Nutritional Regulation of Cardiac Metabolism and Function: Molecular and Epigenetic Mechanisms and Their Role in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Diet and Cardiac Metabolism: Molecular Regulation and Metabolic Adaptation

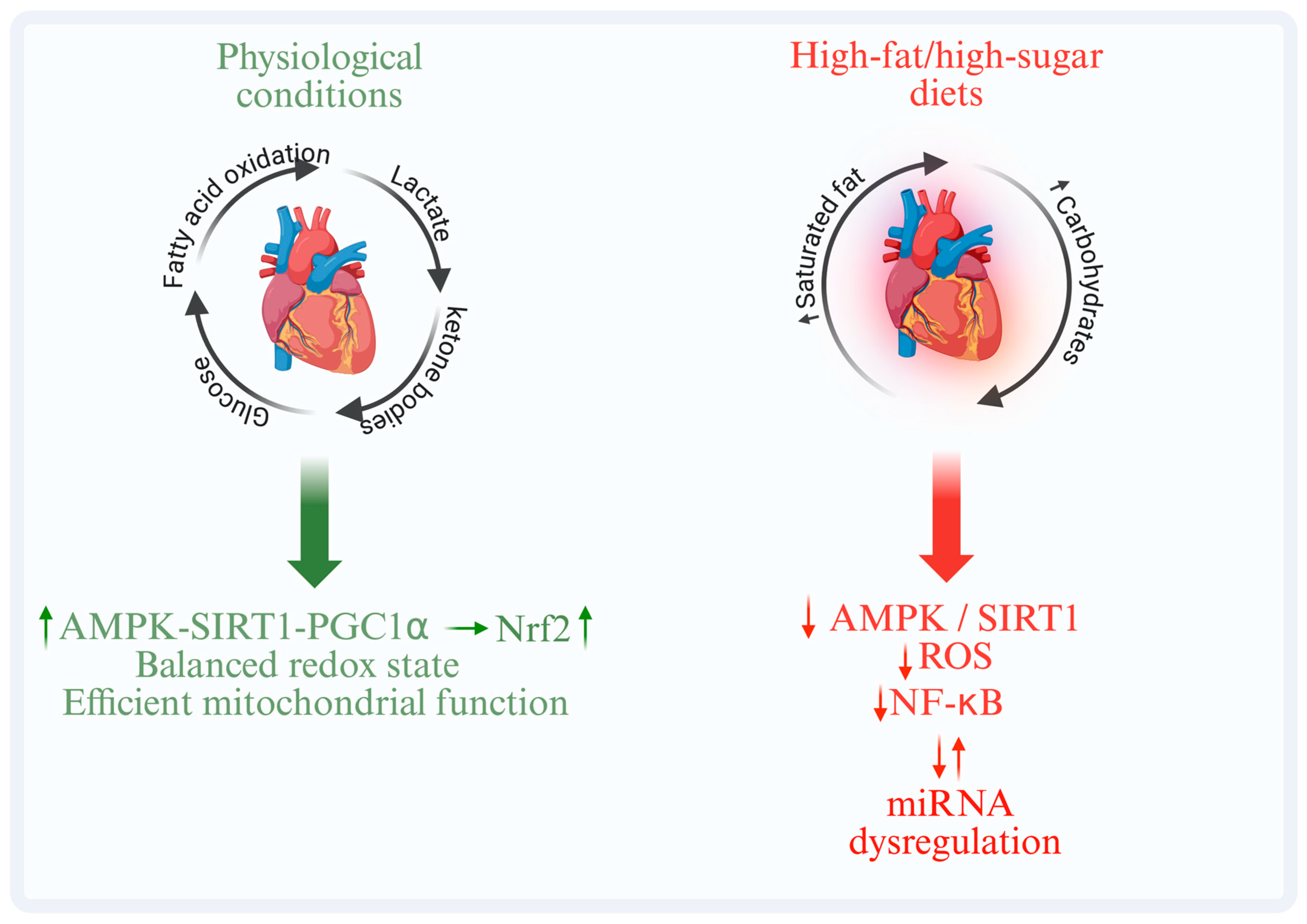

3.1. Signaling Pathways and Molecular Regulators of Cardiac Metabolism

3.2. Interplay Between Metabolism, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress

4. Diet, Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

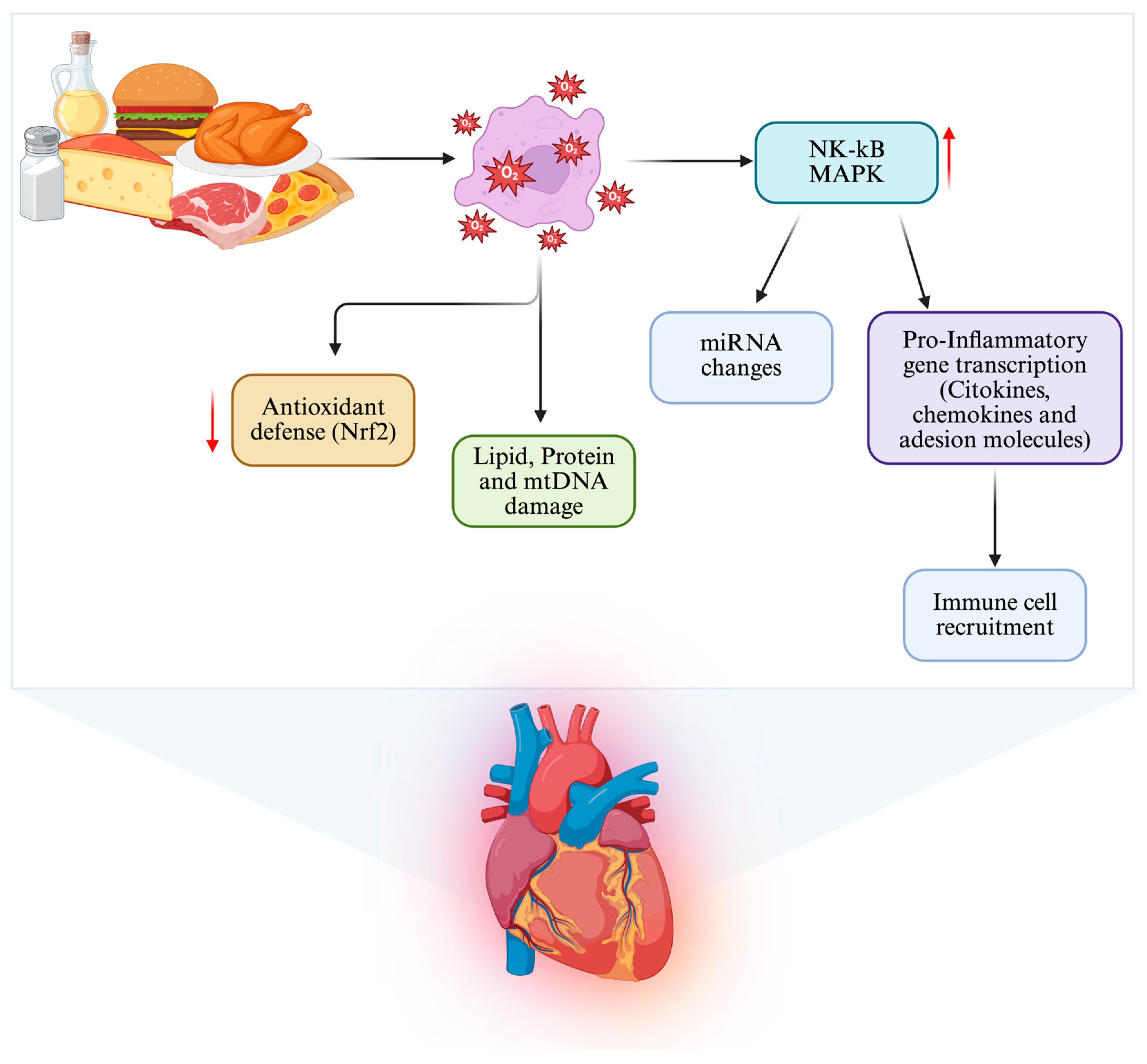

4.1. Activation of Inflammatory and Redox Pathways

4.2. Interaction Between Chronic Inflammation and Cardiac Remodeling

4.3. Modulatory Role of Bioactive Nutrients

5. Diet and Epigenetics in the Regulation of Cardiac Function

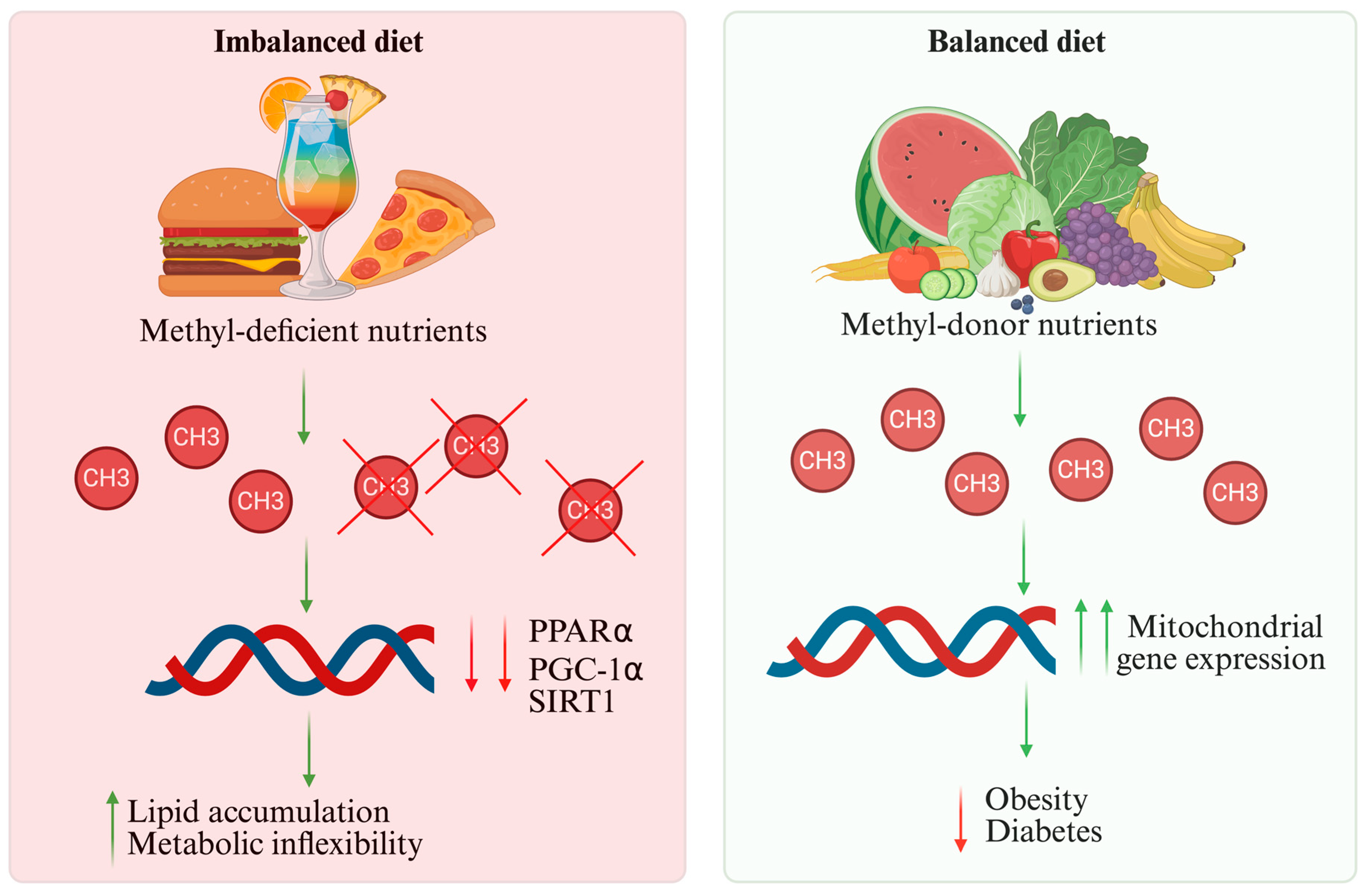

5.1. DNA Methylation and Cardiac Gene Regulation

