Dietary Use of Hericium coralloides for NAFLD Prevention

Abstract

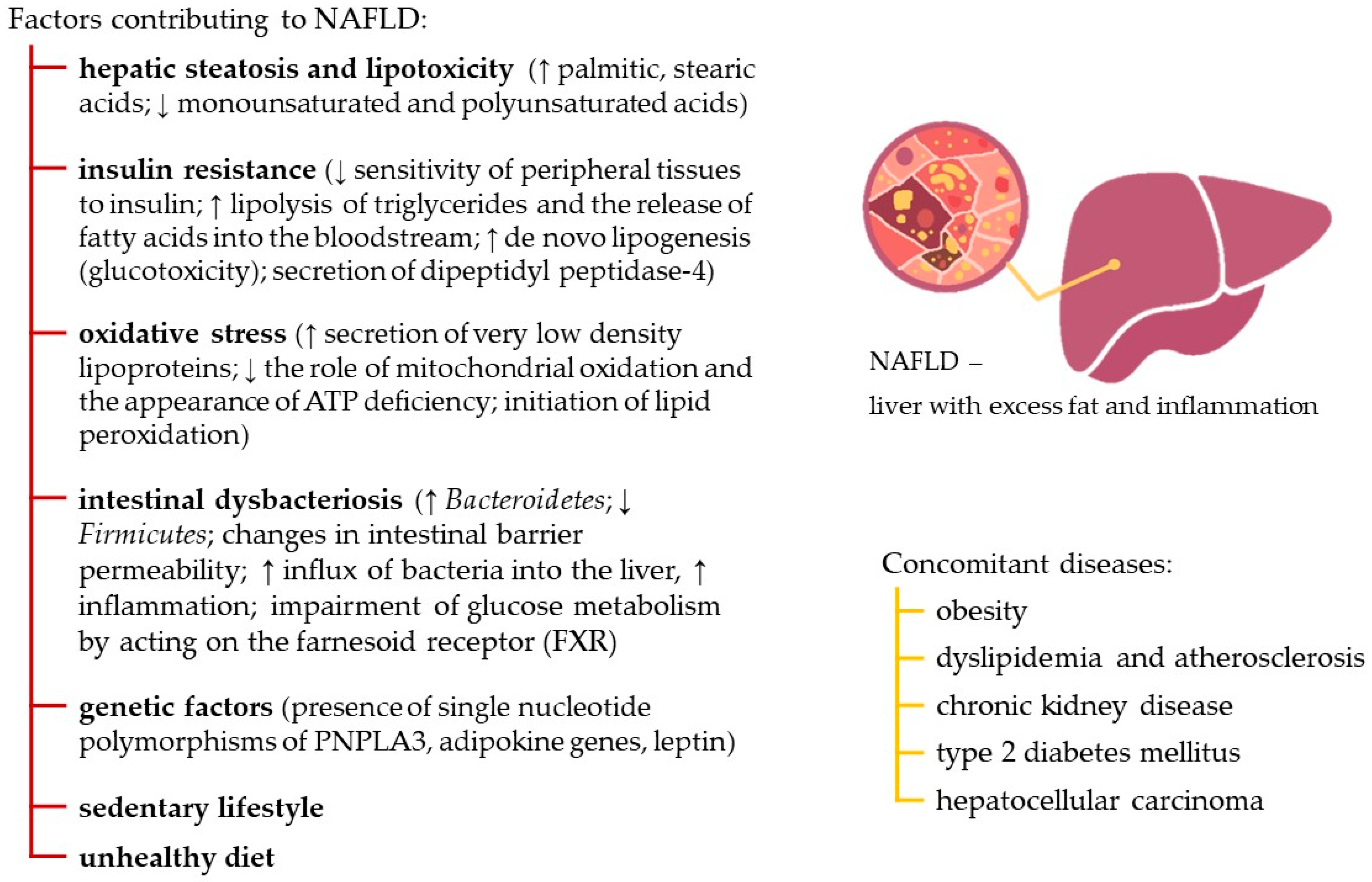

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Review general information about Hericium coralloides;

- (2)

- Examine the metabolic composition of the fungus, methods for its extraction, and extract yield;

- (3)

- Analyze the market of dietary supplements containing Hericium coralloides (or its metabolites).

