Use of Oligomeric Formulas in Malabsorption: A Delphi Study and Consensus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

2.1. Phase 1

2.2. Phase 2

2.3. Phase 3

2.4. Phase 4

2.5. Scoring Method

2.6. Methods of Analysis

2.7. Data Analysis

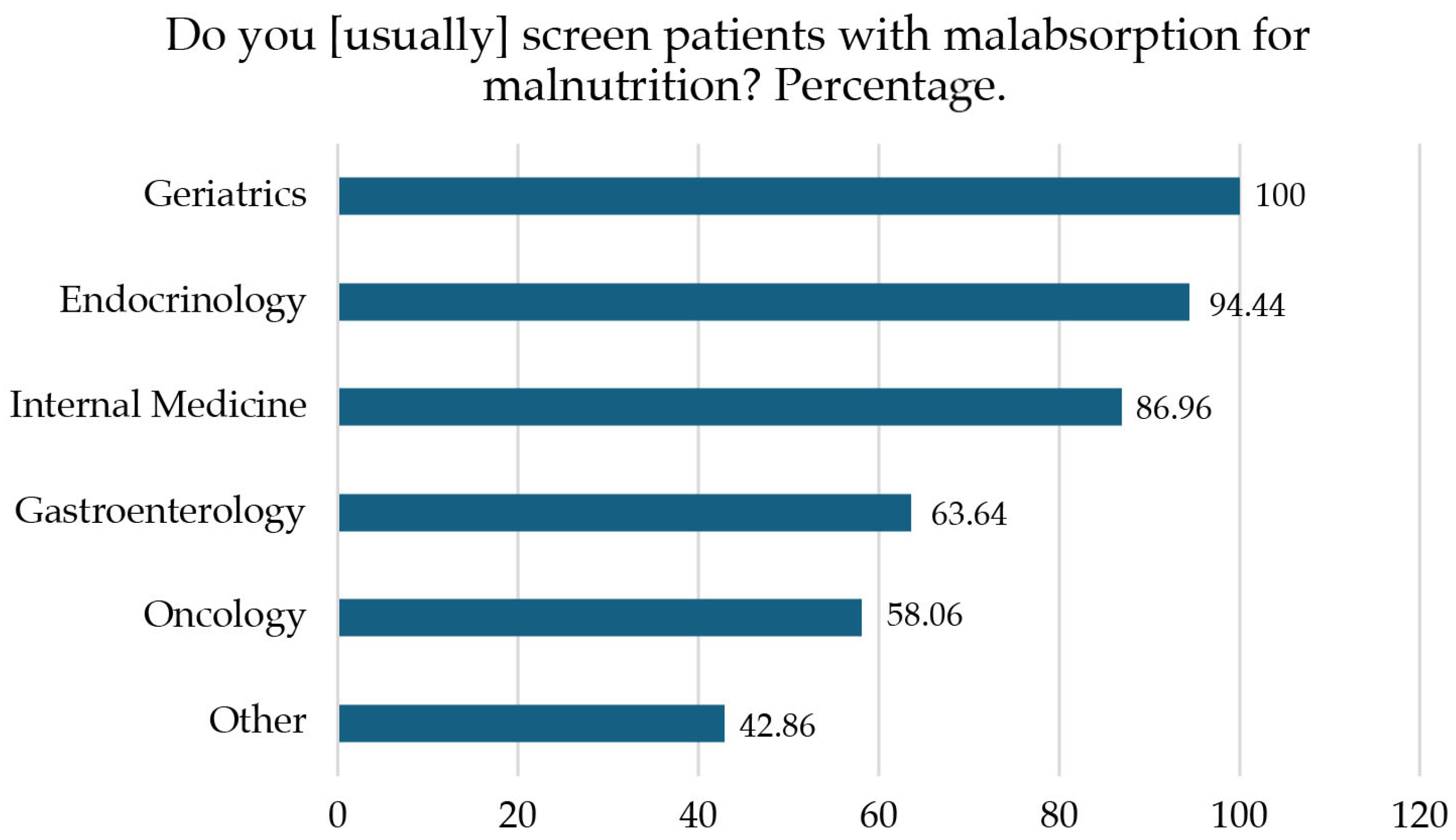

3. Results

3.1. Gastrointestinal Symptoms That Involve Malabsorption Syndrome and Compromise Nutritional Status

3.2. Oral Nutritional Supplementation (ONS) as Nutritional Therapy in Malabsorption Syndrome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schiller, L.R. Maldigestion Versus Malabsorption in the Elderly. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2020, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heide, F. Acquired causes of intestinal malabsorption. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 30, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, Z.; Osayande, A.S. Selected disorders of malabsorption. Prim. Care 2011, 38, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.; Johnson, R. Malabsorption Syndromes. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 53, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Micic, D. Nutrition Considerations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2021, 36, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocîrlan, M.; Ciocîrlan, M.; Iacob, R.; Tanțău, A.; Gheorghe, L.; Gheorghe, C.; Dobru, D.; Constantinescu, G.; Cijevschi, C.; Trifan, A.; et al. Malnutrition Prevalence in Newly Diagnosed Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—Data from the National Romanian Database. J. Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2019, 28, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareque, M.M.; Mcdonald, J.; Wakefield, S. OGC SO05—Prevalence of Malabsorption and Impact on Quality of Life After Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2024, 111 (Suppl. S9), znae271-130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneghan, H.M.; Zaborowski, A.; Fanning, M.; McHugh, A.; Doyle, S.; Moore, J.; Ravi, N.; Reynolds, J.V. Prospective Study of Malabsorption and Malnutrition After Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Surgery. Ann. Surg. 2015, 262, 803–807, discussion 807–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billeter, A.T.; Fischer, L.; Wekerle, A.L.; Senft, J.; Müller-Stich, B. Malabsorption as a Therapeutic Approach in Bariatric Surgery. Viszeralmedizin 2014, 30, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Barazzoni, R.; Austin, P.; Ballmer, P.; Biolo, G.; Bischoff, S.C.; Compher, C.; Correia, I.; Higashiguchi, T.; Holst, M.; et al. ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seres, D.S.; Ippolito, P.R. Pilot study evaluating the efficacy, tolerance and safety of a peptide-based enteral formula versus a high protein enteral formula in multiple ICU settings (medical, surgical, cardiothoracic). Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 706–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Elfadil, O.; Steien, D.B.; Narasimhan, R.; Velapati, S.R.; Epp, L.; Patel, I.; Patel, J.; Hurt, R.T.; Mundi, M.S. Transition to peptide-based diet improved enteral nutrition tolerance and decreased healthcare utilization in pediatric home enteral nutrition. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2022, 46, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitakis, M.; Ockenga, J.; Bezmarevic, M.; Gianotti, L.; Krznarić, Ž.; Lobo, D.N.; Löser, C.; Madl, C.; Meier, R.; Phillips, M.; et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in acute and chronic pancreatitis. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 612–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Paris, A.; Martinez-García, M.; Martinez-Trufero, J.; Lambea-Sorrosal, J.; Calvo-Gracia, F.; López-Alaminos, M.E. Oligomeric Enteral Nutrition in Undernutrition, due to Oncology Treatment-Related Diarrhea. Systematic Review and Proposal of An Algorithm of Action. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, M.-Y.; Tang, H.-C.; Hu, S.-H.; Chang, S.-J. Peptide-based enteral formula improves tolerance and clinical outcomes in abdominal surgery patients relative to a whole protein enteral formula. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2016, 8, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Q.; Li, Y.-H.; Li, Y.-T.; Li, H.-X.; Zhang, D. Comparisons between short-peptide formula and intact-protein formula for early enteral nutrition initiation in patients with acute gastrointestinal injury: A single-center retrospective cohort study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Elfadil, O.; Shah, R.N.; Hurt, R.T.; Mundi, M.S. Peptide-based formula: Clinical applications and benefits. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2023, 38, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquerizo Alonso, C.; Bordejé Laguna, L.; Fernández-Ortega, J.F.; Bordejé Laguna, M.L.; Fernández Ortega, J.F.; García de Lorenzo y Mateos, A.; Carmona, T.G.; Meseguer, J.H.; Arizmendi, A.M.; González, J.M.; et al. Recomendaciones para el tratamiento nutrometabólico especializado del paciente crítico: Introducción, metodología y listado de recomendaciones. Grupo de Trabajo de Metabolismo y Nutrición de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva, Crítica y Unidades Coronarias (SEMICYUC). Med. Intensiv. 2020, 44, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- De Luis Román, D.; Domínguez Medina, E.; Molina Baena, B.; Matía-Martín, P. Oligomeric Formulas in Surgery: A Delphi and Consensus Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey-Murto, S.; Varpio, L.; Wood, T.J.; Gonsalves, C.; Ufholz, L.A.; Mascioli, K.; Wang, C.; Foth, T. The Use of the Delphi and Other Consensus Group Methods in Medical Education Research: A Review. Acad. Med. 2017, 92, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsegard, V.L.; Ferlay, O.; Maisonneuve, N.; Kyle, U.G.; Dupertuis, Y.M.; Genton, L.; Pichard, C. Outil de dépistage simplifié de la dénutrition: Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) [Simplified malnutrition screening tool: Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST)]. Rev. Med. Suisse Romande 2004, 124, 601–605. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein, L.Z.; Harker, J.O.; Salvà, A.; Guigoz, Y.; Vellas, B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: Developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M366–M372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Guaitoli, P.R.; Jansma, E.P.; de Vet, H.C.W. Nutrition screening tools: Does one size fit all? A systematic review of screening tools for the hospital setting. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalto, M.; Santoro, L.; D’Onofrio, F.; Curigliano, V.; Visca, D.; Gallo, A.; Cammarota, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Gasbarrini, G. Classification of malabsorption syndromes. Dig. Dis. 2008, 26, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, P.; Fehr, R.; Baechli, V.; Geiser, M.; Deiss, M.; Gomes, F.; Kutz, A.; Tribolet, P.; Bregenzer, T.; Braun, N.; et al. Individualised nutritional support in medical inpatients at nutritional risk: A randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 2312–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez, Á.; Zamar, E.; Risso, S.; Casiraghi, M.; Fiameni, A.; Evangelista, N. Tratado de Fibrosis Quística. Prensa Medica Argent. 2012, 89, 1–554. [Google Scholar]