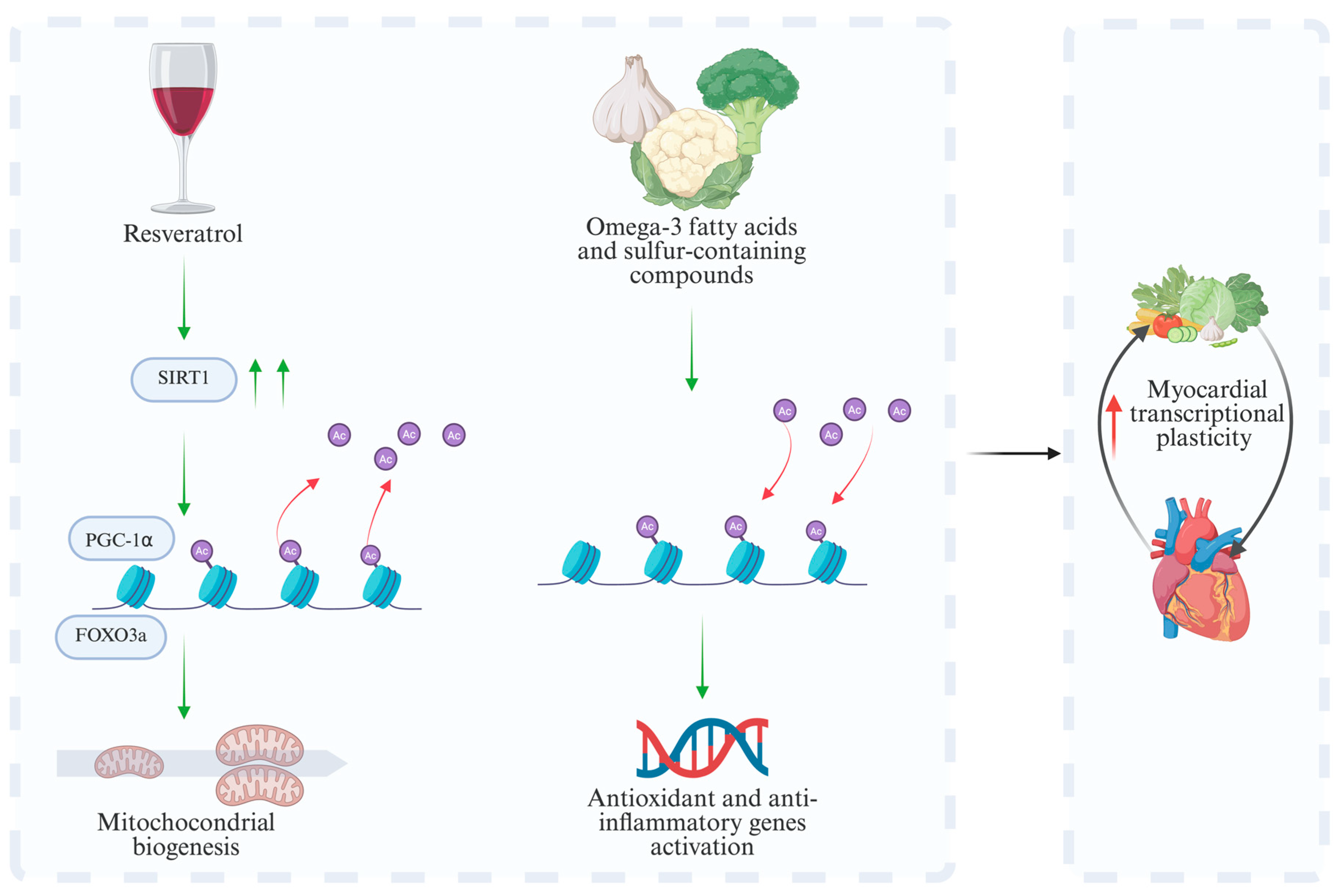

5.2. Histone Modifications and Control of Transcriptional Expression

5.3. Regulation of Non-Coding RNAs and Epigenetic Remodeling

5.4. Nutrient-Dependent Epigenetic Modulation of Cardiac Gene Programs

6. Cardioprotective Nutritional Strategies

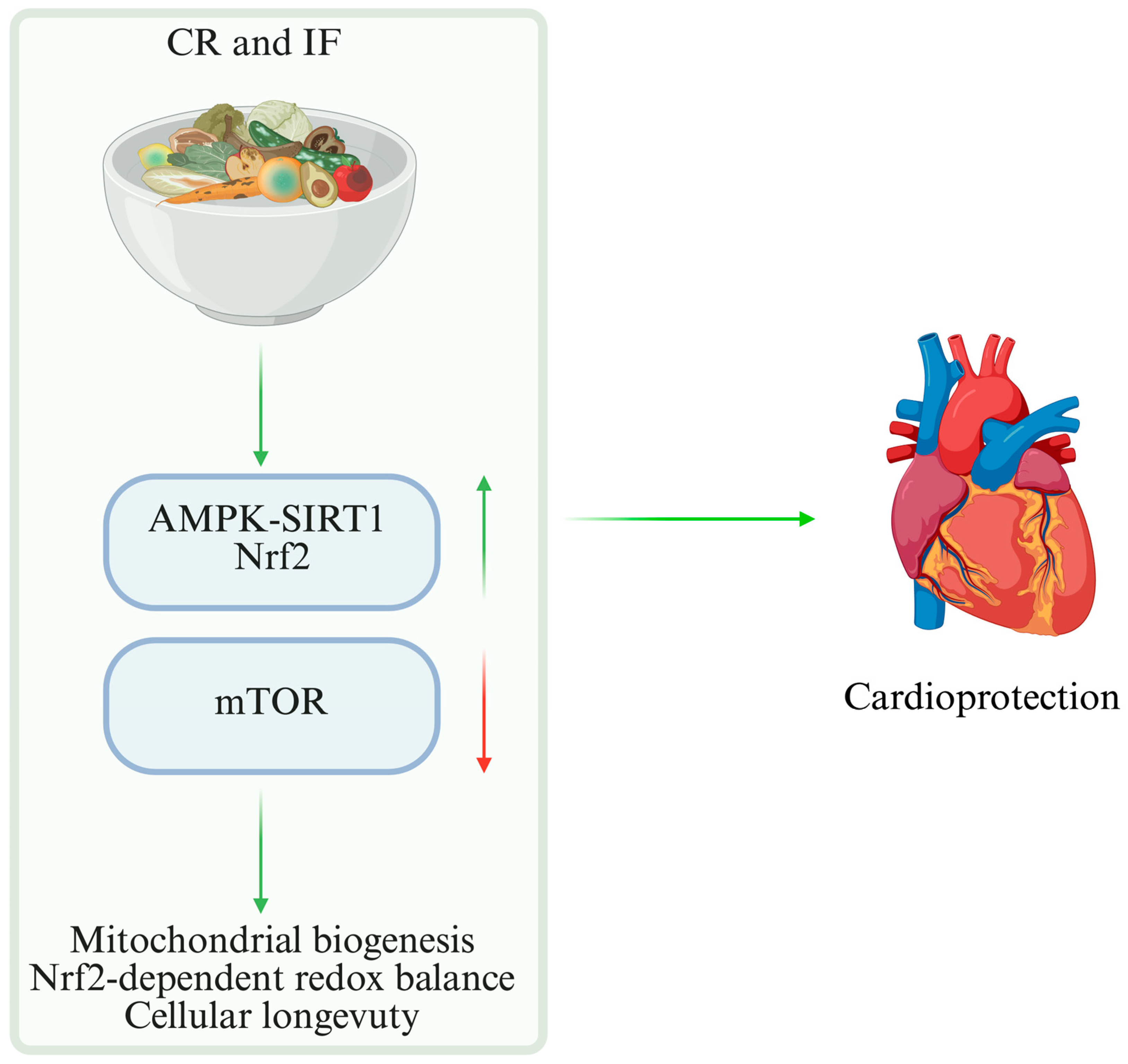

6.1. CR and IF

6.2. Mediterranean and Plant-Based Diets

6.3. Bioactive Nutrients and Nutraceutical Supplementation

6.4. Vegetarian and Vegan Diets: Clinical Evidence and Mechanisms

7. Microbiota, Metabolites, and the Heart

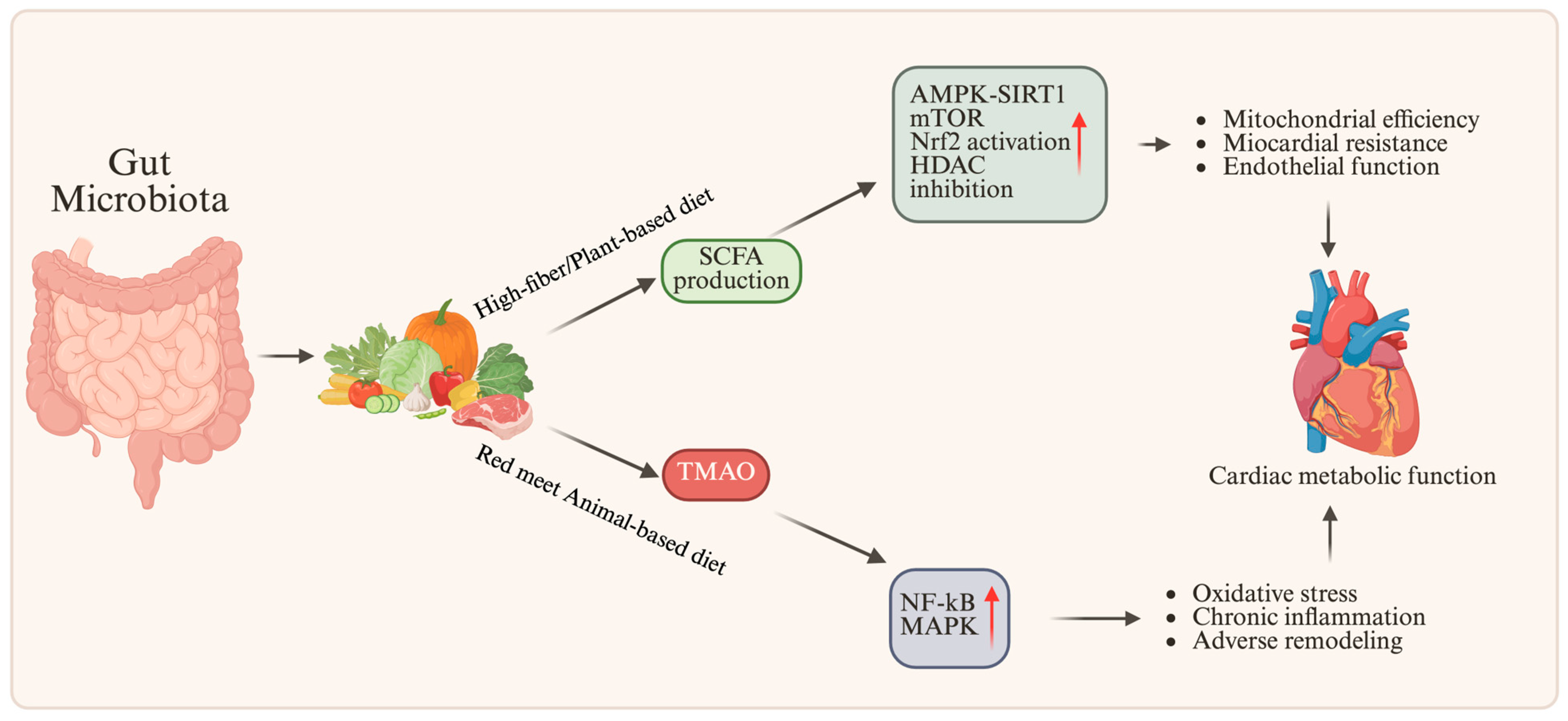

7.1. The Role of the Intestinal Microbiota in Cardiac Metabolism

7.2. Microbial Metabolites and Epigenetic Signaling

7.3. Nutritional Approaches Aimed at Modulating the Microbiota

8. Clinical Implications and Future Perspectives

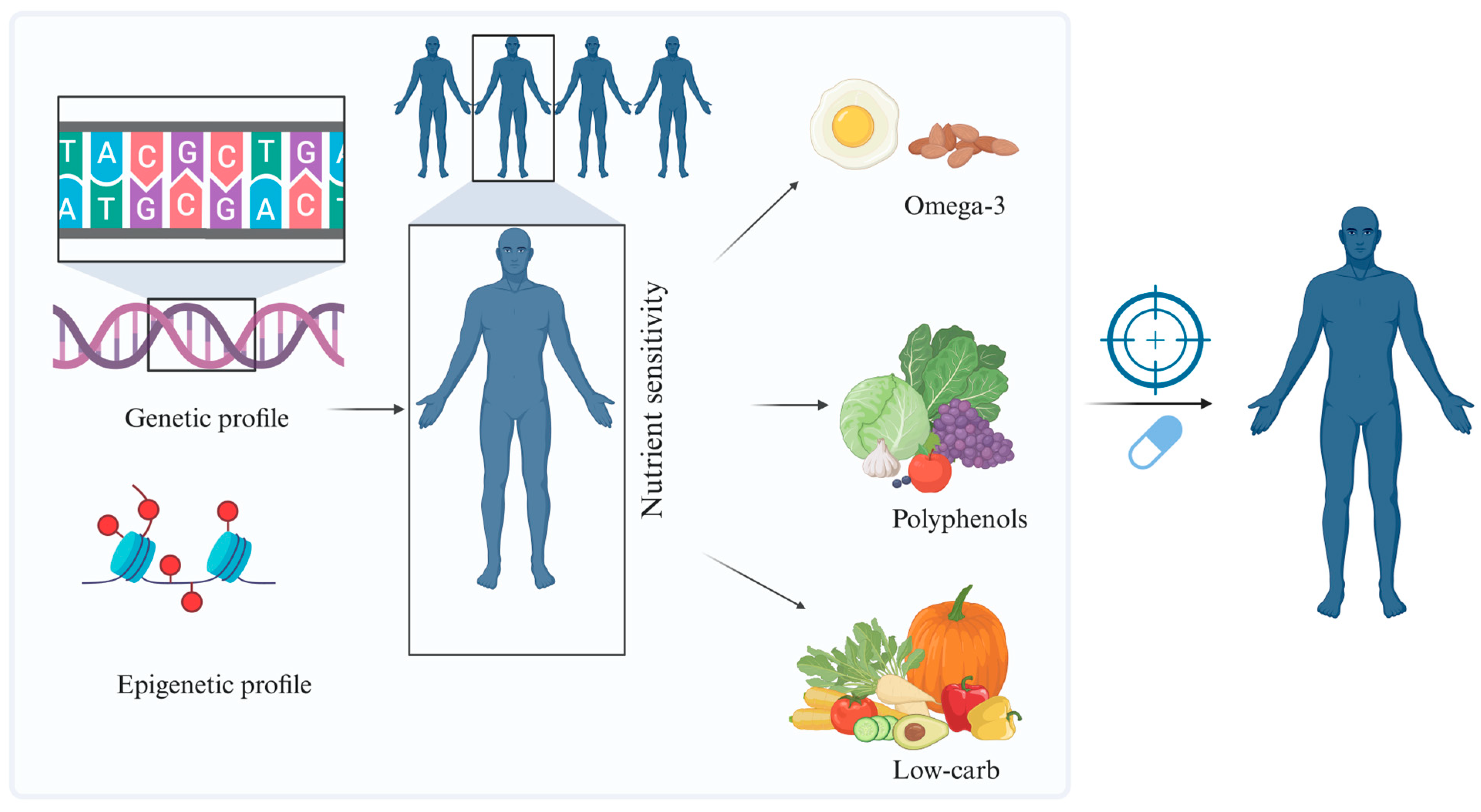

8.1. Personalized Nutrition and Precision Medicine in Cardiology

8.2. Dietary Interventions Integrated with Pharmacotherapy and Lifestyle Changes

8.3. Epigenetic Biomarkers and Translational Research

9. Distinction Between Mechanistic, Translational, and Clinical Evidence

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Akt | Protein kinase A |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| CR | Calorie restriction |

| CVDs | Cardiovascular diseases |

| DNMT | DNA methyltransferase |

| FOXO3a | Forkhead box O3a |

| HAT | Histone acetyltransferase |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| IF | Intermittent fasting |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PPARα | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| TET | Ten-Eleven Translocation |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-oxide |

