Abstract

Background/Objectives: Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB) is a severe congenital genodermatosis characterized by skin and mucosa fragility, chronic inflammation, recurrent infections and high nutritional demands due to increased metabolism and epithelial barrier-related losses, placing patients at risk of zinc deficiency. We aimed to investigate the clinical relevance and biochemical determinants of zinc deficiency as a potentially modifiable contributor to disease burden in RDEB. Methods: In this cross-sectional study (n = 84), serum zinc levels were analyzed in association with sex, age, disease severity, percentage of body surface area (BSA) affected, inflammatory markers, infection burden, and common clinical complications including anemia and growth impairment. Results: Zinc deficiency, defined as levels below 670 µg/L, was identified in 35% of patients and became more frequent after age 5 and during adulthood, particularly among those with more severe disease. Deficiency was strongly associated with anemia, inflammation, infection burden, growth impairment, and extensive skin involvement. A revised cutoff of 780 µg/L is proposed, showing improved diagnostic performance for identifying patients at risk of systemic complications, and offering a more suitable threshold for starting preventive supplementation. Multivariate logistic modeling confirmed that low serum zinc independently predicted anemia risk, alongside transferrin saturation and C- reactive protein levels. Serum albumin was identified as the strongest determinant of zinc levels, partially mediating the effects of inflammation and skin involvement. Conclusions: These findings identify serum zinc as a clinically relevant marker of nutritional status and complication burden in RDEB. While no causal or therapeutic effects can be inferred from this cross-sectional study, the strong and biologically plausible associations observed suggest a rationale for systematic monitoring and correction of zinc deficiency as part of comprehensive supportive care, and warrant prospective studies to assess clinical benefit.

1. Introduction

Patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB) suffer from recurrent, painful wounds from birth as a direct consequence of the hereditary loss of function of type VII collagen anchoring fibrils [1]. Beyond this cutaneous fragility, this genetic disorder evolves into a chronic multisystemic condition in which persistent inflammation [2,3] and infection [4,5] not only exacerbate epithelial damage but also give rise to numerous complications including early-onset malnutrition that further fuels disease progression [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Advanced therapies are emerging as potential treatments for RDEB [6,12,13]. Although recently approved local gene therapies represent a major milestone, their long-term efficacy, systemic benefits, and accessibility remain uncertain [14,15,16]. Crucially, their therapeutic impact may be limited by systemic factors associated with disease severity. This underscores the need for safe, systemic approaches that address modifiable contributors to disease burden before severe or irreversible stages develop. Inflammation and malnutrition are key candidates, as both are well known to exacerbate disease manifestations and compromise tissue homeostasis and repair. Ideally, such strategies—simple, affordable, and applicable across disease stages and severities—could complement both current and future therapies, ultimately improving prognosis and quality of life.

Zinc is an essential trace element involved in tissue repair, hematopoiesis, growth, immune function, endocrine homeostasis, and epithelial barrier maintenance [17,18,19]. Its ubiquity and multifunctionality are evidenced by its role as a cofactor for numerous enzymes. These include key proteins with fundamental cellular functions such as protein kinase C, caspase 6 and 8, superoxide dismutase, matrix metalloproteinases, and DNA methyltransferases [20]. Additionally, zinc supports the activity of more than 1000 transcription factors, including zinc finger proteins like GATA, Krüppel-like factor family members, or Specificity Protein 1 like proteins [20]. Zinc deficiency can therefore lead to a broad range of systemic effects, including impaired wound healing, growth delay, sarcopenia, anemia, susceptibility to infections, anorexia, inflammation, and psychological symptoms [17,18,21], all of which are common in RDEB patients with multifactorial malnutrition [7,8,22,23,24].

The skin contains approximately 5% of the body’s total zinc [25]. In RDEB, zinc requirements are heightened due to continuous losses from recurrent and often extensive skin wounds, alongside an increased need to support tissue repair and immune defense. Systemic inflammation further contributes to functional zinc deficiency by promoting hepatic sequestration, reducing intestinal absorption, and increasing excretion in response to cytokines such as IL6 [19]. At the same time, reduced oral intake due to odynophagia, mucosal damage, and feeding difficulties limits dietary zinc supply in many patients. Unlike iron, zinc lacks substantial tissue storage [26]; thus, even transient imbalances may impair essential biological functions. In chronic settings such as RDEB, a persistent inflammatory and catabolic state, compounded by inadequate intake, places patients at particularly high risk for zinc deficiency, which may, in turn, exacerbate disease progression [7,22,27,28].

Despite zinc’s recognized importance, its deficiency and clinical impact in RDEB are poorly defined, and no evidence-based, standardized supplementation protocols are currently available [7,8]. This study evaluates zinc levels in a cross-sectional RDEB cohort and investigates their association with disease severity, skin complications, growth delay, anemia, inflammatory and infection burden, and psychological manifestations. By identifying patients at risk for zinc deficiency and elucidating its systemic effects, we aim to underscore the need for preventive and tailored interventions to improve clinical management and quality of life in patients with RDEB.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Patients, and Data Collection

This cross-sectional, observational, and non-interventional study has been described in detail elsewhere [3,29]. Briefly, from May to December 2021, all patients with a confirmed diagnosis of RDEB registered at the Spanish Reference Unit for EB (HULP) were considered for inclusion (n = 93). Clinical evaluations and sample collection were carried out during routine follow-up visits. Disease severity was assessed by a single dermatologist using the Epidermolysis Bullosa Disease Activity and Scarring Index (EBDASI), with established cut-offs applied [30] and disease-associated complications documented. Demographic information (Table S1), the percentage of body surface area (BSA) affected, the use of oral zinc supplementation (OZS), and the presence of active wound infection at the time of assessment were recorded. Patients were also asked about psychological symptoms, including depression, anxiety, and low mood. In addition, information was collected regarding previous culture-confirmed skin infections (history of cutaneous infection) and a history of hospitalizations due to severe infections (non-responsive to oral antibiotics or sepsis).

During the visit, anthropometric parameters were determined, and Z-scores for weight and height by age were calculated using contemporary Spanish reference charts [31] through the nutritional application provided by the Sociedad Española de Gastroenterología, Hepatología y Nutrición Pediátrica (Spanish Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition; SEGHNP; https://www.seghnp.org/nutricional/ accessed on 6 Jun 2022)). Peripheral blood was drawn only when the patient’s clinical condition allowed.

Routine biochemical and hematological parameters were analyzed in the Central Clinical Laboratory at HULP, applying standard reference ranges (Table S1). Interleukin-6 (IL6) levels were quantified using a commercial kit (Merck KGaA (Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain)) at the Hemostasis Laboratory according to established protocols as previously described [3], and an age- and sex-matched group of healthy controls served as the reference cohort. In this case, patient and control samples were processed in parallel to reduce variability. IL6 values exceeding the 95th percentile of the healthy control cohort distribution were considered abnormally high [3].

2.2. Zinc Quantification

Blood samples were obtained after overnight fasting, between 08:00 and 10:00 a.m., to minimize circadian variation in serum zinc and to avoid the effect of recent food intake. Samples with marked hemolysis (hemolysis index > 200 mg/dL hemoglobin) were excluded, as the release of intracellular zinc from erythrocytes can lead to overestimation of serum concentrations.

