A Survey of Allergic Consumers and Allergists on Precautionary Allergen Labelling: Where Do We Go from Here?

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Consumer Survey

3.2. Allergist Survey

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clarke, A.E.; Elliott, S.J.; St Pierre, Y.; Soller, L.; La Vieille, S.; Ben-Shoshan, M. Temporal trends in prevalence of food allergy in Canada. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 1428–1430.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaphylaxis and Allergy in the Emergency Department: Canada Institute for Health Information 2015. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/anaphylaxis-infosheet-en.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Primeau, M.N.; Kagan, R.; Joseph, L.; Lim, H.; Dufresne, C.; Duffy, C.; Prhcal, D.; Clarke, A. The psychological burden of peanut allergy as perceived by adults with peanut allergy and the parents of peanut-allergic children. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2000, 30, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, F.; Eigenmann, P.A. Clinical implications of food allergen thresholds. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2018, 48, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stensgaard, A.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Nielsen, D.; Munch, M.; DunnGalvin, A. Quality of life in childhood, adolescence and adult food allergy: Patient and parent perspectives. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2017, 47, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Canada. Allergens and Gluten Sources Labelling. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-allergies-intolerances/avoiding-allergens-food/allergen-labelling.html (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Health Canada. Food Allergen Labelling. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-labelling/allergen-labelling.html (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Dinardo, G.; Fierro, V.; del Giudice, M.M.; Urbani, S.; Fiocchi, A. Food-labeling issues for severe food-allergic consumers. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 23, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Vieille, S.; Hourihane, J.O.; Baumert, J.L. Precautionary Allergen Labeling: What Advice Is Available for Health Care Professionals, Allergists, and Allergic Consumers? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.; Eng, L.; Chang, C. Food Allergy Labeling Laws: International Guidelines for Residents and Travelers. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 65, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Canada. Food and Drugs Act, PART I Foods, Drugs, Cosmetics and Devices General. Section 5.1. 2012. Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/F-27.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- DunnGalvin, A.; Roberts, G.; Schnadt, S.; Astley, S.; Austin, M.; Blom, W.M.; Baumert, J.; Chan, C.; Crevel, R.W.; Grimshaw, K.E.; et al. Evidence-based approaches to the application of precautionary allergen labelling: Report from two iFAAM workshops. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2019, 49, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DunnGalvin, A.; Chan, C.; Crevel, R.; Grimshaw, K.; Poms, R.; Schnadt, S.; Taylor, S.L.; Turner, P.; Allen, K.J.; Austin, M.; et al. Precautionary allergen labelling: Perspectives from key stakeholder groups. Allergy 2015, 70, 1039–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinardo, G.; Dahdah, L.; Cafarotti, A.; Arasi, S.; Fierro, V.; Pecora, V.; Mazzuca, C.; Urbani, S.; Artesani, M.C.; Riccardi, C.; et al. Botanical Impurities in the Supply Chain: A New Allergenic Risk Exacerbated by Geopolitical Challenges. Nutrients 2024, 16, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Risk Assessment of Food Allergens-Part 2: Review and Establish Threshold Levels in Foods for the Priority Allergens. Meeting Report. Food Safety and Quality Series No. 15. Rome. 2022. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cc2946en (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- FAO; WHO. Risk Assessment of Food Allergens-Part 3: Review and Establish Precautionary Labelling in Foods of the Priority Allergens, Meeting Report. Food Safety and Quality Series No. 16. Rome. 2023. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cc6081en (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Allen, K.J.; Remington, B.C.; Baumert, J.L.; Crevel, R.W.; Houben, G.F.; Brooke-Taylor, S.; Kruizinga, A.G.; Taylor, S.L. Allergen reference doses for precautionary labeling (VITAL 2.0): Clinical implications. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remington, B.C.; Westerhout, J.; Meima, M.Y.; Blom, W.M.; Kruizinga, A.G.; Wheeler, M.W.; Taylor, S.L.; Houben, G.F.; Baumert, J.L. Updated population minimal eliciting dose distributions for use in risk assessment of 14 priority food allergens. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 139, 111259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.L.; Baumert, J.L.; Kruizinga, A.G.; Remington, B.C.; Crevel, R.W.; Brooke-Taylor, S.; Allen, K.J.; Houben, G. Establishment of Reference Doses for residues of allergenic foods: Report of the VITAL Expert Panel. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 63, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, N.; Adelman, D.C.; Anagnostou, K.; Baumert, J.L.; Blom, W.M.; Campbell, D.E.; Chinthrajah, R.S.; Mills, E.C.; Javed, B.; Purington, N.; et al. Using data from food challenges to inform management of consumers with food allergy: A systematic review with individual participant data meta-analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 2249–2262.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, P.J.; Patel, N.; Ballmer-Weber, B.K.; Baumert, J.L.; Blom, W.M.; Brooke-Taylor, S.; Brough, H.; Campbell, D.E.; Chen, H.; Chinthrajah, R.S.; et al. Peanut Can Be Used as a Reference Allergen for Hazard Characterization in Food Allergen Risk Management: A Rapid Evidence Assessment and Meta-Analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, C.B.; van den Dungen, M.W.; Cochrane, S.; Houben, G.F.; Knibb, R.C.; Knulst, A.C.; Ronsmans, S.; Yarham, R.A.; Schnadt, S.; Turner, P.J.; et al. Can we define a level of protection for allergic consumers that everyone can accept? Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 117, 104751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans-TCPS 2 (2022)-Chapter 2: Scope and Approach. Available online: https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/tcps2-eptc2_2022_chapter2-chapitre2.html (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Canadian Medical Association. Number of Physicians by Province/Territory and Specialty, Canada. 2019. Available online: https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/2019-11/2019-01-spec-prov_1.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Health Canada. Peanuts—A Priority Food Allergen. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/reports-publications/food-safety/peanuts-priority-food-allergen.html (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- Manny, E.; La Vieille, S.; Barrere, V.; Theolier, J.; Godefroy, S.B. Occurrence of milk and egg allergens in foodstuffs in Canada. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control. Expo. Risk Assess. 2021, 38, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, L.S.; Taylor, S.L.; Pacenza, R.; Niemann, L.M.; Lambrecht, D.M.; Sicherer, S.H. Food allergen advisory labeling and product contamination with egg, milk, and peanut. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126, 384–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, M.P.; Taylor, S.L. Risks associated with foods having advisory milk labeling. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125, 935–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, O.N.; Hourihane, J.O.; Remington, B.C.; Baumert, J.L.; Taylor, S.L. Survey of peanut levels in selected Irish food products bearing peanut allergen advisory labels. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control. Expo. Risk Assess. 2013, 30, 1467–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manny, E.; La Vieille, S.; Barrere, V.; Théolier, J.; Godefroy, S.B. Peanut and hazelnut occurrence as allergens in foodstuffs with precautionary allergen labeling in Canada. NPJ Sci. Food. 2021, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holleman, B.C.; van Os-Medendorp, H.; Bergh, H.v.D.; van Dijk, L.M.; Linders, Y.F.; Blom, W.M.; Verhoeckx, K.C.; Michelsen-Huisman, A.; Houben, G.F.; Knulst, A.C.; et al. Poor understanding of allergen labelling by allergic and non-allergic consumers. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2021, 51, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, K.J.; Turner, P.J.; Pawankar, R.; Taylor, S.; Sicherer, S.; Lack, G.; Rosario, N.; Ebisawa, M.; Wong, G.; Clare Mills, E.N.; et al. Precautionary labelling of foods for allergen content: Are we ready for a global framework? World Allergy Organ. J. 2014, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchisotto, M.J.; Harada, L.; Kamdar, O.; Smith, B.M.; Waserman, S.; Sicherer, S.; Allen, K.; Muraro, A.; Taylor, S.; Gupta, R.S. Food Allergen Labeling and Purchasing Habits in the United States and Canada. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2017, 5, 345–351.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicherer, S.H.; Abrams, E.M.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Hourihane, J.O. Managing Food Allergy When the Patient Is Not Highly Allergic. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Kanaley, M.; Negris, O.; Roach, A.; Bilaver, L. Understanding Precautionary Allergen Labeling (PAL) Preferences Among Food Allergy Stakeholders. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 254–264.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; WHO. Summary Report of the Ad Hoc Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Risk Assessment of Food Allergens. Part 1: Review and Validation of Codex Priority Allergen List Through Risk Assessment. 2021. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb4653en/cb4653en.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- FAO; WHO. Summary Report of the Ad Hoc Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Risk Assessment of Food Allergens. Part 2: Review and Establish Threshold Levels in Foods of the Priority Allergens—Virtual Follow-Up Meeting on Milk and Sesame. 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb9312en/cb9312en.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Baba, F.V.; Esfandiari, Z. Theoretical and practical aspects of risk communication in food safety: A review study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakwell, G.M. Risk communication: Factors affecting impact. Br. Med. Bull. 2000, 56, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DunnGalvin, A.; Roberts, G.; Regent, L.; Austin, M.; Kenna, F.; Schnadt, S.; Sanchez-Sanz, A.; Hernandez, P.; Hjorth, B.; Fernandez-Rivas, M.; et al. Understanding how consumers with food allergies make decisions based on precautionary labelling. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2019, 49, 1446–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, G.F.; Baumert, J.L.; Blom, W.M.; Kruizinga, A.G.; Meima, M.Y.; Remington, B.C.; Wheeler, M.W.; Westerhout, J.; Taylor, S.L. Full range of population Eliciting Dose values for 14 priority allergenic foods and recommendations for use in risk characterization. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 146, 111831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, F.; Caubet, J.C.; Eigenmann, P.A. Can my child with IgE-mediated peanut allergy introduce foods labeled with “may contain traces”? Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 31, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourihane, J.O.; Allen, K.J.; Shreffler, W.G.; Dunngalvin, G.; Nordlee, J.A.; Zurzolo, G.A.; Dunngalvin, A.; Gurrin, L.C.; Baumert, J.L.; Taylor, S.L. Peanut Allergen Threshold Study (PATS): Novel single-dose oral food challenge study to validate eliciting doses in children with peanut allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All Respondents | FAC Database | 3rd Party Panel | Two-Sided z-Test Results padj. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Sample Size | 1080 | 100% | 774 | 72% | 306 | 28% | n/a | |