References

- Stark, B.A.; DeCleene, N.K.; Desai, E.C.; Hsu, J.M.; Johnson, C.O.; Lara-Castor, L.; LeGrand, K.E.; A, B.; Aalipour, M.A.; Aalruz, H.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990-2023. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 86, 2167–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, S.; Hu, X.; Chen, F.; Li, D. A Review of Healthy Dietary Choices for Cardiovascular Disease: From Individual Nutrients and Foods to Dietary Patterns. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M. Intensity, Duration, and Context Dependency of the Responses to Nutrient Surplus and Deprivation Signaling in the Heart: Insights Into the Complexities of Cardioprotection. Circulation 2025, 152, 802–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meco, M.; Giustiniano, E.; Nisi, F.; Zulli, P.; Agosteo, E. MAPK, PI3K/Akt Pathways, and GSK-3β Activity in Severe Acute Heart Failure in Intensive Care Patients: An Updated Review. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Disease 2025, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondapalli, N.; Katari, V.; Dalal, K.K.; Paruchuri, S.; Thodeti, C.K. Microbiota in Gut-Heart Axis: Metabolites and Mechanisms in Cardiovascular Disease. Compr. Physiol. 2025, 15, e70024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez de Cedrón, M.; Moreno Palomares, R.; Ramírez de Molina, A. Metabolo-epigenetic interplay provides targeted nutritional interventions in chronic diseases and ageing. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1169168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodde, I.F.; van der Stok, J.; Smolenski, R.T.; de Jong, J.W. Metabolic and genetic regulation of cardiac energy substrate preference. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2007, 146, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Karwi, Q.G.; Wong, N.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Advances in myocardial energy metabolism: Metabolic remodelling in heart failure and beyond. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 1996–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Actis Dato, V.; Lange, S.; Cho, Y. Metabolic Flexibility of the Heart: The Role of Fatty Acid Metabolism in Health, Heart Failure, and Cardiometabolic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Zhang, L.; Gao, W.; Huang, C.; Huber, P.E.; Zhou, X.; Li, C.; Shen, G.; Zou, B. NAD+ metabolism: Pathophysiologic mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Jagannath, C. Crosstalk between metabolism and epigenetics during macrophage polarization. Epigenet. Chromatin 2025, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, M.; Yang, X.; Hu, Y.; Qiu, C.; Fu, Y.; Lan, X.; Luo, G.; Liu, Q.; Liu, M. Energy metabolism in cardiovascular diseases: Unlocking the hidden powerhouse of cardiac pathophysiology. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1617305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honka, H.; Solis-Herrera, C.; Triplitt, C.; Norton, L.; Butler, J.; DeFronzo, R.A. Therapeutic Manipulation of Myocardial Metabolism: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 2022–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantó, C.; Auwerx, J. PGC-1alpha, SIRT1 and AMPK, an energy sensing network that controls energy expenditure. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2009, 20, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, N.L.; Gomes, A.P.; Ling, A.J.; Duarte, F.V.; Martin-Montalvo, A.; North, B.J.; Agarwal, B.; Ye, L.; Ramadori, G.; Teodoro, J.S.; et al. SIRT1 is required for AMPK activation and the beneficial effects of resveratrol on mitochondrial function. Cell. Metab. 2012, 15, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiles, W.J.; Ovens, A.J.; Oakhill, J.S.; Kofler, B. The metabolic sensor AMPK: Twelve enzymes in one. Mol. Metab. 2024, 90, 102042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yang, G.; Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, T.; Xie, D.; Liu, Y.; et al. Energy metabolism: A critical target of cardiovascular injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. SIRT1 and energy metabolism. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2013, 45, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketema, E.B.; Lopaschuk, G.D. Post-translational Acetylation Control of Cardiac Energy Metabolism. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 723996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Paltzer, W.G.; Mahmoud, A.I. The Role of Metabolism in Heart Failure and Regeneration. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 702920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A. Crosstalk between Oxidative Stress and SIRT1: Impact on the Aging Process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 3834–3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, B.; Barnes, S.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Morrow, C.; Salvador, C.; Skibola, C.; Tollefsbol, T.O. Influences of diet and the gut microbiome on epigenetic modulation in cancer and other diseases. Clin. Epigenet. 2015, 7, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xu, C.; An, P.; Luo, Y.; Jiao, L.; Luo, J.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Therapeutic Perspectives in Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.; Gonçalves, A.; Morais, J.; Araujo, R.; Falcão-Pires, I. Diet-Induced Microbiome’s Impact on Heart Failure: A Double-Edged Sword. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupu, V.V.; Adam Raileanu, A.; Mihai, C.M.; Morariu, I.D.; Lupu, A.; Starcea, I.M.; Frasinariu, O.E.; Mocanu, A.; Dragan, F.; Fotea, S. The Implication of the Gut Microbiome in Heart Failure. Cells 2023, 12, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.H.; Seo, H.S.; Choo, W.J.; Choi, J.; Suh, J.; Cho, Y.H.; Lee, N.H. The Effect of Metabolic Syndrome on Myocardial Contractile Reserve during Exercise in Non-Diabetic Hypertensive Subjects. J. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2011, 19, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dina, C.; Tit, D.M.; Radu, A.; Bungau, G.; Radu, A.F. Obesity, Dietary Patterns, and Cardiovascular Disease: A Narrative Review of Metabolic and Molecular Pathways. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, A.H.; Appel, L.J.; Vadiveloo, M.; Hu, F.B.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Sacks, F.M.; Thorndike, A.N.; Van Horn, L.; Wylie-Rosett, J. 2021 Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 144, e472–e487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Maza-Bustindui, N.S.; León-Álvarez, M.; Ponce-Acosta, C.; Zarco-Morales, K.P.; Fermín-Martínez, C.A.; Antonio-Villa, N.E.; Bello-Chavolla, O.Y. Impact of cardiometabolic risk factors and its management on the reversion and progression of arterial stiffness. Npj Cardiovasc. Health 2025, 2, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korakas, E.; Dimitriadis, G.; Raptis, A.; Lambadiari, V. Dietary Composition and Cardiovascular Risk: A Mediator or a Bystander? Nutrients 2018, 10, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, K.; Otsu, K. Inflammation and metabolic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, E.; Sweet, I.R.; Hockenbery, D.M.; Pham, M.; Rizzo, N.O.; Tateya, S.; Handa, P.; Schwartz, M.W.; Kim, F. Activation of NF-kappaB by palmitate in endothelial cells: A key role for NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide in response to TLR4 activation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009, 29, 1370–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Fan, J.; Yu, H.; Chen, Z. Resveratrol attenuates high glucose-induced cardiomyocytes injury via interfering ROS-MAPK-NF-κB signaling pathway. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018, 11, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medoro, A.; Saso, L.; Scapagnini, G.; Davinelli, S. NRF2 signaling pathway and telomere length in aging and age-related diseases. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2024, 479, 2597–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Prieto, C.F.; Hernández-Nuño, F.; Rio, D.D.; Ruiz-Hurtado, G.; Aránguez, I.; Ruiz-Gayo, M.; Somoza, B.; Fernández-Alfonso, M.S. High-fat diet induces endothelial dysfunction through a down-regulation of the endothelial AMPK-PI3K-Akt-eNOS pathway. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, Y.Y. Comparative mathematical modeling reveals the differential effects of high-fat diet and ketogenic diet on the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway in heart. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 21, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Wei, J.; Zheng, H.; Zhou, N.; Xu, X.; Deng, X.; Liu, T.; Zou, Y. The immune system in cardiovascular diseases: From basic mechanisms to therapeutic implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minihane, A.M.; Vinoy, S.; Russell, W.R.; Baka, A.; Roche, H.M.; Tuohy, K.M.; Teeling, J.L.; Blaak, E.E.; Fenech, M.; Vauzour, D.; et al. Low-grade inflammation, diet composition and health: Current research evidence and its translation. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 999–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, R.; Liu, M.; Zhang, D. The role of myocardial fibrosis in the diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalopoulos, E.P.; Dufeys, C.; Bertrand, L.; Beauloye, C.; Horman, S. AMPK in cardiac fibrosis and repair: Actions beyond metabolic regulation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016, 91, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engin, A. Endothelial Dysfunction in Obesity and Therapeutic Targets. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2024, 1460, 489–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, C.D.; Conte, J.V. The pathophysiology of heart failure. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2012, 21, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, M.J.; Müller, P.; Lechner, K.; Stiebler, M.; Arndt, P.; Kunz, M.; Ahrens, D.; Schmeißer, A.; Schreiber, S.; Braun-Dullaeus, R.C. Arterial stiffness and vascular aging: Mechanisms, prevention, and therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Numazawa, S.; Tang, H.; Tang, X.; Han, X.; Li, J.; Yang, M.; Wang, Z.; et al. The crosstalk between Nrf2 and AMPK signal pathways is important for the anti-inflammatory effect of berberine in LPS-stimulated macrophages and endotoxin-shocked mice. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Cuevas, J.; Galicia-Moreno, M.; Monroy-Ramírez, H.C.; Sandoval-Rodriguez, A.; García-Bañuelos, J.; Santos, A.; Armendariz-Borunda, J. The Role of NRF2 in Obesity-Associated Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wende, A.R.; Abel, E.D. Lipotoxicity in the heart. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1801, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, C.L.; Roche, H.M. Nutritional Modulation of AMPK-Impact upon Metabolic-Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNicolantonio, J.J.; McCarty, M.F.; O’Keefe, J.H. Nutraceutical activation of Sirt1: A review. Open Heart 2022, 9, e002171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, B.; Zheng, B.; Liu, Y. Nrf2-mediated therapeutic effects of dietary flavones in different diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1240433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vors, C.; Le Barz, M.; Bourlieu, C.; Michalski, M.C. Dietary lipids and cardiometabolic health: A new vision of structure-activity relationship. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2020, 23, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieborak, A.; Schneider, R. Metabolic intermediates-Cellular messengers talking to chromatin modifiers. Mol. Metab. 2018, 14, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, S.; Yin, L.; Wang, F.; Luo, P.; Huang, H. Epigenetic regulation in cardiovascular disease: Mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Harst, P.; de Windt, L.J.; Chambers, J.C. Translational Perspective on Epigenetics in Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glier, M.B.; Green, T.J.; Devlin, A.M. Methyl nutrients, DNA methylation, and cardiovascular disease. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, M.M.; Guéant-Rodriguez, R.M.; Pooya, S.; Brachet, P.; Alberto, J.M.; Jeannesson, E.; Maskali, F.; Gueguen, N.; Marie, P.Y.; Lacolley, P.; et al. Methyl donor deficiency induces cardiomyopathy through altered methylation/acetylation of PGC-1α by PRMT1 and SIRT1. J. Pathol. 2011, 225, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolo, R.F.; McBreairty, L.E. The nutritional burden of methylation reactions. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2013, 16, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopczyńska, J.; Kowalczyk, M. The potential of short-chain fatty acid epigenetic regulation in chronic low-grade inflammation and obesity. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1380476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, O.S.; Sant, K.E.; Dolinoy, D.C. Nutrition and epigenetics: An interplay of dietary methyl donors, one-carbon metabolism and DNA methylation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T.X.; Lee, J. Dietary regulation of histone acetylases and deacetylases for the prevention of metabolic diseases. Nutrients 2012, 4, 1868–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouge, M.; Argmann, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Meziane, H.; Lerin, C.; Daussin, F.; Messadeq, N.; Milne, J.; Lambert, P.; Elliott, P.; et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha. Cell 2006, 127, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin, T.K.; Yu, A.P.; Yung, B.Y.; Yip, S.P.; Chan, L.W.; Wong, C.S.; Ying, M.; Rudd, J.A.; Siu, P.M. Modulating effect of SIRT1 activation induced by resveratrol on Foxo1-associated apoptotic signalling in senescent heart. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 2535–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, R.; Bermúdez, V.; Galban, N.; Garrido, B.; Santeliz, R.; Gotera, M.P.; Duran, P.; Boscan, A.; Carbonell-Zabaleta, A.K.; Durán-Agüero, S.; et al. Dietary Polyphenols and Gut Microbiota Cross-Talk: Molecular and Therapeutic Perspectives for Cardiometabolic Disease: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miękus, N.; Marszałek, K.; Podlacha, M.; Iqbal, A.; Puchalski, C.; Świergiel, A.H. Health Benefits of Plant-Derived Sulfur Compounds, Glucosinolates, and Organosulfur Compounds. Molecules 2020, 25, 3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante-Menéndez, J.; López-Pastor, A.R.; González-López, P.; Gómez-Hernández, A.; Escribano, O. The Interplay between Oxidative Stress and miRNAs in Obesity-Associated Hepatic and Vascular Complications. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.; Bestepe, F.; Vehbi, S.; Ghanem, G.F.; Blanton, R.M.; Icli, B. Obesity and Heart Failure: Mechanistic Insights and the Regulatory Role of MicroRNAs. Genes 2025, 16, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ponnusamy, M.; Liu, C.; Gao, J.; Wang, K.; Li, P. MicroRNA as a Therapeutic Target in Cardiac Remodeling. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1278436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, M.J.; Glynn, E.L.; Fry, C.S.; Dhanani, S.; Volpi, E.; Rasmussen, B.B. Essential amino acids increase microRNA-499, -208b, and -23a and downregulate myostatin and myocyte enhancer factor 2C mRNA expression in human skeletal muscle. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 2279–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanaghaei, M.; Tourkianvalashani, F.; Hekmatimoghaddam, S.; Ghasemi, N.; Rahaie, M.; Khorramshahi, V.; Sheikhpour, A.; Heydari, Z.; Pourrajab, F. Circulating miR-126 and miR-499 reflect progression of cardiovascular disease; correlations with uric acid and ejection fraction. Heart Int. 2016, 11, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gonzalo-Calvo, D.; van der Meer, R.W.; Rijzewijk, L.J.; Smit, J.W.; Revuelta-Lopez, E.; Nasarre, L.; Escola-Gil, J.C.; Lamb, H.J.; Llorente-Cortes, V. Serum microRNA-1 and microRNA-133a levels reflect myocardial steatosis in uncomplicated type 2 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, B.; Li, J.; Yuan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Dai, T.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Dietary sugar consumption and health: Umbrella review. BMJ 2023, 381, e071609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Hoes, A.W.; Agewall, S.; Albus, C.; Brotons, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Cooney, M.T.; Corrà, U.; Cosyns, B.; Deaton, C.; et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur. Heart. J. 2016, 37, 2315–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Wu, J.H. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: Effects on risk factors, molecular pathways, and clinical events. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 2047–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenanoglu, S.; Gokce, N.; Akalin, H.; Ergoren, M.C.; Beccari, T.; Bertelli, M.; Dundar, M. Implication of the Mediterranean diet on the human epigenome. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E44–E55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satija, A.; Hu, F.B. Plant-based diets and cardiovascular health. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 28, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.Y.; Kim, B.H. Fatty acids and epigenetics in health and diseases. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 3153–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V.; Nagu, P.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Sharma, M.; Parashar, A.; Sridhar, K. Epigenetics and Gut Microbiota Crosstalk: A potential Factor in Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disorders. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhana, K.; Aggarwal, N.T.; Voigt, R.M.; Ventrelle, J.; Rajan, K.B.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R.; Marcovina, S.M.; Liu, X.; Agarwal, P.; Tangney, C.; et al. Effect of weight loss through dietary interventions on cardiometabolic health in older adults. Int. J. Obes. 2025, 49, 2503–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, K.S.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Diet Quality Assessment and the Relationship between Diet Quality and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeo, F.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Hofer, S.J.; Kroemer, G. Caloric Restriction Mimetics against Age-Associated Disease: Targets, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Potential. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 592–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, V.D.; Anderson, R.M. Nutrition, longevity and disease: From molecular mechanisms to interventions. Cell 2022, 185, 1455–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.D.; Moehl, K.; Donahoo, W.T.; Marosi, K.; Lee, S.A.; Mainous, A.G., 3rd; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Mattson, M.P. Flipping the Metabolic Switch: Understanding and Applying the Health Benefits of Fasting. Obesity 2018, 26, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stekovic, S.; Hofer, S.J.; Tripolt, N.; Aon, M.A.; Royer, P.; Pein, L.; Stadler, J.T.; Pendl, T.; Prietl, B.; Url, J.; et al. Alternate Day Fasting Improves Physiological and Molecular Markers of Aging in Healthy, Non-obese Humans. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 462–476.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, E.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Estruch, R.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Fitó, M.; Martínez, J.A.; Corella, D. Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular health: Teachings of the PREDIMED study. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 330s–336s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Estruch, R.; Corella, D.; Fitó, M.; Ros, E. Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: Insights From the PREDIMED Study. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 58, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnefont-Rousselot, D. Resveratrol and Cardiovascular Diseases. Nutrients 2016, 8, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, I.U.H.; Bhat, R. Quercetin: A Bioactive Compound Imparting Cardiovascular and Neuroprotective Benefits: Scope for Exploring Fresh Produce, Their Wastes, and By-Products. Biology 2021, 10, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Mishra, S.; Chaturvedi, R.; Pandey, A. Therapeutic potential of curcumin in cardiovascular disease: Targeting atherosclerosis pathophysiology. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 190, 118412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Gea, A.; Ruiz-Canela, M. The Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Health. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannataro, R.; Fazio, A.; La Torre, C.; Caroleo, M.C.; Cione, E. Polyphenols in the Mediterranean Diet: From Dietary Sources to microRNA Modulation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, C.A.; Kjeldsen, E.W.; Frikke-Schmidt, R. Vegetarian or vegan diets and blood lipids: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 2609–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, P.S.; Kharaty, S.S.; Phillips, C.M. Plant-Based Diets and Lipid, Lipoprotein, and Inflammatory Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Disease: A Review of Observational and Interventional Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, N.D.; Alwarith, J.; Rembert, E.; Brandon, L.; Nguyen, M.; Goergen, A.; Horne, T.; do Nascimento, G.F.; Lakkadi, K.; Tura, A.; et al. A Mediterranean Diet and Low-Fat Vegan Diet to Improve Body Weight and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Randomized, Cross-over Trial. J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. 