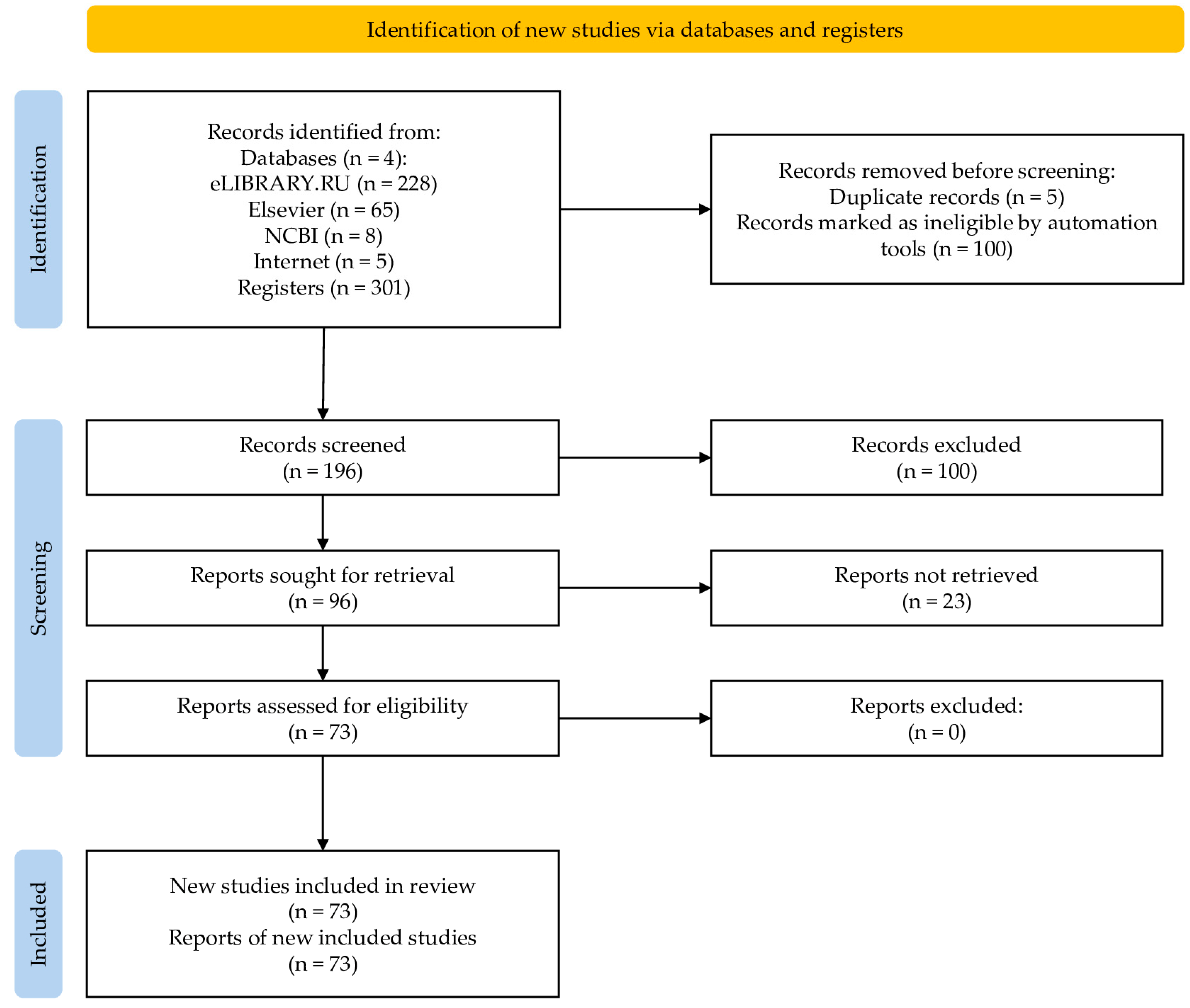

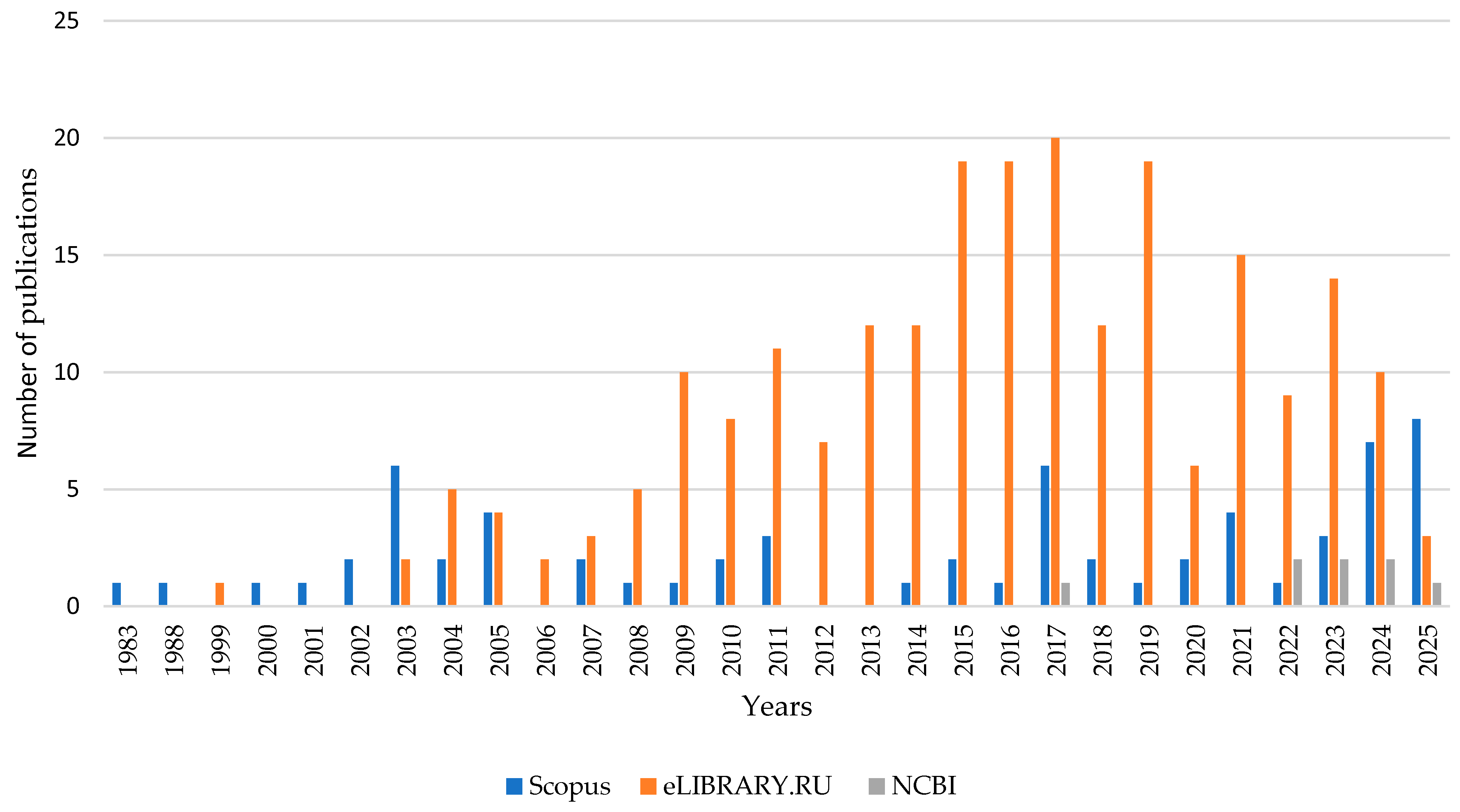

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

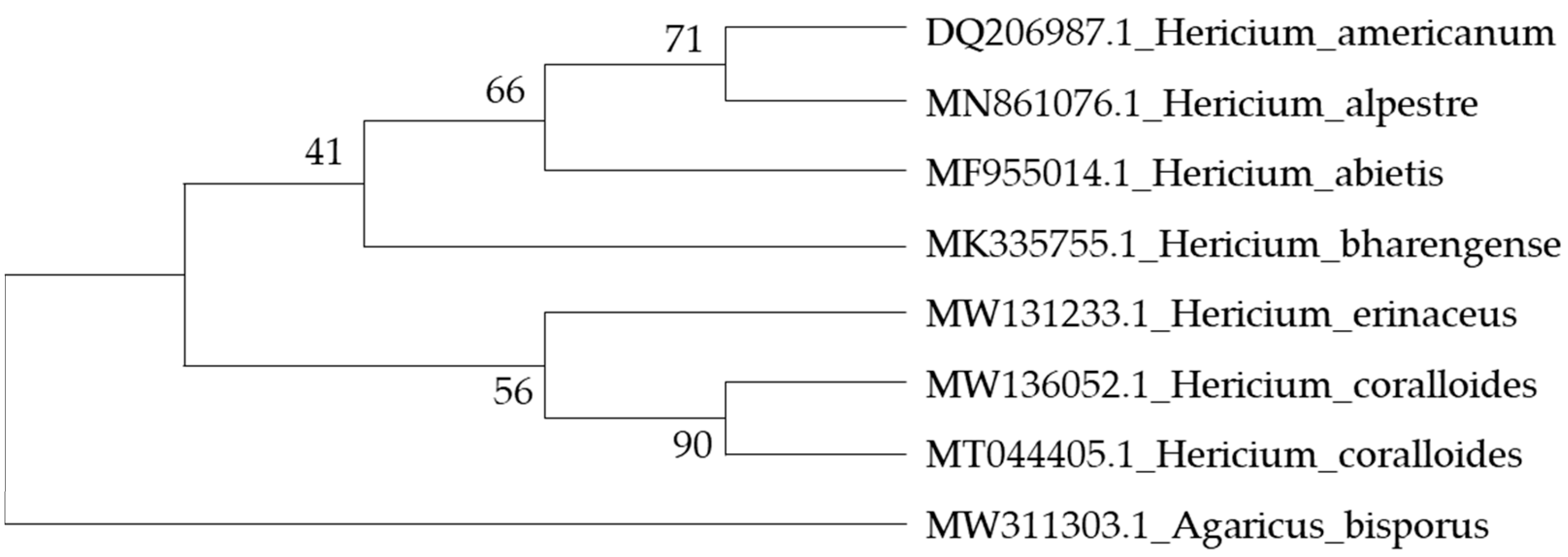

3.1. Information on Hericium coralloides

3.2. H. coralloides Metabolites, Methods of Their Extraction, and Extract Yield

- High-reflux extraction (HRE-P);

- Acid-base extraction;

- Enzymatic extraction;

- Ultrasonic-assisted extraction (UAE-P);

- Cold water extraction (CWE-P);

- Pressurized hot water extraction (PHE-P).

