A Multi-Omics Study Reveals the Active Components and Therapeutic Mechanism of Erhuang Quzhi Formula for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical and Reagents

2.2. Preparation of EQF Decoction

2.3. Preparation of EQF-Containing Serum

2.4. Analysis of EQF Decoction and EQF-Containing Serum Components

2.5. Screening of Active Components and Targets of EQF Against NAFLD

2.6. Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Construction

2.7. Molecular Docking

2.8. Animal Experiment

2.9. Biochemical Analysis

2.10. Histological Staining

2.11. Metabolomic Analysis

2.12. Lipidomic Analysis

2.13. Real-Time Quantitative PCR Analysis

2.14. Western Blot Analysis

2.15. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of EQF Components and Serum Absorption Components by UPLC-Q-TOF-MS

3.2. Network Pharmacology Analysis and Verification of EQF in the Treatment of NAFLD

3.3. Molecular Docking Validation of EQF Components and Targets

3.4. The Therapeutic Effect of EQF on NAFLD Model

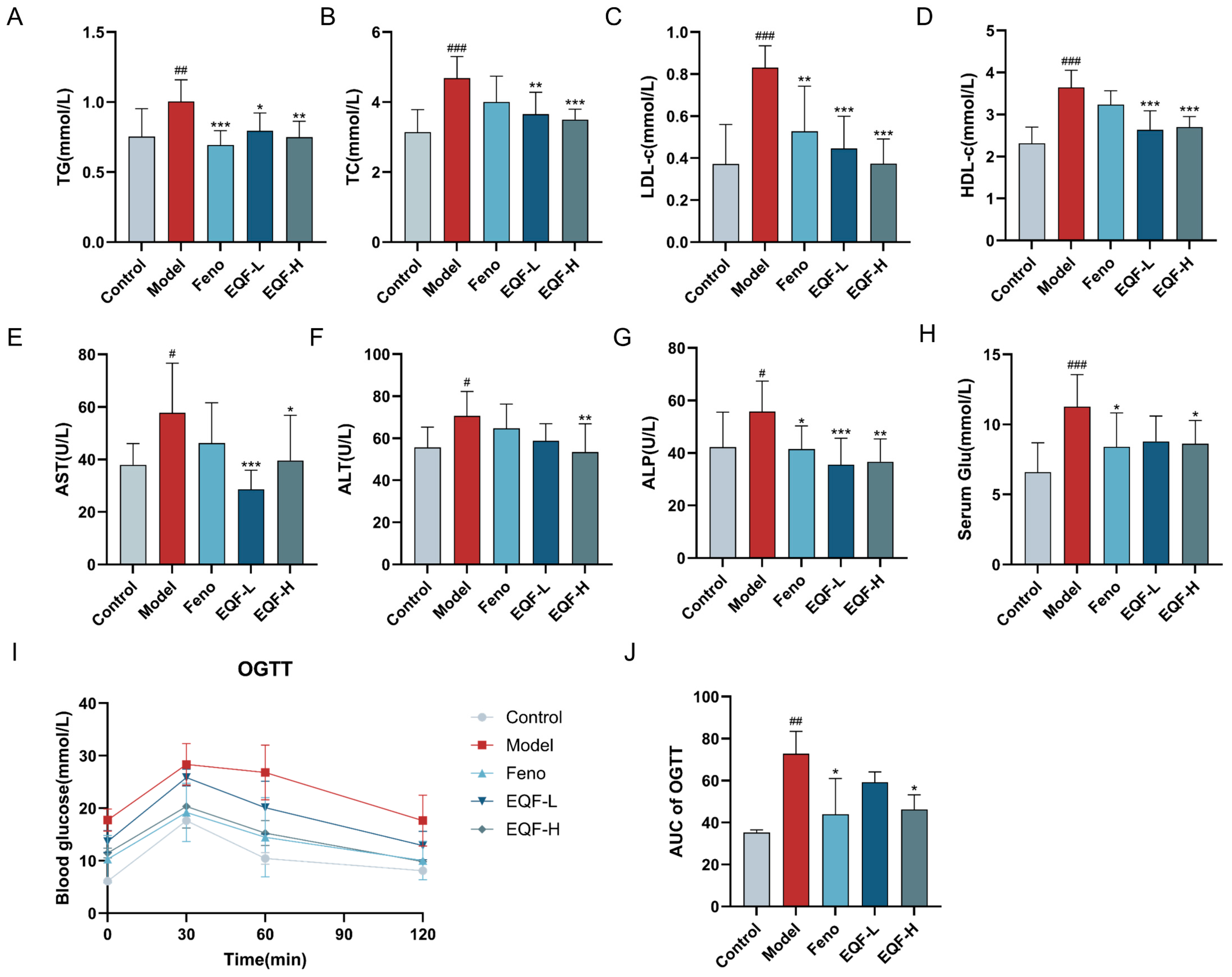

3.5. Effects of EQF on Metabolic Parameters and Liver Function in NAFLD Mice

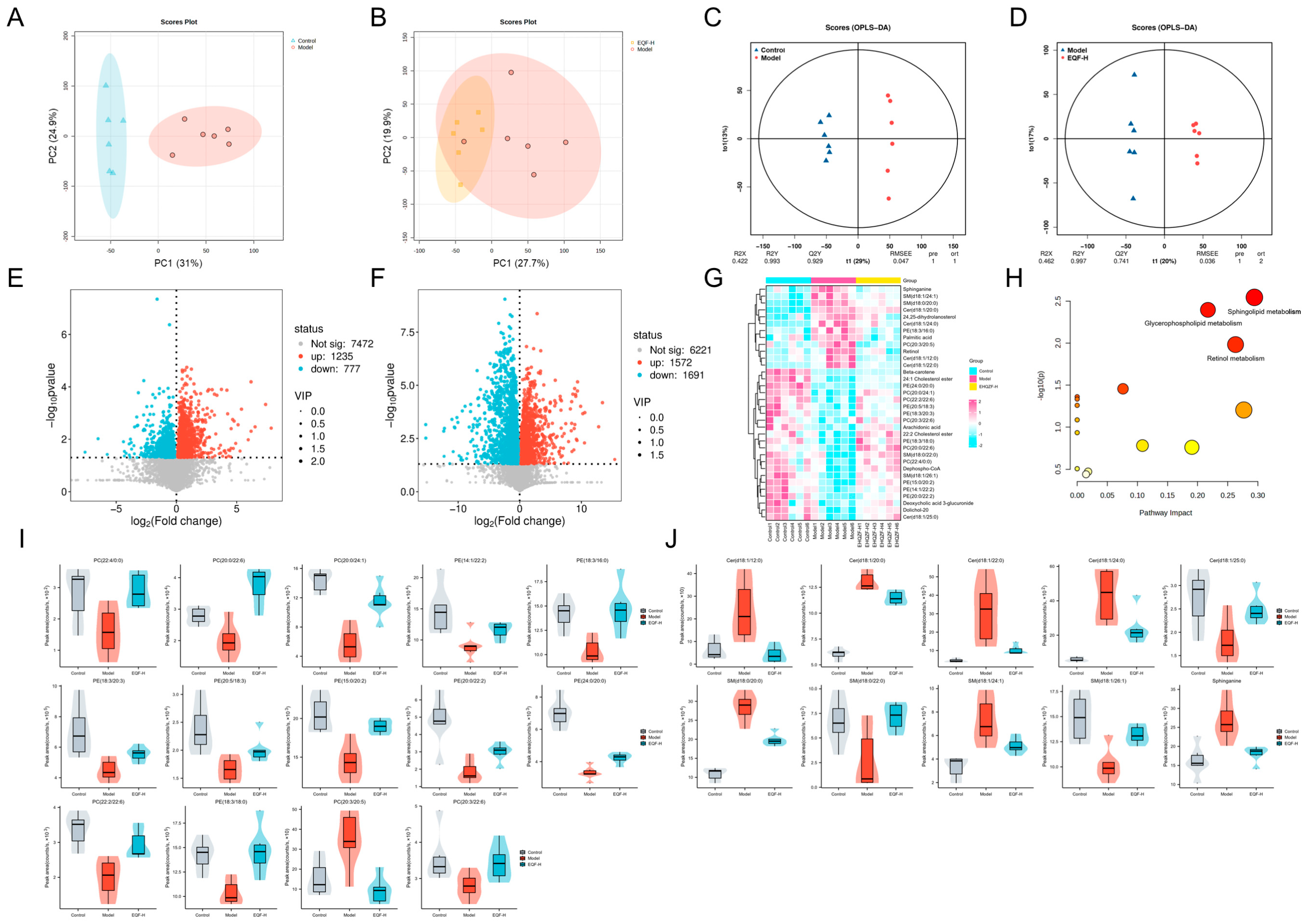