Serum zinc was measured by flame atomic absorption spectrometry using a Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 200 spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) with a deuterium background corrector and a zinc-specific hollow cathode lamp. Calibration curves were prepared weekly from certified 1000 ppm standards and accepted when the correlation coefficient was >0.99 and the variation compared with previous calibrations was <20%. Internal controls (Bio-Rad Liquid Assayed Multiqual (Alcobendas, Spain), levels 1–2) were included in each run, and external quality was monitored through participation in the SEQC trace elements program. All samples were analyzed in duplicate; results with a relative standard deviation (RSD) >3% were repeated, and dilutions were performed when concentrations exceeded the linear range. The method is accredited under the UNE-EN ISO 15189:2023 standard (Medical laboratories–Requirements for quality and competence. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023), within the scope of the laboratory’s accreditation.

2.3. Statistical Analysis and Visualization

Statistical analyses and data visualization were performed using Microsoft Excel 365, GraphPad Prism 8.0.2, SPSS v25.0, and Python 3.11.4 via the Data Analyst environment (OpenAI). Full details on all statistical procedures, software versions, and AI-assisted modeling and visualization are available in the Supplementary Methods.

3. Results

3.1. Zinc Status Is Related to Age Group and Disease Severity in RDEB

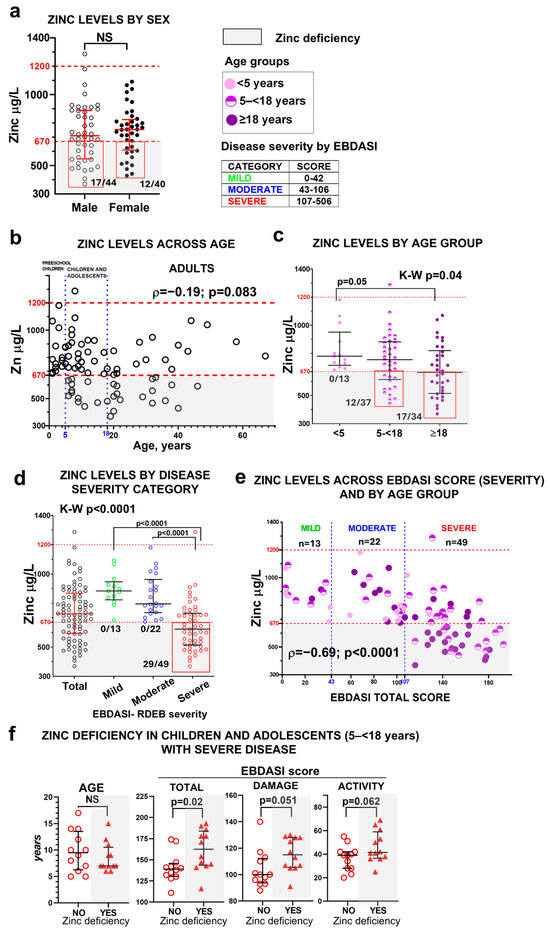

Zinc deficiency was identified in 29 of the 84 patients (34.5%). No significant differences were observed between sexes in either zinc levels or deficiency prevalence (Figure 1a). One patient with severe RDEB and no zinc supplementation showed zinc levels above the normal range, though no complications were associated with this finding. Zinc levels did not correlate with age as a continuous variable (Figure 1b) but differed by age group (Figure 1c). The risk of zinc deficiency increased with age (χ2 test, p = 0.003), affecting no preschool children (1–<5 years), 32% of children/adolescents (5–<18), and 47% of adults (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Zinc status in the RDEB cohort. Serum zinc levels are shown according to sex (a); across age as a continuous variable (b); by age group (preschool children <5 years, children and adolescents 5–<18 years, and adults ≥18 years) (c); by EBDASI severity categories (mild <43 points, moderate 43–106 points, and severe ≥107 points) (d). Panel (e) shows the relationship between serum zinc levels and the EBDASI score as a continuous variable, also stratified by age group. Statistical analyses include an unpaired t-test for panel (a), the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test for panels (c,d), and Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient (ρ) for panels (b,e). NS indicates non-significant results (p > 0.05). Error bars represent the median and interquartile range, and dashed lines denote the normal zinc reference range (red) and EBDASI severity thresholds (blue). Panel (f) shows the comparison of age (Mann–Whitney test) and EBDASI severity scores (unpaired t-test) in children and adolescents with severe disease, stratified by zinc status (with or without zinc deficiency, n = 12 per group) with error bars representing the median and interquartile range. Gray shading indicates zinc deficiency.

Zinc levels were significantly associated with disease severity, as defined by EBDASI score. All patients with zinc deficiency fell within the severe EBDASI category (≥107 points; Figure 1d, Table S2), and lower zinc concentrations correlated with higher EBDASI total scores (Figure 1e).

Given the developmental vulnerability of the children–adolescent group, when the progression of RDEB typically accelerates and the risk of complications and mortality increases, we focused on patients in this age range with severe disease. Although the age distribution was similar between zinc-deficient and non-deficient patients within this subgroup, those with zinc deficiency exhibited significantly higher EBDASI total scores as well as both activity and damage subscores (Figure 1f), indicating that zinc deficiency is associated with greater disease activity and cumulative tissue damage. This stage carries a higher physiological demand for zinc due to growth and tissue turnover. Zinc scarcity may therefore contribute to worsening disease burden and influence the natural course of RDEB.

OZS data are provided in the Supplementary Material, Figure S1. Overall, OZS often failed to match patients’ clinical needs, with many zinc-deficient patients not taking supplementation, and some supplemented individuals remaining deficient.

3.2. Zinc Deficiency and Its Clinical Consequences

3.2.1. Zinc Deficiency as a Risk Factor for Growth Impairment in RDEB Patients

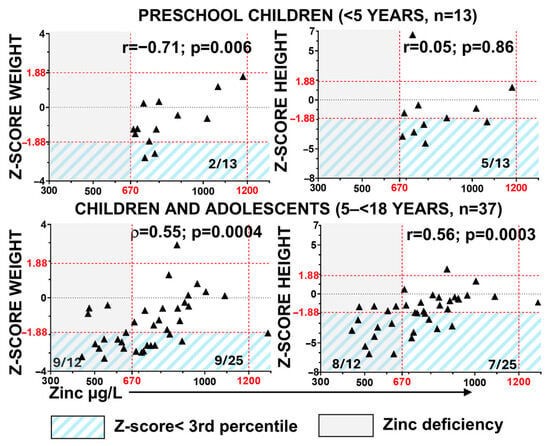

We assessed the correlation between zinc levels and Z-scores by age for weight (ponderal growth) and height (linear growth) (Figure 2). In preschool children, 15% (2/13) and 38% (5/13) had weight and height values below the 3rd percentile, respectively. However, only weight Z-scores exhibited a significant correlation with zinc levels in this group. In children and adolescents, the percentages of growth impairment increased in parallel with the rising prevalence of zinc deficiency (Figure 2), and a moderate positive correlation was observed between zinc levels and both height and weight Z-scores. Impaired ponderal growth occurred in 75% of zinc-deficient patients versus 36% of patients with normal blood zinc levels (χ2, p = 0.04), and stunted linear growth was observed in 67% versus 28%, respectively (χ2, p = 0.04). These findings suggest that zinc deficiency is associated with impaired growth in paediatric patients with RDEB.

Figure 2.

Association of zinc deficiency with growth impairment in RDEB. Correlation between serum zinc levels and anthropometric parameters was assessed using Z-scores for weight and height by age, calculated from contemporary Spanish reference charts [31]. Statistical analyses include Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient (ρ), with corresponding p-values. Red dashed lines indicate the normal zinc reference range (vertical) and the 3rd and 97th percentile thresholds for Z-scores (horizontal). Gray shading indicates zinc deficiency. Blue diagonal shading highlights patients with Z-scores below the 3rd percentile.

