Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Among Families from Four Countries in the Mediterranean Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

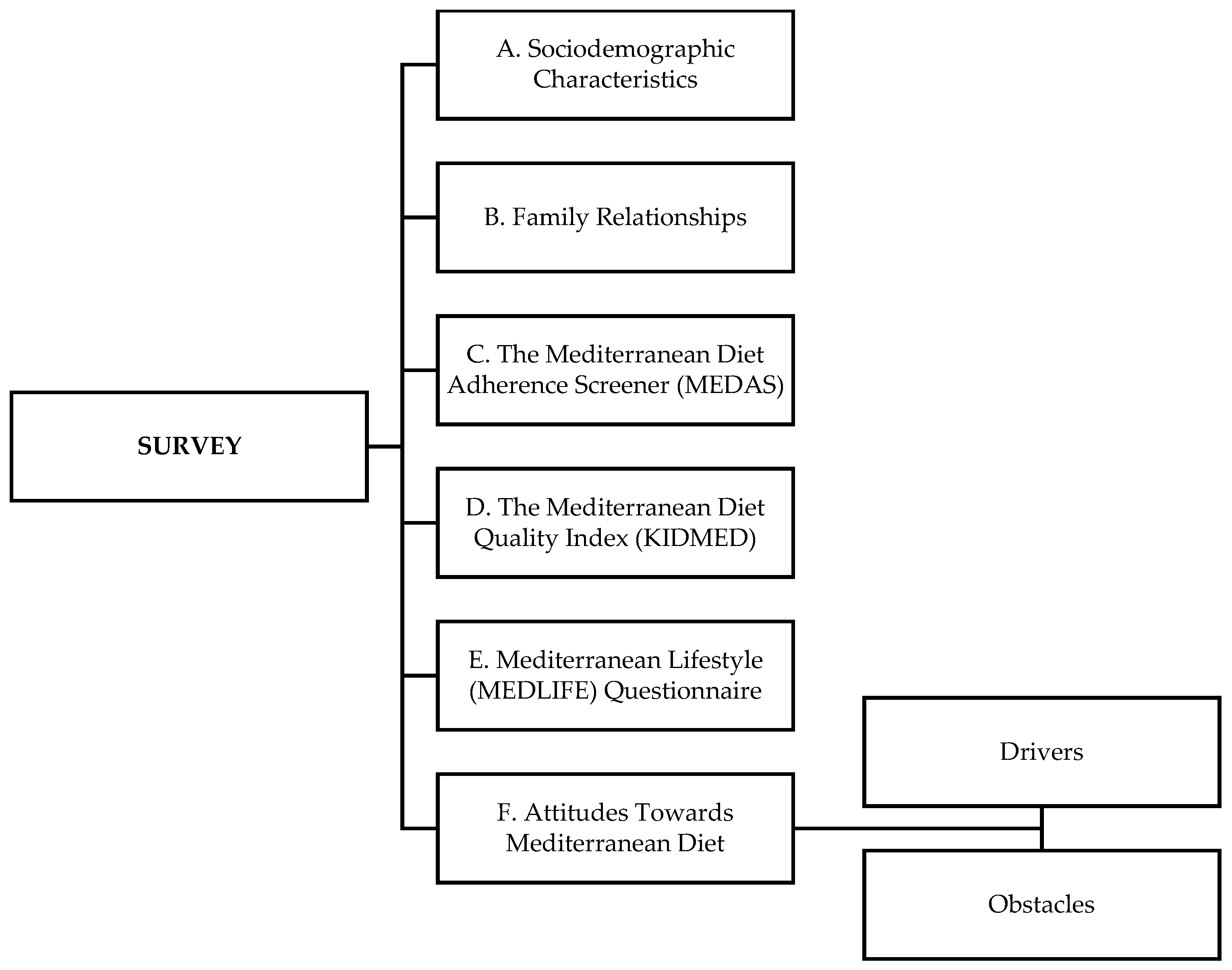

2.3. Survey Structure

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Data

2.3.2. Family Relationships

2.3.3. Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS)

