Algae and Algal Protein in Human Nutrition: A Narrative Review of Health Outcomes from Clinical Studies

Abstract

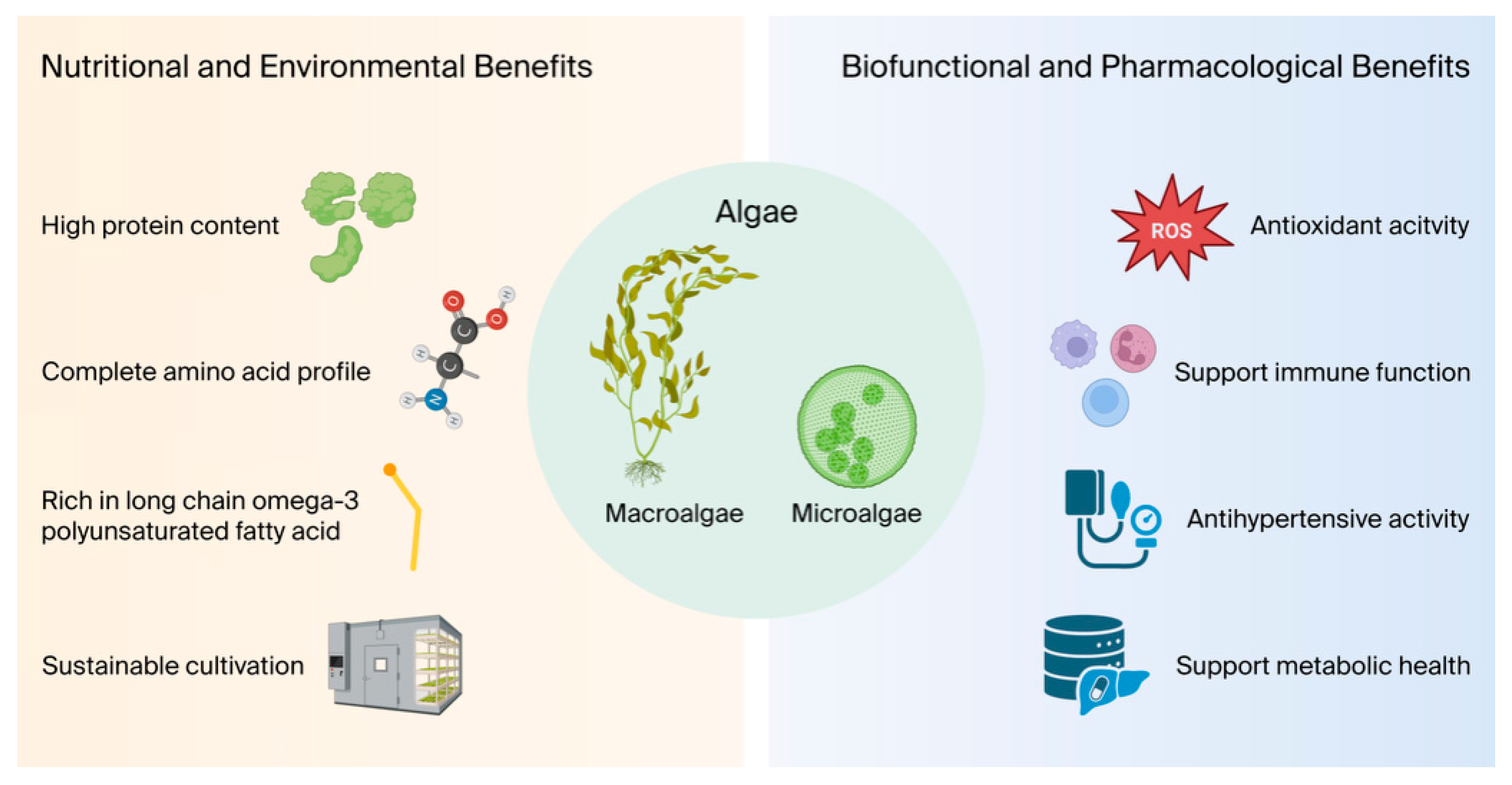

1. Introduction

2. Nutritional Values

3. Protein Quality and Health Effects of Algal Proteins

4. Cardiovascular Health and Lipoprotein Metabolism

5. Weight Management and Metabolic Health

| Algae | Preparation | Participants | Dose | Duration | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gelidium elegans | Extract tablets | Overweight/obese adults | 1000 mg/d | 12 weeks | Decrease in body weight, BMI, fat mass and visceral fat. | [40] |

| Phyaeodactylum tricornutum | Extract capsule | Sedentary overweight women | 220 mg/d | 12 weeks | Preservation of bone mass and increased bone density; improvements in cardio-metabolic and quality of life markers. | [41] |

| Undaria pinnatifida | Extract capsule | Obese, non-diabetic premenopausal women | 2400 mg/d | 16 weeks | Significant weight loss, body fat reduction, marked liver fat reduction, decreased blood pressure. | [42] |

| Laminaria japonica | Whole biomass tablet | Overweight adults | 6000 mg/d | 8 weeks | Body weight percentage in men, no change in women, decrease LDL-C in non-hyperlipidemic individuals. | [43] |

| Laminaria hyperborean/Lessonia trabeculata | Extract | Healthy adults | 9900 mg/d (low)/15,000 mg/d (high) | Acute single day | Enhance short term satiety, reduce glycemic response in high dose. | [45] |

| Porphyridium purpureum | Extract capsule | Overweight/obese adults | 900 mg/d | 8 weeks | Reduced body fat mass, body fat percentage, BMI and visceral fat; decrease in LDL-C, leptin, increase in adiponectin | [46] |

