Higher Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods Is Associated with Lower Plant-Based Diet Quality in Australian Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Dietary Assessment

2.3. Plant-Based Diet Quality

2.4. UPFs Classification

2.5. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

3.2. UPFs and PDI, hPDI and uPDI

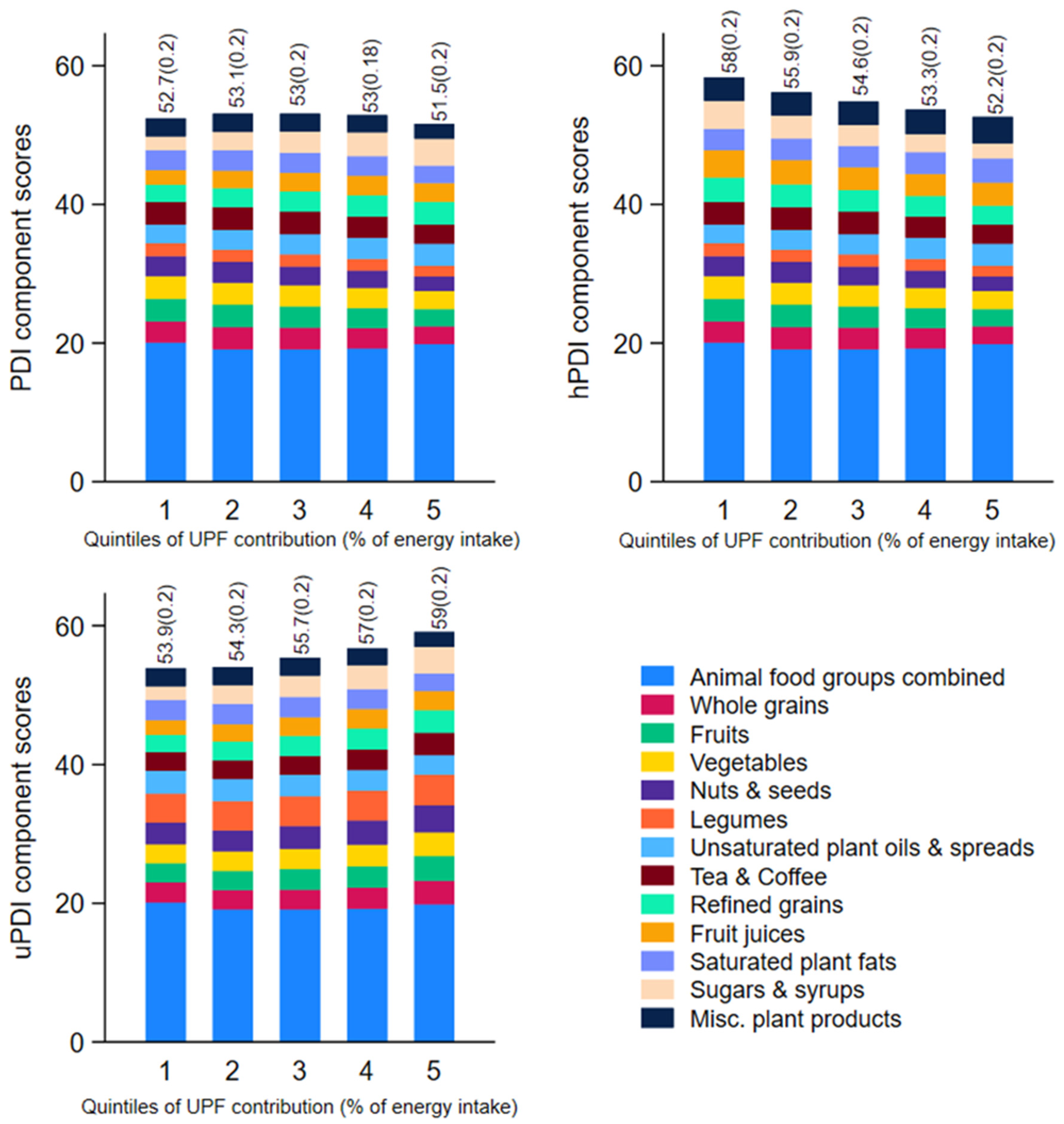

3.2.1. Intake of Plant-Based Diet Quality Components and UPFs

3.2.2. Association Between UPFs and PDI, hPDI, and uPDI

3.2.3. Association Between UPFs and Component Scores

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | American Cancer Society diet score |

