Maternal Protein Restriction and Branched-Chain Amino Acid Supplementation Differentially Affect Maternal Energy Balance and Impair Offspring Growth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Housing, and Diets

2.2. Food Intake, Respiratory Quotient, and Energy Expenditure

2.3. Body Weight, Intraperitoneal Glucose, and Insulin Tolerance Tests

2.4. Computed Tomography Scan

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

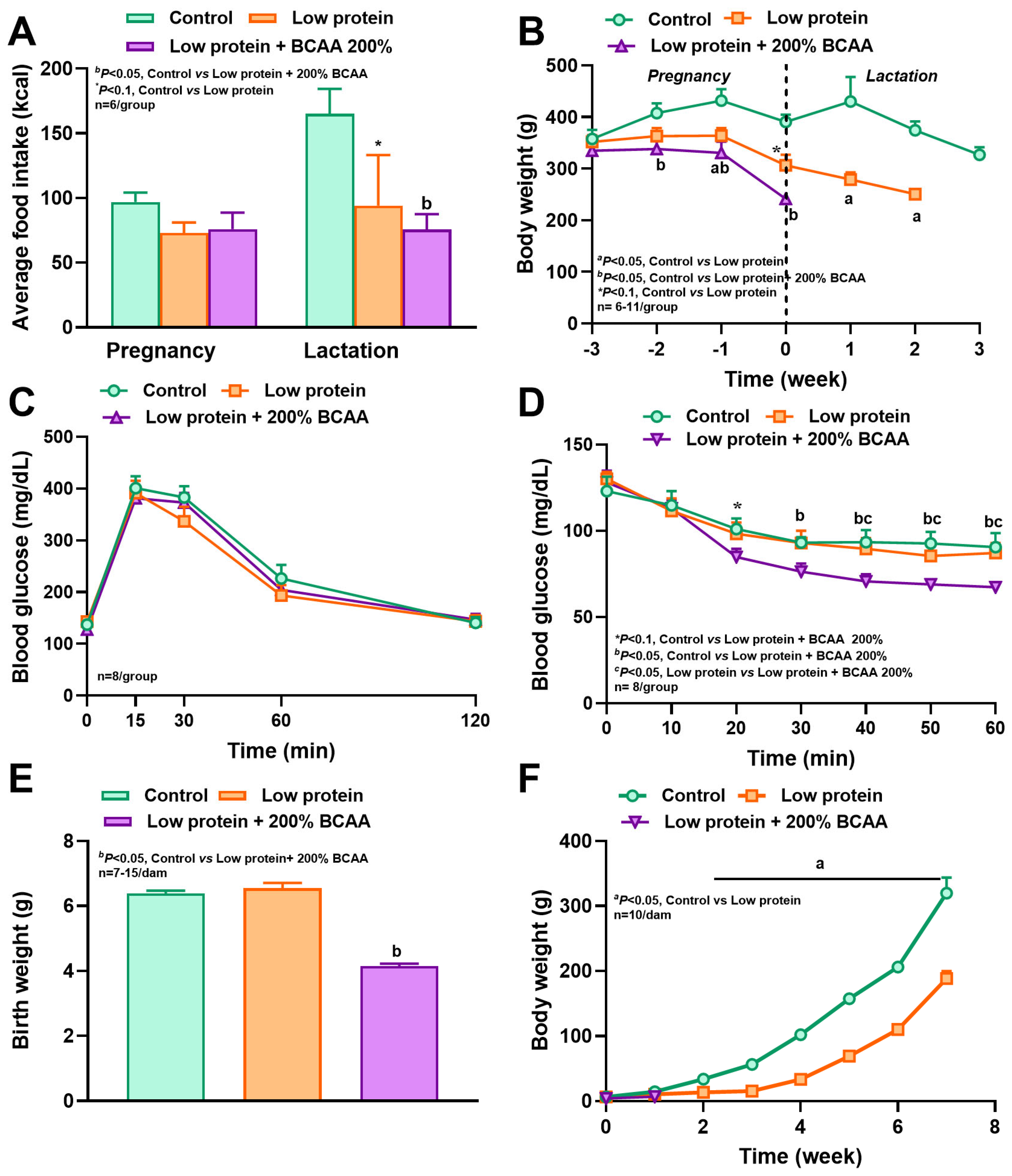

3.1. Maternal Protein Restriction and Branch Amino Acid Supplementation Alter Food Intake, Energy Expenditure, and Respiratory Quotient During Pregnancy and Lactation

