Landscape of Herbal Food Supplements: Where Do We Stand with Health Claims?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Regulatory Framework for Food Supplements

1.2. Consumer Information Regulatory Framework

1.3. Existing Knowledge and Research Gap

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Herbal Food Supplement Collection

2.2. Evaluation of Regulatory Compliance of Health Claims/Statements

- Whether the labels included the mandatory statements related to the importance of varied diet and a healthy lifestyle and compliance with recommended doses, as well as necessary precautionary and warning statements which shall follow the health claims on the labels according to Directive 2002/46/EC [11] and Regulation 1924/2006 [18].

3. Results

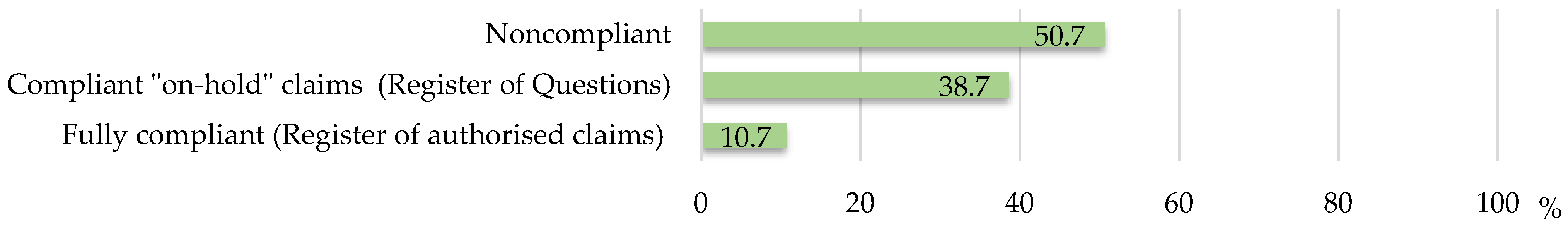

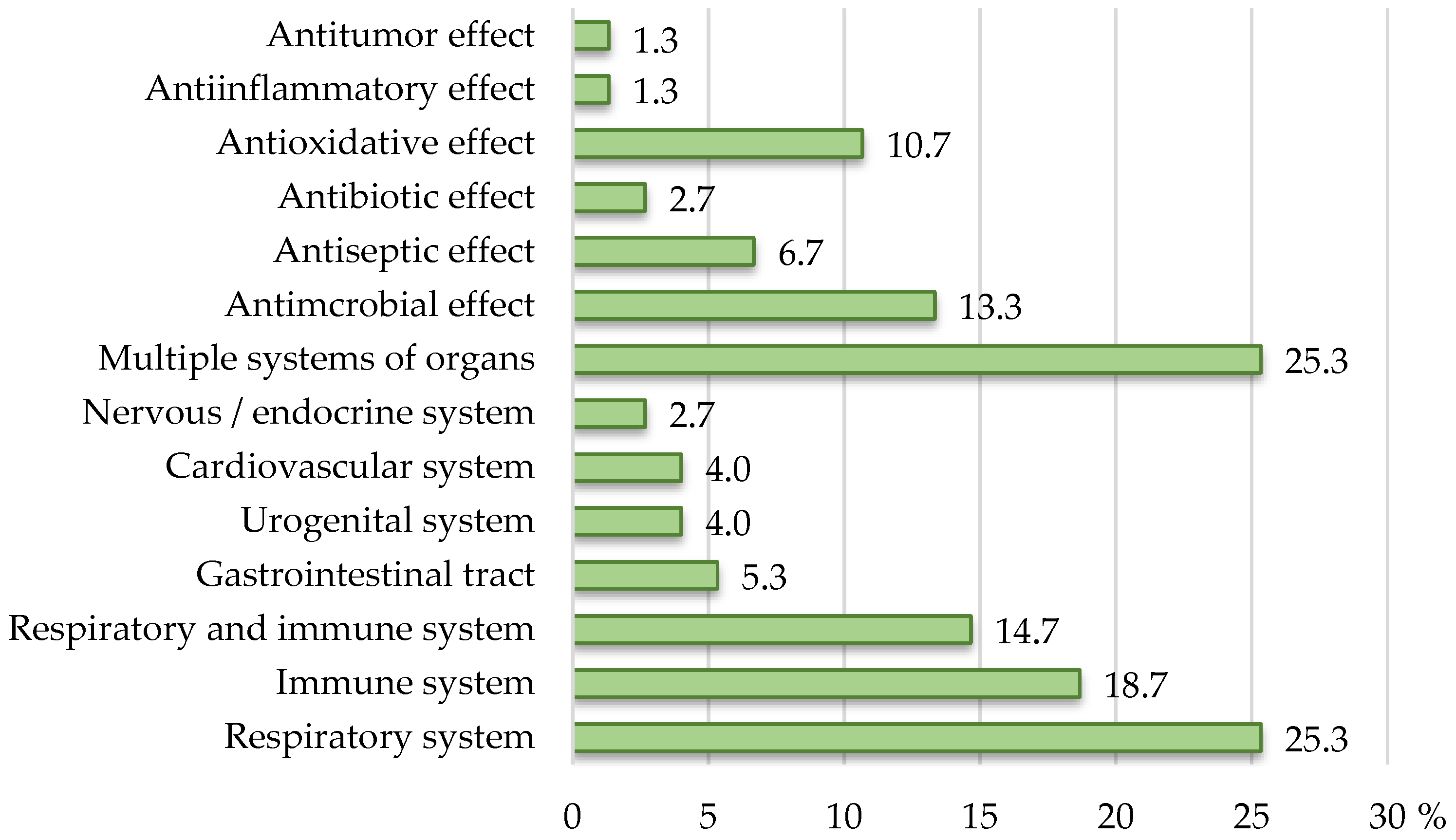

3.1. Regulatory Compliance of Health Claims

3.2. Attribution of Disease Prevention, Treatment, or Cure Properties

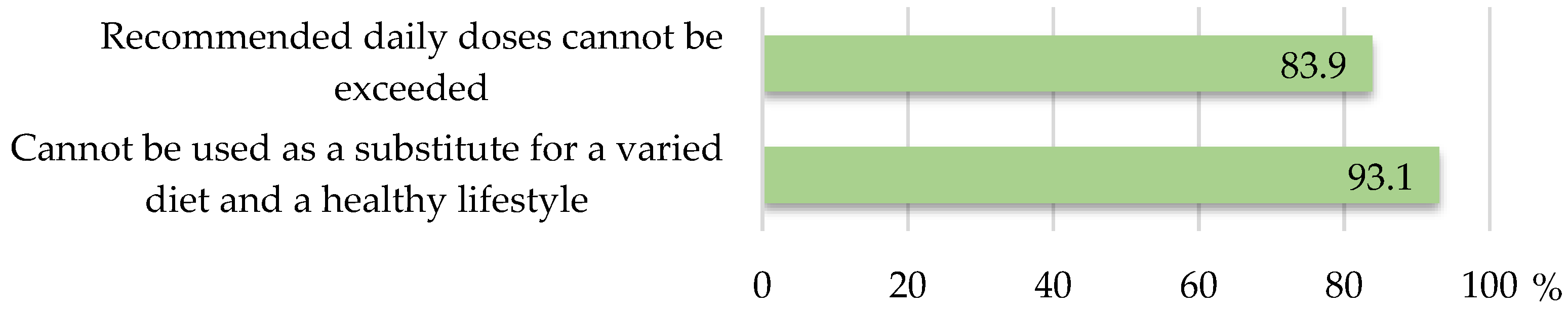

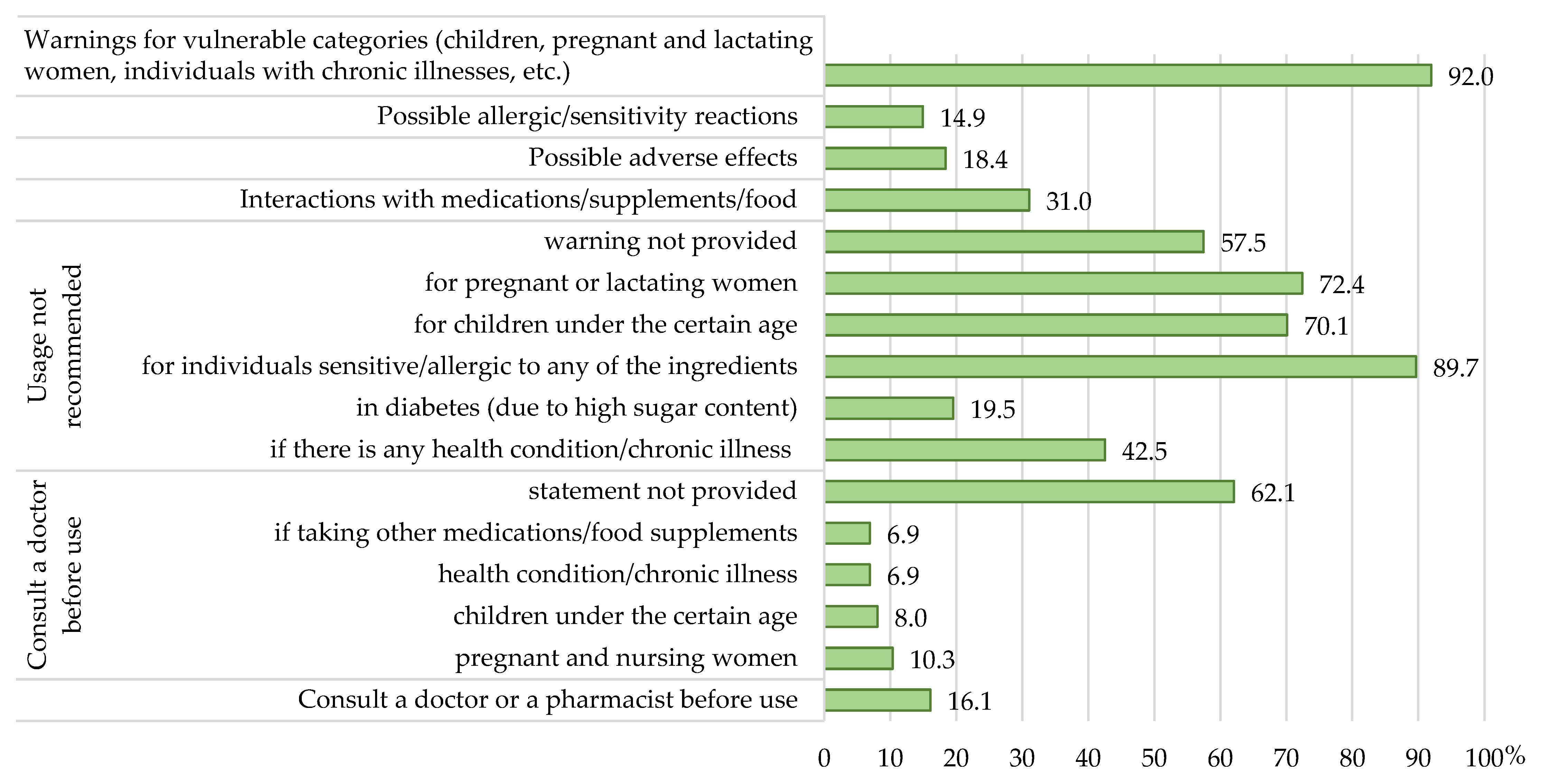

3.3. Regulatory Compliance of Precautionary and Warning Statements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tello, M.; Healthy Lifestyle: 5 Keys to a Longer Life. Harvard Medical School, Harvard Health Publishing. 2020. Available online: https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/healthy-lifestyle-5-keys-to-a-longer-life-2018070514186 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- de Boer, A. Fifteen years of regulating nutrition and health claims in Europe: The past, the present and the future. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grand View Research. Dietary Supplements Market Size, Share & Trend Analysis Report by Ingredient, by Form (Tablets, Capsules, Soft Gels, Powders, Gummies, Liquids, Others), by End-User, by Application, by Type, by Distribution Channel, by Region, and Segment Forecasts, 2024–2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/dietary-supplements-market (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- European Public Affairs. Consumer Survey on Food Supplements in the EU. Available online: https://foodsupplementseurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/FSE-Consumer_Survey-Ipsos-2022.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Starr, R.R. Too little, too late: Ineffective regulation of dietary supplements in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, B.; Hodgkins, C.; Shepherd, R.; Timotijevic, L.; Raats, M. An overview of consumer attitudes and beliefs about plant food supplements. Food Funct. 2011, 2, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djaoudene, O.; Romano, A.; Bradai, Y.D.; Zebiri, F.; Ouchene, A.; Yousfi, Y.; Amrane-Abider, M.; Sahraoui-Remini, Y.; Madani, K. A global overview of dietary supplements: Regulation, market trends, usage during the COVID-19 pandemic, and health effects. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamulka, J.; Jeruszka-Bielak, M.; Górnicka, M.; Drywień, M.E.; Zielinska-Pukos, M.A. Dietary supplements during COVID-19 outbreak. Results of Google trends analysis supported by PLifeCOVID-19 online studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kladar, N.; Bijelić, K.; Gatarić, B.; Bubić Pajić, N.; Hitl, M. Phytotherapy and Dietotherapy of COVID-19—An Online Survey Results from Central Part of Balkan Peninsula. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami, H.S.; Orabi, M.A.; Aldhabbah, F.M.; Alturki, H.N.; Aburas, W.I.; Alfayez, A.I.; Alharbi, A.S.; Almasuood, R.A.; Alsuhaibani, N.A. Knowledge about COVID-19 and beliefs about and use of herbal products during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2020, 28, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EC). Directive 2002/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 June 2002 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to food supplements. Off. J. Eur. Communities Legis. 2002, 45, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety. Off. J. Eur. Union 2002, 31, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar, S.; Anklam, E.; Xu, A.; Ulberth, F.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Hugas, M.; Sarma, N.; Crerar, S.; Swift, S.; et al. Regulatory landscape of dietary supplements and herbal medicines from a global perspective. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 114, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EC). Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2015 on novel foods. Off. J. Eur. Union 2015, 327, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, T. Consumers’ perceptions of the dietary supplement health and education act: Implications and recommendations. Drug Test Anal. 2016, 8, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banović Fuentes, J.; Amidžić, M.; Banović, J.; Torović, L. Internet marketing of dietary supplements for improving memory and cognitive abilities. PharmaNutrition 2024, 27, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EC). Regulation (EC) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers. Off. J. Eur. Union 2011, 304, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, 12, 18–63. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). EU Register of Health Claims. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/food-feed-portal/screen/health-claims/eu-register (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- European Parliament (EP). European Parliament Resolution of 18 January 2024 on the Implementation of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 on Nutrition and Health Claims Made on Foods (2023/2081(INI)). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2024-0040_EN.html (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- European Commission (EC). Regulation (EU) No 432/2012 of 16 May 2012 establishing a list of permitted health claims made on foods, other than those referring to the reduction of disease risk and to children’s development and health. Off. J. Eur. Union 2012, 136, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). Commission Staff Working Document Executive Summary of the Evaluation of the Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 on Nutrition and Health Claims Made on Foods with Regard to Nutrient Profiles and Health Claims Made on Plants and Their Preparations and of the General Regulatory Framework for Their Use in Foods {SWD(2020) 95 Final}. 