| Pyropia yezoensis | Whole biomass drink | Healthy, young men | 1500 mg/d | 5 days | Increased time to exhaustion, lower post-exercise lactate and ammonia, decrease MDA, increase SOD and GPx. | [47] |

| Ascophyllum nodosum/Fucus vesiculosus | Whole biomass capsule | Healthy adults | 500 mg | Acute single dose | Decrease in plasma insulin, increase in Cederholm insulin sensitivity index | [48] |

| Fucus vesiculosis/Ascophyllum nodosum | Extract capsule | Overweight/obese adults | 712.5 mg/d (F.v.) + 37.5 mg/d (A.n.) | 6 months | Decrease in fasting glucose, fasting insulin, improvement in HOMA-IR, decrease in waist circumference. | [49] |

| Fucus vesiculosis/Ascophyllum nodosum | Extract tablet | Dysglycemia Caucasian | NR | 6 months | Reduction in HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose, postprandial plasma glucose and HOMA-IR, decrease in hs-CRP, TNF-α. | [50] |

| Fucus vesiculosis | Extract capsule | Healthy adults | 500 mg (low)/2000 mg (high) | Acute, 30 min before meal | No significant changes. | [51] |

| Ecklonia cava | Extract tablet | Pre-diabetic adults | 1500 mg/d | 12 weeks | Decrease in postprandial glucose; within treatment: decrease in insulin and C-peptide | [52] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Whole biomass capsule | T2DM patients | 1500 mg/d | 8 weeks | No significant changes. | [53] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Whole biomass capsule | Young women with primary dysmenorrhea | 1500 mg/d | 8 weeks | Decrease in PGE2, PGF2α, hs-CRP, MDA, pain severity, pain duration and systemic symptoms. | [54] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Whole biomass tablet | Obese adults | 1200 mg/d | 8 weeks | Decrease in ALT, AST, improved fasting serum glucose, insulin, HOMA, decrease in hs-CRP. | [55] |

6. Immune Functions

7. Antioxidative Activities

8. Cognitive Functions and Depression

9. Sustainability Potential of Microalgae in Human Nutrition

10. Consumer Acceptance

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, S.; Hayes, M. Algal Proteins: Extraction, Application, and Challenges Concerning Production. Foods 2017, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, I.; Gouveia, L.; Batista, A.; Raymundo, A. Microalgae in Novel Food Products. In Food Chemistry Research Developments; Konstantinos, N., Papadopoulus, P.P., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 75–112. [Google Scholar]

- Puertas, G.; Vázquez, M. Evaluation of the Composition and Functional Properties of Whole Egg Plasma Obtained by Centrifugation. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 5268–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdt, S.L.; Kraan, S. Bioactive Compounds in Seaweed: Functional Food Applications and Legislation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011, 23, 543–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angell, A.R.; Mata, L.; De Nys, R.; Paul, N.A. The Protein Content of Seaweeds: A Universal Nitrogen-to-Protein Conversion Factor of Five. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Á.; Toro-Román, V.; Siquier-Coll, J.; Bartolomé, I.; Muñoz, D.; Maynar-Mariño, M. Effects of Tetraselmis Chuii Microalgae Supplementation on Anthropometric, Hormonal and Hematological Parameters in Healthy Young Men: A Double-Blind Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiefvatter, L.; Frick, K.; Lehnert, K.; Vetter, W.; Montoya-Arroyo, A.; Frank, J.; Schmid-Staiger, U.; Bischoff, S.C. Potentially Beneficial Effects on Healthy Aging by Supplementation of the EPA-Rich Microalgae Phaeodactylum tricornutum or Its Supernatant—A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial in Elderly Individuals. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, L.A.; Meyer, B.J.; Fitton, J.H.; Winberg, P. Improved Plasma Lipids, Anti-Inflammatory Activity, and Microbiome Shifts in Overweight Participants: Two Clinical Studies on Oral Supplementation with Algal Sulfated Polysaccharide. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teas, J.; Braverman, L.E.; Kurzer, M.S.; Pino, S.; Hurley, T.G.; Hebert, J.R. Seaweed and Soy: Companion Foods in Asian Cuisine and Their Effects on Thyroid Function in American Women. J. Med. Food 2007, 10, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquaron, R.; Delange, F.; Marchal, P.; Lognoné, V.; Ninane, L. Bioavailability of Seaweed Iodine in Human Beings. Cell. Mol. Biol. Noisy Gd. Fr. 2002, 48, 563–569. [Google Scholar]

