Conditions for Nutritional Care of Elderly Individuals with Dementia and Their Caregivers: An Exploratory Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

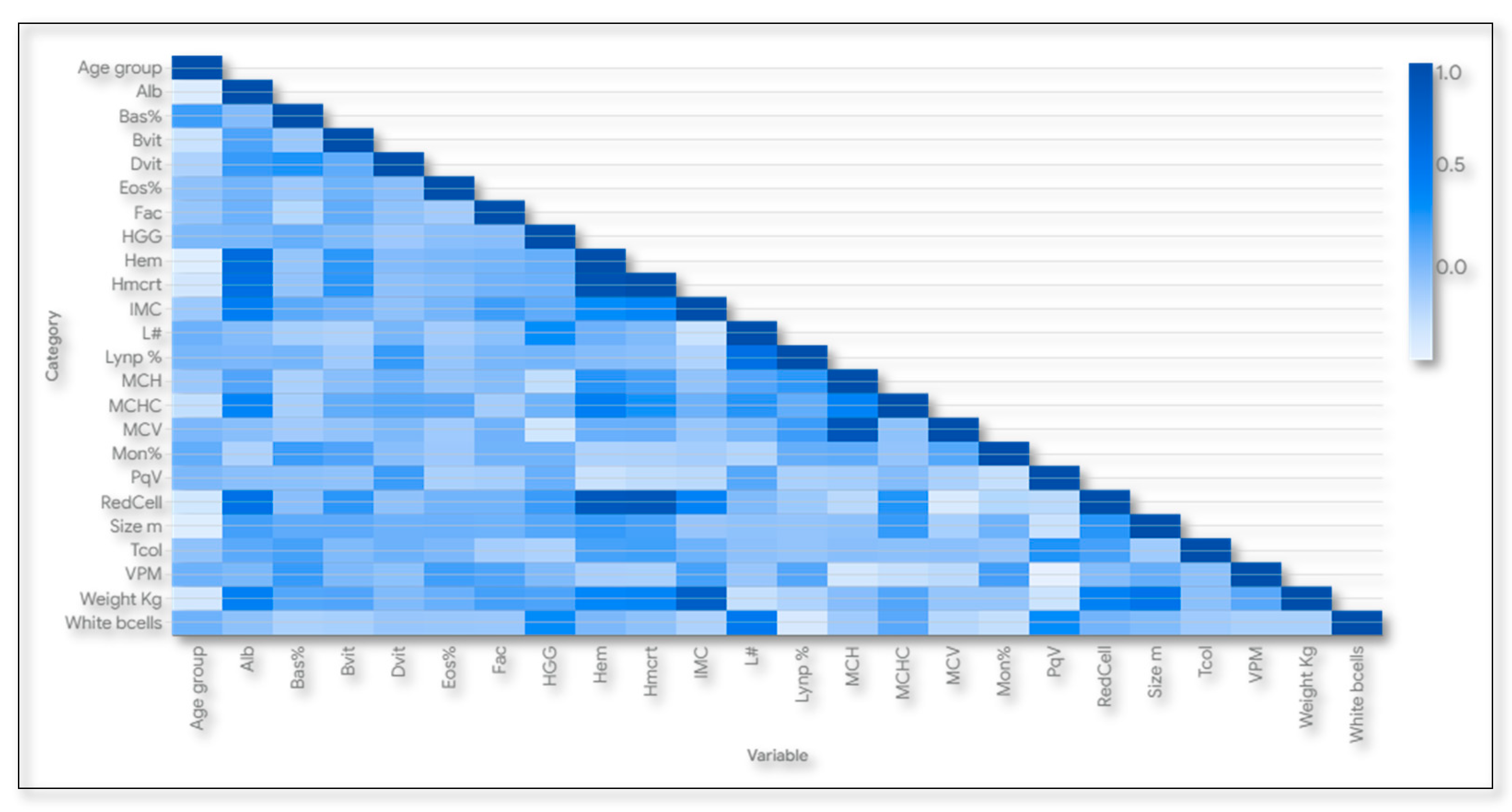

2.3. Statistic Analysis and Methodological Rigor

2.4. Ethical and Environmental Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Ageing 2019 (ST/ESA/SER.A/444); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Dementia; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Yassine, H.N.; Samieri, C.; Livingston, G.; Glass, K.; Wagner, M.; Tangney, C.; Plassman, B.L.; Ikram, M.A.; Gu, Y.; O’Bryant, S. Nutrition state of science and dementia prevention: Recommendations of the Nutrition for Dementia Prevention Working Group. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022, 3, e501–e512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, M.; Guerchet, M.; Albanese, E.; Prina, M. Nutrition and Dementia: A Review of Available Research; Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI): London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Penacho Lázaro, M.D.; Calleja Fernández, A.; Castro Penacho, S.; Tierra Rodríguez, A.M.; Vidal Casariego, A. Valoración del riesgo de malnutrición en pacientes institucionalizados en función del grado de dependencia. Nutr. Hosp. 2019, 36, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, A.; Sugimoto, T.; Kitamori, K.; Saji, N.; Niida, S.; Toba, K.; Sakurai, T. Malnutrition is associated with behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia in older women with mild cognitive impairment and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borda, M.G.; Ayala Copete, A.M.; Tovar-Rios, D.A.; Jaramillo-Jimenez, A.; Giil, L.M.; Soennesyn, H.; Gómez-Arteaga, C.; Venegas-Sanabria, L.C.; Kristiansen, I.; Chavarro-Carvajal, D.A.; et al. Association of malnutrition with functional and cognitive trajectories in people living with dementia: A five-year follow-up study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 79, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciliz, O.; Tulek, Z.; Hanagasi, H.; Bilgic, B.; Gurvit, I.H. Eating Difficulties and Relationship with Nutritional Status Among Patients with Dementia. J. Nurs. Res. 2023, 31, e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gómez, M.E.; Zapico, S.C. Frailty, cognitive decline, neurodegenerative diseases and nutrition interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, V.E.; Herrera, P.F.; Laura, R. Effect of nutrition on neurodegenerative diseases. A systematic review. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 810–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente de Sousa, O.; Mendes, J.; Amaral, T.F. Association between nutritional and functional status indicators with caregivers’ burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 79, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labyak, C.; Sealey-Potts, C.; Wright, L.; Kriek, C.; Dilts, S. Informal caregiver and healthcare professional perspectives on dementia and nutrition. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 37, 1308–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantón Blanco, A.; Lozano Fuster, F.M.; Olmo García, M.; Virgili Casas, N.; Wanden-Berghe, C.; Avilés, V.; Ashbaugh Enguídanos, R.; Ferrero López, I.; Molina Soria, J.B.; Montejo González, J.C.; et al. Manejo nutricional de la demencia avanzada: Resumen de recomendaciones del Grupo de Trabajo de Ética de la SENPE. Nutr. Hosp. 2019, 36, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Fergusson, M.E.; Caez-Ramírez, G.R.; Sotelo-Díaz, L.I.; Sánchez-Herrera, B. Nutritional