3.6. Regulatory Effects of EQF on Hepatic Lipids

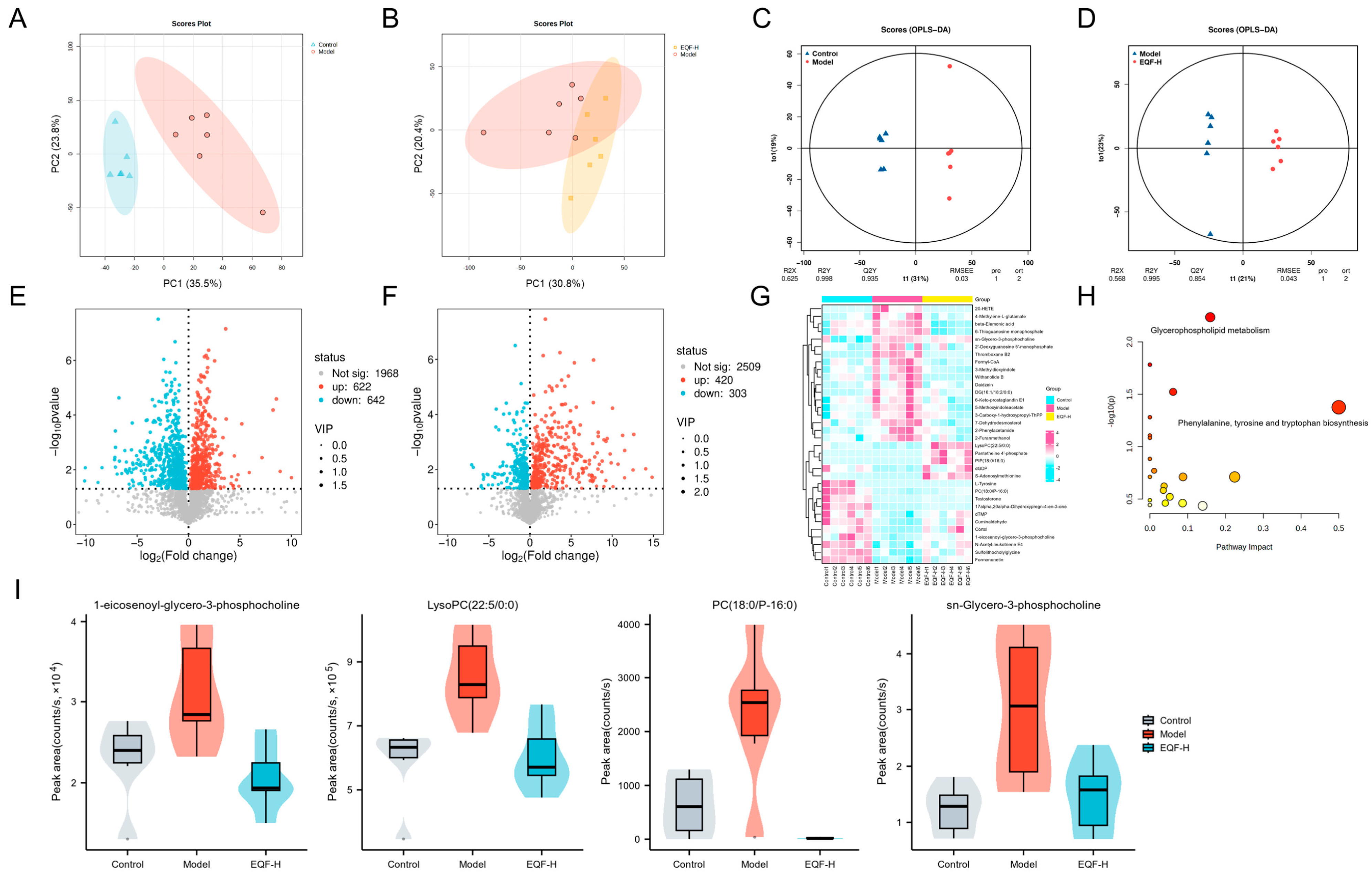

3.7. Regulatory Effects of EQF on Hepatic Metabolism

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic acid |

| BCL-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| CASP3 | Caspase3 |

| EQF | Erhuang Quzhi Formula |

| ESR1 | Estrogen receptor 1 |

| FC | Fold change |

| GLU | Glucose |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MMP9 | Matrix metalloproteinase 9 |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NASH | Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis |

| ND | Normal diet |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal projections to latent structures–discriminant analysis |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PPI | Protein–protein interaction |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| RT-qPCR | Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| SDS | Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese medicine |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| UCP1 | Uncoupling protein 1 |

| UPLC-Q-TOF-MS | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| VIP | Variable importance in projection |

| VLDL | Very-low-density lipoprotein |

References

- Eslam, M.; Sanyal, A.J.; George, J.; International Consensus Panel. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1999–2014.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiman, Y.; Duarte-Rojo, A.; Rinella, M.E. Fatty Liver Disease: Diagnosis and Stratification. Annu. Rev. Med. 2022, 73, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, T.G.; Rinella, M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease 2020: The State of the Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1851–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, S.A.; Kountouras, J.; Mantzoros, C.S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: From pathophysiology to therapeutics. Metabolism 2019, 92, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Effenberger, M. From NAFLD to MAFLD: When pathophysiology succeeds. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M.; Ratziu, V.; George, J. Yet more evidence that MAFLD is more than a name change. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 977–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Adolph, T.E.; Moschen, A.R. Multiple Parallel Hits Hypothesis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Revisited After a Decade. Hepatology 2021, 73, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Anirvan, P.; Reddy, K.R.; Conjeevaram, H.S.; Marchesini, G.; Rinella, M.E.; Madan, K.; Petroni, M.L.; Al-Mahtab, M.; Caldwell, S.H.; et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Not time for an obituary just yet! J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 972–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, S.A.; Kechagias, S.; Tsochatzis, E.A. Review article: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular diseases: Associations and treatment considerations. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 54, 1013–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.Q. Yuan Jinqi’s Medical Essays, 1st ed.; Ancient Chinese Medical Books Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 336–342. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Ma, Y.; Chen, W. Active ingredients of Erhuang Quzhi Granules for treating non-alcoholic fatty liver disease based on the NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway. Fitoterapia 2023, 171, 105704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiha, G.; Mousa, N. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis or metabolic-associated fatty liver: Time to change. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2021, 10, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Prediction and verification of the active ingredients and potential targets of Erhuang Quzhi Granules on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease based on network pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 311, 116435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Chen, W.; Wu, X.; Li, C.; Gao, Y.; Qin, D. Active Targets and Potential Mechanisms of Erhuang Quzhi Formula in Treating NAFLD: Network Analysis and Experimental Assessment. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2024, 82, 3297–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.P.; Xu, D.Q.; Yue, S.J.; Chen, Y.Y.; Fu, R.J.; Bai, X. Modern research thoughts and methods on bio-active components of TCM formulae. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2022, 20, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J.; Ren, J.L.; Zhang, A.H.; Sun, H.; Yan, G.L.; Han, Y.; Liu, L. Novel applications of mass spectrometry-based metabolomics in herbal medicines and its active ingredients: Current evidence. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2019, 38, 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhang, A.; Yan, G.; Wang, X.J. Chinmedomics, a new strategy for evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of herbal medicines. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 216, 107680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Su, H.; Chen, H.; Tang, X.; Li, W.; Huang, A.; Fang, G.; Chen, Q.; Luo, Y.; Pang, Y. Integrated serum pharmacochemistry and network pharmacology to explore the mechanism of Yi-Shan-Hong formula in alleviating chronic liver injury. Phytomedicine 2024, 128, 155439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Bagarolo, G.I.; Thoroe-Boveleth, S.; Jankowski, J. “Lipidomics”: Mass spectrometric and chemometric analyses of lipids. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 159, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, G.; Saba, F.; Cassader, M.; Gambino, R. Lipidomics in pathogenesis, progression and treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): Recent advances. Prog. Lipid Res. 2023, 91, 101238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sigon, G.; Mullish, B.H.; Wang, D.; Sharma, R.; Manousou, P.; Forlano, R. Applying Lipidomics to Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Clinical Perspective. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhan, C.; Yang, C.; Fernie, A.R.; Luo, J. Metabolomics-centered mining of plant metabolic diversity and function: Past decade and future perspectives. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, B.; Lam, S.M.; Shui, G. Integration of lipidomics and metabolomics for in-depth understanding of cellular mechanism and disease progression. J. Genet. Genom. 2020, 47, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.K.; Catanese, S.; Emond, P.; Corcia, P.; Blasco, H.; Pisella, P.J. Metabolomics and lipidomics approaches in human tears: A systematic review. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2022, 67, 1229–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perakakis, N.; Stefanakis, K.; Mantzoros, C.S. The role of omics in the pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism 2020, 111S, 154320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, J.; Li, J.; Xiang, T.; Xuan, R.; Zhou, Y. Yinchenhao decoction and its active compound rhein ameliorate intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in mice via modulation of intestinal flora. Phytomedicine 2025, 148, 157397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xiao, Q.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, C.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Sun, H.; Liu, H. Schisanhenol ameliorates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease via inhibiting miR-802 activation of AMPK-mediated modulation of hepatic lipid metabolism. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 3949–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Xiong, P.; Cheng, L.; Ma, J.; Wen, Y.; Shen, T.; He, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Integrated network pharmacology, metabolomics, and transcriptomics of Huanglian-Hongqu herb pair in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 325, 117828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Tilg, H. NAFLD and increased risk of cardiovascular disease: Clinical associations, pathophysiological mechanisms and pharmacological implications. Gut 2020, 69, 1691–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease—A global public health perspective. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paternostro, R.; Trauner, M. Current treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 292, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, Z.; Gerard, P. The links between the gut microbiome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 1541–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Yan, N.; Wang, P.; Xia, Y.; Hao, H.; Wang, G.; Gonzalez, F.J. Herbal drug discovery for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Shen, X.; Li, N.; Huang, W.; Li, X.; Ye, Q.; Ruan, Y.; Li, R.; Zhu, H.; Xu, L.; et al. Qidong Huoxue decoction protects against acute lung injury by promoting SIRT1-mediated p300 deacetylation. Phytomedicine 2025, 145, 157064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Liu, B.; Tang, S.; Yasir, M.; Khan, I. The science behind TCM and Gut microbiota interaction-their combinatorial approach holds promising therapeutic applications. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 875513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghe, J.; Priem, D.; Bertrand, M.J.M. Cell death checkpoints in the TNF pathway. Trends Immunol. 2023, 44, 628–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiegs, G.; Horst, A.K. TNF in the liver: Targeting a central player in inflammation. Semin. Immunopathol. 2022, 44, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liang, Y.; Xie, X.; Pan, H.; Cao, M.; Wang, S.; Wu, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; et al. Combination of aloe emodin, emodin, and rhein from Aloe with EDTA sensitizes the resistant Acinetobacter baumannii to polymyxins. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1467607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, L.; Lai, Y. Recent findings regarding the synergistic effects of emodin and its analogs with other bioactive compounds: Insights into new mechanisms. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, Y.; Liu, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Ma, X. Comparative studies on the interaction of nine flavonoids with trypsin. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 238, 118440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.W.; Shi, J.; Huang, C.; Tan, H.Y.; Ning, Z.; Lyu, C.; Xu, Y.; Mok, H.L.; Zhai, L.; Xiang, L.; et al. Integrated metabolomics and serum-feces pharmacochemistry-based network pharmacology to reveal the mechanisms of an herbal prescription against ulcerative colitis. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 178, 108775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Feng, Y.D.; Zou, Y.L.; Xiao, Y.H.; Wu, J.J.; Yang, Y.R.; Jiang, X.X.; Wang, L.; Xu, W. Integrating serum pharmacochemistry, network pharmacology and untargeted metabolomics strategies to reveal the material basis and mechanism of action of Feining keli in the treatment of chronic bronchitis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 335, 118643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; He, X.; Shu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, G. Integrating serum pharmacochemistry, network pharmacology, and metabolomics to explore the protective mechanism of Hua-Feng-Dan in ischemic stroke. Phytomedicine 2025, 148, 157251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tian, Z.; Zhao, D.; Liang, Y.; Dai, S.; Liu, M.; Hou, S.; Dong, X.; Zhaxinima; Yang, Y. Effects of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Lipid Profiles in Adults: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 108, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Kao, T.C.; Hu, S.; Li, Y.; Feng, W.; Guo, X.; Zeng, J.; Ma, X. Protective role of baicalin in the dynamic progression of lung injury to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A meta-analysis. Phytomedicine 2023, 114, 154777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.F.; Tang, F.; Chen, L.; Tan, Y.Z.; Rao, C.L.; Ao, H.; Peng, C. Panax ginseng and its ginsenosides: Potential candidates for the prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced side effects. J. Ginseng Res. 2021, 45, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaki, M.; Bartolomucci, A.; Kawachi, I. The multiple roles of life stress in metabolic disorders. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 10–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson, J.L.; Tatum, S.M.; Holland, W.L.; Summers, S.A. Ceramides are fuel gauges on the drive to cardiometabolic disease. Physiol. Rev. 2024, 104, 1061–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, B.; Summers, S.A. Ceramides in Metabolism: Key Lipotoxic Players. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2021, 83, 303–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, M.; Gordillo, R.; Koliaki, C.; Gancheva, S.; Jelenik, T.; De Filippo, E.; Herder, C.; Markgraf, D.; Jankowiak, F.; Esposito, I.; et al. Specific Hepatic Sphingolipids Relate to Insulin Resistance, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 1235–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Li, Y.; Chowdhury, N.; Yu, H.; Syn, W.K.; Lopes-Virella, M.; Yilmaz, Ö.; Huang, Y. The Presence of Periodontitis Exacerbates Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via Sphingolipid Metabolism-Associated Insulin Resistance and Hepatic Inflammation in Mice with Metabolic Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, M.J.; Trent, M.S. Intermembrane transport: Glycerophospholipid homeostasis of the Gram-negative cell envelope. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 17147–17155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varandas, P.; Cobb, A.J.A.; Segundo, M.A.; Silva, E.M.P. Emergent Glycerophospholipid Fluorescent Probes: Synthesis and Applications. Bioconjug. Chem. 2020, 31, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Fulte, S.; Deng, F.; Chen, S.; Xie, Y.; Chao, X.; He, X.C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Li, F.; et al. Lack of VMP1 impairs hepatic lipoprotein secretion and promotes non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presa, N.; Clugston, R.D.; Lingrell, S.; Kelly, S.E.; Merrill, A.H., Jr.; Jana, S.; Kassiri, Z.; Gómez-Muñoz, A.; Vance, D.E.; Jacobs, R.L.; et al. Vitamin E alleviates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase deficient mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorucci, S.; Marchiano, S.; Urbani, G.; Di Giorgio, C.; Distrutti, E.; Zampella, A.; Biagioli, M. Immunology of bile acids regulated receptors. Prog. Lipid Res. 2024, 95, 101291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Component Name | Detected in Serum | Molecular Formula | Adducts | Expected Mass m/z | Observed | Error (ppm) | tR (min) | Database Match |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Betaine | C5H11NO2 | [M + H]+ | 118.0863 | 118.0862 | 0.8 | 1.03 | √ | |

