Sex Moderates the Mediating Effect of Physical Activity in the Relationship Between Dietary Habits and Sleep Quality in University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Sample Size

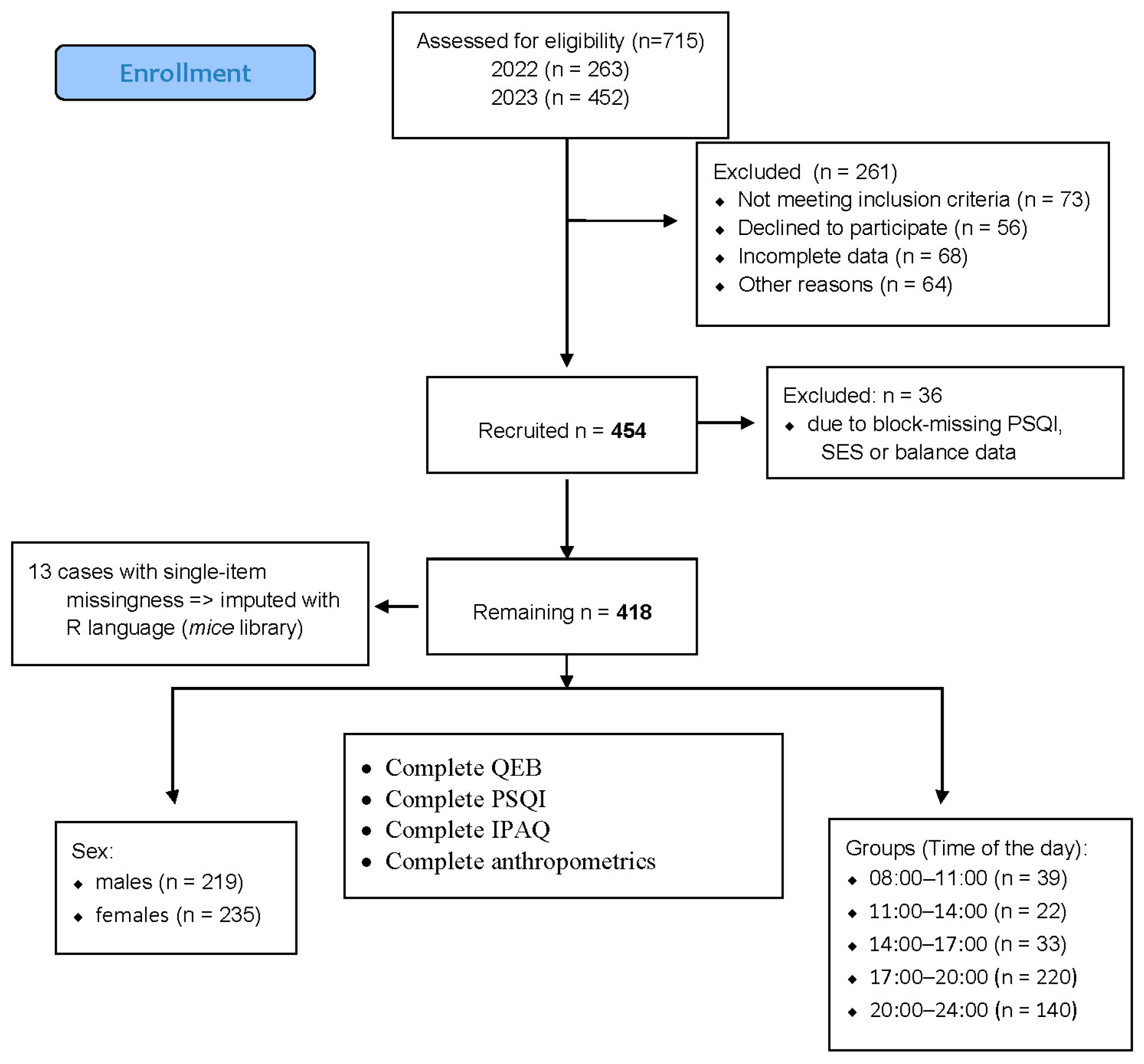

2.4. Participants

2.5. Anthropometric Measurements

2.6. Questionnaire Measurements

2.6.1. Sleep Quality—Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

2.6.2. Physical Activity—International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)

2.6.3. Dietary Intake Questionnaire—Questionnaire Eating Behaviours (QEB)

2.7. Handling and Imputation of Missing Data

2.8. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

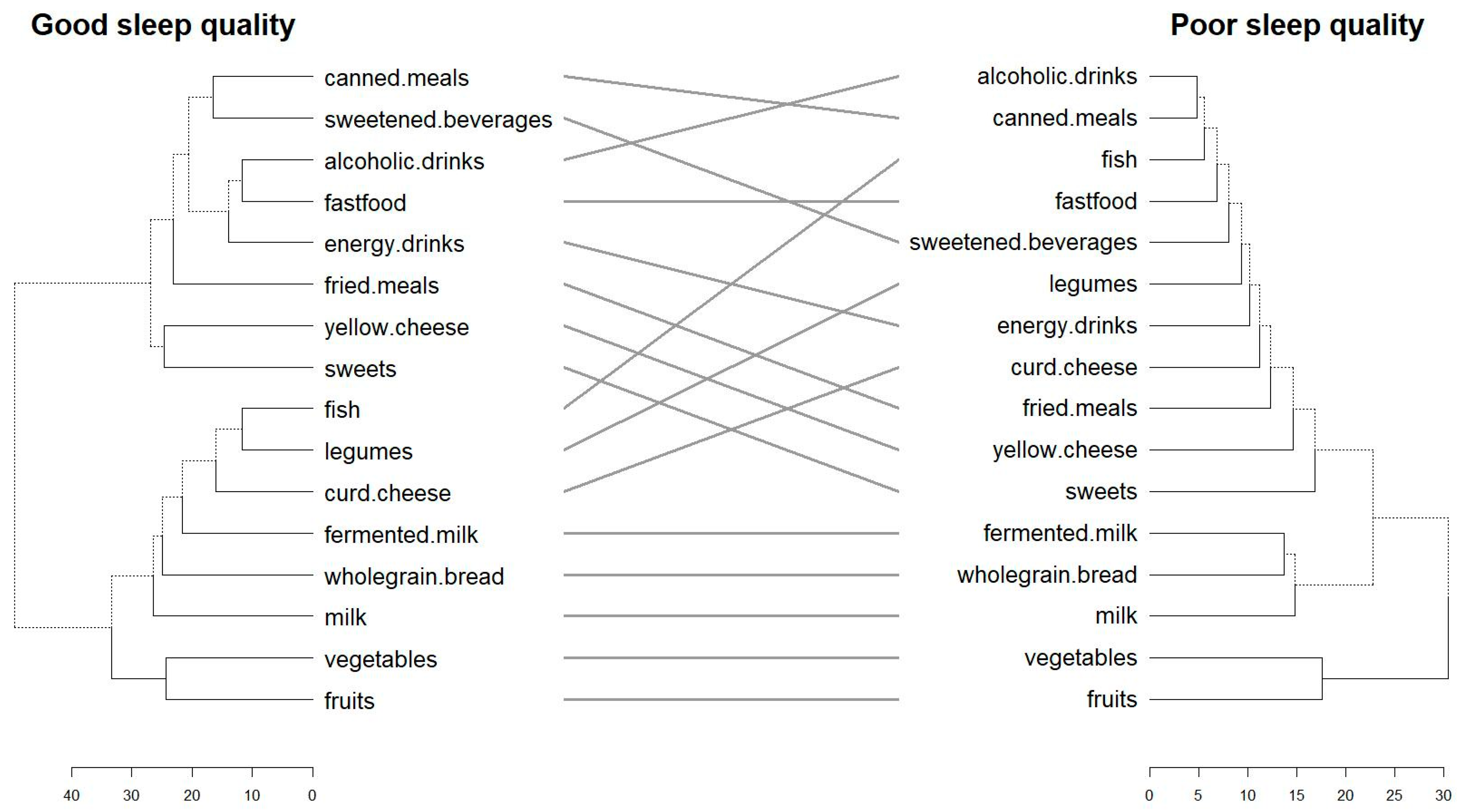

3.2. Congruence and Divergence in Dietary Patterns by Sleep Quality

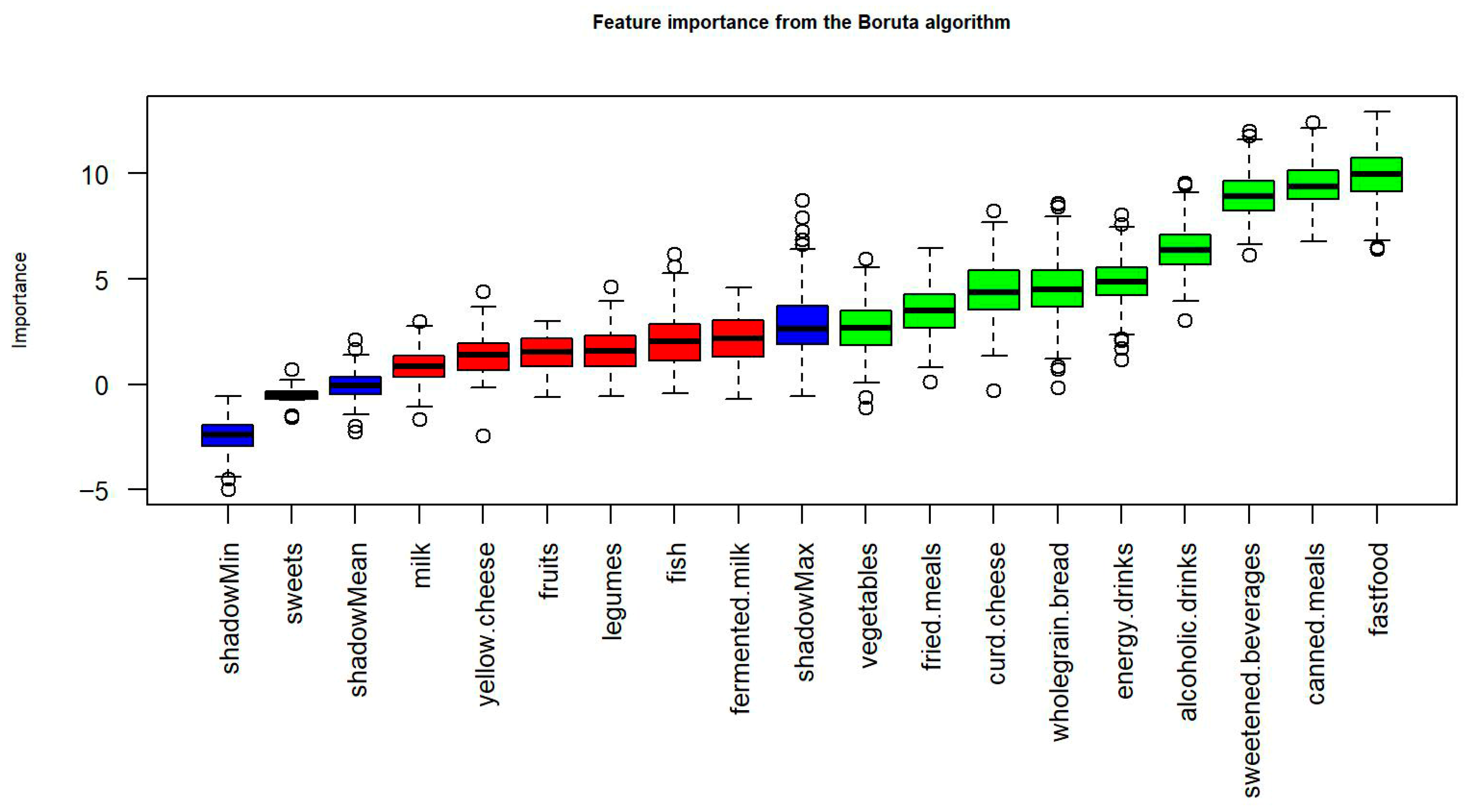

3.3. Key Dietary Behaviours Distinguishing Good and Poor Sleepers

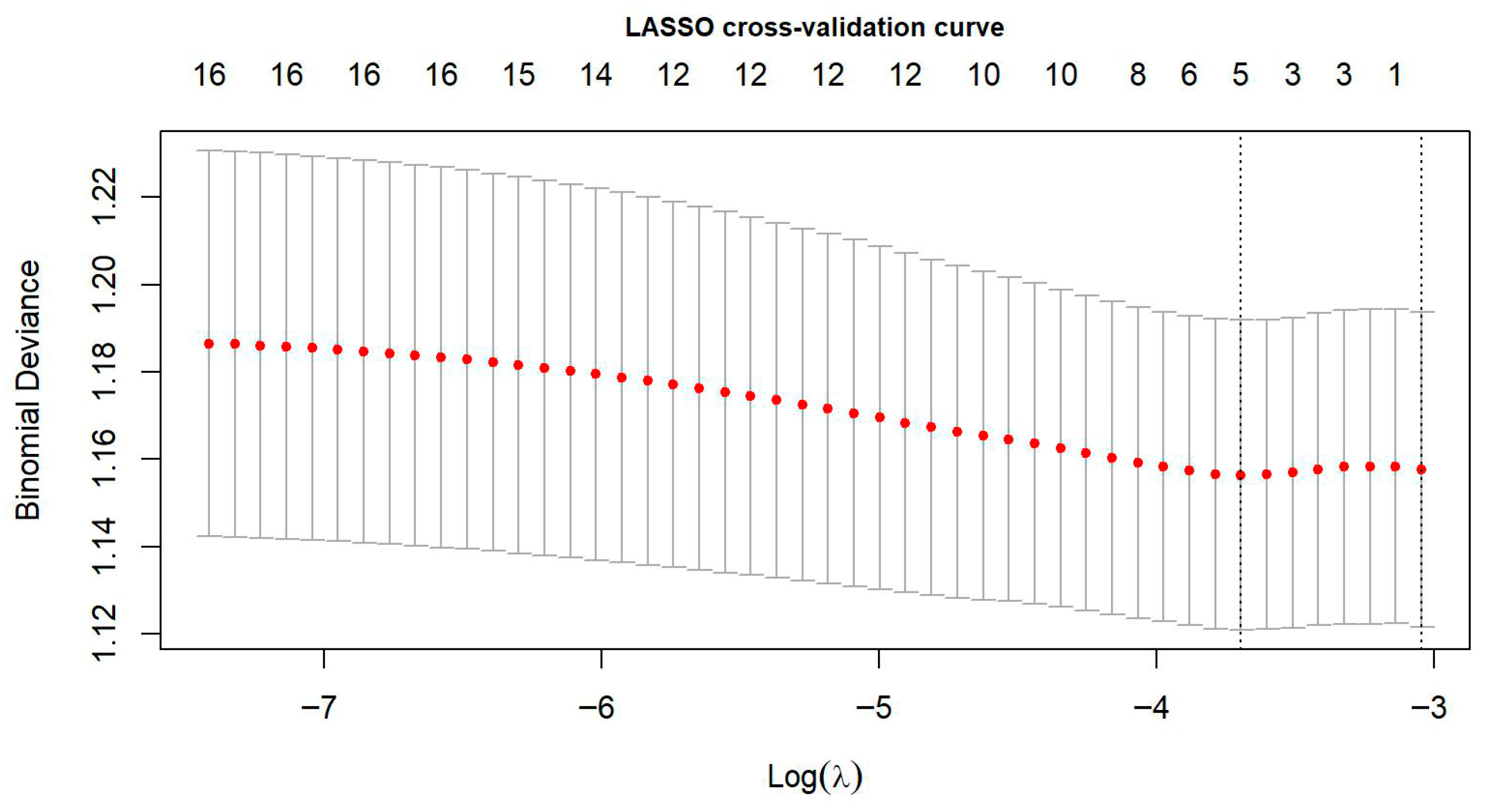

3.4. Construction and Validation of a Multidimensional Synthetic Dietary Behaviour Index (SDBI)

3.5. Moderated Mediation Analysis: The Interplay Between Dietary Behaviours, Physical Activity, and Sleep Quality

3.5.1. Path-Specific Regression Models

3.5.2. Conditional Indirect Associations

4. Discussion

4.1. Sex Differences in Sleep Quality

4.2. Dietary Patterns and Sleep Quality

4.3. Physical Activity as a Mediator Between Diet and Sleep

4.4. Moderating Effect of Sex in the Mediation Pathway

4.5. Integrative Perspective and Behavioural Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hashim, H.; Ng, J.S.; Ngo, J.X.; Ng, Y.Z.; Aravindkumar, B. Lifestyle Factors Associated with Poor Sleep Quality among Undergraduate Dental Students at a Malaysian Private University. Sleep Sci. 2022, 15, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campsen, N.A.; Buboltz, W.C. Lifestyle Factors’ Impact on Sleep of College Students. Austin J. Sleep Disord. 2017, 4, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abojedi, A.; Alsheikh Ali, A.S.; Basmaji, J. Assessing the Impact of Technology Use, Social Engagement, Emotional Regulation, and Sleep Quality among Undergraduate Students in Jordan: Examining the Mediating Effect of Perceived and Academic Stress. Health Psychol. Res. 2023, 11, 73348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, M.L.; Palmer, A.K.; Sechrist, M.F.; Abraham, S. College Students’ Sleep Habits and Their Perceptions Regarding Its Effects on Quality of Life. Int. J. Stud. Nurs. 2018, 3, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappuccio, F.P.; D’Elia, L.; Strazzullo, P.; Miller, M.A. Sleep Duration and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Sleep 2010, 33, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaulet, M.; Gómez-Abellán, P. Timing of Food Intake and Obesity: A Novel Association. Physiol. Behav. 