Care for Institutionalized Persons with Dementia: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urrunaga-Pastor, D.; Chambergo-Michilot, D.; Runzer-Colmenares, F.M.; Pacheco-Mendoza, J.; Benites-Zapata, V.A. Prevalence of cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults living at high altitude: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2021, 50, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparro-Díaz, L.; Sánchez-Herrera, B.; González, G.M. Encuesta de caracterización del cuidado de la diada cuidadorfamiliar-persona con enfermedad crónica. Rev. Cienc. Y Cuid. 2014, 11, 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Melengüe Diaz, B. Relación Entre Soporte Social y TIC´s en Cuidadores Familiares de Personas con Esclerosis Lateral Amiotrófica. [Tesis de investigación]. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia, 2015. Available online: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/bitstream/handle/unal/55704/1024486474.2015.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Fostinelli, S.; De Amicis, R.; Leone, A.; Giustizieri, V.; Binetti, G.; Bertoli, S.; Battezzati, A.; Cappa, S.F. Eating behavior in aging and dementia: The need for a comprehensive assessment. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 604488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanden-Berghe, C. Evaluación nutricional en mayores. Hosp. A Domic. 2022, 6, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinis, I.; Vrca, A.; Bevanda, M.; Botić-Štefanec, S.; Bađak, J.; Kušter, D.; Suttil, T.; Lasić, M.; Bolarić, K.; Bituh, M. Nutritional assessment of patients with primary progressive dementia at the time of diagnosis. Psychiatr. Danub. 2021, 33 (Suppl. 13), 226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud de Colombia, Subdirección de Enfermedades No Transmisibles. Valoración Nutricional de la Persona Adulta Mayor. Bogotá: Ministerio de Salud de Colombia. 2021. Available online: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/PP/ENT/valoracion-nutricional-persona-adulta-mayor.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Paulose-Ram, R.; Graber, J.E.; Woodwell, D.; Ahluwalia, N. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2021–2022: Adapting data collection in a COVID-19 environment. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 2149–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MSD. MSD Manuals: Professional Version. [Internet]. Kenilworth, NJ: Merck & Co., Inc. 2021. Available online: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Saucedo-Figueredo, M.C.; Morilla-Herrera, J.C.; Gálvez-González, M.; Rivas-Ruiz, F.; Nava-DelVal, A.; San Alberto-Giraldos, M.; Hierrezuelo-Martín, M.J.; Gómez-Borrego, A.B.; Kaknani-Uttumchandani, S.; Morales-Asencio, J.M. Anchor-Based and Distributional Responsiveness of the Spanish Version of the Edinburgh Feeding Evaluation in Dementia Scale in Older People with Dementia: A Longitudinal Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo Figueredo, M.C.; Morilla Herrera, J.C.; San Alberto Giraldos, M.; López Leiva, I.; León Campos, Á.; Martí García, C.; García Mayor, S.; Kaknani Uttumchandani, S.; Morales Asencio, J.M. Validation of the Spanish version of the Edinburgh Feeding Evaluation in Dementia Scale for older people with dementia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, M.F.; Martin-Cook, K.; Svetlik, D.A.; Saine, K.; Foster, B.; Fontaine, C.S. The quality of life in late-stage dementia (QUALID) scale. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2000, 1, 114–116. [Google Scholar]

