Associations Between the Food Environment and Food Insecurity on Fruit, Vegetable, and Nutrient Intake, and Body Mass Index, Among Urban-Dwelling Latina Breast Cancer Survivors Participating in the ¡Mi Vida Saludable! Trial

Abstract

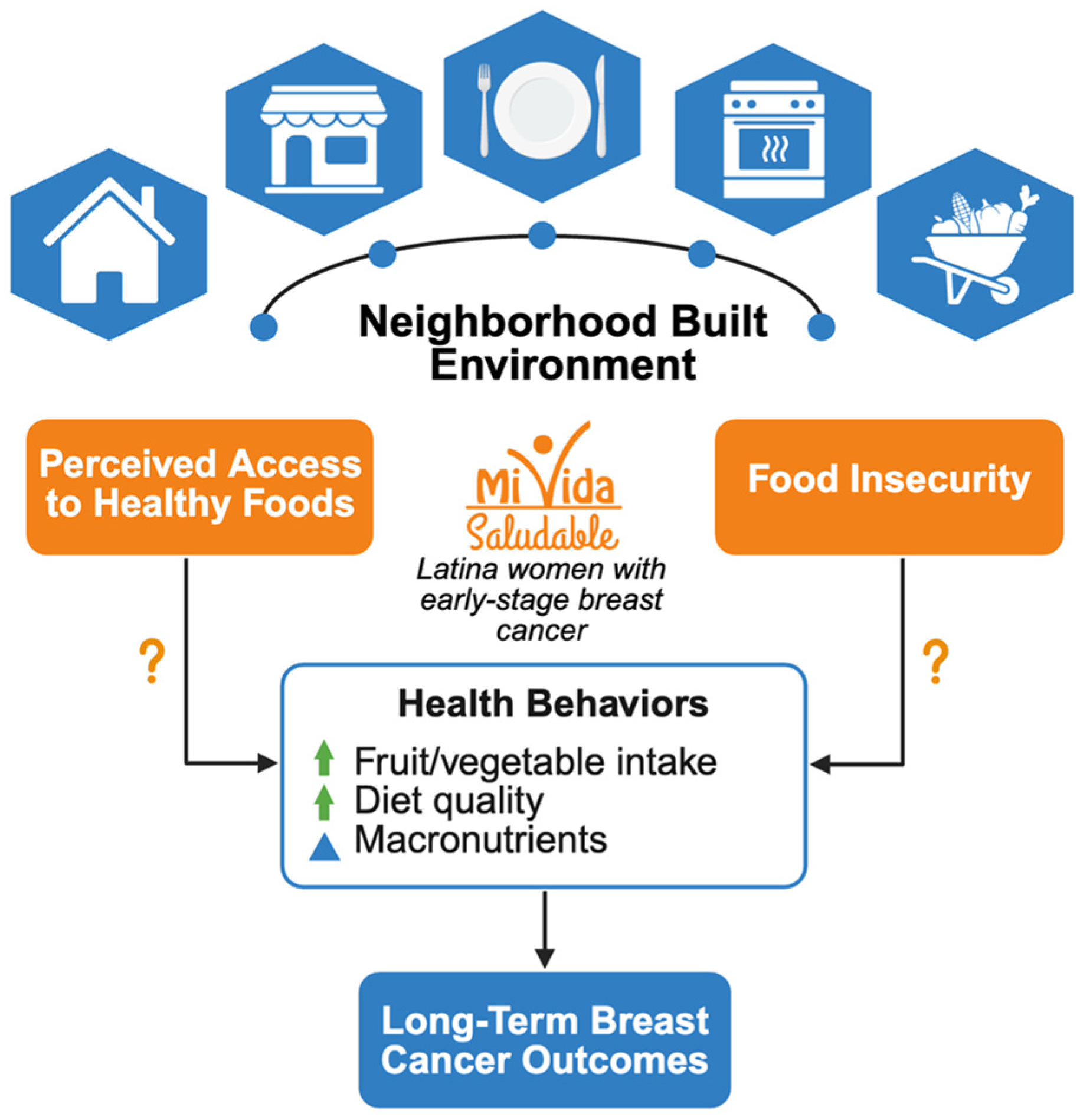

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Data Collection and Measures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

