Against Ulcerative Colitis. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 3255–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekeschus, S.; Poschkamp, B.; van der Linde, J. Medical gas plasma promotes blood coagulation via platelet activation. Biomaterials 2021, 278, 120433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Song, Y.; Fu, K.; Gao, Z.; Liu, D.; He, W.; Yang, L.L. Energy metabolism in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, R.; Xiong, S.; Sun, J.; Zhang, J.; Fan, D.; Deng, J.; Yang, H. Structure-activity relationship, bioactivities, molecular mechanisms, and clinical application of nuciferine on inflammation-related diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 193, 106820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambrova, M.; Zuurbier, C.J.; Borutaite, V.; Liepinsh, E.; Makrecka-Kuka, M. Energy substrate metabolism and mitochondrial oxidative stress in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 165, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009, 417, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pell, V.R.; Chouchani, E.T.; Frezza, C.; Murphy, M.P.; Krieg, T. Succinate metabolism: A new therapeutic target for myocardial reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2016, 111, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pell, V.R.; Chouchani, E.T.; Murphy, M.P.; Brookes, P.S.; Krieg, T. Moving Forwards by Blocking Back-Flow: The Yin and Yang of MI Therapy. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 898–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlström, M.; Rannier Ribeiro Antonino Carvalho, L.; Guimaraes, D.; Boeder, A.; Schiffer, T.A. Dimethyl malonate preserves renal and mitochondrial functions following ischemia-reperfusion via inhibition of succinate dehydrogenase. Redox Biol. 2024, 69, 102984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghavi, S.; Abdullah, S.; Toraih, E.; Packer, J.; Drury, R.H.; Aras, O.A.Z.; Kosowski, E.M.; Cotton-Betteridge, A.; Karim, M.; Bitonti, N.; et al. Dimethyl malonate slows succinate accumulation and preserves cardiac function in a swine model of hemorrhagic shock. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022, 93, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.J.; Wang, H.; Du, Y.; Guan, J.; Wang, X.; Fu, J. NAD(+) improves cognitive function and reduces neuroinflammation by ameliorating mitochondrial damage and decreasing ROS production in chronic cerebral hypoperfusion models through Sirt1/PGC-1α pathway. J. Neuroinflamm. 2021, 18, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, Y.L.; Li, L.Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Q.; Liu, K.; Li, P.; Liu, B.; Qi, L.W. Succinate accumulation impairs cardiac pyruvate dehydrogenase activity through GRP91-dependent and independent signaling pathways: Therapeutic effects of ginsenoside Rb1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 2835–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prag, H.A.; Pala, L.; Kula-Alwar, D.; Mulvey, J.F.; Luping, D.; Beach, T.E.; Booty, L.M.; Hall, A.R.; Logan, A.; Sauchanka, V.; et al. Ester Prodrugs of Malonate with Enhanced Intracellular Delivery Protect Against Cardiac Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury In Vivo. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2022, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Qin, X.; Yue, L.; Liu, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, F.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Q. Nuciferine improves cardiac function in mice subjected to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by upregulating PPAR-γ. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HarishKumar, R.; Selvaraj, C.I. Nuciferine from Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. attenuates isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in Wistar rats. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2022, 69, 1176–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Subunit | Binding Affinity (kcal/mol) | Subunit | Binding Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| complex I | −8.0 | SDH | −8.3 |

| −7.3 | −8.3 | ||

| −7.1 | −8.3 | ||

| −7.0 | −8.3 | ||

| −7.0 | −8.3 | ||

| −7.0 | −8.2 | ||

| −6.8 | −8.2 | ||

| −6.8 | −8.2 | ||

| −6.3 | −8.2 | ||

| Mean ± SD | −7.14 ± 0.47 | Mean ± SD | −8.26 ± 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Shi, X.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, J.; Diao, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, Z.; Ma, C. Nuciferine Ameliorates Lipotoxicity-Mediated Myocardial Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury by Reducing Reverse Electron Transfer Mediated Oxidative Stress. Nutrients 2026, 18, 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030425

Wang M, Shi X, Zhou Y, Feng J, Diao Y, Li G, Wang Z, Ma C. Nuciferine Ameliorates Lipotoxicity-Mediated Myocardial Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury by Reducing Reverse Electron Transfer Mediated Oxidative Stress. Nutrients. 2026; 18(3):425. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030425

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Man, Xiaobing Shi, Yufeng Zhou, Jianhui Feng, Yining Diao, Gang Li, Zhenhua Wang, and Chengjun Ma. 2026. "Nuciferine Ameliorates Lipotoxicity-Mediated Myocardial Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury by Reducing Reverse Electron Transfer Mediated Oxidative Stress" Nutrients 18, no. 3: 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030425

APA StyleWang, M., Shi, X., Zhou, Y., Feng, J., Diao, Y., Li, G., Wang, Z., & Ma, C. (2026). Nuciferine Ameliorates Lipotoxicity-Mediated Myocardial Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury by Reducing Reverse Electron Transfer Mediated Oxidative Stress. Nutrients, 18(3), 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030425