Revision of the Choices Nutrient Profiling System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Rationale and Methodology

- Classification and equivalence criteria for plant-based alternatives;

- The position on NSSs;

- Alignment of iTFA criteria with WHO guidelines; and

- Consideration of whole-grain criteria.

2.1. Classification and Equivalence Criteria for Plant-Based Alternatives

- selecting data sources to determine nutrient content and to evaluate the criteria;

- selecting qualifying nutrients based on the extent to which a serving contributes to the nutrient intake and alignment with nutritional policies;

- correcting for potential differences in the bioavailability of nutrients in animal- and plant-based foods and diets;

- defining thresholds and criteria for qualifying nutrients so that, if applied, the majority of animal-based products would comply with these criteria;

- evaluate the criteria using plant-based products to assess the applicability and discriminatory power.

2.1.1. Defining Data Sources to Determine Nutrient Content in “Healthier” Animal-Based Products

2.1.2. Selecting Qualifying Nutrients

2.1.3. Account for Differences in Bioavailability

2.1.4. Define Nutritional Equivalence Criteria

2.1.5. Evaluate Nutrition Equivalence Criteria

2.2. Non-Sugar Sweeteners

2.3. Trans-Fat

2.4. Whole Grain

- whole-grain and fiber criteria;

- whole-grain instead of fiber criteria;

- whole-grain or fiber criteria.

3. Results

3.1. Plant-Based Alternatives to Meat and Dairy

3.1.1. Determining Nutrient Content

3.1.2. Selecting Qualifying Nutrients

- for cheese products: none;

- for milk products: protein quantity, Ca, B2, B12;

- for meat products: protein quantity, Fe, Zn, B2, B12;

3.1.3. Accounting for Bioavailability Differences

- 1.

- Protein

- Although protein quality and digestibility may differ between animal-source foods and their plant-based alternatives, there are practical limitations to accounting for these differences. Plant-based alternatives are produced using a wide variety of protein sources, and food labels typically do not provide quantitative information on the specific sources used. It was decided not to correct for protein quality or digestibility.

- 2.

- Calcium

- The bioavailability of calcium in plant-based beverages varies depending on Ca salt and matrix. Heany et al. [61] reported a bioavailability (in comparison to cow’s milk) of 75% for Ca3(PO4)2. Zhao [62] reported a bioavailability of 83% for Ca3(PO4)2 but ~100% for CaCO3. Biscotti et al. [63] mentioned that myo-inositol phosphates, phytate, and oxalate may interfere, as well as other vitamins and minerals, and that sedimentation of Ca salts may limit the intake. It seems that it is possible, with optimal Ca fortification, that plant-based beverages may provide an equivalent source of Ca as cow’s milk, but, to be on the safe side, it was decided to correct for bioavailability with a factor 1/75% = 1.3.

- 3.

- Iron

- Heme iron from hemoglobin and myoglobin is abundant in meat and is also highly bioavailable and readily absorbed, since it is uninhibited when digested. Beef is, on average, the highest heme iron-rich source, with an average of approximately 58% of its total Fe content being heme iron [57]. Non-heme iron has a bioavailability of 2–20%. Heme iron is two to three times more bioavailable than non-heme iron [64]. Taking an average bioavailability of 10% for non-heme iron and 30% for heme iron, the bioavailability of iron in meat was calculated: 58% × 30% + 42% × 10% = 22%. In comparison with the bioavailability in plant-based products (fortified with 100% non-heme iron) of 10%, this resulted in a correction factor of 22%/10% = 2.2.

- 4.

- Zinc

- For meat alternatives, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) published a report [65] regarding the average daily required intake of Zn depending on phytate intake and body weight. Plant-based diets have a roughly three-fold higher phytate intake than their nonvegetarian counterparts [66]. The EFSA study found that the average body weight Zn requirement at a phytate consumption of 1200 mg/day is 12.2 mg/day compared to the 7.25 mg/day at 300 mg of phytate per day. This resulted in a correction factor of 12.2/7.25 = 1.7.

- 5.

- B2

- Bioavailability in animal-based foods is 61% and in plant-based foods it is 65% [67]. However, further studies are needed to make meaningful comparisons. Therefore, it was decided not to correct for relative bioavailability, correction factor = 1.

- 6.

- B12

- The absorption of vitamin B12 is limited and becomes dose-dependent due to saturation effects [68,69]. At daily intakes of 4–7 µg/day, intestinal absorption plateaus, with maximum uptake reaching 1.5–3 µg per meal. The bioavailability of vitamin B12 from animal-sourced foods, such as meat and milk, is consistently high—approximately 65% [67,70]. In contrast, the bioavailability from fortified plant-based foods, such as bread and rice, is lower, averaging around 50% [71,72]. This resulted in a correction factor of 65%/50% = 1.3.

3.1.4. Determining Nutrient Thresholds

3.1.5. Defining and Evaluating Equivalence Criteria

3.2. Non-Sugar Sweeteners

3.2.1. Understanding Long-Term Health Associations with NSS Consumption

3.2.2. Policies and Regulations Related to NSSs

3.2.3. Inclusion of Non-Sugar Sweeteners in the Choices NPS

- Option 1 (strictest): Products containing NSSs are limited to Choices levels 3–5. Basic food products with NSSs could not be positioned as “healthier” (levels 1–2), and discretionary foods (e.g., SSBs) would default to the lowest levels (4–5 in a 5-level FOPNL).

- Option 2 (less strict): Products containing NSSs are downgraded by one level compared to identical products without NSSs (except those already at level 5).