- Garre-Olmo, J.; Planas-Pujol, X.; López-Pousa, S.; Weiner, M.F.; Turon-Estrada, A.; Juvinyà, D.; Ballester, D.; Vilalta-Franch, J. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of a Spanish version of the Quality of Life in Late-Stage Dementia Scale. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo González, G.M.; Sánchez Herrara, B.; Elizabeth, V.R. Desarrollo y pruebas psicométricas del Instrumento" cuidar"-versión corta para medir la competencia de cuidado en el hogar. Rev. De La Univ. Ind. De Santander Salud 2016, 48, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P.; Bethencourt, J.M.; Ibáñez, I.; Fortes, D. Gender and psychological well-being in older adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makowski, D.; Ben-Shachar, M.S.; Patil, I.; Lüdecke, D. Methods and algorithms for correlation analysis in R. J. Open Source Softw. 2020, 5, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierer, B.E. Declaration of Helsinki—Revisions for the 21st Century. JAMA 2025, 333, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopera, M.M. Revisión comentada de la legislación colombiana en ética de la investigación en salud. Biomédica 2017, 37, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congreso de la República de Colombia. Ley 2169 de 2021; Congreso de la República de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021. Available online: https://www.suin-juriscol.gov.co/viewDocument.asp?id=30043747 (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Nichols, E.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdoli, A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Akram, T.T.; et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, A.; Shang, Y.; Xu, W.; Grande, G.; Laukka, E.J.; Fratiglioni, L.; Marseglia, A. The impact of diabetes on cognitive impairment and its progression to dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, K.B.; Askew, C.D.; Greaves, K.; Summers, M.J. The effect of non-stroke cardiovascular disease states on risk for cognitive decline and dementia: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2018, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohria, A.; Tsang, S.W.; Fang, J.C.; Lewis, E.F.; Jarcho, J.A.; Mudge, G.H.; Stevenson, L.W. Clinical assessment identifies hemodynamic profiles that predict outcomes in patients admitted with heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 1797–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sosa, S.; Santana-Vega, P.; Rodríguez-Quintana, A.; Rodríguez-González, J.A.; García-Vallejo, J.M.; Puente-Fernández, A.; Conde-Martel, A. Nutritional Status of Very Elderly Outpatients with Heart Failure and Its Influence on Prognosis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Lonati, C.; Tescaro, L.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Proietti, M.; Lombardo, M.; Harari, S. Prevalence and clinical outcome of main echocardiographic and hemodynamic heart failure phenotypes in a population of hospitalized patients 70 years old and older. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 1081–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-García, Y.; Díaz-Camellón, D.J.; de Armas-Mestre, J.; Soria-Pérez, R.; Merencio-Leyva, N. Caracterización de cuidadores de adultos mayores con demencia. Cárdenas, 2019. Rev. Méd. Electrón. 2022, 44, 822–833. [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal Carrascal, G.; Fuentes Ramírez, A.; Pulido Barragán, S.P.; Guevara Lozano, M.; Sánchez-Herrera, B. Effects of the discharge plan on the caregiving load of people with chronic disease: Quasi-experimental study. Chronic Illn. 2024, 20, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Torralbo, C.M.; Cueto Torres, I.; Grande Gascón, M.L. Diferencias de carga en el cuidado asociadas al género. Ene 2020, 14, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukadam, N.; Sommerlad, A.; Huntley, J.; Livingston, G. Population attributable fractions for risk factors for dementia in low-income and middle-income countries: An analysis using cross-sectional survey data. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e596–e603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trani, J.F.; Moodley, J.; Maw, M.T.; Babulal, G.M. Association of multidimensional poverty with dementia in adults aged 50 years or older in South Africa. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e224160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beydoun, M.A.; Beydoun, H.A.; Banerjee, S.; Weiss, J.; Evans, M.K.; Zonderman, A.B. Pathways explaining racial/ethnic and socio-economic disparities in incident all-cause dementia among older US adults across income groups. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, C.; Cetó, M.; Arias, A.; Blasco, E.; Gil, M.P.; López, R.; Dakterzada, F.; Purroy, F.; Piñol-Ripoll, G. Nivel de conocimiento de la enfermedad de Alzheimer en cuidadores y población general. Neurología 2021, 36, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leocadie, M.C.; Morvillers, J.M.; Pautex, S.; Rothan-Tondeur, M. Characteristics of the skills of caregivers of people with dementia: Observational study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, D.; Guzmán, J.A.; Vargas, N.; Ramos, J. Carga de trabajo del cuidador del adulto mayor. Cina Res. 2018, 2, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- van den Kieboom, R.; Snaphaan, L.; Mark, R.; Bongers, I. The trajectory of caregiver burden and risk factors in dementia progression: A systematic review. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 77, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Noh, G.O.; Kim, K. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and family caregiver burden: A path analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Kim, J.I.; Na, H.R.; Lee, K.S.; Chae, K.H.; Kim, S. Factors influencing caregiver burden by dementia severity based on an online database from Seoul dementia management project in Korea. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.P.; Buckley, M.M.; Cryan, J.F.; Ní Chorcoráin, A.; Dinan, T.G.; Kearney, P.M.; O’Caoimh, R.; Calnan, M.; Clarke, G.; Molloy, D.W. Informal caregiving for dementia patients: The contribution of patient characteristics and behaviours to caregiver burden. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gove, D.; Nielsen, T.R.; Smits, C.; Plejert, C.; Rauf, M.A.; Parveen, S.; Jaakson, S.; Golan-Shemesh, D.; Lahav, D.; Kaur, R.; et al. The challenges of achieving timely diagnosis and culturally appropriate care of people with dementia from minority ethnic groups in Europe. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 36, 1823–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soysal, P.; Dokuzlar, O.; Erken, N.; Günay, F.S.; Isik, A.T. The relationship between dementia subtypes and nutritional parameters in older adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1430–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llerena, L.D.; Hidalgo, P.A. Estrategias nutricionales en pacientes con Alzheimer: Una revisión de literatura. Rev. Científica De Salud BIOSANA 2024, 4, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishino, Y.; Sugimoto, T.; Kimura, A.; Kuroda, Y.; Uchida, K.; Matsumoto, N.; Saji, N.; Niida, S.; Sakurai, T. Longitudinal association between nutritional status and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in older women with mild cognitive impairment and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 1906–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro-Díaz, L.; Carreño-Moreno, S.; Arias-Rojas, M. Soledad en el adulto mayor: Implicaciones para el profesional de enfermería. Rev. Cuid. 2019, 10, e633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, G.; Werlinger, E.; Contreras, L.; González, A.; Vera, A.; Juica, S.; Fuentealba, M. Calidad de Vida en Demencia Alzheimer: Un nuevo desafío. Rev. Chil. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2021, 59, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Montaño, L.R.; Pérez-Corrales, J.; Pérez-de-Heredia-Torres, M.; Martin-Pérez, A.M.; Güeita-Rodríguez, J.; Velarde-García, J.F.; Palacios-Ceña, D. Spiritual care in advanced dementia from the perspective of health providers: A qualitative systematic review. Occup. Ther. Int. 2021, 2021, 9998480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias, C.E.; Cabrera, E.; Zabalegui, A. Informal caregivers’ roles in dementia: The impact on their quality of life. Life 2020, 10, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.; da Mata, F.A.F.; Aubeeluck, A. Quality of life of family carers of people living with dementia: Review of systematic reviews of observational and intervention studies. Br. Med. Bull. 2024, 149, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobão, M.J.; Guan, Y.; Curado, J.; Goncalves, M.; Melo, R.; Silva, C.; Velosa, T.; Cardoso, S.; Santos, V.; Santos, C. Solution to support informal caregivers of patients with dementia. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 181, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, A.; Papastavrou, E.; Middleton, N.; Markatou, A.; Sakka, P. How caregivers of people with dementia search for dementia-specific information on the internet: Survey study. JMIR Aging 2020, 3, e15480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambegaonkar, A.; Ritchie, C.; de la Fuente Garcia, S. The use of mobile applications as communication aids for people with dementia: Opportunities and limitations. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2021, 5, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damant, J.; King, D.; Karagiannidou, M.; Dangoor, M.; Freddolino, P.; Hu, B.; Wittenberg, R. Unpaid carers of people with dementia and information communication technology: Use, impact and ideas for the future. Dementia 2024, 23, 779–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, C.; Ang, T.; Au, R. BMI decline patterns and relation to dementia risk across four decades of follow-up in the Framingham Study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 2520–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Hu, H.Y.; Ou, Y.N.; Shen, X.N.; Xu, W.; Wang, Z.; Quina, D.; Yu, J.T. Association of body mass index with risk of cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 115, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yan, R.; Chen, Q.; Ying, X.; Zhai, Y.; Li, F.; Lin, J. Body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio and cognitive function among Chinese elderly: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.H.; Park, Y.; Kim, N.H.; Kim, S.G. Weight-adjusted waist index reflects fat and muscle mass in the opposite direction in older adults. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S.; Kapoor, N.; Jacob, J.J.; Agarwal, N.; Thakor, P.; Malve, H. Fluid Imbalance in Geriatrics: The Need for Optimal Hydration. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2023, 71, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nazar, G.; Díaz-Toro, F.; Roa, P.; Petermann-Rocha, F.; Troncoso-Pantoja, C.; Leiva-Ordóñez, A.M.; Cigarroa, I.; Celis-Morales, C. Asociación entre salud oral y deterioro cognitivo en personas mayores chilenas. Gac. Sanit. 2023, 37, 102303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiuchi, S.; Cooray, U.; Kusama, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Abbas, H.; Nakazawa, N.; Kondo, K.; Osaka, K.; Aida, J. Oral status and dementia onset: Mediation of nutritional and social factors. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Gang, X.; Wang, G. Grip strength and the risk of cognitive decline and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 625551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyuer, F.; Cankurtaran, F.; Menevşe, Ö.; Zararsız, G.E. Examination of the correlation between hand grip strength and muscle mass, balance, mobility, and daily life activities in elderly individuals living in nursing homes. Work 2023, 74, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.C.; Chou, C.C.; Bintoro, B.S.; Chien, K.L.; Bai, C.H. High sensitivity C-reactive protein and glycated hemoglobin levels as dominant predictors of all-cause dementia: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Immun. Ageing 2022, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Xing, Y.; Jia, J.; Tang, Y. B vitamins and prevention of cognitive decline and incident dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 931–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, S.; Taimuri, U.; Basnan, S.A.; Ai-Orabi, W.K.; Awadallah, A.; Almowald, F.; Hazazi, A. Low vitamin D and its association with cognitive impairment and dementia. J. Aging Res. 2020, 2020, 6097820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojai, S.; Haeri Rohani, S.A.; Moosavi-Movahedi, A.A.; Habibi-Rezaei, M. Human serum albumin in neurodegeneration. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 33, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, O.; Kędziora-Kornatowska, K. Cholesterol and dementia: A long and complicated relationship. Curr. Aging Sci. 2020, 13, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwagami, M.; Qizilbash, N.; Gregson, J.; Douglas, I.; Johnson, M.; Pearce, N.; Evans, S.; Pocock, S. Blood cholesterol and risk of dementia in more than 1· 8 million people over two decades: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e498–e506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Y.X.; Deng, Y.T.; Zhang, Y.R.; Wang, H.F.; Zhang, W.; Dong, Q.; Feng, J.F.; Cheng, W.; Yu, J.T. Associations of blood cell indices and anemia with risk of incident dementia: A prospective cohort study of 313,448 participants. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 3965–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, S.; Heck, J.; Groh, A.; Frieling, H.; Bleich, S.; Kahl, K.G.; Bosch, J.J.; Krichevsky, B.; Schulze-Westhoff, M. White blood cell and platelet counts are not suitable as biomarkers in the differential diagnostics of dementia. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A.; Lipari, A.; Di Francesco, S.; Ianuà, E.; Liperoti, R.; Cipriani, M.C.; Martone, A.M.; De Candia, E.; Landi, F.; Montalto, M. Platelets and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Assessed Aspect | Subject | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person with Dementia | Caregiver | ||||