| AUSNUT | Australian Food and Nutrient Database |

| CI | confidence interval |

| FFQ | Food Frequency Questionnaire |

| hPDI | healthy Plant-based Diet Index |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| NNPAS | National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey |

| PBD | plant-based diet |

| PDI | Plant-based Diet Index |

| Q | quintile |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SE | standard error |

| SEM | standard error measure |

| SSB | sugar-sweetened beverages |

| uPDI | unhealthy Plant-based Diet Index |

| UPFs | ultra-processed foods |

| UK | the United Kingdom |

| USA | the United States of America |

References

- Hargreaves, S.M.; Rosenfeld, D.L.; Moreira, A.V.B.; Zandonadi, R.P. Plant-based and vegetarian diets: An overview and definition of these dietary patterns. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kent, G.; Kehoe, L.; Flynn, A.; Walton, J. Plant-based diets: A review of the definitions and nutritional role in the adult diet. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.A.; Patel, H. Healthy Plant-Based Diet: What Does it Really Mean? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dinu, M.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3640–3649. [Google Scholar]

- Dybvik, J.S.; Svendsen, M.; Aune, D. Vegetarian and vegan diets and the risk of cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease and stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Salehin, S.; Rasmussen, P.; Mai, S.; Mushtaq, M.; Agarwal, M.; Hasan, S.M.; Salehin, S.; Raja, M.; Gilani, S.; Khalife, W.I. Plant based diet and Its effect on cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3337. [Google Scholar]

- Marchese, L.E.; McNaughton, S.A.; Hendrie, G.A.; Wingrove, K.; Dickinson, K.M.; Livingstone, K.M. A scoping review of approaches used to develop plant-based diet quality indices. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2023, 7, 100061. [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasinghe, K.; Breda, J.; Berdzuli, N.; Rippin, H.; Farrand, C.; Halloran, A. The shift to plant-based diets: Are we missing the point? Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 29, 100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Frontier. The Food Frontier Consumer Survey 2024 Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.foodfrontier.org/resource/food-frontier-consumer-survey/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Du, S.; Ashtree, D.N.; McGuinness, A.J.; Gauci, S.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Srour, B.; et al. Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ 2024, 384, e077310. [Google Scholar]

- Curtain, F.; Grafenauer, S. Plant-based meat substitutes in the flexitarian age: An audit of products on supermarket shelves. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nájera Espinosa, S.; Hadida, G.; Jelmar Sietsma, A.; Alae-Carew, C.; Turner, G.; Green, R.; Pastorino, S.; Picetti, R.; Pauline, S. Mapping the evidence of novel plant-based foods: A systematic review of nutritional, health, and environmental impacts in high-income countries. Nutr. Rev. 2024, nuae031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sadig, R.; Wu, J. Are novel plant-based meat alternatives the healthier choice? Food Res. Int. 2024, 183, 114184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A. Perspective: Identifying ultra-processed plant-based milk alternatives in the USDA branded food products database. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 2068–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, K.M.; Neumann, N.J.; Fasshauer, M. Ultra-processing markers are more prevalent in plant-based meat products as compared to their meat-based counterparts in a German food market analysis. Public. Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 2728–2737. [Google Scholar]