3.2.2. Zinc Deficiency Is Strongly Associated with Common Complications in RDEB

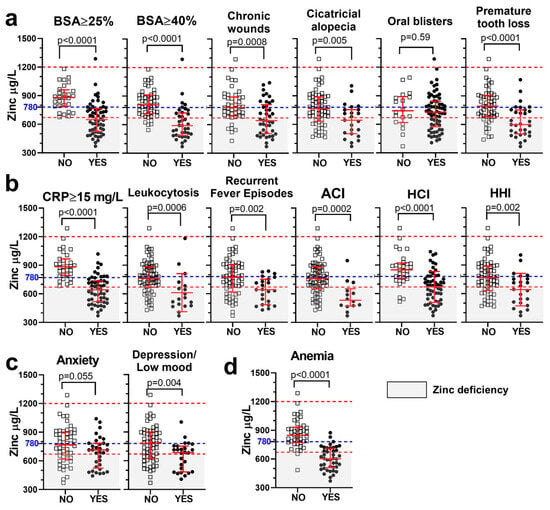

As shown in Figure 3, lower serum zinc levels, analyzed as a continuous variable, were found in patients with the most typical complications in RDEB. These included outcomes affecting the skin and oral mucosa (Figure 3a), complications related to inflammatory and infection burden (Figure 3b), as well as alterations in the psychological domain (Figure 3c) and anemia (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

Lower serum zinc levels in patients presenting with the most frequent complications in RDEB. Zinc levels, analyzed as a continuous variable (µg/L), are compared between patients with (“Yes”, open squares) or without (“No”, solid circles) specific clinical outcomes: cutaneous and oral complications (a), inflammatory and infectious burden (b), psychological symptoms (c), and anemia (d). Statistical analysis (p-value) was performed using an unpaired t test. Dashed lines indicate the normal zinc range (red) and the proposed threshold for preventive supplementation (780 µg/L; blue). %BSA = percentage of body surface area affected; CRP = C-reactive protein; ACI = active cutaneous infection; HCI = history of cutaneous infection; HHI = history of hospitalization due to serious infection (nonresponsive to oral antibiotics or sepsis). Gray shading indicates zinc deficiency.

Statistically significant associations with zinc deficiency, analyzed as a binary variable (<670 µg/L cutoff), were strongest in the domains of cutaneous and mucosal involvement, inflammatory and infectious burden, and anemia, indicating that these complications were more prevalent among patients with zinc deficiency. In contrast, psychological complications did not show significant associations in the binary analysis (Table 1). Notably, higher proportions of patients with extensive skin involvement (BSA ≥ 25% or ≥40%) and chronic wounds were found among those with zinc deficiency (Table 1).

Table 1.

Association of clinical outcomes with zinc deficiency. Predictive value of zinc deficiency, as a binary variable (deficient, no deficient) with cutoff 670 µg/L, for most common RDEB complications.

Permanent complications such as cicatricial alopecia and premature tooth loss were also more prevalent in the zinc-deficient group, supporting the long-term consequences of suboptimal zinc status. In contrast, oral blisters, despite their frequency in RDEB, were not significantly associated with zinc levels (Figure 3a, Table 1).

Supporting the known role of zinc in immune function, lower zinc levels were associated with an increased proportion of patients with moderate-to-high levels of CRP and an increased infection burden, evidenced by higher rates of leukocytosis, active cutaneous infection, history of cutaneous infection, and history of hospitalization due to severe infection (Figure 3b, Table 1).

The strongest associations with zinc deficiency were observed for anemia (odds ratio (OR) = 36, p < 0.0001), CRP ≥ 15 mg/L (OR = ∞, p < 0.0001), extensive skin involvement (BSA ≥ 25%: OR = ∞; BSA ≥ 40%: OR = 15; both p < 0.0001), and chronic wounds (OR = 10, p < 0.0001). The highest Youden’s J indices were observed for anemia (J = 0.60), CRP ≥ 15 (J = 0.55), and BSA ≥ 40% (J = 0.54), indicating moderate diagnostic utility (Table 1).

3.3. Zinc Threshold for Preventive Risk Stratification in RDEB

Despite these strong associations, the sensitivity of the current zinc deficiency cutoff according to the laboratory’s reference interval (670 µg/L) remains below 70% for most outcomes (Table 1), limiting its effectiveness as a clinically meaningful preventive supplementation threshold and increasing the risk that vulnerable RDEB patients may go unrecognized. This pattern is consistent with zinc’s classification as a Type 2 nutrient, in which clinical manifestations such as impaired growth, immune dysfunction, and delayed wound healing often precede measurable declines in circulating levels [32].

To improve risk detection and guide preventive intervention, we calculated zinc thresholds corresponding to 80% sensitivity for complications that not only showed strong statistical associations with zinc status but also represent early drivers of morbidity in RDEB, particularly extensive skin involvement, systemic inflammation/infection-related outcomes, and anemia. Analyses were performed in the overall cohort and stratified by two age groups (children and adults) to capture possible differences in physiological requirements and disease presentation.

Across complications, the zinc levels required to achieve the sensitivity target ranged from 728 to 790 µg/L, with some variation by age group (Table S4). Among these, a fixed threshold of 780 µg/L emerged as a consistent and clinically practical option. It provided high sensitivity (≥80%) and moderate-to-high specificity for the key systemic complications mentioned above. Additionally, negative predictive values were consistently high at this threshold, supporting its use as a reliable screening tool to rule out clinical risk (Table S5).

Altogether, a threshold of 780 µg/L shows strong diagnostic performance for identifying patients at risk of systemic complications in RDEB, while prospective studies are required to determine its role in guiding preventive zinc supplementation.

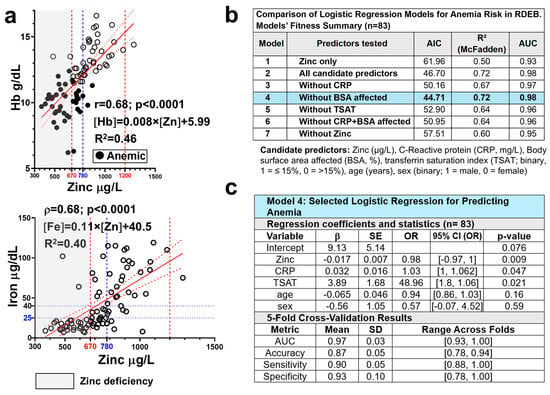

3.4. Zinc Levels as a Risk Predictor of Anemia in RDEB

We previously reported that anemia is a prevalent and multifactorial complication in this cohort, affecting 50% of patients [29]. The main aetiopathogenic factors identified as contributing to anemia in RDEB include the extent of skin involvement, systemic inflammation, and both functional and true iron deficiency [29,33,34,35]. In addition to these factors, we examined whether zinc deficiency contributes to anemia risk in this cohort. Hemoglobin and zinc levels showed a strong correlation (Figure 4a), and patients with anemia exhibited significantly lower zinc levels compared to those without anemia (Figure 3d). Notably, 93% (27/29) of patients with zinc deficiency had anemia, representing a threefold higher prevalence compared with patients with zinc levels within the normal range (Table 1). Hypoferremia and zinc deficiency coexisted in many patients in this cohort, although hypoferremia was more common (Figure 4a). A univariate logistic regression model including serum zinc levels accounted for substantial variability in anemia risk (pseudo-R2 = 0.5) and showed a high discriminative capacity (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) = 0.93), highlighting the strength of this association (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Zinc levels as a predictor of anemia risk in RDEB. (a) Correlation of serum zinc levels (µg/L) with hemoglobin (Hb, g/dL; n = 84) and serum iron (µg/dL; n = 83) in patients with RDEB. Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient (ρ) and corresponding p-values are shown; linear regression lines (solid red lines) with 95% confidence intervals (dotted red lines) are displayed. Vertical dashed lines indicate the normal zinc range (in red) and the proposed threshold for preventive supplementation (780 µg/L; blue) Gray shading indicates zinc deficiency. (b) Comparison of logistic regression models with different predictor sets and (c) summary of the final selected model (Model 4), including 5-fold cross-validation results. Blue shading highlights the selected model. CRP = C-reactive protein; BSA = Body surface area; TSAT = transferrin saturation; AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; R2 (McFadden) = pseudo-R2; AUC = area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. β = represent log-odds from the logistic regression model predicting anemia risk (1 = anemic, 0 = non-anemic); SE = Standard error of the β coefficient; OR = odds ratio (eβ); p-value = statistical significance of each predictor; 95% CI (OR): confidence interval for OR estimates, reported as [lower, upper] SD = Standard deviation.