3.3. Trans-Fat

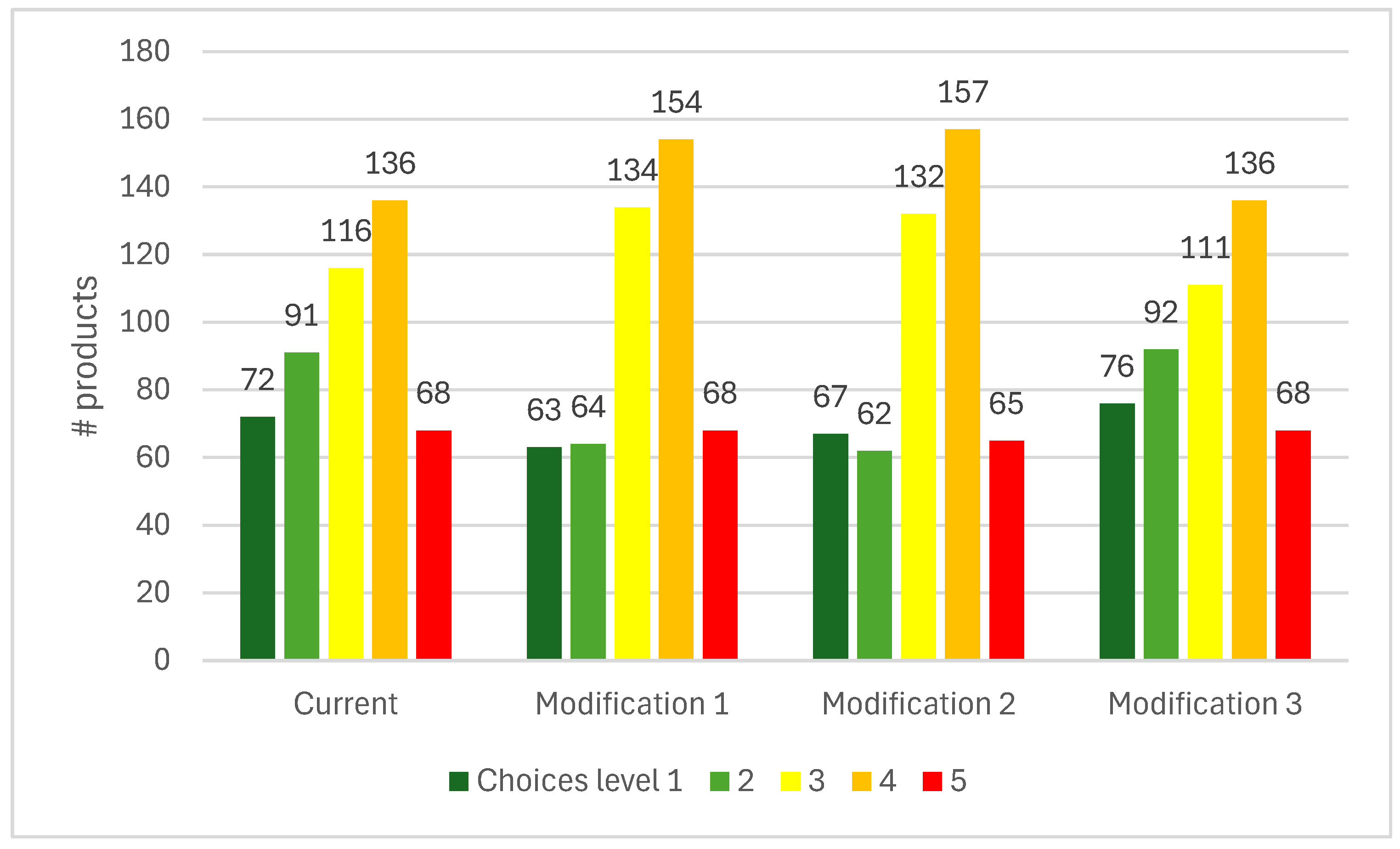

3.4. Whole Grain

3.5. The Choices 2025 Criteria

- Plant-based alternatives to meat and milk products are now assessed against the same criteria as their animal-based counterparts. These products are eligible for level 1 or 2 only if they meet the established equivalence criteria. The separate food group “non-dairy milk alternatives” has therefore become redundant. For plant-based alternatives to other foods groups (e.g., cheese, fish, eggs, etc.), no specific equivalence criteria have yet been defined, but such products should be assessed using the same criteria as their animal-based equivalents.

- Products containing non-sugar sweeteners (NSSs) are downgraded by one level compared with identical products without NSSs (except those already classified at level 5).

- For industrially produced trans-fatty acids (iTFAs), products with iTFAs ≤ 1% of total fats are eligible for levels 1–5; those with 1% < iTFAs ≤ 2% are eligible for levels 4–5; and products with iTFAs > 2% of total fats are restricted to level 5. These criteria are applicable to all product groups.

4. Discussion

4.1. Plant-Based Alternatives

4.2. Non-Sugar Sweeteners

4.3. Industrial Trans-Fatty Acids

4.4. Whole-Grain

4.5. Comparison with Other Nutrient Profiling Systems

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

4.7. Policy and Research Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Adequate intake |

| AUSNUT | Australian Food, Supplement, and Nutrient Database |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| Choices | Choices International Foundation |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| FBDGs | Food-based dietary guidelines |

| FOPNL | Front-of-pack nutrition labeling |

| HSR | Health Star Rating |

| ISC | Choices International Scientific Committee |

| iTFAs | Industrially produced trans-fatty acids |

| LMICs | Low- and middle-income countries |

| NCDs | Non-communicable diseases |

| NPS(s) | Nutrient profiling system(s) |

| NRF | Nutrient Rich Food Index |

| NSSs | Non-sugar sweeteners |

| PAHO | Pan American Health Organization |

| PRI | Population Reference Intake |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| REPLACE | WHO’s action package for eliminating industrially produced trans-fats |