- Vellinga, R.E.; Rippin, H.L.; Gonzales, B.G.; Temme, E.H.M.; Farrand, C.; Halloran, A.; Clough, B.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Santos, M.; Fontes, T.; et al. Nutritional composition of ultra-processed plant-based foods in the out-of-home environment: A multi-country survey with plant-based burgers. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 131, 1691–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, A.; Mueller, M.; Schneider, I.; Hahn, A. Application of a modified Healthy Eating Index (HEI-Flex) to compare the diet quality of flexitarians, vegans and omnivores in Germany. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, J.; Touvier, M.; Baudry, J.; Julia, C.; Buscail, C.; Srour, B.; Hercberg, S.; Péneau, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B. Consumption of ultra-processed foods by pesco-vegetarians, vegetarians, and vegans: Associations with duration and age at diet initiation. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Donoso, C.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Gea, A.; Murphy, K.J.; Parletta, N.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. A food-based score and incidence of overweight/obesity: The Dietary Obesity-Prevention Score (DOS). Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 2607–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Caulfield, L.E.; Rebholz, C.M. Healthy plant-based diets are associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality in US adults. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.L.; Chantaprasopsuk, S.; Islami, F.; Rees-Punia, E.; Um, C.Y.; Wang, Y.; Leach, C.R.; Sullivan, K.R.; Patel, A.V. Association of socioeconomic and geographic factors with diet quality in US adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2216406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meyer, K.A.; Sijtsma, F.P.; Nettleton, J.A.; Steffen, L.M.; Van Horn, L.; Shikany, J.M.; Gross, M.D.; Mursu, J.; Traber, M.G.; Jacobs, D.R. Dietary patterns are associated with plasma F2-isoprostanes in an observational cohort study of adults. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 57, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohlau, M.; Spiller, A.; Risius, A. Plant-based diets are not enough? Understanding the consumption of plant-based meat alternatives along ultra-processed foods in different dietary patterns in Germany. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 852936. [Google Scholar]

- Salomé, M.; Arrazat, L.; Wang, J.; Dufour, A.; Dubuisson, C.; Volatier, J.-L.; Huneau, J.-L.; Mariotti, F. Contrary to ultra-processed foods, the consumption of unprocessed or minimally processed foods is associated with favorable patterns of protein intake, diet quality and lower cardiometabolic risk in French adults (INCA3). Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 4055–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satija, A.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Rimm, E.B.; Spiegelman, D.; Chiuve, S.E.; Borgi, L.; Willett, W.C.; Manson, J.E.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B. Plant-based dietary patterns and Incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: Results from three prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotos-Prieto, M.; Struijk, E.A.; Fung, T.T.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B.; Lopez-Garcia, E. Association between the quality of plant-based diets and risk of frailty. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 2854–2862. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, S.J.; Gallagher, C.; Elliott, A.D.; E Bradbury, K.; Marcus, G.M.; Linz, D.; Pitman, B.M.; E Middeldorp, M.; Hendriks, J.M.; Lau, D.H.; et al. Associations of dietary patterns, ultra-processed food and nutrient intake with incident atrial fibrillation. Heart 2023, 109, 1683–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.; Parnham, J.C.; Rauber, F.; Levy, R.B.; Huybrechts, I.; Gunter, M.J.; Millett, C.; Vamos, E.P. Plant-based dietary patterns and ultra-processed food consumption: A cross-sectional analysis of the UK Biobank. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 78, 102931. [Google Scholar]

- Torquato, B.M.d.A.; Madruga, M.; Levy, R.B.; da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Rauber, F. The share of ultra-processed foods determines the overall nutritional quality of diet in British vegetarians. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 132, 616–623. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4363.0.55.001—Australian Health Survey: Users’ Guide, 2011-13. 2013. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4363.0.55.001Main+Features12011-13 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Nutrition First Results—Foods and Nutrients. 2011. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/australian-health-survey-nutrition-first-results-foods-and-nutrients/latest-release (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Nutrition across the Life Stages. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2018. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/food-nutrition/nutrition-across-the-life-stages (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, New Zealand Ministry of Health. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2006. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/nutrient-reference-values-australia-and-new-zealand-including-recommended-dietary-intakes (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Lachat, C.; Hawwash, D.; Ocké, M.C.; Berg, C.; Forsum, E.; Hörnell, A.; Larsson, C.L.; Sonestedt, E.; Wirfält, E.; Åkesson, A.; et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology—nutritional epidemiology (STROBE-nut): An extension of the STROBE statement. Nutr. Bull. 2016, 41, 240–251. [Google Scholar]

