Understanding Barriers to Health Behaviours in 13–17-Year-Olds: A Whole Systems Approach in the Context of Obesity

Highlights

- A Whole Systems Approach in a local context provided a strategy to explore both the experiences of key stakeholders working with young people and the authentic voice of young people.

- Youth service providers reported a lack of training and support and a lack of confidence discussing weight management with young people, in contrast to their familiarity dealing with mental health issues.

- Young people identified a range of barriers and facilitators to healthy lifestyles; however, there was a pervasive influence of health inequalities that affected how they were treated and the healthy options available to them. Inequalities related specifically to money, geography, and gender.

- The Whole Systems Approach offered a means to characterise the complex interactions that underpin adolescent obesity in Surrey and highlight the need to address inequalities and foster supportive environments to facilitate healthier choices.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study 1: The Stakeholders’ Voice: A Survey

2.1. Method

Design

- -

- Quantitative Component

- -

- Qualitative Component

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Results

3. Study 2: The Young Person’s Voice: Focus Groups

3.1. Participants

3.2. Design

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

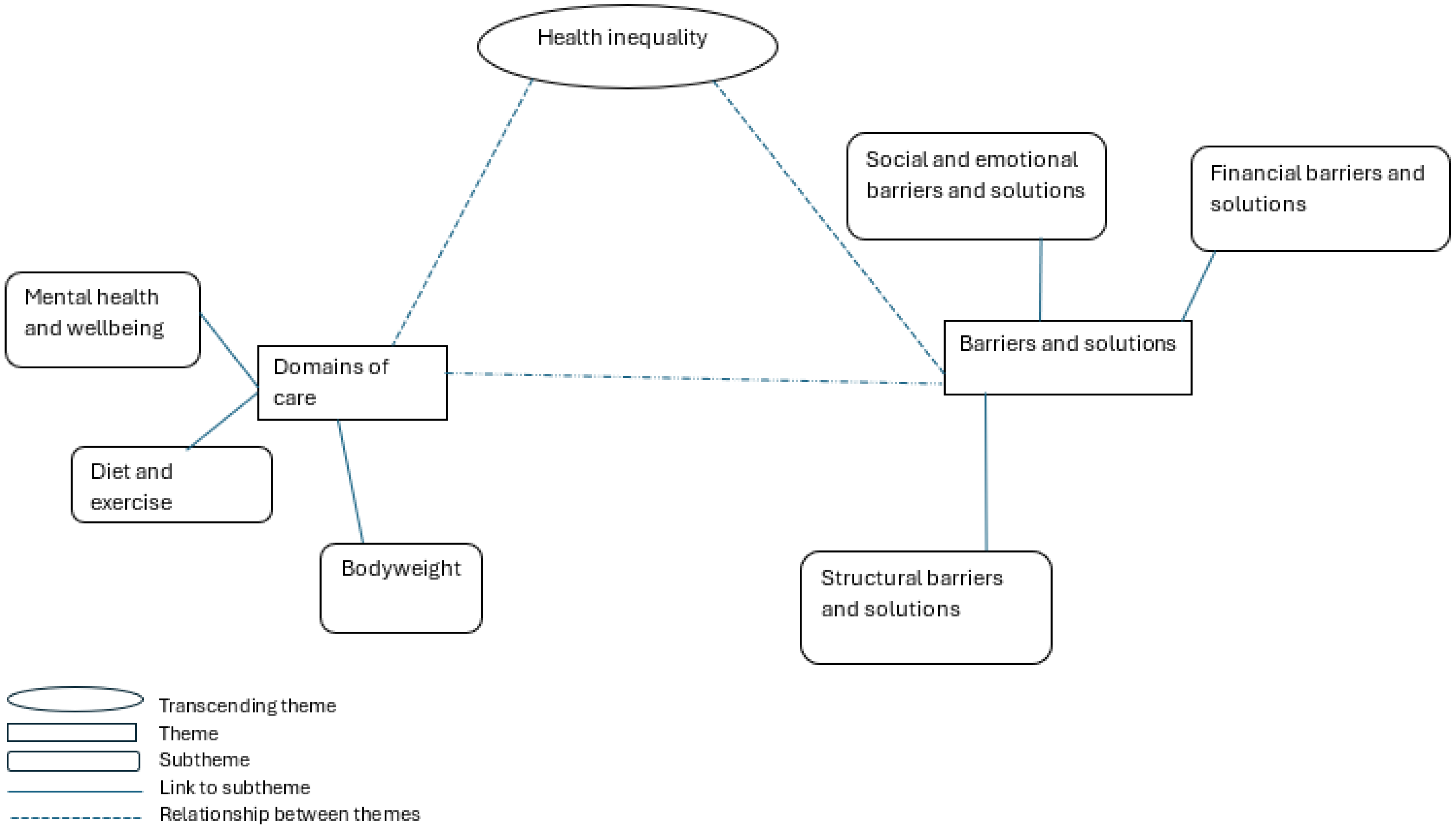

4.1. Theme 1: Domains of Care

- (i)

