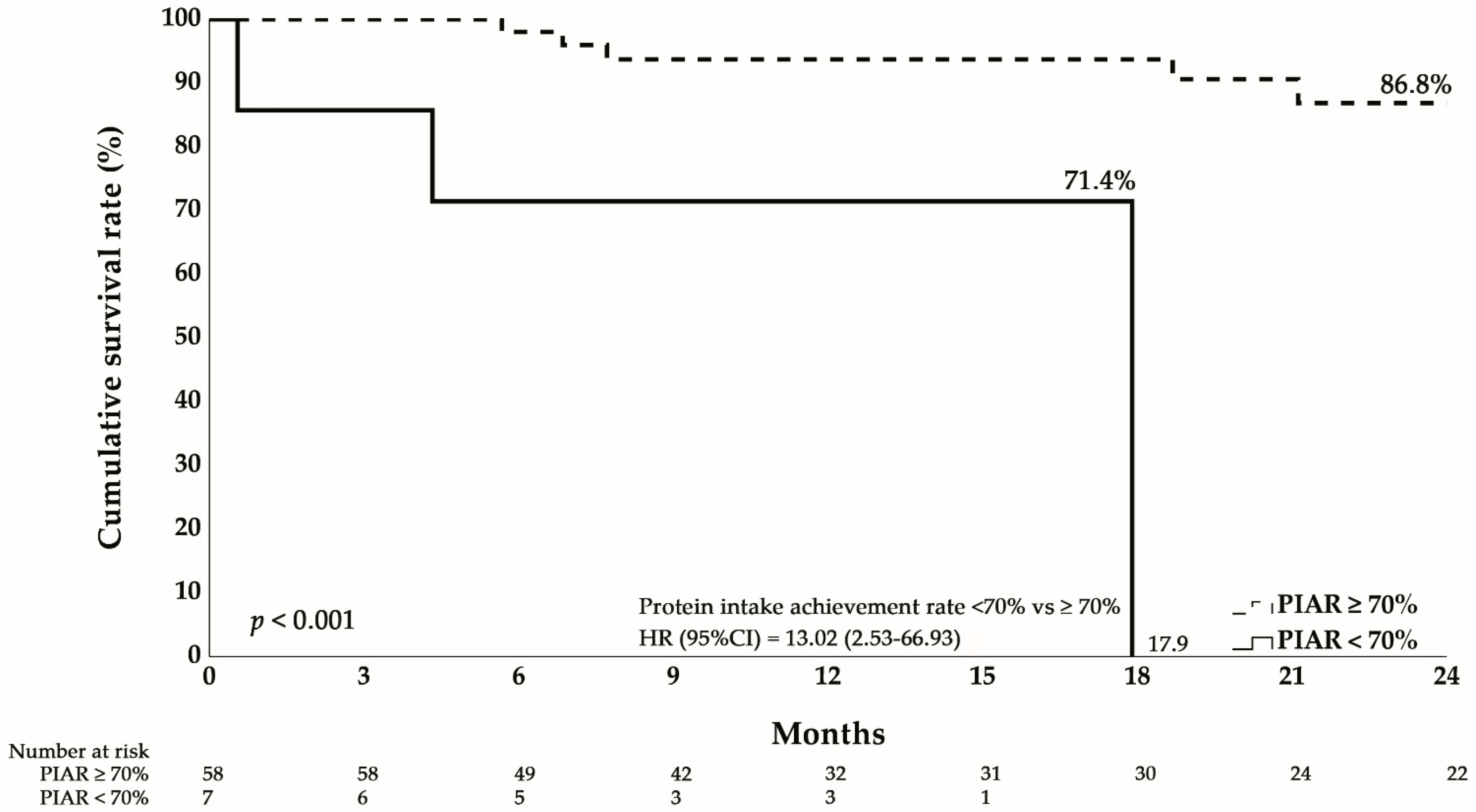

Failure to Achieve 70% of Recommended Protein Intake at One Year Predicts 13-Fold Higher Mortality After Gastrectomy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