- Sankararaman, S.; Schindler, T.; Sferra, T.J. Management of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency in Children. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2019, 34 (Suppl. S1), S27–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVallee, C.; Seelam, P.; Balakrishnan, S.; Lowen, C.; Henrikson, A.; Kesting, B.; Perugini, M.; Araujo Torres, K. Real-World Evidence of Treatment, Tolerance, Healthcare Utilization, and Costs Among Postacute Care Adult Patients Receiving Enteral Peptide-Based Diets in the United States. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2021, 45, 1729–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, A.; Escher, J.; Hébuterne, X.; Kłęk, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Schneider, S.; Shamir, R.; Stardelova, K.; Wierdsma, N.; Wiskin, A.E.; et al. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeyen, G.; Berrevoet, F.; Borbath, I.; Geboes, K.; Peeters, M.; Topal, B.; Van Cutsem, E.; Van Laethem, J.-L. Expert opinion on management of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency in pancreatic cancer. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesia, D.D.L.; Avci, B.; Kiriukova, M.; Panic, N.; Bozhychko, M.; Sandru, V.; de Madaria, E.; Capurso, G. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2020, 8, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curry, A.S.; Chadda, S.; Danel, A.; Nguyen, D.L. Early introduction of a semi-elemental formula may be cost saving compared to a polymeric formula among critically ill patients requiring enteral nutrition: A cohort cost-consequence model. Clin. Outcomes Res. 2018, 10, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 59 | (37.82) |

| Female | 97 | (62.18) | |

| Medical specialty | Endocrinology | 72 | (46.15) |

| Oncology | 31 | (19.87) | |

| Gastroenterology | 22 | (14.10) | |

| Internal Medicine | 23 | (14.74) | |

| Geriatrics | 1 | (0.64) | |

| Other | 7 | (4.49) | |

| Variable | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age | Years | 41.74 (8.52) | |