3.3. The Market of Dietary Supplements Containing Hericium coralloides (or Its Metabolites)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheremukhina, Y.V.; Borovkova, N.Y.; Vasilkova, A.S.; Vlasova, T.V.; Akhmedzhanov, N.M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A view formation on the problem and its significance for the clinical practice. Russ. J. Prev. Med. 2025, 28, 127–132. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kytikova, O.Y.; Novgorodtseva, T.P.; Denisenko, Y.K.; Kovalevsky, D.A. Metabolic and Genetic Determinants of Lipid Metabolism Disruption in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Russ. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Coloproctol. 2020, 30, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meroni, M.; Longo, M.; Rustichelli, A.; Dongiovanni, P. Nutrition and Genetics in NAFLD: The Perfect Binomium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshetova, M.S.; Zol’nikova, O.Y.; Ivashkin, V.T.; Ivashkin, K.V.; Appolonova, S.A.; Lapina, T.L. Rol’ kishechnoj mik-robioty i ee metabolitov v patogeneze nealkogol’noj zhirovoj bolezni pecheni. Ross. Zhurnal Gastroentero-Logii Gepatologii Koloproktol. 2022, 32, 75–88. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekushkina, D.Y.; Fedorova, A.M.; Kovalenko, S.V.; Milentyeva, I.S.; Altshuler, O.G.; Aksenova, L.M. Anti-Metabolic Syndrome Effect of Trans-Cinnamic Acid. Food Process. Tech. Technol. 2025, 55, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosobyan, E.P.; Smirnova, O.M. Modern concepts of pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes Mellit. 2010, 13, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Vesnina, A.; Le, V.; Ivanova, S.; Prosekov, A. Antidiabetic Potential of Mangiferin: An In Silico and In Vivo Approach. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalasani, N.; Younossi, Z.; Lavine, J.E.; Charlton, M.; Cusi, K.; Rinella, M.; Harrison, S.A.; Brunt, E.M.; Sanyal, A.J. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018, 67, 328–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesnina, A.D.; Frolova, A.S.; Chekushkina, D.Y.u.; Milentyeva, I.S.; Luzyanin, S.L.; Aksenova, L.M. Gut microbiota and its role in development of chronic disease and aging. Foods Raw Mater. 2026, 14, 174–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosekov, A.Y.; Vesnina, A.D.; Lyubimova, N.A.; Chekushkina, D.Y.; Mikhailova, E.S. Consumer Genomics in Personalized Nutrition. Food Process. Tech. Technol. 2025, 55, 400–415. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wei, Z.; Luo, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, G.; Guan, X.; She, Z.; Liu, W.; Tong, Y.; Liu, H.; et al. Integrated bioinformatics and multiomics reveal Liupao tea extract alleviating NAFLD via regulating hepatic lipid metabolism and gut microbiota. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2024, 132, 155834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poluektova, E.A.; Beniashvili, A.G.; Maslennikov, R.V. Nutraceuticals and Pharmaceuticals. Russ. J. Gastro-Enterol. Hepatol. Coloproctol. 2020, 30, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangour, A.D.; Lock, K.; Hayter, A.; Aikenhead, A.; Allen, E.; Uauy, R. Nutrition-related health effects of organic foods: A systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, A.S.; Vesnina, A.D.; Fedorova, A.M.; Milentyeva, I.S.; Prosekov, A.Y.u.; Zaushintsena, A.V. Hypoglycemic and hypocholesterolemic activities in vivo of polyphenols-popular components of dietary supplements. Nutr. Issues 2025, 94, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, P.; Cui, Y.; Hu, X.; Chen, F.; Ma, C. Alleviation Effects of Microbial Metabolites from Resveratrol on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Foods 2022, 12, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobrysheva, T.N.; Anisimov, G.S.; Zolotoreva, M.S.; Evdokimov, I.A.; Budkevich, R.O.; Muravyev, A.K. Encapsulated polyphenols in functional food production. Foods Raw Mater. 2025, 13, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchendu, I.K.; Ikebunwa, O.A.; Okpagu, C.B. Cardiorenal protective effects of extracts of bitter leaf (Vernonia amygdalina L.) in animal model of metabolic syndrome. Foods Raw Mater. 2024, 12, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yu, K.; Li, F.; Xu, K.; Li, J.; He, S.; Cao, S.; Tan, G. Anticancer potential of Hericium erinaceus extracts against human gastrointestinal cancers. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Hu, Z.; Lv, Y.; Ge, C.; Luo, X.; Zhan, S.; Huang, W.; Shen, X.; Yu, D.; Liu, B. Hericium erinaceus polysaccharides ameliorate nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via gut microbiota and tryptophan metabolism regulation in an aged laying hen model. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 132735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wang, X.; Fang, J.; Chang, Y.; Ning, N.; Guo, H.; Huang, L.; Huang, X.; Zhao, Z. Structures, biological activities, and industrial applications of the polysaccharides from Hericium erinaceus (Lion’s Mane) mushroom: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 97, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, N.S.; Harsh, N.S.K. Relationship of lag phase duration to the texture and occurrence of wood-decaying fungi. Bull. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1983, 17, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostanda, E.; Musa, S.; Pereman, I. Unveiling the Chemical Composition and Biofunctionality of Hericium spp. Fungi: A Comprehensive Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabibzadeh, F.; Alvandi, H.; Hatamian-Zarmi, A.; Kalitukha, L.; Aghajani, H.; Ebrahimi-Hosseinzadeh, B. Antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity of exopolysaccharide from mushroom Hericium coralloides in submerged fermentation. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 26953–26963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallua, J.D.; Recheis, W.; Pöder, R.; Pfaller, K.; Pezzei, C.; Hahn, H.; Huck-Pezzei, V.; Bittner, L.K.; Schaefer, G.; Steiner, E.; et al. Morphological and tissue characterization of the medicinal fungus Hericium coralloides by a structural and molecular imaging platform. Analyst 2012, 137, 1584–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, L.D. Dva redkih vida gribov (Hericium coralloides i Polyporus umbellatus) na territorii Glavnogo botaniche-skogo sada Rossijskoj akademii nauk. Byulleten’ Mosk. Obs. Ispyt. Prir. Otd. Biol. 2019, 124, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Triskiba, S.D. A new find of the fungus Hericium coralloides (Fr.) Pers. (Basidiomycota: Agaricomycetes: Hericiaceae) on the Donetsk Upland. Promyshlennaya Bot. 2022, 22, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Bhardwaj, K.; Sharma, R.; Nepovimova, E.; Cruz-Martins, N.