Associations of the Trajectories of Dietary Pattern and Hypertension: Results from the CHNS Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

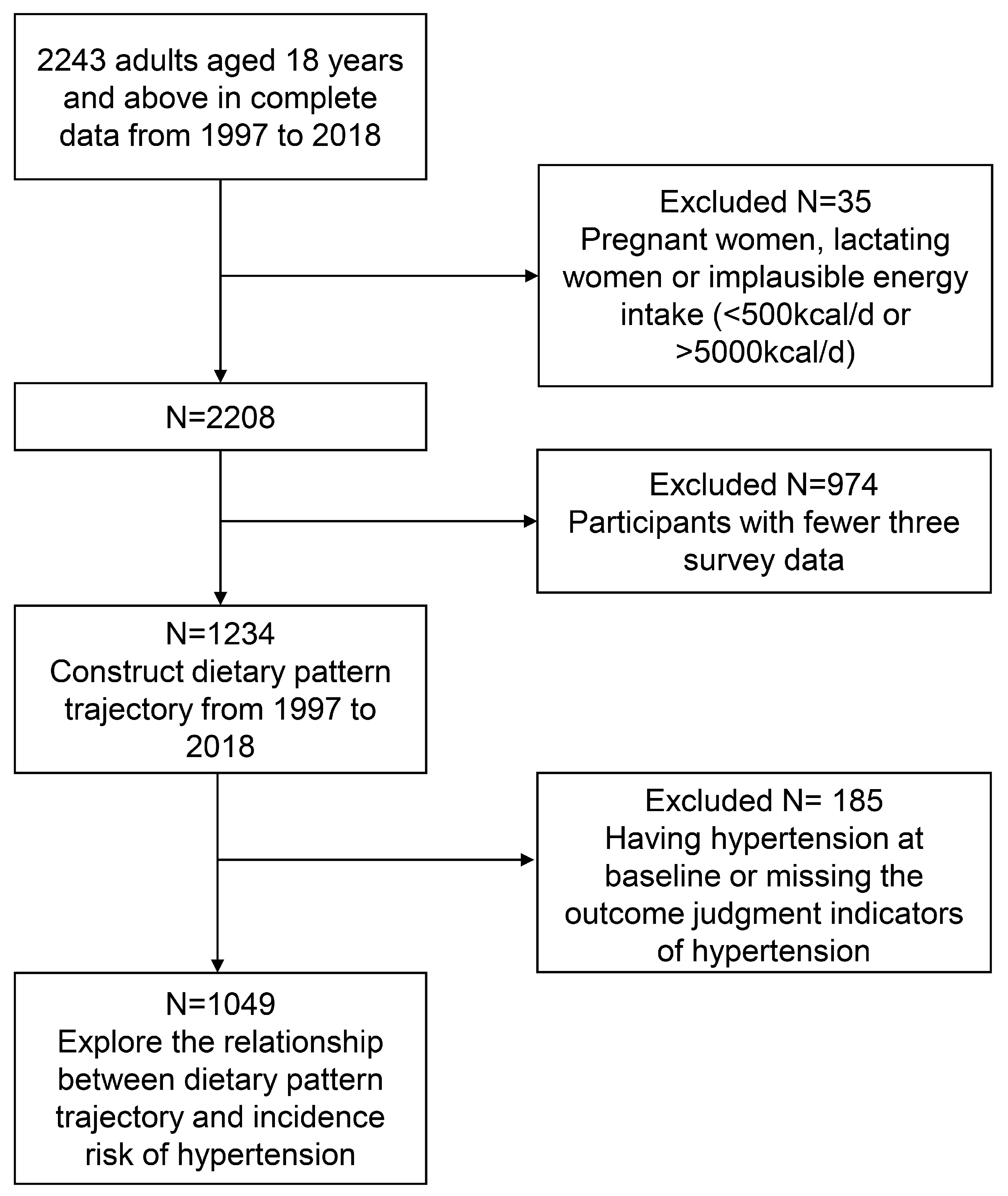

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Definition of Hypertension

2.3. Diet Intake

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Sensitivity Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Extraction and Analysis of Dietary Patterns