| Adults with FA | 539 | 50% | 318 | 41% | 221 | 72% | <0.001 | |

| Parent of a child with FA—Age of child | 541 | 50% | 456 | 59% | 85 | 28% | <0.001 | |

| [0–5] | 130 | 24% | 106 | 23% | 24 | 28% | 0.399 | |

| [6–9] | 95 | 18% | 75 | 16% | 19 | 22% | 0.262 | |

| [10–12] | 79 | 15% | 64 | 14% | 15 | 18% | 0.464 | |

| [13–17] | 137 | 25% | 120 | 26% | 16 | 19% | 0.216 | |

| [18+] | 99 | 18% | 88 | 19% | 11 | 13% | 0.238 | |

| Single vs. Multiple FA | ||||||||

| Single | 334 | 31% | 202 | 26% | 131 | 43% | <0.001 | |

| Multiple | 746 | 69% | 571 | 74% | 175 | 57% | <0.001 | |

| Priority food allergens (in Canada) | ||||||||

| Peanuts | 581 | 54% | 489 | 63% | 91 | 30% | <0.001 | |

| Tree nuts | 545 | 50% | 477 | 62% | 68 | 22% | <0.001 | |

| Eggs | 211 | 20% | 173 | 22% | 38 | 12% | <0.001 | |

| Milk | 211 | 20% | 141 | 18% | 70 | 23% | 0.143 | |

| Shellfish-Crustaceans | 180 | 17% | 125 | 16% | 55 | 18% | 0.518 | |

| Shellfish-Molluscs | 161 | 15% | 106 | 14% | 54 | 18% | 0.167 | |

| Wheat and Triticale | 131 | 12% | 84 | 11% | 47 | 15% | 0.079 | |

| Sesame | 131 | 12% | 111 | 14% | 20 | 7% | 0.001 | |

| Fish | 119 | 11% | 81 | 10% | 37 | 12% | 0.500 | |

| Soy | 93 | 9% | 71 | 9% | 22 | 7% | 0.381 | |

| Mustard | 49 | 5% | 35 | 5% | 14 | 5% | 0.970 | |

| Sulphites | 68 | 6% | 45 | 6% | 23 | 8% | 0.381 | |

| Non-Priority food allergens (in Canada) | ||||||||

| Fruits | 115 | 11% | 87 | 11% | 29 | 9% | 0.466 | |

| Vegetables | 68 | 6% | 58 | 8% | 10 | 3% | 0.022 | |

| Who Diagnosed | ||||||||

| Allergist | 821 | 76% | 659 | 85% | 162 | 53% | <0.001 | |

| Family physician | 334 | 31% | 169 | 22% | 165 | 54% | <0.001 | |

| Emergency department physician | 207 | 19% | 171 | 22% | 36 | 12% | <0.001 | |

| Paediatrician | 95 | 9% | 70 | 9% | 24 | 8% | 0.569 | |

| Gastroenterologist | 56 | 5% | 40 | 5% | 17 | 6% | 0.817 | |

| Time since FA diagnosis | ||||||||

| Less than 6 months ago | 37 | 3% | 20 | 3% | 17 | 6% | 0.033 | |

| 6 to 11 months ago | 80 | 7% | 53 | 7% | 27 | 9% | 0.356 | |

| 1 to 2 years ago | 131 | 12% | 77 | 10% | 55 | 18% | <0.001 | |

| 3 to 5 years ago | 142 | 13% | 94 | 12% | 48 | 16% | 0.195 | |

| 6 to 10 years ago | 182 | 17% | 123 | 16% | 60 | 20% | 0.216 | |

| More than 10 years ago | 508 | 47% | 408 | 53% | 100 | 33% | <0.001 | |

| Epinephrine auto injector prescription | ||||||||

| Yes | 885 | 82% | 706 | 91% | 179 | 58% | <0.001 | |

| No | 194 | 18% | 67 | 9% | 127 | 42% | <0.001 | |

| Oral food challenge done | ||||||||

| Yes, in the past 3 years | 247 | 23% | 157 | 20% | 89 | 29% | 0.005 | |

| Yes, more than 3 years ago | 260 | 24% | 166 | 21% | 93 | 30% | 0.005 | |

| No | 573 | 53% | 450 | 58% | 123 | 40% | <0.001 | |

| Label | N | % | Explanatory Variable(s) | Categories | N | % | Logistic Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||||||

| OR [95%CI] | padj. | OR [95%CI] | padj. | |||||||

| Always reading ingredient labels | 627 | 58% | Sample | 3rd Party Panel | 98 | 32% | Ref. | |||

| FAC Database | 526 | 68% | 4.59 [3.45–6.10] | <0.001 | 2.93 [1.98–4.34] | <0.001 | ||||

| Age | >54 | 81 | 46% | Ref. | ||||||

| <18 | 286 | 65% | 2.17 [1.52–3.10] | <0.001 | 2.39 [1.44–3.99] | 0.004 | ||||

| [18–34] | 132 | 54% | 1.38 [0.93–2.03] | 0.140 | 1.80 [1.06–3.07] | 0.066 * | ||||

| [35–54] | 125 | 59% | 1.70 [1.14–2.55] | 0.015 | 2.91 [1.70–4.97] | <0.001 | ||||

| Gender | Male | 101 | 47% | Ref. | ||||||

| Female | 505 | 61% | 1.78 [1.32–2.41] | <0.001 | 0.95 [0.64–1.42] | 0.831 | ||||

| Income | <USD 100 K | 176 | 46% | Ref. | ||||||

| USD 100 K+ | 271 | 64% | 2.10 [1.58–2.79] | <0.001 | 1.28 [0.91–1.79] | 0.229 | ||||

| Epinephrine Prescribed | No | 66 | 34% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 558 | 63% | 3.32 [2.40–4.61] | <0.001 | 1.69 [1.08–2.64] | 0.052 * | ||||

| Food Allergy Type | Single | 170 | 51% | Ref. | ||||||

| Multiple | 455 | 61% | 1.54 [1.19–2.00] | 0.002 | 1.26 [0.89–1.78] | 0.253 | ||||

| Diagnosed by Allergist | No | 103 | 40% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 526 | 64% | 2.62 [1.97–3.50] | <0.001 | 1.57 [1.06–2.31] | 0.055 * | ||||

| Very confident of accuracy of ingredient information | 203 | 19% | Sample | 3rd Party Panel | 86 | 28% | Ref. | |||

| FAC Database | 116 | 15% | 0.46 [0.33–0.63] | <0.001 | 0.51 [0.33–0.80] | 0.013 | ||||

| Age | >54 | 28 | 16% | Ref. | ||||||

| <18 | 66 | 15% | 0.93 [0.58–1.52] | 0.853 | 0.99 [0.54–1.84] | 0.986 | ||||

| [18–34] | 56 | 23% | 1.61 [0.97–2.67] | 0.092 | 1.67 [0.91–3.04] | 0.180 | ||||

| [35–54] | 53 | 25% | 1.84 [1.10–3.06] | 0.029 | 1.59 [0.88–2.88] | 0.207 | ||||