2022, 41, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, N.D.; Cohen, J.; Jenkins, D.J.; Turner-McGrievy, G.; Gloede, L.; Jaster, B.; Seidl, K.; Green, A.A.; Talpers, S. A low-fat vegan diet improves glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in a randomized clinical trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowska, I.; Olszak, J.; Formanowicz, P.; Formanowicz, D. Dietary Habits and Lifestyle, Including Cardiovascular Risk among Vegetarians and Omnivores during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Polish Population. Nutrients 2023, 15, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Xu, J.; Agarwal, U.; Gonzales, J.; Levin, S.; Barnard, N.D. A multicenter randomized controlled trial of a plant-based nutrition program to reduce body weight and cardiovascular risk in the corporate setting: The GEICO study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.J.; Cui, J.; Lin, Q.; Chen, X.Y.; Zhang, J.; Gao, E.H.; Wei, B.; Zhao, W. Protection of the enhanced Nrf2 deacetylation and its downstream transcriptional activity by SIRT1 in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 342, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Kroeger, C.M.; Cassidy, S.; Mitra, S.; Ribeiro, R.V.; Jose, S.; Masedunskas, A.; Senior, A.M.; Fontana, L. Vegetarian Dietary Patterns and Cardiometabolic Risk in People With or at High Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2325658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Bäckhed, F.; Landmesser, U.; Hazen, S.L. Intestinal Microbiota in Cardiovascular Health and Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2089–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z. Gut microbiome and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2020, 35, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petakh, P.; Duve, K.; Oksenych, V.; Behzadi, P.; Kamyshnyi, O. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic possibilities of short-chain fatty acids in posttraumatic stress disorder patients: A mini-review. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1394953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogal, A.; Valdes, A.M.; Menni, C. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between gut microbiota and diet in cardio-metabolic health. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1897212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; Dugar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.M.; et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canyelles, M.; Borràs, C.; Rotllan, N.; Tondo, M.; Escolà-Gil, J.C.; Blanco-Vaca, F. Gut Microbiota-Derived TMAO: A Causal Factor Promoting Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Bosch, C.; Boorman, E.; Zunszain, P.A.; Mann, G.E. Short-chain fatty acids as modulators of redox signaling in health and disease. Redox Biol. 2021, 47, 102165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A.; Mach, N. The Crosstalk between the Gut Microbiota and Mitochondria during Exercise. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahim, A.O.; Doddapaneni, N.S.P.; Salman, N.; Giridharan, A.; Thomas, J.; Sharma, K.; Abboud, E.; Rochill, K.; Shreelakshmi, B.; Gupta, V.; et al. The gut-heart axis: A review of gut microbiota, dysbiosis, and cardiovascular disease development. Ann. Med. Surg. 2025, 87, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Geng, J.; Zhao, J.; Ni, Q.; Zhao, C.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, L. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Exacerbates Cardiac Fibrosis via Activating the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, N.; Das, A.; Biswas, N.; Gnyawali, S.; Singh, K.; Gorain, M.; Polcyn, C.; Khanna, S.; Roy, S.; Sen, C.K. Urolithin A augments angiogenic pathways in skeletal muscle by bolstering NAD+ and SIRT1. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma, L.; Sanda, G.M.; Niculescu, L.S.; Deleanu, M.; Sima, A.V.; Stancu, C.S. Phenolic Compounds Exerting Lipid-Regulatory, Anti-Inflammatory and Epigenetic Effects as Complementary Treatments in Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, F.; Pellegrini, N.; Vannini, L.; Jeffery, I.B.; La Storia, A.; Laghi, L.; Serrazanetti, D.I.; Di Cagno, R.; Ferrocino, I.; Lazzi, C.; et al. High-level adherence to a Mediterranean diet beneficially impacts the gut microbiota and associated metabolome. Gut 2016, 65, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piya, M.K.; Harte, A.L.; McTernan, P.G. Metabolic endotoxaemia: Is it more than just a gut feeling? Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2013, 24, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witkowski, M.; Weeks, T.L.; Hazen, S.L. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licciardi, P.V.; Ververis, K.; Karagiannis, T.C. Histone deacetylase inhibition and dietary short-chain Fatty acids. ISRN Allergy 2011, 2011, 869647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roa-Díaz, Z.M.; Teuscher, J.; Gamba, M.; Bundo, M.; Grisotto, G.; Wehrli, F.; Gamboa, E.; Rojas, L.Z.; Gómez-Ochoa, S.A.; Verhoog, S.; et al. Gene-diet interactions and cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review of observational and clinical trials. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Song, Y.; Fu, K.; Gao, Z.; Liu, D.; He, W.; Yang, L.L. Energy metabolism in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.; Hernández Hernández, A. Effect of the Mediterranean diet in cardiovascular prevention. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2024, 77, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinu, F.R.; Beale, D.J.; Paten, A.M.; Kouremenos, K.; Swarup, S.; Schirra, H.J.; Wishart, D. Systems Biology and Multi-Omics Integration: Viewpoints from the Metabolomics Research Community. Metabolites 2019, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Planes, F.J.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Toledo, E.; Estruch, R.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Valdés-Más, R.; Mena, P.; Castañer, O.; Fitó, M.; et al. Recent advances in precision nutrition and cardiometabolic diseases. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2025, 78, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoch, M.; El Shamieh, S. Is There a Link Between Nutrition, Genetics, and Cardiovascular Disease? J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2020, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordovas, J.M.; Ferguson, L.R.; Tai, E.S.; Mathers, J.C. Personalised nutrition and health. BMJ 2018, 361, bmj.k2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.; Guo, J.; Gu, Z.; Tang, W.; Tao, H.; You, S.; Jia, D.; Sun, Y.; Jia, P. Machine learning and multi-omics integration: Advancing cardiovascular translational research and clinical practice. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, G.R.; Murphy, R.; Brough, L.; Butts, C.A.; Coad, J. Interindividual variability in gut microbiota and host response to dietary interventions. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 1059–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhernakova, D.V.; Kurilshikov, A.; Andreu-Sánchez, S.; Wang, D.; Augustijn, H.E.; Vich Vila, A.; Weersma, R.K.; Medema, M.H.; Netea, M.G.; et al. Influence of the microbiome, diet and genetics on inter-individual variation in the human plasma metabolome. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2333–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, M.N.; Salvador, A.C.; Barrington, W.T.; Gacasan, C.A.; D’Souza, E.M.; Deus Ramirez, L.; Threadgill, D.W.; Bennett, B.J. Gut microbiota and host genetics modulate the effect of diverse diet patterns on metabolic health. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 896348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiello, A.; Accardi, G.; Candore, G.; Gambino, C.M.; Mirisola, M.; Taormina, G.; Virruso, C.; Caruso, C. Nutrient sensing pathways as therapeutic targets for healthy ageing. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2017, 21, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmer, R.J.; Flammer, A.J.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. The Mediterranean diet, its components, and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Med. 2015, 128, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmancey, R.; Wilson, C.R.; Taegtmeyer, H. Adaptation and maladaptation of the heart in obesity. Hypertension 2008, 52, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, A.A.; Hill, B.G. Metabolic Coordination of Physiological and Pathological Cardiac Remodeling. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler-Botija, C.; Gálvez-Montón, C.; Bayés-Genís, A. Epigenetic Biomarkers in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secci, R.; Hartmann, A.; Walter, M.; Grabe, H.J.; Van der Auwera-Palitschka, S.; Kowald, A.; Palmer, D.; Rimbach, G.; Fuellen, G.; Barrantes, I. Biomarkers of geroprotection and cardiovascular health: An overview of omics studies and established clinical biomarkers in the context of diet. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 2426–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcena, M.L.; Aslam, M.; Norman, K.; Ott, C.; Ladilov, Y. Role of AMPK and Sirtuins in Aging Heart: Basic and Translational Aspects. Aging Dis. 2024, 16, 3335–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillarisetti, S. A review of Sirt1 and Sirt1 modulators in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Recent Pat. Cardiovasc. Drug Discov. 2008, 3, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.V.; Steffen, L.M.; Nayor, M.; Reis, J.P.; Jacobs, D.R.; Allen, N.B.; Lloyd-Jones, D.; Meyer, K.; Cole, J.; Piaggi, P.; et al. Dietary metabolic signatures and cardiometabolic risk. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pathway/ Regulator | Main Role | Stimuli/Activators | Main Effects | Models | Consequences of Dysfunction | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPARα | Regulates transcription of genes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation | Unsaturated fatty acids, ketone bodies | Enhances lipid utilization and prevents accumulation of lipotoxic intermediates | Human, animals, in vitro | Chronic exposure to saturated fats leads to metabolic inflexibility and cardiac dysfunction | [13] |