| SAFA | Saturated fatty acids |

| SSBs | Sugar-sweetened beverages |

| TFAs | Trans-fatty acids |

| UNICEF | United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund |

| WGI | Whole Grain Initiative |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Naghavi, M.; Kyu, H.H.; Bhoomadevi, A.; Aalipour, M.A.; Aalruz, H.; Ababneh, H.S.; Abafita, B.J.; Abaraogu, U.O.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, M.; et al. Global Burden of 292 Causes of Death in 204 Countries and Territories and 660 Subnational Locations, 1990–2023: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 1811–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Non Communicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- World Health Organisation. Guiding Principles and Framework Manual for Front-of-Pack Labelling for Promoting Healthy Diets; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Policies to Protect Children from the Harmful Impact of Food Marketing: WHO Guideline. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240075412 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Fiscal Policies to Promote Healthy Diets: WHO Guideline. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240091016 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Labonté, M.-È.; Poon, T.; Gladanac, B.; Ahmed, M.; Franco-Arellano, B.; Rayner, M.; L’Abbé, M.R. Nutrient Profile Models with Applications in Government-Led Nutrition Policies Aimed at Health Promotion and Noncommunicable Disease Prevention: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 741–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Bend, D.L.M.; Lissner, L. Differences and Similarities between Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels in Europe: A Comparison of Functional and Visual Aspects. Nutrients 2019, 11, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tassy, M.; van Dijk, R.; Eldridge, A.L.; Mak, T.N.; Drewnowski, A.; Feskens, E.J. Nutrient Profiling Models in Low- and Middle-Income Countries Considering Local Nutritional Challenges: A Systematic Review. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2025, 9, 104530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutrition Division, Ministry of Health, Malaysia Healthier Choice Logo (HCL). Available online: https://myhcl.moh.gov.my/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Institute of Nutrition, Mahidol University Healthy Choices|Healthy Choice Nutrition Symbol Project. Available online: https://healthierlogo.com/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Indonesian Food and Drug Authority (BPOM). BPOM Regulation Number 22 Year 2019 about Nutritional Value Information on Processed Food Labels; National Agency of Drug and Food Control (Badan POM): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- PAHO/WHO Celebrates the Regulation of the Law to Promote Healthy Eating in Argentina—PAHO/WHO|Pan American Health Organization. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/29-3-2022-pahowho-celebrates-regulation-law-promote-healthy-eating-argentina (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Roodenburg, A.J.C.; Popkin, B.M.; Seidell, J.C. Development of International Criteria for a Front of Package Food Labelling System: The International Choices Programme. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodenburg, A.J.C.; Schlatmann, A.; Dötsch-Klerk, M.; Daamen, R.; Dong, J.; Guarro, M.; Stergiou, M.; Sayed, N.; Ronoh, E.; Jansen, L.; et al. Potential Effects of Nutrient Profiles on Nutrient Intakes in the Netherlands, Greece, Spain, USA, Israel, China and South-Africa. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e14721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyth, E.L.; Hendriksen, M.A.H.; Roodenburg, A.J.C.; Steenhuis, I.H.M.; van Raaij, J.M.A.; Verhagen, H.; Brug, J.; Seidell, J.C. Consuming a Diet Complying with Front-of-Pack Label Criteria May Reduce Cholesterol Levels: A Modeling Study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2012, 66, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Roodenburg, A.J.; van Ballegooijen, A.J.; Dötsch-Klerk, M.; van der Voet, H.; Seidell, J.C. Modelling of Usual Nutrient Intakes: Potential Impact of the Choices Programme on Nutrient Intakes in Young Dutch Adults. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyth, E.L.; Steenhuis, I.H.; Roodenburg, A.J.; Brug, J.; Seidell, J.C. Front-of-Pack Nutrition Label Stimulates Healthier Product Development: A Quantitative Analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smed, S.; Edenbrandt, A.K.; Jansen, L. The Effects of Voluntary Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels on Volume Shares of Products: The Case of the Dutch Choices. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2879–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Bend, D.L.M.; Jansen, L.; van der Velde, G.; Blok, V. The Influence of a Front-of-Pack Nutrition Label on Product Reformulation: A Ten-Year Evaluation of the Dutch Choices Programme. Food Chem. X 2020, 6, 100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Assum, S.; Schilpzand, R.; Lissner, L.; Don, R.; Nair, K.M.; Nnam, N.; Uauy, R.; Yang, Y.; Pekcan, A.G.; Roodenburg, A.J.C. Periodic Revisions of the International Choices Criteria: Process and Results. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tognon, G.; Beltramo, B.; Schilpzand, R.; Lissner, L.; Roodenburg, A.J.C.; Don, R.; Nair, K.M.; Nnam, N.; Hamaker, B.; Smorenburg, H. Development of the Choices 5-Level Criteria to Support Multiple Food System Actions. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konings, J.J.C.; Smorenburg, H.; Roodenburg, A.J.C. Comparison between the Choices Five-Level Criteria and Nutri-Score: Alignment with the Dutch Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.K.; Pitt, S.; Smorenburg, H.; Wolk, A.; Lissner, L. The Nutrient Profiling of Swedish Food Products—A Study of the Alignment of the Multi-Level Criteria for the Choices and Nutri-Score Systems with the Nordic Keyhole Logo. Nutrients 2025, 17, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Industries, M. for P. Boosted Health Star Ratings Get Tougher on Sugar and Salt|NZ Government. Available online: https://www.mpi.govt.nz/news/media-releases/boosted-health-star-ratings-get-tougher-on-sugar-and-salt/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- SPF Update of the Nutri-Score Algorithm for Beverages. Second Update Report from the Scientific Committee of the Nutri-Score V2-2023. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/determinants-de-sante/nutrition-et-activite-physique/documents/rapport-synthese/update-of-the-nutri-score-algorithm-for-beverages.-second-update-report-from-the-scientific-committee-of-the-nutri-score-v2-2023 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- WHO Regional Office for Europe Nutrient Profile Model: Second Edition. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2023-6894-46660-68492 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Bouvard, V.; Loomis, D.; Guyton, K.Z.; Grosse, Y.; Ghissassi, F.E.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Guha, N.; Mattock, H.; Straif, K. Carcinogenicity of Consumption of Red and Processed Meat. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1599–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, T.; Gardner, C.D.; Herrero, M.; Iannotti, L.L.; Merbold, L.; Nordhagen, S.; Mottet, A. Friend or Foe? The Role of Animal-Source Foods in Healthy and Environmentally Sustainable Diets. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Thilsted, S.H.; Willett, W.C.; Gordon, L.J.; Herrero, M.; Hicks, C.C.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Rao, N.; Springmann, M.; Wright, E.C.; et al. The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy, Sustainable, and Just Food Systems. Lancet 2025, 406, 1625–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plant-Based Retail Market Overview|GFI. Available online: https://gfi.org/marketresearch/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Dutch Food Composition Database (NEVO)|RIVM. Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/en/dutch-food-composition-database (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Swedish Food Agency The Food Database. Available online: https://www.livsmedelsverket.se/en/food-and-content/naringsamnen/livsmedelsdatabasen (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority DRV Finder Dietary Reference Values for the EU. Available online: https://multimedia.efsa.europa.eu/drvs/index.htm (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Carruba, M.O.; Ragni, M.; Ruocco, C.; Aliverti, S.; Silano, M.; Amico, A.; Vaccaro, C.M.; Marangoni, F.; Valerio, A.; Poli, A.; et al. Role of Portion Size in the Context of a Healthy, Balanced Diet: A Case Study of European Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Leyvraz, M.; Montez, J. Health Effects of the Use of Non-Sugar Sweeteners: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240046429 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Use of Non-Sugar Sweeteners: WHO Guideline. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240073616 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Mathur, P.; Bakshi, A. Effect of Non-Nutritive Sweeteners on Insulin Regulation, Glycemic Response, Appetite and Weight Management: A Systematic Review. NFS 2024, 54, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation Trans Fat. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trans-fat (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- World Health Organisation. REPLACE Trans Fat-Free. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/nutrition-and-food-safety/replace-trans-fat (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Van der Kamp, J.-W.; Jones, J.M.; Miller, K.B.; Ross, A.B.; Seal, C.J.; Tan, B.; Beck, E.J. Consensus, Global Definitions of Whole Grain as a Food Ingredient and of Whole-Grain Foods Presented on Behalf of the Whole Grain Initiative. Nutrients 2022, 14, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.-C.; Tong, X.; Xu, J.-Y.; Han, S.-F.; Wan, Z.-X.; Qin, J.-B.; Qin, L.-Q. Whole-Grain Intake and Total, Cardiovascular, and Cancer Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies12. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissock, K.R.; Neale, E.P.; Beck, E.J. Whole Grain Food Definition Effects on Determining Associations of Whole Grain Intake and Body Weight Changes: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, E.Q.; Chacko, S.A.; Chou, E.L.; Kugizaki, M.; Liu, S. Greater Whole-Grain Intake Is Associated with Lower Risk of Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Weight Gain. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, W.; Bao, W.; Wang, X. Association of Whole Grain Intake with All-Cause, Cardiovascular, and Cancer Mortality: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis from Prospective Cohort Studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferruzzi, M.G.; Jonnalagadda, S.S.; Liu, S.; Marquart, L.; McKeown, N.; Reicks, M.; Riccardi, G.; Seal, C.; Slavin, J.; Thielecke, F.; et al. Developing a Standard Definition of Whole-Grain Foods for Dietary Recommendations: Summary Report of a Multidisciplinary Expert Roundtable Discussion. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.B. Review of Whole Grain and Dietary Fiber Recommendations and Intake Levels in Different Countries. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissock, K.R.; Vieux, F.; Mathias, K.C.; Drewnowski, A.; Seal, C.J.; Masset, G.; Smith, J.; Mejborn, H.; McKeown, N.M.; Beck, E.J. Aligning Nutrient Profiling with Dietary Guidelines: Modifying the Nutri-Score Algorithm to Include Whole Grains. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, C.; Kissock, K.R.; Barrett, E.M.; Beck, E.J. Aligning Front-of-Pack Labelling with Dietary Guidelines: Including Whole Grains in the Health Star Rating. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 2025–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AUSNUT 2011–2013; Australian Food, Supplement and Nutrient Database (AUSNUT) 2011–2013. Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ): Canberra, Australia, 2014.

