Real-World Evidence of Growth Improvement in Children 1 to 5 Years of Age Receiving Enteral Formula Administered Through an Immobilized Lipase Cartridge

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Study Data Collection

2.4. Study Endpoints

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Population

3.2. Enteral Nutrition and ILC Use

3.3. Patient Disposition

3.4. Efficacy Analysis

3.5. Safety Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CDC | US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CF | Cystic fibrosis |

| CFF | Cystic Fibrosis Foundation |

| CFTR | CF transmembrane conductance regulator |

| EN | Enteral nutrition |

| EPI | Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency |

| ETI | Elexacaftor, tezacaftor, and ivacaftor |

| FDA | US Food and Drug Administration |

| ILC | Immobilized lipase cartridge |

| NA | Not applicable |

| PERT | Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy |

| pwCF | People with cystic fibrosis |

| SBS | Short bowel syndrome |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| US | United States of America |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WSR | Wilcoxon signed-rank |

| yo | Year old |

References

- Omer, E.; Chiodi, C. Fat digestion and absorption: Normal physiology and pathophysiology of malabsorption, including diagnostic testing. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2024, 39, S6–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, T.I.; Wang, S.Z.; Fligor, S.C.; Quigley, M.; Gura, K.M.; Puder, M.; Tsikis, S.T. Fat malabsorption in short bowel syndrome: A review of pathophysiology and management. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2024, 39, S17–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzenberg, S.J.; Hempstead, S.E.; McDonald, C.M.; Powers, S.W.; Woolridge, J.; Blair, S.; Freedman, S.; Harrington, E.; Murphy, P.J.; Palmer, L.; et al. Enteral tube feeding for individuals with cystic fibrosis: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation evidence-informed guidelines. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2016, 15, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, A.; Mehta, D.; Horvath, K. A review of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in children beyond cystic fibrosis and the role of endoscopic direct pancreatic function testing. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2025, 27, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.J.; Maqbool, A.; Bellin, M.D.; Goldschneider, K.R.; Grover, A.S.; Hartzell, C.; Piester, T.L.; Szabo, F.; Kiernan, B.D.; Khalaf, R.; et al. Medical management of chronic pancreatitis in children: A position paper by the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Pancreas Committee. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 72, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RELiZORB Instructions for Use. Available online: https://www.relizorbhcp.com/pdf/RELiZORB-Instructions-for-Use.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Leonard, A.; Bailey, J.; Bruce, A.; Jia, S.; Stein, A.; Fulton, J.; Helmick, M.; Litvin, M.; Patel, A.; Powers, K.E.; et al. Nutritional considerations for a new era: A CF Foundation position paper. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2023, 22, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitcomb, D.C.; Buchner, A.M.; Forsmark, C.E. AGA clinical practice update on the Epidemiology, evaluation, and management of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, S.; Orenstein, D.; Black, P.; Brown, P.; McCoy, K.; Stevens, J.; Grujic, D.; Clayton, R. Increased fat absorption from enteral formula through an in-line digestive cartridge in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 65, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.; Wyatt, C.; Brown, P.; Patel, D.; Grujic, D.; Freedman, S.D. Absorption and safety with sustained use of RELiZORB evaluation (ASSURE) study in patients with cystic fibrosis receiving enteral feeding. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 67, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, S.J.; Flume, P.A.; First, E.R.; Stone, A.A.; Van Buskirk, M. Improvements in anthropometric measures and gastrointestinal tolerance in patients with cystic fibrosis by using a digestive enzyme cartridge with overnight enteral nutrition. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2022, 37, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghae Pour, P.; Gregg, S.; Coakley, K.E.; Caffey, L.C.; Cohen, D.; Myers, O.B.; Conzales-Pacheco, D. The use of the RELiZORB immobilized lipase cartridge in enterally-fed children with cystic fibrosis: A retrospective case series. Topics Clinical Nutr. 2022, 37, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathe, M.N.; Patel, D.; Stone, A.; First, E. Evaluation of the effectiveness of in-line immobilized lipase cartridge in enterally fed patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 72, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastava, S.; Shaw, K.; Lee, M.; Reitich, P.; Hunter, S.; Klosterman, M.; Sathe, M. Association of in-line digestive enzyme cartridge with enteral feeds on improvement in anthropometrics among pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2024, 39, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry 2023 Annual Data Report; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.cff.org/sites/default/files/2024-09/2023-Patient-Registry-Annual-Data-Report.