2020. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/document/download/8a1fd953-fe9f-45b2-98eb-f9d242c44656_en?filename=labelling_nutrition-claims_swd_2020-96_sum_en.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Jovičić, J.; Novaković, B.; Grujičić, M.; Jusupović, F.; Mitrović, S. Health claims made on multivitamin and mineral supplements. J. Health Sci. 2011, 1, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banović Fuentes, J.; Beara, I.; Torović, L. Regulatory compliance of health claims on omega-3 fatty acid food supplements. Foods 2025, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensa, M.; Vovk, I.; Glavnik, V. Resveratrol food supplement products and the challenges of accurate label information to ensure food safety for consumers. Nutrients 2023, 15, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C.R.; Harris, C.M.; Miranda, M.I.; Kim, D.Y.; Hellberg, R.S. Labeling compliance and online claims for Ayurvedic herbal supplements on the US market associated with the purported treatment of COVID-19. Food Control 2023, 148, 109673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, S.V.; Granger, B.; Bauer, K.; Roberto, C.A. A content analysis of marketing on the packages of dietary supplements for weight loss and muscle building. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierzejska, R.E.; Wiosetek-Reske, A.; Siuba-Strzelińska, M.; Wojda, B. Health-related content of TV and radio advertising of dietary supplements—Analysis of legal aspects after introduction of self-regulation for advertising of these products in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muela-Molina, C.; Perelló-Oliver, S.; García-Arranz, A. False and misleading health-related claims in food supplements on Spanish radio: An analysis from a European Regulatory Framework. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 5156–5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avery, R.J.; Eisenberg, M.D.; Cantor, J.H. An examination of structure-function claims in dietary supplement advertising in the US: 2003–2009. Prev. Med. 2017, 97, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelica, A.; Aleksić, S.; Goločorbin-Kon, S.; Sazdanić, D.; Torović, L.; Cvejić, J. Internet marketing of cardioprotective dietary supplements. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2020, 26, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, C.; Baergen, R.; Puckett, D. Online sources of herbal product information. Am. J. Med. 2014, 127, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudischova, L.; Straznicka, J.; Pokladnikova, J.; Jahodar, L. The quality of information on the internet relating to top-selling dietary supplements in the Czech Republic. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2018, 40, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health of Republic of Serbia. Rulebook on food supplements (dietary supplements). Off. J. RS 2022, 45, 360–369, and 2023, 20, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Republic of Serbia. Rulebook on nutrition and health claims on the food’s labelling. Off. J. RS 2018, 51, 18–46, and 2018, 103, 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, A.; Scarborough, P.; Rayner, M. A systematic review, and meta-analyses, of the impact of health-related claims on dietary choices. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Mariani, A.; Vecchio, R. Consumer understanding and use of health claims: The case of functional foods. Recent Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 2014, 6, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nocella, G.; Kennedy, O. Food health claims—What consumers understand. Food Policy 2012, 37, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Autority (EFSA). Scientific Opinion on a Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) approach for the safety assessment of botanicals and botanical preparations. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3593. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Autority (EFSA). Botanical Summary Report. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/microstrategy/botanical-summary-report (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- European Food Safety Autority (EFSA). Guidance on Safety Assessment of Botanicals and Botanical Preparations Intended for Use as Ingredients in Food Supplements, on Request of EFSA. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Amidžić, M.; Banović Fuentes, J.; Banović, J.; Torović, L. Notifications and health consequences of unauthorized pharmaceuticals in food supplements. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojvodić, S.; Srđenović Čonić, B.; Torović, L. Safety assessment of herbal food supplements: Ethanol and residual solvents associated risk. J. Food Compost. Anal. 2023, 122, 105483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojvodić, S.; Srdjenović Čonić, B.; Torović, L. Benzoates and in situ formed benzene in food supplements and risk assessment. Food Addit. Contam. Part B 2023, 16, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torović, L.; Vojvodić, S.; Lukić, D.; Srđenović Čonić, B.; Bijelović, S. Safety assessment of herbal food supplements: Elemental profiling and associated risk. Foods 2023, 12, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N° | Regulation | Provision Type | Provision (Description) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Directive 2002/46/EC [11] | Requirements for label warnings and notes | The food supplements label shall contain a warning not to exceed the stated recommended daily dose, as well as a statement to the effect that food supplements should not be used as a substitute for a varied diet. |