2.3.4. Mediterranean Lifestyle (MEDLIFE) Index

2.3.5. Mediterranean Diet Quality Index (KIDMED)

2.3.6. Obstacles and Drivers to Mediterranean Diet Adherence

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Subjects’ Characteristics

3.2. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and Lifestyle

3.3. Family Relationships

3.4. Obstacles to and Drivers of Adherence to Mediterranean Diet

4. Discussion

4.1. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and Lifestyle

4.2. Family Relationships

4.3. Obstacles to and Drivers of Adherence to Mediterranean Diet

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| KIDMED | Mediterranean diet quality index |

| MEDAS | Mediterranean diet adherence screener |

| MedDiet | Mediterranean diet |

| MEDLIFE | Mediterranean lifestyle index |

| PREDIMED | Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

References

- Bach-Faig, A.; Berry, E.M.; Lairon, D.; Reguant, J.; Trichopoulou, A.; Dernini, S.; Medina, F.X.; Battino, M.; Belahsen, R.; Miranda, G. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2274–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. The Mediterranean diet Intangible Heritage—UNESCO. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/document-1680-Eng-2 (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Leone, A.; Battezzati, A.; De Amicis, R.; De Carlo, G.; Bertoli, S. Trends of adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern in Northern Italy from 2010 to 2016. Nutrients 2017, 9, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Willett, W. The Mediterranean diet and health: A comprehensive overview. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresán, U.; Martínez-Gonzalez, M.-A.; Sabaté, J.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. The Mediterranean diet, an environmentally friendly option: Evidence from the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarta, S.; Massaro, M.; Chervenkov, M.; Ivanova, T.; Dimitrova, D.; Jorge, R.; Andrade, V.; Philippou, E.; Zisimou, C.; Maksimova, V. Persistent moderate-to-weak Mediterranean diet adherence and low scoring for plant-based foods across several southern European countries: Are we overlooking the Mediterranean diet recommendations? Nutrients 2021, 13, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi, A.; Scazzina, F.; Giampieri, F.; Álvarez-Córdova, L.; Abdelkarim, O.; Ammar, A.; Aly, M.; Frias-Toral, E.; Pons, J.; Vázquez-Araújo, L. Lifestyle Factors Associated with Children’s and Adolescents’ Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Living in Mediterranean Countries: The DELICIOUS Project. Nutrients 2024, 17, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassıbaş, E.; Bölükbaşı, H. Evaluation of adherence to the Mediterranean diet with sustainable nutrition knowledge and environmentally responsible food choices. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1158155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, H.; Cebioglu, I.K. The relationship between Mediterranean diet adherence and mindful eating among individuals with high education level. Acıbadem Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilim. Derg. 2021, 12, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Ramos, E.; Tomaino, L.; Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Ribas-Barba, L.; Gómez, S.F.; Wärnberg, J.; Osés, M.; González-Gross, M.; Gusi, N.; Aznar, S. Trends in adherence to the Mediterranean diet in Spanish children and adolescents across two decades. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Notarnicola, M.; Cisternino, A.M.; Inguaggiato, R.; Guerra, V.; Reddavide, R.; Donghia, R.; Rotolo, O.; Zinzi, I.; Leandro, G. Trends in adherence to the Mediterranean diet in South Italy: A cross sectional study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, J.S.; Julien, S.G. Factors associated with adherence to the Mediterranean diet and dietary habits among university students in Lebanon. J. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 1, 6688462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattavelli, E.; Olmastroni, E.; Bonofiglio, D.; Catapano, A.L.; Baragetti, A.; Magni, P. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet: Impact of geographical location of the observations. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global impacts of western diet and its effects on metabolism and health: A narrative review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, N.; Villani, A.; Mantzioris, E.; Swanepoel, L. Understanding the self-perceived barriers and enablers toward adopting a Mediterranean diet in Australia: An application of the theory of planned behaviour framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggi, C.; Biasini, B.; Ogrinc, N.; Strojnik, L.; Endrizzi, I.; Menghi, L.; Khémiri, I.; Mankai, A.; Slama, F.B.; Jamoussi, H. Drivers and Barriers Influencing Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet: A Comparative Study across Five Countries. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Body Mass Index (BMI). Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/a-healthy-lifestyle---who-recommendations (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Martínez-González, M.Á.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Ros, E.; Covas, M.I.; Fiol, M.; Wärnberg, J.; Arós, F.; Ruíz-Gutiérrez, V.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Cohort profile: Design and methods of the PREDIMED study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Muñoz, L.M.; Guallar-Castillón, P.; Graciani, A.; López-García, E.; Mesas, A.E.; Aguilera, M.T.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Pattern Has Declined in Spanish Adults. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1843–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotos-Prieto, M.; Moreno-Franco, B.; Ordovás, J.M.; León, M.; Casasnovas, J.A.; Peñalvo, J.L. Design and development of an instrument to measure overall lifestyle habits for epidemiological research: The Mediterranean Lifestyle (MEDLIFE) index. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Ribas, L.; Ngo, J.; Ortega, R.M.; García, A.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta, J. Food, youth and the Mediterranean diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsofliou, F.; Vlachos, D.; Appleton, K. Barriers and facilitators to adoption of and adherence to a Mediterranean style diet in adults: A systematic review of observational and qualitative studies. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 80, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.J.; Jackson, O.; Rahman, I.; Burnett, D.O.; Frugé, A.D.; Greene, M.W. The Mediterranean diet in the stroke belt: A cross-sectional study on adherence and perceived knowledge, barriers, and benefits. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, C.A.; Gubbels, J.S.; Jaalouk, D.; Kremers, S.P.; Oenema, A. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet among adults in Mediterranean countries: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 3327–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparello, G.; Galluccio, A.; Giordano, C.; Lofaro, D.; Barone, I.; Morelli, C.; Sisci, D.; Catalano, S.; Ando, S.; Bonofiglio, D. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet pattern among university staff: A cross-sectional web-based epidemiological study in Southern Italy. Int. J. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2020, 71, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasini, B.; Rosi, A.; Menozzi, D.; Scazzina, F. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet in association with self-perception of diet sustainability, anthropometric and sociodemographic factors: A cross-sectional study in Italian adults. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazpe, I.; Santiago, S.; Toledo, E.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; de la Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Martínez-González, M.Á. Diet quality indices in the SUN cohort: Observed changes and predictors of changes in scores over a 10-year period. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 1948–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, J.; Bibiloni, M.d.M.; Serhan, M.; Tur, J.A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet among Lebanese university students. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, J.; Ghach, W.; Bouteen, C.; Makary, M.-J.; Riman, M.; Serhan, M. Adherence to Mediterranean diet among adults during the COVID-19 outbreak and the economic crisis in Lebanon. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 52, 1018–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtoğlu, S.; Uzundumlu, A.S.; Gövez, E. Olive Oil Production Forecasts for a Macro Perspective during 2024–2027. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2024, 66, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez Sanchez, M.; Gomez Sanchez, L.; Patino-Alonso, M.C.; Alonso-Domínguez, R.; Sánchez-Aguadero, N.; Lugones-Sánchez, C.; Rodriguez Sanchez, E.; Garcia Ortiz, L.; Gomez-Marcos, M.A. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet in Spanish population and its relationship with early vascular aging according to sex and age: EVA study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karam, J.; Serhan, C.; Swaidan, E.; Serhan, M. Comparative study regarding the adherence to the Mediterranean Diet among older adults living in Lebanon and Syria. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 893963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malakieh, R.; El Khoury, V.; Boumosleh, J.M.; Obeid, C.; Jaalouk, D. Individual determinants of Mediterranean diet adherence among urban Lebanese adult residents. Nutr. Food Sci. 2023, 53, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, M.; Radwan, H.; Ismail, L.C.; Faris, M.E.; Mohamad, M.N.; Saleh, S.T.; Sweid, B.; Naser, R.; Hijaz, R.; Altaher, R. Determinants for Mediterranean diet adherence beyond the boundaries: A cross-sectional study from Sharjah, the United Arab Emirates. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utri-Khodadady, Z.; Głąbska, D. Analysis of fish-consumption benefits and safety knowledge in a population-based sample of polish adolescents. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Cinelli, G.; Leggeri, C.; Caparello, G.; Barrea, L.; Scerbo, F. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam-Yellowe, T.Y. Nutritional Barriers to the Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Non-Mediterranean Populations. Foods 2024, 13, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi, A.; Scazzina, F.; Giampieri, F.; Abdelkarim, O.; Aly, M.; Pons, J.; Vázquez-Araújo, L.; Frias-Toral, E.; Cano, S.S.; Elío, I. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet in 5 Mediterranean countries: A descriptive analysis of the DELICIOUS project. Med. J. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 17, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idelson, P.I.; Scalfi, L.; Valerio, G. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, S.; Carayanni, V.; Notara, V.; Chaniotis, D. Anthropometric, lifestyle characteristics, adherence to the mediterranean diet, and COVID-19 have a high impact on the Greek adolescents’ health-related quality of life. Foods 2022, 11, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depboylu, G.Y.; Kaner, G. Younger age, higher father education level, and healthy lifestyle behaviors are associated with higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet in school-aged children. Nutrition 2023, 114, 112166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esin, K.; Ballı-Akgöl, B.; Sözlü, S.; Kocaadam-Bozkurt, B. Association between dental caries and adherence to the Mediterranean diet, dietary intake, and body mass index in children. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acito, M.; Valentino, R.; Rondini, T.; Fatigoni, C.; Moretti, M.; Villarini, M. Mediterranean Diet Adherence in Italian Children: How much do Demographic Factors and Socio-Economic Status Matter? Matern. Child Health J. 2024, 28, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masini, A.; Sanmarchi, F.; Kawalec, A.; Esposito, F.; Scrimaglia, S.; Tessari, A.; Scheier, L.M.; Sacchetti, R.; Dallolio, L. Mediterranean diet, physical activity, and family characteristics associated with cognitive performance in Italian primary school children: Analysis of the I-MOVE project. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-López, E.; Mesas, A.E.; Visier-Alfonso, M.E.; Pascual-Morena, C.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Herrera-Gutiérrez, E.; López-Gil, J.F. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms in Spanish adolescents: Results from the EHDLA study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 2637–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitri, R.N.; Boulos, C.; Ziade, F. Mediterranean diet adherence amongst adolescents in North Lebanon: The role of skipping meals, meals with the family, physical activity and physical well-being. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Torre-Moral, A.; Fàbregues, S.; Bach-Faig, A.; Fornieles-Deu, A.; Medina, F.X.; Aguilar-Martínez, A.; Sánchez-Carracedo, D. Family meals, conviviality, and the Mediterranean diet among families with adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, L.; González-Gil, E.M.; Schwarz, P.; Herrmann, S.; Karaglani, E.; Cardon, G.; De Vylder, F.; Willems, R.; Makrilakis, K.; Liatis, S. Frequency of family meals and food consumption in families at high risk of type 2 diabetes: The Feel4Diabetes-study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 2523–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, G.; Golley, R.K.; Patterson, K.A.; Coveney, J. Barriers and enablers to the family meal across time; a grounded theory study comparing South Australian parents’ perspectives. Appetite 2023, 191, 107091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalá, A.; López-Guimera, G.; Fauquet, J.; Puntí, J.; Leiva, D.; Sánchez-Carracedo, D. Association between Family Meals and the Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Spanish Adolescents. J. Child Adolesc. Behav. 2017, 5, 272–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horning, M.L.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Friend, S.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Associations among nine family dinner frequency measures and child weight, dietary, and psychosocial outcomes. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, G.; Golley, R.K.; Patterson, K.A.; Coveney, J. The Family Meal Framework: A grounded theory study conceptualising the work that underpins the family meal. Appetite 2022, 175, 106071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, S.M.; McCullough, M.B.; Rex, S.; Munafò, M.R.; Taylor, G. Family meal frequency, diet, and family functioning: A systematic review with meta-analyses. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillesund, E.R.; Sagedal, L.R.; Bere, E.; Øverby, N.C. Family meal participation is associated with dietary intake among 12-month-olds in Southern Norway. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallacker, M.; Hertwig, R.; Mata, J. The frequency of family meals and nutritional health in children: A meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 638–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, A.; Terhorst, L.; Skidmore, E.; Bendixen, R. Is frequency of family meals associated with fruit and vegetable intake among preschoolers? A logistic regression analysis. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suggs, L.S.; Della Bella, S.; Rangelov, N.; Marques-Vidal, P. Is it better at home with my family? The effects of people and place on children’s eating behavior. Appetite 2018, 121, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccaldo, R.; Censi, L.; D’Addezio, L.; Toti, E.; Martone, D.; D’Addesa, D.; Cernigliaro, A.; Group, Z.S.; Censi, L.; D’Addesa, D. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet in Italian school children (The ZOOM8 Study). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 65, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofholz, A.C.; Tate, A.D.; Miner, M.H.; Berge, J.M. Associations between TV viewing at family meals and the emotional atmosphere of the meal, meal healthfulness, child dietary intake, and child weight status. Appetite 2017, 108, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.L.; Carpentier, F.R.D.; Corvalán, C.; Popkin, B.M.; Evenson, K.R.; Adair, L.; Taillie, L.S. Television viewing and using screens while eating: Associations with dietary intake in children and adolescents. Appetite 2022, 168, 105670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, A.; Anderson, C.; McCullough, F. Associations between children’s diet quality and watching television during meal or snack consumption: A systematic review. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, 12428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Hamid, N.; Shepherd, D.; Kantono, K. How is satiety affected when consuming food while working on a computer? Nutrients 2019, 11, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Calvo, N.; Usechi, A.; Fabios, E.; Gómez, S.F.; López-Gil, J.F. Television watching during meals is associated with higher ultra-processed food consumption and higher free sugar intake in childhood. Pediatr. Obes. 2024, 19, e13130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haigh, L.; Bremner, S.; Houghton, D.; Henderson, E.; Avery, L.; Hardy, T.; Hallsworth, K.; McPherson, S.; Anstee, Q.M. Barriers and facilitators to Mediterranean diet adoption by patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Northern Europe. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihlstrom, L.; Long, A.; Himmelgreen, D. Barriers and facilitators to the consumption of fresh produce among food pantry clients. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2019, 14, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.N.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Sanchez-Villegas, A.; Alonso, A.; Pimenta, A.M.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Costs of Mediterranean and western dietary patterns in a Spanish cohort and their relationship with prospective weight change. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S.E.; McEvoy, C.T.; Prior, L.; Lawton, J.; Patterson, C.C.; Kee, F.; Cupples, M.; Young, I.S.; Appleton, K.; McKinley, M.C. Barriers to adopting a Mediterranean diet in Northern European adults at high risk of developing cardiovascular disease. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubas-Basterrechea, G.; Elío, I.; Alonso, G.; Otero, L.; Gutiérrez-Bardeci, L.; Puente, J.; Muñoz-Cacho, P. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is inversely associated with the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in older people from the north of Spain. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Türkiye (n = 201) | Italy (n = 202) | Lebanon (n = 209) | Spain (n = 200) | Total (n = 812) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of adults (years), mean ± SD | 39.1 ± 8.6 a | 42.1 ± 10.4 b | 42.9 ± 13.2 b | 46.1 ± 7.1 c | 41 ± 11.1 | <0.001 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||

