Heat-Treated Limosilactobacillus fermentum PS150 Improves Sleep Quality with Severity-Dependent Benefits: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Procedure

2.3. Subjective Psychological Inventories

2.4. Subjective and Objective Sleep Assessments

2.5. Biomarkers

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics and Baseline Performances

3.2. Efficacy of HT-PS150

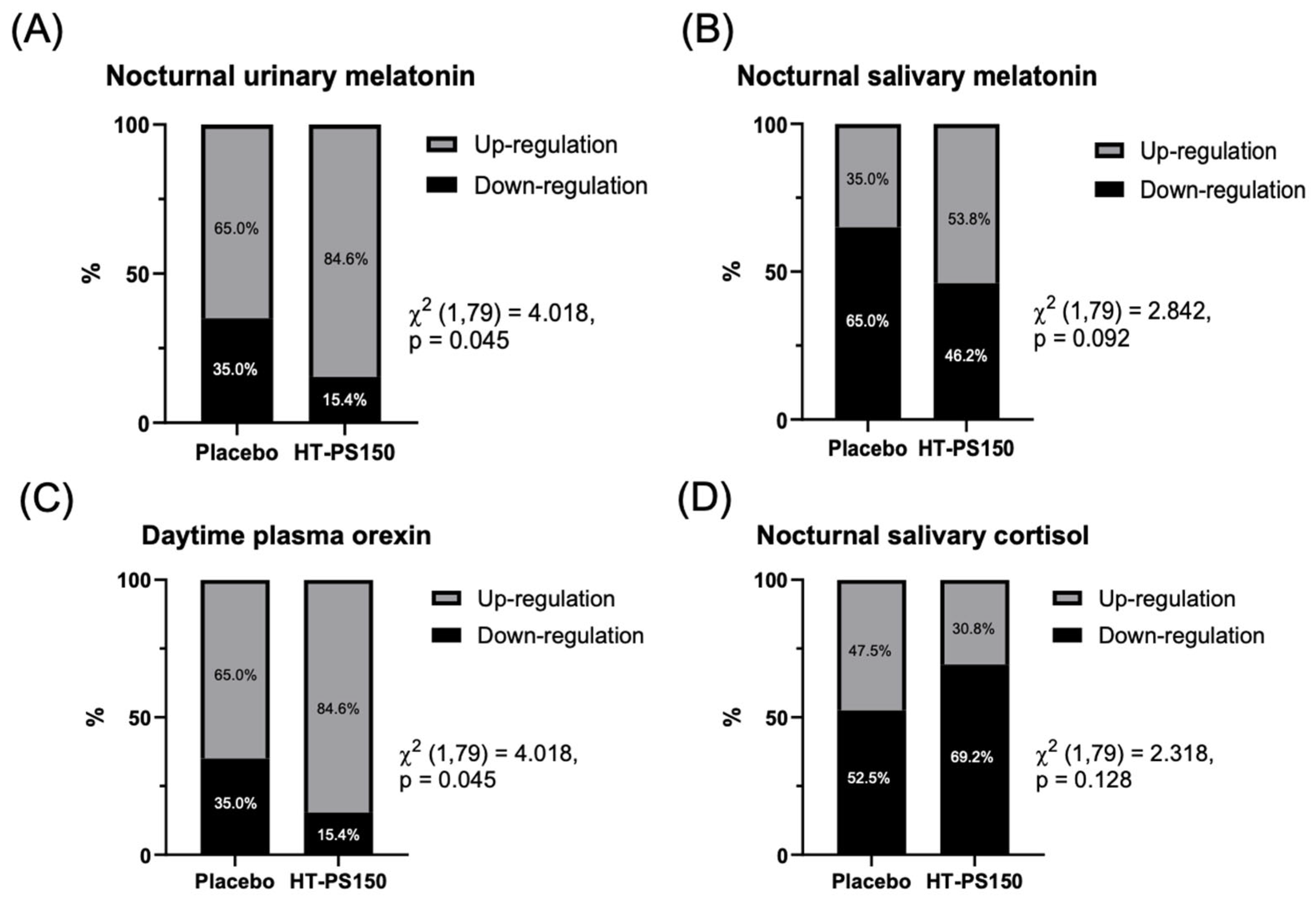

3.3. Results of Biomarker Regulation

3.4. Subgroup Results of Those with Higher Insomnia Symptoms (ISI ≥ 8)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zang, W.; Liu, N.; Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Guo, B.; Xiao, N.; Fang, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, X.; et al. From quality of life to sleep quality in Chinese college students: Stress and anxiety as sequential mediators with nonlinear effects via machine learning. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 389, 119679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, N.; Shrestha, S.L.; Sun, J.Z. Metabolic disturbances: Role of the circadian timing system and sleep. Diabetol. Int. 2017, 8, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shochat, T. Impact of lifestyle and technology developments on sleep. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 2012, 4, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Straten, A.; Weinreich, K.J.; Fábián, B.; Reesen, J.; Grigori, S.; Luik, A.I.; Harrer, M.; Lancee, J. The Prevalence of Insomnia Disorder in the General Population: A Meta-Analysis. J. Sleep Res. 2025, 34, e70089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medic, G.; Wille, M.; Hemels, M.E. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 2017, 9, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sateia, M.J.; Buysse, D.J.; Krystal, A.D.; Neubauer, D.N.; Heald, J.L. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 307–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labad, J.; Salvat-Pujol, N.; Armario, A.; Cabezas, A.; Arriba-Arnau, A.; Nadal, R.; Martorell, L.; Urretavizcaya, M.; Monreal, J.A.; Crespo, J.M.; et al. The Role of Sleep Quality, Trait Anxiety and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Measures in Cognitive Abilities of Healthy Individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 7600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.R.; Osadchiy, V.; Kalani, A.; Mayer, E.A. The Brain-Gut-Microbiome Axis. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 6, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Salinas, E.; Ortiz, G.G.; Ramirez-Jirano, L.J.; Morales, J.A.; Bitzer-Quintero, O.K. From Probiotics to Psychobiotics: Live Beneficial Bacteria Which Act on the Brain-Gut Axis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Di Ciaula, A.; Mahdi, L.; Jaber, N.; Di Palo, D.M.; Graziani, A.; Baffy, G.; Portincasa, P. Unraveling the Role of the Human Gut Microbiome in Health and Diseases. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhanna, A.; Martini, N.; Hmaydoosh, G.; Hamwi, G.; Jarjanazi, M.; Zaifah, G.; Kazzazo, R.; Haji Mohamad, A.; Alshehabi, Z. The correlation between gut microbiota and both neurotransmitters and mental disorders: A narrative review. Medicine 2024, 103, e37114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xie, P. Gut microbiota and its metabolites in depression: From pathogenesis to treatment. eBioMedicine 2023, 90, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.-G.; Li, J.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, D.-D.; Wu, S.-X.; Huang, S.-Y.; Saimaiti, A.; Yang, Z.-J.; Gan, R.-Y.; Li, H.-B. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Anxiety, Depression, and Other Mental Disorders as Well as the Protective Effects of Dietary Components. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Pan, W.; Diao, J.; Sun, L.; Meng, M. Gut microbiota variations in depression and anxiety: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, Y.P.; Bernardi, A.; Frozza, R.L. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Jiang, T.; Chen, M.; Ji, X.; Wang, Y. Gut microbiota and sleep: Interaction mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Open Life Sci. 2024, 19, 20220910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Fang, D.