| Experience 1 | Years | 12.43 (8.4) | |

| Question Text | Round 1 | Round 2 | Consensus (Yes/No) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you think that patients with malabsorption should be screened for malnutrition? | Median 9 (IQR 0) | Yes | |

| Do you think a protocol should be available in your department for the nutritional management of your patients? | Median 9 (IQR 1) | Yes | |

| Do you think there should be some type of protocol for the treatment of malabsorption syndrome? | Median 9 (IQR 1) | Yes | |

| Do you think there should be a protocol for quantifying the symptoms associated with malabsorption? | Median 9 (IQR 1) | Yes | |

| In your opinion, which of the following symptoms make up malabsorption syndrome? | |||

| Vomiting | Median 5 (IQR 3) | 39.7% | No |

| Abdominal distension | Median 8 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Nausea | Median 6 (IQR 3) | 48.1% | No |

| Increased gastric residues | Median 6.5 (IQR 3) | 61.5% | Yes |

| Abdominal pain | Median 8 (IQR 3) | Yes | |

| Diarrhea | Median 9 (IQR 1) | Yes | |

| Reflux | Median 5 (IQR 3) | 27.6% | No |

| In your opinion, which of the following symptoms would most affect nutritional status? | |||

| Vomiting | Median 8 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Abdominal distention | Median 6 (IQR 2) | 71.2% | Yes |

| Nausea | Median 7 (IQR 3) | Yes | |

| Increased gastric residues | Median 7 (IQR 3) | Yes | |

| Abdominal pain | Median 8 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Diarrhea | Median 9 (IQR 1) | Yes | |

| Reflux | Median 6 (IQR 2) | 38.5% | No |

| Do you usually modify the type of nutritional supplementation based on the severity of the current gastrointestinal symptoms by prescribing oligomeric formulas if the symptoms are severe? | Median 8 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| In your clinical experience, patients with malabsorption syndrome have poorer tolerance to polymeric formulas. | Median 7 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| In your clinical experience, oligomeric formulas are effective as first choice in enteral support for patients with suspected malabsorption/maldigestion syndrome with: | |||

| Vomiting | Median 6 (IQR 3) | 45.5% | No |

| Abdominal distention | Median 7 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Nausea | Median 6 (IQR 3) | 42.3% | No |

| Increased gastric residues | Median 6 (IQR 3) | 54.4% | Yes |

| Abdominal pain | Median 7 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Diarrhea | Median 8 (IQR 1) | Yes | |

