Altered Plasma Endocannabinoids and Oxylipins in Adolescents with Major Depressive Disorders: A Case–Control Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Collection and Pre-Analytics

2.3. Measurement of Oxylipins and Endocannabinoids in Plasma

2.4. Instrumental Setup

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

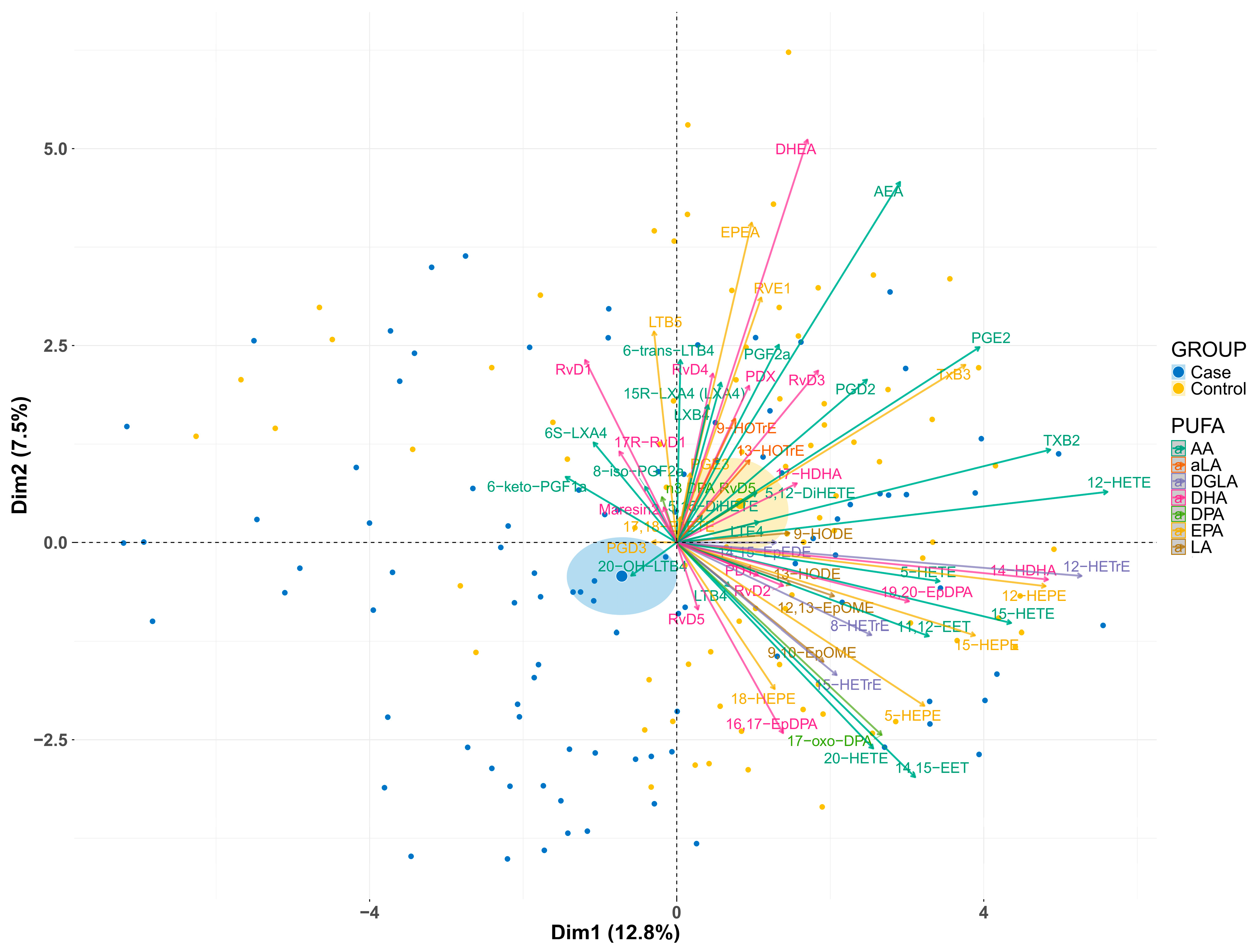

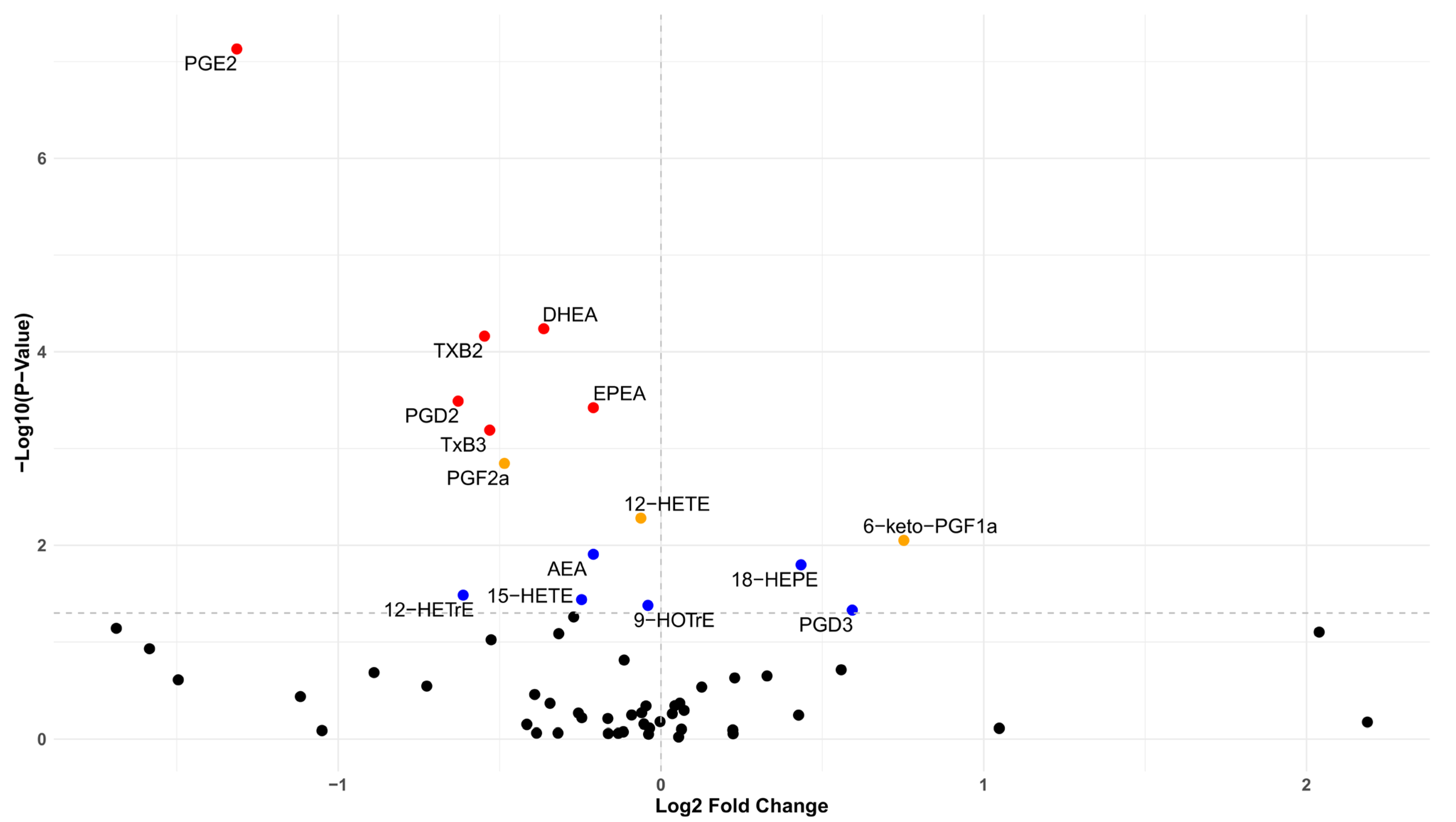

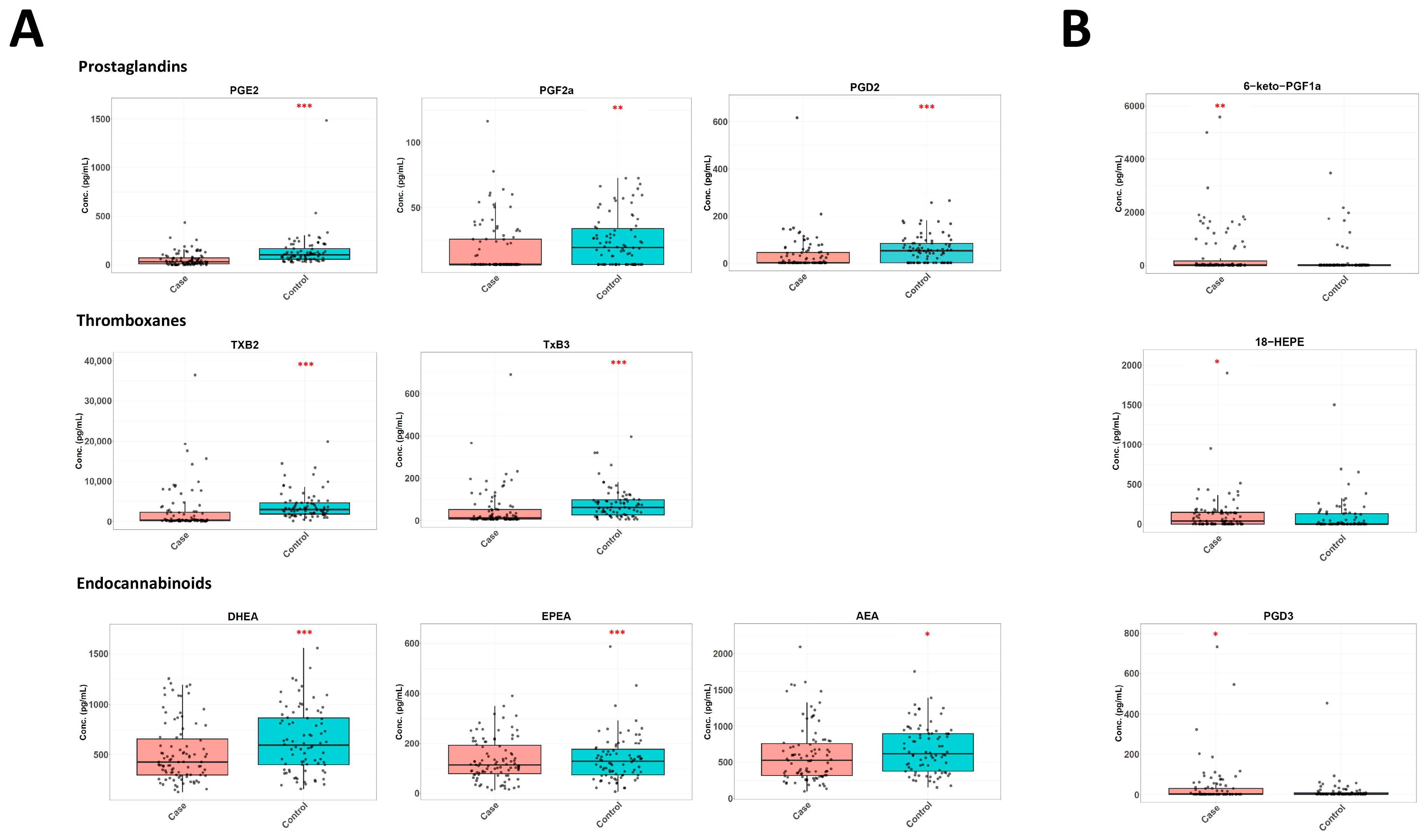