- Diet and exercise

“So, if you’ve got healthy things in the fridge, you eat healthy, and if not, you’re hungry, so you eat what’s in there.”

“My stepdad honestly he gives me too many sweets when I’m, whenever I’m playing games on my xx. So I mean, like he would probably be the worst reason why I eat sweets and chocolate the worst.”

“As long as your coach is good and supports you it doesn’t matter your gender as long as they know what they are doing and support you, encourage you.”

- (ii)

- Body weight

“I feel insecure about my weight and like…How big my belly is, but really like nothing ever gets said about it. So, I don’t know if that’s actually that bad.”

“The thing is you can’t. You can’t be too skinny because then you could be called anorexic. But you can’t be too fat because you’d be called, you’d you’d be called fat. But then at the same time, you can’t want to be skinny.”

“The internet, it’s so bad with like body image and how you look, what you eat…makes you feel so bad about yourself when you’re trying your hardest and you see all these people with perfect bodies.”

“If I was really overweight, there’d be a warning like, ‘We’ll drop you if you don’t lose weight.’ So, then I’ll just go to them and say, ’Set me a diet then’.”

“Oh, cause then if you’re like severely obese and you play for a club, they’re not gonna want to play you because you won’t be the best player if you’re not fit. Yeah. So, then you’d be like, ‘How do you want me to get fit?’ And then they could just take you on fitness plans and a diet.”

- (iii)

- Mental health and wellbeing

“Like I said, all they [the teachers] were saying is ‘ohh just ignore them. [the bullies] Try to not do anything with them and like, try stay away from them’, but it’s really hard to do that, yeah and like you can say that, but that’s that’s never ever gonna help and also, people if you’re getting angry or sad, people might say ‘ohh take a chill pill, calm down’, but that never actually helps. Yeah they might not. They might not know that, but it literally never helps so I mean, I’m just saying that.”

“I think school as a whole can make people stress a lot like if you get give them too much and work. Then you could get too stressed or if you get if you have a test or a quiz that you’re not quite prepared for soon, then you might be like ‘ohh, what if this happens? What if that happens?’ Well, if I get a bad grade what if my parents are disappointed in me or something? And then like all the stress just builds up from every single bit of School and then like you have to release it some way, so it might also come out as you becoming a bully at school or being a bad person at school.”

“The thing is she [the school counsellor]. She’s like. I don’t trust her anymore because she left me in her room for half an hour with the door wide open by myself. Like. Literally crying my eyes out and she just left me like that. You don’t gain students trust from it. You gain like you don’t gain anything from it and there is like your job here is to be a supporter, to a student, but you’re not supporting them at all.”

“I feel like sometimes it is like, oh, there’s this and this that could happen. Like, if you’re feeling slightly anxious then and it’s sometimes I feel like it is overdone a little bit.”

4.2. Theme 2: Barriers and Solutions

- (i)

- Financial barriers and solutions

“I could get a full Tesco meal Deal for it and still have money left over. But in school you get like half a slice of bread.”

“School food is really overpriced.”

“Like at times you can’t do much because you don’t have the money to or it’s too expensive. Like there’s so many opportunities that so many people want to do. But it’s too expensive because like they obviously can’t really drop the price because they’ve got to earn a living off of it. But at the same time for people to go, it needs to be cheaper because it only seems like the people who have the have the amount of money that could go.”

- (ii)

- Structural barriers and solutions

“Sometimes the school meals I feel are a bit like these aren’t very healthy.”

“They’re [school dinners] not great. The quality of the food is really not brilliant so it’s like all terrible.”

“If you don’t like football, there’s really nothing else to do. It would be nice to have more options.”

“It’s scary walking to the park at night. I’d rather stay home than risk crossing dark streets.”

“I wish I knew more about what sports I could join. I feel like there are a lot of options, but I just don’t know about them.”