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Singh, R.; Chopra, C.; Verma, R.; Abd-Elsalam, K.A.; et al. Potential Usage of Edible Mushrooms and Their Residues to Retrieve Valuable Supplies for Industrial Applications. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Shi, D.; Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Song, W.; Liu, S.; Wang, C. Hericium coralloides Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease Pathologies and Cognitive Disorders by Activating Nrf2 Signaling and Regulating Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumla, J.; Thangrongthong, S.; Kaewnunta, A.; Suwannarach, N. Research advances in fungal polysaccharides: Production, extraction, characterization, properties, and their multifaceted applications. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1604184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupcic, Z.; Rascher, M.; Kanaki, S.; Köster, R.W.; Stadler, M.; Wittstein, K. Two New Cyathane Diterpenoids from Mycelial Cultures of the Medicinal Mushroom Hericium erinaceus and the Rare Species, Hericium flagellum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cai, J.; Li, X.; Hu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Fu, J. Domestication Cultivation and Nutritional Analysis of Hericium coralloides. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, K.; Lv, J.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, B.; Huang, Q.; Xie, B.; Fu, J. Chromosome-Scale Genome and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal Differential Regulation of Terpenoid Secondary Metabolites in Hericium coralloides. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.-F.; Lv, G.-Y.; Song, T.-T.; Xu, Z.-W.; Wang, M.-Y. Effects of different extraction methods on the structural and biological properties of Hericium coralloides polysaccharides. Food Chem. 2024, 445, 138752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, D.D.; Yin, J.Y.; Nie, S.P.; Xie, M.Y. Recent developments in Hericium erinaceus polysaccharides: Extraction, purification, structural characteristics and biological activities. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, S96–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittstein, K.; Rascher, M.; Rupcic, Z.; Löwen, E.; Winter, B.; Köster, R.W.; Stadler, M. Corallocins A-C, Nerve Growth and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Inducing Metabolites from the Mushroom Hericium coralloides. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 2264–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.H.; Hong, S.M.; Khan, Z.; Lee, S.K.; Vishwanath, M.; Turk, A.; Yeon, S.W.; Jo, Y.H.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, J.K.; et al. Neurotrophic isoindolinones from the fruiting bodies of Hericium erinaceus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 31, 127714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum, W.C.; Gonkhom, D.; Ibrahim, M.A.A.; Stadler, M.; Ebada, S.S. New isoindolinone derivatives isolated from the fruiting bodies of the basidiomycete Hericium coralloides. Mycol. Prog. 2023, 23, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Mármol, R.; Chai, Y.; Conroy, J.N.; Khan, Z.; Hong, S.-M.; Kim, S.B.; Gormal, R.S.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, J.K.; Coulson, E.J.; et al. Hericerin derivatives activates a pan-neurotrophic pathway in central hippocampal neurons converging to ERK1/2 signaling enhancing spatial memory. J. Neurochem. 2023, 165, 791. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Bao, L.; Qi, Q.; Zhao, F.; Ma, K.; Pei, Y.; Liu, H. Erinacerins C-L, isoindolin-1-ones with α-glucosidase inhibitory activity from cultures of the medicinal mushroom Hericium erinaceus. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazur, J.; Kała, K.; Krakowska, A.; Sułkowska-Ziaja, K.; Szewczyk, A.; Piotrowska, J.; Rospond, B.; Fidurski, M.; Marzec, K.; Muszyńska, B. Analysis of bioactive substances and essential elements of mycelia and fruiting bodies of Hericium spp. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 127, 105981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, F.; Colognato, R.; Galetta, F.; Laurenza, I.; Barsotti, M.; Di Stefano, R.; Bocchetti, R.; Regoli, F.; Carpi, A.; Balbarini, A.; et al. An In Vitro Study on the Free Radical Scavenging Capacity of Ergothioneine: Comparison with Reduced Glutathione, Uric Acid and Trolox. Biomed. Pharmacother 2006, 60, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhou, W.; Kim, E.J.; Shim, S.H.; Kang, H.K.; Kim, Y.H. Isolation and identification of aromatic compounds in Lion’s Mane Mushroom and their anticancer activities. Food Chem. 2015, 170, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Song, M.; Wang, C.; Guo, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, D. Structural characterization of polysaccharide purified from Hericium erinaceus fermented mycelium and its pharmacological basis for application in Alzheimer’s disease: Oxidative stress related calcium homeostasis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, D.; Ou, S.; Huang, H. Structural characterization of a novel polysaccharide fraction from Hericium erinaceus and its signaling pathways involved in macrophage immunomodulatory activity. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 37, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Feng, J.; Liu, C.; Hou, S.; Meng, J.; Liu, J.Y.; Zilong, S.; Chang, M.C. Polysaccharides from an edible mushroom, Hericium erinaceus, alleviate ulcerative colitis in mice by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasomes and reestablish intestinal homeostasis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 267, 131251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y.; Chen, Y.P.; Lin, T.W.; Li, T.J.; Chen, Y.W.; Li, I.C.; Chen, C.C. Discovery of a New Compound, Erinacerin W, from the Mycelia of Hericium erinaceus, with Immunomodulatory and Neuroprotective Effects. Molecules 2024, 29, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum, W.C.; Ebada, S.S.; Kirchenwitz, M.; Kellner, H.; Ibrahim, M.A.A.; Stradal, T.E.B.; Matasyoh, J.C.; Stadler, M. Hericioic Acids A-G and Hericiofuranoic Acid; Neurotrophic Agents from Cultures of the European Mushroom Hericium flagellum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 11094–11103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimbo, M.; Kawagishi, H.; Yokogoshi, H. Erinacine A increases catecholamine and nerve growth factor content in the central nervous system of rats. Nutr. Res. 2005, 25, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Zhu, G.; Shang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Ji, X.; Wei, Y. An overview on the biological activity and anti-cancer mechanism of lovastatin. Cell. Signal. 