- Galea, L.M.; Beck, E.J.; Probst, Y.C.; Cashman, C.J. Whole Grain Intake of Australians Estimated from a Cross-Sectional Analysis of Dietary Intake Data from the 2011–13 Australian Health Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissock, K.R.; Neale, E.P.; Beck, E.J. The Relevance of Whole Grain Food Definitions in Estimation of Whole Grain Intake: A Secondary Analysis of the National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey 2011–2012. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1307–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaucheron, F. Milk and Dairy Products: A Unique Micronutrient Combination. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2011, 30, 400S–409S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milk Production|Gateway to Dairy Production and Products. Available online: https://www.fao.org/dairy-production-products/production/milk-production/en (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Cimmino, F.; Catapano, A.; Petrella, L.; Villano, I.; Tudisco, R.; Cavaliere, G. Role of Milk Micronutrients in Human Health. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2023, 28, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Reijden, O.L.; Zimmermann, M.B.; Galetti, V. Iodine in Dairy Milk: Sources, Concentrations and Importance to Human Health. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 31, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro Cardoso Pereira, P.M.; dos Reis Baltazar Vicente, A.F. Meat Nutritional Composition and Nutritive Role in the Human Diet. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comerford, K.B.; Miller, G.D.; Boileau, A.C.; Masiello Schuette, S.N.; Giddens, J.C.; Brown, K.A. Global Review of Dairy Recommendations in Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 671999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cereals & Grains Association. Available online: https://www.cerealsgrains.org/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Passarelli, S.; Free, C.M.; Shepon, A.; Beal, T.; Batis, C.; Golden, C.D. Global Estimation of Dietary Micronutrient Inadequacies: A Modelling Analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e1590–e1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P.; Dowell, M.S.; Rafferty, K.; Bierman, J. Bioavailability of the Calcium in Fortified Soy Imitation Milk, with Some Observations on Method123. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 1166–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Martin, B.R.; Weaver, C.M. Calcium Bioavailability of Calcium Carbonate Fortified Soymilk Is Equivalent to Cow’s Milk in Young Women12. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 2379–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscotti, P.; Tucci, M.; Angelino, D.; Vinelli, V.; Pellegrini, N.; Del Bo’, C.; Riso, P.; Martini, D. Effects of Replacing Cow’s Milk with Plant-Based Beverages on Potential Nutrient Intake in Sustainable Healthy Dietary Patterns: A Case Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, S.; Altunkaynak, T.B.; Yazici, F. A Note on the Total and Heme Iron Contents of Ready-to-Eat Doner Kebabs. Meat Sci. 2004, 67, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietary Reference Values for Zinc|EFSA. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/3844 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Foster, M.; Samman, S. 38—Implications of a plant-based diet on zinc requirements and nutritional status. In Vegetarian and Plant-Based Diets in Health and Disease Prevention; Mariotti, F., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 683–713. ISBN 978-0-12-803968-7. [Google Scholar]