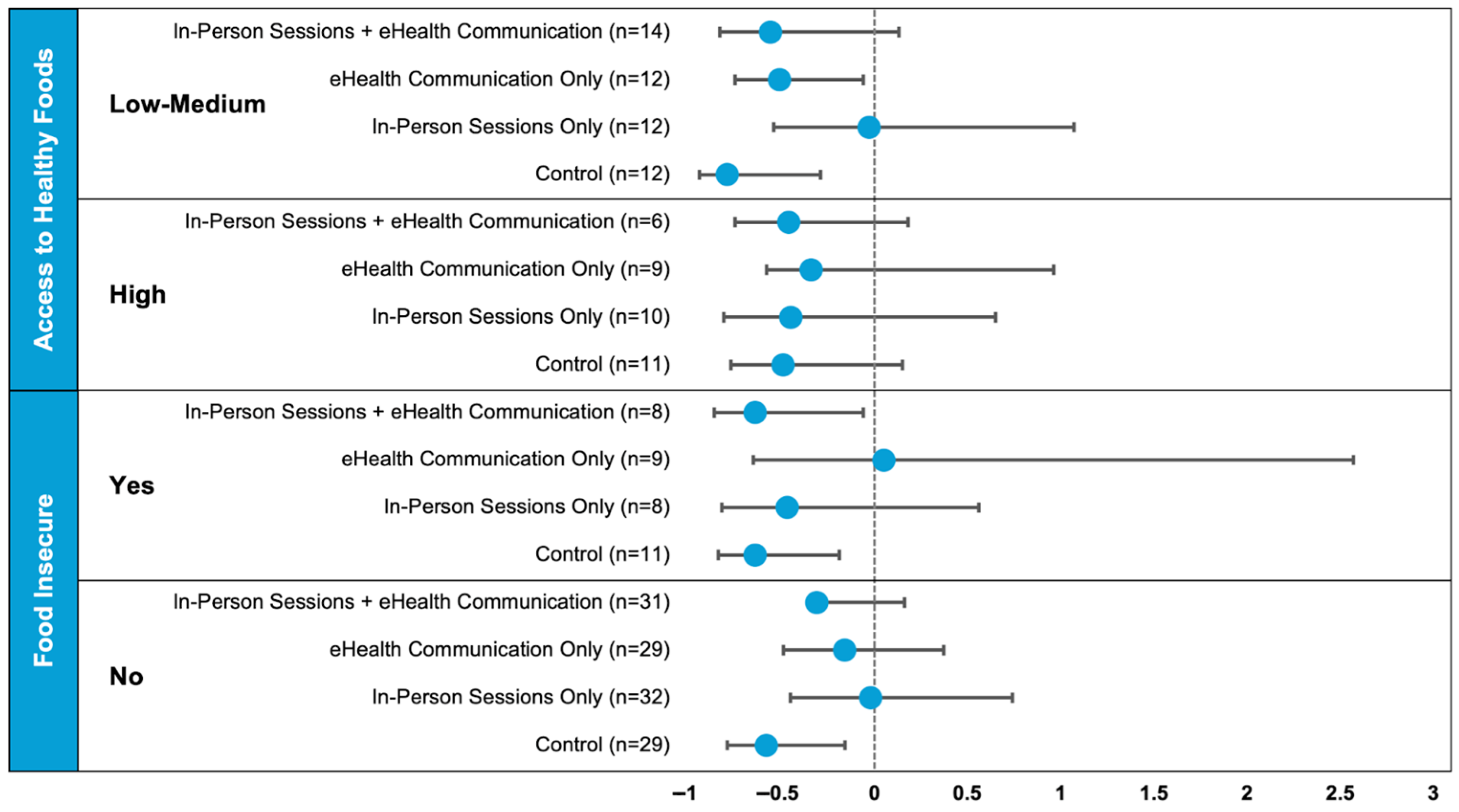

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. General Discussion

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | American Cancer Society |

| AHF | Access to healthy foods |

| AICR | American Institute for Cancer Research |

| BC | Breast cancer |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BRFSS | Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System |

| FI | Food insecurity |

| FV | Fruit–vegetable intake |

| HEI-2015 | Health Eating Index (2015) |

| MiVS | ¡Mi Vida Saludable! |

| MVPA | Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity |

| NDSR | Nutrition Data System for Research |

| SASH | Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| US | United States |