2021, 87, 110122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.T.; Shen, L. Ergothioneine as a natural antioxidant against oxidative stress-related diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 850813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.N.; Wang, L.; Guo, X.L. Chemical constituents from the culture of the fungus Hericium alpestre. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 21, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.; Wu, J.; Kang, S.; Gao, J.; Hirokazu, K.; Liu, H.; Liu, C. The chemical structures, biosynthesis, and biological activities of secondary metabolites from the culinary-medicinal mushrooms of the genus Hericium: A review. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2024, 22, 676–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.Y.; Tao, L.; Lou, D.; Patabendige, N.M.; Ediriweera, A.N.; Liu, S.; Lu, W.; Tarafder, E.; Rapior, S.; Hapuarachchi, K.K. Innovative applications of medicinal mushrooms in functional foods and nutraceuticals: A focus on health-boosting beverages. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1605301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPb ART-LAJF. Available online: https://www.spb-artlife.ru/art-layf---sorbiotik-250-g/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Ozon. Available online: https://www.ozon.ru/product/ezhovik-korallovidnyy-700mg-molotyy-ezhevik-mitseliy-lions-mane-mikrodozing-1639925127/?tab=reviews&__rr=1&abt_att=1 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Mil’Fei. Available online: https://milfey-shop.ru/nativitan-nativitan-24 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Ozon. Available online: https://www.ozon.ru/product/kontsentrat-pishchevoy-na-osnove-rastitelnogo-syrya-batel-fungosbor-stimuliruyushchiy-pri-1315807345/?at=79tn7Yw8Yf4wWgLkugN3lo7Fkz6rxRfrZzy63H0Kq4rW (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Ozon. Available online: https://www.ozon.ru/product/ezhovik-grebenchatyy-ezhevik-korallovidnyy-izviliny-mitseliy-100-gramm-1761031816/?at=Brtz2NywNtrXJ7jLTE5vNjOfn23XlyS96XPY0i017v5q (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Fang, X.; Song, J.; Zhou, K.; Zi, X.; Sun, B.; Bao, H.; Li, L. Molecular Mechanism Pathways of Natural Compounds for the Treatment of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Molecules 2023, 28, 5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Li, M.H.; Yao, T.T.; Yi, X.J.; Gao, H.N. Research progress on AMPK in the pathogenesis and treatment of MASLD. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1558041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Ye, Y.; Shi, M.; Wang, X.; Cao, L.; Wang, L. Polysaccharides in Medicinal and Food Homologous Plants regulate intestinal flora to improve type 2 diabetes: Systematic review. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2024, 134, 156027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassir, F. NAFLD: Mechanisms, Treatments, and Biomarkers. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luan, H.; Duan, Z.; Ai, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, P. Efficacy of flavonoids in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1660065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezhilarasan, D.; Lakshmi, T. A Molecular Insight into the Role of Antioxidants in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 9233650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Yang, S.; Li, W.; Zheng, B.; Zeng, S.; Chen, H. Hericium erinaceus Protein Alleviates High-Fat Diet-Induced Hepatic Lipid Accumulation and Oxidative Stress In Vivo. Foods 2025, 14, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shi, J.; Shi, L. Natural products intervene in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by regulating the AMPK signaling pathway: Preclinical evidence and mechanism. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1696506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, L.; Merat, S.; Malekzadeh, R.; Nasseri-Moghaddam, S.; Aramin, H. Statins for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 12, CD008623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowis, D.; Malenda, A.; Furs, K.; Oleszczak, B.; Sadowski, R.; Chlebowska, J.; Firczuk, M.; Bujnicki, J.M.; Staruch, A.D.; Zagozdzon, R.; et al. Statins impair glucose uptake in human cells. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2014, 2, e000017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolivo, D.M.; Reed, C.R.; Gargiulo, K.A.; Rodrigues, A.E.; Galiano, R.D.; Mustoe, T.A.; Hong, S.J. Anti-fibrotic effects of statin drugs: A review of evidence and mechanisms. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 214, 115644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.; Nie, C.; Shi, Y.; Qiao, Q.; Gao, J.; Zou, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Hou, X. Ergothioneine ameliorates metabolic dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) by enhancing autophagy, inhibiting oxidative damage and inflammation. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, I.K.; Tang, R.; Ye, P.; Yew, T.S.; Lim, K.H.; Halliwell, B. Liver ergothioneine accumulation in a guinea pig model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. A possible mechanism of defence? Free Radic. Res. 2016, 50, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contato, A.G.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Lion’s Mane Mushroom (Hericium erinaceus): A Neuroprotective Fungus with Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antimicrobial Potential—A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fungus | Metabolite | Biological Activity | Model Object | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. erinaceus | Polysaccharide PHEB | Mitigating oxidative stress in the brain in Alzheimer’s disease by regulating Nrf2 and kinase; regulating calcium homeostasis in the brain; exhibiting anti-Alzheimer’s properties. PHEB polysaccharides ameliorate metabolic disorders (improving gut microbiota, reducing inflammation, and decreasing metabolic markers), which is associated with mechanisms relevant to NAFLD, including modulation of gut microbiota and regulation of metabolites, ultimately improving liver function via the gut–liver axis. | Laying hens | [19,44] |