3.2. Maternal Protein Restriction and BCAA Supplementation Reduced Body Weight, and BCAA Supplementation Increased Insulin Sensitivity

3.3. Maternal BCAA Supplementation to Low-Protein Diets Reduced Litter Size and Offspring Survival

3.4. Maternal Protein Restriction Affected Offspring Body Weight and Reduced Craniofacial Bone Dimensions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Marshall, N.E.; Abrams, B.; Barbour, L.A.; Catalano, P.; Christian, P.; Friedman, J.E.; Hay, W.W., Jr.; Hernandez, T.L.; Krebs, N.F.; Oken, E. The importance of nutrition in pregnancy and lactation: Lifelong consequences. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 607–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deputy, N.P.; Sharma, A.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Hinkle, S.N. Prevalence and characteristics associated with gestational weight gain adequacy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 125, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterman, M.J.K.; Hamilton, B.E.; Martin, J.A.; Driscoll, A.K.; Valenzuela, C.P.; Division of Vital Statistics. Births: Final Data for 2021; National Vital Statistics Reports; SERVICES USDOHAH: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Volume 72, p. 512021:31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekela, M.B.; Shimbre, M.S.; Gebabo, T.F.; Geta, M.B.; Tonga, A.T.; Zeleke, E.A.; Sidemo, N.B.; Getnet, A.B. Determinants of Low Birth Weight among Newborns Delivered at Public Hospitals in Sidama Zone, South Ethiopia: Unmatched Case-Control Study. J. Pregnancy 2020, 2020, 4675701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, A.K. Maternal Characteristics and Infant Outcomes by Hispanic Subgroup and Nativity: United States, 2021. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. Natl. Cent. Health Stat. 2023, 72, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll, A.K.; Gregory, E.C.W. Prepregnancy body mass index and infant outcomes by race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2020. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. Natl. Cent. Health Stat. 2021, 70, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Osterman, M.J.K.; Hamilton, B.E.; Martin, J.A.; Driscoll, A.K.; Valenzuela, C.P. Births: Final Data for 2022. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. Natl. Cent. Health Stat. 2024, 73, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Moullé, V.S.; Frapin, M.; Amarger, V.; Parnet, P. Maternal protein restriction in rats alters postnatal growth and brain lipid sensing in female offspring. Nutrients 2023, 15, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Sólis, R.; de Souza, S.L.; Matos, R.J.B.; Grit, I.; Le Bloch, J.; Nguyen, P.; de Castro, R.M.; Bolaños-Jiménez, F. Perinatal undernutrition-induced obesity is independent of the developmental programming of feeding. Physiol. Behav. 2009, 96, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinger, L.; Sculley, D.; Langley-Evans, S. Exposure to undernutrition in fetal life determines fat distribution, locomotor activity and food intake in ageing rats. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupe, B.; Grit, I.; Hulin, P.; Randuineau, G.; Parnet, P. Postnatal growth after intrauterine growth restriction alters central leptin signal and energy homeostasis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagisz, M.; Blair, H.; Kenyon, P.; Uller, T.; Raubenheimer, D.; Nakagawa, S. Transgenerational effects of caloric restriction on appetite: A meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, R.J.; Yablonski, E.; Li, J.; Tang, H.M.; Pontiggia, L.; D’Mello, A.P. Elucidation of thrifty features in adult rats exposed to protein restriction during gestation and lactation. Physiol Behav 2012, 105, 1182–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, Z. Maternal protein restriction induces early-onset glucose intolerance and alters hepatic genes expression in the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor pathway in offspring. J. Diabetes Investig. 2015, 6, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.G.; Beall, M.H. Adult sequelae of intrauterine growth restriction. In Seminars in Perinatology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Calsa, B.; Bortolança, T.J.; Masiero, B.C.; Esquisatto, M.A.M.; de Oliveira, C.A.; Catisti, R.; Santamaria, M., Jr. Maxillary and dental development in the offspring of protein-restricted female rats. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2022, 130, e12895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabrizio, V.; Trzaski, J.M.; Brownell, E.A.; Esposito, P.; Lainwala, S.; Lussier, M.M.; Hagadorn, J.I. Individualized versus standard diet fortification for growth and development in preterm infants receiving human milk. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 11, CD013465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmond, K.; Strobel, N. Evidence for Global Health Care Interventions for Preterm or Low Birth Weight Infants: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022057092C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azhar, M.; Yasin, R.; Hanif, S.; Bughio, S.A.; Das, J.K.; Bhutta, Z.A. Nutritional Management of Low Birth Weight and Preterm Infants in Low- and Low Middle-Income Countries. Neonatology 2025, 122, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.K.; Singhal, A.; Vaidya, U.; Banerjee, S.; Anwar, F.; Rao, S. Optimizing Nutrition in Preterm Low Birth Weight Infants-Consensus Summary. Front. Nutr. 2017, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partap, U.; Chowdhury, R.; Taneja, S.; Bhandari, N.; De Costa, A.; Bahl, R.; Fawzi, W. Preconception and periconception interventions to prevent low birth weight, small for gestational age and preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e007537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knibiehler, M.; Howard, S.P.; Baty, D.; Geli, V.; Lloubes, R.; Sauve, P.; Lazdunski, C. Isolation and molecular and functional properties of the amino-terminal domain of colicin A. Eur. J. Biochem. 1989, 181, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Patro, N.; Patro, I.K. Amelioration of neurobehavioral and cognitive abilities of F1 progeny following dietary supplementation with Spirulina to protein malnourished mothers. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 85, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillycrop, K.A.; Rodford, J.; Garratt, E.S.; Slater-Jefferies, J.L.; Godfrey, K.M.; Gluckman, P.D.; Hanson, M.A.; Burdge, G.C. Maternal protein restriction with or without folic acid supplementation during pregnancy alters the hepatic transcriptome in adult male rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1711–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogami, H.; Yura, S.; Itoh, H.; Kawamura, M.; Fujii, T.; Suzuki, A.; Aoe, S.; Ogawa, Y.; Sagawa, N.; Konishi, I.; et al. Isocaloric high-protein diet as well as branched-chain amino acids supplemented diet partially alleviates adverse consequences of maternal undernutrition on fetal growth. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2009, 19, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baysal, B.; Micili, S.; Engur, D.; Akokay, P.; Karabulut, A.R.; Keskinoglu, P.; Yilmaz, O.; Kumral, A. Impact of postnatal nutrition on neurodevelopmental outcome in rat model of intrauterine growth restriction. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 7498–7505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Marchand, K.; Lam, L.; Lux-Lantos, V.; Thyssen, S.M.; Guo, J.; Giacca, A.; Arany, E. Maternal taurine supplementation in rats partially prevents the adverse effects of early-life protein deprivation on beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity. Reproduction 2013, 145, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, S.S.; Koh, J.S.; Jin, C.J.; Park, S.H.; Yi, K.H.; Park, K.S.; Lee, H.K. Taurine supplementation restored the changes in pancreatic islet mitochondria in the fetal protein-malnourished rat. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scabora, J.E.; de Lima, M.C.; Lopes, A.; de Lima, I.P.; Mesquita, F.F.; Torres, D.B.; Boer, P.A.; Gontijo, J.A. Impact of taurine supplementation on blood pressure in gestational protein-restricted offspring: Effect on the medial solitary tract nucleus cell numbers, angiotensin receptors, and renal sodium handling. J. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2015, 16, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.A.; Dunn, R.L.; Marchand, M.C.; Langley-Evans, S.C. Increased systolic blood pressure in rats induced by a maternal low-protein diet is reversed by dietary supplementation with glycine. Clin. Sci. 2002, 103, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, A.; Parnet, P.; Nowak, C.; Tran, N.T.; Winer, N.; Darmaun, D. L-Citrulline Supplementation Enhances Fetal Growth and Protein Synthesis in Rats with Intrauterine Growth Restriction. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Bi, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, J. Association of circulating branched-chain amino acids with gestational diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 17, e85413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Liang, S.; Guo, C.; Ma, X.; Li, G. Dynamic changes and early predictive value of branched-chain amino acids in gestational diabetes mellitus during pregnancy. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1000296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhasin, K.K.; van Nas, A.; Martin, L.J.; Davis, R.C.; Devaskar, S.U.; Lusis, A.J. Maternal low-protein diet or hypercholesterolemia reduces circulating essential amino acids and leads to intrauterine growth restriction. Diabetes 2009, 58, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.; Kim, J.; Ko, J.W.; Choi, A.; Kwon, Y.H. Effects of maternal branched-chain amino acid and alanine supplementation on growth and biomarkers of protein metabolism in dams fed a low-protein diet and their offspring. Amino Acids 2022, 54, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, G.F.; Vianna, D.; Torres-Leal, F.L.; Pantaleao, L.C.; Matos-Neto, E.M.; Donato, J., Jr.; Tirapegui, J. Leucine is essential for attenuating fetal growth restriction caused by a protein-restricted diet in rats. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudet, L.; Ferraro, Z.M.; Wen, S.W.; Walker, M. Maternal obesity and occurrence of fetal macrosomia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 640291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, P.G.; Nielsen, F.H.; Fahey, G.C., Jr. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: Final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J. Nutr. 1993, 123, 1939–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avirineni, B.S.; Singh, A.; Zapata, R.C.; Stevens, R.D.; Phillips, C.D.; Chelikani, P.K. Diets Containing Egg or Whey Protein and Inulin Fiber Improve Energy Balance and Modulate Gut Microbiota in Exercising Obese Rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, e2100653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezeshki, A.; Zapata, R.C.; Singh, A.; Yee, N.J.; Chelikani, P.K. Low protein diets produce divergent effects on energy balance. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, R.C.; Singh, A.; Pezeshki, A.; Avirineni, B.S.; Patra, S.; Chelikani, P.K. Low-Protein Diets with Fixed Carbohydrate Content Promote Hyperphagia and Sympathetically Mediated Increase in Energy Expenditure. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1900088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Pezeshki, A.; Zapata, R.C.; Yee, N.J.; Knight, C.G.; Tuor, U.I.; Chelikani, P.K. Diets enriched in whey or casein improve energy balance and prevent morbidity and renal damage in salt-loaded and high-fat-fed spontaneously hypertensive stroke-prone rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 37, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plagemann, A.; Harder, T.; Rake, A.; Melchior, K.; Rohde, W.; Dörner, G. Hypothalamic nuclei are malformed in weanling offspring of low protein malnourished rat dams. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 2582–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.P.; German, R.Z. Protein malnutrition affects the growth trajectories of the craniofacial skeleton in rats. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 2061–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, C.; Macêdo, G.; Latorraca, M.; Arantes, V.; Veloso, R.; Carneiro, E.; Boschero, A.; Nascimento, C.; Gaíva, M. Serum leptin and insulin levels in lactating protein-restricted rats: Implications for energy balance. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 97, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, A.; Mayntz, D.; Raubenheimer, D.; Simpson, S.J. Protein-leverage in mice: The geometry of macronutrient balancing and consequences for fat deposition. Obesity 2008, 16, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quek, V.; Trayhurn, P. Calorimetric study of the energetics of pregnancy in golden hamsters. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1990, 259, R807–R812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, R.J.; Li, J.; Tang, H.M.; Pontiggia, L.; D’Mello, A.P. Maternal protein restriction during pregnancy and lactation alters central leptin signalling, increases food intake, and decreases bone mass in 1 year old rat offspring. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2016, 43, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretto, V.L.; Ballen, M.O.; Gonçalves, T.S.; Kawashita, N.H.; Stoppiglia, L.F.; Veloso, R.V.; Latorraca, M.Q.; Martins, M.S.F.; Gomes-da-Silva, M.H.G. Low-Protein Diet during Lactation and Maternal Metabolism in Rats. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2011, 2011, 876502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supruniuk, E.; Żebrowska, E.; Chabowski, A. Branched chain amino acids—Friend or foe in the control of energy substrate turnover and insulin sensitivity? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 2559–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allman, B.R.; Diaz, E.C.; Andres, A.; Børsheim, E. Divergent changes in serum branched-chain amino acid concentrations and estimates of insulin resistance throughout gestation in healthy women. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allman, B.R.; Spray, B.J.; Mercer, K.E.; Andres, A.; Børsheim, E. Markers of branched-chain amino acid catabolism are not affected by exercise training in pregnant women with obesity. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 130, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, N.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhong, M.; Cui, D.; Chai, O.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hou, Z. Correlation between newborn weight and serum BCAAs in pregnant women with diabetes. Nutr. Diabetes 2024, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, A.; Rema, V.; Jain, N. Prenatal protein deficiency causes age-specific alteration in number and distribution of inhibitory neurons in the somatosensory cortex during early postnatal development. J. Biosci. 2025, 50, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, M.S. The Emerging Role of Branched-Chain Amino Acids in Insulin Resistance and Metabolism. Nutrients 2016, 8, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, A.; Wenner, B.R.; Ilkayeva, O.; Stevens, R.D.; Maggioni, M.; Slotkin, T.A.; Levin, E.D.; Newgard, C.B. Branched-chain amino acids alter neurobehavioral function in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 304, e405–e413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, T.; Swart, J.M.; Grattan, D.R.; Brown, R.S.E. The Prolactin Family of Hormones as Regulators of Maternal Mood and Behavior. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2021, 2, 767467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairenji, T.J.; Ikezawa, J.; Kaneko, R.; Masuda, S.; Uchida, K.; Takanashi, Y.; Masuda, H.; Sairenji, T.; Amano, I.; Takatsuru, Y.; et al. Maternal prolactin during late pregnancy is important in generating nurturing behavior in the offspring. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 13042–13047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarôco, G.; de Genova Gaya, L.; Resende, D.R.; dos Santos, I.C.; Madureira, A.P. Environmental and dam effects on cannibalism in Wistar rat litters. Acta Scientiarum. Biol. Sci. 2015, 37, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.M.; Abreu, A.V.; Silva, R.B.; Silva, D.F.; Martinez, G.L.; Babinski, M.A.; Ramos, C.F. Maternal malnutrition during lactation reduces skull growth in weaned rat pups: Experimental and morphometric investigation. Anat. Sci. Int. 2008, 83, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.R.; Silva, G.A.; Fiúza, A.T.; Chianca, D.A., Jr.; Ferreira, A.J.; Chiarini-Garcia, H. Gestational and postnatal protein deficiency affects postnatal development and histomorphometry of liver, kidneys, and ovaries of female rats’ offspring. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 37, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, K.; Kondo, T.; Nagai, H.; Mino, M.; Takeshita, A.; Okada, T. Maternal protein restriction that does not have an influence on the birthweight of the offspring induces morphological changes in kidneys reminiscent of phenotypes exhibited by intrauterine growth retardation rats. Congenit. Anom. 2016, 56, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwuoke, W.I.; Igwebuike, U.M.; Igbokwe, C.O. The effects of maternal dietary protein restriction during gestation in rats on postnatal growth of the body and internal organs of the offspring. Anim. Res. Int. 2020, 17, 3596–3602. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Valverde, D.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, P.; Gutierrez-Arzapalo, P.; De Pablo, A.L.; González, M.C.; López-Giménez, R.; Somoza, B.; Arribas, S. Effect of fetal undernutrition and postnatal overfeeding on rat adipose tissue and organ growth at early stages of postnatal development. Physiol. Res. 2015, 64, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- do Nascimento, E.; da Luz Neto, L.M.; de Morais Araújo, N.C.; de Souza Franco, E.; de Santana Muniz, G. Consequences on anthropometry and metabolism of offspring maintenance with low-protein diet since pregnancy to adult age Consequências sobre a antropometria eo metabolismo em ratos submetidos a dieta com baixo teor de proteínas da gravidez até a idade adulta. Braz. J. Health Rev. 2022, 5, 13111–13129. [Google Scholar]