2014, 134, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kredlow, M.A.; Capozzoli, M.C.; Hearon, B.A.; Calkins, A.W.; Otto, M.W. The Effects of Physical Activity on Sleep: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, M.R. Why Sleep Is Important for Health: A Psychoneuroimmunology Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 143–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, K.; Tasali, E.; Leproult, R.; Van Cauter, E. Effects of Poor and Short Sleep on Glucose Metabolism and Obesity Risk. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2009, 5, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, S.; Lin, L.; Austin, D.; Young, T.; Mignot, E. Short Sleep Duration Is Associated with Reduced Leptin, Elevated Ghrelin, and Increased Body Mass Index. PLoS Med. 2004, 1, e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandner, M.A. Sleep, Health, and Society. Sleep Med. Clin. 2017, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.P.; Willumsen, J.; Bull, F.; Chou, R.; Ekelund, U.; Firth, J.; Jago, R.; Ortega, F.B.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. 2020 WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour for Children and Adolescents Aged 5–17 Years: Summary of the Evidence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulis, S.; Falbová, D.; Hozáková, A.; Vorobelova, L. Sex-Specific Interrelationships of Sleeping and Nutritional Habits with Somatic Health Indicators in Young Adults. Bratisl. Med. J. 2025, 126, 2410–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Onge, M.P.; Mikic, A.; Pietrolungo, C.E. Effects of Diet on Sleep Quality. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaussent, I.; Bouyer, J.; Ancelin, M.L.; Akbaraly, T.; Pérès, K.; Ritchie, K.; Besset, A.; Dauvilliers, Y. Insomnia and Daytime Sleepiness Are Risk Factors for Depressive Symptoms in the Elderly. Sleep 2011, 34, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dashti, H.S.; Jones, S.E.; Wood, A.R.; Lane, J.M.; van Hees, V.T.; Wang, H.; Rhodes, J.A.; Song, Y.; Patel, K.; Anderson, S.G.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Genetic Loci for Self-Reported Habitual Sleep Duration Supported by Accelerometer-Derived Estimates. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katagiri, R.; Asakura, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Suga, H.; Sasaki, S. Low Intake of Vegetables, High Intake of Confectionary, and Unhealthy Eating Habits Are Associated with Poor Sleep Quality among Middle-Aged Female Japanese Workers. J. Occup. Health 2014, 56, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, C.; Skjaerven, L.H.; Guitard Sein-Echaluce, L.; Catalan-Matamoros, D. Effectiveness of Movement and Body Awareness Therapies in Patients with Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 55, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, T.; Fenton, S.; Duncan, M. Diet and sleep health: A scoping review of intervention studies in adults. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 33, 308–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolezal, B.A.; Neufeld, E.V.; Boland, D.M.; Martin, J.L.; Cooper, C.B. Interrelationship between Sleep and Exercise: A Systematic Review. Adv. Prev. Med. 2017, 2017, 1364387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banno, M.; Harada, Y.; Taniguchi, M.; Tobita, R.; Tsujimoto, H.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Kataoka, Y.; Noda, A. Exercise Can Improve Sleep Quality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buman, M.P.; Hekler, E.B.; Haskell, W.L.; Pruitt, L.; Conway, T.L.; Cain, K.L.; Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D.; King, A.C. Objective Light-Intensity Physical Activity Associations with Rated Health in Older Adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 172, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.P.; Dutil, C.; Sampasa-Kanyinga, H. Sleeping Hours: What Is the Ideal Number and How Does Age Impact This? Nat. Sci. Sleep 2018, 10, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, P.; Dong, Y.; Tan, L.; Liu, P.; Yi, Z. A Chain Mediation Model for Physical Exercise and Sleep Quality. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Cheng, X.; Yi, Z.; Deng, L.; Yang, L. To Explore the Relationship between Physical Activity and Sleep Quality of College Students Based on the Mediating Effect of Stress and Subjective Well-Being. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.; Llodio, I.; Iturricastillo, A.; Yanci, J.; Sánchez-Díaz, S.; Romaratezabala, E. Association of Physical Activity and/or Diet with Sleep Quality and Duration in Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semplonius, T.; Willoughby, T. Long-Term Links between Physical Activity and Sleep Quality. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 2418–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerriero, M.A.; Di Corrado, D.; Pollari, A.; Monteleone, A.M.; Coco, M. Relationship Between Sedentary Lifestyle, Physical Activity and Stress in University Students and Their Life Habits: A Scoping Review with PRISMA-ScR. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauter, E.; Spiegel, K.; Tasali, E.; Leproult, R. Metabolic Consequences of Sleep and Sleep Loss. Sleep Med. 2008, 9, S23–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Onge, M.P. Sleep-Obesity Relation: Underlying Mechanisms and Consequences for Treatment. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, O.M.; Chang, A.M.; Spilsbury, J.C.; Bos, T.; Emsellem, H.; Knutson, K.L. Sleep in the Modern Family: Protective Family Routines for Child and Adolescent Sleep. Sleep Health 2015, 1, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmaijer, E.S.; Nord, C.L.; Astle, D.E. Statistical Power for Cluster Analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2022, 23, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundfrom, D.J.; Shaw, D.G.; Ke, T.L. Minimum Sample Size Recommendations for Conducting Factor Analyses. Int. J. Test. 2005, 5, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrindell, W.A.; van der Ende, J. An Empirical Test of the Utility of the Observer-to-Variables Ratio in Factor and Components Analysis. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1985, 9, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, P.; Colton, T. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Heinze, G.; Schemper, M. A Solution to the Problem of Separation in Logistic Regression. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 2409–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., III; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A New Instrument for Psychiatric Practice and Research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPAQ Research Committee. Guidelines for the Data Processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. 2005. Available online: https://sites.google.com/view/ipaq/score (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Questionnaire of Eating Behaviour. 2025. Available online: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSdEKO_zdm_kGlom2Bq5Hxqun1lNJtyhcT2HHXBRj1dYah3P6w/viewform (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Wądołowska, L.; Krusińska, B. Procedura Opracowania Danych Żywieniowych z Kwestionariusza QEB. 2022. Available online: http://www.uwm.edu.pl/edu/lidiawadolowska (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Heymans, M.W.; Eekhout, I. Applied Missing Data Analysis with SPSS and R(Studio). 2019. Available online: https://bookdown.org/mwheymans/bookmi/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Austin, P.C.; White, I.R.; Lee, D.S.; van Buuren, S. Missing Data in Clinical Research: A Tutorial on Multiple Imputation. Can. J. Cardiol. 2021, 37, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator–Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haapala, E.A.; Lintu, N.; Eloranta, A.M.; Venäläinen, T.; Poikkeus, A.M.; Ahonen, T.; Lindi, V.; Lakka, T.A. Mediating Effects of Motor Performance, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, Physical Activity, and Sedentary Behaviour on the Associations of Adiposity and Other Cardiometabolic Risk Factors with Academic Achievement in Children. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 2296–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Contemporary Approaches to Assessing Mediation in Communication Research. In The SAGE Sourcebook of Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication Research; Hayes, A.F., Slater, M.D., Snyder, L.B., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymaekers, J.; Rousseeuw, P.J. Transforming Variables to Central Normality. Mach. Learn. 2021, 110, 4953–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, F.B. Stability of Two Hierarchical Grouping Techniques Case 1: Sensitivity to Data Errors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1974, 69, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, T. dendextend: An R Package for Visualizing, Adjusting and Comparing Trees of Hierarchical Clustering. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3718–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, F.C.; Yüksel, D.; de Zambotti, M. Sex Differences in Sleep. In Sleep Disorders in Women; Attarian, H., Viola-Saltzman, M., Eds.; Current Clinical Neurology; Humana: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deurveilher, S.; Rusak, B.; Semba, K. Estradiol and Progesterone Modulate Spontaneous Sleep Patterns and Recovery from Sleep Deprivation in Ovariectomized Rats. Sleep 2009, 32, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.; Ji, X.; Covington, L.; Brownlow, J. Psychological Distress as Predictors of Disturbed Sleep among College Students. Sleep 2023, 46, A284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.L.; Marques-Vidal, P. Sweet Dreams Are Not Made of This: No Association between Diet and Sleep Quality. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2023, 19, 2005–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutanto, C.N.; Wang, M.X.; Tan, D.; Kim, J.E. Association of Sleep Quality and Macronutrient Distribution: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression. Nutrients 2020, 12, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touitou, Y.; Reinberg, A.; Touitou, D. Association between Light at Night, Melatonin Secretion, Sleep Deprivation, and the Internal Clock: Health Impacts and Mechanisms of Circadian Disruption. Life Sci. 2017, 173, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosser, L.; Yates, C.; Dorrian, J.; Centofanti, S.; Heilbronn, L.; Wittert, G.; Kennaway, D.; Coates, A.M.; Gupta, C.C.; Stepien, J.M.; et al. Exploring Circadian and Meal Timing Impacts on Cortisol during Simulated Night Shifts. Sleep 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuraikat, F.M.; Wood, R.A.; Barragán, R.; St-Onge, M.P. Sleep and Diet: Mounting Evidence of a Cyclical Relationship. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2021, 41, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domaradzki, J. Congruence between Physical Activity Patterns and Dietary Patterns Inferred from Analysis of Sex Differences in Lifestyle Behaviours of Late Adolescents from Poland: Cophylogenetic Approach. Nutrients 2023, 15, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-García, R.; González-Forte, C.; Granero-Molina, J.; Melguizo-Ibáñez, E. Modulation Effect of Physical Activity on Sleep Quality and Mental Hyperactivity in Higher-Education Students. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boraita, R.J.; González-García, H.; Pérez, J.G.; Álvarez-Kurogi, L.; Tierno Cordón, J.; Castro López, R.; Arriscado Alsina, D.; Salas Sánchez, J. The Impact of Physical Activity Levels on Mental Health and Sleep Quality in University Online Students. J. Public Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pano-Rodriguez, A.; Arnau-Salvador, R.; Mayolas-Pi, C.; Hernandez-Gonzalez, V.; Legaz-Arrese, A.; Reverter-Masia, J. Physical Activity and Sleep Quality in Spanish Primary School Children: Mediation of Sex and Maturational Stage. Children 2023, 10, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Li, T. Sleep, Diet, and Exercise as Predictors of Physical Health: A Structural Equation Modeling Study in College Students. SAGE Open 2025, 15, 21582440251386694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.K.; Dimond, E.; Delmonico, M.J.; Sylvester, E.; Accetta, C.; Domos, C.; Lofgren, I.E. Healthy Sleep Leads to Improved Nutrition and Exercise in College Females. Top. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 35, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiazhi, S.; Caixia, C.; Lamei, G.; Jian, Z. The Relationship between Physical Activity and Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in College Students: A Mediating Effect of Diet. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1611906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, W.; Jin, X.; Wang, Z.; Cao, J. Network Analysis of Interrelationships among Physical Activity, Sleep Disturbances, Depression, and Anxiety in College Students. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augsburger, G.R.; Sobolewski, E.J.; Escalante, G.; Graybeal, A.J. Circadian Regulation for Optimizing Sport and Exercise Performance. Clocks Sleep 2025, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex = Males, N = 199 | Sex = Females, N = 219 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean | 95%CI | SD | Mean | 95%CI | SD | t | p | ||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Body height [cm] | 182.19 | 181.20 | 183.18 | 7.10 | 168.17 | 167.37 | 168.97 | 6.01 | 21.85 | 0.000 |