References

- Miller, K.D.; Ortiz, A.P.; Pinheiro, P.S.; Bandi, P.; Minihan, A.; Fuchs, H.E.; Tyson, D.M.; Tortolero-Luna, G.; Fedewa, S.A.; Jemal, A.M.; et al. Cancer statistics for the us Hispanic/Latino population. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, S.L.; Martinez, M.E.; Li, C.I. Disparities in breast cancer characteristics and outcomes by race/ethnicity. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 127, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.I. Racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer stage, treatment, and survival in the United States. Ethn. Dis. 2005, 15, S5–S9. [Google Scholar]

- Kish, J.K.; Yu, M.; Percy-Laurry, A.; Altekruse, S.F. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer survival by neighborhood socioeconomic status in surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) registries. J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. Monogr. 2014, 2014, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.Y.; Walker, G.V.; Grant, S.R.; Allen, P.K.; Jiang, J.; Guadagnolo, B.A.; Smith, B.D.; Koshy, M.; Rusthoven, C.G.; Mahmood, U. Insurance status and racial disparities in cancer-specific mortality in the United States: A population-based analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2017, 26, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.; Lynch, J.; Meersman, S.C.; Breen, N.; Davis, W.W.; Reichman, M.C. Trends in area-socioeconomic and race-ethnic disparities in breast cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis, screening, mortality, and survival among women ages 50 years and over (1987–2005). Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouri, E.M.; He, Y.; Winer, E.P.; Keating, N.L. Influence of birthplace on breast cancer diagnosis and treatment for Hispanic women. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 121, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Hernandez, A.; Thompson, C.; Choi, S.; Westrick, A.; Stoler, J.; Antoni, M.H.; Rojas, K.; Kesmodel, S.; Figueroa, M.E.; et al. Neighborhood disadvantage and breast cancer–specific survival. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e238908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, L.; Canchola, A.J.; Spiegel, D.; Ladabaum, U.; Haile, R.; Gomez, S.L. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer survival: The contribution of tumor, sociodemographic, institutional, and neighborhood characteristics. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, D.J.; Lin, W.Y.; Coffey, M. The role of Hispanic race/ethnicity and poverty in breast cancer survival. P. R. Health Sci. J. 1995, 14, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.C.; Handley, D.; Elsaid, M.I.; Fisher, J.L.; Plascak, J.J.; Anderson, L.; Tsung, C.; Beane, J.; Pawlik, T.M.; Obeng-Gyasi, S. Persistent neighborhood poverty and breast cancer outcomes. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2427755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, S.E.; Borrell, L.N.; Brown, D.; Rhoads, G. A local area analysis of racial, ethnic, and neighborhood disparities in breast cancer staging. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 3024–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, C.; Daniel, C.R.; Tirado-Gómez, M.; Gonzalez-Mercado, V.; Vallejo, L.; Lozada, J.; Ortiz, A.; Hughes, D.C.; Basen-Engquist, K. Dietary patterns in Puerto Rican and Mexican-American breast cancer survivors: A pilot study. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2017, 19, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, R.A.; Vallejo, L.; Hughes, D.C.; Gonzalez, V.; Tirado-Gomez, M.; Basen-Engquist, K. Mexican-American and Puerto Rican breast cancer survivors′ perspectives on exercise: Similarities and differences. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2012, 14, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; Tirado, M.; Hughes, D.C.; Gonzalez, V.; Song, J.; Mama, S.K.; Basen-Engquist, K. Relationship between physical activity, disability, and physical fitness profile in sedentary Latina breast cancer survivors. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2018, 34, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farvid, M.S.; Barnett, J.B.; Spence, N.D. Fruit and vegetable consumption and incident breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, E.; Wong, C.P.; Bouranis, J.A.; Shannon, J.; Zhang, Z. Cruciferous vegetables, bioactive metabolites, and microbiome for breast cancer prevention. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2025, 45, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokbel, K.; Mokbel, K. Chemoprevention of breast cancer with vitamins and micronutrients: A concise review. In Vivo 2019, 33, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, C.L.; Thomson, C.A.; Sullivan, K.R.; Howe, C.L.; Kushi, L.H.; Caan, B.J.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Bandera, E.V.; Wang, Y.; Robien, K.; et al. American cancer society nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 230–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torres, M.; Contento, I.; Koch, P.; Tsai, W.-Y.; Gaffney, A.O.; Marín-Chollom, A.M.; Shi, Z.; Ulanday, K.T.; Shen, H.; Hershman, D.; et al. Associations between acculturation and weight, diet quality, and physical activity among Latina breast cancer survivors: The ¡mi vida saludable! Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, 1703–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago-Torres, M.; Contento, I.; Koch, P.; Tsai, W.-Y.; Brickman, A.M.; Gaffney, A.O.; Thomson, C.A.; Crane, T.E.; Dominguez, N.; Sepulveda, J.; et al. ¡mi vida saludable! a randomized, controlled, 2 × 2 factorial trial of a diet and physical activity intervention among Latina breast cancer survivors: Study design and methods. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2021, 110, 106524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contento, I.; Paul, R.; Marin-Chollom, A.M.; Gaffney, A.O.; Sepulveda, J.; Dominguez, N.; Gray, H.; Haase, A.M.; Hershman, D.L.; Koch, P.; et al. Developing a diet and physical activity intervention for Hispanic/Latina breast cancer survivors. Cancer Control 2022, 29, 10732748221133987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverria, S.E.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Link, B.G. Reliability of self-reported neighborhood characteristics. J. Urban Health 2004, 81, 682–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, S.J.; Bialostosky, K.; Hamilton, W.L.; Briefel, R.R. The effectiveness of a short form of the household food security scale. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1231–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. Protocol: Food Insecurity. PhenX Toolkit. Available online: https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/protocols/view/270301 (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- USDA. Six-Item Short Form of the Food Security Survey Module, Questions hh3, hh4, ad1, ad1a, ad2 and ad3; USDA Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Schakel, S.F.; Sievert, Y.A.; Buzzard, I.M. Sources of data for developing and maintaining a nutrient database. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1988, 88, 1268–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schakel, S.F.; Buzzard, I.; Gebhardt, S.E. Procedures for estimating nutrient values for food composition databases. J. Food Compos. Anal. 1997, 10, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schakel, S.F. Maintaining a nutrient database in a changing marketplace: Keeping pace with changing food products—A research perspective. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2001, 14, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs-Smith, S.M.; Pannucci, T.E.; Subar, A.F.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Lerman, J.L.; Tooze, J.A.; Wilson, M.M.; Reedy, J. Update of the healthy eating index: HEI-2015. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, G.; Sabogal, F.; Marin, B.V.; Otero-Sabogal, R.; Perez-Stable, E.J. Development of a short acculturation scale for hispanics. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1987, 9, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkhchi, P.; Dehkordy, S.F.; Carlos, R.C. Housing and food insecurity, care access, and health status among the chronically ill: An analysis of the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gany, F.; Leng, J.; Ramirez, J.; Phillips, S.; Aragones, A.; Roberts, N.; Mujawar, M.I.; Costas-Muñiz, R. Health-related quality of life of food-insecure ethnic minority patients with cancer. J. Oncol. Pract. 2015, 11, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Praditsorn, P.; Purnamasari, S.D.; Sranacharoenpong, K.; Arai, Y.; Sundermeir, S.M.; Gittelsohn, J.; Hadi, H.; Nishi, N. Measures of perceived neighborhood food environments and dietary habits: A systematic review of methods and associations. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, C.E.; Sorensen, G.; Subramanian, S.; Kawachi, I. The local food environment and diet: A systematic review. Health Place 2012, 18, 1172–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penchansky, R.; Thomas, J.W. The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med. Care 1981, 19, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feathers, A.; Aycinena, A.C.; Lovasi, G.S.; Rundle, A.; Gaffney, A.O.; Richardson, J.; Hershman, D.; Koch, P.; Contento, I.; Greenlee, H. Food environments are relevant to recruitment and adherence in dietary modification trials. Nutr. Res. 2015, 35, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, K.M.; Ranjit, N.; Salvo, D.; Nielsen, A.; Kaliszewski, C.; Hoelscher, D.M.; Berg, A.E.v.D. Association between fresh fruit and vegetable consumption and purchasing behaviors, food insecurity status and geographic food access among a lower-income, racially/ethnically diverse cohort in central texas. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucan, S.C.; Hillier, A.; Schechter, C.B.; Glanz, K. Objective and self-reported factors associated with food-environment perceptions and fruit-and-vegetable consumption: AS multilevel analysis. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, E47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.A.; Webber, E.M.; Martin, A.M.; Henninger, M.L.; Eder, M.L.; Lin, J.S. Preventive services for food insecurity: Evidence report and systematic review for the us preventive services task force. JAMA 2025, 333, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Delahanty, L.M.; Terranova, J.; Steiner, B.; Ruazol, M.P.; Singh, R.; Shahid, N.N.; Wexler, D.J. Medically tailored meal delivery for diabetes patients with food insecurity: A randomized cross-over trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, M.D.; Wang, J.; Hankinson, S.E.; Tamimi, R.M.; Chen, W.Y. Protein intake and breast cancer survival in the nurses’ health study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivoltsis, A.; Cervigni, E.; Trapp, G.; Knuiman, M.; Hooper, P.; Ambrosini, G.L. Food environments and dietary intakes among adults: Does the type of spatial exposure measurement matter? A systematic review. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2018, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenk, S.N.; Mentz, G.; Schulz, A.J.; Johnson-Lawrence, V.; Gaines, C.R. Longitudinal associations between observed and perceived neighborhood food availability and body mass index in a multiethnic urban sample. Health Educ. Behav. 2017, 44, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerceo, E.; Sharma, E.; Boguslavsky, A.; Rachoin, J.-S. Impact of food environments on obesity rates: A state-level analysis. J. Obes. 2023, 2023, 5052613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alber, J.M.; Green, S.H.; Glanz, K. Perceived and observed food environments, eating behaviors, and bmi. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 54, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.P.; Bray, M.S.; Mcfarlin, B.K.; Ellis, K.J.; Sailors, M.H.; Jackson, A.S. Ethnic bias in anthropometric estimates of DXA abdominal fat. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1785–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deurenberg, P.; Deurenberg-Yap, M. Validity of body composition methods across ethnic population groups. Acta Diabetol. 2003, 56, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, C.H.; Aoki, R.; Kushi, L.H.; Torres, J.M.; Morey, B.N.; Gomez, S.; Caan, B.; Canchola, A.J.; Alexeeff, S. Associations between immigrant status and dietary patterns in enclave, a pooled, observational study of women diagnosed with breast cancer. J. Nutr. 2025, 155, 2916–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, R.-L.; Alexeeff, S.E.; Caan, B.J.; Kushi, L.H.; Gomez, S.L.; Torres, J.M.; Canchola, A.J.; Morey, B.N.; Kroenke, C.H. Nativity and healthy lifestyle index in a pooled cohort of female breast cancer survivors from northern california. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2025, 34, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Access to Healthy Foods (n = 86) | Food Insecure (n = 157) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Low–Medium | High | p | Yes | No | p |