- Chungchunlam, S.M.S.; Moughan, P.J. Comparative Bioavailability of Vitamins in Human Foods Sourced from Animals and Plants. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 11590–11625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogiatzoglou, A.; Smith, A.D.; Nurk, E.; Berstad, P.; Drevon, C.A.; Ueland, P.M.; Vollset, S.E.; Tell, G.S.; Refsum, H. Dietary Sources of Vitamin B-12 and Their Association with Plasma Vitamin B-12 Concentrations in the General Population: The Hordaland Homocysteine Study2. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.H. Bioavailability of Vitamin B12. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2013, 80, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melse-Boonstra, A. Bioavailability of Micronutrients from Nutrient-Dense Whole Foods: Zooming in on Dairy, Vegetables, and Fruits. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, M.G.; Buchholz, B.A.; Miller, J.W.; Haack, K.W.; Green, R.; Allen, L.H. Vitamin B12 Added as a Fortificant to Flour Retains High Bioavailability When Baked in Bread. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2019, 438, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyrwa, Y.W.; Palika, R.; Boddula, S.; Boiroju, N.K.; Madhari, R.; Pullakhandam, R.; Thingnganing, L. Retention, Stability, Iron Bioavailability and Sensory Evaluation of Extruded Rice Fortified with Iron, Folic Acid and Vitamin B12. Matern. Child Nutr. 2020, 16, e12932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Gidding, S.S.; Steffen, L.M.; Johnson, R.K.; Reader, D.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; on behalf of the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee of the Council on Nutrition; Physical Activity and Metabolism; Council on Arteriosclerosis; et al. Nonnutritive Sweeteners: Current Use and Health Perspectives: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1798–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosdøl, A.; Vist, G.E.; Svendsen, C.; Dirven, H.; Lillegaard, I.T.L.; Mathisen, G.H.; Husøy, T. Hypotheses and Evidence Related to Intense Sweeteners and Effects on Appetite and Body Weight Changes: A Scoping Review of Reviews. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Smith, C.M.; De Ferranti, S.D.; Cochran, W.J.; Committee on Nutrition, Section on Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition; Abrams, S.A.; Fuchs, G.J., III; Kim, J.H.; Lindsey, C.W.; Magge, S.N.; Rome, E.S.; et al. The Use of Nonnutritive Sweeteners in Children. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20192765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Manual on Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxation Policies to Promote Healthy Diets. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240056299 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- UNICEF Advocacy Packages for Food Environment Policies|UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/documents/advocacy-packages-food-environment-policies (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Temple, N.J.; Steyn, N.P. 11. Sugar and Health: A Food-Based Dietary Guideline for South Africa. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 26, S100–S104. [Google Scholar]

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines Booklet—2022; Ethiopian Public Health Institute: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. National Guidelines for Healthy Diets and Physical Activity; Ministry of Health: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nutrient Profile Model for the WHO African Region: A Tool for Implementing WHO Recommendations on the Marketing of Foods and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290234401 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Pan American Health Organization. Pan American Health Organization Nutrient Profile Model; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-92-75-11873-3. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxation in the Region of the Americas; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, L.D.; Sharma, S.; Gildengorin, G.; Yoshida, S.; Braff-Guajardo, E.; Crawford, P. Policy Improves What Beverages Are Served to Young Children in Child Care. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swedish Food Agency The Keyhole. Available online: https://www.livsmedelsverket.se/en/food-habits-health-and-environment/nyckelhalet (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Health Star Rating System. Available online: https://www.healthstarrating.gov.au/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Health Promotion Board. A Handbook on Nutrition Labelling (Singapore); Health Promotion Board: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, E.V.; Azam-Ali, S.; McCullough, F.; Roy Mitra, S. The Nutrition Transition in Malaysia; Key Drivers and Recommendations for Improved Health Outcomes. BMC Nutr. 2020, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutrition and Labelling|Codex Alimentarius FAO-WHO. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/thematic-areas/nutrition-labelling/en/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Fulgoni, V.L.; Keast, D.R.; Drewnowski, A. Development and Validation of the Nutrient-Rich Foods Index: A Tool to Measure Nutritional Quality of Foods. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1549–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.; Moshtaghian, H.; Lindroos, A.K.; Hallström, E.; Winkvist, A. Nutrient Quality of Beverages: Comparing the Nordic Keyhole, Nutri-Score and Nutrient Rich Food Indices. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 76, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Countdown to 2023: WHO 5-Year Milestone Report on Global Trans Fat Elimination 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240089549 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Price, E.J.; Barrett, E.M.; Batterham, M.J.; Beck, E.J. Exploring the Reporting, Intake and Recommendations of Primary Food Sources of Whole Grains Globally: A Scoping Review. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 132, 1365–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Choices Product Group | Database | Product Groups in Dutch and Swedish Databases and Selection Criteria | N Total | n “Healthier” | % “Healthier” |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheese products | Combined | 114 | 9 | 8 | |