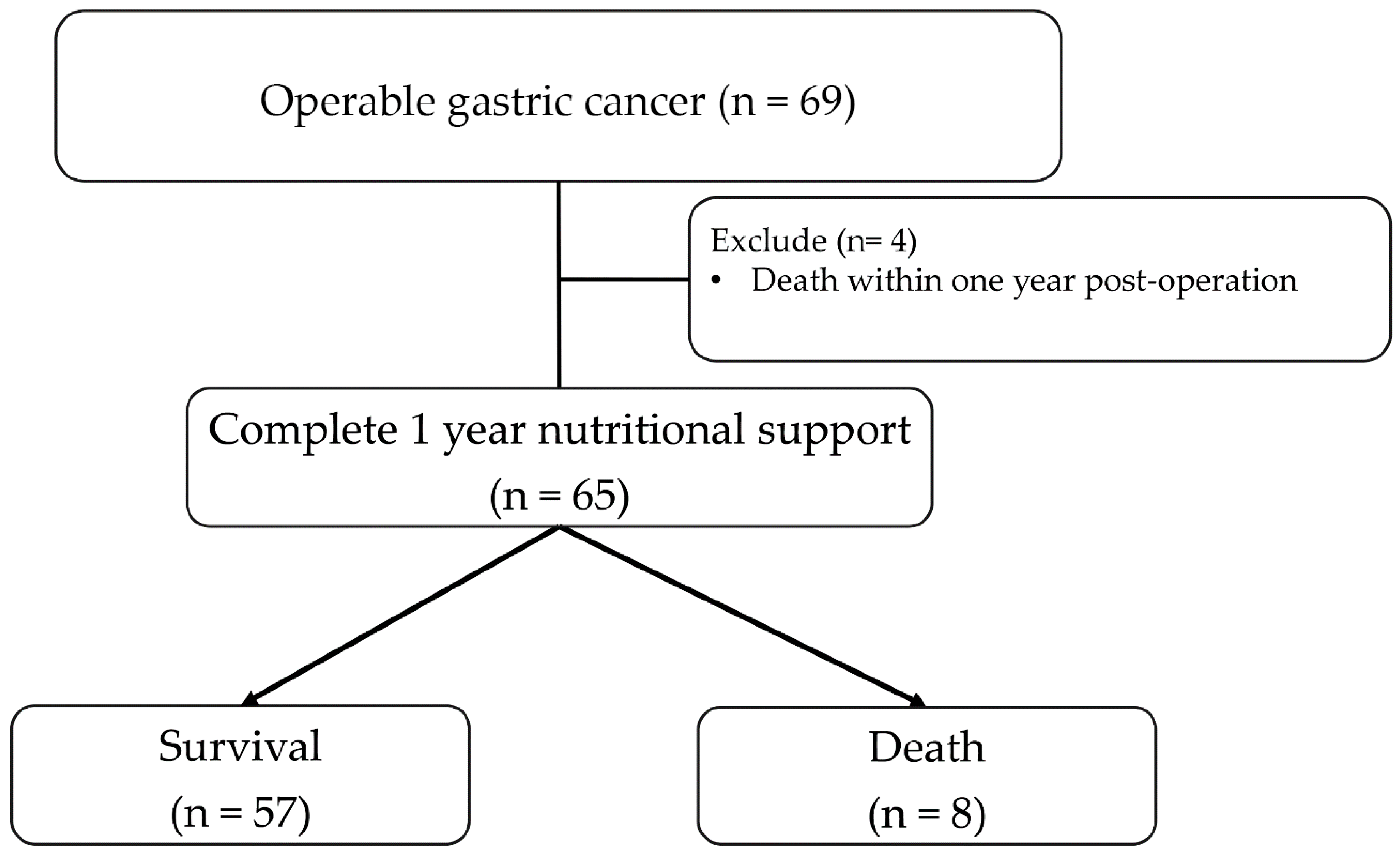

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Study Procedures and Follow-Up