| N (%) | 50 (58) | 36 (42) | 36 (23) | 121 (77) | ||

| Randomization arm, n (%) | 0.66 | 0.85 | ||||

| In-person sessions + eHealth communication | 14 (28) | 6 (17) | 8 (22) | 31 (26) | ||

| eHealth communication only | 12 (24) | 9 (25) | 9 (25) | 29 (24) | ||

| In-person sessions only | 12 (24) | 10 (28) | 8 (22) | 32 (27) | ||

| Control | 12 (24) | 11 (31) | 11 (31) | 29 (24) | ||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 53.2 (8.6) | 59.4 (9.6) | <0.01 | 56.5 (7.9) | 57.0 (10.7) | 0.79 |

| Education level, n (%) | 0.43 | 0.24 | ||||

| High school graduate/GED or less | 21 (42) | 19 (53) | 21 (58) | 53 (44) | ||

| Some college | 15 (30) | 11 (31) | 9 (25) | 33 (27) | ||

| College graduate or more | 14 (28) | 6 (17) | 6 (17) | 35 (29) | ||

| Annual household income, n (%) | 0.84 | 0.31 | ||||

| $0–$15,000 | 26 (55) | 22 (61) | 21 (60) | 63 (53) | ||

| $15,001–$30,000 | 10 (21) | 6 (17) | 8 (23) | 21 (18) | ||

| More than $30,000 | 11 (23) | 8 (22) | 6 (17) | 36 (30) | ||

| Has paid employment (full or part-time), n (%) | 20 (41) | 12 (33) | 0.48 | 14 (40) | 47 (39) | 0.90 |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.76 | <0.01 | ||||

| Married/living with partner/common law | 18 (36) | 12 (33) | 8 (22) | 53 (44) | ||

| Separated/divorced | 19 (38) | 13 (36) | 10 (28) | 43 (36) | ||

| Widowed | 2 (4) | 3 (8) | 2 (6) | 6 (5) | ||

| Single | 11 (22) | 8 (22) | 16 (44) | 19 (16) | ||

| Participates in EBT/SNAP or WIC, n (%) | 29 (58) | 19 (53) | 0.63 | 22 (61) | 58 (48) | 0.17 |

| Is food insecure, n (%) | 14 (29) | 7 (19) | 0.34 | --- | --- | --- |

| Number in household, mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.3) | 2.9 (2.1) | 0.92 | 2.9 (1.7) | 2.9 (1.5) | 0.88 |

| Housing type, n (%) | 0.11 | |||||

| Apartment | 46 (92) | 32 (89) | 29 (83) | 106 (88) | ||

| House | 2 (4) | 4 (11) | 2 (6) | 13 (11) | ||

| Single room occupancy | 2 (4) | 0 | 4 (11) | 2 (2) | ||

| Owns home, n (%) | 2 (4) | 5 (14) | 0.11 | 0 | 16 (14) | 0.02 |

| US born, n (%) | 7 (14) | 2 (6) | 0.21 | 6 (17) | 25 (21) | 0.60 |

| SASH acculturation scores (0–5), mean (SD) | ||||||

| Language | 1.8 (0.72) | 1.5 (0.61) | 0.02 | 1.78 (1.08) | 1.8 (0.9) | 0.92 |

| Social | 2.3 (0.70) | 2.1 (0.57) | 0.17 | 2.27 (0.91) | 2.2 (0.6) | 0.73 |

| Overall | 2.1 (0.57) | 1.8 (0.48) | 0.01 | 2.04 (0.89) | 2.0 (0.7) | 0.90 |

| Has high acculturation, n (%) | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 0.75 | 7 (19) | 11 (9) | 0.09 |

| Comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.8) | 1.6 (1.7) | 0.96 | 1.9 (1.5) | 1.4 (1.7) | 0.11 |

| Access to Healthy Foods * (n = 86) | Food Insecure † (n = 157) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diet Measures | Low–Medium | High | p | Yes | No | p |

| FV intake ‡, servings/day | 3.7 (0.5) | 4.4 (0.6) | 0.35 | 4.5 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.3) | 0.16 |

| Energy density, kcal/g | 0.64 (0.03) | 0.61 (0.03) | 0.51 | 0.68 (0.03) | 0.62 (0.02) | 0.14 |