| Dutch | Cheese products (73), excluded one hard cheese product from the “healthier” subset 1 | 73 | 3 | 4 | |

| Swedish | Toppings (84) (descriptions translated to English and selected only cheese products) excluded one hard cheese product from the “healthier” subset 1 | 41 | 6 | 15 | |

| Milk products | Combined | 183 | 48 | 26 | |

| Dutch | Milk products (132) (eliminated human milk and dried milk products) | 129 | 34 | 26 | |

| Swedish | Milk products (73) (descriptions translated to English and eliminated human milk, dried milk products, and plant-based dairy alternatives) | 54 | 14 | 26 | |

| Processed meat and meat products | Combined | 511 | 298 | 58 | |

| Dutch | Meat and poultry (216), Cold meat cuts (65), excluded products containing liver, kidney, tongue, or brain | 250 | 139 | 56 | |

| Swedish | Chicken/bird (44), Meat (174), Sausage (43) | 261 | 159 | 61 | |

| Plant-based milk alternatives | Combined | 42 | 30 | 71 | |

| Dutch | Dairy and meat alternatives (62) (manually selected milk alternatives) | 28 | 19 | 68 | |

| Swedish | Milk products (73) (descriptions translated to English and selected plant-based dairy alternatives) | 14 | 11 | 26 | |

| Plant-based meat alternatives | Combined | 104 | 70 | 67 | |

| Dutch | Dairy and meat alternatives (62) (manually selected meat alternatives) | 32 | 23 | 72 | |

| Swedish | Quorn, soy protein, and vegetarian products (72) | 72 | 47 | 65 |

| Choices Food Groups | Whole Grain % (Dry Weight) | Fiber Threshold (g/100 g) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | |

| Plain noodles and pasta, flavored noodles and pasta, breads, breakfast cereals | 50 | 25 | 6.0 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 0.5 | ||

| Grains | 100 | 50 | 25 | 6.0 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 0.5 | |

| Choices Product Group | Vitamin | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAFA | Sugar | Na | Protein | Ca | Fe | I | K | Mg | P | Se | Zn | A | D | B2 | B12 | |

| g | g | mg | g | mg | mg | µg | mg | mg | mg | µg | mg | RE µg | µg | mg | µg | |

| Cheese products | 4.1 | 3.9 | 268 | 9.7 | 100 | 0.2 | 8 | 105 | 8 | 138 | 3 | 0.4 | 86 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.39 |

| Dutch FCDB | 4.6 | 4.5 | 307 | 7.0 | 119 | 0.4 | 4 | 93 | 9 | 119 | 0 | 0.5 | 119 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.39 |

| Swedish FCDB | 3.8 | 3.6 | 248 | 11.1 | 91 | 0.1 | 10 | 111 | 8 | 147 | 4 | 0.4 | 70 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.39 |

| Milk products | 0.4 | 4.3 | 44 | 4.7 | 119 | 0.1 | 14 | 139 | 11 | 99 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 9 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.33 |

| Dutch FCDB | 0.4 | 4.3 | 44 | 4.4 | 122 | 0.1 | 14 | 136 | 11 | 94 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 10 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.31 |

| Swedish FCDB | 0.4 | 4.3 | 43 | 5.6 | 111 | 0.0 | 13 | 146 | 11 | 112 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 6 | 0.55 | 0.16 | 0.38 |

| Processed meat and meat products | 2.3 | 0.1 | 138 | 23.0 | 11 | 1.9 | 6 | 359 | 26 | 218 | 11.0 | 3.3 | 20 | 0.43 | 0.22 | 1.42 |

| Dutch FCDB | 2.4 | 0.2 | 123 | 24.2 | 11 | 1.6 | 4 | 417 | 26 | 227 | 11.6 | 3.4 | 23 | 0.47 | 0.17 | 1.58 |

| Swedish FCDB | 2.2 | 0.1 | 150 | 22.0 | 11 | 2.2 | 8 | 308 | 26 | 210 | 10.5 | 3.1 | 18 | 0.39 | 0.26 | 1.28 |

| Vitamin | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Ca | Fe | I 1 | K 1 | Mg 1 | P 1 | Se 1 | Zn | A | D 1 | B2 | B12 1 | |

| g | mg | mg | µg | mg | mg | mg | µg | mg | RE µg | µg | mg | µg | |

| PRIs or AIs | 58 2 | 1000 | 13.5 | 150 | 3500 | 325 | 550 | 70 | 11.5 | 700 | 15 | 1.6 | 4 |

| Contribution to PRIs or AIs | % | ||||||||||||

| 60 g cheese products | 10 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 15 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 6 |

| 200 g milk products | 16 | 24 | 1 | 18 | 8 | 7 | 36 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 20 | 16 |

| 100 g meat products | 40 | 1 | 14 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 40 | 16 | 28 | 3 | 3 | 13 | 35 |