“But even mental health service like CAMHS, like CAMHS in horrendous. You’re on the waiting list for two years, unless you’re, like, severely, severely depressed, suicidal. And they put you on the like the red zone. And as soon as they think. Ohh yeah, you’re good. They’ll take you off it and put you back on the waiting list and never see you again. And like they just don’t get you help. It’s not good.”

“When I walk around and see litter everywhere, it just makes me feel stressed and unhappy. It’s like no one cares.”

- (iii)

- Social and emotional barriers and solutions

“I makes you not want to do it, cause if they’re rude to you and don’t encourage you then you just want to give up on the sport and leave.”

“You get made fun of for asking for help when you need it.”

“You would be really embarrassed, and they would tease you about that and then you might become the bully.”

“CAHMS is great when you can get help, but the waiting lists are so long. It’s like the support isn’t there when you actually need it.”

4.3. Transcending Theme: Health Inequality

“Yeah, like big families and all that. Like at times you can’t do much because you don’t have the money to or it’s too expensive. Like there’s so many opportunities that so many people want to do. But it’s too expensive because they obviously can’t really drop the price because they’ve got to earn a living off of it. But at the same time for people to go, it needs to be cheaper because it only seems like the people who have the have the amount of money that couldn’t go.”

“More lights around, like the park area because it gets like pitch it’s pitch black and you have to like walk through the park.”

“More lights cause I know on my street like this lady’s car got vandalised like a couple of times. But I think it’s been so dark, but because the lights turn off so early, they can’t actually see who’s doing it on the cameras.”

“Boys are so horrible to anybody else that plays sport. They’re always like, they’re always but they’re always like, oh, you look like a man or you’re a man for doing that. They’re like, take the mick out of you for playing a boys sport. If it’s a boy dominated sport, they’re like you’re not like you’re a lesbian.”

5. Discussion

5.1. Study 1: The Stakeholders’ Voice

5.2. Study 2: Young People’s Voice

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Department of Health and Social Care. Public Health Profiles. Fingertips. 2019. Available online: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Simmonds, M.; Llewellyn, A.; Owen, C.G.; Woolacott, N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2016, 17, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childhood Obesity: A Plan for Action. GOV.UK. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/childhood-obesity-a-plan-for-action (accessed on 20 January 2017).

- Public Health England. The Wellbeing of 15-Year-Olds: Analysis of the 2014 What About Youth? Survey. 2014. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-wellbeing-of-15-year-olds-analysis-of-the-what-about-youth-survey (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. National Diet and Nutrition Survey. 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/announcements/national-diet-and-nutrition-survey-2019-to-2023 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Dietz, W.H. Critical periods in childhood for the development of obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1994, 59, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellis, M.A.; Hughes, K.; Leckenby, N.; Perkins, C.; Lowey, H. National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooley, B.A.; Fitzgerald, A. My World Survey: National Study of Youth Mental Health in Ireland; Headstrong and UCD School of Psychology: Dublin, Ireland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- NHS England. Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2023-Wave 4 Follow up to the 2017 Survey. NHS England Digital. 2023. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2023-wave-4-follow-up (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Oellingrath, I.M.; Svendsen, M.V.; Hestetun, I. Eating patterns and mental health problems in early adolescence—A cross-sectional study of 12–13-year-old Norwegian schoolchildren. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2554–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shawon, M.S.R.; Rouf, R.R.; Jahan, E.; Hossain, F.B.; Mahmood, S.; Gupta, R.D.; Islam, M.I.; Al Kibria, G.M.; Islam, S. The burden of psychological distress and unhealthy dietary behaviours among 222,401 school-going adolescents from 61 countries. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodega, P.; de Cos-Gandoy, A.; Fernández-Alvira, J.M.; Fernández-Jiménez, R.; Moreno, L.A.; Santos-Beneit, G. Body image and dietary habits in adolescents: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2023, 82, 104–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitratos, S.M.; Swartz, J.R.; Laugero, K.D. Pathways of parental influence on adolescent diet and obesity: A psychological stress–focused perspective. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1800–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Hample, D. Modeling Parental Influence on Teenagers’ Food Consumption: An Analysis Using the Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) Survey. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, E.L.; Timmer, A. Children’s and adolescents’ characteristics and interactions with the food system. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 27, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.; Muir, S.; Strömmer, S.; Crozier, S.; Cooper, C.; Smith, D.; Barker, M.; Vogel, C. The interplay between social and food environments on UK adolescents’ food choices: Implications for policy. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, daad097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, S. Is There an Inter-Relationship Between Mental Wellbeing and Lifestyle Practices (Specifically Diet and Physical Activity Level) in Adolescents? A Systematic Review. Unpublished. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- King, E. The Role of Sleep in Obesity Among Adolescents. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Studies. Unpublished. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil, A.; Quirk, S.E.; Housden, S.; Brennan, S.L.; Williams, L.J.; Pasco, J.A.; Berk, M.; Jacka, F.N. Relationship Between Diet and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e31–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C.M.; Hardy-Johnson, P.L.; Inskip, H.M.; Morris, T.; Parsons, C.M.; Barrett, M.; Hanson, M.; Woods-Townsend, K.; Baird, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions with health education to reduce body mass index in adolescents aged 10 to 19 years. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moores, C.J.; Bell, L.K.; Miller, J.; Damarell, R.A.; Matwiejczyk, L.; Miller, M.D. A systematic review of community-based interventions for the treatment of adolescents with overweight and obesity. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 698–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, G.; Fakoya, O.; Wills, W.; Lloyd, N.; Bontoft, C.; Wellings, A.; Harding, S.; Jackson, J.; Barrett, K.; Wagner, A.P.; et al. Whole systems approaches to diet and healthy weight: A scoping review of reviews. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0292945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagnall, A.M.; Radley, D.; Jones, R.; Gately, P.; Nobles, J.; Van Dijk, M.; Blackshaw, J.; Montel, S.; Sahota, P. Whole systems approaches to obesity and other complex public health challenges: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radley, D. Whole Systems Approach to Obesity. A Guide to Support Local Approaches to Promoting a Healthy Weight; Public Health England: Harborne, UK, 2019.