| Prohibition | The labelling, presentation, and advertising must not attribute to food supplements the property of preventing, treating, or curing a human disease, or refer to such properties. | ||

| 2. | Regulation 1169/2011 [17] | Fair information practices | Food information shall not be misleading; food information shall be accurate, clear, and easy to understand for the consumer. |

| Prohibition | Food information shall not attribute to any food the property of preventing, treating or curing a human disease, nor refer to such properties. | ||

| Voluntary food information requirements | Food information provided voluntarily shall not mislead the consumer; shall not be ambiguous or confusing for the consumer; shall be based on the relevant scientific data. | ||

| 3. | Regulation 1924/2006 [18] | Definition of the claim | “Claim means any message or representation, …, including pictorial, graphic or symbolic representation, in any form, which states, suggests or implies that a food has particular characteristics”. |

| Definition of the health claim | “Health claim means any claim that states, suggests or implies that a relationship exists between a food category, a food or one of its constituents and health”. | ||

| Definition of the reduction in disease risk claim | “Reduction of disease risk claim means any health claim that states, suggests or implies that the consumption of a food category, a food or one of its constituents significantly reduces a risk factor in the development of a human disease”. | ||

| The use of nutrition and health claims | The use of nutrition and health claims shall not be false, ambiguous or misleading; give rise to doubt about the safety and/or the nutritional adequacy of other foods; encourage or condone excess consumption of a food; state, suggest or imply that a balanced and varied diet cannot provide appropriate quantities of nutrients in general. | ||

| Statement that should follow a health claim | Health claims shall be followed by a statement indicating the importance of a varied and balanced diet and a healthy lifestyle; the quantity of the food and pattern of consumption required to obtain the claimed beneficial effect; a statement addressed to persons who should avoid using the food; a warning for products that are likely to present a health risk if consumed in excess. | ||

| 4. | EU Register of Health Claims [19] | Inclusion in Register | The use of health claims shall only be permitted if they are authorized and included in the Register of authorized (permitted) health claims. |

| N | Composition | Compliance | Labelled Claims | “On-hold” Health Claims/Authorized Claims |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | β-Glucan elixir (natural bioactive polysaccharide of plant origin), zinc, vitamin C | fully compliant (health claims from the Register of authorized claims) | Contains a natural bioactive polysaccharide of plant origin, vitamin C, and zinc. | (Other (non-health) claims) |

| VITAMIN C contributes to the normal function of the immune system, protection of cells from oxidative stress, reduction of tiredness and fatigue. | Vitamin C contributes to the normal function of the immune system. Vitamin C contributes to the protection of cells from oxidative stress. Vitamin C contributes to the reduction of tiredness and fatigue. | |||

| ZINC contributes to the normal function of the immune system and plays a role in the process of cell division. | Zinc contributes to the normal function of the immune system. Zinc plays a role in the process of cell division. | |||

| 2 | Marshmallow, vitamin C | “on-hold“ claims compliant with EFSA Register of questions | For maintaining the health of the respiratory organs. | 3723—Althaea officinalis L. (Common name: Marshmallow)—Respiratory health: Soothing for mouth and throat/Relieves in case of tickle in the throat and pharynx/Soothing and pleasant effect on throat, pharynx, and vocal cords. |