| % | % | ||||

| Sociodemographic profile | Sex | Male | 37.0 | 9.6 | |

| Female | 63.0 | 90.4 | |||

| Education level | No education | 2.7 | 0 | ||

| Primary | 38.4 | 0 | |||

| Secondary (High school) | 9.6 | 1.3 | |||

| Technical or Technologist | 11.0 | 97.2 | |||

| Professional | 12.3 | 1.3 | |||

| Postgraduate | 2.7 | 0 | |||

| Non-Applicable or No Response (N.A./N.R.) | 23.3 | 0 | |||

| Housing | Origin | Andean Region | 93.2 | 83.5 | |

| Other region | 4.1 | 13.6 | |||

| Other country | 0 | 2.7 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 2.7 | 0 | |||

| Place of residence | Andean Region | 100 | 100 | ||

| Type of residence | Particular | 2.7 | 100 | ||

| Institution | 97.3 | 0 | |||

| Residential Area | Urban | 86.3 | 4 | ||

| Rural | 13.7 | 67.1 | |||

| Marital Status | Single | 34.2 | 54.7 | ||

| Married | 23.3 | 6.8 | |||

| Separated | 4.1 | 0 | |||

| Common-law | 4.1 | 38.3 | |||

| Widow(er) | 30.1 | 0 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 4.1 | 0 | |||

| Occupation (previous, in the case of older adults) | Housekeeper | 8.21 | 0 | ||

| Employee | 8.21 | 100 | |||

| Independent | 11.0 | 0 | |||

| Student | 0 | 0 | |||

| Agriculture | 19.2 | 0 | |||

| Driver | 5.5 | 0 | |||

| Others | 6.8 | 0 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 41.1 | 0 | |||

| Health Status | Cognitive Sphere | Intact | 0 | 100 | |

| Altered | 100 | 0 | |||

| Level of Functionality | Functional | 0 | 100 | ||

| Moderate dependence | 72.6 | 0 | |||

| High dependence | 27.4 | 0 | |||

| Medical Diagnoses | Healthy | 0 | 81 | ||

| With medical diagnosis | 100 | 19 | |||

| Severe cognitive impairment (CI) | 100 | 0 | |||

| CI + cardiovascular disease | 60.3 | 0 | |||

| CI + endocrine disease | 28.8 | 0 | |||

| CI + gastrointestinal disease | 5.5 | 0 | |||

| CI + respiratory disease | 4.1 | 0 | |||

| CI + musculoskeletal disease | 12.3 | 0 | |||

| CI + sensory organ disease | 4.1 | 0 | |||

| CI + neurological disease | 11.0 | 0 | |||

| CI + psychiatric disease | 13.7 | 0 | |||

| CI + renal disease | 1.4 | 0 | |||

| CI + dermatological disease | 2.7 | 0 | |||

| Socioeconomic status | Low (1–2) | 60.3 | 67.1 | ||

| Medium (3–4) | 26.0 | 33 | |||

| High (5–6) | 12.3 | 0 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 1.4 | 0 | |||

| Religion | Type | Catholic | 86.3 | 85 | |

| Christian | 5.5 | 8.2 | |||

| Agnostic | 0 | 1.4 | |||

| Atheist | 4.1 | 5.5 | |||

| Other | 0 | 0 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 4.1 | 0 | |||

| Level of commitment | High | 61.6 | 0 | ||

| Medium | 23.3 | 60.3 | |||

| Low | 11.0 | 24.7 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 4.1 | 0 | |||

| Perception of burden and support | Provides care for people with dementia | Since diagnosis | N.A. | 23.3 | |

| After diagnosis | N.A. | 76.7 | |||

| Sole caregiver | Yes | N.A. | 0 | ||

| No | N.A. | 100 | |||

| Daily hours required for care | 11 h or less | 4.1 | 19.2 | ||

| 12 to 23 h | 19.2 | 54.7 | |||

| 24 h | 75.3 | 24.7 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 1.4 | 0 | |||

| Type of caregiver | Family member | N.A. | 0 | ||

| Formal caregiver | 100 | ||||

| Time spent as a caregiver | Less than 1 year | N.A. | 20.5 | ||

| 1 to 2 years | 12.3 | ||||

| 2 to 4 years | 9.6 | ||||

| More than 4 to 10 years | 34.2 | ||||

| More than 10 years | 23.3 | ||||

| Previous caregiving experience | No experience | N.A. | 15 | ||

| With experience | 85 | ||||

| Perception of burden or support | High | 17.8 | 35.6 | ||

| Medium | 16.4 | 48 | |||

| Low | 52.1 | 16.4 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 13.7 | 0 | |||