3.1. Differences in the Lipidome Between Cases and Controls

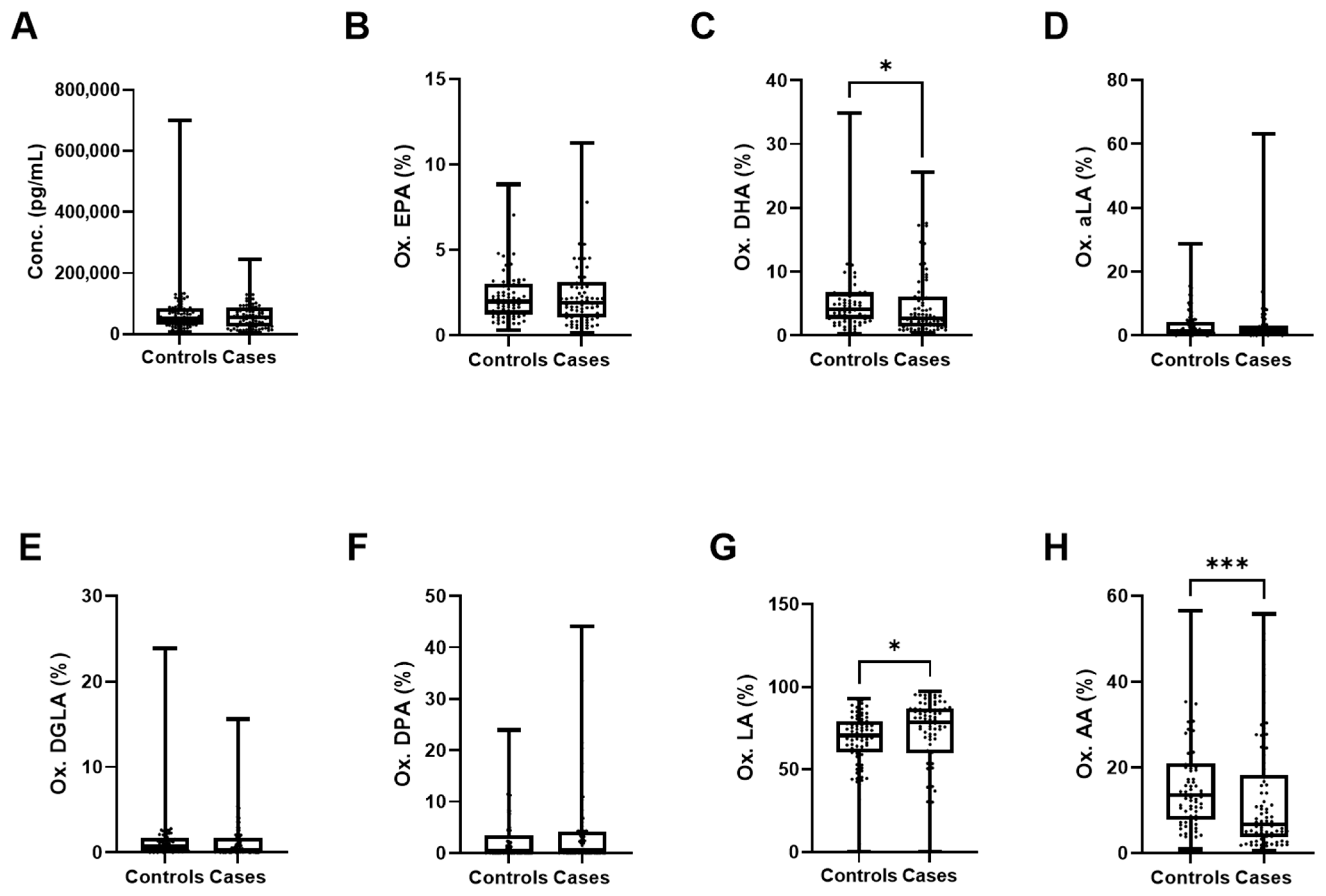

3.2. Contribution of Individual PUFAs to Lipidomic Differences

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PGD2 | Prostaglandin D2 |

| PGF2a | Prostaglandin F2a |

| TXB2 | Thromboxane B2 |

| TxB3 | Thromboxane B3 |

| AEA | Arachidonoyl ethanolamide |

| EPEA | Eicosapentaenoyl ethanolamide |

| DHEA | Docosahexaenoyl ethanolamide |

| PGF1a | Prostaglandin F1a |

| PGD3 | Prostaglandin D3 |

| AA | Arachidonic acid |

| SSRIs | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| LC-PUFAs | Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| PPAR-γ | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor gamma |

| FFAR4 | Free fatty acid receptor 4 |

| GPR120 | G Protein-coupled receptor 120 |

| FAAH | Fatty acid amide hydrolase |

| MAGL | Monoacylglycerol lipase |

| SNSF | Swiss National Science Foundation |

| DSM-IV | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition |

| CDRS-R | Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised |

| K-SADS.PL | Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia |

| M.I.N.I. KID | Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| UHPLC-MS/MS | Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| LLOQ | Lower limit of quantification |

| S/N | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| ALOX5 | Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase |

| DGLA | Dihomo-γ linoleic acid |

| LA | Linoleic acid |

| aLA | α-linolenic acid |

| DPA | Docosapentaenoic acid |

| HOTrE | Hydroxyoctadecatrienoic acid |

| HETrE | Hydroxyeicosatrienoic acid |

| HETE | Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid |

| HEPE | Hydroxyeicosapentaenoic acid |

| CB1 | Cannabinoid receptor 1 |

| CB2 | Cannabinoid receptor 2 |

| TRPV1 | Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 |

| HODE | Hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid |

References

- Bitter, I.; Szekeres, G.; Cai, Q.; Feher, L.; Gimesi-Orszagh, J.; Kunovszki, P.; El Khoury, A.C.; Dome, P.; Rihmer, Z. Mortality in patients with major depressive disorder: A nationwide population-based cohort study with 11-year follow-up. Eur. Psychiatry 2024, 67, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Villavicencio, F.; Yeung, D.; Perin, J.; Lopez, G.; Strong, K.L.; Black, R.E. National, regional, and global causes of mortality in 5–19-year-olds from 2000 to 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e337–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Kuai, M. The global burden of depression in adolescents and young adults, 1990–2021: Systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiniger, C.; Chok, L.; Fernandes, D.; Barrense-Dias, Y. Prevalence and factors associated with depression and anxiety in young people in Switzerland and Liechtenstein in the post pandemic context. Discov. Psychol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazell, P. Depression in children. BMJ 2002, 325, 229–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, A.; Zhou, X.; Del Giovane, C.; Hetrick, S.E.; Qin, B.; Whittington, C.; Coghill, D.; Zhang, Y.; Hazell, P.; Leucht, S.; et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: A network meta-analysis. Lancet 2016, 388, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkman, H.O.; Hersberger, M.; Walitza, S.; Berger, G.E. Disentangling the Molecular Mechanisms of the Antidepressant Activity of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campisi, S.C.; Zasowski, C.; Bradley-Ridout, G.; Schumacher, A.; Szatmari, P.; Korczak, D. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for depression in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 11, CD014803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, R.K.; Jandacek, R.; Tso, P.; Dwivedi, Y.; Ren, X.; Pandey, G.N. Lower docosahexaenoic acid concentrations in the postmortem prefrontal cortex of adult depressed suicide victims compared with controls without cardiovascular disease. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 1187–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Zhang, M.-Q.; Xue, Y.; Yang, R.; Tang, M.-M. Dietary of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids influence neurotransmitter systems of rats exposed to unpredictable chronic mild stress. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 376, 112172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norouziasl, R.; Zeraattalab-Motlagh, S.; Jayedi, A.; Shab-Bidar, S. Efficacy and safety of n-3 fatty acids supplementation on depression: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 131, 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabbay, V.; Freed, R.D.; Alonso, C.M.; Senger, S.; Stadterman, J.; Davison, B.A.; Klein, R.G. A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial of Omega-3 Fatty Acids as a Monotherapy for Adolescent Depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2018, 79, 13285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troubat, R.; Barone, P.; Leman, S.; Desmidt, T.; Cressant, A.; Atanasova, B.; Brizard, B.; El Hage, W.; Surget, A.; Belzung, C.; et al. Neuroinflammation and depression: A review. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2021, 53, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppedisano, F.; Macrì, R.; Gliozzi, M.; Musolino, V.; Carresi, C.; Maiuolo, J.; Bosco, F.; Nucera, S.; Zito, M.C.; Guarnieri, L.; et al. The Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of n-3 PUFAs: Their Role in Cardiovascular Protection. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wawrzyniak, P.; Noureddine, N.; Wawrzyniak, M.; Lucchinetti, E.; Krämer, S.D.; Rogler, G.; Zaugg, M.; Hersberger, M. Nutritional Lipids and Mucosal Inflammation. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 65, e1901269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.-E.; Koh, J.-M.; Im, D.-S. Free fatty acid receptor 4 (FFA4) activation attenuates obese asthma by suppressing adiposity and resolving metaflammation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, M.; Luo, W.; Sui, Y.; Li, Z.; Hua, J. Dietary n-3 PUFA Protects Mice from Con A Induced Liver Injury by Modulating Regulatory T Cells and PPAR-γ Expression. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerab, D.; Blangero, F.; da Costa, P.C.T.; Alves, J.L.d.B.; Kefi, R.; Jamoussi, H.; Morio, B.; Eljaafari, A. Beneficial Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Obesity and Related Metabolic and Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.Y.; Talukdar, S.; Bae, E.J.; Imamura, T.; Morinaga, H.; Fan, W.Q.; Li, P.; Lu, W.J.; Watkins, S.M.; Olefsky, J.M. GPR120 is an omega-3 fatty acid receptor mediating potent anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects. Cell 2010, 142, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbs, M.; Leng, S.; Devassy, J.G.; Monirujjaman, M.; Aukema, H.M. Advances in Our Understanding of Oxylipins Derived from Dietary PUFAs. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, M.C.; Levy, B.D. Specialized pro-resolving mediators: Endogenous regulators of infection and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peh, H.Y.; Chen, J. Pro-resolving lipid mediators and therapeutic innovations in resolution of inflammation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 265, 108753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyall, S.C. Interplay Between n-3 and n-6 Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and the Endocannabinoid System in Brain Protection and Repair. Lipids 2017, 52, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.; Mayans, J.; Guarro, M.; Canosa, I.; Mestre-Pintó, J.; Fonseca, F.; Torrens, M. Peripheral endocannabinoids in major depressive disorder and alcohol use disorder: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbi, A.; Madras, B.K.; George, S.R. Endocannabinoid System and Exogenous Cannabinoids in Depression and Anxiety: A Review. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, M.; Skrzydlewska, E. Metabolism of endocannabinoids. Postepy Hig. I Med. Dosw. 2016, 70, 830–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-J.; Chen, W.-W.; Zhang, X. Endocannabinoid system: Role in depression, reward and pain control (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 2899–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osafo, N.; Yeboah, O.K.; Antwi, A.O. Endocannabinoid system and its modulation of brain, gut, joint and skin inflammation. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 3665–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osuna, E.; Herter-Aeberli, I.; Probst, S.; Emery, S.; Albermann, M.; Baumgartner, N.; Strumberger, M.; Ricci, C.; Schmeck, K.; Walitza, S.; et al. Associations of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid status and intake with paediatric major depressive disorder in Swiss adolescents: A case-control study. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 339, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häberling, I.; Berger, G.; Schmeck, K.; Held, U.; Walitza, S. Omega-3 Fatty Acids as a Treatment for Pediatric Depression. A Phase III, 36 Weeks, Multi-Center, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Randomized Superiority Study. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartling, I.; Cremonesi, A.; Osuna, E.; Lou, P.-H.; Lucchinetti, E.; Zaugg, M.; Hersberger, M. Quantitative profiling of inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators in human adolescents and mouse plasma using UHPLC-MS/MS. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2021, 59, 1811–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schebb, N.H.; Kampschulte, N.; Hagn, G.; Plitzko, K.; Meckelmann, S.W.; Ghosh, S.; Joshi, R.; Kuligowski, J.; Vuckovic, D.; Botana, M.T.; et al. Technical recommendations for analyzing oxylipins by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Sci. Signal. 2025, 18, eadw1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyama, T.; Sasaki, S.; Okada-Iwabu, M.; Murakami, M. Recent Progress in N-Acylethanolamine Research: Biological Functions and Metabolism Regulated by Two Distinct N-Acyltransferases: cPLA2ε and PLAAT Enzymes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, A.; Eggenberger, L.; Debelak, R.; Kirschbaum, C.; Häberling, I.; Osuna, E.; Strumberger, M.; Walitza, S.; Baumgartner, J.; Herter-Aeberli, I.; et al. Major depressive disorder in children and adolescents is associated with reduced hair cortisol and anandamide (AEA): Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from a large randomized clinical trial. Transl. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M.N.; Miller, G.E.; Carrier, E.J.; Gorzalka, B.B.; Hillard, C.J. Circulating endocannabinoids and N-acyl ethanolamines are differentially regulated in major depression and following exposure to social stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 1257–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnke, A.; Gumpp, A.M.; Rojas, R.; Sänger, T.; Lutz-Bonengel, S.; Moser, D.; Schelling, G.; Krumbholz, A.; Kolassa, I.