| Female | 157 (78.1) a | 166 (82.2) a | 104 (49.8) b | 108 (54.0) b | 535 (65.9) | <0.001 |

| Male | 44 (21.9) | 36 (17.8) | 105 (50.2) | 92 (46.0) | 277 (34.1) | |

| Educational status, n (%) | ||||||

| Non-finished primary school | 2 (1.0) a | 1 (0.5) a | 17 (8.1) b | 4 (2.0)a | 24 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Primary school | 10 (5.0) a | 0 (0.0) b | 24 (11.5) a | 22 (11.0) a | 56 (6.9) | |

| Secondary school | 10 (5.0) a | 12 (5.9) a | 38 (18.2) b | 9 (4.5) a | 69 (8.5) | |

| High school | 36 (17.9) ab | 52 (25.7) b | 30 (14.4) a | 30 (15.0) a | 148 (18.2) | |

| Vocational school | 15 (7.5) a | 14 (6.9) a | 20 (9.6) a | 57 (28.5) b | 106 (13.1) | |

| University | 69 (34.3) | 70 (34.7) | 74 (35.4) | 62 (31.0) | 275 (33.9) | |

| Post-graduate | 59 (29.4) a | 53 (26.2) a | 6 (2.9) b | 16 (8.0) b | 134 (16.5) | |

| Occupation, n (%) | ||||||

| Manager | 23 (11.4) a | 24 (11.9) a | 9 (4.3) b | 12 (6.0) ab | 68 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| Academic laborer | 62 (30.8) ab | 6 (3.0) a | 26 (12.4) c | 12 (6.0) bc | 106 (13.1) | |

| Office worker | 36 (17.9) ab | 88 (43.6) c | 31 (14.8) b | 55 (27.5) a | 210 (25.9) | |

| Service worker | 44 (21.9) a | 16 (7.9) b | 85 (40.7) c | 42 (21.0) a | 187 (23.0) | |

| Agriculture and forestry worker | 1 (0.5) a | 5 (2.5) b | 9 (4.3) a | 9 (4.5) a | 24 (3.0) | |

| Blue-collar worker | 5 (2.5) a | 28 (13.9) bc | 49 (23.4) c | 15 (7.5) ab | 97 (11.9) | |

| Engine worker | 11 (5.5) a | 7 (3.5) a | 0 (0.0) b | 16 (8.0) a | 34 (4.2) | |

| Healthcare worker | 15 (7.5) a | 25 (12.4) a | 0 (0.0) b | 21 (10.5) a | 61 (7.5) | |

| Unskilled laborer | 4 (2.0) a | 3 (1.5) a | 0 (0.0) a | 18 (9.0) b | 25 (3.1) | |

| Income status, n (%) | ||||||

| Low | 17 (8.5) a | 19 (9.4) a | 144 (68.9) b | 24 (12.0) a | 204 (25.1) | <0.001 |

| Middle | 143 (71.1) a | 141 (69.8) a | 56 (26.8) b | 146 (73.0) a | 486 (59.9) | |