| Marshmallow has a soothing and pleasant effect on the throat, pharynx, and vocal cords. | ||||

| It provides relief in case of throat, pharynx, and vocal cord irritation. | ||||

| 3 | Thyme, primrose, vitamin C | “on-hold“ claims compliant with EFSA Register of questions + health claims from the Register of authorized claims | Based on thyme, primrose, and vitamin C. | 4258—Primula veris (Common Name: Cowslip)—Health of the upper respiratory tract: Promotes upper respiratory tract health. |

| Primrose contributes to the relaxation and health of the upper respiratory tract and respiratory health. | 4259—Primula veris L. syn. Primula officinalis L. (Common name: Cowslip)—Respiratory health: Soothing for mouth and throat/Relieves in case of tickle in the throat and pharynx/Soothing and pleasant effect on throat, pharynx, and vocal cords | |||

| 4468—Primula officinalis (primrose)-radix—it sustains the respiratory apparatus; saponins have a secretolytic and secretomotor action: it favours expectoration of bronchial secretions. | ||||

| 3794—Primula veris L. em. heids—Contributes to relaxation and mental well-being: Helps to obtain a relaxation effect and regain a natural good temper. Contributes to the recovery of physical and mental well-being. | ||||

| Thyme contributes to respiratory health and maintains the normal function of the upper respiratory tract. | 2149—Thymus vulgaris/zygis (Common Name: Thyme)—Health of the upper respiratory tract: Soothing for throat and chest/contributes to wellbeing of chest and throat/contributes to a fresh breath ‘-Good for respiratory tract and/or throat, -Soothes respiratory tract | |||

| 2687—Common Thyme (Thymus vulgaris, Thymus zygis)—Supports secretion of mucus in the upper respiratory tract: Eases expectoration. Helps with a dry cough. | ||||

| 4167—Thymus vulgaris L. (Common name: Thyme)—Respiratory health: Soothing for mouth and throat/Relieves in case of irritation of throat and pharynx/Soothing and pleasant effect on throat, pharynx, and vocal cords | ||||

| Vitamin C contributes to the normal function of the immune system, reducing fatigue and tiredness, and protecting cells from oxidative stress. | Vitamin C contributes to the normal function of the immune system. Vitamin C contributes to the reduction of tiredness and fatigue. Vitamin C contributes to the protection of cells from oxidative stress. | |||

| 4 | Rosehip, primrose | partially NON-COMPLIANT (Register of authorized claims/“on-hold“ claims EFSA Register of questions) | TRADITIONALLY USED AS AN EXPECTORANT AND SUPPORT IN THE TREATMENT OF PRODUCTIVE COUGH. | 4258—Primula veris (common Name: Cowslip)—Health of the upper respiratory tract: Promotes upper respiratory tract health. |

| The active ingredients of primrose (saponins) locally irritate the mucous membrane of the respiratory organs, thereby increasing the secretion of bronchial mucus. | 4259—Primula veris L. syn. Primula officinalis L. (common name: Cowslip)—Respiratory health: Soothing for mouth and throat/Relieves in case of tickle in the throat and pharynx/Soothing and pleasant effect on throat, pharynx and vocal cords | |||

| Saponins reduce the surface tension of mucus, leading to a decrease in the density and viscosity of secretions, thus facilitating expectoration. | 4468—Primula officinalis (primrose)-radix- it sustains the respiratory apparatus; the saponins have a secretolytic and secretomotor action: it favours expectoration of bronchial secretions. | |||

| PRIMROSE, THROUGH β2 RECEPTORS LOCATED IN THE WALL OF THE RESPIRATORY ORGANS, DILATES THE BRONCHI AND FACILITATES BREATHING; | 3680—Rosa canina (common Name: Rose Hip)—Respiratory health: helps to soothe common cold/contributes to physical well-being/contributes to the body’s defence | |||

| EXHIBITS ANTIMICROBIAL AND ANTI-INFLAMMATORY EFFECTS. | ||||

| 5 | Lady’s mantle | fully NON-COMPLIANT (Register of authorized health claims/“on-hold“ claims EFSA Register of questions) | BENEFICIALLY ACTS AGAINST INFLAMMATION AND BACTERIA, IN POLYCYSTIC OVARIES, ON REGULATION OF THE SECRETION OF FEMALE HORMONES, BRINGING MENSTRUAL CYCLES IN ORDER. | 2203—Alchemilla vulgaris—Menstruation: Helps to maintain good comfort before and during the menstrual cycle |