-T. Circulating inflammatory markers, cell-free mitochondrial DNA, cortisol, endocannabinoids, and N-acylethanolamines in female depressed outpatients. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 24, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Sanchiz, P.; Nogueira-Arjona, R.; Pastor, A.; Araos, P.; Serrano, A.; Boronat, A.; Garcia-Marchena, N.; Mayoral, F.; Bordallo, A.; Alen, F.; et al. Plasma concentrations of oleoylethanolamide in a primary care sample of depressed patients are increased in those treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-type antidepressants. Neuropharmacology 2019, 149, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccaro, E.F.; Hill, M.N.; Robinson, L.; Lee, R.J. Circulating endocannabinoids and affect regulation in human subjects. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 92, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.N.; Miller, G.E.; Ho, W.S.; Gorzalka, B.B.; Hillard, C.J. Serum endocannabinoid content is altered in females with depressive disorders: A preliminary report. Pharmacopsychiatry 2008, 41, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersani, G.; Pacitti, F.; Iannitelli, A.; Caroti, E.; Quartini, A.; Xenos, D.; Marconi, M.; Cuoco, V.; Bigio, B.; Bowles, N.P.; et al. Inverse correlation between plasma 2-arachidonoylglycerol levels and subjective severity of depression. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 2021, 36, e2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Lin, L.; Bazinet, R.P.; Chien, Y.-C.; Chang, J.P.-C.; Satyanarayanan, S.K.; Su, H.; Su, K.-P. Clinical Efficacy and Biological Regulations of ω–3 PUFA-Derived Endocannabinoids in Major Depressive Disorder. Psychother. Psychosom. 2019, 88, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarazúa-Guzmán, S.; Vicente-Martínez, J.G.; Pinos-Rodríguez, J.M.; Arevalo-Villalobos, J.I. An overview of major depression disorder: The endocannabinoid system as a potential target for therapy. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2024, 135, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitsillou, E.; Bresnehan, S.M.; Kagarakis, E.A.; Wijoyo, S.J.; Liang, J.; Hung, A.; Karagiannis, T.C. The cellular and molecular basis of major depressive disorder: Towards a unified model for understanding clinical depression. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 753–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarrone, M.; Di Marzo, V.; Gertsch, J.; Grether, U.; Howlett, A.C.; Hua, T.; Makriyannis, A.; Piomelli, D.; Ueda, N.; van der Stelt, M. Goods and Bads of the Endocannabinoid System as a Therapeutic Target: Lessons Learned after 30 Years. Pharmacol. Rev. 2023, 75, 885–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharthi, N.; Christensen, P.; Hourani, W.; Ortori, C.; Barrett, D.A.; Bennett, A.J.; Chapman, V.; Alexander, S.P. n−3 polyunsaturated N-acylethanolamines are CB2 cannabinoid receptor-preferring endocannabinoids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2018, 1863, 1433–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, I.; Padula, L.P.; Semeraro, F.; Marrangone, C.; Inserra, A.; De Risio, L.; Boffa, M.; Zoratto, F.; Borgi, M.; Guidotti, R.; et al. Endocannabinoids, depression, and treatment resistance: Perspectives on effective therapeutic interventions. Psychiatry Res. 2025, 352, 116697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Aguirre, C.; Cinar, R.; Rocha, L. Targeting Endocannabinoid System in Epilepsy: For Good or for Bad. Neuroscience 2022, 482, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuna, E.; Baumgartner, J.; Wunderlin, O.; Emery, S.; Albermann, M.; Baumgartner, N.; Schmeck, K.; Walitza, S.; Strumberger, M.; Hersberger, M.; et al. Iron status in Swiss adolescents with paediatric major depressive disorder and healthy controls: A matched case–control study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.T.; Williams, J.S.; Pandarinathan, L.; Courville, A.; Keplinger, M.R.; Janero, D.R.; Vouros, P.; Makriyannis, A.; Lammi-Keefe, C.J. Comprehensive profiling of the human circulating endocannabinoid metabolome: Clinical sampling and sample storage parameters. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. CCLM 2008, 46, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, M.; Bindila, L.; Graessler, J.; Shevchenko, A. Quantitative profiling of endocannabinoids in lipoproteins by LC–MS/MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 5125–5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bus, I.; Witkamp, R.; Zuilhof, H.; Albada, B.; Balvers, M. The role of n-3 PUFA-derived fatty acid derivatives and their oxygenated metabolites in the modulation of inflammation. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2019, 144, 106351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougle, D.R.; Watson, J.E.; Abdeen, A.A.; Adili, R.; Caputo, M.P.; Krapf, J.E.; Johnson, R.W.; Kilian, K.A.; Holinstat, M.; Das, A. Anti-inflammatory ω-3 endocannabinoid epoxides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E6034–E6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, N.T.; Walker, V.J.; Hollenberg, P.F. Oxidation of the endogenous cannabinoid arachidonoyl ethanolamide by the cytochrome p450 monooxygenases: Physiological and pharmacological implications. Pharmacol. Rev. 2010, 62, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jing, M.; Mohamed, N.; Rey-Dubois, C.; Zhao, S.; Aukema, H.M.; House, J.D. The Effect of Increasing Concentrations of Omega-3 Fatty Acids from either Flaxseed Oil or Preformed Docosahexaenoic Acid on Fatty Acid Composition, Plasma Oxylipin, and Immune Response of Laying Hens. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 2105–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzner, L.; Esselun, C.; Franke, N.; Schoenfeld, K.; Eckert, G.P.; Schebb, N.H. Effect of dietary EPA and DHA on murine blood and liver fatty acid profile and liver oxylipin pattern depending on high and low dietary n6-PUFA. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 9177–9191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchardt, J.P.; Schmidt, S.; Kressel, G.; Willenberg, I.; Hammock, B.D.; Hahn, A.; Schebb, N.H. Modulation of blood oxylipin levels by long-chain omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in hyper- and normolipidemic men. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2014, 90, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchardt, J.P.; Ostermann, A.I.; Stork, L.; Fritzsch, S.; Kohrs, H.; Greupner, T.; Hahn, A.; Schebb, N.H. Effect of DHA supplementation on oxylipin levels in plasma and immune cell stimulated blood. Prostaglandin, Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2017, 121, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vangaveti, V.; Baune, B.T.; Kennedy, R.L. Hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids: Novel regulators of macrophage differentiation and atherogenesis. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 1, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadiiska, M.; Erve, T.V.; Mason, R.; Ferguson, K. The exposure-dependent increases in 8-iso-PGF2α and the significance of decoding its sources to identify a specific indicator of oxidative stress or inflammation. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 128, S117–S118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieb, J.; Karmali, R.; Horrobin, D. Elevated levels of prostaglandin e2 and thromboxane B2 in depression. Prostaglandins Leukot. Med. 1983, 10, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohishi, K.; Ueno, R.; Nishino, S.; Sakai, T.; Hayaishi, O. Increased level of salivary prostaglandins in patients with major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 1988, 23, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.; Wei, H.; Zhu, W.; Shen, Y.; Xu, Q. Decreased Prostaglandin D2 Levels in Major Depressive Disorder Are Associated with Depression-Like Behaviors. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 20, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thon, J.N.; Schubert, P.; Devine, D.V. Platelet Storage Lesion: A New Understanding from a Proteomic Perspective. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2008, 22, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chakravarty, A.; Sreetharan, A.; Osuna, E.; Herter-Aeberli, I.; Häberling, I.; Baumgartner, J.; Berger, G.E.; Hersberger, M. Altered Plasma Endocannabinoids and Oxylipins in Adolescents with Major Depressive Disorders: A Case–Control Study. Nutrients 2026, 18, 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020280

Chakravarty A, Sreetharan A, Osuna E, Herter-Aeberli I, Häberling I, Baumgartner J, Berger GE, Hersberger M. Altered Plasma Endocannabinoids and Oxylipins in Adolescents with Major Depressive Disorders: A Case–Control Study. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):280. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020280

Chicago/Turabian StyleChakravarty, Akash, Abinaya Sreetharan, Ester Osuna, Isabelle Herter-Aeberli, Isabelle Häberling, Jeannine Baumgartner, Gregor E. Berger, and Martin Hersberger. 2026. "Altered Plasma Endocannabinoids and Oxylipins in Adolescents with Major Depressive Disorders: A Case–Control Study" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020280

APA StyleChakravarty, A., Sreetharan, A., Osuna, E., Herter-Aeberli, I., Häberling, I., Baumgartner, J., Berger, G. E., & Hersberger, M. (2026). Altered Plasma Endocannabinoids and Oxylipins in Adolescents with Major Depressive Disorders: A Case–Control Study. Nutrients, 18(2), 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020280