- Noahsen, P.; Kleist, I.; Larsen, H.M.; Andersen, S. Intake of Seaweed as Part of a Single Sushi Meal, Iodine Excretion and Thyroid Function in Euthyroid Subjects: A Randomized Dinner Study. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2020, 43, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.D.; Bassett, B.; Burge, M.R. Effects of Kelp Supplementation on Thyroid Function in Euthyroid Subjects. Endocr. Pract. 2003, 9, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, J.; Zare, F.; Pletch, A. Pulse Proteins: Processing, Characterization, Functional Properties and Applications in Food and Feed. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporgno, M.P.; Mathys, A. Trends in Microalgae Incorporation into Innovative Food Products with Potential Health Benefits. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.W. Micro-Algae as a Source of Protein. Biotechnol. Adv. 2007, 25, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tibbetts, S.; Patelakis, S. Apparent Digestibility Coefficients (ADCs) of Intact-Cell Marine Microalgae Meal (Pavlova sp. 459) for Juvenile Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar L.). Aquaculture 2021, 546, 737236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, Q.; Yue, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, N.; Geng, L.; Zhang, Q. Isolation, Identification and in Vivo Antihypertensive Effect of Novel Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitory Peptides from Spirulina Protein Hydrolysate. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 9108–9118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahraki Jazinaki, M.; Rashidmayvan, M.; Rahbarinejad, P.; Shadmand Foumani Moghadam, M.R.; Pahlavani, N. Effects of Spirulina Supplementation on C-Reactive Protein (CRP): A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, I.; West, S.; Monteyne, A.J.; Finnigan, T.J.A.; Abdelrahman, D.R.; Murton, A.J.; Stephens, F.B.; Wall, B.T. Algae Ingestion Increases Resting and Exercised Myofibrillar Protein Synthesis Rates to a Similar Extent as Mycoprotein in Young Adults. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 3406–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Mantia, I.; Maniaci, A.; Scibilia, G.; Scollo, P. Effects of a Dietary Microalgae (Arthrospira platensis) Supplement on Stress, Well-Being, and Performance in Water Polo Players: A Clinical Case Series. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, V.; Siquier-Coll, J.; Bartolomé, I.; Robles-Gil, M.C.; Rodrigo, J.; Maynar-Mariño, M. Effects of Tetraselmis Chuii Microalgae Supplementation on Ergospirometric, Haematological and Biochemical Parameters in Amateur Soccer Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, R.E.; Carmack, C.A.; Wise, C.M. Nutritional Supplementation with Chlorella pyrenoidosa for Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Pilot Study. Phytother. Res. 2000, 14, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, S.A.; Smith, B.; Nolan, C.; Shay, J.; Kralovec, J. Safety and Immunoenhancing Effect of a Chlorella-Derived Dietary Supplement in Healthy Adults Undergoing Influenza Vaccination: Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2003, 169, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Nishimura, C.; Kan, H.; Kanno, T.; Nakamura, T.; Matsubayashi, T. Anti-Hypertensive Effect of γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA)-Rich Chlorella on High-Normal Blood Pressure and Borderline Hypertension in Placebo-Controlled Double Blind Study. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2009, 31, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.; Dordevic, A.L.; Cox, K.; Scholey, A.; Ryan, L.; Bonham, M.P. Twelve Weeks’ Treatment with a Polyphenol-Rich Seaweed Extract Increased HDL Cholesterol with No Change in Other Biomarkers of Chronic Disease Risk in Overweight Adults: A Placebo-Controlled Randomized Trial. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2021, 96, 108777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Briskey, D.; Nalley, J.O.; Ganuza, E. Omega-3 Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA) Rich Extract from the Microalga Nannochloropsis Decreases Cholesterol in Healthy Individuals: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Three-Month Supplementation Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, K.C.; Yurko-Mauro, K.; Dicklin, M.R.; Schild, A.L.; Geohas, J.G. A New, Microalgal DHA- and EPA-Containing Oil Lowers Triacylglycerols in Adults with Mild-to-Moderate Hypertriglyceridemia. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2014, 91, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Maldonado, E.; Alcorta, A.; Zapatera, B.; Vaquero, M.P. Changes in Fatty Acid Levels after Consumption of a Novel Docosahexaenoic Supplement from Algae: A Crossover Randomized Controlled Trial in Omnivorous, Lacto-Ovo Vegetarians and Vegans. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 1691–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geppert, J.; Kraft, V.; Demmelmair, H.; Koletzko, B. Docosahexaenoic Acid Supplementation in Vegetarians Effectively Increases Omega-3 Index: A Randomized Trial. Lipids 2005, 40, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiefvatter, L.; Lehnert, K.; Frick, K.; Montoya-Arroyo, A.; Frank, J.; Vetter, W.; Schmid-Staiger, U.; Bischoff, S.C. Oral Bioavailability of Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Carotenoids from the Microalgae Phaeodactylum tricornutum in Healthy Young Adults. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandgruber, F.; Höger, A.-L.; Kunze, J.; Schenz, B.; Griehl, C.; Kiehntopf, M.; Kipp, K.; Kühn, J.; Stangl, G.I.; Lorkowski, S.; et al. Impact of Regular Intake of Microalgae on Nutrient Supply and Cardiovascular Risk Factors: Results from the NovAL Intervention Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geppert, J.; Kraft, V.; Demmelmair, H.; Koletzko, B. Microalgal Docosahexaenoic Acid Decreases Plasma Triacylglycerol in Normolipidaemic Vegetarians: A Randomised Trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 95, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, N.H.; Lim, Y.; Park, J.E.