| AGAINST DIARRHEA, RESPIRATORY TRACT INFLAMMATION, AND ANEMIA. | 2204—Alchemilla xanthochlora—common name: Lady’s Manthe—Vascular and Vein Health:/”Used for the good circulation of blood in microvessels”/”Helps to decrease the sensations of heavy legs”. | |||

| TO REDUCE RHEUMATIC PAIN, BLOOD SUGAR LEVEL, AND ELIMINATION OF WATER FROM THE BODY. | 2714—Alchemilla xanthochlora—common name: Lady’s Manthe—Vascular and Vein Health: “Traditionally used for the good circulation of blood in microvessels”/”Traditionally used to decrease the sensations of heavy legs”/”Used for the good circulation of blood in microvessels”/”Helps to decrease the sensations of heavy legs”. | |||

| 6 | Propolis | fully NON-COMPLIANT (claims for ingredients with no defined “on-hold” claims for specified purposes) | Propolis contains a wide spectrum of PHYSIOLOGICALLY ACTIVE SUBSTANCES such as bioflavonoids, phytohormones, essential oils, pollen, vitamins, micro- and macro-elements. | (No defined “on-hold” claims) |

| BACTERIOSTATIC, BACTERICIDAL, ANTIVIRAL, ANTIFUNGAL, IMMUNOSTIMULATORY, AND ANTITUMOR PROPERTIES. |

| Country | Type of Product (Composition or Intended Use) | Products Bearing Health Claims (N/N, %) | Description | Adherence (N/N, %) | Study/Data Year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Printed labels | ||||||

| Serbia | multivitamin and mineral | 22/48 (46%) | health claims in compliance with the list of approved claims | 7/22 (32%) | 2011/2010 | [23] |

| mandatory warning statements (claim about the importance of a varied and balanced diet and a healthy lifestyle) | 21/22 (95%) | |||||

| absence of expressions such as “prevention”, “treatment”, or “therapy”, attributing medicinal properties to products | 75% of claims | |||||

| Serbia | omega-3 fatty acid | 87/97 (89.7%) any health claim 68/97 (70.1%) claims referring to omega-3 fatty acids | health claims in compliance with the list of approved claims | 59/68 (86.8%) | 2025/2022–2023 | [24] |

| mandatory warning statements (claim about the importance of a varied and balanced diet and a healthy lifestyle) | 87/97 (89.7%) | |||||

| mandatory warning statement (keep out of reach of children) | 76/97 (78.4%) | |||||

| advice not to exceed the recommended daily dose | 78/97 (80.4%) | |||||

| warning that the supplement should not be used in children (specified for certain age groups) | 34/97 (35.1%) | |||||

| warning about the presence of allergens or sensitivity to certain ingredients/avoid use if an individual is allergic/sensitive to certain ingredients | 44/97 (45.4%) | |||||

| A warning requiring consultation with a doctor or pharmacist | 48/97 (49.5%) | |||||

| USA | Ayurvedic herbal | structure/function and general well-being claims: 35/51 (68.6%) physical product labels; 32/42 (76.2%) online listing | at least one U.S. regulatory noncompliance | 31/51 (60.8%) | 2023/2021 | [26] |

| missing/noncompliant disclaimers for structure/function or general well-being claims | 17/51 (33.3%) | |||||

| missing/noncompliant “Supplement Facts” label | 15/51 (29.4%) | |||||

| noncompliant statement of identity | 14/51 (27.5%) | |||||

| missing/noncompliant domestic mailing address or phone number | 13/51 (25.5%) | |||||

| disease claims | 4/51 (7.8%) of physical labels; 16/42 (38.1%) of online listings | |||||

| Slovenia | resveratrol | 8/20 (40%) | health claims compliant with the list of approved claims | 8/8 (100%) | 2023/2022 | [25] |

| the mandatory warning statements (claim emphasizing the importance of a varied and balanced diet and a healthy lifestyle) | 20/20 (100%) | |||||

| the warning for products that are likely to present a health risk if consumed in excess | 20/20 (100%) | |||||

| the warning for persons who should avoid the food | 13/20 (65%) | |||||

| USA | weight loss and muscle building | 6.5 (SD 2.5) claims per product | absence of a promising weight loss statement despite the lack of evidence to support such claims | 67/110 (60.9%) reduce body fat, BMI, promote weight loss; 35/110 (31.8%) guarantees success; 33/110 (30.0%) suppresses hunger, decreases appetite; 28/110 (25.5%) quick weight loss; 25/110 (22.7%) boosts metabolism | 2021/2013 | [27] |