| Protein | Ca | Fe | Zn | B2 | B12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g | mg | mg | mg | mg | µg | |

| Mean content (and standard deviation) of qualifying nutrients in “healthier” products | ||||||

| Milk products | 4.7 (2.9) | 119 (39) | 0.159 (0.042) | 0.329 (0.163) | ||

| Processed meat and meat products | 23.0 (4.3) | 1.9 (1.2) | 3.3 (1.8) | 0.216 (0.106) | 1.417 (1.411) | |

| Threshold values for animal-based products calculation method: Mean–standard deviation and rounded (B12: threshold = average × 70% and rounded) | ||||||

| Milk products | 2 | 80 | 0.1 | 0.2 | ||

| Processed meat and meat products | 19 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 1.0 | |

| Bioavailability correction factor for plant-based products | ||||||

| 1 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Threshold values for plant-based products | ||||||

| Plant-based milk alternatives | 2 | 100 | 0.1 | 0.3 | ||

| Plant-based meat alternatives | 19 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 0.1 | 1.3 | |

| % of “healthier” products that had a nutrient content > threshold value | ||||||

| Milk products | 90 | 88 | 94 | 81 | ||

| Processed meat and meat products | 90 | 91 | 85 | 93 | 55 | |

| Plant-based milk alternatives | 50 | 63 | 57 | 67 | ||

| Plant-based meat alternatives | 24 | 74 | 19 | 49 | 0 | |

| Nutritional Equivalence Criteria | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Option | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Milk products | 75% | 90% | 90% | 90% |

| Processed meat and meat products | 48% | 74% | 87% | 89% |

| Plant-based milk alternatives | 20% | 40% | 40% | 50% |

| Plant-based meat alternatives | 0% | 4% | 11% | 25% |

| Geographical Region | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|

| Global | WHO has developed an NPS and taxation policy strategies applicable across regions [26,76]. UNICEF recommends improvements to FBDGs and child nutrition policies [77]. |

| Africa | FBDGs for South Africa [78], Ethiopia [79], and Kenya [80] do not address NSSs. WHO Africa’s NPS prohibits marketing of NSS-containing products [81]. |

| Americas | Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)’s NPS includes NSS-containing products in regulatory, restriction, and taxation policies [82]. Chile taxes SSBs, including NSS-sweetened beverages [83]. Some states in the USA restrict sweetened beverages in schools and marketing to children [84]. |

| Europe | WHO Europe’s NPS restricts marketing to or being offered to children in schools of NSS-containing products [26]. The Nordic Keyhole label excludes products with NSSs [85]. Nutri-Score penalizes NSSs in scoring [25]. |

| Oceania | NSSs are not explicitly addressed in the Australian and New Zealand Health Star Rating system. Suggestions include clearer FBDG guidance on sweeteners to prevent reformulation toward NSSs [86]. |

| Southeast Asia | In Singapore, products with NSSs can carry the Healthier Choice Symbol but are not allowed in schools [87]. Malaysia’s SSB tax does not apply to NSSs [88]. |

| Proposed Choices Level | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Grand Total | ||

| current Choices level | 1 | 10 | 1 | 11 | |||

| 2 | 28 | 12 | 3 | 43 | |||

| 3 | 25 | 10 | 2 | 37 | |||

| 4 | 31 | 6 | 37 | ||||

| 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 45 | 64 | |

| Grand Total | 13 | 31 | 29 | 63 | 56 | 192 | |

| Food Group | L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAFA | Sodium | Sugar | Fiber | Energy | SAFA | Sodium | Sugar | Fiber | Energy | SAFA | Sodium | Sugar | Fiber | Energy | SAFA | Sodium | Sugar | Fiber | Energy | ||

| g/100 g | kcal/100 g | g/100 g | kcal/100 g | g/100 g | kcal/100 g | g/100 g | kcal/100 g | ||||||||||||||

| Basic food groups | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Fruits and vegetables | Fresh fruits and vegetables | All compliant | |||||||||||||||||||

| Processed vegetables | 0.10 | 7.0 | 1 | 0.25 | 8.5 | 0.9 | 0.40 | 10.0 | 0.8 | 0.65 | 11.0 | 0.7 | |||||||||

| Processed fruit | 1.1 | 11.5 | 1 | 2 | 12.5 | 0.9 | 3 | 14.0 | 0.8 | 4 | 19.0 | 0.7 | |||||||||

| Processed beans and legumes | 0.20 | 5.7 | 3.5 | 0.33 | 7.5 | 3.2 | 0.40 | 10.0 | 1.7 | 0.43 | 10.5 | 1.1 | |||||||||

| Water | Plain water, tea and coffee | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Nuts and seeds | Nuts and seeds | 10.0 | 0.10 | 7.5 | 16.0 | 0.43 | 14.0 | 18.0 | 0.55 | 30.0 | 20.0 | 0.73 | 36.0 | ||||||||

| Sources of complex carbohydrates | Plain tubers used as staple | All compliant | |||||||||||||||||||

| Processed tubers used as staple | 1.1 | 0.10 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 0.35 | 6.5 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 0.40 | 10.0 | 1.5 | 8.0 | 1.60 | 12.0 | 0.8 | |||||

| Plain noodles and pasta | 0.10 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 0.20 | 4.2 | 2.8 | 0.48 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.80 | 6.0 | 0.5 | |||||||||

| Flavored noodles and pasta | 2.0 | 0.50 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 3.5 | 0.93 | 4.2 | 2.8 | 6.5 | 1.20 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 8.0 | 1.50 | 6.0 | 0.5 | |||||

| Grains | 1.2 | 0.10 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 1.5 | 0.23 | 6.0 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 0.48 | 10.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 1.40 | 12.0 | 0.5 | |||||