| High | 41 (20.4) a | 42 (20.8) a | 9 (4.3) b | 30 (15.0) a | 122 (15.0) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||||

| Single | 40 (19.9) a | 35 (17.3) a | 35 (16.7) a | 0 (0.0) b | 110 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| Separated/divorced | 16 (8.0) a | 7 (3.5) a | 5 (2.4) ab | 0 (0.0) b | 28 (3.4) | |

| Married/with partners | 145 (72.1) a | 160 (79.2) a | 169 (80.9) ab | 200 (100.0) b | 674 (83.0) | |

| Type of family, n (%) | ||||||

| Elementary family | 190 (94.5) ab | 197 (97.5) ab | 195 (93.3) b | 198 (99.0) a | 780 (96.1) | 0.011 |

| Extended family | 11 (5.5) | 5 (2.5) | 14 (6.7) | 2 (1.0) | 32 (3.9) | |

| Disease status, n (%) | ||||||

| Non declared pathology | 134 (66.7) | 141 (69.8) | 129 (61.7) | 148 (74.0) | 552 (68.0) | 0.056 |

| Declared pathology | 67 (33.3) | 61 (30.2) | 80 (38.3) | 52 (26.0) | 260 (32.0) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 24.9 ± 4.3 ab | 23.9± 4.1 a | 26.5 ± 4.5 b | 25.9 ± 4.7 b | 25.9 ± 4.8 | <0.001 |

| BMI classification, n (%) | ||||||

| Underweight | 3 (1.5) | 8 (4.0) | 1 (0.5) | 5 (2.5) | 17 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| Normal | 113 (56.2) ab | 125 (61.9) b | 88 (42.1) c | 95 (47.5) ac | 421 (51.8) | |

| Overweight | 57 (28.4) ab | 55 (27.2) b | 83 (39.7) a | 67 (33.5) ab | 262 (32.3) | |

| Obese | 28 (13.9) ab | 14 (6.9) b | 37 (17.7) a | 33 (16.5) a | 112 (13.8) | |

| Presence of food allergy, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 16 (8.0) ab | 33 (16.3) b | 15 (7.2) a | 28 (14.0) ab | 92 (11.3) | 0.006 |

| No | 185 (92.0) | 169 (83.7) | 194 (92.8) | 172 (86.0) | 720 (88.7) | |

| Sleep duration, mean ± SD | 7.0 ± 1.2 | 6.9 ± 1.0 | 6.6 ± 1.5 | 6.8 ± 1.2 | 6.9 ± 1.3 | 0.060 |

| Number of children, n (%) | ||||||

| None | 55 (27.4) | 61(30.2) | 51 (24.4) | 49 (24.5) | 216 (26.6) | <0.001 |

| One | 63 (31.3) a | 40 (19.8) b | 32 (15.3) b | 5 (2.5) c | 140 (17.2) | |

| Two | 67 (33.3) a | 79 (39.1) a | 62 (29.7) a | 106 (53.0) b | 314 (38.7) | |

| ≥Three | 16 (8.0) a | 22 (10.9) ab | 64 (30.6) c | 40 (20.0) bc | 142 (17.5) | |

| Age of children (years), mean ± SD | 13.4 ± 7.8 a | 12.5 ± 5.6 a | 14.6 ± 7.8 a | 11.2 ± 4.7 b | 12.4 ± 6.7 | <0.001 |

| For Adults | Türkiye (n = 201) | Italy (n = 202) | Lebanon (n = 209) | Spain (n = 200) | Total (n = 812) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEDAS score, mean ± SD | 7.71 ± 2.05 | 7.71 ± 2.07 | 7.82 ± 1.98 | 200 | 7.82 ± 2.19 | 0.353 |

| Level of adherence to the MedDiet, n (%) | ||||||

| Low | 56 (27.9) | 55 (27.2) | 54 (25.8) | 53 (28.0) | 218 (26.8) | 0.359 |

| Acceptable | 107 (53.2) | 108 (53.5) | 108 (51.7) | 91 (45.5) | 414 (51.0) | |

| High | 38 (18.9) | 39 (19.3) | 47 (22.5) | 56 (28) | 180 (22.2) | |

| MEDAS Items | ||||||

| Olive oil as main culinary fat, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 174 (86.6) ab | 201 (99.5) c | 163 (78.0) b | 188 (94.0) a | 726 (89.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 27 (13.4) | 1 (0.5) | 46 (22.0) | 12 (6.0) | 86 (10.6) | |

| Olive oil (≥4 tbsp/day), n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 138 (68.7) a | 110 (54.5) b | 103 (49.3) b | 110 (55.0) b | 461 (56.8) | <0.001 |