| Body weight [kg] | 79.63 | 78.25 | 81.00 | 9.87 | 60.86 | 59.65 | 62.06 | 9.04 | 20.29 | 0.000 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 23.97 | 23.62 | 24.32 | 2.47 | 21.49 | 21.12 | 21.85 | 2.71 | 9.74 | 0.000 |

| PSQI [scores] | 3.38 | 3.14 | 3.62 | 1.72 | 5.21 | 4.96 | 5.47 | 1.90 | −10.33 | 0.000 |

| Wholegrain bread [scores] | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.30 | −5.78 | 0.000 |

| Milk [scores] | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.31 | −3.07 | 0.002 |

| Fermented milk [scores] | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.23 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.23 | −8.17 | 0.000 |

| Curd cheese [scores] | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.17 | −2.54 | 0.012 |

| Fish [scores] | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.67 | 0.506 |

| Legumes [scores] | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.13 | −2.38 | 0.018 |

| Fruits [scores] | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.28 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.79 | 0.37 | −6.60 | 0.000 |

| Vegetables [scores] | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 0.32 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.38 | −8.24 | 0.000 |

| Fastfood [scores] | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 8.88 | 0.000 |

| Fried meals [scores] | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.58 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 9.93 | 0.000 |

| Yellow cheese [scores] | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 6.86 | 0.000 |