| Reflux | Median 5.5 (IQR 3) | 35.3% | No |

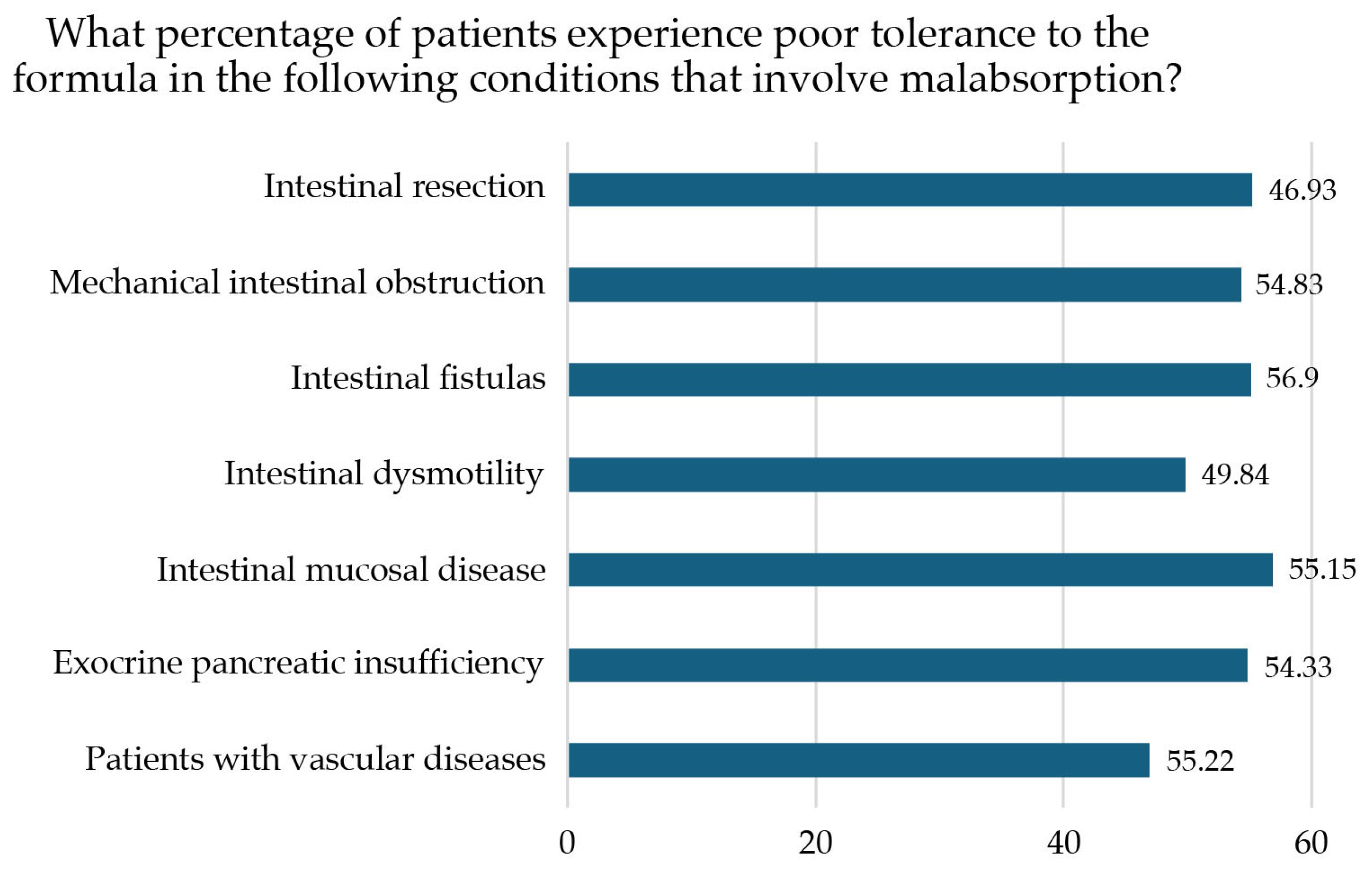

| Do you believe that poor tolerance of the polymeric formula frequently occurs in the following malabsorption conditions? | |||

| Intestinal resection (short bowel syndrome, bariatric surgery) | Median 7 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Mechanical intestinal obstruction (Crohn’s stenosis, extensive adhesions, or peritoneal carcinomas) | Median 7 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Intestinal fistulas (Crohn’s disease, diverticular disease, pancreatic disease, radiation enteritis, colon cancer, ovarian cancer, small bowel cancer) | Median 7 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Intestinal dysmotility (diabetes, ileus, systemic scleroderma, amyloidosis) | Median 7 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Mucosal intestinal disease (Crohn’s disease, Celiac disease, radiation enteritis, autoimmune enteropathy, ulcerative colitis, amyloidosis, giardiasis, Whipple disease) | Median 7 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (unresectable pancreatic cancer, chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, somatostatin analog therapy) | Median 7 (IQR 3) | Yes | |

| Patients with vascular diseases (mesenteric vascular failure, mesenteric ischemia) | Median 6 (IQR 2) | 53.2% | Yes |

| Do you think the presence and severity of any of the following symptoms are predictors of poor tolerance to polymeric nutritional supplementation? | |||

| Vomiting | Median 7 (IQR 3) | Yes | |

| Abdominal distention | Median 7 (IQR 1) | Yes | |

| Nausea | Median 6 (IQR 2,5) | 70.5% | Yes |

| Increased gastric residues | Median 7 (IQR 3) | Yes | |

| Abdominal pain | Median 7 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Diarrhea | Median 8 (IQR 1) | Yes | |