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Sleep Deprivation and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Current Understandings and Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oroojzadeh, P.; Bostanabad, S.Y.; Lotfi, H. Psychobiotics: The Influence of Gut Microbiota on the Gut-Brain Axis in Neurological Disorders. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 72, 1952–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.-H.; Liu, Y.-W.; Wu, C.-C.; Wang, S.; Tsai, Y.-C. Psychobiotics in mental health, neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders. J. Food Drug Anal. 2019, 27, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Toro-Barbosa, M.; Hurtado-Romero, A.; Garcia-Amezquita, L.E.; Garcia-Cayuela, T. Psychobiotics: Mechanisms of Action, Evaluation Methods and Effectiveness in Applications with Food Products. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, M.; Nishida, K.; Gondo, Y.; Kikuchi-Hayakawa, H.; Ishikawa, H.; Suda, K.; Kawai, M.; Hoshi, R.; Kuwano, Y.; Miyazaki, K.; et al. Beneficial effects of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on academic stress-induced sleep disturbance in healthy adults: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Benef. Microbes 2017, 8, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, D.; Kawai, T.; Nishida, K.; Kuwano, Y.; Fujiwara, S.; Rokutan, K. Daily intake of Lactobacillus gasseri CP2305 improves mental, physical, and sleep quality among Japanese medical students enrolled in a cadaver dissection course. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 31, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Tomura, Y.; Kitagawa, Y.; Nakashima, T.; Kobanawa, S.; Uki, K.; Oshida, J.; Kodama, T.; Fukui, S.; Kobayashi, D. Effects of probiotics on sleep parameters: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 63, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Lu, S.; Tan, K.; Jiang, P.; Liu, P.; Peng, Q. Impact of probiotics on sleep quality and mood states in patients with insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1596990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, K.; Shukla, N.; Naik, S.; Sambhav, K.; Dange, K.; Bhuyan, D.; Imranul Haq, Q.M. The Bidirectional Relationship Between the Gut Microbiome and Mental Health: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e80810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Fang, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Fan, R.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; et al. Psychobiotic Lactobacillus plantarum JYLP-326 relieves anxiety, depression, and insomnia symptoms in test anxious college via modulating the gut microbiota and its metabolism. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1158137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanihiro, R.; Yuki, M.; Sasai, M.; Haseda, A.; Kagami-Katsuyama, H.; Hirota, T.; Honma, N.; Nishihira, J. Effects of Prebiotic Yeast Mannan on Gut Health and Sleep Quality in Healthy Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.F.; Li, M.; Han, X.; Fan, Y.T.; Yang, J.J.; Long, Y.; Yu, J.; Ji, H.Y. Lactobacilli-Mediated Regulation of the Microbial-Immune Axis: A Review of Key Mechanisms, Influencing Factors, and Application Prospects. Foods 2025, 14, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pique, N.; Berlanga, M.; Minana-Galbis, D. Health Benefits of Heat-Killed (Tyndallized) Probiotics: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, F.C.; Lan, C.C.; Huang, T.Y.; Chen, K.W.; Chai, C.Y.; Chen, W.T.; Fang, A.H.; Chen, Y.H.; Wu, C.S. Heat-killed and live Lactobacillus reuteri GMNL-263 exhibit similar effects on improving metabolic functions in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 2374–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, A.; Shih, C.-T.; Huang, C.-L.; Wu, C.-C.; Lin, C.-T.; Tsai, Y.-C. Hypnotic Effects of Lactobacillus fermentum PS150TM on Pentobarbital-Induced Sleep in Mice. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Shih, C.T.; Chu, H.F.; Chen, C.W.; Cheng, Y.T.; Wu, C.C.; Yang, C.C.H.; Tsai, Y.C. Lactobacillus fermentum PS150 promotes non-rapid eye movement sleep in the first night effect of mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., III; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, P.-S.; Wang, S.-Y.; Wang, M.-Y.; Su, C.-T.; Yang, T.-T.; Huang, C.-J.; Fang, S.-C. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) in primary insomnia and control subjects. Qual. Life Res. 2005, 14, 1943–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastien, C.H.; Vallières, A.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep. Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.M.; Belleville, G.; Bélanger, L.; Ivers, H. The Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011, 34, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-M.; Hsu, S.-C.; Lin, S.-C.; Chou, Y.; Chen, Y. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of insomnia severity index. Arch. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 4, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-I.; Yeh, Z.-T.; Huang, H.-C.; Sun, F.-J.; Tjung, J.-J.; Hwang, L.-C.; Shih, Y.-H.; Yeh, A.W.-C. Validation of Patient Health Questionnaire for depression screening among primary care patients in Taiwan. Compr. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-T.; Liu, S.-I.; Huang, H.-C.; Sun, F.-J.; Huang, C.-R.; Yeung, A. Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the Short Form of Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q-SF). Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevanovic, D. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire–short form for quality of life assessments in clinical practice: A psychometric study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 18, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, L.; Guillou, S.; Durand, H. Probiotic food supplement reduces stress-induced gastrointestinal symptoms in volunteers: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Nutr. Res. 2008, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-I.; Wu, C.-C.; Tsai, P.-J.; Cheng, L.-H.; Hsu, C.-C.; Shan, I.-K.; Chan, P.-Y.; Lin, T.-W.; Ko, C.-J.; Chen, W.-L. Psychobiotic supplementation of PS128TM improves stress, anxiety, and insomnia in highly stressed information technology specialists: A pilot study. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 614105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M.; Ohlsson, B.; Ulander, K. Development and psychometric testing of the Visual Analogue Scale for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (VAS-IBS). BMC Gastroenterol. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, H.; Bolton, J. Assessing the clinical significance of change scores recorded on subjective outcome measures. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2004, 27, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghayegh, S.; Khoshnevis, S.; Smolensky, M.H.; Diller, K.R.; Castriotta, R.J. Performance assessment of new-generation Fitbit technology in deriving sleep parameters and stages. Chronobiol. Int. 2020, 37, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghayegh, S.; Khoshnevis, S.; Smolensky, M.H.; Diller, K.R.; Castriotta, R.J. Accuracy of wristband Fitbit models in assessing sleep: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e16273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.E.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, S.W.; Bae, K.-H.; Baek, Y.H. Validation of Fitbit Inspire 2TM Against Polysomnography in Adults Considering Adaptation for Use. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 2023, 15, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmbach, D.A.; Anderson, J.R.; Drake, C.L. The impact of stress on sleep: Pathogenic sleep reactivity as a vulnerability to insomnia and circadian disorders. J. Sleep Res. 2018, 27, e12710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndych, A.; El-Abassi, R.; Mader, E.C., Jr. The Role of Sleep and the Effects of Sleep Loss on Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Processes. Cureus 2025, 17, e84232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voultsios, A.; Kennaway, D.J.; Dawson, D. Salivary Melatonin as a Circadian Phase Marker: Validation and Comparison to Plasma Melatonin. J. Biol. Rhythm. 