- Pettican, A.; Southall-Edwards, R.; Reinhardt, G.Y.; Gladwell, V.; Freeman, P.; Low, W.; Copeland, R.; Mansfield, L. Tackling physical inactivity and inequalities: Implementing a whole systems approach to transform community provision for disabled people and people with long-term health conditions. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reece, L.; Bauman, A.; Nau, T.; Lee, K.; Smith, B.J.; Bellew, W.; McCue, P.; Hamdorf, P.; Shearn, K.; Lowe, A.; et al. Translating whole system approaches into practice to increase population physical activity: Symposium A6. Health Fit. J. Can. 2021, 14, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Surrey Heath Borough Council. Annual Plan 2023-24—Q2 Update; Surrey Heath Borough Council: Camberly, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Be Your Best Surrey. Available online: https://www.bybsurrey.org/ (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Science, Innovation and Technology. New Online Safety Priorities for Ofcom and Launch of Study into Effects of Social Media on Children. GOV.UK. 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-online-safety-priorities-for-ofcom-and-launch-of-study-into-effects-of-social-media-on-children (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Kanellopoulou, A.; Vassou, C.; Kornilaki, E.N.; Notara, V.; Antonogeorgos, G.; Rojas-Gil, A.P.; Lagiou, A.; Yannakoulia, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B. The Association between Stress and Children’s Weight Status: A School-Based, Epidemiological Study. Children 2022, 9, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, A.; Green, J.M.; Williams, V.; McLeish, J.; McCormick, F.; Fox-Rushby, J.; Renfrew, M.J. Can food vouchers improve nutrition and reduce health inequalities in low-income mothers and young children: A multi-method evaluation of the experiences of beneficiaries and practitioners of the Healthy Start programme in England. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, J.; Colquhoun, D. The relationship between policy and place: The role of school meals in addressing health inequalities. Health Sociol. Rev. 2009, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowler, E.; Turner, S.; Dobson, B. Poverty Bites: Food, Health and Poor Families; Child Action Poverty Group: Drumchapel, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, P.; Chamberlin, R. Improving the Take Up of Free School Meals; DfEE: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Craggs, C.; Corder, K.; Van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Griffin, S.J. Determinants of Change in Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhl, R.M.; Lessard, L.M. Weight Stigma in Youth: Prevalence, Consequences, and Considerations for Clinical Practice. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2020, 9, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessard, L.M.; Puhl, R.M. Adolescents’ exposure to and experiences of weight stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 46, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garside, R.; Pearson, M.; Hunt, H.; Moxham, T.; Anderson, R. Identifying the Key Elements and Interactions of a Whole System Approach to Obesity Prevention; Peninsula Technology Assessment Group (PenTAG): Exeter, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Topic | Items |