To determine whether zinc levels remain an independent predictor of anemia risk when accounting for other relevant clinical variables, namely inflammation, extent of skin involvement, and iron bioavailability, multifactorial logistic regression models were constructed and compared. Models included zinc, CRP, %BSA affected, TSAT ≤ 15%, age, and sex, and were tested iteratively by removing predictors (Figure 4b, Table S6). Interaction terms (Zinc × CRP and Zinc × TSAT) were also evaluated and found to be non-significant (p = 0.83 and p = 0.91, respectively), suggesting that the effect of zinc was not dependent on inflammation or iron status. Accordingly, they were excluded from the tested models for clarity and parsimony in the model including all candidate predictors (Model 2, Table S6), zinc levels remained significantly associated with anemia risk (p = 0.012), and TSAT ≤ 15% strongly predicted anemia (p = 0.014), with patients above this threshold being approximately 49 times more likely to be non-anemic. In contrast, CRP showed only a marginal association (p = 0.058), and %BSA affected was not significant in this or any other model tested (Table S6). Excluding %BSA (Model 4) improved fit (lower Akaike information criterion, AIC) while preserving its performance (pseudo-R2 = 0.72; AUC = 0.98) (Figure 4b). Excluding zinc (Model 7) reversed the intercept, increased CRP’s coefficient, and worsened model performance (lower AUC and higher AIC), highlighting zinc’s relevant role in both prediction and model stability (Figure 4b).

Mediation analysis (Baron & Kenny method and Sobel test; Table S7) further supported that reduced zinc availability partially mediates the negative effects of inflammation and skin damage on erythropoiesis and anemia risk.

Model validation (5-fold cross-validation) confirmed robustness and generalizability, with cross-validated AUC of 0.97 and mean predictive accuracy exceeding 85% across folds. These findings establish blood zinc concentration as an independent and consistent predictor of anemia risk in RDEB, adding predictive value beyond inflammation and iron availability markers. Specifically, each 1 µg/L increase in zinc was associated with an approximately ≈ 2% higher likelihood of being non-anemic.

To illustrate the clinical relevance of this association, we estimated the predicted anemia risk in patients with similar inflammatory and iron-deficient profiles, varying only in their zinc levels. For a 20-year-old female with CRP = 15 mg/L and TSAT ≤ 15%—A high-risk profile in this cohort—the predicted probability of anemia was approximately 69% when serum zinc was 670 µg/L. In contrast, if zinc was 780 µg/L, the predicted risk dropped to 26%. This corresponds to a ~43% absolute risk reduction associated with higher zinc levels, underscoring the proposed independent protective effect of zinc and supporting the clinical relevance of the 780 µg/L threshold as a potential target for intervention.

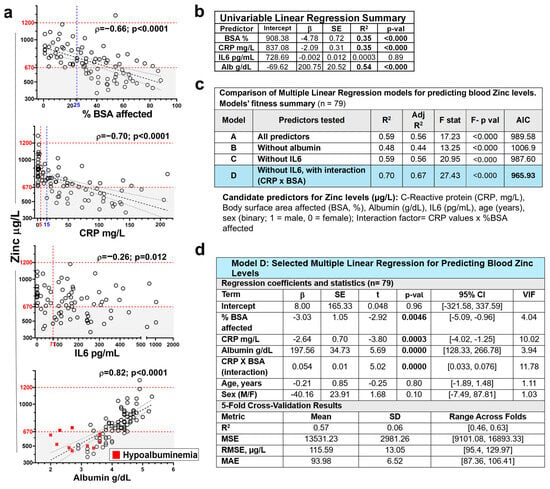

3.5. Analysis of Factors Determining Blood Zinc Levels

To identify clinical and biochemical predictors of zinc levels in RDEB, we explored variables selected based on their pathophysiological likelihood and observed correlation in the cohort (Figure 5a): the extent of skin damage (percentage BSA affected), inflammatory markers (CRP, IL6), and the main circulating zinc carrier and negative acute-phase protein (serum albumin). In univariate linear regression, zinc levels showed moderate negative associations with the percentage of BSA affected and CRP levels, and a strong positive association with serum albumin, while IL6 did not reach statistical significance (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Factors influencing blood zinc levels in RDEB. (a) Scatterplots showing the association between blood zinc levels (µg/L) and potential predictors, including percentage of body surface area affected (BSA; %, n = 84), serum C-reactive protein (CRP; mg/L, n = 84), interleukin-6 (IL6; pg/mL, n = 79), and albumin (g/dL, n = 84), with fitted linear regression lines (dashed black) and 95% confidence intervals (dotted). Horizontal dashed lines indicate the normal zinc reference range. Gray shading indicates zinc deficiency. Dashed vertical red lines indicate the normal range for CRP (5 mg/L) and the 95th percentile of healthy controls used as the cut-off for IL-6 (77 pg/mL; [3]). (b) Statistical output of the corresponding univariable linear regression models predicting blood zinc levels. (c) Comparison of logistic regression models including different predictor sets (with or without albumin, IL6 and CRP × BSA interaction; n = 79). (d) Summary of the final selected model (Model D), including 5-fold cross-validation results. Blue shading highlights the selected model. β = unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = standard error of the regression coefficient β; p-val= p-value for testing β ≠ 0; R2 = coefficient of determination; Adj R2 = Adjusted R2; F stat = Fisher’s F-test result; F- p val = Fisher’s F-test p value; AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; t = T-statistic (β/SE); 95% CI = confidence interval; VIF = Variance Inflation Factors; MSE = mean squared error; RMSE = root mean squared error in the original units of zinc. MAE = mean absolute error; SD = standard deviation.

The comparative analysis of the performance of candidate predictors in multivariate models, including or not including albumin and IL6, and adjusted for age and sex, confirmed albumin as the strongest predictor of zinc levels, while discarding the independent relevance of IL6 (Figure 5c,d and Table S8). In addition, as suggested by exploratory data analysis, the inclusion of a CRP × BSA interaction term significantly improved the model ‘s fit (adjusted R2 = 0.70; ΔAIC = −21.7) (Figure 5c). Notably, the interaction coefficient was positive (β = 0.05), indicating that although both inflammation and skin involvement were independently associated with lower zinc levels, their combined effect became less than additive at extreme values.

The selected model (Model D; Figure 5d) generalizability along cohort subgroups, was assessed by 5-fold cross validation, achieving a mean R2 of 0.57 and root mean squared error (RMSE) of 115.59 µg/L across folds.

Finaly, mediation analysis (Baron & Kenny approach and Sobel test) confirmed that albumin significantly mediated the effects of CRP and BSA on zinc (Table S9), jointly explaining 72% of the albumin variance. These findings support a model in which skin damage and inflammation affect zinc levels primarily through their impact on serum albumin but may also exert a direct effect.