| No | 63 (31.3) | 92 (45.5) | 106 (50.7) | 90 (45.0) | 351 (43.2) | |

| Vegetables (≥2 portions/day), n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 114 (56.7) a | 113 (55.9) a | 143 (68.4) b | 112 (56.0) a | 482 (59.4) | 0.022 |

| No | 87 (43.3) | 89 (44.1) | 66 (31.6) | 88 (44.0) | 330 (40.6) | |

| Fruits (≥3 portions/day), n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 50 (24.9) a | 58 (38.7) a | 124 (59.3) b | 83 (41.5) c | 315 (38.8) | <0.001 |

| No | 151 (75.1) | 144 (71.3) | 85 (40.7) | 117 (58.5) | 497 (61.2) | |

| Red meat (<1 portion/day), n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 134 (66.7) abc | 125 (61.9) c | 157 (75.1) b | 125 (62.5) ac | 541 (66.6) | 0.016 |

| No | 67 (33.3) | 77 (38.1) | 52 (24.9) | 75 (37.5) | 271 (33.4) | |

| Butter or cream (<1 portion/day), n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 141 (70.1) a | 192 (95.0) b | 163 (78.0) a | 183 (91.5) b | 679 (83.6) | <0.001 |

| No | 60 (29.9) | 10 (5.0) | 46 (22.0) | 17 (8.5) | 133 (16.4) | |

| Carbonated or sweet drinks (<1 drink/day), n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 159 (79.1) ab | 174 (86.1) b | 129 (61.7) c | 149 (74.5) a | 611 (75.2) | <0.001 |

| No | 42 (20.9) | 28 (13.9) | 80 (38.3) | 51 (25.5) | 201 (24.8) | |

| Wine (≥7 glasses/week), n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 3 (1.5) a | 15 (7.4) b | 7 (3.3) ab | 16 (8.0) b | 41 (5.0) | 0.006 |

| No | 198 (98.5) | 187 (92.6) | 202 (96.7) | 184 (72.0) | 771 (95.0) | |

| Legumes (≥3 portions/week), n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 110 (54.7) a | 61 (30.2) b | 154 (73.7) c | 86 (43.0) a | 411 (50.6) | <0.001 |

| No | 91 (45.3) | 141 (69.8) | 55 (26.3) | 114 (57.0) | 401 (49.4) | |

| Fish and seafood (≥3 portions/week), n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 19 (9.5) a | 36 (17.8) a | 38 (18.2) a | 70 (35.0) b | 163 (20.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 182 (90.5) | 166 (82.2) | 171 (81.8) | 130 (65.0) | 649 (79.9) | |

| Commercial pastry (<2 portions/day), n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 151 (75.1) a | 95 (47.0) b | 104 (49.8) b | 129 (64.5) a | 479 (59.0) | <0.001 |

| No | 50 (24.9) | 107 (53.0) | 105 (50.2) | 71 (35.5) | 333 (41.0) | |

| Nuts (≥3 portions/week), n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 98 (48.8) a | 57 (28.2) b | 56 (26.8) b | 84 (42.0) a | 295 (36.3) | <0.001 |

| No | 103 (51.2) | 145 (71.8) | 153 (73.2) | 116 (58.0) | 517 (63.7) | |

| White meat preference, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 99 (49.3) a | 157 (77.7) b | 148 (70.8) b | 147 (73.5) b | 551 (67.9) | <0.001 |

| No | 102 (50.7) | 45 (22.3) | 61 (29.2) | 53 (26.5) | 261 (32.1) | |

| Sofrito (≥3 portions/week), n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 160 (79.6) a | 163 (80.7) a | 146 (69.9) ab | 128 (64.0) b | 597 (73.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 41 (20.4) | 39 (19.3) | 63 (30.1) | 72 (36.0) | 215 (26.5) | |

| MEDLIFE score, mean ± SD | 15.93 ± 3.39 a | 15.22 ± 3.74 a | 17.95 ± 3.40 b | 15.97 ± 3.63 a | 16.28 ± 3.68 | <0.001 |

| Medlife quartiles, n (%) | ||||||

| Quartile 1 (≤14) | 71 (35.3) a | 87 (43.1) a | 26 (12.4) b | 72 (36.0) a | 256 (31.5) | <0.001 |

| Quartile 2 (15–16) | 37 (18.4) | 41 (20.3) | 37 (17.7) | 41 (20.5) | 156 (19.2) | |

| Quartile 3 (17–19) | 63 (31.3) ab | 48 (23.8) b | 75 (35.9) a | 52 (26.0) ab | 238 (29.3) | |