| Total caloric intake, kcal | 1150 (51) | 1173 (61) | 0.78 | 1200 (74) | 1192 (40) | 0.93 |

| Total carbohydrates, g | 160.8 (8.1) | 157.3 (9.6) | 0.79 | 160.9 (9.8) | 160.7 (5.3) | 0.99 |

| Total protein, g | 45.3 (2.2) | 52.8 (2.6) | 0.04 | 52.6 (3.6) | 51.2 (2.0) | 0.75 |

| Total sugars, g | 62.0 (4.4) | 63.4 (5.2) | 0.85 | 65.5 (5.1) | 62.6 (2.7) | 0.61 |

| Total dietary fiber, g | 15.6 (1.0) | 16.4 (1.2) | 0.64 | 15.7 (1.3) | 16.0 (0.7) | 0.87 |

| Total fat, g | 38.9 (2.3) | 38.2 (2.7) | 0.84 | 39.8 (3.5) | 40.7 (1.9) | 0.83 |

| Total monounsaturated fatty acids, g | 14.9 (1.0) | 15.5 (1.1) | 0.68 | 14.6 (1.3) | 15.6 (0.7) | 0.51 |

| Total polyunsaturated fatty acids, g | 8.4 (0.6) | 8.0 (0.7) | 0.67 | 9.1 (0.9) | 8.8 (0.5) | 0.78 |

| Total saturated fatty acids, g | 12.3 (0.9) | 11.4 (1.0) | 0.53 | 12.5 (1.2) | 12.6 (0.6) | 0.97 |

| Total trans-fatty acids, g | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.98 | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.77 |

| HEI 2015 | 70.4 (1.7) | 72.4 (2.0) | 0.46 | 66.5 (2.2) | 70.5 (1.2) | 0.11 |

| Anthropometric Measures | ||||||

| Weight, kg | 74.8 (2.1) | 73.3 (2.4) | 0.66 | 77.9 (2.5) | 71.8 (1.3) | 0.03 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.8 (0.7) | 29.7 (0.9) | 0.93 | 31.3 (0.9) | 29.2 (0.5) | 0.05 |

| Low–Medium AHF (n = 50) | High AHF (n = 36) | |||

| 6-Month D | 12-Month D | 6-Month D | 12-Month D | |

| Estimate (95% CI) | Estimate (95% CI) | Estimate (95% CI) | Estimate (95% CI) | |

| FV intake, servings/day †,‡ | −19% (−41%, +12%) | −32% (−51%, −7%) | −3% (−25%, +26%) | −17% (−40%, +13%) |

| Energy density, kcal/g § | −0.002 (−0.08, 0.08) | −0.05 (−0.11, 0.01) | 0.03 (−0.04, 0.10) | 0.06 (0.003, 0.12) |

| Total caloric intake, kcal | −109.4 (−228.1, 9.3) | −129.0 (−244.5, −13.4) | 15.9 (−96.8, 128.7) | 13.1 (−107.2, 133.5) |

| Total carbohydrates, g § | −18.7 (−38.2, 0.8) | −26.7 (−45.0, −8.5) | 5.8 (−11.2, 22.9) | 6.8 (−11.4, 25.1) |

| Total protein, g | −0.2 (−5.5, 5.2) | 5.2 (−0.2, 10.6) | −0.2 (−7.7, 7.4) | −0.8 (−8.4, 6.8) |

| Total sugars, g § | −7.5 (−17.5, 2.4) | −16.8 (−26.1, −7.5) | −3.1 (−12.7, 6.4) | 1.0 (−9.8, 11.9) |

| Total fat, g | −4.7 (−9.4, 0.1) | −5.8 (−10.6, −1.1) | −0.2 (−5.5, 5.1) | −1.0 (−7.1, 5.1) |

| HEI 2015 | −0.9 (−5.7, 3.8) | 0.7 (−3.0, 4.4) | 0.8 (−3.7, 5.3) | −3.3 (−8.0, 1.4) |

| BMI, kg/m †,§ | −0.07 (−0.5, 0.3) | −0.3 (−0.7, 0.2) | 0.4 (0.1, 0.8) | 0.3 (0.0, 0.6) |