| Gender | Male | 49 | 23% | Ref. | ||||||

| Female | 149 | 18% | 0.76 [0.53–1.10] | 0.185 | 1.09 [0.70–1.70] | 0.739 | ||||

| Income | <USD 100 K | 81 | 21% | Ref. | ||||||

| USD 100 K+ | 85 | 20% | 0.95 [0.67–1.35] | 0.853 | 1.30 [0.88–1.93] | 0.253 | ||||

| Epinephrine Prescribed | No | 49 | 25% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 150 | 17% | 0.63 [0.44–0.91] | 0.023 | 0.74 [0.46–1.19] | 0.274 | ||||

| Food Allergy Type | Single | 63 | 19% | Ref. | ||||||

| Multiple | 142 | 19% | 0.99 [0.71–1.38] | 0.972 | 1.30 [0.87–1.95] | 0.268 | ||||

| Diagnosed by Allergist | No | 57 | 22% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 148 | 18% | 0.74 [0.52–1.04] | 0.116 | 0.81 [0.53–1.25] | 0.387 | ||||

| Always/most of the time contacting a manufacturer | 181 | 17% | Sample | 3rd Party Panel | 86 | 28% | Ref. | |||

| FAC Database | 93 | 12% | 0.35 [0.25–0.49] | <0.001 | 0.25 [0.15–0.42] | <0.001 | ||||

| Age | >54 | 12 | 7% | Ref. | ||||||

| <18 | 84 | 19% | 2.84 [1.54–5.24] | 0.002 | 3.04 [1.33–6.95] | 0.026 | ||||

| [18–34] | 44 | 18% | 2.73 [1.43–5.22] | 0.004 | 2.38 [1.03–5.48] | 0.086 * | ||||

| [35–54] | 40 | 19% | 2.97 [1.54–5.74] | 0.002 | 3.05 [1.34–6.93] | 0.026 | ||||

| Gender | Male | 58 | 27% | Ref. | ||||||

| Female | 116 | 14% | 0.43 [0.30–0.62] | <0.001 | 0.56 [0.35–0.90] | 0.043 | ||||

| Income | <USD 100 K | 69 | 18% | Ref. | ||||||

| USD 100 K+ | 76 | 18% | 1.01 [0.70–1.46] | 0.972 | 1.25 [0.80–1.94] | 0.387 | ||||

| Epinephrine Prescribed | No | 29 | 15% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 150 | 17% | 1.22 [0.79–1.88] | 0.450 | 1.32 [0.75–2.35] | 0.387 | ||||

| Food Allergy Type | Single | 50 | 15% | Ref. | ||||||

| Multiple | 127 | 17% | 1.15 [0.81–1.63] | 0.517 | 1.44 [0.91–2.28] | 0.207 | ||||

| Diagnosed by Allergist | No | 41 | 16% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 140 | 17% | 1.05 [0.72–1.53] | 0.853 | 1.45 [0.87–2.43] | 0.229 | ||||

| All Respondents | FAC Database | 3rd Party Panel | Two-Sided z-Test Results padj. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Sample Size | 1080 | 100% | 774 | 72 | 306 | 28 | n/a |

| A low level of allergen is in the product | 124 | 11 | 59 | 8 | 65 | 21 | <0.001 |

| A low level of allergen may or may not be in the product | 530 | 49 | 404 | 52 | 126 | 41 | 0.003 |

| The allergen is not likely in the product and precautionary allergen labelling is used by the manufacturer for legal protection | 311 | 29 | 229 | 30 | 82 | 27 | 0.452 |

| The allergen is not in the product and precautionary allergen labelling is used by the manufacturer for legal protection | 55 | 5 | 36 | 5 | 19 | 6 | 0.452 |

| Don’t know/not sure | 59 | 5 | 44 | 6 | 15 | 5 | 0.610 |

| Label | N | % | Explanatory Variable(s) | Categories | N | % | Logistic Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||||||

| OR [95%CI] | padj. | OR [95%CI] | padj. | |||||||

| Aware that PAL is voluntary | 474 | 44% | Sample | 3rd Party Panel | 119 | 39% | Ref. | |||

| FAC Database | 356 | 46% | 1.32 [1.01–1.73] | 0.083 | 1.20 [0.82–1.76] | 0.458 | ||||

| Age | >54 | 53 | 30% | Ref. | ||||||

| <18 | 225 | 51% | 2.35 [1.62–3.42] | <0.001 | 2.52 [1.52–4.17] | 0.003 | ||||

| [18–34] | 103 | 42% | 1.70 [1.13–2.56] | 0.025 | 1.79 [1.06–3.03] | 0.089 * | ||||

| [35–54] | 91 | 43% | 1.71 [1.12–2.60] | 0.028 | 2.62 [1.55–4.41] | 0.003 | ||||

| Gender | Male | 103 | 48% | Ref. | ||||||

| Female | 356 | 43% | 0.83 [0.61–1.12] | 0.306 | 0.71 [0.49–1.04] | 0.163 | ||||

| Income | <USD 100 K | 157 | 41% | Ref. | ||||||

| USD 100 K+ | 199 | 47% | 1.28 [0.97–1.70] | 0.133 | 1.01 [0.74–1.39] | 0.950 | ||||

| Epinephrine Prescribed | No | 62 | 32% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 416 | 47% | 1.87 [1.35–2.60] | <0.001 | 1.49 [0.97–2.30] | 0.157 | ||||

| Food Allergy Type | Single | 140 | 42% | Ref. | ||||||

| Multiple | 336 | 45% | 1.10 [0.84–1.42] | 0.565 | 1.06 [0.77–1.47] | 0.818 | ||||

| Diagnosed by Allergist | No | 98 | 38% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 378 | 46% | 1.41 [1.06–1.87] | 0.041 | 1.04 [0.71–1.51] | 0.904 | ||||