| Psychological support | 0 | 17.8 | 45.2 | ||

| 1 | 9.6 | 1.4 | |||

| 2 | 13.7 | 13.7 | |||

| 3 | 38.4 | 24.7 | |||

| 4 | 12.3 | 15 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 8.2 | 0 | |||

| Family support | 0 | 4.1 | 11 | ||

| 1 | 1.4 | 1.4 | |||

| 2 | 24.7 | 2.7 | |||

| 3 | 24.7 | 19.1 | |||

| 4 | 24.7 | 65.7 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 8.2 | 0 | |||

| Religious support | 0 | 23.3 | 64.3 | ||

| 1 | 2.7 | 11 | |||

| 2 | 5.5 | 6.8 | |||

| 3 | 23.3 | 2.7 | |||

| 4 | 38.3 | 15 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 6.8 | 0 | |||

| Economic support | 0 | 6.8 | 49.3 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 4.1 | |||

| 2 | 0 | 8.2 | |||

| 3 | 57.5 | 22 | |||

| 4 | 27.3 | 16.4 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 8.2 | 0 | |||

| Social support | 0 | 13.6 | 19.1 | ||

| 1 | 8.2 | 6.5 | |||

| 2 | 19.1 | 15 | |||

| 3 | 35.6 | 35.6 | |||

| 4 | 15 | 23.2 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 8.2 | 0 | |||

| Perception of well-being | Physical well-being | 0 | 1.4 | 0 | |

| 1 | 6.8 | 2.7 | |||

| 2 | 23.3 | 12.3 | |||

| 3 | 41 | 48 | |||

| 4 | 16.4 | 37 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 11 | 0 | |||

| Psycho-emotional well-being | 0 | 1.4 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 11 | 0 | |||

| 2 | 20.5 | 13.6 | |||

| 3 | 46.5 | 48 | |||

| 4 | 11 | 34.3 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 9.5 | 0 | |||

| Social well-being | 0 | 1.4 | 1.4 | ||

| 1 | 15 | 6.8 | |||

| 2 | 22 | 15 | |||

| 3 | 34.2 | 35.6 | |||

| 4 | 19.1 | 41 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 8.2 | 0 | |||

| Spiritual well-being | 0 | 4.1 | 1.4 | ||

| 1 | 5.5 | 8.2 | |||

| 2 | 4.1 | 19.1 | |||

| 3 | 30 | 26 | |||

| 4 | 48 | 45.2 | |||

| N.A./N.R. | 8.2 | 0 | |||

| Level of Technology Use for Care | TV | 61.4% | 88.4% | ||

| Radio | 28.4% | 64.5% | |||

| Computer | 12.0% | 74.6% | |||

| Phone | 17.7% | 96.7% | |||

| Internet | 12.8% | 84.8% | |||

| Type of Nutritional Guidance | % | |

|---|---|---|

| No orientation | 69.9 | |

| Enriched diet | High in iron and fiber with liquefied protein | 1.40 |

| Hypoglycemic diets | Hypoglycemic | 12.5 |

| Hypoglycemic, dairy-free, no pork | ||

| Hypoglycemic, seafood allergy | ||

| Hypoglycemic, soft proteins and thick juices | ||

| Hypoglycemic, liquefied proteins | ||

| Liquefied proteins | ||

| Hypoglycemic, high in fiber, no grains | ||

| Hypoglycemic, cardiovascular alteration diet | ||

| Hypoglycemic, red meat up to 2 times/week | ||

| Low-sodium diets | Low sodium | 2.8 |

| Low sodium, no dairy, and fluid restriction | ||

| Diet for cardiovascular issues | Cardiovascular alteration diet | 5.5 |

| Cardiovascular alteration diet, no soups | ||

| Other food restrictions | Unsweetened juices | 5.2 |

| No acidic foods, no dairy | ||

| No juices, liquefied protein | ||

| No dairy, no grains | ||

| Indicator | Results in % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Deficit/Low | Normal | Excess/High | |

| BMI | 24.7 | 52.1 | 15.1 |

| Arm circumference | 61.6 | 34.2 | 2.7 |

| Calf circumference | Moderate 30.1 | 41.1 | 0.0 |

| Severe 28.8 | |||

| Hydration | 13.7 | 84.9 | 0.0 |

| Oral condition | 0.0 | 15.1 | N.A. |

| 11.0 | 30.1 | N.A. | |

| 32.9 | N.A. | N.A. | |

| Waist circumference | 0.0 | 38.4 | 58.9 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.0 | 5.5 | Moderate 24.7 |