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kwon, S.W.; Kwon, O. Impact of Daily Chlorella Consumption on Serum Lipid and Carotenoid Profiles in Mildly Hypercholesterolemic Adults: A Double-Blinded, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Lim, Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kwon, O. A Dietary Cholesterol Challenge Study to Assess Chlorella Supplementation in Maintaining Healthy Lipid Levels in Adults: A Double-Blinded, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Leite, M.; Martins, D.; Ferreira, A.C.; Silva, C.; Trindade, F.; Saraiva, F.; Vitorino, R.; Barros, R.; Lima, P.A.; Leite-Moreira, A.; et al. The Role of Chlorella and Spirulina as Adjuvants of Cardiovascular Risk Factor Control: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2025, 17, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, K.; Tsuji, M.; Nakamura, K.; Oba, S.; Nishizawa, S.; Yamamoto, K.; Watanabe, K.; Ando, K.; Nagata, C. Effect of Dietary Nori (Dried Laver) on Blood Pressure in Young Japanese Children: An Intervention Study. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 31, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hata, Y.; Nakajima, K.; Uchida, J.; Hidaka, H.; Nakano, T. Clinical Effects of Brown Seaweed, Undaria pinnatifida (Wakame), on Blood Pressure in Hypertensive Subjects. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2001, 30, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, S.; Fryar, C.; Stierman, B.; Ogden, C. Obesity and Severe Obesity Prevalence in Adults: United States, August 2021–August 2023; National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.): Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.O.; Kim, Y.N.; Lee, D.-C. Effects of Gelidium Elegans on Weight and Fat Mass Reduction and Obesity Biomarkers in Overweight or Obese Adults: A Randomized Double-Blinded Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, B.; Maury, J.; Jenkins, V.; Nottingham, K.; Xing, D.; Gonzalez, D.E.; Leonard, M.; Kendra, J.; Ko, J.; Yoo, C.; et al. Effects of Supplementation with Microalgae Extract from Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Mi136) to Support Benefits from a Weight Management Intervention in Overweight Women. Nutrients 2024, 16, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidov, M.; Ramazanov, Z.; Seifulla, R.; Grachev, S. The Effects of XanthigenTM in the Weight Management of Obese Premenopausal Women with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Normal Liver Fat. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2010, 12, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoe, S.; Yamanaka, C.; Ohtoshi, H.; Nakamura, F.; Fujiwara, S. Effects of Daily Kelp (Laminaria japonica) Intake on Body Composition, Serum Lipid Levels, and Thyroid Hormone Levels in Healthy Japanese Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind Study. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhu, D.; Chen, F.; Chen, J.; Ji, X.; Hou, K. The Global, Regional and National Burden of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the Past, Present and Future: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1192629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georg, M.G.; Kristensen, M.; Belza, A.; Knudsen, J.C.; Astrup, A. Acute Effect of Alginate-Based Preload on Satiety Feelings, Energy Intake, and Gastric Emptying Rate in Healthy Subjects. Obesity 2012, 20, 1851–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, K.A.M.; Meijer, S.; Roeters van Lennep, J.E.; Wang, X.; Özcan, B.; Voortman, G.; Liu, H.; Castro Cabezas, M.; Berk, K.A.; Mulder, M.T. The Effect of Sargassum Fusiforme and Fucus vesiculosus on Continuous Glucose Levels in Overweight Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Feasibility Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodouhè, M.; Marois, J.; Guay, V.; Leblanc, N.; Weisnagel, S.J.; Bilodeau, J.-F.; Jacques, H. Marginal Impact of Brown Seaweed Ascophyllum Nodosum and Fucus vesiculosus Extract on Metabolic and Inflammatory Response in Overweight and Obese Prediabetic Subjects. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, M.-E.; Couture, P.; Lamarche, B. A Randomised Crossover Placebo-Controlled Trial Investigating the Effect of Brown Seaweed (Ascophyllum nodosum and Fucus vesiculosus) on Postchallenge Plasma Glucose and Insulin Levels in Men and Women. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 36, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martin, S.; Gabbia, D.; Carrara, M.; Ferri, N. The Brown Algae Fucus vesiculosus and Ascophyllum nodosum Reduce Metabolic Syndrome Risk Factors: A Clinical Study. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13, 1691–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, G.; Cicero, A.F.G.; D’Angelo, A.; Maffioli, P. Ascophyllum nodosum and Fucus vesiculosus on Glycemic Status and on Endothelial Damage Markers in Dysglicemic Patients. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.; Dordevic, A.L.; Ryan, L.; Bonham, M.P. The Impact of a Single Dose of a Polyphenol-Rich Seaweed Extract on Postprandial Glycaemic Control in Healthy Adults: A Randomised Cross-Over Trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-H.; Jeon, Y.-J. Efficacy and Safety of a Dieckol-Rich Extract (AG-Dieckol) of Brown Algae, Ecklonia Cava, in Pre-Diabetic Individuals: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, A.M.; Keshavarz, S.A.; Nasli-Esfahani, E.; Amiri, F.; Janani, L. The Effects of Chlorella Supplementation on Glycemic Control, Lipid Profile and Anthropometric Measures on Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 3131–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidari, F.; Homayouni, F.; Helli, B.; Haghighizadeh, M.H.; Farahmandpour, F. Effect of Chlorella Supplementation on Systematic Symptoms and Serum Levels of Prostaglandins, Inflammatory and Oxidative Markers in Women with Primary Dysmenorrhea. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 229, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimi-Mameghani, M.; Sadeghi, Z.; Farhangi, M.A.; Vaghef-Mehrabany, E.; Aliashrafi, S. Glucose Homeostasis, Insulin Resistance and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Beneficial Effects of Supplementation with Microalgae Chlorella Vulgaris: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, M.; Karimi, M.; Akhgarjand, C.; Ghotboddin Mohammadi, S.; Pam, P.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Pirzad, S.; Amirkhan-Dehkordi, M.; Shahrbaf, M.A.; Henselmans, M.; et al. Effects of Spirulina Supplementation on Body Composition in Adults: A GRADE-Assessed and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis of RCTs. Nutr. Metab. 2025, 22, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, S.; Takekoshi, H.; Nakano, M. Chlorella (Chlorella pyrenoidosa) Supplementation Decreases Dioxin and Increases Immunoglobulin A Concentrations in Breast Milk. J. Med. Food 2007, 10, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidley, C.; Davison, G. The Effect of Chlorella pyrenoidosa Supplementation on Immune Responses to 2 Days of Intensified Training. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 2529–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuki, T.; Shimizu, K.; Iemitsu, M.; Kono, I. Chlorella Intake Attenuates Reduced Salivary SIgA Secretion in Kendotraining Camp Participants. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuki, T.; Shimizu, K.; Iemitsu, M.; Kono, I. Salivary Secretory Immunoglobulin a Secretion Increases after 4-Weeks Ingestion of Chlorella-Derived Multicomponent Supplement in Humans: A Randomized Cross over Study. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negishi, H.; Mori, M.; Mori, H.; Yamori, Y. Supplementation of Elderly Japanese Men and Women with Fucoidan from Seaweed Increases Immune Responses to Seasonal Influenza Vaccination. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 1794–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.H.; Baek, S.H.; Woo, Y.; Han, J.K.; Kim, B.G.; Kim, O.Y.; Lee, J.H. Beneficial Immunostimulatory Effect of Short-Term Chlorella Supplementation: Enhancement of Natural Killercell Activity and Early Inflammatory Response (Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial). Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azocar, J.; Diaz, A. Efficacy and Safety of Chlorella Supplementation in Adults with Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.-J.; Jang, H.-Y.; Jung, E.-S.; Noh, S.-O.; Shin, S.-W.; Ha, K.-C.; Baek, H.-I.; Ahn, B.-J.; Oh, T.-H.; Chae, S.-W. Effects of Porphyra Tenera Supplementation on the Immune System: A Randomized, Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.; Dragar, C.; Elliot, K.; Fitton, J.; Godwin, J.; Thompson, K. GFS, a Preparation of Tasmanian Undaria pinnatifida Is Associated with Healing and Inhibition of Reactivation of Herpes. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2002, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, T.; Eickhoff, P.; Pruckner, N.; Vollnhofer, G.; Fischmeister, G.; Diakos, C.; Rauch, M.; Verdianz, M.; Zoubek, A.; Gadner, H.; et al. Lessons Learned from a Double-Blind Randomised Placebo-Controlled Study with a Iota-Carrageenan Nasal Spray as Medical Device in Children with Acute Symptoms of Common Cold. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, N.; Takahashi, K.; Sato, T.; Nakamura, T.; Sawa, C.; Hasegawa, D.; Ando, H.; Aratani, S.; Yagishita, N.; Fujii, R.; et al. Fucoidan Therapy Decreases the Proviral Load in Patients with Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type-1-Associated Neurological Disease. Antivir. Ther. 2011, 16, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, L.A.; Meyer, B.J.; Fitton, J.H.; Winberg, P. Oral Supplementation with Algal Sulphated Polysaccharide in Subjects with Inflammatory Skin Conditions: A Randomised Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial and Baseline Dietary Differences. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatalebi, M.A.; Bokaie Jazi, S.; Yegdaneh, A.; Iraji, F.; Siadat, A.H.; Noorshargh, P. Comparative Evaluation of Gracilaria Algae 3% Cream vs Clobetasol 0.05% Cream in Treatment of Plaque Type Psoriasis: A Randomized, Split-Body, Triple-Blinded Clinical Trial. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havas, F.; Krispin, S.; Cohen, M.; Loing, E.; Farge, M.; Suere, T.; Attia-Vigneau, J. A Dunaliella Salina Extract Counteracts Skin Aging under Intense Solar Irradiation Thanks to Its Antiglycation and Anti-Inflammatory Properties. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawczynski, C.; Dittrich, M.; Neumann, T.; Goetze, K.; Welzel, A.; Oelzner, P.; Völker, S.; Schaible, A.M.; Troisi, F.; Thomas, L.; et al. Docosahexaenoic Acid in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Cross-over Study with Microalgae vs. Sunflower Oil. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, H.; Yoshida, N.; Kakuma, T.; Toyomasu, K. Effect of Chlorella Ingestion on Oxidative Stress and Fatigue Symptoms in Healthy Men. Kurume Med. J. 2017, 64, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Hassinger, L.; Davis, J.; Devor, S.T.; DiSilvestro, R.A. A Randomized, Double Blind, Placebo Controlled Study of Spirulina Supplementation on Indices of Mental and Physical Fatigue in Men. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 67, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalafati, M.; Jamurtas, A.Z.; Nikolaidis, M.G.; Paschalis, V.; Theodorou, A.A.; Sakellariou, G.K.; Koutedakis, Y.; Kouretas, D. Ergogenic and Antioxidant Effects of Spirulina Supplementation in Humans. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.-K.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Hsu, J.-J.; Yang, Y.-K.; Chou, H.-N. Preventive Effects of Spirulina Platensis on Skeletal Muscle Damage under Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 98, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baicus, C.; Baicus, A. Spirulina Did Not Ameliorate Idiopathic Chronic Fatigue in Four N-of-1 Randomized Controlled Trials. Phytother. Res. 2007, 21, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, T.; Nakagawa, K.; Takekoshi, H.; Higuchi, O.; Kato, S.; Kondo, M.; Kimura, F.; Miyazawa, T. Ingestion of Chlorella Reduced the Oxidation of Erythrocyte Membrane Lipids in Senior Japanese Subjects. J. Oleo Sci. 2013, 62, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrick, F.R.; McFadden, K.; Ibars, M.; Sung, C.; Moffatt, T.; Megarry, K.; Thomas, K.; Mitchell, P.; Wallace, J.M.W.; Pourshahidi, L.K.; et al. Impact of a (Poly)Phenol-Rich Extract from the Brown Algae Ascophyllum Nodosum on DNA Damage and Antioxidant Activity in an Overweight or Obese Population: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.-Y.; Lee, W.-K.; Kim, T.-H.; Ryu, Y.-K.; Park, A.; Lee, Y.-J.; Heo, S.-J.; Oh, C.; Chung, Y.-C.; Kang, D.-H. The Effects of Spirulina Maxima Extract on Memory Improvement in Those with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.; Maury, J.; Gonzalez, D.E.; Ko, J.; Xing, D.; Jenkins, V.; Dickerson, B.; Leonard, M.; Estes, L.; Johnson, S.; et al. Effects of Supplementation with a Microalgae Extract from Phaeodactylum tricornutum Containing Fucoxanthin on Cognition and Markers of Health in Older Individuals with Perceptions of Cognitive Decline. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, S.N.S.; Ryu, J.; Kim, Y.; Jeon, B.H. The Effects of Fermented Laminaria japonica on Short-Term Working Memory and Physical Fitness in the Elderly. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2018, 2018, 8109621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskell-Ramsay, C.F.; Jackson, P.A.; Dodd, F.L.; Forster, J.S.; Bérubé, J.; Levinton, C.; Kennedy, D.O. Acute Post-Prandial Cognitive Effects of Brown Seaweed Extract in Humans. Nutrients 2018, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, M.; Maury, J.; Dickerson, B.; Gonzalez, D.E.; Kendra, J.; Jenkins, V.; Nottingham, K.; Yoo, C.; Xing, D.; Ko, J.; et al. Effects of Dietary Supplementation of a Microalgae Extract Containing Fucoxanthin Combined with Guarana on Cognitive Function and Gaming Performance. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panahi, Y.; Badeli, R.; Karami, G.-R.; Badeli, Z.; Sahebkar, A. A Randomized Controlled Trial of 6-Week Chlorella Vulgaris Supplementation in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaert, F.-A.; Demais, H.; Collén, P.N. A Randomized Controlled Double-Blind Clinical Trial Comparing versus Placebo the Effect of an Edible Algal Extract (Ulva Lactuca) on the Component of Depression in Healthy Volunteers with Anhedonia. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, C.J.; Douglas, K.J.; Kang, K.; Kolarik, A.L.; Malinovski, R.; Torres-Tiji, Y.; Molino, J.V.; Badary, A.; Mayfield, S.P. Developing Algae as a Sustainable Food Source. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1029841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuellar-Bermudez, S.P.; Aleman-Nava, G.S.; Chandra, R.; Garcia-Perez, J.S.; Contreras-Angulo, J.R.; Markou, G.; Muylaert, K.; Rittmann, B.E.; Parra-Saldivar, R. Nutrients Utilization and Contaminants Removal. A Review of Two Approaches of Algae and Cyanobacteria in Wastewater. Algal Res. 2017, 24, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, K.; Ahmad, M.; Sofia; Sharma, V.K.; Lu, P.; Harvey, A.; Zafar, M.; Sultana, S.; Anyanwu, C.N. Algal Biomass as a Global Source of Transport Fuels: Overview and Development Perspectives. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2014, 24, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L. Biorefinery as a Promising Approach to Promote Microalgae Industry: An Innovative Framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 1376–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoré, E.S.J.; Muylaert, K.; Bertram, M.G.; Brodin, T. Microalgae. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, R91–R95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zhou, W.; Min, M.; Ma, X.; Ma, Y.; Chen, P.; Zheng, H.; Doan, Y.T.T.; Liu, H.; Chen, C.; et al. Mitigating Ammonia Nitrogen Deficiency in Dairy Wastewaters for Algae Cultivation. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 201, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, Y.S.H.; Abu-Shamleh, A. Harvesting of Microalgae by Centrifugation for Biodiesel Production: A Review. Algal Res. 2020, 51, 102046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, A.; Kinney, K.; Katz, L.; Berberoglu, H. Reduction of Water and Energy Requirement of Algae Cultivation Using an Algae Biofilm Photobioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 114, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, K.W.; Yap, J.Y.; Show, P.L.; Suan, N.H.; Juan, J.C.; Ling, T.C.; Lee, D.-J.; Chang, J.-S. Microalgae Biorefinery: High Value Products Perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 229, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisti, Y. Biodiesel from Microalgae. Biotechnol. Adv. 2007, 25, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh Saratale, R.; Ponnusamy, V.K.; Jeyakumar, R.B.; Sirohi, R.; Piechota, G.; Shobana, S.; Dharmaraja, J.; Lay, C.; Dattatraya Saratale, G.; Seung Shin, H.; et al. Microalgae Cultivation Strategies Using Cost–Effective Nutrient Sources: Recent Updates and Progress towards Biofuel Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 361, 127691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafarga, T.; Acién-Fernández, F.G.; Castellari, M.; Villaró, S.; Bobo, G.; Aguiló-Aguayo, I. Effect of Microalgae Incorporation on the Physicochemical, Nutritional, and Sensorial Properties of an Innovative Broccoli Soup. LWT 2019, 111, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, A.P.; Niccolai, A.; Fradinho, P.; Fragoso, S.; Bursic, I.; Rodolfi, L.; Biondi, N.; Tredici, M.R.; Sousa, I.; Raymundo, A. Microalgae Biomass as an Alternative Ingredient in Cookies: Sensory, Physical and Chemical Properties, Antioxidant Activity and in Vitro Digestibility. Algal Res. 2017, 26, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouari, N.; Abid, M.; Fakhfakh, N.; Ayadi, M.A.; Zorgui, L.; Ayadi, M.; Attia, H. Blue-Green Algae (Arthrospira platensis) as an Ingredient in Pasta: Free Radical Scavenging Activity, Sensory and Cooking Characteristics Evaluation. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 62, 811–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahl, S.; Strack, M.; Mensching, A.; Mörlein, D. Alternative Protein Sources in Western Diets: Food Product Development and Consumer Acceptance of Spirulina-Filled Pasta. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 84, 103933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarga, T.; Rodríguez-Bermúdez, R.; Morillas-España, A.; Villaró, S.; García-Vaquero, M.; Morán, L.; Sánchez-Zurano, A.; González-López, C.V.; Acién-Fernández, F.G. Consumer Knowledge and Attitudes towards Microalgae as Food: The Case of Spain. Algal Res. 2021, 54, 102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Verma, D.K.; Thakur, M.; Tripathy, S.; Patel, A.R.; Shah, N.; Utama, G.L.; Srivastav, P.P.; Benavente-Valdés, J.R.; Chávez-González, M.L.; et al. Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SCFE) as Green Extraction Technology for High-Value Metabolites of Algae, Its Potential Trends in Food and Human Health. Food Res. Int. 2021, 150, 110746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’ Brien, R.O.; Hayes, M.; Sheldrake, G.; Tiwari, B.; Walsh, P. Macroalgal Proteins: A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadam, S.U.; Tiwari, B.K.; O’Donnell, C.P. Extraction, Structure and Biofunctional Activities of Laminarin from Brown Algae. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, E.; Odenthal, K.; Nunes, N.; Fernandes, T.; Fernandes, I.A.; Pinheiro De Carvalho, M.A.A. Protein Extracts from Microalgae and Cyanobacteria Biomass. Techno-Functional Properties and Bioactivity: A Review. Algal Res. 2024, 82, 103638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosibo, O.K.; Ferrentino, G.; Udenigwe, C.C. Microalgae Proteins as Sustainable Ingredients in Novel Foods: Recent Developments and Challenges. Foods 2024, 13, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | Protein (%) | Carbohydrates (%) | Lipids (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorella vulgaris | 38 | 33 | 5 |