| Bread | 1.1 | 0.32 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 1.8 | 0.40 | 6.5 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 0.48 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 0.85 | 15.0 | 0.5 | |||||

| Breakfast cereals | 3.0 | 0.40 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 3.2 | 0.50 | 14.0 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 0.64 | 15.0 | 1.0 | 4.2 | 0.68 | 26.0 | 0.5 | |||||

| Meat and alternatives, fish, poultry, eggs | Unprocessed meat, poultry, eggs | 3.2 | 0.15 | 3.7 | 0.17 | 5.3 | 0.40 | 7.5 | 0.68 | ||||||||||||

| Processed meat and meat products and plant-based meat alternatives 1 | 5.0 | 0.45 | 6.0 | 0.60 | 8.0 | 0.68 | 10.0 | 1.30 | |||||||||||||

| Fresh, frozen, or processed seafood | 6.0 | 0.30 | 6.5 | 0.43 | 7.0 | 0.68 | 7.5 | 1.10 | |||||||||||||

| Insects | 3.2 | 0.20 | 3.2 | 0.20 | |||||||||||||||||

| Dairy and alternatives | Milk (products) and plant-based milk alternatives 1 | 1.4 | 6.0 | 1.7 | 8.0 | 2.7 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 14.0 | ||||||||||||

| Cheese (products) and plant-based cheese alternatives | 7.5 | 0.40 | 8.5 | 0.50 | 10.0 | 0.60 | 19.0 | 1.20 | 6.0 | ||||||||||||

| Oils, fats, spreads | Oils, fats, spreads | 16.0 | 0.10 | 30.0 | 0.35 | 36.0 | 0.52 | 55.0 | 0.75 | ||||||||||||

| Meals | Main meals | 2.0 | 0.24 | 5.0 | 2.4 | 190 and 600 2 | 3.0 | 0.34 | 7.0 | 1.4 | 200 and 600 2 | 4.0 | 0.40 | 10.0 | 1.0 | 225 | 5.0 | 0.53 | 11.0 | 0.8 | 275 |

| Sandwiches and rolls | 2.0 | 0.45 | 5.0 | 2.4 | 190 and 350 2 | 3.0 | 0.57 | 7.0 | 1.4 | 215 and 350 2 | 4.0 | 0.62 | 10.0 | 1.0 | 225 | 5.0 | 0.80 | 11.0 | 0.8 | 275 | |

| Soups | 1.1 | 0.25 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 0.29 | 5.0 | 3.5 | 0.35 | 9.0 | 4.0 | 0.39 | 10.0 | |||||||||

| Discretionary (or non-basic) food groups | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sauces | Meal sauces | 1.1 | 0.40 | 6 | 1.3 | 0.70 | 8 | 2.5 | 2.20 | 16 | 6.0 | 4.50 | 26 | ||||||||

| Emulsified sauces | 3 | 0.70 | 10 | 350 | 4.5 | 1.00 | 12 | 380 | 6 | 1.20 | 17 | 550 | 8 | 1.80 | 21 | 650 | |||||

| Dark sauces | 3.00 | 16 | 5.50 | 20 | 6.50 | 25.5 | 7.75 | 35 | |||||||||||||

| Other sauces (water-based) | 0.75 | 16.0 | 100 | 0.80 | 25.0 | 130 | 0.90 | 31.0 | 150 | 1.08 | 39.0 | 190 | |||||||||

| Snacks | Savory snacks | 4.0 | 0.40 | 4.0 | 500 | 7.0 | 0.79 | 6.5 | 535 | 9.0 | 0.88 | 9.0 | 540 | 13.0 | 1.00 | 16.0 | 570 | ||||

| Sweet snacks | 6.0 | 0.20 | 20.0 | 220 | 12.0 | 0.22 | 45.0 | 475 | 16.5 | 0.31 | 55.0 | 510 | 20.0 | 0.41 | 62.0 | 550 | |||||

| Liquids | Fruit and vegetable juices | 5.0 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 11.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Beverages | 2.5 | 5.5 | 8.0 | 11.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Other | All other products | 1.1 or 10 3 | 0.10 | 2.5 or 10 3 | 1.1 or 10 3 | 0.10 | 2.5 or 10 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Equivalence criteria for plant-based alternatives 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Protein | Ca | Fe | Zn | B2 | B12 | ||||||||||||||||

| g | mg | mg | mg | mg | µg | ||||||||||||||||

| Plant-based milk alternatives | 2 | 100 | 0.1 | 0.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Plant-based meat alternatives | 19 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 0.1 | 1.3 | ||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Smorenburg, H.; Kissock, K.R.; Beck, E.J.; Mathur, P.; Hamaker, B.; Lissner, L.; Marostica, M.R., Jr.; Nnam, N.; Takimoto, H.; Roodenburg, A.J.C. Revision of the Choices Nutrient Profiling System. Nutrients 2026, 18, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020258

Smorenburg H, Kissock KR, Beck EJ, Mathur P, Hamaker B, Lissner L, Marostica MR Jr., Nnam N, Takimoto H, Roodenburg AJC. Revision of the Choices Nutrient Profiling System. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020258

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmorenburg, Herbert, Katrina R. Kissock, Eleanor J. Beck, Pulkit Mathur, Bruce Hamaker, Lauren Lissner, Mario R. Marostica, Jr., Ngozi Nnam, Hidemi Takimoto, and Annet J. C. Roodenburg. 2026. "Revision of the Choices Nutrient Profiling System" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020258

APA StyleSmorenburg, H., Kissock, K. R., Beck, E. J., Mathur, P., Hamaker, B., Lissner, L., Marostica, M. R., Jr., Nnam, N., Takimoto, H., & Roodenburg, A. J. C. (2026). Revision of the Choices Nutrient Profiling System. Nutrients, 18(2), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020258