| Reflux | Median 6 (IQR 2) | 39.1% | No |

| The use of oligomeric formulas as first choice to subsequently switch to polymeric formulas is an efficient strategy (saving visits and resources) when malabsorption/maldigestion is suspected in case of: | |||

| Intestinal resection (short bowel syndrome, bariatric surgery) | Median 7.5 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Mechanical intestinal obstruction (Crohn’s stenosis, extensive adhesions, or peritoneal carcinomas) | Median 7 (IQR 3) | Yes | |

| Intestinal fistulas (Crohn’s disease, diverticular disease, pancreatic disease, radiation enteritis, colon cancer, ovarian cancer, small bowel cancer) | Median 7(IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Intestinal dysmotility (diabetes, ileus, systemic scleroderma, amyloidosis) | Median 7 (IQR 3) | Yes | |

| Mucosal intestinal disease (Crohn’s disease, Celiac disease, radiation enteritis, autoimmune enteropathy, ulcerative colitis, amyloidosis, giardiasis, Whipple disease) | Median 8 (IQR 1,5) | Yes | |

| Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (unresectable pancreatic cancer, chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, somatostatin analog therapy) | Median 7 (IQR 2) | Yes | |

| Patients with vascular diseases (mesenteric vascular failure, mesenteric ischemia) | Median 7 (IQR 3) | Yes | |

| Do you consider it a good strategy to start nutritional treatment with an oligomeric formula and then switch to a polymeric formula after the patient’s gastrointestinal symptoms are recovered? | Median 8 (IQR 2) | Yes |

| N | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intestinal resection (short bowel syndrome, bariatric surgery) | 117 | 14.42 | 34.7 |

| Mechanical intestinal obstruction (Crohn’s stenosis, extensive adhesions, or peritoneal carcinomas) | 117 | 13.99 | 36.3 |

| Intestinal fistulas (Crohn’s disease, diverticular disease, pancreatic disease, radiation enteritis, colon cancer, ovarian cancer, small bowel cancer) | 117 | 10.58 | 12.1 |

| Intestinal dysmotility (diabetes, ileus, systemic scleroderma, amyloidosis) | 117 | 12.03 | 35.1 |

| Mucosal intestinal disease (Crohn’s disease, Celiac disease, radiation enteritis, autoimmune enteropathy, ulcerative colitis, amyloidosis, giardiasis, Whipple disease) | 117 | 14.09 | 35.3 |

| Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (unresectable pancreatic cancer, chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, somatostatin analog therapy) | 117 | 14.51 | 34.8 |

| Patients with vascular diseases (mesenteric vascular failure, mesenteric ischemia) | 117 | 12.09 | 35.1 |

| Scale | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| MUST | 122 | 78.21 |

| MNA-SF | 50 | 32.05 |

| NRS-2002 | 28 | 17.95 |

| CONUT | 15 | 9.62 |

| GLIM | 6 | 3.85 |

| Other | 20 | 12.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diéguez Castillo, C.; Sidahi Serrano, M.; Martín Aguilar, A.; De Luis Román, D. Use of Oligomeric Formulas in Malabsorption: A Delphi Study and Consensus. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1426. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091426

Diéguez Castillo C, Sidahi Serrano M, Martín Aguilar A, De Luis Román D. Use of Oligomeric Formulas in Malabsorption: A Delphi Study and Consensus. Nutrients. 2025; 17(9):1426. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091426

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiéguez Castillo, Carmelo, Maryam Sidahi Serrano, Andrea Martín Aguilar, and Daniel De Luis Román. 2025. "Use of Oligomeric Formulas in Malabsorption: A Delphi Study and Consensus" Nutrients 17, no. 9: 1426. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091426

APA StyleDiéguez Castillo, C., Sidahi Serrano, M., Martín Aguilar, A., & De Luis Román, D. (2025). Use of Oligomeric Formulas in Malabsorption: A Delphi Study and Consensus. Nutrients, 17(9), 1426. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17091426