| Spirulina platensis | 52 | 15 | 3 |

| Soybean | 37 | 30 | 20 |

| egg | 47 | 4 | 41 |

| Algae | Preparation | Participants | Dose | Duration | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fucus vesiculosus | Powdered extract | Overweight/obese adults with elevated LDL-C | 2000 mg/d | 12 weeks | Increase in HDL-C (+9.5%), no change in LDL-C, total glycerol, triglyceride, glucose, insulin or inflammatory markers. | [26] |

| Nannochloropsis sp. | Ethanol extract capsule | Healthy adults | 1000 mg/d | 12 weeks | Increase in omega-3 index (+16%), decrease in VLDL-C (−25%), decrease in total glycerol (−3%), no change in triglyceride, LDL-C, small reductions in body weight and hip circumference. | [27] |

| Schizochytrium sp. | Oil extract capsule | Mild to moderate hypertriglyceridemia | 4000 mg/d | 14 weeks | Significant decrease in TAG (−18.9%), increase LDL-C (+4.6%), HDL-C (+4.3%), no significant change in total-C, increase in plasma EPA, DHA. | [28] |

| Schizochytrium sp. | Extract oil capsule | Healthy adults | 625 mg/d | 3 h following ingestion | Increase in serum DHA level with largest increase in vegan (+124%), lacto-ovo-vegetarian (+59%) and omnivore (+24%). | [29] |

| Ulkenia sp. | Extract oil capsule | Healthy vegetarian | 2280 mg/d | 8 weeks | Increase in RBC DHA, PE, PC, increase in PL, increase in omega-3 index. | [30] |

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Whole biomass in water | Healthy adults | 5300 mg/d | 2 weeks | Increase in total LCn-3 PUFA, increase in plasma EPA, no change in DHA. | [31] |

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa, Microchloropsis salina | Whole biomass smoothie | Healthy adults | 15,000 mg/d | 14 days | Chlorella decreased total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, Microchlorosis increased plasma EPA and EPA. | [32] |

| Ulkenia sp. | Extract oil capsule | Healthy vegetarians | 2280 mg/d | 8 weeks | Decrease in plasma triglyceride (−23%), increase in total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C. | [33] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Whole biomass tablet | Mildly hypercholesterolemic adults | 5000 mg/d | 4 weeks | Decrease in serum total cholesterol (−1.6%), triglyceride (−10.3%), VLDL-C (−11%). | [34] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Whole biomass tablet | Healthy adults | 5000 mg/d | 4 weeks | Chlorella prevented serum total cholesterol and LDL-C rise after cholesterol challenge. | [35] |

| Algae | Preparation | Participants | Dose | Duration | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyropia yezoensis | Whole biomass roasted sheets | Healthy preschool children | 1760 mg/d | 10 weeks | Significant decrease in DBP in boys and no difference of SBP and DBP in girls. | [37] |

| Undaria pinnatifida | Whole biomass in capsule | Elderly with hypertension | 3300 mg/d | 8 weeks | Decrease in SBP and DBP, decrease in total cholesterol in hypercholestolemic subgroups (−8%). | [38] |

| Algae | Preparation | Participants | Dose | Duration | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa | Whole biomass tablet | Pregnant women | NR | Throughout pregnancy | Lower breast-milk dioxin and higher Ig-A levels in Chlorella group | [57] |

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa | Whole biomass tablet | Healthy, physically active | 6000 mg/d | 4 weeks | Increase in resting, non-exercise state sIgA | [58] |

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa | Whole biomass tablet | Female keno athletes | 6000 mg/d | 4 weeks | Chlorella attenuated sIgA decline during intense kendo training | [59] |

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa | Whole biomass tablet | Healthy men | 6000 mg | 4 weeks | Increase sIgA concentration and secretion rate | [60] |

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa | Extract in capsule | Healthy adults | 600 mg/d | 28 days | No enhancement in influenza antibody response overall, but improved response in participants ≤ 55 years | [24] |

| Undaria pinnatifida | Extract | Elderly adults | 1800 mg/d | 24 weeks | Enhanced antibody titers and preserved NK cell activity | [61] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Whole biomass tablet | Healthy adults | 5000 mg/d | 8 weeks | Enhanced NK cell activity, increase in IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-12 | [62] |