| PAL considered as very useful | 573 | 53% | Sample | 3rd Party Panel | 153 | 50% | Ref. | |||

| FAC Database | 418 | 54% | 1.17 [0.89–1.52] | 0.347 | 0.98 [0.67–1.43] | 0.950 | ||||

| Age | >54 | 74 | 42% | Ref. | ||||||

| <18 | 260 | 59% | 2.03 [1.43–2.90] | <0.001 | 1.95 [1.21–3.12] | 0.029 | ||||

| [18–34] | 135 | 55% | 1.70 [1.15–2.52] | 0.018 | 1.46 [0.90–2.37] | 0.226 | ||||

| [35–54] | 100 | 47% | 1.23 [0.82–1.84] | 0.385 | 1.06 [0.66–1.72] | 0.894 | ||||

| Gender | Male | 107 | 50% | Ref. | ||||||

| Female | 447 | 54% | 1.18 [0.87–1.59] | 0.369 | 1.13 [0.78–1.63] | 0.644 | ||||

| Income | <USD 100 K | 196 | 51% | Ref. | ||||||

| USD 100 K+ | 233 | 55% | 1.16 [0.88–1.54] | 0.369 | 0.95 [0.70–1.30] | 0.865 | ||||

| Epinephrine Prescribed | No | 89 | 46% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 487 | 55% | 1.41 [1.03–1.93] | 0.061 | 1.31 [0.87–1.99] | 0.275 | ||||

| Food Allergy Type | Single | 180 | 54% | Ref. | ||||||

| Multiple | 388 | 52% | 0.92 [0.71–1.19] | 0.608 | 1.03 [0.75–1.42] | 0.904 | ||||

| Diagnosed by Allergist | No | 129 | 50% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 444 | 54% | 1.16 [0.88–1.54] | 0.369 | 0.85 [0.59–1.22] | 0.475 | ||||

| Products without PAL considered as unsafe | 482 | 45% | Sample | 3rd Party Panel | 122 | 40% | Ref. | |||

| FAC Database | 356 | 46% | 1.29 [0.99–1.69] | 0.105 | 1.58 [1.07–2.32] | 0.084 * | ||||

| Age | >54 | 76 | 43% | Ref. | ||||||

| <18 | 211 | 48% | 1.26 [0.89–1.80] | 0.280 | 1.74 [1.07–2.81] | 0.089 * | ||||

| [18–34] | 98 | 40% | 0.89 [0.60–1.31] | 0.618 | 1.40 [0.85–2.31] | 0.274 | ||||

| [35–54] | 95 | 45% | 1.09 [0.73–1.64] | 0.714 | 1.71 [1.04–2.81] | 0.092 * | ||||

| Gender | Male | 75 | 35% | Ref. | ||||||

| Female | 397 | 48% | 1.71 [1.25–2.34] | 0.002 | 1.44 [0.99–2.09] | 0.141 | ||||

| Income | <USD 100 K | 184 | 48% | Ref. | ||||||

| USD 100 K+ | 174 | 41% | 0.75 [0.56–0.99] | 0.083 | 0.62 [0.45–0.86] | 0.024 | ||||

| Epinephrine Prescribed | No | 87 | 45% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 390 | 44% | 0.96 [0.70–1.31] | 0.847 | 0.72 [0.47–1.10] | 0.226 | ||||

| Food Allergy Type | Single | 160 | 48% | Ref. | ||||||

| Multiple | 321 | 43% | 0.83 [0.64–1.08] | 0.240 | 0.78 [0.56–1.08] | 0.226 | ||||

| Diagnosed by Allergist | No | 114 | 44% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 370 | 45% | 1.04 [0.78–1.37] | 0.847 | 1.11 [0.76–1.60] | 0.722 | ||||

| Products with blanket statement considered as unsafe | 719 | 67% | Sample | 3rd Party Panel | 141 | 46% | Ref. | |||

| FAC Database | 580 | 75% | 3.74 [2.82–4.95] | <0.001 | 2.97 [2.00–4.41] | <0.001 | ||||

| Age | >54 | 109 | 62% | Ref. | ||||||

| <18 | 330 | 75% | 1.81 [1.24–2.65] | 0.006 | 2.01 [1.20–3.39] | 0.039 | ||||

| [18–34] | 159 | 65% | 1.12 [0.74–1.68] | 0.658 | 1.15 [0.68–1.93] | 0.722 | ||||

| [35–54] | 116 | 55% | 0.69 [0.46–1.05] | 0.133 | 0.98 [0.59–1.64] | 0.950 | ||||

| Gender | Male | 114 | 53% | Ref. | ||||||

| Female | 579 | 70% | 2.09 [1.53–2.85] | <0.001 | 1.38 [0.93–2.03] | 0.215 | ||||

| Income | <USD 100 K | 238 | 62% | Ref. | ||||||

| USD 100 K+ | 284 | 67% | 1.28 [0.95–1.72] | 0.159 | 0.77 [0.54–1.10] | 0.246 | ||||

| Epinephrine Prescribed | No | 95 | 49% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 620 | 70% | 2.49 [1.81–3.43] | <0.001 | 1.41 [0.91–2.19] | 0.226 | ||||

| Food Allergy Type | Single | 207 | 62% | Ref. | ||||||

| Multiple | 515 | 69% | 1.32 [1.01–1.74] | 0.083 | 1.24 [0.87–1.76] | 0.321 | ||||

| Diagnosed by Allergist | No | 155 | 60% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 567 | 69% | 1.49 [1.11–1.99] | 0.018 | 0.76 [0.51–1.13] | 0.263 | ||||

| Buying products with PAL at least some of the time | 580 | 54% | Sample | 3rd Party Panel | 245 | 80% | Ref. | |||

| FAC Database | 333 | 43% | 0.19 [0.14–0.27] | <0.001 | 0.28 [0.18–0.42] | <0.001 | ||||