| Severe 57.5 | |||

| Grip strength | 21.9 | 4.1 | 0.0 |

| Type of Test | Results in % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Normal | High | ||

| Glycated hemoglobin | 0 | 73.9 | Prediabetic 13 | |

| Diabetic 8.6 (controlled 2.8) | ||||

| Vitamins | Vitamin B12 | 1.01 | 85.5 | 0 |

| Vitamin D | 50.7 | 44.9 | 0 | |

| Folic acid | 0 | 94.2 | 14 | |

| Albumin | 2.8 | 78.2 | 13.0 | |

| Total cholesterol | 0 | 57.9 | Limit 21.7 | |

| High 15.9 | ||||

| Complete blood count | Hemoglobin | 24.6 | 66.6 | 4.3 |

| Hematocrit | 39.1 | 53.6 | 2.8 | |

| Red blood cell count | 39.1 | 53.6 | 2.8 | |

| Mean corpuscular volume | 2.8 | 85.5 | 7.2 | |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin | 2.8 | 44.9 | 47.8 | |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration | 0 | 50.7 | 44.9 | |

| Red cell distribution width | 0 | 71.0 | 24.6 | |

| White blood cells | 7.2 | 88.4 | 0 | |

| Neutrophils % | 1.4 | 89.5 | 4.3 | |

| Neutrophils (absolute count) | 0 | 94.2 | 1.4 | |

| Lymphocytes % | 1.4 | 91.3 | 2.8 | |

| Lymphocytes (absolute count) | 4.3 | 91.3 | 0 | |

| Monocytes % | 10.1 | 76.8 | 8.6 | |

| Monocytes (absolute count) | 27.5 | 68.1 | 0 | |

| Eosinophils % | 0 | 89.5 | 5.7 | |

| Eosinophils (absolute count) | 44.9 | 50.7 | 0 | |

| Basophils % | 0 | 94.2 | 1.4 | |

| Basophils (absolute count) | 0 | 94.2 | 0 | |

| Platelet count, automated method | 4.3 | 94.2 | 11.5 | |

| Mean platelet volume | 8.6 | 75.3 | 11.5 | |

| Problem Assessed | Performance Level % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Somewhat Committed | Very Committed | |

| 59 | 8 | 33 |

| 77 | 7 | 16 |

| 70 | 12 | 18 |

| 67 | 19 | 14 |

| 85 | 11 | 4 |

| 85 | 10 | 5 |

| 92 | 5 | 3 |

| 95 | 0 | 5 |

| 92 | 3 | 5 |

| 84 | 11 | 5 |

| Condition Assessed | Occurrence Level % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Smiling | 49.2 | 16.9 | 11.3 | 12.7 | 9.8 |

| Sadness | 45.1 | 22.5 | 12.7 | 12.7 | 7.0 |

| Crying | 63.4 | 15.5 | 11.3 | 8.4 | 1.4 |

| Discomfort | 39.4 | 36.6 | 14.1 | 1.4 | 8.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarmiento-González, P.; Moreno-Fergusson, M.E.; Sotelo-Diaz, L.I.; Caez-Ramírez, G.R.; Ramírez-Flórez, L.N.; Sánchez-Herrera, B. Conditions for Nutritional Care of Elderly Individuals with Dementia and Their Caregivers: An Exploratory Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17061007

Sarmiento-González P, Moreno-Fergusson ME, Sotelo-Diaz LI, Caez-Ramírez GR, Ramírez-Flórez LN, Sánchez-Herrera B. Conditions for Nutritional Care of Elderly Individuals with Dementia and Their Caregivers: An Exploratory Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(6):1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17061007

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarmiento-González, Paola, Maria Elisa Moreno-Fergusson, Luz Indira Sotelo-Diaz, Gabriela Rabe Caez-Ramírez, Laura Nathaly Ramírez-Flórez, and Beatriz Sánchez-Herrera. 2025. "Conditions for Nutritional Care of Elderly Individuals with Dementia and Their Caregivers: An Exploratory Study" Nutrients 17, no. 6: 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17061007

APA StyleSarmiento-González, P., Moreno-Fergusson, M. E., Sotelo-Diaz, L. I., Caez-Ramírez, G. R., Ramírez-Flórez, L. N., & Sánchez-Herrera, B. (2025). Conditions for Nutritional Care of Elderly Individuals with Dementia and Their Caregivers: An Exploratory Study. Nutrients, 17(6), 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17061007