| the presence of the FDA disclaimer | 59/110 (53.6%) | |||||

| the presence of warnings for vulnerable populations (children, pregnant or nursing women…) | 62/110 (56.4%) | |||||

| the presence of information on side effects | 67/110 (60.9%) | |||||

| absence of performance claims (fast acting, long-lasting…) | 30/110 (27.3%) | |||||

| Magazine, radio, and TV advertising | ||||||

| Poland (radio, TV) | dietary supplements | 46 products (76 health claims) | compliance with health/legal considerations within the framework of the EU regulation and the Polish regulation between TV broadcasting companies and supplement manufacturers | 46/46 (100%) | 2022/2020 | [28] |

| absence of unsubstantiated claims regarding effectiveness (promising weight loss or memory improvement) | 33/46 (71.8%) | |||||

| Spain (radio) | food supplements | 437 advertisements; 100% function claims; 89/437 (20.4%) prohibited disease claims; 38/437 (8.7%) reduction in disease risk claims | the presence of claims and supplement ingredients authorized by EFSA | 19.7% function claims; 79.6% disease claims; 0% reduction in disease risk claims | 2021/2017 | [29] |

| USA (magazines) | dietary supplements | 5350 structure–function claims/6179 advertisements (86.6%); 2.5 claims per ad | absence of verbs indicating a disease treatment/cure effect | (a significant number) | 2017/2003–2009 | [30] |

| absence of unsubstantiated validity claims that a product is “scientifically proven” or “guaranteed” | 79.5% | |||||

| Internet marketing | ||||||

| Google, Yahoo, Bing (Serbia) | cognitive improvement/degeneration prevention | 75/75 (100%) | the presence of the FDA disclaimer | 45/49 (91.8%) USA products | 2024/2023 | [16] |

| absence of unapproved claims | 1/11 (9.1%) EU products | |||||

| the presence of obligatory warnings | 31/75 (58.7%) | |||||

| the period of use specified | 8/75 (10.7%) | |||||

| the presence of precautions for overdose | 24/75 (32.0%) | |||||

| the precautions for vulnerable population(s) | 45/75 (60.0%) | |||||

| the presence of information on potential adverse effects | 58/75 (77.3%) | |||||

| Google, Yahoo, Bing (Serbia) | cardioprotective supplements (omega-3 fatty acids based) | 23/57 (40.4%) risk reduction claims 50/57 (87.7%) structure/function claims | the presence of claims authorized according to the FDA | 11/23 with claims (47.8%) | 2020/2018 | [31] |

| the presence of the FDA disclaimer | 34/57 (68.0%) | |||||

| the presence of information on the adverse effects | 1/57 (1.8%) | |||||

| the presence of information on possible interactions | 12/57 (21.0%) | |||||

| warnings regarding the use of the product | 38/57 (66.7%) | |||||

| Google (USA) | common herbal products | 13 products (top 50 websites of each product) | absence of claims related to the properties of treatment, prevention, or cure of a disease | 560/650 (86.2%) | 2014/2012–2013 | [32] |

| the presence of the FDA disclaimer | 54/650 (8.3%) | |||||

| recommendation to consult a healthcare professional before usage | 68/650 (10.5%) | |||||

| the presence of the information on safety (adverse effects, interaction, etc.) | <8% | |||||

| the presence of specific safety information related to the use by pregnant or lactating individuals | 46/650 (7.0%) | |||||

| Seznam, Google, Centrum (Czech R.) | top-selling food supplements | 100 supplements (199 web domains and 850 websites) | absence of claims related to the properties of treatment, prevention, or cure of a disease | 778/850 (91.5%) | 2018/2014 | [33] |

| absence of unauthorized health claims | 395/850 (46.5%) | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vojvodić, S.; Kobiljski, D.; Srđenović Čonić, B.; Torović, L. Landscape of Herbal Food Supplements: Where Do We Stand with Health Claims? Nutrients 2025, 17, 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091571

Vojvodić S, Kobiljski D, Srđenović Čonić B, Torović L. Landscape of Herbal Food Supplements: Where Do We Stand with Health Claims? Nutrients. 2025; 17(9):1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091571

Chicago/Turabian StyleVojvodić, Slađana, Dunja Kobiljski, Branislava Srđenović Čonić, and Ljilja Torović. 2025. "Landscape of Herbal Food Supplements: Where Do We Stand with Health Claims?" Nutrients 17, no. 9: 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091571

APA StyleVojvodić, S., Kobiljski, D., Srđenović Čonić, B., & Torović, L. (2025). Landscape of Herbal Food Supplements: Where Do We Stand with Health Claims? Nutrients, 17(9), 1571. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091571