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. AUSNUT 2011–2013—Food Composition Database. 2014. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science-data/food-composition-databases/ausnut (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Stanford, J.; McMahon, S.; Lambert, K.; Charlton, K.E.; Stefoska-Needham, A. Expansion of an Australian food composition database to estimate plant and animal intakes. Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 130, 1950–1960. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stanford, J.; Stefoska-Needham, A.; Lambert, K.; Batterham, M.J.; Charlton, K. Association between plant-based diet quality and chronic kidney disease in Australian adults. Public. Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, P.P.; Steele, E.M.; Levy, R.B.; Sui, Z.; Rangan, A.; Woods, J.; Gill, T.; Scrinis, G.; Monteiro, C.A. Ultra-processed foods and recommended intake levels of nutrients linked to non-communicable diseases in Australia: Evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029544. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W.C.; Howe, G.R.; Kushi, L.H. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65, 1220S–1228S. [Google Scholar]

- Cacau, L.T.; Souza, T.N.; Louzada, M.L.d.C.; Marchioni, D.M.L. Adherence to the EAT-Lancet sustainable diet and ultra-processed food consumption: Findings from a nationwide population-based study in Brazil. Public. Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Moubarac, J.C.; Levy, R.B.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Jaime, P.C. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Puppo, F.; Del Bo’, C.; Vinelli, V.; Riso, P.; Porrini, M.; Martini, D. A systematic review of worldwide consumption of ultra-processed foods: Findings and criticisms. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Srebot, S.; Ahmed, M.; Mulligan, C.; Hu, G.; L’Abbé, M.R. Nutritional quality and price of plant-based dairy and meat analogs in the Canadian food supply system. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 3594–3606. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, D.; Singh, S.; Seah, J.S.H.; Yeo, D.C.L.; Tan, L.P. Commercialization of plant-based meat alternatives. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 1055–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Morach, B.; Witte, B.; Walker, D.; von Koeller, E.; Grosse-Holz, F.; Rogg, J.; Brigl, M.; Dehnert, N.; Obloj, P.; Koktenturk, S.; et al. Food for Thought: The Protein Transformation. Boston Consulting Group. 2021. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2021/the-benefits-of-plant-based-meats (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Baker, P.; Machado, P.; Santos, T.; Sievert, K.; Backholer, K.; Hadjikakou, M.; Russell, C.; Huse, O.; Bell, C.; Scrinis, G.; et al. Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes Rev. 2020, 21, e13126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy-Nichols, J.; Hattersley, L.; Scrinis, G. Nutritional marketing of plant-based meat-analogue products: An exploratory study of front-of-pack and website claims in the USA. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 4430–4441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marchese, L.; Livingstone, K.M.; Woods, J.L.; Wingrove, K.; Machado, P. Ultra-processed food consumption, socio-demographics and diet quality in Australian adults. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Machado, P.; McNaughton, S.A.; Wingrove, K.; Stephens, L.D.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M. A Scoping Review of the Causal Pathways and Biological Mechanisms Linking Nutrition Exposures and Health Outcomes. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2024, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Srour, B.; Kordahi, M.C.; Bonazzi, E.; Deschasaux-Tanguy, M.; Touvier, M.; Chassaing, B. Ultra-processed foods and human health: From epidemiological evidence to mechanistic insights. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization & Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nation. Sustainable Healthy Diets: Guiding Principles; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/329409 (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Marchese, L.E.; Hendrie, G.A.; McNaughton, S.A.; Brooker, P.G.; Dickinson, K.M.; Livingstone, K.M. Comparison of the nutritional composition of supermarket plant-based meat and dairy alternatives with the Australian Food Composition Database. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 129, 106017. [Google Scholar]