1997, 12, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benloucif, S.; Burgess, H.J.; Klerman, E.B.; Lewy, A.J.; Middleton, B.; Murphy, P.J.; Parry, B.L.; Revell, V.L. Measuring Melatonin in Humans. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2008, 4, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challet, E.; Pévet, P. Melatonin in energy control: Circadian time-giver and homeostatic monitor. J. Pineal Res. 2024, 76, e12961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, T.M.; Schatzberg, A.F. On the interactions of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and sleep: Normal HPA axis activity and circadian rhythm, exemplary sleep disorders. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 3106–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieda, M. The roles of orexins in sleep/wake regulation. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 118, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crasson, M.; Kjiri, S.; Colin, A.; Kjiri, K.; L’Hermite-Baleriaux, M.; Ansseau, M.; Legros, J.J. Serum melatonin and urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin in major depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, Y.; Tung, N.Y.C.; Shen, L.; Bei, B.; Phillips, A.; Wiley, J.F. Daily associations between salivary cortisol and electroencephalographic-assessed sleep: A 15-day intensive longitudinal study. Sleep 2024, 47, zsae087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, K.A.; Karhu, T.; Jurado Acosta, A.; Vakkuri, O.; Leppäluoto, J.; Herzig, K.-H. Plasma Orexin-A Levels Do Not Undergo Circadian Rhythm in Young Healthy Male Subjects. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teame, T.; Wang, A.; Xie, M.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Ding, Q.; Gao, C.; Olsen, R.E.; Ran, C.; Zhou, Z. Paraprobiotics and Postbiotics of Probiotic Lactobacilli, Their Positive Effects on the Host and Action Mechanisms: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 570344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Sahota, P.; Thakkar, M.M. Melatonin promotes sleep in mice by inhibiting orexin neurons in the perifornical lateral hypothalamus. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 65, e12498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.R. Sleep disruption induces activation of inflammation and heightens risk for infectious disease: Role of impairments in thermoregulation and elevated ambient temperature. Temperature 2023, 10, 198–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, C.; McCartney, D.; Desbrow, B.; Khalesi, S. Effects of probiotics and paraprobiotics on subjective and objective sleep metrics: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 1536–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Wang, K.Y.; Wang, N.R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.P. Effect of probiotics and paraprobiotics on patients with sleep disorders and sub-healthy sleep conditions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1477533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, A.K.D.; van Waarde, A.; Willemsen, A.T.M.; Bosker, F.J.; Luiten, P.G.M.; den Boer, J.A.; Kema, I.P.; Dierckx, R.A.J.O. Measuring serotonin synthesis: From conventional methods to PET tracers and their (pre)clinical implications. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2011, 38, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbank, E.; Lopez, M. Orexins/Hypocretins: Key Regulators of Energy Homeostasis. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-L.; Chu, H.-F.; Wu, C.-C.; Deng, F.-S.; Wen, P.-J.; Chien, S.-P.; Chao, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-T.; Lu, M.-K.; Tsai, Y.-C. Exopolysaccharide is the potential effector of Lactobacillus fermentum PS150, a hypnotic psychobiotic strain. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1209067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Placebo | HT-PS150 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | ||