2.3. Nutritional Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Nutritional Changes from Baseline to One Year

3.3. Survival Outcomes

3.4. Factors Associated with Inadequate Protein Intake

3.5. Impact of Protein Intake on Survival

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Zheng, R.; Zeng, H.; Wang, S.; Sun, K.; Chen, R.; Li, L.; Wei, W.; He, J. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 2024, 4, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2021 (6th edition). Gastric. Cancer 2023, 26, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.-T.; Lin, Y.-N.; Chen, Y.-F.; Kou, H.-W.; Wang, S.-Y.; Chou, W.-C.; Wu, T.-R.; Yeh, T.-S. A comprehensive overview of gastric cancer management from a surgical point of view. Biomed. J. 2025, 48, 100817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzetti, F. Nutritional support of the oncology patient. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2013, 87, 172–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grochowska, E.; Gazi, A.; Surwiłło-Snarska, A.; Kapała, A. Nutritional problems of patients after gastrectomy and the risk of malnutrition. Nowotw. J. Oncol. 2024, 74, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanshan, W.; Lian, W.; Lu, D.; Liping, L.; Peipei, L.; Juanli, Z. Best practices for home nutritional management in postoperative gastric cancer patients: An evidence summary. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, S.; Akiyama, H.; Tanabe, M.; Nakayama, Y.; Onuma, S.; Morita, J.; Hashimoto, I.; Suematsu, H.; Nakazono, M.; Yamada, T.; et al. Breakfast Protein Intake of One-third of Daily Requirement Can Maintain Lean Body Mass Post-distal Gastrectomy. In Vivo 2024, 38, 2897–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.K.; Lee, H.J. Impact of malnutrition and nutritional support after gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2024, 8, 534–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyama, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Shirai, J.; Hayashi, T.; Yamada, T.; Tsuchida, K.; Hasegawa, S.; Cho, H.; Yukawa, N.; Oshima, T.; et al. Body weight loss after surgery is an independent risk factor for continuation of S-1 adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 20, 2000–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Hirao, M.; Nishikawa, K.; Maeda, S.; Haraguchi, N.; Miyake, M.; Hama, N.; Miyamoto, A.; Ikeda, M.; et al. Prevalence of malnutrition among gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy and optimal preoperative nutritional support for preventing surgical site infections. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, S778–S785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Fearon, K.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimann, A.; Braga, M.; Carli, F.; Higashiguchi, T.; Hübner, M.; Klek, S.; Laviano, A.; Ljungqvist, O.; Lobo, D.N.; Martindale, R.G.; et al. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4745–4761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutière, M.; Cottet-Rousselle, C.; Coppard, C.; Couturier, K.; Féart, C.; Couchet, M.; Corne, C.; Moinard, C.; Breuillard, C. Protein intake in cancer: Does it improve nutritional status and/or modify tumour response to chemotherapy? J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 2003–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, P.; Blaser, A.R.; Berger, M.M.; Calder, P.C.; Casaer, M.; Hiesmayr, M.; Mayer, K.; Montejo-Gonzalez, J.C.; Pichard, C.; Preiser, J.-C.; et al. ESPEN practical and partially revised guideline: Clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1671–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H.; Lee, S.; Song, J.H.; Choi, S.; Cho, M.; Kwon, I.G.; Son, T.; Kim, H.-I.; Cheong, J.-H.; Hyung, W.J.; et al. Prognostic significance of body mass index and prognostic nutritional index in stage II/III gastric cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migita, K.; Takayama, T.; Saeki, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Wakatsuki, K.; Enomoto, K.; Tanaka, T.; Ito, M.; Kurumatani, N.; Nakajima, Y. The prognostic nutritional index predicts long-term outcomes of gastric cancer patients independent of tumor stage. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 20, 2647–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, X.; Liu, J.; Kong, P.; Chen, S.; Zhan, Y.; Xu, D. Preoperative C-reactive protein/albumin ratio predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for gastric cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2015, 8, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chen, X.; Chen, G.; Zhao, Z.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, F.; Lin, J.; Nie, R.; Chen, Y. Combined Use of Tumor Markers in Gastric Cancer: A Novel Method with Promising Prognostic Accuracy and Practicality. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 8561–8571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cong, M.; Cui, J.; Xu, H.; Chen, J.; Li, T.; Li, Z.; Liu, M.; Li, W.; Guo, Z.L.; et al. Chinese Society of Nutritional Oncology (CSNO). General rules for treating cancer-related malnutrition. Precis. Nutr. 2022, 1, e00024. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L.; Senesse, P.; Gioulbasanis, I.; Antoun, S.; Bozzetti, F.; Deans, C.; Strasser, F.; Thoresen, L.; Jagoe, R.T.; Chasen, M.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for the classification of cancer-associated weight loss. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, K.; Strasser, F.; Anker, S.D.; Bosaeus, I.; Bruera, E.; Fainsinger, R.L.; Jatoi, A.; Loprinzi, C.; MacDonald, N.; Mantovani, G.; et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, E.A.; Ibiebele, T.I.; Friedlander, M.L.; Grant, P.T.; van der Pols, J.C.; Webb, P.M. Association of Protein Intake with Recurrence and Survival Following Primary Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 118, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.L.; Ripley, R.T. Postgastrectomy syndromes and nutritional considerations following gastric surgery. Surg. Clin. North Am. 2017, 97, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.M.; Park, J.W.; Yang, H.K.; Kim, J.P. Nutritional status of gastric cancer patients after total gastrectomy. World J. Surg. 1998, 22, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akad, F.; Stan, C.I.; Zugun-Eloae, F.; Peiu, S.N.; Akad, N.; Crauciuc, D.-V.; Moraru, M.C.; Popa, C.G.; Gavril, L.-C.; Sufaru, R.-F.; et al. Nutritional and Biochemical Outcomes After Total Versus Subtotal Gastrectomy: Insights into Early Postoperative Prognosis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyama, T.; Sato, T.; Maezawa, Y.; Kano, K.; Hayashi, T.; Yamada, T.; Yukawa, N.; Oshima, T.; Rino, Y.; Masuda, M.; et al. Postoperative weight loss leads to poor survival through poor S-1 efficacy in patients with stage II/III gastric cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 22, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molfino, A.; Emerenziani, S.; Tonini, G.; Santini, D.; Gigante, A.; Guarino, M.P.L.; Nuglio, C.; Imbimbo, G.; La Cesa, A.; Cicala, M.; et al. Early impairment of food intake in patients newly diagnosed with cancer. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 997813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climent, M.; Munarriz, M.; Blazeby, J.; Dorcaratto, D.; Ramón, J.; Carrera, M.; Fontane, L.; Grande, L.; Pera, M. Weight loss and quality of life in patients surviving 2 years after gastric cancer resection. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 43, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, C.H.; Park, K.B.; Kim, S.; Seo, H.S.; Song, K.Y.; Lee, H.H. Predictive model for long-term weight recovery after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: An introduction to a web calculator. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (n = 65) | |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 62 (56–68) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 28 (43.1%) |