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. Use of Real-World Evidence to Support Regulatory Decision-Making for Medical Devices-Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. 31 August 2017. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/files/medical%20devices/published/Use-of-Real-World-Evidence-to-Support-Regulatory-Decision-Making-for-Medical-Devices---Guidance-for-Industry-and-Food-and-Drug-Administration-Staff.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). SAS Program for CDC Growth Charts. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/growth-chart-training/hcp/computer-programs/sas.html (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). SAS Program for WHO Growth Charts. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/growth-chart-training/hcp/computer-programs/sas-who.html (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Mason, K.A.; Rogol, A.D. Trends in growth and maturation in children with cystic fibrosis throughout nine decades. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 935354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zysman-Colman, Z.N.; Kilberg, M.J.; Harrison, V.S.; Chesi, A.; Grant, S.F.A.; Mitchell, J.; Sheikh, S.; Hadjiliadis, D.; Rickels, M.R.; Rubenstein, R.C.; et al. Genetic potential and height velocity during childhood and adolescence do not fully account for shorter stature in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 89, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, T.; Hempstead, S.E.; Brady, C.; Cannon, C.L.; Clark, K.; Condren, M.E.; Guill, M.F.; Guillerman, R.P.; Leone, C.G.; Maguiness, K.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation for preschoolers with cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20151784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankararaman, S.; Schindler, T.; Sferra, T.J. Management of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in children. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2019, 34, S27–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soden, J.; Aarnio-Peterson, M.; Neal, J.; Recker, D.P.; Remmers, A.E. Development of a registry to evaluate immobilized lipase cartridge use in pediatric patients with short bowel syndrome/intestinal failure. Intest. Fail. 2024, 3, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikis, S.T.; Fligor, S.C.; Mitchell, P.D.; Hirsch, T.I.; Carbeau, S.; First, E.; Loring, G.; Rudie, C.; Freedman, S.D.; Martin, C.R.; et al. Fat digestion using RELiZORB in children with short bowel syndrome who are dependent on parenteral nutrition: Protocol for a 90-day, phase 3, open labeled study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, R.; Brownell, J.N.; Stallings, V.A. The impact of highly effective CFTR modulators on growth and nutrition status. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavrina, K.; Griffin, T.B.; Jones, A.M.; Schindler, T.; Bui, T.N.; Sankararaman, S. Evolving nutrition therapy in cystic fibrosis: Adapting to the CFTR modulator era. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2025, 40, 816–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenberg, S.J.; Vu, P.T.; Skalland, M.; Hoffman, L.R.; Pope, C.; Gelfond, D.; Narkewicz, M.R.; Nichols, D.P.; Heltshe, S.L.; Donaldson, S.H.; et al. Elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor and gastrointestinal outcomes in cystic fibrosis: Report of promise-GI. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2023, 22, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankararaman, S.; Prunty, L.; Pamer, C.; Thavamani, A.; Roesch, E.; Schindler, T. Impact of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor on fecal elastase-1 in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2025, 60, e71156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goralski, J.L.; Hoppe, J.E.; Mall, M.A.; McColley, S.A.; McKone, E.; Ramsey, B.; Rayment, J.H.; Robinson, P.; Stehling, F.; Taylor-Cousar, J.L.; et al. Phase 3 open-label clinical trial of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor in children aged 2 through 5 years with cystic fibrosis and at least one F508del allele. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 208, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, A.J.; Bilbo, A. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and pancreatic exocrine replacement therapy in clinical practice. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2024, 39, S78–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | All Patients (n = 186) | Efficacy Population (n = 143) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 100 (54%) | 76 (53%) |

| Female | 86 (46%) | 67 (47%) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.2) |

| Min, Max | 1.0, 4.99 | 1.0, 4.99 |

| Age, years, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 63 (34%) | 48 (34%) |

| 2 | 36 (19%) | 28 (20%) |

| 3 | 42 (23%) | 28 (20%) |

| 4 | 45 (24%) | 39 (27%) |

| Referral diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Cystic fibrosis (CF) | 128 (69%) | 109 (76%) |

| Other diagnosis * | 58 (31%) | 34 (24%) |

| Short bowel syndrome | 24 (13%) | 14 (10%) |

| Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in patients without a diagnosis of CF | 8 (4%) | 5 (4%) |