4. Discussion

This cross-sectional study characterizes zinc status in a representative cohort of patients with RDEB, a devastating congenital and chronic genodermatosis. Prior to this study, the clinical relevance of zinc in RDEB had largely been inferred from indirect evidence, extrapolated from its well-established roles in epithelial repair, immune function, and hematopoiesis, in the absence of direct, disease-specific investigations. Evidence from the analysis of this cohort demonstrates a clear association between zinc deficiency, disease severity, and a wide spectrum of complications, including chronic wounds, inflammation, infection burden, and growth impairment, many of which have a direct impact on quality of life and prognosis. Moreover, zinc levels emerged as the strongest predictor of anemia risk in RDEB patients.

4.1. Determinants of Zinc Status in RDEB

Zinc deficiency is common in chronic inflammatory and malnourished states, particularly in children, but it remains frequently underdiagnosed [36,37]. Zinc deficiency was observed in one-third of the total cohort and in two-thirds of patients with severe EBDASI scores, a proportion lower than previously reported in other cohorts with diverse demographic and clinical characteristics [27,28,38]. IL6 was only weakly associated with serum zinc levels, whereas CRP and extent of skin involvement (BSA affected) were identified as relevant and additive factors determining zinc deficiency. These associations were largely mediated by serum albumin, the main zinc carrier in circulation and the strongest independent predictor of its levels in RDEB. Albumin decline may precede zinc scarcity, as it reflects protein loss from wounds and inflammation-driven hepatic downregulation [28].

Zinc deficiency itself may further impair albumin synthesis [39,40], creating a vicious cycle that undermines systemic zinc transport and bioavailability. Consistently, albumin status could also influence the response to OZS. Because serum albumin reflects the overall protein–energy status, zinc supplementation should be integrated with comprehensive nutritional intervention, as has been previously suggested [8,41].

4.2. Relationship Between Zinc Deficiency and Skin Involvement in RDEB

Zinc’s role in wound healing is well established [42,43,44]. Topical formulations, such as zinc oxide, widely used in dermatology for exudative wounds and chronic ulcers, provide anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and re-epithelialization benefits even in normozincemic individuals [42,44,45]. Such mechanisms are particularly relevant in RDEB, where effective management of chronic wounds remains a central therapeutic challenge. However, although zinc-containing dressings are listed among optional products in EB resources, evidence for their use in RDEB is lacking and their clinical application has not been formally documented. Extensive application of zinc-containing dressings could increase systemic zinc absorption [46] and potentially result in toxicity [47]; their use should therefore remain localized and be carefully monitored.

Chronic wounds may be both a cause and a consequence of zinc deficiency. In our cohort, zinc deficiency was strongly associated with extensive skin damage: patients with wounds affecting ≥25% of their body surface had a markedly increased risk of zinc deficiency. Conversely, zinc-deficient individuals more frequently exhibited delayed healing and severe skin involvement (e.g., BSA ≥ 40%), suggesting a self-perpetuating loop of zinc loss and impaired repair.

4.3. Systemic Consequences of Zinc Deficiency: Growth Impairment, Immune Dysregulation, and Anemia in RDEB

In children with RDEB, we observed a correlation between serum zinc levels and weight- and height-for-age Z-scores from the age of five onward, an association previously reported for weight by Reimer et al. [28] This supports a link between zinc deficiency and growth retardation, although stunting typically begins earlier than the onset of measurable zinc depletion [48,49]. Given the multifactorial nature of growth impairment in RDEB, including inflammation and nutritional compromise, both intermingled with zinc status, it is difficult to establish a direct causal pathway. Nonetheless, zinc deficiency is known to impair the synthesis and signaling of thyroid hormones [50], androgens [51], and growth hormone [52,53], and zinc supplementation has been shown to improve growth and increase insulin-like growth factor 1 levels in pediatric populations [54,55,56].

Zinc is essential for immune function and inflammatory balance, a role that is particularly relevant in RDEB, where persistent inflammation and increased vulnerability to infections are major drivers of morbidity [19,21]. Zinc deficiency compromises the mechanisms that restrain NF-κB signaling, thereby enhancing proinflammatory cytokine production [57,58,59]. In RDEB, where damage-associated molecular patterns such as HMGB1 can activate NF-κB [60,61], zinc scarcity may further amplify these pathways, sustaining local and systemic inflammation. In parallel, zinc is essential for effective innate and adaptive immune responses, including neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, thymic integrity, and B-cell differentiation [19]. Its deficiency impairs antimicrobial defense and increases susceptibility to recurrent infections and sepsis [19,21], major contributors to morbidity and mortality in RDEB [4,5,62]. Prophylactic zinc supplementation has been shown to reduce infection incidence in other settings, whereas its effectiveness appears limited once infection is established [63]. Whether similar benefits apply to RDEB requires prospective evaluation. In our cohort, zinc-deficient patients with severe disease were more likely to exhibit higher inflammatory markers and clinical signs of immune dysfunction, including leukocytosis, recurrent febrile episodes, active skin infections, and a history of serious infections. This strengthens the rationale for considering zinc status as a key modulator of inflammation and a determinant of immune competence in RDEB.

Anemia, a highly prevalent and multifactorial complication in RDEB [29,33,34,35], has been associated with zinc deficiency in different contexts [64,65,66,67]. Our study extends this evidence by demonstrating that zinc deficiency is also a significant contributor to anemia in RDEB. Zinc supports erythropoiesis through several mechanisms: it acts as a cofactor for enzymes involved in heme synthesis and oxidative stress protection and serves as a cofactor for transcription factors such as GATA-1 and FOG-1, which mediate erythropoietin (EPO) signalling and are indispensable for early erythroid commitment [68,69]. Zinc also influences the production and activity of insulin-like growth factor 1 and the growth hormone pathway, which synergize with EPO during erythropoiesis [54,69,70]. Consistent with these mechanisms, logistic regression analysis identified low serum zinc as an independent predictor of anemia risk in RDEB, with an effect size comparable to CRP and TSAT, even after adjustment for inflammation and iron status. This role is further supported by the interplay between zinc and iron metabolism, particularly relevant in RDEB, where coexisting deficiencies may exacerbate anemia and reduce response to standard treatments. Zinc repletion has been shown to improve iron mobilization and hemoglobin synthesis by upregulating the expression of key transporters such as divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) and ferroportin [69,71,72]. In chronic inflammatory conditions like chronic kidney disease, zinc supplementation enhances erythropoietic responses even in patients refractory to EPO therapy [67,73]. Accordingly, these findings support the biological plausibility of zinc deficiency as a relevant factor associated with anemia in RDEB, given its established roles in iron mobilization, inflammatory regulation, and erythropoiesis. Taken together, they provide a rationale for monitoring zinc status and correcting deficiency as part of anemia management, pending confirmation in interventional studies.

4.4. Rationale for Guiding Zinc Preventive Supplementation in RDEB

Our data show that zinc deficiency often emerges during childhood in patients with RDEB, a period marked by increased physiological demands due to growth and disease progression. Although zinc supplementation is widely recommended for patients with chronic wounds, inflammation, or growth impairment [22], specific criteria to initiate preventive therapy (such as thresholds for skin involvement, severity scores, CRP levels, or age) have not been defined, and dosing guidelines tailored to RDEB are lacking. Regular monitoring of serum zinc is advised in RDEB to guide supplementation, and current recommendations are largely extrapolated from general pediatric and adult practice [7,8]. Consistent with zinc’s classification as a Type 2 nutrient [32,48], circulating deficiency typically becomes evident once functional consequences are evident, supporting the need for clinically anchored preventive thresholds in RDEB.