| AMPK | Principal cellular energy sensor (AMP/ATP ratio) | Increased AMP/ATP ratio, metabolic stress | Stimulates substrate oxidation, mitochondrial biogenesis, and antioxidant defenses | Animals, in vitro | Chronic caloric excess reduces its activity, impairing cardiac metabolic efficiency | [16] |

| mTOR | Nutrient-sensitive anabolic regulator | Nutrient overload * | Promotes protein synthesis and cell growth | Animals, in vitro | Sustained activation drives maladaptive cardiac hypertrophy; caloric restriction restores balance | [17] |

| SIRT1/PGC-1α | Integrates redox and energy pathways, regulates mitochondrial gene expression | Polyphenols, omega-3 fatty acids | Enhances oxidative efficiency and preserves cardiac function | Animals, in vitro | Mitochondrial dysfunction and loss of energetic homeostasis | [18] |

| Nutrient or Dietary Pattern | Main Pathways Modulated | Effect on Oxidative/Inflammatory Balance | Models | Cardiac Functional Impact | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated fats and simple sugars | ↑ NF-κB, ↓ Nrf2 | ↑ ROS and cytokine production, reduced antioxidant capacity | Human, animals, in vitro | Fibrosis, reduced contractile reserve | [30,46] |

| Mediterranean diet | ↑ AMPK, ↑ SIRT1 | ↓ inflammation, ↑ antioxidant response | Animals, in vitro | Improved endothelial and metabolic function | [48] |

| Polyphenols and omega-3 PUFA | ↑ Nrf2, ↑ PPARα | ↓ lipid peroxidation, ↓ NF-κB activation | Animals, in vitro | Enhanced energy efficiency, ↓ cardiac remodeling | [50] |

| CR | ↑ AMPK | ↓ ROS, ↑ mitochondrial efficiency | Human | Increased myocardial resilience and adaptive capacity | [51] |

| Nutrient/Dietary Component | Epigenetic Mechanism | Models | Functional Effect on the Heart | Typical Amount for Benefit | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folate 1, choline 2, methionine 3, betaine 4 | DNA methylation via DNMT modulation and methyl-donor supply | Human, animals, in vitro | Restores proper methylation, enhances mitochondrial function, reduces lipid accumulation | 400–800 µg/day 1, 425–550 mg/day 2, 13–15 mg/kg/day 3, 2–6 g/day 4 | [57,58] |

| Saturated fats and simple sugars | Altered DNA methylation and miRNA expression | Human, animals, in vitro | Promotes fibrosis, apoptosis, oxidative stress, and metabolic inflexibility | Limit intake: <10% total daily energy from saturated fats; added sugars <25 g/day | [71,72] |

| SCFAs | DNMT and HDAC inhibition; modulation of methyl-donor availability | Human, animals, in vitro | Improves redox balance, enhances antioxidant gene expression, and supports gut–heart communication | 3–5 g/day (from fiber) | [58] |

| Resveratrol (polyphenols) | SIRT1 activation and histone deacetylation | Animals, in vitro | Promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, improves oxidative stress resistance | 150–500 mg/day | [61,62] |

| Omega-3 fatty acids | HDAC modulation and histone acetylation | Human, animals, in vitro | Reduces inflammation and enhances antioxidant capacity | 1–3 g/day EPA + DHA | [73] |