| Male | 37 (56.9%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.8 (21.6–27.8) |

| Gastrectomy, n (%) | |

| Total | 16 (24.6%) |

| Subtotal | 49 (75.4%) |

| Stage, n (%) | |

| Stage I&II | 36 (55.4%) |

| Stage III&IV | 29 (44.6%) |

| Preoperative, median (IQR) | |

| Energy intake/weight (kal/kg) | 25.4 (22.2–28.8) |

| Protein intake/weight (g/kg) | 1 (0.9–1.2) |

| Energy intake achievement rate (%) | 95.9 (84.9–102.6) |

| Protein intake achievement rate (%) | 89.2 (73.2–105) |

| Energy intake achievement rate < 70%, n (%) | 7 (10.8%) |

| Protein intake achievement rate < 70%, n (%) | 11 (16.9%) |

| Lab data (Preoperative), median (IQR) | |

| Alb (g/dL) | 4 (3.7–4.3) |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.4 (10.3–14.3) |

| Fe (μg/dL) | 54 (32–71) |

| TIBC (μg/dL) | 328 (281–370) |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 70.2 (21.9–158.7) |

| RBC folate (ng/mL) | 927.7 (795.3–1113.9) |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.1 (0.1–0.3) |

| B12 (pg/mL) | 440 (340–863) |

| Death, n (%) | 8 (12.3%) |

| Follow-up time (year), median (IQR) | 2.1 (1.6–3.2) |

| Alive (n = 57) | Death (n = 8) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 61 (54–68) | 66 (62–77) | 0.089 |

| Sex, n (%) | 1.000 | ||

| Female | 25 (43.9%) | 3 (37.5%) | |

| Male | 32 (56.1%) | 5 (62.5%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.8 (20.1–25.5) | 21.2 (19.9–23.1) | 0.299 |

| Gastrectomy, n (%) | 0.395 | ||

| Total | 13 (22.8%) | 3 (37.5%) | |

| Subtotal | 44 (77.2%) | 5 (62.5%) | |

| Stage, n (%) | 0.125 | ||

| Stage I&II | 34 (59.65%) | 2 (25.0%) | |

| Stage III&IV | 23 (40.35%) | 6 (75.0%) | |

| Postoperative 12-month, median (IQR) | |||

| Energy intake/weight (kal/kg) | 28.9 (25.7–32.1) | 26.2 (19.1–31.1) | 0.263 |

| Protein intake/weight (g/kg) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.148 |