The comparison with burn patients provides valuable clinical insight. Both conditions involve sustained metabolic demands, persistent inflammation, and significant exudative losses, all contributing to macro- and micronutrients depletion, including zinc [74,75]. In hospitalized burn patients, empirical high-dose zinc supplementation, often enteral or intravenous, is routinely recommended for 2–3 weeks, irrespective of baseline serum levels, improving wound healing and reducing infection rates and mortality [74,75,76]. While RDEB is chronic rather than acute, its metabolic profile (oxidative stress, immune dysregulation, and hypercatabolism) is strikingly similar. These parallels reinforce the rationale for a more proactive and sustained approach to zinc repletion in RDEB, aimed not only at restoring serum levels but also at counteracting ongoing losses and supporting systemic resilience.

The proposed threshold of 780 µg/L identified in this study achieved ≥80% sensitivity for major clinical complications, suggesting that it may be clinically more meaningful than the conventional cutoff for zinc deficiency. While this threshold could be considered conservative when compared with clinical practice in burn care, the chronic nature of RDEB requires sustained long-term management. Although OZS has a favorable safety profile, caution is warranted with prolonged high-dose use due to risks such as copper depletion [17,71,77]. In addition, concurrent iron supplementation may reduce the effectiveness of both micronutrients, given their competition for intestinal absorption [71,77]. Other common dietary components, including calcium, fiber, and phytates, often present in nutritional shakes prescribed to RDEB patients, can attenuate zinc absorption [71,77]. This reinforces the importance of nutritional expertise in guiding dose scheduling and timing of supplementation to maximize efficacy.

4.5. Limitations of This Study

The cross-sectional and single-center design of this study limits causal inference and generalizability. Residual confounding from variables that are difficult to quantify in this setting (such as dietary intake or socioeconomic factors) cannot be fully excluded. Prospective and interventional studies are therefore needed to confirm the value of the proposed preventive threshold (780 µg/L) and to determine the most effective zinc repletion strategies for improving clinical outcomes in RDEB.

5. Conclusions

This study provides the first disease-specific characterization of zinc status in RDEB, revealing strong associations with disease severity, anemia, impaired growth, chronic wounds, inflammation, and compromised immune competence. Zinc deficiency emerges as a clinically relevant and modifiable factor associated with complication burden, supporting the rationale for systematic monitoring and correction of deficiency as part of comprehensive supportive care and complication management in RDEB. As this study is cross-sectional, no causal or interventional conclusions can be drawn, and randomized controlled trials are required to determine whether zinc supplementation improves clinical outcomes and to define optimal repletion strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu18020232/s1. Supplementary Methods (Statistical analysis, Python-based analyses), Table S1 (Standard laboratory reference ranges), Supplementary Results (Oral Zinc Supplementation across age and severity; Figure S1), and Tables S2–S9 (expanded results and model details). Reference [78] are cited in the supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.E. and R.S.; methodology, L.Q.-C., R.M., M.J.E. and R.S.; validation, L.Q.-C., R.M., N.B., M.M.-L., M.G.C. and A.B.; formal analysis, L.Q.-C., P.Z., M.d.R., Á.V., M.J.E. and R.S.; investigation, L.Q.-C., R.M., S.S.-R., N.B.,., M.M.-L., M.G.C., A.B., S.H.-G., C.L., A.V., L.M.F.-S. and R.d.L.; resources, L.Q.-C., R.M., N.B., A.B. and R.d.L.; data curation, L.Q.-C., M.M.-L., M.G.C., A.B., N.B., P.Z., M.J.E. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Q.-C., M.J.E. and R.S.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, L.Q.-C., M.J.E. and R.S.; supervision, M.J.E. and R.S.; project administration, M.J.E. and R.S.; funding acquisition, R.d.L., M.d.R., Á.V. and M.J.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the HULP-IdiPaz Dermatology Service and by FIBHULP (EC_5215; I4V-MC-JAIP); grants PID2020-119792RB-I00 (funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) and PID2021-123068OB-I00 (funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF A way of making Europe”); and projects RICORS-TERAV RD21/0017/0033 and RD21/0017/0010 (funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, co-financed by the European Union through NextGenerationEU). MJE was the recipient of a contract funded by DEBRA Austria, co-funded by DEBRA Sweden and EB-LOPPET and supported by EB Research Network (León-1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Hospital Universitario La Paz (HULP; Code: PI-4690, 11 May 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians prior to enrollment, covering participation in the study and the publication of results in scientific journals.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting this study are available to qualified academic researchers upon substantiated request to corresponding authors, provided the request aligns with the objectives specified in the participants’ consent agreements. Any data release will adhere to privacy protection protocols, such as deidentification, and will comply with applicable legal requirements.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our profound gratitude to the patients and their families for their participation in this study. We further extend our deepest appreciation to the patient advocacy groups DEBRA-España and Berritxuak for their support and collaboration. During the preparation of this work, some stages of the statistical analyses and document generation were conducted using the Data Analyst environment within ChatGPT (OpenAI Plus, models available during June-September 2025), which provides access to Python (version 3.11.4) and scientific libraries (pandas, statsmodels, numpy, scipy). All analyses were subsequently reviewed and re-run independently by the authors to ensure consistency and accurate variable coding. The authors take full responsibility for the study design, data analysis, interpretation of results, and final reporting. AI assistance was used solely as a computational and editorial support tool under the direct supervision of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| AUC | Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| BSA | Body surface area |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| EBDASI | Epidermolysis bullosa disease activity and severity index |

| IL6 | Interleukin-6 |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| OZS | Oral zinc supplementation |