| Pancreatitis | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) |

| Failure to thrive | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Measure | All Patients (n = 186) | Efficacy Population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All 1- to 4-Year-Olds (n = 143) | 1-Year-Olds (n = 48) | 2- to 4-Year-Olds (n = 95) | |||

| Weight | n | 172 | 143 | 48 | 95 |

| CDC z-score | Mean (SD) | −1.6 (1.4) | −1.6 (1.3) | −2.3 (1.3) | −1.2 (1.2) |

| CDC percentile | Mean (SD) | 17.3 (22.3) | 16.7 (21.5) | 7.0 (12.8) | 21.6 (23.4) |

| Height | n | 166 | 139 | 47 | 92 |

| CDC z-score | Mean (SD) | −1.3 (1.5) | −1.2 (1.3) | −1.6 (1.4) | −1.1 (1.2) |

| CDC percentile | Mean (SD) | 23.1 (24.8) | 22.9 (24.4) | 17.4 (22.9) | 25.7 (24.9) |

| BMI | n | 105 | 90 | 47 | 90 |

| CDC z-score | Mean (SD) | −0.7 (1.2) | −0.7 (1.1) | NA | −0.7 (1.1) |

| CDC percentile | Mean (SD) | 31.7 (28.3) | 32.9 (27.6) | NA | 32.9 (27.6) |

| Weight-for-length | n | 47 | |||

| WHO z-score | Mean (SD) | NA | NA | −0.7 (1.0) | NA |

| WHO percentile | Mean (SD) | NA | NA | 30.8 (26.9) | NA |

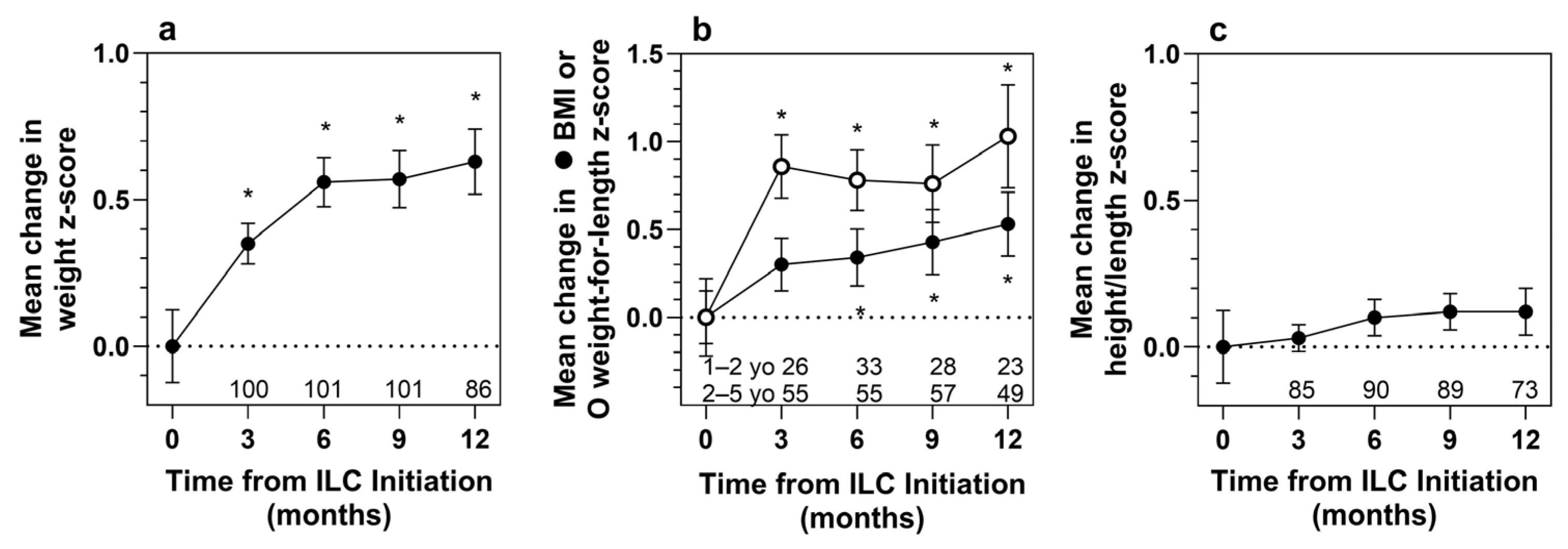

| Measure | Statistic | Months Following ILC Initiation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Months | 6 Months | 9 Months | 12 Months | ||