- Terstappen, F.; Tol, A.J.C.; Gremmels, H.; Wever, K.E.; Paauw, N.D.; Joles, J.A.; Beek, E.M.V.; Lely, A.T. Prenatal Amino Acid Supplementation to Improve Fetal Growth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucciarelli, H.M.; Oyhenart, E.E. Effects of maternal food restriction during lactation on craniofacial growth in weanling rats. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1987, 72, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study 1 | Study 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredients | CON | LP | LP + 100% BCAA | CON | LP | LP + 200% BCAA |

| Corn oil | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Lard | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 |

| Casein | 230 | 55 | 55 | 230 | 35 | 35 |

| Corn starch | 315.7 | 490.7 | 456.7 | 315.7 | 428.7 | 428.7 |

| Sucrose | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Fructose | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| α-Cellulose | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| AIN-93G-MX mineral mix | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| AIN-93-VX vitamin mix | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| L-Cysteine | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Choline bitartrate | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| tert-Butylhydroquinone (TBHQ) | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| Leu | 15.4 | 37.7 | ||||

| Ala | 82.28 | |||||

| Ile | 8.3 | 20.33 | ||||

| Val | 9.9 | 24.25 | ||||

| Total amount (g) | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| Casein AA profile | ||||||

| Leu | 20.24 | 4.84 | 4.84 | 20.24 | 3.08 | 3.08 |

| Arg | 8.28 | 1.98 | 1.98 | 8.28 | 1.26 | 1.26 |

| Asp | 14.95 | 3.575 | 3.575 | 14.95 | 2.275 | 2.275 |

| Glu | 47.84 | 11.44 | 11.44 | 47.84 | 7.28 | 7.28 |

| His | 5.98 | 1.43 | 1.43 | 5.98 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| Met | 5.98 | 1.43 | 1.43 | 5.98 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| Phe | 11.5 | 2.75 | 2.75 | 11.5 | 1.75 | 1.75 |

| Thr | 8.74 | 2.09 | 2.09 | 8.74 | 1.33 | 1.33 |

| Trp | 2.76 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 2.76 | 0.42 | 0.42 |

| Ala | 5.98 | 1.43 | 1.43 | 5.98 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| Cys | 0.92 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.92 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| Gly | 4.14 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 4.14 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| Ile | 11.04 | 2.64 | 2.64 | 11.04 | 1.68 | 1.68 |

| Lys | 17.02 | 4.07 | 4.07 | 17.02 | 2.59 | 2.59 |

| Pro | 26.91 | 6.435 | 6.435 | 26.91 | 4.095 | 4.095 |

| Ser | 12.42 | 2.97 | 2.97 | 12.42 | 1.89 | 1.89 |

| Tyr | 12.19 | 2.915 | 2.915 | 12.19 | 1.855 | 1.855 |

| Val | 13.11 | 3.135 | 3.135 | 13.11 | 1.995 | 1.995 |

| Composition | ||||||

| Protein (% Kcal) | 20% | 5% | 8% | 20% | 10% | 10% |

| Carbohydrate (% Kcal) | 40% | 55% | 52% | 40% | 50% | 50% |

| Fat (% Kcal) | 40% | 40% | 40% | 40% | 40% | 40% |

| Total calories/g | 4.63 | 4.63 | 4.63 | 4.63 | 4.63 | 4.63 |

| Study 1 | |||

| Control | LP | LP + 100%BCAA | |

| Successful pregnancies (%) | 50 | 18.18 | 27.27 |

| Litter size | 14.5 | 14.5 | 11 * |

| Pups born alive (%) | 98.28 | 96.55 | 100 |

| Pups born dead (%) | 1.75 | 3.45 | 0 |

| Pup survival until weaning (%) | 94.83 | 96.55 | 54.55 b |

| Cannibalism (mothers%) | 0 | 0 | 33.33 |

| Study 2 | |||

| Control | LP | LP + 200%BCAA | |

| Successful pregnancies (%) | 75 | 50 | 75 |

| Litter size | 13.66 | 7 a | 11.16 * |

| Pups born alive (%) | 100 | 100 | 86.57 b |

| Pups born dead (%) | 0 | 0 | 13.43 b |

| Pup survival until weaning (%) | 89.02 | 90.48 | 0.0 b |

| Cannibalism (mothers%) | 16.67 | 0 | 83.33 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Redrovan, D.; Patra, S.; Aziz, M.T.; Gorton, M.W.; Chavez, E.A.; Frederiksen, S.; Rowe, J.; Pezeshki, A.; Chelikani, P.K. Maternal Protein Restriction and Branched-Chain Amino Acid Supplementation Differentially Affect Maternal Energy Balance and Impair Offspring Growth. Nutrients 2026, 18, 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020322

Redrovan D, Patra S, Aziz MT, Gorton MW, Chavez EA, Frederiksen S, Rowe J, Pezeshki A, Chelikani PK. Maternal Protein Restriction and Branched-Chain Amino Acid Supplementation Differentially Affect Maternal Energy Balance and Impair Offspring Growth. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):322. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020322

Chicago/Turabian StyleRedrovan, Daniela, Souvik Patra, Md Tareq Aziz, Matthew W. Gorton, Emily A. Chavez, Scott Frederiksen, Joshua Rowe, Adel Pezeshki, and Prasanth K. Chelikani. 2026. "Maternal Protein Restriction and Branched-Chain Amino Acid Supplementation Differentially Affect Maternal Energy Balance and Impair Offspring Growth" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020322

APA StyleRedrovan, D., Patra, S., Aziz, M. T., Gorton, M. W., Chavez, E. A., Frederiksen, S., Rowe, J., Pezeshki, A., & Chelikani, P. K. (2026). Maternal Protein Restriction and Branched-Chain Amino Acid Supplementation Differentially Affect Maternal Energy Balance and Impair Offspring Growth. Nutrients, 18(2), 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020322