| RDEB | Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa |

References

- Bardhan, A.; Bruckner-Tuderman, L.; Chapple, I.L.C.; Fine, J.-D.; Harper, N.; Has, C.; Magin, T.M.; Marinkovich, M.P.; Marshall, J.F.; McGrath, J.A.; et al. Epidermolysis bullosa. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakioulaki, M.; Kwarteng, N.A.; Nikolakopoulou, A.; Yang, H.; Hess, M.; Binder, H.; Eyerich, K.; Has, C. Tissue and systemic inflammation in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Castanedo, L.; Sanchez-Ramon, S.; Maseda, R.; Illera, N.; Perez-Conde, I.; Molero-Luis, M.; Butta, N.; Arias-Salgado, E.G.; Monzon-Manzano, E.; Zuluaga, P.; et al. Unveiling the value of C-reactive protein as a severity biomarker and the IL4/IL13 pathway as a therapeutic target in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: A multiparametric cross-sectional study. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, e15146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellerio, J.E. Infection and colonization in epidermolysis bullosa. Dermatol. Clin. 2010, 28, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Espinosa, L.; del Rosal, T.; Quintana, L.; Maseda, R.; Grasa, C.; Falces-Romero, I.; Menéndez-Suso, J.; Pérez-Conde, I.; Méndez-Echevarría, A.; Aracil-Santos, F.J.; et al. Bloodstream infection in children with epidermolysis bullosa. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2023, 42, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popp, C.; Miller, W.; Eide, C.; Tolar, J.; McGrath, J.A.; Ebens, C.L. Beyond the Surface: A Narrative Review Examining the Systemic Impacts of Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 144, 1943–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hachem, M.; Diociaiuti, A.; Bonamonte, D.; Brena, M.; Lospalluti, L.; Magnoni, C.; Neri, I.; Peris, K.; Tadini, G.; Zambruno, G. Taking care of patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa from birth to adulthood: A multidisciplinary Italian Delphi consensus. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salera, S.; Tadini, G.; Rossetti, D.; Grassi, F.S.; Marchisio, P.; Agostoni, C.; Giavoli, C.; Rodari, G.; Guez, S. A nutrition-based approach to epidermolysis bullosa: Causes, assessments, requirements and management. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togo, C.C.G.; Zidorio, A.P.C.; Gonçalves, V.S.S.; Hubbard, L.; de Carvalho, K.M.B.; Dutra, E.S. Quality of life in people with epidermolysis bullosa: A systematic review. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2020, 29, 1731–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellerio, J.E.; Pillay, E.I.; Sollesta, K.; Thiel, K.E.; Zimmerman, G.; McGrath, J.A.; Martinez, A.E.; Jeffs, E. Milestone events in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: Findings of the PEBLES study. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2025, 50, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bageta, M.; Yerlett, N.; McGrath, J.; Mellerio, J.; Petrof, G.; Martinez, A. The Natural History of Severe Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa–4 Phases Which may Help Determine Different Therapeutic Approaches. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 2, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa, L.; Enzo, E.; Palamenghi, M.; Sercia, L.; De Luca, M. Stairways to Advanced Therapies for Epidermolysis Bullosa. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, M.J.; Panda, S.; Reineke, T.M.; Tolar, J.; Nyström, A. Progress in skin gene therapy: From the inside and out. Mol. Ther. 2025, 33, 2065–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A. Prademagene Zamikeracel: First Approval. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2025, 29, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Riaz, R.; Ashraf, S.; Akilimali, A. Revolutionary breakthrough: FDA approves Vyjuvek, the first topical gene therapy for dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 6298–6301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.K.; Malek, A.J.; Islam, K.N.; Prejean, R.; Lipner, S.R.; Wu, J.J.; Haas, C.J. VYJUVEK for dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: Ethical dilemmas in access and pricing. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2025, 94, E15–E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, L.I.; Ferrao, K.; Mehta, K.J. Role of zinc in health and disease. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasapis, C.T.; Ntoupa, P.A.; Spiliopoulou, C.A.; Stefanidou, M.E. Recent aspects of the effects of zinc on human health. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 1443–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammoh, N.Z.; Rink, L. Zinc in Infection and Inflammation. Nutrients 2017, 9, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.I.; Sarmento-Ribeiro, A.B.; Gonçalves, A.C. Zinc: From Biological Functions to Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, I.; Maywald, M.; Rink, L. Zinc as a Gatekeeper of Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, L. Nutrition for children with epidermolysis bullosa. Dermatol. Clin. 2010, 28, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.Y.; Marinkovich, M.P.; Lucas, E.; Gorell, E.; Chiou, A.; Lu, Y.; Gillon, J.; Patel, D.; Rudin, D. A systematic literature review of the disease burden in patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins Freitas, G.; Claure, L.H.; de Andrade, F.A.; Purim, K.S.M. The impact of epidermolysis bullosa on quality of life and mental health. Discov. Ment. Health 2025, 5, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, Y.; Kinoshita, M.; Shimada, S.; Kawamura, T. Zinc in Keratinocytes and Langerhans Cells: Relevance to the Epidermal Homeostasis. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 5404093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, N.F. Overview of zinc absorption and excretion in the human gastrointestinal tract. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1374S–1377S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingen-Housz-Oro, S.; Blanchet-Bardon, C.; Vrillat, M.; Dubertret, L. Vitamin and trace metal levels in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2004, 18, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laimer, M. Growth profile and anaemia in children with epidermolysis bullosa. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 1327–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Castanedo, L.; Maseda, R.; Pérez-Conde, I.; Butta, N.; Monzón-Manzano, E.; Acuña-Butta, P.; Crespo, M.G.; Buño-Soto, A.; Jiménez, E.; Valencia, J.; et al. Interplay between iron metabolism, inflammation, and EPO-ERFE-hepcidin axis in RDEB-associated chronic anemia. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 2321–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, C.L.; Gibson, M.; Kern, J.S.; Martin, L.K.; Robertson, S.J.; Daniel, B.S.; Su, J.C.; Murrell, O.G.C.; Feng, G.; Murrell, D.F. A comparison study of outcome measures for epidermolysis bullosa: Epidermolysis Bullosa Disease Activity and Scarring Index (EBDASI) and the Instrument for Scoring Clinical Outcomes of Research for Epidermolysis Bullosa (iscorEB). JAAD Int. 2021, 2, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrascosa, A.; Mesa, J. Barcelona Longitudinal Growth Study 1995–2017. Endocrinol. Diabetes Y Nutr. 2018, 65, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentice, A.M.; Gershwin, M.E.; Schaible, U.E.; Keusch, G.T.; Victora, C.G.; Gordon, J.I. New challenges in studying nutrition-disease interactions in the developing world. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 1322–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarango, C.; Quinn, C.T.; Augsburger, B.; Lucky, A.W. Iron status and burden of anemia in children with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2023, 40, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, A.; Hess, M.; Schwieger-Briel, A.; Kiritsi, D.; Schauer, F.; Schumann, H.; Bruckner-Tuderman, L.; Has, C. Natural history of growth and anaemia in children with epidermolysis bullosa: A retrospective cohort study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 1437–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liy-Wong, C.; Tarango, C.; Pope, E.; Coates, T.; Bruckner, A.L.; Feinstein, J.A.; Schwieger-Briel, A.; Hubbard, L.D.; Jane, C.; Torres-Pradilla, M.; et al. Consensus guidelines for diagnosis and management of anemia in epidermolysis bullosa. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2023, 18, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.H.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.J. Hair Zinc Level Analysis and Correlative Micronutrients in Children Presenting with Malnutrition and Poor Growth. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2016, 19, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, N.F.; Miller, L.V.; Hambidge, K.M. Zinc deficiency in infants and children: A review of its complex and synergistic interactions. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 2014, 34, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, J.-D.; Tamura, T.; Johnson, L. Blood Vitamin and Trace Metal Levels in Epidermolysis Bullosa. Arch. Dermatol. 1989, 125, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, K. Zinc and protein metabolism in chronic liver diseases. Nutr. Res. 2020, 74, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiru, S.; Kugiyama, Y.; Suehiro, T.; Motoyoshi, Y.; Saeki, A.; Nagaoka, S.; Yamasaki, K.; Komori, A.; Yatsuhashi, H. Zinc supplementation with polaprezinc was associated with improvements in albumin, prothrombin time activity, and hemoglobin in chronic liver disease. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2024, 74, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, L. Epidermolysis Bullosa. In Clinical Paediatric Dietetics; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 482–496. [Google Scholar]