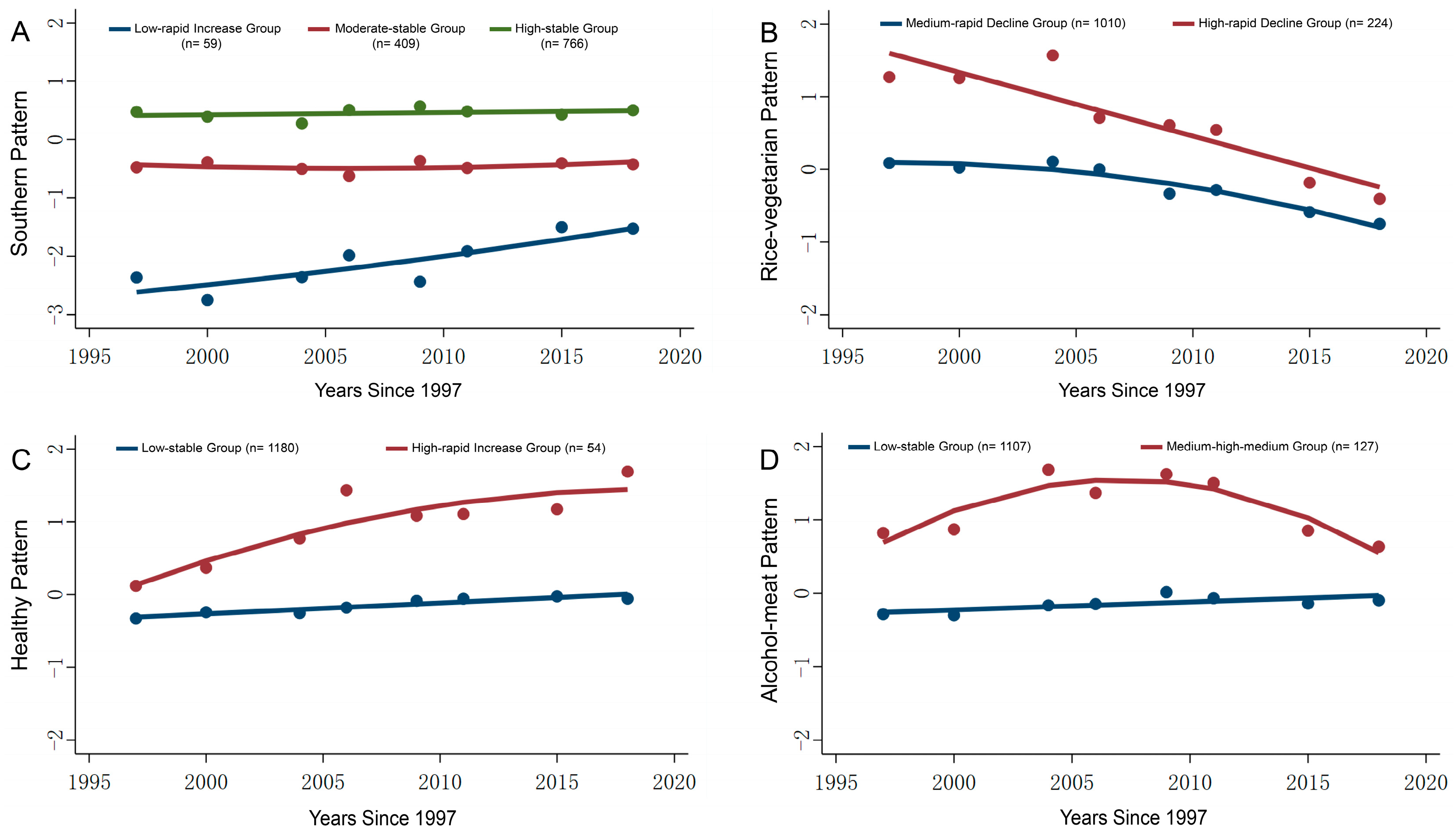

3.2. Construction of Dietary Pattern Trajectories

3.3. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population Based on Dietary Pattern Trajectory Grouping

3.4. Dietary Characteristics of the Study Population Based on Dietary Pattern Trajectory Grouping

3.5. Association of Dietary Pattern Trajectories and Hypertension Incidence Risk

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CHNS | China Health and Nutrition Survey |

| SBP | systolic blood pressure |

| DBP | diastolic blood pressure |

| BMI | body mass index |

| SD | standard deviation |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| GBTM | group-based trajectory model |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| AvePP | average posterior probability |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| CI | confidence interval |