- Rauber, F.; Louzada, M.L.d.C.; Chang, K.; Huybrechts, I.; Gunter, M.J.; Monteiro, C.A.; Vamos, E.P.; Levy, R.B. Implications of food ultra-processing on cardiovascular risk considering plant origin foods: An analysis of the UK Biobank cohort. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 43, 100948. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova, R.; Viallon, V.; Fontvieille, E.; Peruchet-Noray, L.; Jansana, A.; Wagner, K.-H.; Kyrø, C.; Tjønneland, A.; Katzke, V.; Bajracharya, R.; et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and risk of multimorbidity of cancer and cardiometabolic diseases: A multinational cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2023, 35, 100771. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, D.; Godos, J.; Bonaccio, M.; Vitaglione, P.; Grosso, G. Ultra-Processed Foods and Nutritional Dietary Profile: A Meta-Analysis of Nationally Representative Samples. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Dodd, K.W.; Guenther, P.M.; Freedman, L.S.; Subar, A.F.; Kipnis, V.; Midthune, D.; Tooze, J.A.; Krebs-Smith, S.M. Statistical methods for estimating usual intake of nutrients and foods: A review of the theory. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1640–1650. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Plant-Based Diet Quality Index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | p Trend | |

| PDI | ||||||

| n ^ (% weight adjusted) | 1977 (21.3) | 1984 (21.9) | 1692 (18.5) | 1806 (19.7) | 1652 (18.6) | |

| PDI score | 44 (0.08) | 49.6 (0.03) | 53 (0.03) | 56.4 (0.04) | 62.1 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Energy intake (kcal/d) | 1744 (24.8) | 1861 (25.2) | 1953 (26.5) | 2178 (27.8) | 2320 (28.0) | <0.001 |

| UPF intake (%E) ^^ | 41.0 (0.7) | 40.3 (0.7) | 37.7 (0.7) | 39.5 (0.7) | 36.3 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Age, y | 45.2 (0.5) | 46.3 (0.5) | 47.3 (0.6) | 46.6 (0.6) | 48.3 (0.6) | 0.002 |

| Female, % | 51.3 | 49.2 | 51.3 | 49.2 | 45.7 | 0.095 |

| Education & | ||||||

| Low, % | 28.2 | 27.4 | 29.3 | 22.3 | 21.5 | <0.001 |

| Medium, % | 50.2 | 50.0 | 46.1 | 51.3 | 47.7 | |

| High, % | 21.6 | 22.6 | 24.6 | 26.4 | 30.9 | |

| Country of birth < | ||||||

| Australia, % | 73.3 | 66.2 | 69.5 | 68.5 | 66.4 | 0.003 |

| English-speaking, % | 11.6 | 13.1 | 10.9 | 10.8 | 11.4 | |

| Other, % | 15.1 | 20.7 | 19.5 | 20.7 | 22.2 | |

| Rurality | ||||||

| Major city, % | 68.9 | 74.3 | 69.8 | 71.1 | 73.7 | 0.016 |

| Inner regional, % | 19.8 | 17.3 | 19.7 | 20.1 | 18.9 | |

| Other, % | 11.4 | 8.4 | 10.5 | 8.8 | 7.4 | |

| Area-level disadvantage $ | ||||||

| First quintile *, % | 21.2 | 17.1 | 17.4 | 19.1 | 15.6 | 0.193 |

| Third quintile, % | 20.6 | 20.0 | 20.7 | 21.2 | 21.0 | |

| Fifth quintile **, % | 19.6 | 23.3 | 22.2 | 22.2 | 24.8 | |

| hPDI | ||||||

| n ^ (% weight adjusted) | 2078 (24.2) | 1773 (20.1) | 1860 (20.3) | 1599 (16.8) | 1801 (18.5) | |