| Efficacy Population (n = 143) | |||||

| Weight | n | 100 | 101 | 101 | 86 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −1.58 (1.24) | −1.57 (1.34) | −1.57 (1.30) | −1.63 (1.42) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | −1.24 (1.19) | −1.01 (1.17) | −1.00 (1.17) | −1.01 (1.37) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | 0.35 (0.69) | 0.56 (0.85) | 0.57 (0.98) | 0.63 (1.03) |

| t-test p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| WSR p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Height | n | 85 | 90 | 89 | 73 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −1.13 (1.15) | −1.12 (1.22) | −1.07 (1.16) | −1.19 (1.33) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | −1.09 (1.11) | −1.02 (1.22) | −0.95 (1.15) | −1.07 (1.33) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | 0.03 (0.43) | 0.10 (0.59) | 0.12 (0.59) | 0.12 (0.69) |

| t-test p-value | 0.501 | 0.104 | 0.063 | 0.128 | |

| WSR p-value | 0.793 | 0.146 | 0.082 | 0.093 | |

| BMI (2 to 4 years old) | n | 55 | 55 | 57 | 49 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −0.70 (1.20) | −0.74 (1.07) | −0.82 (1.06) | −0.70 (1.12) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | −0.40 (1.18) | −0.40 (1.13) | −0.39 (1.11) | −0.18 (1.16) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | 0.30 (1.12) | 0.34 (1.20) | 0.43 (1.40) | 0.53 (1.28) |

| t-test p-value | 0.053 | 0.038 | 0.024 | 0.006 | |

| WSR p-value | 0.040 | 0.016 | 0.047 | 0.007 | |

| 1 year old (n = 48) | |||||

| Weight | n | 33 | 38 | 32 | 27 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −2.36 (1.19) | −2.31 (1.34) | −2.22 (1.23) | −2.55 (1.41) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | −1.73 (1.23) | −1.32 (1.20) | −1.11 (1.12) | −1.38 (1.55) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | 0.63 (0.63) | 0.99 (0.84) | 1.11 (0.88) | 1.17 (1.07) |

| t-test p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| WSR p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Height | n | 26 | 33 | 28 | 24 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −1.53 (1.23) | −1.53 (1.37) | −1.36 (1.16) | −1.58 (1.57) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | −1.51 (1.21) | −1.44 (1.30) | −1.01 (1.08) | −1.40 (1.79) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | 0.02 (0.53) | 0.09 (0.64) | 0.34 (0.70) | 0.18 (1.53) |

| t-test p-value | 0.858 | 0.418 | 0.015 | 0.397 | |

| WSR p-value | 0.853 | 0.511 | 0.015 | 0.419 | |

| Weight-for-length | n | 26 | 33 | 28 | 23 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −0.79 (1.13) | −0.59 (1.03) | −0.56 (1.09) | −0.90 (1.21) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | 0.07 (0.78) | 0.18 (1.02) | 0.20 (1.04) | 0.13 (0.87) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | 0.86 (0.92) | 0.78 (0.99) | 0.76 (1.17) | 1.03 (1.41) |

| t-test p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

| WSR p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | |

| 2 to 4 years old (n = 95) | |||||

| Weight | n | 67 | 63 | 69 | 59 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −1.20 (1.08) | −1.13 (1.13) | −1.27 (1.23) | −1.22 (1.22) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | −0.99 (1.10) | −0.83 (1.11) | −0.95 (1.19) | −0.84 (1.26) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | 0.21 (0.67) | 0.31 (0.76) | 0.32 (0.93) | 0.38 (0.92) |

| t-test p-value | 0.014 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.003 | |

| WSR p-value | 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.015 | 0.006 | |

| Height | n | 59 | 57 | 61 | 49 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −0.95 (1.08) | −0.88 (1.07) | −0.93 (1.14) | −1.01 (1.17) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | −0.91 (1.03) | −0.78 (1.10) | −0.92 (1.19) | −0.91 (1.01) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | 0.04 (0.39) | 0.11 (0.57) | 0.01 (0.50) | 0.10 (0.47) |