References

- Zhou, B.; Perel, P.; Mensah, G.A.; Ezzati, M. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kario, K.; Okura, A.; Hoshide, S.; Mogi, M. The WHO Global report 2023 on hypertension warning the emerging hypertension burden in globe and its treatment strategy. Hypertens. Res. 2024, 47, 1099–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.G. Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension (2024 revision). J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2025, 22, 1–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Chaimani, A.; Schwedhelm, C.; Toledo, E.; Pünsch, M.; Hoffmann, G.; Boeing, H. Comparative effects of different dietary approaches on blood pressure in hypertensive and pre-hypertensive patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2674–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippou, C.D.; Thomopoulos, C.G.; Kouremeti, M.M.; Sotiropoulou, L.I.; Nihoyannopoulos, P.I.; Tousoulis, D.M.; Tsioufis, C.P. Mediterranean diet and blood pressure reduction in adults with and without hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3191–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.; Gaskin, E.; Ji, C.; Miller, M.A.; Cappuccio, F.P. The effect of plant-based dietary patterns on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled intervention trials. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caligiuri, S.P.B.; Pierce, G.N. A review of the relative efficacy of dietary, nutritional supplements, lifestyle, and drug therapies in the management of hypertension. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3508–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Elia, L.; Dinu, M.; Sofi, F.; Volpe, M.; Strazzullo, P.; SINU Working Group, Endorsed by SIPREC. 100% Fruit juice intake and cardiovascular risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective and randomised controlled studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2449–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Ahmed, M.; Ha, V.; Jefferson, K.; Malik, V.; Ribeiro, P.A.B.; Zuchinali, P. Dairy Product Consumption and Cardiovascular Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillo, A.; Salvi, L.; Coruzzi, P.; Salvi, P.; Parati, G. Sodium Intake and Hypertension. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cespedes, E.M.; Hu, F.B. Dietary patterns: From nutritional epidemiologic analysis to national guidelines. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 899–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morze, J.; Danielewicz, A.; Hoffmann, G.; Schwingshackl, L. Diet Quality as Assessed by the Healthy Eating Index Alternate Healthy Eating Index Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Score, and Health Outcomes: A Second Update of a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 1998–2031.e1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamnia, T.T.; Sargent, G.M.; Kelly, M. Dietary patterns and associations with metabolic risk factors for non-communicable disease. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Byles, J.; Shi, Z.; McElduff, P.; Hall, J. Dietary pattern transitions, and the associations with BMI, waist circumference, weight and hypertension in a 7-year follow-up among the older Chinese population: A longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Guo, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, T. Exploring the association of dietary patterns with the risk of hypertension using principal balances analysis and principal component analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Du, W.; Huang, F.; Li, L.; Bai, J.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H. Longitudinal study of dietary patterns and hypertension in adults: China Health and Nutrition Survey 1991–2018. Hypertens. Res. 2023, 46, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Du, W.; Huang, F.; Jiang, H.; Bai, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H. Twenty-Five-Year Trends in Dietary Patterns among Chinese Adults from 1991 to 2015. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhai, F.Y.; Du, S.F.; Popkin, B.M. The China Health and Nutrition Survey, 1989–2011. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Committee for Guideline R. 2018 Chinese Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension-A report of the Revision Committee of Chinese Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 182–241. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Li, Q.; He, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Qin, X. Quantity and variety of food groups consumption and the risk of diabetes in adults: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5710–5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsenburg, L.K.; Rieckmann, A.; Bengtsson, J.; Jensen, A.K.; Rod, N.H. Application of life course trajectory methods to public health data: A comparison of sequence analysis and group-based multi-trajectory modeling for modelling childhood adversity trajectories. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 340, 116449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Guo, L.; Wang, B.; Zuo, H. Dietary Patterns in Association with Hypertension: A Community-Based Study in Eastern China. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 926390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton, S.A.; Ball, K.; Mishra, G.D.; Crawford, D.A. Dietary patterns of adolescents and risk of obesity and hypertension. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appannah, G.; Murray, K.; Trapp, G.; Dymock, M.; Oddy, W.H.; Ambrosini, G.L. Dietary pattern trajectories across adolescence and early adulthood and their associations with childhood and parental factors. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Pahkala, K.; Juonala, M.; Rovio, S.P.; Sabin, M.A.; Rönnemaa, T.; Buscot, M.-J.; Smith, K.J.; Männistö, S.; Jula, A.; et al. Dietary Pattern Trajectories from Youth to Adulthood and Adult Risk of Impaired Fasting Glucose: A 31-year Cohort Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e2078–e2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Schwedhelm, C.; Hoffmann, G.; Knüppel, S.; Iqbal, K.; Andriolo, V.; Bechthold, A.; Schlesinger, S.; Boeing, H. Food Groups and Risk of Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roerecke, M.; Tobe, S.W.; Kaczorowski, J.; Bacon, S.L.; Vafaei, A.; Hasan, O.S.M.; Krishnan, R.J.; Raifu, A.O.; Rehm, J. Sex-Specific Associations Between Alcohol Consumption and Incidence of Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.; Kim, M.K.; Shin, J.; Lee, N.; Woo, H.W.; Choi, B.Y.; Shin, M.-H.; Shin, D.H.; Lee, Y.-H. Positive association of alcohol consumption with incidence of hypertension in adults aged 40 years and over: Use of repeated alcohol consumption measurements. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 3125–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roerecke, M.; Kaczorowski, J.; Tobe, S.W.; Gmel, G.; Hasan, O.S.M.; Rehm, J. The effect of a reduction in alcohol consumption on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e108–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, W.; Cai, A.; Li, L.; Feng, Y. Longitudinal Trajectories of Alcohol Consumption with All-Cause Mortality, Hypertension, and Blood Pressure Change: Results from CHNS Cohort, 1993–2015. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S. Alcohol Consumption Hypertension, and Cardiovascular Health Across the Life Course: There Is No Such Thing as a One-Size-Fits-All Approach. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e009698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Shan, S.; Cheng, G. Association between the prudent dietary pattern and blood pressure in Chinese adults is partially mediated by body composition. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1131126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasdar, Y.; Hamzeh, B.; Moradi, S.; Mohammadi, E.; Cheshmeh, S.; Darbandi, M.; Faramani, R.S.; Najafi, F. Healthy eating index 2015 and major dietary patterns in relation to incident hypertension; a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2023 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global burden of 292 causes of death in 204 countries and territories and 660 subnational locations, 1990–2023: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 1811–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, B.; Wu, J.; Qian, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, X. Interaction of Dietary Sodium-to-potassium Ratio Dinner Energy Ratio on Prevalence of Hypertension in Inner Mongolia China. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 33, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, X.; Lu, H.; Wu, J.; Xue, M.; Qian, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, X. The interactive association between sodium intake, alcohol consumption and hypertension among elderly in northern China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shi, Z. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption Associated with Incident Hypertension among Chinese Adults-Results from China Health and Nutrition Survey 1997–2015. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Qiao, Q.; Feng, X.; Jin, A.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Lei, S. Cost-Effectiveness of Salt Substitute and Salt Supply Restriction in Eldercare Facilities: The DECIDE-Salt Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2355564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cao, Z.; Li, J.; King, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, L. Associations of Combined Lifestyle Factors with MAFLD and the Specific Subtypes in Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults: The Dongfeng-Tongji Cohort Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Timmermans, E.J.; Zou, D.; Grobbee, D.E.; Zhou, S.; Vaartjes, I. Impact of green space exposure on blood pressure in Guangzhou, China: Mediation by air pollution, mental health, physical activity, and weight status. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 356, 124251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Food Species | Southern Pattern | Rice-Vegetarian Pattern | Healthy Pattern | Alcohol-Meat Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat products | −0.769 | −0.140 | −0.023 | 0.135 |