| hPDI score | 45 (0.1) | 52 (0.04) | 56 (0.03) | 59 (0.04) | 66 (0.12) | <0.001 |

| Energy intake (kcal/d) | 2397 (27) | 2063 (27) | 1922 (26) | 1773 (24) | 1709 (24) | <0.001 |

| UPF intake (%E) ^^ | 46.1 (0.6) | 41.6 (0.7) | 39.0 (0.7) | 34.9 (0.7) | 30.8 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Age, y | 40.7 (0.5) | 44.8 (0.5) | 48.2 (0.6) | 49.7 (0.6) | 52.1 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Female, % | 40.8 | 46.6 | 49.3 | 55.0 | 58.6 | <0.001 |

| Education & | ||||||

| Low, % | 23.2 | 24.4 | 27.0 | 27.5 | 27.9 | <0.001 |

| Medium, % | 51.5 | 49.9 | 51.4 | 48.5 | 43.3 | |

| High, % | 25.3 | 25.7 | 21.6 | 24.1 | 28.8 | |

| Country of birth < | ||||||

| Australia, % | 70.6 | 71.3 | 69.7 | 71.9 | 74.7 | 0.190 |

| English-speaking, % | 20.0 | 19.4 | 20.1 | 18.5 | 17.2 | |

| Other, % | 9.4 | 9.2 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 8.1 | |

| Rurality | ||||||

| Major city, % | 70.6 | 71.3 | 69.7 | 71.9 | 74.7 | 0.425 |

| Inner regional, % | 20.0 | 19.4 | 20.1 | 18.5 | 17.2 | |

| Other, % | 9.4 | 9.2 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 8.1 | |

| Area-level disadvantage $ | ||||||

| First quintile *, % | 19.3 | 17.7 | 17.7 | 17.8 | 17.7 | 0.761 |

| Third quintile, % | 21.0 | 22.0 | 20.4 | 20.5 | 19.3 | |

| Fifth quintile **, % | 21.8 | 21.4 | 20.9 | 24.5 | 23.8 | |

| uPDI | ||||||

| n ^ (% weight adjusted) | 2057(21.7) | 1859 (20.3) | 1992 (21.1) | 1663 (18.4) | 1540 (18.5) | |

| uPDI score | 46.5 (0.09) | 52.6 (0.04) | 56.5 (0.03) | 60.4 (0.04) | 66.2 (0.11) | <0.001 |

| Energy intake (kcal/d) | 2320 (25) | 2109 (26) | 1979 (25.4) | 1813 (27) | 1719 (28) | <0.001 |

| UPF intake (%E) ^^ | 29.8 (0.5) | 36.9 (0.6) | 40.0 (0.6) | 43.0 (0.8) | 47.2 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Age, y | 50.6 (0.5) | 48.5 (0.5) | 47.4 (0.5) | 45.4 (0.6) | 40.7 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Female, % | 51.1 | 47.0 | 49.6 | 49.3 | 49.8 | 0.447 |