| H. erinaceus | Heteropolysaccharides fraction HEP-W | Immunomodulatory activity. | Human cell lines | [45] |

| H. erinaceus | Polysaccharide HEFP | Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity; alleviating ulcerative colitis by inhibiting the NLRP3/caspase-1 inflammasome pathway. | Mouse | [46] |

| H. coralloides | Corallocins | Promoting the expression of nerve growth factor (NGF) in astrocytoma cells and neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells; stimulating the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). | Human cell lines | [36] |

| H. erinaceus | Erinacerins | Inhibiting effect on α-glycosidases (potential antidiabetic agents) and tyrosine phosphatase-1B (PTP1B); immunomodulatory and neuroprotective properties. | Human cell lines | [47] |

| H. flagellum | Hercioic and hericiofuranic acids | Neurotrophic activity. | Human and rat cell lines | [48] |

| H. erinaceus | Aromatic compounds: hericerin A, isohericenone J, isoericerin, hericerin, N-De phenylethyl isohericerin, hericenon J, 4-[3′,7′-dimethyl-2′,6′-octadienyl]-2-formyl-3-hydroxy-5-methoxybenzyl alcohol | Anticancer and neurotrophic activity. | Human cell lines | [43] |

| H. erinaceus | Erinacins | Neurotrophic activity; stimulating effect on the nerve growth factor (NGF) | Rat of the Wistar line | [49] |

| H. erinaceus, H. coralloides, H. americanum | Lovastatin | Anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and anticancer effects | Human cell lines | [50] |

| H. erinaceus, H. coralloides, H. americanum | Ergothioneine | Antioxidant, antiradiation, and anti-inflammatory activity | Review article | [51] |

| H. alpestre | Avenacin Y | Anticancer activity | Human cell lines | [52] |

| Product | Form | Active Ingredient | Biological Activity | Producer | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorbiotic (dietary supplement) | Concentrate | H. coralloides | Detoxifying effect, restoring intestinal microflora | Art Life, Russia | [55] |

| Ezhovik korallovidny (dietary supplement) | Capsules | H. coralloides dried mycelium | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunoregulatory activity | BIOFARM, Russia | [56] |

| Nativitan (dietary supplement) | Syrup | H. coralloides | Maintaining strong immunity and cognitive functions, increasing productivity; antitumor and anti-aging effects | Milfey, Germany | [57] |

| Fungosbor (dietary concentrate) | Capsules | H. coralloides extract | Stimulating effect in people with chronic fatigue | Batel, Russia | [58] |

| Ezhovik korallovidny + Ezhovik grebenchaty (dietary supplement) | Powder | H. coralloides mycelium | Neuroprotective, antiviral, immunomodulatory, and antitumor effects | Izviliny, Russia | [59] |