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa | Whole biomass tablet and extract | Chronic HCV genotype 1 patients | 3000 mg/d (1–7 d); 4500 mg/d (2–12 w); Extract: 6000 mg/d | 12 weeks | Decrease in ALT level (11/13 patients), decrease AST level (9/13 patients), improved subjective well-being | [63] |

| Porphyra tenera | Extract | Healthy adults | 2500 mg/d | 8 weeks | Increased NK cell activity | [64] |

| Undaria pinnatifida | Whole biomass | Herpes patients | Active infection: 22,400 mg/d; Maintenance 1120 mg/d | Active phase: 10 days, maintenance up to 24 months | Active infection patients experienced faster lesion healing and reduced pain; latent patients had complete inhibition of outbreaks during maintenance period | [65] |

| Red seaweed (species NR) | Nasal spray | Children with acute phase symptoms of cold for <48 h | 0.84 mL/d | 7 days | Decrease in time to symptom clearance, decrease in viral load, prevention of secondary viral infections | [66] |

| Cladosiphon okamuranus | Extract | HAM/TSP patients | 6000 mg/d | 6–13 months | Decrease in HTLV-1 proviral load (42.4%) | [67] |

| Gracilaria sp. | Extract | Adults with inflammatory skin conditions | 2000 mg | 6 weeks | Improved skin symptoms | [68] |

| Gracilaria sp. | Whole biomass cream | Mild to moderate plaque psoriasis patients | Once daily | 8 weeks | Improved PASI and PGA | [69] |

| Dunaliella salina | Extract cream | Female with intense sun exposure | 1% extract in cream | 56 days | Reduction in skin glycation, inflammation, wrinkles and redness, improve in skin reactivity | [70] |

| Laminaria japonica | Extract | Mild to moderate atopic dermatitis patients | 1000 mg/d | 8 weeks | Decrease in scoring atopic dermatitis, transepidermal water loss and increase skin hydration, improved clinical symptoms | [71] |

| Algae | Preparation | Participants | Dose | Duration | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parachlorella beijerinckii | Whole biomass tablet | Healthy male | 6000 mg/d | 4 weeks | Increased antioxidant capacity and decrease in MDA in resting condition | [72] |

| Spirulina platensis | Whole biomass tablet | Healthy male | 3000 mg/d | 8 weeks | Increase in exercise output on cross trainer machine after 1-week supplementation; improvement in Uchida–Kraepelin test (UKT) after 4-week and 8-week supplementation; improvement in Multidimensional Assessment of Fatigue Test | [73] |

| Spirulina platensis | Whole biomass capsule | Moderately trained male | 6000 mg/d | 4 weeks | Increased time to fatigue, decreased carbohydrate oxidation rate, increased fat oxidation rate; higher GSH levels; no increase in TBARS level after exercise | [74] |

| Spirulina platensis | Whole biomass capsule | Healthy adults | 7500 mg/d | 3 weeks | Decreased MDA level, LDH; larger increases in OSD, GPx; decrease in CK (−28.8%); increased time to exhaustion | [75] |

| Spirulina platensis | Whole biomass capsule | Idiopathic chronic fatigue patient | 3000 mg/d | 4 weeks | No difference in scores of fatigue (self-evaluated) | [76] |

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa | Whole biomass tablet | Healthy senior | 8000 mg/d | 2 months | Decrease in erythrocyte PLOOH, increase in erythrocyte and plasma lutein | [77] |

| Ascophyllum nodosum | Extract | Overweight/obese adults | 400 mg/d | 8 weeks | Decrease in basal DNA damage in obese group, decrease in TOC in women | [78] |

| Algae | Preparation | Participants | Dose | Duration | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spirulina maxima | Extract | Mild cognitive impaired patients | 1000 mg/d | 12 weeks | Enhanced visual learning and visual memory test results | [79] |

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Extract | Cognitive and memory declined patients | 1100 mg/d (8.8 mg fucoxanthin) | 12 weeks | Improved word recall, picture recognition reaction time, Stroop color-word test, choice reaction time, and digit vigilance test variables | [80] |

| Laminaria japonica A. | Fermented | Senior participants | 1500 mg/d | 6 weeks | improved neuropsychological test scores, including higher scores in the K-MMSE, numerical memory test, Raven test, and iconic memory; increased antioxidant activity | [81] |

| Ascophyllum nodosum and Fucus vesiculosus | Extract | Healthy | 500 mg | 3 h following ingestion | improvements to accuracy on digit vigilance and choice reaction time tasks | [82] |

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum | Extract | Experienced gamer | 4.40 mg + 500 mg guarana 8.80 mg + 500 mg guarana | 30 days | improved reaction times, reasoning, learning, executive control, attention shifting (cognitive flexibility), and impulsiveness | [83] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Extract | Major depressive disorder patients | 1800 mg/d | 6 weeks | reductions in total and subscale BDI-II and HADS scores as well as individual subscales of depression and anxiety | [84] |

| Ulva lactuca | Extract | Anhedonia patients | 6.45 mg/kg Body weight per day | 12 weeks | improvement in sleep disorders, psychomotor consequences and nutrition decreased behavior Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Self Report | [85] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Scherbinek, M.; Skurk, T. Algae and Algal Protein in Human Nutrition: A Narrative Review of Health Outcomes from Clinical Studies. Nutrients 2026, 18, 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020277

Wang Z, Scherbinek M, Skurk T. Algae and Algal Protein in Human Nutrition: A Narrative Review of Health Outcomes from Clinical Studies. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):277. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020277

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zixuan, Marie Scherbinek, and Thomas Skurk. 2026. "Algae and Algal Protein in Human Nutrition: A Narrative Review of Health Outcomes from Clinical Studies" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020277

APA StyleWang, Z., Scherbinek, M., & Skurk, T. (2026). Algae and Algal Protein in Human Nutrition: A Narrative Review of Health Outcomes from Clinical Studies. Nutrients, 18(2), 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020277