| Sweets [scores] | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.32 | −0.78 | 0.436 |

| Canned meals [scores] | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 10.63 | 0.000 |

| Sweetened beverages [scores] | 0.36 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 11.85 | 0.000 |

| Energy drinks [scores] | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 4.90 | 0.000 |

| Alcoholic drinks [scores] | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 6.32 | 0.000 |

| IPAQ [MET/minutes/week] | 3608.18 | 3418.49 | 3797.86 | 1356.88 | 3019.81 | 2886.51 | 3153.11 | 1000.89 | 5.08 | 0.000 |

| Variable | Mean Importance | Median Importance | Min Importance | Max Importance | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fastfood | 4.22 | 4.15 | 2.98 | 5.67 | Confirmed |

| fried, meals | 3.89 | 3.56 | 2.1 | 5.01 | Confirmed |

| sweetened, beverages | 3.87 | 3.54 | 2.45 | 4.98 | Confirmed |

| energy, drinks | 3.1 | 3.02 | 1.88 | 4.09 | Confirmed |

| alcoholic, drinks | 2.94 | 2.84 | 1.76 | 3.98 | Confirmed |

| canned, meals | 2.83 | 2.65 | 1.95 | 4.6 | Confirmed |

| vegetables | 2.41 | 2.32 | 1.5 | 3.05 | Confirmed |

| curd, cheese | 2.11 | 2.07 | 1.44 | 2.88 | Confirmed |

| wholegrain, bread | 1.87 | 1.83 | 1.21 | 2.36 | Confirmed |

| milk | 0.54 | 0.5 | 0.31 | 0.71 | Rejected |

| fermented, milk | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.25 | 0.66 | Rejected |

| fish | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.58 | Rejected |

| legumes | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.54 | Rejected |

| fruits | 0.31 | 0.3 | 0.16 | 0.47 | Rejected |

| yellow, cheese | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.44 | Rejected |

| sweets | 0.21 | 0.2 | 0.12 | 0.34 | Rejected |

| Variable | β (Log-Odds) | OR | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| sweetened.beverages | 0.91 | 2.49 | ↑ poor sleep |

| energy.drinks | 0.68 | 1.97 | ↑ poor sleep |

| fastfood | 0.58 | 1.79 | ↑ poor sleep |

| fried.meals | 0.49 | 1.63 | ↑ poor sleep |

| vegetables | −0.42 | 0.66 | ↓ poor sleep |

| curd.cheese | −0.29 | 0.75 | ↓ poor sleep |

| Path/Predictor | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model a: IPAQ ~ MCA + BMI + Sex | ||||

| Intercept | 0.35 | 0.07 | 5.02 | <0.001 |

| MCA (X) | −0.16 | 0.05 | −3.27 | 0.001 |

| BMI | −0.22 | 0.05 | −4.14 | <0.001 |

| Sex (W) | −0.67 | 0.10 | −6.59 | <0.001 |

| Model R2 = 0.14 | ||||

| Model b: PSQI ~ MCA + IPAQ × Sex + BMI | ||||

| Intercept | 3.02 | 0.12 | 25.21 | <0.001 |

| MCA (X) | −0.11 | 0.08 | −1.35 | 0.177 |

| IPAQ (M) | −0.20 | 0.10 | −2.05 | 0.041 |

| Sex (W) | 2.42 | 0.18 | 13.66 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 0.91 | 0.09 | 10.18 | <0.001 |

| IPAQ × Sex (M × W) | −0.45 | 0.16 | −2.78 | 0.006 |

| Model R2 = 0.44 |

| Group | Indirect Effect (β) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 0.032 | [0.003, 0.079] | 0.021 |

| Females | 0.102 | [0.023, 0.193] | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Domaradzki, J. Sex Moderates the Mediating Effect of Physical Activity in the Relationship Between Dietary Habits and Sleep Quality in University Students. Nutrients 2026, 18, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010026

Domaradzki J. Sex Moderates the Mediating Effect of Physical Activity in the Relationship Between Dietary Habits and Sleep Quality in University Students. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleDomaradzki, Jarosław. 2026. "Sex Moderates the Mediating Effect of Physical Activity in the Relationship Between Dietary Habits and Sleep Quality in University Students" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010026

APA StyleDomaradzki, J. (2026). Sex Moderates the Mediating Effect of Physical Activity in the Relationship Between Dietary Habits and Sleep Quality in University Students. Nutrients, 18(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010026