- Lansdown, A.B.G.; Mirastschijski, U.; Stubbs, N.; Scanlon, E.; Agren, M.S. Zinc in wound healing: Theoretical, experimental, and clinical aspects. Wound Repair Regen. 2007, 15, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-H.; Sermersheim, M.; Li, H.; Lee, P.; Steinberg, S.; Ma, J. Zinc in Wound Healing Modulation. Nutrients 2017, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, S.; Sood, A.; Garnick, M.S. Zinc and Wound Healing: A Review of Zinc Physiology and Clinical Applications. Wounds A Compend. Clin. Res. Pract. 2017, 29, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M.; Mahajan, V.K.; Mehta, K.S.; Chauhan, P.S. Zinc therapy in dermatology: A review. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2014, 2014, 709152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agren, M.S. Percutaneous absorption of zinc from zinc oxide applied topically to intact skin in man. Dermatologica 1990, 180, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoofs, H.; Schmit, J.; Rink, L. Zinc Toxicity: Understanding the Limits. Molecules 2024, 29, 3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.C. Zinc: An essential but elusive nutrient. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 679s–684s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, J.C.; Brown, K.H.; Gibson, R.S.; Krebs, N.F.; Lowe, N.M.; Siekmann, J.H.; Raiten, D.J. Biomarkers of Nutrition for Development (BOND)-Zinc Review. J. Nutr. 2015, 146, 858s–885s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severo, J.S.; Morais, J.B.S.; de Freitas, T.E.C.; Andrade, A.L.P.; Feitosa, M.M.; Fontenelle, L.C.; de Oliveira, A.R.S.; Cruz, K.J.C.; do Nascimento Marreiro, D. The Role of Zinc in Thyroid Hormones Metabolism. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2019, 89, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín de Jesús, S.; Vigueras-Villaseñor, R.M.; Cortés-Barberena, E.; Hernández-Rodriguez, J.; Montes, S.; Arrieta-Cruz, I.; Pérez-Aguirre, S.G.; Bonilla-Jaime, H.; Limón-Morales, O.; Arteaga-Silva, M. Zinc and Its Impact on the Function of the Testicle and Epididymis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Hui, J.; Luo, G.; Hong, P.; Li, L.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Lan, H. Zinc ions increase GH signaling ability through regulation of available plasma membrane-localized GHR. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 23388–23397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, B.C.; Mulkerrin, M.G.; Wells, J.A. Dimerization of human growth hormone by zinc. Science 1991, 253, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, C.X.; Vale, S.H.L.; Dantas, M.M.G.; Maia, A.A.; Franca, M.C.; Marchini, J.S.; Leite, L.D.; Brandao-Neto, J. Positive effects of zinc supplementation on growth, GH, IGF1, and IGFBP3 in eutrophic children. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. JPEM 2012, 25, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.H.; Peerson, J.M.; Rivera, J.; Allen, L.H. Effect of supplemental zinc on the growth and serum zinc concentrations of prepubertal children: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 75, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, É.D.; de Brito, N.J.; Dantas, M.M.; Silva Ade, A.; Almeida, M.; Brandão-Neto, J. Effect of Zinc Supplementation on GH, IGF1, IGFBP3, OCN, and ALP in Non-Zinc-Deficient Children. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2015, 34, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarosz, M.; Olbert, M.; Wyszogrodzka, G.; Młyniec, K.; Librowski, T. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of zinc. Zinc-dependent NF-κB signaling. Inflammopharmacology 2017, 25, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.S.; Bao, B. Molecular Mechanisms of Zinc as a Pro-Antioxidant Mediator: Clinical Therapeutic Implications. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olechnowicz, J.; Tinkov, A.; Skalny, A.; Suliburska, J. Zinc status is associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, lipid, and glucose metabolism. J. Physiol. Sci. JPS 2018, 68, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrof, G.; Abdul-Wahab, A.; Proudfoot, L.; Pramanik, R.; Mellerio, J.E.; McGrath, J.A. Serum levels of high mobility group box 1 correlate with disease severity in recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Exp. Dermatol. 2013, 22, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, U.; Yang, H.; Harris, H. Extracellular HMGB1 as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2018, 22, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, J.D.; Johnson, L.B.; Tien, H.; Suchindran, C.; Brock, L.; Bauer, E.A.; Carter, D.M.; Sybert, V.; Lin, A.; Caldwell-Brown, D.; et al. Premature death and inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): Cumulative risk, as assessed by lifetable analysis of the national EB registry dataset. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1995, 4, 621. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, J.E.; Harmon, K.; Caldwell, C.C.; Wong, H.R. Prophylactic zinc supplementation reduces bacterial load and improves survival in a murine model of sepsis. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. A J. Soc. Crit. Care Med. World Fed. Pediatr. Intensive Crit. Care Soc. 2012, 13, e323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greffeuille, V.; Fortin, S.; Gibson, R.; Rohner, F.; Williams, A.; Young, M.F.; Houghton, L.; Ou, J.; Dijkhuizen, M.A.; Wirth, J.P.; et al. Associations between Zinc and Hemoglobin Concentrations in Preschool Children and Women of Reproductive Age: An Analysis of Representative Survey Data from the Biomarkers Reflecting Inflammation and Nutritional Determinants of Anemia (BRINDA) Project. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, L.A.; Parnell, W.R.; Thomson, C.D.; Green, T.J.; Gibson, R.S. Serum Zinc Is a Major Predictor of Anemia and Mediates the Effect of Selenium on Hemoglobin in School-Aged Children in a Nationally Representative Survey in New Zealand. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1670–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeng, S.S.; Chen, Y.H. Association of Zinc with Anemia. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhaleim, A.F.; Amer, A.Y.; Abdo Soliman, J.S. Association of Zinc Deficiency with Iron Deficiency Anemia and its Symptoms: Results from a Case-control Study. Cureus 2019, 1, e3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Ryu, M.-S. Cellular Zinc Deficiency Impairs Heme Biosynthesis in Developing Erythroid Progenitors. Nutrients 2023, 15, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, A. Role of Zinc and Copper in Erythropoiesis in Patients on Hemodialysis. J. Ren. Nutr. Off. J. Counc. Ren. Nutr. Natl. Kidney Found. 2022, 32, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, S.; Kiwaki, K.; Miyazaki, Y.; Hasuda, T. Zinc and IGF-I Concentrations in Pregnant Women with Anemia before and after Supplementation with Iron and/or Zinc. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1999, 18, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondaiah, P.; Yaduvanshi, P.S.; Sharp, P.A.; Pullakhandam, R. Iron and Zinc Homeostasis and Interactions: Does Enteric Zinc Excretion Cross-Talk with Intestinal Iron Absorption? Nutrients 2019, 11, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H.; Safargar, M.; Găman, M.A.; Akhgarjand, C.; Prabahar, K.; Zarezadeh, H.; Chan, X.Y.; Jamilian, P.; Kord-Varkaneh, H. Association of Higher Intakes of Dietary Zinc with Higher Ferritin or Hemoglobin: A Cross-sectional Study from NHANES (2017–2020). Biol. Trace Element Res. 2025, 203, 5603–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, E.; Sato, S.; Degawa, M.; Ono, T.; Lu, H.; Matsumura, D.; Nomura, M.; Moriyama, N.; Amaha, M.; Nakamura, T. Effects of Zinc Acetate Hydrate Supplementation on Renal Anemia with Hypozincemia in Hemodialysis Patients. Toxins 2022, 14, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.M.; Binnert, C.; Chiolero, R.L.; Taylor, W.; Raffoul, W.; Cayeux, M.-C.; Benathan, M.; Shenkin, A.; Tappy, L. Trace element supplementation after major burns increases burned skin trace element concentrations and modulates local protein metabolism but not whole-body substrate metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1301–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A.; Imran, J.; Madni, T.; Wolf, S.E. Nutrition and metabolism in burn patients. Burn. Trauma 2017, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, B.A.; Nakakura, A.M. Nutrition Considerations for Burn Patients: Optimizing Recovery and Healing. Eur. Burn. J. 2023, 4, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maares, M.; Haase, H. A Guide to Human Zinc Absorption: General Overview and Recent Advances of In Vitro Intestinal Models. Nutrients 2020, 12, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, C.C.; Kim, J.; Su, J.C.; Daniel, B.S.; Venugopal, S.S.; Rhodes, L.M.; Intong, L.R.; Law, M.G.; Murrell, D.F. Development, reliability, and validity of a novel Epidermolysis Bullosa Disease Activity and Scarring Index (EBDASI). J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 70, 89-97.e1-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.