| Age | >54 | 95 | 54% | Ref. | ||||||

| <18 | 203 | 46% | 0.72 [0.51–1.02] | 0.110 | 1.40 [0.85–2.32] | 0.274 | ||||

| [18–34] | 127 | 52% | 0.91 [0.62–1.35] | 0.696 | 1.46 [0.86–2.48] | 0.257 | ||||

| [35–54] | 152 | 72% | 2.21 [1.45–3.37] | <0.001 | 2.20 [1.28–3.78] | 0.024 | ||||

| Gender | Male | 146 | 68% | Ref. | ||||||

| Female | 414 | 50% | 0.46 [0.34–0.64] | <0.001 | 0.63 [0.42–0.95] | 0.089 | ||||

| Income | <USD 100 K | 253 | 66% | Ref. | ||||||

| USD 100 K+ | 208 | 49% | 0.50 [0.37–0.66] | <0.001 | 0.69 [0.49–0.96] | 0.089 | ||||

| Epinephrine Prescribed | No | 154 | 79% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 425 | 48% | 0.25 [0.17–0.36] | <0.001 | 0.43 [0.26–0.70] | 0.005 | ||||

| Food Allergy Type | Single | 184 | 55% | Ref. | ||||||

| Multiple | 395 | 53% | 0.90 [0.70–1.17] | 0.527 | 1.38 [0.98–1.95] | 0.157 | ||||

| Diagnosed by Allergist | No | 160 | 62% | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 419 | 51% | 0.65 [0.49–0.86] | 0.007 | 1.58 [1.04–2.39] | 0.089 * | ||||

| All Respondents | FAC Database | 3rd Party Panel | Two-Sided z-Test Results padj. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Sample Size | 1080 | 100% | 774 | 72 | 306 | 28 | n/a |

| Your perception of the likelihood of the allergen actually being in the product | 312 | 54 | 222 | 66 | 90 | 37 | <0.001 |

| No prior reactions to product (consumed product before without any reactions) | 304 | 52 | 217 | 65 | 87 | 36 | <0.001 |

| Type of allergen(s) | 279 | 48 | 173 | 51 | 106 | 43 | 0.071 |

| Information provided directly from manufacturer | 249 | 43 | 174 | 52 | 75 | 31 | <0.001 |

| Severity of reaction to that allergen(s) | 244 | 42 | 148 | 44 | 96 | 39 | 0.286 |

| Whether another similar product is available without a precautionary allergen label | 205 | 35 | 137 | 41 | 68 | 28 | 0.002 |

| Advice from allergist, doctor, or other health professional | 191 | 33 | 108 | 32 | 83 | 34 | 0.636 |

| Eating location (e.g., where the product will be eaten such as at home vs. outside the home) | 175 | 30 | 117 | 35 | 58 | 24 | 0.006 |

| The cost (e.g., the product with the precautionary allergen label is lower priced) | 72 | 12 | 25 | 7 | 47 | 19 | <0.001 |

| Province of Practice | |

| Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan | 8.77% (n = 5) |

| British Columbia | 8.77% (n = 5) |

| Nova Scotia | 8.77% (n = 5) |

| Ontario | 38.6% (n = 22) |

| Quebec | 35.1% (n = 20) |

| Years of experience | |

| <1 year to 5 years | 28.07% (n = 16) |

| 6–10 years | 19.3% (n = 11) |

| 11–20 years | 10.53% (n = 6) |

| 20 years or more | 42.1% (n = 24) |

| Type of patients seen | |

| Adults | 14.04% (n = 8) |

| Children | 35.09% (n = 20) |

| Both adults and children | 50.88% (n = 29) |

| Type of practice * | |

| Academic | 50.88% (n = 29) |

| Community Hospital Centre | 21.05% (n = 12) |

| Private Practice | 68.42% (n = 39) |

| Mixed Private practice and Academic | 35% (n = 27) |

| OFCs performed | |

| Daily | 33.3% (n = 19) |

| Weekly to Once a month | 52.6% (n = 30) |

| Rarely (i.e., a few times a year) or Never | 14.04% (n = 8) |

| Key Messages of Consumer Survey | Key Messages of Allergist Survey |

|---|---|

| More than half of consumers (53%) consider that PAL is a useful tool. However, they find it confusing in its current form. Seeing PAL statements on food products makes them feel that the manufacturer is more aware of allergens and is taking it seriously. | Half of surveyed allergists think PAL is not useful in its current form. |

| More than half of consumers (54%) will purchase products that have a PAL statement at least on occasion. | The majority of Canadian allergists surveyed allowed foods with PAL in a proportion of patients with IgE-mediated food allergies based on patient-specific factors and shared decision making (69% for adults and 83% for children). |