|---|---|

| Healthy eating | What challenges do you face in supporting young people to make healthier eating choices? What would help you to support young people with making healthier eating choices better? |

| Physical activity | What challenges do you face in supporting young people to be physically active? What would help you support young people with their physical activity better? |

| Weight management | What challenges do you face in supporting young people with weight management? What would help you support young people with weight management better? |

| Mental health | What challenges do you face in supporting young people with their mental health? What would help you support young people with their mental health better? |

| Wellbeing | What challenges do you face in supporting young people with their wellbeing? What would help you support young people with their wellbeing better? |

| General | Can you think of anything else that might help you support young people’s health? |

| Theme | Subthemes Explored | Verbatim Example | Freq of Theme | Theme Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Lack of training (youth leader) | “Education establishments to offer more training opportunities for staff to feel more confident on delivering certain topics” | 30 (22%) | 37 (28%) |

| Lack of knowledge (youth leader) | “Would like to be knowledgeable” “Lack of knowledge on how to support weight management without causing harm” | 7 (5%) | ||

| Environment | School Environment | “Better/healthier options in the canteen” “More varied meals in the canteen” | 5 (4%) | 20 (15%) |

| Food Environment (availability, price) | “What is readily available to young people (e.g., energy drinks, cheap processed foods)” “Food on offer on-site” “Increased availability and lower costs of healthier foods” | 9 (7%) | ||

| Social media | “Social media and marketing companies pushing unhealthy food on our children” “Screens, internet and social media provide unhealthy habits and content” | 2 (1.5%) | ||

| Government (NHS) | “Little support from NHS” “More joined up work between local NHS services i.e., dieticians, GP surgeries” “Culture of eating ultra-processed foods is endemic, and requires policy change and governmental intervention” | 4 (3%) | ||

| Support | Parental support | “Require parents to provide a variety of alternatives” | 3 (2%) | 22 (16%) |

| External support (nutritionists/GPs) | “More training/education from experts for the kids” “Talks in school” “External speakers and workshops for young people” “Input from dietitian specialists in college—a drop in, or tutorial session for students, a training session for staff” | 8 (6%) | ||

| Pathway of support | “More access to signposting” “An easier/central way of finding out what is available in the local area and how to access these services” “A lack of clear pathway and process for school nurses to follow” “A clear pathway to follow … when to refer to other services” “Better knowledge of available services in the areas I’m working” | 11 (8%) | ||

| Resources | Lack of financial resources | “More funding for our catering team to put on regular healthy eating days throughout the year” “More funding for events and training” “Sufficient funding to support small groups on a regular and recurring basis” “More funding for activity opportunities” “More incentives for teenagers to continue with the physical activity” | 7 (5%) | 36 (27%) |

| Lack of practical resources | “Short, snappy resources to hand out” “Readily available resources” “Basic visual resources” “Limited age-appropriate resources” “Better websites/agencies to signpost to” | 20 (15%) | ||

| Education | Lack of education for young people | “There is a lack of education as to what ‘healthy’ eating is” “A drop-in or tutorial session for students” “Earlier education at school” “Ability for more children to understand why activity is good for you” | 15 (11%) | 19 (14%) |

| Lack of education for parents | “Education to families as to the benefits of physical activity, eating healthy and sleep.” “More parent education classes/workshops to improve their knowledge” “Too many options and families who don’t understand the benefits of eating healthy” | 4 (3%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lambert, H.; Engel, B.; Hart, K.; Ogden, J.; Penfold, K. Understanding Barriers to Health Behaviours in 13–17-Year-Olds: A Whole Systems Approach in the Context of Obesity. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1312. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17081312

Lambert H, Engel B, Hart K, Ogden J, Penfold K. Understanding Barriers to Health Behaviours in 13–17-Year-Olds: A Whole Systems Approach in the Context of Obesity. Nutrients. 2025; 17(8):1312. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17081312

Chicago/Turabian StyleLambert, Helen, Barbara Engel, Kathryn Hart, Jane Ogden, and Katy Penfold. 2025. "Understanding Barriers to Health Behaviours in 13–17-Year-Olds: A Whole Systems Approach in the Context of Obesity" Nutrients 17, no. 8: 1312. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17081312

APA StyleLambert, H., Engel, B., Hart, K., Ogden, J., & Penfold, K. (2025). Understanding Barriers to Health Behaviours in 13–17-Year-Olds: A Whole Systems Approach in the Context of Obesity. Nutrients, 17(8), 1312. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17081312