| Quartile 4 (≥20) | 30 (14.9) a | 26 (12.9) a | 71 (34.0) b | 35 (17.5) a | 162 (20.0) | |

| For Children/Adolescents | Türkiye (n = 124) | Italy (n = 101) | Lebanon (n = 124) | Spain (n = 151) | Total (n = 500) | p |

| KIDMED score, mean ± SD | 6.29 ± 2.23 | 5.93 ± 2.44 | 5.93 ± 2.36 | 6.46 ± 2.47 | 6.18 ± 2.38 | 0.119 |

| KIDMED groups, n (%) | ||||||

| Poor (≤3) | 12 (9.7) | 16 (15.8) | 13 (10.5) | 16 (10.5) | 57 (11.4) | 0.535 |

| Average (4–7) | 73 (58.8) | 61 (60.4) | 79 (63.7) | 86 (57.0) | 299 (59.8) | |

| High (≥8) | 39 (31.4) | 24 (23.8) | 32 (25.8) | 49 (32.5) | 144 (28.8) | |

| Türkiye (n = 201) | Italy (n = 202) | Lebanon (n = 209) | Spain (n = 200) | Total (n = 812) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRIVERS | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Health | 4.33 ± 0.82 a | 4.30 ± 0.80 a | 3.93 ± 0.84 b | 4.05 ± 0.93 b | 4.15 ± 0.87 | <0.001 |

| Diet quality | 4.49 ± 0.61 a | 4.46 ± 0.64 a | 4.12 ± 0.77 b | 4.16 ± 0.78 b | 4.31 ± 0.72 | <0.001 |

| Applicability | 4.01 ± 1.08 ab | 4.28 ± 0.87 a | 3.89 ± 0.99 b | 3.99 ± 1.01 b | 4.04 ± 1.00 | <0.001 |

| Lifestyle | 4.06 ± 0.77 ab | 4.12 ± 0.80 a | 3.90 ± 0.79 b | 3.98 ± 0.80 ab | 4.01 ± 0.79 | 0.020 |

| Affordability | 3.57 ± 1.13 | 3.41 ± 1.03 | 3.52 ± 0.96 | 3.33 ± 0.97 | 3.46 ± 1.02 | 0.094 |

| Environmental factors | 3.98 ± 0.77 a | 3.84 ± 0.84 ab | 3.66 ± 0.98 b | 3.61 ± 0.91 b | 3.77 ± 0.89 | <0.001 |

| OBSTACLES | ||||||

| Health | 2.18 ± 0.78 | 2.29 ± 0.78 | 2.27 ± 0.79 | 2.21 ± 0.87 | 2.24 ± 0.80 | 0.460 |

| Lifestyle | 2.28 ± 1.37 | 2.08 ± 1.19 | 2.10 ± 1.16 | 2.12 ± 1.12 | 2.15 ± 1.22 | 0.681 |

| Affordability | 2.47 ± 1.11 a | 2.29 ± 0.96 a | 2.72 ± 0.79 b | 2.62 ± 0.96 ab | 2.53 ± 0.97 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yesildemir, O.; Guldas, M.; Boqué, N.; Calderón-Pérez, L.; Degli Innocenti, P.; Scazzina, F.; Nehme, N.; Abou Abbass, F.; de la Feld, M.; Salvio, G.; et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Among Families from Four Countries in the Mediterranean Basin. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071157

Yesildemir O, Guldas M, Boqué N, Calderón-Pérez L, Degli Innocenti P, Scazzina F, Nehme N, Abou Abbass F, de la Feld M, Salvio G, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Among Families from Four Countries in the Mediterranean Basin. Nutrients. 2025; 17(7):1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071157

Chicago/Turabian StyleYesildemir, Ozge, Metin Guldas, Noemi Boqué, Lorena Calderón-Pérez, Perla Degli Innocenti, Francesca Scazzina, Nada Nehme, Fatima Abou Abbass, Marco de la Feld, Giuseppe Salvio, and et al. 2025. "Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Among Families from Four Countries in the Mediterranean Basin" Nutrients 17, no. 7: 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071157

APA StyleYesildemir, O., Guldas, M., Boqué, N., Calderón-Pérez, L., Degli Innocenti, P., Scazzina, F., Nehme, N., Abou Abbass, F., de la Feld, M., Salvio, G., Ozyazicioglu, N., Yildiz, E., & Gurbuz, O. (2025). Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Among Families from Four Countries in the Mediterranean Basin. Nutrients, 17(7), 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071157