| t-test p-value | 0.465 | 0.153 | 0.840 | 0.153 | |

| WSR p-value | 0.841 | 0.211 | 0.818 | 0.285 | |

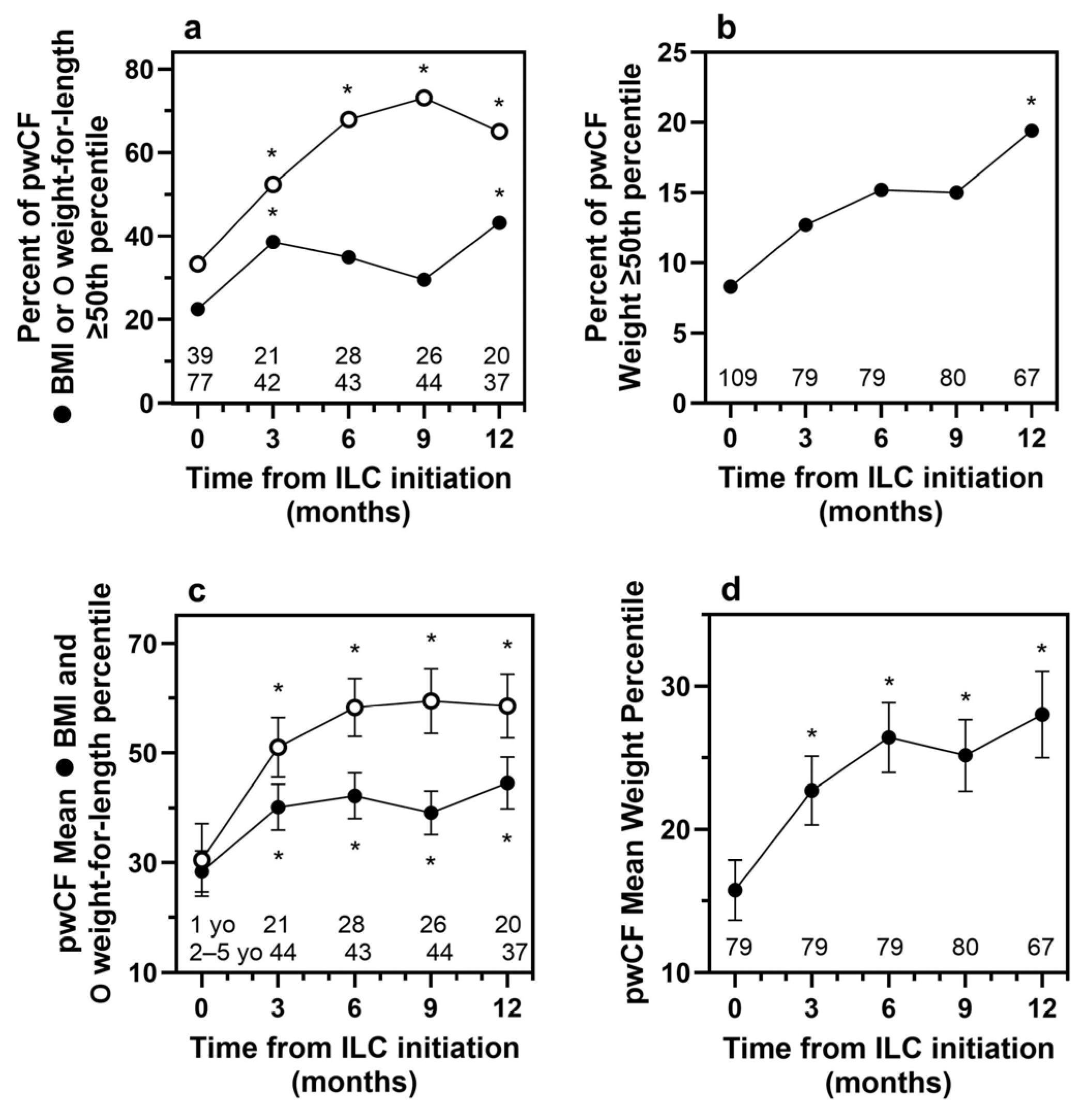

| Patients with Cystic Fibrosis (n = 109) | |||||

| Weight | n | 79 | 79 | 80 | 67 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −1.54 (1.19) | −1.46 (1.18) | −1.55 (1.19) | −1.55 (1.27) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | −1.11 (1.11) | −0.90 (1.05) | −0.95 (1.03) | −0.86 (1.07) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | 0.42 (0.58) | 0.56 (0.71) | 0.60 (0.98) | 0.69 (1.00) |