| Energy intake achievement rate (%) | 99.6 (90.3–108.3) | 89.5 (69.4–103.9) | 0.129 |

| Protein intake achievement rate (%) | 97.5 (86.3–105.1) | 83.4 (65.3–101.0) | 0.090 |

| Energy intake achievement rate < 70%, n (%) | 5 (8.8%) | 2 (25.0%) | 0.203 |

| Protein intake achievement rate < 70%, n (%) | 4 (7.0%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0.035 * |

| Lab data (Preoperative), median (IQR) | |||

| Alb (g/dL) | 4.1 (3.7–4.3) | 3.7 (3.5–3.9) | 0.041 * |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.6 (10.4–14.3) | 10.4 (8.6–14) | 0.212 |

| Fe (μg/dL) | 56 (34–76.5) | 45 (29.3–68.8) | 0.677 |

| TIBC (μg/dL) | 329 (278.5–370) | 317 (283.5–371.8) | 0.898 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 71.8 (21.9–182.9) | 55.9 (23.2–149.7) | 0.665 |

| RBC folate (ng/mL) | 927.7 (792.4–1113.9) | 957.6 (829.4–1339.3) | 0.842 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.1 (0.1–0.3) | 0.1 (0.1–0.2) | 0.825 |

| B12 (pg/mL) | 457 (346.8–923) | 379.5 (327–497.5) | 0.247 |

| Protein ≥ 70% (n = 58) | Protein < 70% (n = 7) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 62 (56–68) | 62 (47–71) | 0.882 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.224 | ||

| Female | 23 (39.7%) | 5 (71.4%) | |

| Male | 35 (60.3%) | 2 (28.6%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.8 (21.5–27.3) | 28.3 (23.9–31.7) | 0.079 |

| Gastrectomy, n (%) | 0.00796 | ||

| Total | 11 (19%) | 5 (71.4%) | |

| Subtotal | 47 (81%) | 2 (28.6%) | |

| Stage, n (%) | 0.0388 | ||

| Stage I&II | 35 (60.3%) | 1 (14.3%) | |

| Stage III&IV | 23 (39.7%) | 6 (85.7%) | |

| Protein intake/weight (g/kg) | 1 (0.9–1.2) | 1 (0.7–1.2) | 0.397 |

| Lab data (Preoperative), median (IQR) | |||

| Alb (g/dL) | 4 (3.7–4.2) | 4 (3.6–4.3) | 0.915 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.5 (10.4–14.3) | 10.9 (9.5–14.6) | 0.539 |

| Fe (μg/dL) | 53 (33–70) | 62 (26–97) | 0.790 |

| TIBC (μg/dL) | 328 (277–371) | 330 (306–360.5) | 0.649 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 70.3 (24.5–191) | 70.2 (17.5–122.7) | 0.570 |

| RBC folate (ng/mL) | 910.4 (791.8–1098.6) | 1106.2 (909.1–1288.7) | 0.115 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.1 (0.1–0.2) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.077 |

| B12 (pg/mL) | 436 (333.5–849.5) | 524 (362–954) | 0.572 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lin, J.-H.; Luo, S.-C.; Liu, L.-C.; Wang, Y.-L.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Fu, P.-K. Failure to Achieve 70% of Recommended Protein Intake at One Year Predicts 13-Fold Higher Mortality After Gastrectomy. Nutrients 2026, 18, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010120

Lin J-H, Luo S-C, Liu L-C, Wang Y-L, Hsu C-Y, Fu P-K. Failure to Achieve 70% of Recommended Protein Intake at One Year Predicts 13-Fold Higher Mortality After Gastrectomy. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010120

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Jou-Huai, Shao-Ciao Luo, Li-Chun Liu, Ya-Ling Wang, Chiann-Yi Hsu, and Pin-Kuei Fu. 2026. "Failure to Achieve 70% of Recommended Protein Intake at One Year Predicts 13-Fold Higher Mortality After Gastrectomy" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010120

APA StyleLin, J.-H., Luo, S.-C., Liu, L.-C., Wang, Y.-L., Hsu, C.-Y., & Fu, P.-K. (2026). Failure to Achieve 70% of Recommended Protein Intake at One Year Predicts 13-Fold Higher Mortality After Gastrectomy. Nutrients, 18(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010120