| Metabolite | Evidence Directly Related to NAFLD | Indirect or Supportive Metabolic Evidence | Hypothetical or Extrapolative Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharide PHEB | – | PHEB polysaccharides ameliorate metabolic disorders (including improvement of the gut microbiota and reductions in inflammation and metabolic markers), which is associated with mechanisms relevant to NAFLD, namely modulation of the gut microbiota and regulation of metabolites, leading to improved liver function via the gut–liver axis. The model object is laying hens [19] | Possible suppression of lipogenesis via AMPK activation and enhanced β-oxidation, as AMPK inhibits key lipogenic enzymes and promotes fatty acid oxidation. The model object is a human cell line [60] |

| Heteropolysaccharides fraction HEP-W | – | – | HEP-C from Hericium erinaceus ameliorated hyperglycemia and oxidative stress in diabetic rats, via activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, leading to improved glucose metabolism. The model object is a rat [60] |

| Polysaccharide HEFP | – | – | It enhances antioxidant defense and attenuates NF-κB–mediated inflammation, while AMPK can suppress NF-κB signaling and thereby reduce the inflammatory response. The model object is a mouse [61] Polysaccharides can reduce blood glucose levels and improve insulin sensitivity in diabetic models by increasing short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) levels and modulating immune-related signaling pathways, including PI3K/Akt and GLP-1. The model object is a mouse [62] |

| Corallocins | – | – | Antioxidant mechanisms, including the reduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), may safeguard against oxidative stress, a key contributor to NAFLD pathogenesis by promoting mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation. The model object is a human cell line [63] |

| Erinacerins | – | Compounds associated with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects may help improve systemic inflammation, which drives metabolic disorders, with similar effects observed in other models of inflammation. The model object is a mouse [46] | The anti-inflammatory effects may attenuate NF-κB–mediated cytokine production, thereby mitigating inflammatory processes that contribute to NAFLD progression. The model object is a rat [60] |

| Hercioic and hericiofuranic acids | – | Bioactive aromatic compounds derived from mushrooms have demonstrated antioxidant activity in in vitro studies, which may contribute to their metabolic effects relevant to NAFLD [64] | Antioxidant actions may strengthen the liver’s antioxidant system, reducing ROS-mediated damage and fibrosis. The model object is a human cell line [65] |

| Aromatic compounds: hericerin A, isohericenone J, isoericerin, hericerin, N-De phenylethyl isohericerin, hericenon J, 4-[3′,7′-dimethyl-2′,6′-octadienyl]-2-formyl-3-hydroxy-5-methoxybenzyl alcohol | – | – | Anticancer and neurotrophic activity. The model object is a human cell line [43] |

| Erinacins | – | Erinacines have been shown in high-fat diet–fed mice to reduce body weight, improve insulin resistance, and normalize blood glucose levels, indicating their potential in regulating metabolic disorders and obesity. The model object is a mouse [66] | Activation of AMPK can result in the downregulation of SREBP-1c and ACC, suppression of lipogenesis, promotion of β-oxidation, and stimulation of lipid droplet autophagy (lipophagy). The model object is a human cell line [67] |

| Lovastatin | Clinical and review literature is available on statins in NAFLD, including lovastatin as an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor. The model object is a human [68] | Lovastatin reduces glucose uptake in cells, as observed in human cell cultures, where glucose transport into cells decreased following lovastatin treatment. This effect may indicate an influence on glucose metabolism and insulin-dependent processes. The model object is a human cell line [69] | Statins may modulate inflammatory pathways and NF-κB signaling, thereby reducing the progression of fibrosis. Model objects of mice and rats [70] |

| Ergothioneine | In a MASLD model, ergothioneine reduced hepatic steatosis and inflammation in vivo (mice). The model object is a mouse [71] | In NAFLD and MASLD models, ergothioneine has demonstrated antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, mitigating oxidative stress, enhancing lipid metabolic profiles, and preventing the worsening of metabolic outcomes. The model object is guinea pig cell lines [72] | Antioxidant activity can safeguard mitochondria from ROS-induced damage and attenuate inflammation, both of which are critical contributors to NAFLD progression. The model object is a human cell line [65] |

| Avenacin Y | – | – | Saponins can indirectly modulate the microbiota and barrier function of the intestine, affecting systemic inflammation and lipid metabolism associated with NAFLD. The model object is a human cell line [63] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chekushkina, D.; Kozlova, O.; Vechtomova, E.; Prosekov, A. Dietary Use of Hericium coralloides for NAFLD Prevention. Nutrients 2026, 18, 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030418

Chekushkina D, Kozlova O, Vechtomova E, Prosekov A. Dietary Use of Hericium coralloides for NAFLD Prevention. Nutrients. 2026; 18(3):418. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030418

Chicago/Turabian StyleChekushkina, Darya, Oksana Kozlova, Elena Vechtomova, and Alexander Prosekov. 2026. "Dietary Use of Hericium coralloides for NAFLD Prevention" Nutrients 18, no. 3: 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030418

APA StyleChekushkina, D., Kozlova, O., Vechtomova, E., & Prosekov, A. (2026). Dietary Use of Hericium coralloides for NAFLD Prevention. Nutrients, 18(3), 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030418