| Education & | ||||||

| Low, % | 21.5 | 24.4 | 25.6 | 29.9 | 28.5 | <0.001 |

| Medium, % | 45.0 | 49.5 | 49.8 | 48.1 | 53.7 | |

| High, % | 33.4 | 26.1 | 24.6 | 21.9 | 17.8 | |

| Country of birth < | ||||||

| Australia, % | 69.7 | 67.9 | 68.0 | 69.4 | 69.2 | <0.001 |

| English-speaking, % | 14.2 | 13.3 | 12.2 | 10.4 | 7.2 | |

| Other, % | 16.1 | 18.8 | 19.8 | 20.2 | 23.6 | |

| Rurality | ||||||

| Major city, % | 69.8 | 70.7 | 72.9 | 73.1 | 71.5 | 0.076 |

| Inner regional, % | 21.0 | 19.7 | 16.9 | 17.2 | 20.8 | |

| Other, % | 9.2 | 9.6 | 10.2 | 9.7 | 7.7 | |

| Area-level disadvantage $ | ||||||

| First quintile *, % | 11.7 | 17.7 | 18.9 | 20.2 | 23.1 | <0.001 |

| Third quintile, % | 21.1 | 21.0 | 22.4 | 19.0 | 19.6 | |

| Fifth quintile **, % | 26.8 | 24.5 | 22.1 | 21.1 | 16.2 | |

| UPF, % Energy Intake | PDI | hPDI | uPDI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | |

| Crude | −0.23 (−0.32, −0.13) | <0.001 | −0.75 (−0.83, −0.67) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.79, 0.96) | <0.001 |

| Model 1 | −0.13 (−0.22, −0.04) | 0.006 | −0.65 (−0.73, −0.57) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.71, 0.88) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | −0.13 (−0.22, −0.04) | 0.005 | −0.65 (−0.73, −0.57) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.72, 0.89) | <0.001 |

| PDI | hPDI | uPDI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Groups | β (95% CI) | p Value | ||

| Healthy plant food groups | ||||

| Whole grains | 0.09 (−0.30, 0.47) | −0.09 (0.47, −0.30) | 0.652 | |

| Fruits | −1.56 (−1.93, −1.21) | 1.56 (1.21, 1.93) | <0.001 | |

| Vegetables | −2.32 (−2.70, −1.94) | 2.32 (1.94, 2.70) | <0.001 | |

| Nuts and seeds | −1.55 (−1.86, −1.24) | 1.55 (1.24, 1.86) | <0.001 | |

| Legumes | −0.09 (−0.39, 0.21) | 0.09 (−0.21, 0.39) | 0.560 | |

| Unsaturated plant oils and spreads | 1.79 (1.38, 2.19) | −1.79 (−2.19, −1.38) | <0.001 | |

| Tea and Coffee | −1.51 (−1.88, −1.14) | 1.51 (1.14, 1.88) | <0.001 | |

| Unhealthy plant food groups | ||||

| Refined grains | 1.58 (1.17, 1.99) | −1.58 (−1.99, −1.17) | 1.58 (1.17, 1.99) | <0.001 |

| Fruit juices | 0.24 (−0.06, 0.54) | −0.24 (−0.54, 0.06) | 0.24 (−0.06, 0.54) | 0.110 |

| Saturated plant fats | −1.58 (−1.93, −1.23) | 1.58 (1.23, 1.93) | −1.58 (−1.93, −1.23) | <0.001 |

| Sugars and syrups | 6.23 (5.84, 6.63) | −6.23 (−6.63, −5.84) | 6.23 (5.84, 6.63) | <0.001 |

| Misc. plant products | −0.62 (−0.92, −0.31) | 0.62 (0.31, 0.92) | −0.62 (−0.92, −0.31) | <0.001 |

| Animal food groups combined | 0.39 (0.25, 0.53) | <0.001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tolstova, N.; Machado, P.; Marchese, L.E.; Livingstone, K.M. Higher Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods Is Associated with Lower Plant-Based Diet Quality in Australian Adults. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071244

Tolstova N, Machado P, Marchese LE, Livingstone KM. Higher Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods Is Associated with Lower Plant-Based Diet Quality in Australian Adults. Nutrients. 2025; 17(7):1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071244

Chicago/Turabian StyleTolstova, Natalia, Priscila Machado, Laura E. Marchese, and Katherine M. Livingstone. 2025. "Higher Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods Is Associated with Lower Plant-Based Diet Quality in Australian Adults" Nutrients 17, no. 7: 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071244

APA StyleTolstova, N., Machado, P., Marchese, L. E., & Livingstone, K. M. (2025). Higher Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods Is Associated with Lower Plant-Based Diet Quality in Australian Adults. Nutrients, 17(7), 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071244