| Sex | 0.926 | ||

| Male | 16 (40.0%) | 16 (41.0%) | |

| Female | 24 (60.0%) | 23 (59.0%) | |

| Marital status | 0.504 | ||

| Single | 25 (62.5%) | 18 (46.2%) | |

| Cohabit | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Married | 12 (30.0%) | 17 (43.6%) | |

| Separated | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Divorced | 1 (2.5%) | 2 (5.1%) | |

| Widowed | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Children | 0.314 | ||

| With | 16 (40.0%) | 20 (51.2%) | |

| Without | 24 (60.0%) | 19 (48.8%) | |

| Other supplements | 0.391 | ||

| With | 16 (40.0%) | 12 (30.8%) | |

| Without | 24 (60.0%) | 27 (69.2%) | |

| Age | 34.1 (11.4) | 36.3 (11.1) | 0.380 |

| Education | 16.2 (1.8) | 16.5 (1.7) | 0.466 |

| BMI | 23.9 (3.7) | 23.9 (4.1) | 0.973 |

| PSQI Global | 7.6 (2.2) | 7.7 (2.8) | 0.837 |

| ISI Total | 8.4 (4.0) | 7.6 (3.8) | 0.372 |

| Variables | V1 | V2 | Group | Time | Group*Time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | HT-PS150 | Placebo | HT-PS150 | |||||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | β [95% CI] | p | β [95% CI] | p | β [95% CI] | p | |

| PSQI Global | 7.7 (3.2) | 7.6 (3.1) | 6.5 (2.8) | 6.4 (2.8) | −0.110 [−1.490, 1.269] | 0.876 | −1.250 [−2.147, −0.353] | 0.006 | 0.071 [−1.317, 1.458] | 0.921 |

| ISI Total | 9.3 (4.7) | 8.9 (4.1) | 6.4 (4.5) | 6.4 (4.7) | −0.326 [−2.251, 1.599] | 0.740 | −2.875 [−4.409, −1.341] | <0.001 | 0.285 [−1.855, 2.425] | 0.794 |

| GAD-7 Total | 5.1 (4.1) | 5.5 (3.1) | 4.4 (4.3) | 3.6 (2.8) | 0.412 [−1.172, 1.995] | 0.610 | −0.625 [−1.616, 0.366] | 0.217 | −1.196 [−2.563, 0.172] | 0.087 |

| PHQ-9 Total | 5.5 (4.1) | 5.6 (3.4) | 4.0 (4.3) | 4.2 (2.9) | 0.141 [−1.500, 1.782] | 0.866 | −1.475 [−2.632, −0.318] | 0.012 | 0.013 [−1.555, 1.582] | 0.987 |

| QLESQ-SF Total | 51.0 (8.1) | 48.8 (6.2) | 52.4 (8.4) | 50.2 (5.7) | −2.154 [5.288, 0.979] | 0.178 | 1.450 [−0.592, 3.492] | 0.164 | −0.117 [−3.281, 3.048] | 0.942 |

| VAS-GI Total | 11.1 (9.7) | 12.7 (10.4) | 9.1 (9.5) | 12.1 (11.1) | 1.669 [−2.706, 6.044] | 0.455 | −2.025 [−4.787, 0.737] | 0.151 | 1.333 [−2.917, 5.582] | 0.539 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, M.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-Y.; Huang, C.-C. Heat-Treated Limosilactobacillus fermentum PS150 Improves Sleep Quality with Severity-Dependent Benefits: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2026, 18, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010014

Lee M-C, Chen C-Y, Chen C-Y, Huang C-C. Heat-Treated Limosilactobacillus fermentum PS150 Improves Sleep Quality with Severity-Dependent Benefits: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Mon-Chien, Chao-Yuan Chen, Ching-Yun Chen, and Chi-Chang Huang. 2026. "Heat-Treated Limosilactobacillus fermentum PS150 Improves Sleep Quality with Severity-Dependent Benefits: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010014

APA StyleLee, M.-C., Chen, C.-Y., Chen, C.-Y., & Huang, C.-C. (2026). Heat-Treated Limosilactobacillus fermentum PS150 Improves Sleep Quality with Severity-Dependent Benefits: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients, 18(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010014