| Sulfur compounds (e.g., garlic and cruciferous vegetables) | HDAC inhibition | Human, animals, in vitro | Enhances antioxidant defenses, reduces vascular inflammation | 30–60 mg/day sulforaphane (from cruciferous vegetables), 5–10 mg/day allicin (from garlic) | [64] |

| Polyphenols and unsaturated fats (Mediterranean diet) | miRNA regulation (↑ miR-133a, miR-499; ↓ miR-21, miR-34a) | Human | Improves contractility, limits fibrosis and apoptosis | Diet-based: ~30–50 g olive oil, 200–300 g vegetables, 20–40 g nuts/day | [68,69,70,74] |

| Diet Type | Main Components | Molecular Mechanisms | Models | Main Cardiac Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean diet | Olive oil, fish, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, red wine | Activation of SIRT1/PGC-1α, Nrf2 upregulation, modulation of miRNA expression | Human | Reduced inflammation and oxidative stress, improved endothelial function and lipid metabolism | [84,85] |

| Plant-based diet | Legumes, whole grains, nuts, fruits, vegetables, soy products | Reduction in oxidative stress, modulation of SCFA and gut microbiota composition | Human | Lower CVD risk, enhanced insulin sensitivity, improved mitochondrial metabolism | [75] |

| Nutrient | Potential Issue in Vegetarian/Vegan Patients | Main Sources/Supplementation | Practical Clinical Considerations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B12 | High risk of deficiency and hyperhomocysteinemia, especially in vegans | Fortified foods, oral B12 supplements | Mandatory supplementation in vegans; often advisable in older adults and in patients on metformin or proton pump inhibitors; monitor serum B12 and homocysteine. | [92,93,94,95,96,99] |

| Iodine | Inadequate intake or, less frequently, excessive intake from seaweed | Iodized salt, seaweed (with caution), fortified foods | Recommend iodized salt; avoid excessive seaweed consumption in patients with thyroid disorders. | [95,97] |

| Selenium | Low intake in regions with selenium-poor soils | Brazil nuts, seeds, whole grains, low-dose supplements | Consider supplementation in low-selenium areas; interpret status in the context of overall diet and comorbidities. | [95,97] |

| Zinc | Mild deficiency risk, particularly with poorly varied plant-based diets | Legumes, seeds, nuts, whole grains | Encourage food preparation methods that enhance bioavailability (soaking, sprouting, fermentation). | [95,97] |

| Iron | Increased risk of deficiency in specific groups (e.g., premenopausal women) | Legumes, tofu, whole grains, seeds, leafy green vegetables | Combine with vitamin C-rich foods; monitor hemoglobin and ferritin in high-risk individuals. | [95,97] |

| Calcium | Potentially low intake, especially in strict vegan diets | Calcium-set tofu, leafy greens, mineral waters, fortified plant milks | Assess total intake; consider calcium-fortified foods if dietary intake is insufficient. | [95,97] |

| Vitamin D | Common insufficiency regardless of dietary pattern | Sun exposure, vitamin D supplements | In cardiac patients, assessment of serum 25(OH)D and supplementation is often warranted. | [86,91] |

| Omega-3 (EPA/DHA) | Low direct intake of EPA/DHA in the absence of fish | Flaxseed, chia, walnuts (ALA); microalgae-based EPA/DHA supplements | Consider microalgae-derived EPA/DHA in patients with established CVD or hypertriglyceridemia. | [73,86,91] |

| Protein quality | Suboptimal essential amino acid profile when plant proteins are not diversified | Legumes, soy foods, whole grains, nuts, seeds | Promote a varied combination of plant protein sources to ensure adequate total protein and essential amino acid intake. | [95,97,99] |

| Microbiota-Derived Profile | Predominant Dietary Pattern | Microbiota Functional State | Epigenetic Modulation | Key Signaling Pathways | Cardiac and Translational Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCFA | Fiber-rich, Mediterranean, plant-based diets | Eubiotic, saccharolytic microbiota | HDAC inhibition; DNMT modulation → pro-adaptive epigenetic remodeling | ↑ AMPK–SIRT1; ↑ Nrf2; ↓ NF-κB | Improved mitochondrial efficiency, reduced inflammation, enhanced metabolic flexibility | [76,77] |

| TMAO | Red meat-rich, high-fat diets | Dysbiotic, proteolytic microbiota | Increased DNA methylation of antioxidant genes → maladaptive epigenetic imprinting | ↑ NF-κB; ↑ MAPK; ↓ Nrf2 | Endothelial dysfunction, fibrosis, adverse remodeling, increased CVD risk | [100] |

| Microbial polyphenol metabolites (urolithin A, gallic acid) | Polyphenol-rich diets | Eubiotic | miRNA modulation; DNA hypomethylation | ↑ SIRT1/PGC-1α | Anti-fibrotic effects, improved mitochondrial function | [110,111] |

| Combined | Main Pathways Involved | Molecular and Metabolic Effects | Models | Cardiovascular Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean diet + statins | ↑ AMPK, ↑ SIRT1, ↓ mTOR | ↓ TMAO, improved endothelial function | Human | ↑ ventricular compliance, ↓ atherosclerotic risk | [118,128] |

| Metformin + low-carbohydrate diet | ↑ AMPK, enhanced mitochondrial oxidation | ↑ cardiac energy efficiency, ↑ metabolic flexibility | Animals, In vitro | Improved exercise tolerance, ↓ oxidative stress | [130] |

| Polyphenol-rich diet + ACE inhibitors | ↑ SIRT1, ↓ NF-κB | ↓ inflammation and myocardial remodeling | Human, animals, in vitro | ↓ fibrosis, ↑ diastolic function | [48] |

| Omega-3 PUFA + β-blockers | ↑ PPARα, ↑ AMPK | ↑ fatty acid utilization, ↓ plasma triglycerides | Human, animals, in vitro | ↓ arrhythmias, ↑ cardiac electrical stability | [127] |

| Caloric restriction + moderate exercise | ↓ mTOR, ↑ mitochondrial biogenesis | ↑ metabolic resilience, ↓ ROS | Human, animals | Improved myocardial plasticity, ↓ ischemic events | [129] |

| Dietary Pattern/Nutrient | Key Molecular Pathways | Type of Evidence | Strength of Evidence * | Notes/Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | AMPK, SIRT1/PGC-1α, autophagy | Strong mechanistic; moderate translational; limited clinical | ●●●○ | Human evidence short-term only | [78,79,80,81,82,83,129] |

| IF | Ketone metabolism, AMPK, Nrf2 | Strong mechanistic; emerging human observational | ●●○○ | Protocol heterogeneity | [80,81,82,83] |

| Mediterranean Diet | Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant pathways | Moderate observational; limited mechanistic | ●●●○ | Confounding difficult to control | [84,85,86,118] |

| Polyphenols | SIRT1 activation, histone acetylation | Strong mechanistic; weak clinical | ●●○○ | Bioavailability issues | [61,62,73] |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids | Membrane signaling, anti-inflammatory | Moderate mechanistic; moderate clinical | ●●●○ | Dose and purity variation | [73,86,127] |

| SCFAs | HDAC inhibition, gut–heart axis | Emerging mechanistic | ●○○○ | Limited human data | [76,77,100] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Capasso, L.; Mele, D.; Casalino, R.; Favale, G.; Rollo, G.; Verrilli, G.; Conte, M.; Bontempo, P.; Carafa, V.; Altucci, L.; et al. Nutritional Regulation of Cardiac Metabolism and Function: Molecular and Epigenetic Mechanisms and Their Role in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. Nutrients 2026, 18, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010093

Capasso L, Mele D, Casalino R, Favale G, Rollo G, Verrilli G, Conte M, Bontempo P, Carafa V, Altucci L, et al. Nutritional Regulation of Cardiac Metabolism and Function: Molecular and Epigenetic Mechanisms and Their Role in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010093

Chicago/Turabian StyleCapasso, Lucia, Donato Mele, Rosaria Casalino, Gregorio Favale, Giulia Rollo, Giulia Verrilli, Mariarosaria Conte, Paola Bontempo, Vincenzo Carafa, Lucia Altucci, and et al. 2026. "Nutritional Regulation of Cardiac Metabolism and Function: Molecular and Epigenetic Mechanisms and Their Role in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010093

APA StyleCapasso, L., Mele, D., Casalino, R., Favale, G., Rollo, G., Verrilli, G., Conte, M., Bontempo, P., Carafa, V., Altucci, L., & Nebbioso, A. (2026). Nutritional Regulation of Cardiac Metabolism and Function: Molecular and Epigenetic Mechanisms and Their Role in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. Nutrients, 18(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010093