| Aquatic products | 0.478 | 0.125 | 0.092 | 0.307 |

| Other grains | −0.402 | 0.016 | −0.044 | −0.093 |

| Vegetables | −0.027 | 0.731 | 0.054 | −0.013 |

| Rice | 0.405 | 0.667 | −0.150 | −0.248 |

| Pastry products | 0.435 | −0.457 | −0.043 | 0.072 |

| Pickled vegetables | 0.047 | 0.406 | −0.068 | 0.097 |

| Dairy products | −0.083 | 0.006 | 0.699 | −0.116 |

| Fruits | 0.132 | −0.141 | 0.668 | 0.058 |

| Nuts | 0.018 | 0.179 | 0.342 | 0.144 |

| Eggs | 0.180 | −0.125 | 0.277 | 0.020 |

| Alcoholic beverages | −0.121 | 0.193 | −0.091 | 0.633 |

| Offal | 0.048 | −0.090 | −0.134 | 0.474 |

| Pork | 0.275 | −0.065 | 0.245 | 0.389 |

| Other livestock meats | 0.063 | −0.083 | 0.237 | 0.372 |

| Bean products | 0.184 | 0.028 | 0.083 | 0.370 |

| Poultry | −0.053 | 0.013 | 0.305 | 0.342 |

| Characteristics | Southern Pattern | Rice-Vegetarian Pattern | Healthy Pattern | Alcohol-Meat Pattern | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Rapid Rise and Medium-Stable Group | High-Stable Group | p | Medium-Rapid Increase Group | High-Rapid Decline Group | p | Low-Stable Group | High-Rapid Increase Group | p | Low-Stable Group | Medium-High-Medium Group | p | |

| n | 389 | 660 | 845 | 204 | 1003 | 46 | 939 | 110 | ||||

| Age (y) | 41.7 ± 12.8 | 39.5 ± 12.2 | 0.007 | 40.7 ± 12.9 | 38.9 ± 10.2 | 0.065 | 40.1 ± 12.4 | 44.5 ± 12.6 | 0.019 | 40.4 ± 12.7 | 39.6 ± 10.6 | 0.528 |

| Male, n (%) | 183 (47.0) | 327 (49.5) | 0.472 | 383 (45.3) | 127 (62.3) | <0.001 | 493 (49.2) | 17 (37.0) | 0.142 | 424 (45.2) | 86 (78.2) | <0.001 |

| Rural, n (%) | 293 (75.3) | 438 (66.4) | 0.003 | 537 (63.6) | 194 (95.1) | <0.001 | 724 (72.2) | 7 (15.2) | <0.001 | 651 (69.3) | 80 (72.7) | 0.533 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.7 ± 2.4 | 22.0 ± 2.9 | 0.156 | 22.0 ± 2.8 | 21.4 ± 2.4 | 0.007 | 21.9 ± 2.7 | 22.6 ± 3.1 | 0.083 | 21.9 ± 2.7 | 22.3 ± 2.6 | 0.146 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 109.0 ± 13.2 | 109.2 ± 11.5 | 0.839 | 109.1 ± 12.3 | 109.2 ± 11.1 | 0.944 | 109.1 ± 12.2 | 109.6 ± 10.7 | 0.807 | 108.9 ± 12.3 | 111.0 ± 10.1 | 0.109 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 71.2 ± 9.4 | 70.9 ± 8.7 | 0.712 | 70.9 ± 8.9 | 71.4 ± 8.9 | 0.538 | 71.0 ± 9.0 | 71.4 ± 8.2 | 0.782 | 70.8 ± 9.0 | 73.0 ± 8.3 | 0.023 |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.393 | 0.074 | 0.510 | 0.280 | ||||||||

| Married | 316 (81.2) | 555 (84.1) | 691 (81.8) | 180 (88.2) | 830 (82.8) | 41 (89.1) | 774 (82.4) | 97 (88.2) | ||||

| Unmarried/divorced/widowed | 72 (18.5) | 102 (15.5) | 151 (17.9) | 23 (11.3) | 169 (16.8) | 5 (10.9) | 161 (17.1) | 13 (11.8) | ||||