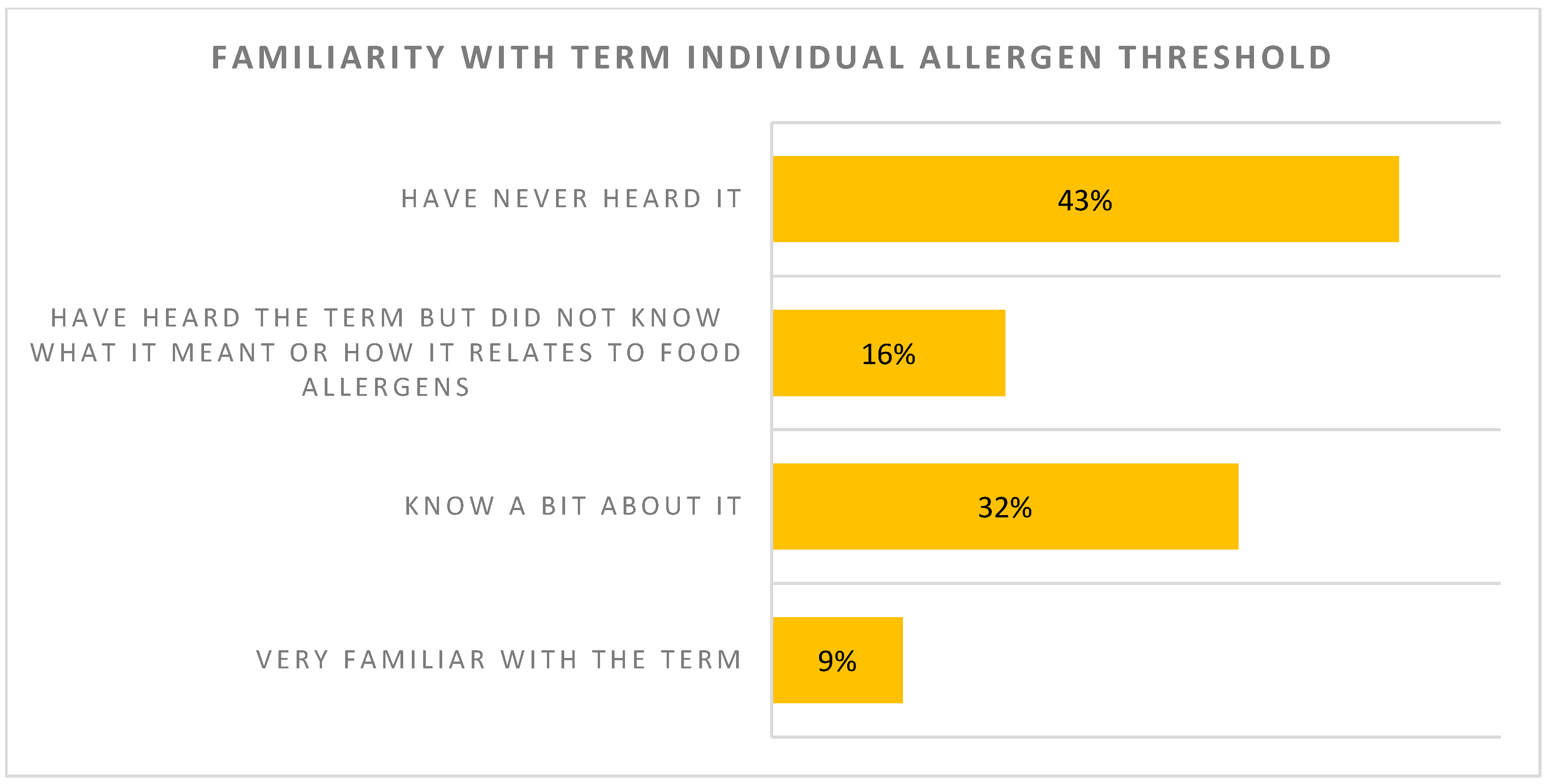

| The majority of surveyed individuals (59%) have not heard the term “individual allergen threshold” or have heard the term but did not know what it meant. | Reaction threshold on an oral food challenge is perceived as an important deciding factor when giving recommendations towards avoidance or introduction of foods with PAL. |