| t-test p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| WSR p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Height | n | 67 | 72 | 73 | 58 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −0.94 (1.04) | −0.91 (1.07) | −0.97 (1.05) | −0.96 (1.08) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | −0.95 (1.00) | −0.84 (1.03) | −0.85 (1.06) | −0.85 (1.03) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | 0 (0.37) | 0.07 (0.55) | 0.12 (0.59) | 0.11 (0.69) |

| t-test p-value | 0.965 | 0.289 | 0.095 | 0.252 | |

| WSR p-value | 0.725 | 0.358 | 0.095 | 0.260 | |

| BMI (2 to 4 years old) | n | 44 | 43 | 44 | 37 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −0.85 (1.10) | −0.80 (1.02) | −0.89 (1.07) | −0.75 (1.03) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | −0.36 (1.00) | −0.29 (0.97) | −0.39 (1.02) | −0.20 (0.96) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | 0.49 (0.91) | 0.51 (1.00) | 0.49 (1.35) | 0.55 (1.23) |

| t-test p-value | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.019 | 0.009 | |

| WSR p-value | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.005 | |

| Patients with an indication other than CF (n = 34) | |||||

| Weight | n | 21 | 22 | 21 | 19 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −1.75 (1.40) | −1.99 (1.76) | −1.62 (1.69) | −1.93 (1.85) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | −1.69 (1.40) | −1.41 (1.48) | −1.19 (1.60) | −1.53 (2.07) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | 0.06 (0.96) | 0.58 (1.26) | 0.43 (1.01) | 0.39 (1.14) |

| t-test p-value | 0.779 | 0.042 | 0.063 | 0.150 | |

| WSR p-value | 0.854 | 0.047 | 0.200 | 0.294 | |

| Height | n | 18 | 18 | 16 | 15 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −1.81 (1.34) | −1.98 (1.45) | −1.51 (1.51) | −2.12 (1.80) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | −1.65 (1.35) | −1.74 (1.63) | −1.39 (1.46) | −1.92 (1.94) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | 0.16 (0.63) | 0.23 (0.73) | 0.12 (0.60) | 0.20 (0.72) |

| t-test p-value | 0.299 | 0.194 | 0.435 | 0.296 | |

| WSR p-value | 0.304 | 0.181 | 0.562 | 0.188 | |

| BMI (2 to 4 years old) | n | 11 | 12 | 13 | 12 |

| Baseline z-score | Mean (SD) | −0.08 (1.42) | −0.54 (1.25) | −0.58 (1.03) | −0.55 (1.39) |

| z-score at month | Mean (SD) | −0.56 (1.78) | −0.81 (1.58) | −0.36 (1.41) | −0.11 (1.67) |

| z-score change | Mean (SD) | −0.48 (1.56) | −0.27 (1.66) | 0.22 (1.60) | 0.44 (1.49) |

| t-test p-value | 0.333 | 0.584 | 0.635 | 0.329 | |

| WSR p-value | 0.083 | 0.470 | 0.787 | 0.424 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Freeman, A.J.; Reid, E.; Schindler, T.; Sferra, T.J.; Bice, B.; Deschamp, A.; Thomas, H.; Recker, D.P.; Remmers, A.E. Real-World Evidence of Growth Improvement in Children 1 to 5 Years of Age Receiving Enteral Formula Administered Through an Immobilized Lipase Cartridge. Nutrients 2026, 18, 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020287

Freeman AJ, Reid E, Schindler T, Sferra TJ, Bice B, Deschamp A, Thomas H, Recker DP, Remmers AE. Real-World Evidence of Growth Improvement in Children 1 to 5 Years of Age Receiving Enteral Formula Administered Through an Immobilized Lipase Cartridge. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):287. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020287

Chicago/Turabian StyleFreeman, Alvin Jay, Elizabeth Reid, Terri Schindler, Thomas J. Sferra, Barbara Bice, Ashley Deschamp, Heather Thomas, David P. Recker, and Ann E. Remmers. 2026. "Real-World Evidence of Growth Improvement in Children 1 to 5 Years of Age Receiving Enteral Formula Administered Through an Immobilized Lipase Cartridge" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020287

APA StyleFreeman, A. J., Reid, E., Schindler, T., Sferra, T. J., Bice, B., Deschamp, A., Thomas, H., Recker, D. P., & Remmers, A. E. (2026). Real-World Evidence of Growth Improvement in Children 1 to 5 Years of Age Receiving Enteral Formula Administered Through an Immobilized Lipase Cartridge. Nutrients, 18(2), 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020287