| Food Insecure (n = 36) | Not Food Insecure (n = 121) | |||

| 6-Month D | 12-Month D | 6-Month D | 12-Month D | |

| Estimate (95% CI) | Estimate (95% CI) | Estimate (95% CI) | Estimate (95% CI) | |

| FV intake, servings/day †,‡,§,|| | −30% (−50%, −4%) | −39% (−57%, −14%) | 2% (−14%, +20%) | −10% (−25%, +8%) |

| Energy density, kcal/g | 0.01 (−0.09, 0.11) | −0.06 (−0.12, 0.01) | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.05) | −0.02 (−0.05, 0.02) |

| Total caloric intake, kcal | −96.2 (−306.1, 113.7) | −120.9 (−279.9, 38.2) | −55.9 (−124.7, 13.0) | −44.3 (−120.7, 32.1) |

| Total carbohydrates, g | −4.0 (−35.8, 27.7) | −18.2 (−39.8, 3.4) | −5.3 (−15.2, 4.6) | −3.2 (−14.3, 7.9) |

| Total protein, g | −8.4 (−15.7, −1.0) | −3.8 (−11.3, 3.7) | −0.8 (−4.9, 3.3) | 1.9 (−2.1, 5.9) |

| Total sugars, g | −1.2 (−19.0, 16.6) | −11.7 (−23.2, −0.3) | −3.0 (−8.0, 2.0) | −4.8 (−10.8, 1.1) |

| Total fat, g | −4.8 (−13.0, 3.5) | −4.0 (−11.0, 3.0) | −3.9 (−7.2, −0.7) | −4.8 (−8.6, −1.0) |

| HEI 2015 | 2.1 (−1.9, 6.1) | 1.5 (−2.5, 5.5) | 1.2 (−1.5, 3.9) | 0.09 (−2.3, 2.5) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | −0.19 (−0.73, 0.35) | −0.11 (−0.61, 0.39) | −0.24 (−0.48, −0.01) | −0.01 (−0.55, 0.54) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kadro, Z.O.; Rillamas-Sun, E.; Langley, B.O.; Meisner, A.; Contento, I.; Koch, P.A.; Ogden Gaffney, A.; Hershman, D.L.; Greenlee, H. Associations Between the Food Environment and Food Insecurity on Fruit, Vegetable, and Nutrient Intake, and Body Mass Index, Among Urban-Dwelling Latina Breast Cancer Survivors Participating in the ¡Mi Vida Saludable! Trial. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3950. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243950

Kadro ZO, Rillamas-Sun E, Langley BO, Meisner A, Contento I, Koch PA, Ogden Gaffney A, Hershman DL, Greenlee H. Associations Between the Food Environment and Food Insecurity on Fruit, Vegetable, and Nutrient Intake, and Body Mass Index, Among Urban-Dwelling Latina Breast Cancer Survivors Participating in the ¡Mi Vida Saludable! Trial. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3950. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243950

Chicago/Turabian StyleKadro, Zachary O., Eileen Rillamas-Sun, Blake O. Langley, Allison Meisner, Isobel Contento, Pamela A. Koch, Ann Ogden Gaffney, Dawn L. Hershman, and Heather Greenlee. 2025. "Associations Between the Food Environment and Food Insecurity on Fruit, Vegetable, and Nutrient Intake, and Body Mass Index, Among Urban-Dwelling Latina Breast Cancer Survivors Participating in the ¡Mi Vida Saludable! Trial" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3950. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243950

APA StyleKadro, Z. O., Rillamas-Sun, E., Langley, B. O., Meisner, A., Contento, I., Koch, P. A., Ogden Gaffney, A., Hershman, D. L., & Greenlee, H. (2025). Associations Between the Food Environment and Food Insecurity on Fruit, Vegetable, and Nutrient Intake, and Body Mass Index, Among Urban-Dwelling Latina Breast Cancer Survivors Participating in the ¡Mi Vida Saludable! Trial. Nutrients, 17(24), 3950. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243950