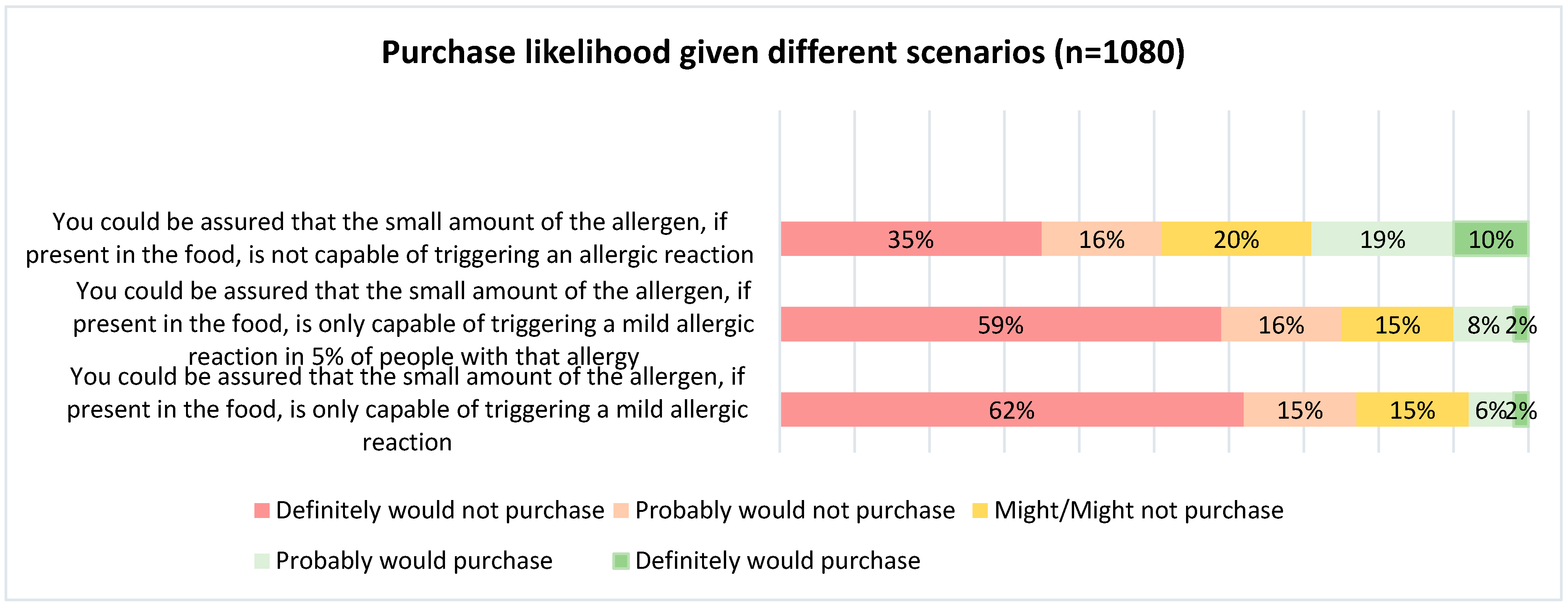

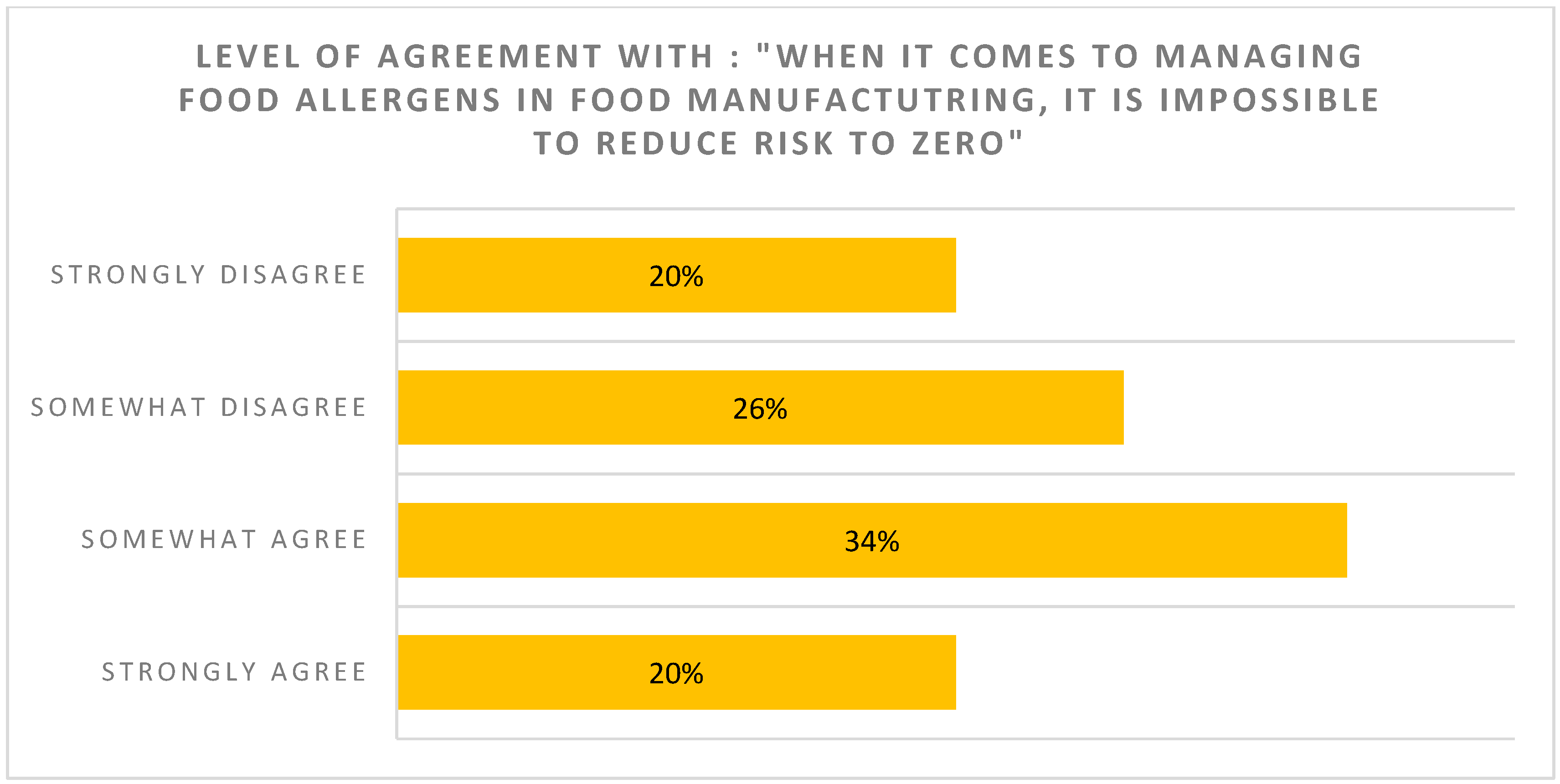

| Consumers are reluctant to buy foods with even a small amount of their allergen in the product, even if they could be assured that the small amount of allergen is not capable of triggering an allergic reaction | Most allergists think PAL should not be too restrictive (PAL should not be used if unlikely to trigger reaction in the majority of patients) |

| Surveyed allergists are open to perform single-dose oral food challenges to stratify low-risk patients who could benefit from PAL introduction, although obstacles are mentioned. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Graham, F.; Waserman, S.; Gerdts, J.; Povolo, B.; Bonvalot, Y.; La Vieille, S. A Survey of Allergic Consumers and Allergists on Precautionary Allergen Labelling: Where Do We Go from Here? Nutrients 2025, 17, 1556. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091556

Graham F, Waserman S, Gerdts J, Povolo B, Bonvalot Y, La Vieille S. A Survey of Allergic Consumers and Allergists on Precautionary Allergen Labelling: Where Do We Go from Here? Nutrients. 2025; 17(9):1556. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091556

Chicago/Turabian StyleGraham, François, Susan Waserman, Jennifer Gerdts, Beatrice Povolo, Yvette Bonvalot, and Sébastien La Vieille. 2025. "A Survey of Allergic Consumers and Allergists on Precautionary Allergen Labelling: Where Do We Go from Here?" Nutrients 17, no. 9: 1556. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091556

APA StyleGraham, F., Waserman, S., Gerdts, J., Povolo, B., Bonvalot, Y., & La Vieille, S. (2025). A Survey of Allergic Consumers and Allergists on Precautionary Allergen Labelling: Where Do We Go from Here? Nutrients, 17(9), 1556. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091556