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Education, n (%) | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| Primary school or below | 190 (48.8) | 251 (38.0) | 330 (39.1) | 111 (54.4) | 436 (43.5) | 5 (10.9) | 412 (43.9) | 29 (26.4) | ||||

| Middle school | 123 (31.6) | 218 (33.0) | 276 (32.7) | 65 (31.9) | 327 (32.6) | 14 (30.4) | 298 (31.7) | 43 (39.1) | ||||

| High school or above | 70 (18.0) | 182 (27.6) | 226 (26.7) | 26 (12.7) | 226 (22.5) | 26 (56.5) | 215 (22.9) | 37 (33.6) | ||||

| Missing | 6 (1.5) | 9 (1.4) | 13 (1.5) | 2 (1.0) | 14 (1.4) | 1 (2.2) | 14 (1.5) | 1 (0.9) | ||||

| Smoking, n (%) | 127 (32.6) | 199 (30.2) | 0.293 | 250 (29.6) | 76 (37.3) | 0.095 | 316 (31.5) | 10 (21.7) | 0.365 | 269 (28.6) | 57 (51.8) | <0.001 |

| Drinking, n (%) | 187 (48.1) | 251 (38.0) | 0.001 | 340 (40.2) | 98 (48.0) | 0.119 | 420 (41.9) | 18 (39.1) | 0.845 | 359 (38.2) | 79 (71.8) | <0.001 |

| PAL, n (%) | 0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Light | 107 (27.5) | 234 (35.5) | 324 (38.3) | 17 (8.3) | 303 (30.2) | 38 (82.6) | 312 (33.2) | 29 (26.4) | ||||

| Moderate | 58 (14.9) | 116 (17.6) | 162 (19.2) | 12 (5.9) | 168 (16.7) | 6 (13.0) | 137 (14.6) | 37 (33.6) | ||||

| Vigorous | 222 (57.1) | 308 (46.7) | 355 (42.0) | 175 (85.8) | 528 (52.6) | 2 (4.3) | 486 (51.8) | 44 (40.0) | ||||

| Missing | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Diabetes | 7 (1.8) | 12 (1.8) | 0.730 | 18 (2.1) | 1 (0.5) | 0.155 | 18 (1.8) | 1 (2.2) | <0.001 | 19 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.237 |

| Dietary Pattern Trajectories | Crude Model HR (95% CI) | Model 1 HR (95% CI) | Model 2 HR (95% CI) | Model 3 HR (95% CI) | Model 4 HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern pattern | |||||

| Low-rapid rise and medium-stable group | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| High-stable group | 0.78 (0.65, 0.92) | 0.85 (0.71, 1.01) | 0.83 (0.69, 0.99) | 0.81 (0.68, 0.98) | 0.80 (0.67, 0.96) |

| Rice-vegetarian pattern | |||||

| Medium-rapid increase group | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| High-rapid decline group | 0.97 (0.78, 1.19) | 1.03 (0.82, 1.29) | 1.05 (0.84, 1.33) | 1.06 (0.84, 1.33) | 1.06 (0.85, 1.34) |

| Healthy pattern | |||||

| Low-stable group | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| High-rapid increase group | 0.76 (0.47, 1.23) | 0.57 (0.35, 0.95) | 0.57 (0.34, 0.96) | 0.60 (0.36, 0.99) | 0.58 (0.35, 0.97) |

| Alcohol-meat pattern | |||||

| Low-stable group | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Medium-high-medium group | 1.46 (1.14, 1.87) | 1.48 (1.15, 1.91) | 1.53 (1.17, 1.99) | 1.46 (1.12, 1.91) | 1.48 (1.13, 1.94) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Shan, D.; Cao, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Ouyang, Y.; Gong, C.; Tang, Y.; Yao, P.; et al. Associations of the Trajectories of Dietary Pattern and Hypertension: Results from the CHNS Cohort. Nutrients 2026, 18, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010039

Li H, Zhang Z, Shan D, Cao Z, Li J, Liu L, Ouyang Y, Gong C, Tang Y, Yao P, et al. Associations of the Trajectories of Dietary Pattern and Hypertension: Results from the CHNS Cohort. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Hongxia, Zhuangyu Zhang, Die Shan, Zhiqiang Cao, Jingjing Li, Ling Liu, Yingying Ouyang, Chenrui Gong, Yuhan Tang, Ping Yao, and et al. 2026. "Associations of the Trajectories of Dietary Pattern and Hypertension: Results from the CHNS Cohort" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010039

APA StyleLi, H., Zhang, Z., Shan, D., Cao, Z., Li, J., Liu, L., Ouyang, Y., Gong, C., Tang, Y., Yao, P., Song, Y., & Liu, S. (2026). Associations of the Trajectories of Dietary Pattern and Hypertension: Results from the CHNS Cohort. Nutrients, 18(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010039