| 2 | Citric acid | C6H8O7 | [M − H]− | 191.0197 | 191.0198 | −0.5 | 2.10 | √ | |

| 3 | Adenosine | C10H13N5O4 | [M + H]+ | 268.1040 | 268.1040 | 0.0 | 3.74 | √ | |

| 4 | Guanosine | C10H13N5O5 | [M + H]+ | 284.0989 | 284.0991 | −0.7 | 4.61 | √ | |

| 5 | Methyl (1α,3R,4α,5R)-1,3,4,5-tetrahydroxycyclohexanecarboxylate | C8H14O6 | [M − H]− | 205.0718 | 205.0721 | −1.5 | 7.97 | ||

| 6 | Atractyloside A | C21H36O10 | [M + FA − H]− | 493.2300 | 493.2299 | 0.2 | 10.34 | √ | |

| 7 | Coclaurine | C17H19NO3 | [M + H]+ | 286.1439 | 286.1440 | −0.3 | 10.90 | ||

| 8 | Puerarin-4′-O-glucoside | √ | C27H30O14 | [M − H]− | 577.1563 | 577.1562 | 0.2 | 10.94 | |

| 9 | Hirudonucleodisulfide B | C11H10N4O4S2 | [M − H]− | 325.0077 | 325.0060 | 5.2 | 11.02 | ||

| 10 | N-Methylcoclaurine | C18H21NO3 | [M + H]+ | 300.1594 | 300.1598 | −1.3 | 11.14 | ||

| 11 | Catechin | C15H14O6 | [M − H]− | 289.0718 | 289.0716 | 0.7 | 11.39 | √ | |

| 12 | Aloe-emodin-8-glucopyranoside | √ | C21H20O10 | [M − H]− | 431.0984 | 431.0982 | 0.5 | 12.21 | √ |

| 13 | Daidzein-4′,7-diglucoside | √ | C27H30O14 | [M + FA − H]− | 623.1618 | 623.1623 | −0.8 | 12.32 | |

| 14 | 3′-Hydroxypuerarin 7-O-sulfate | √ | C21H20O13S | [M − H]− | 511.0552 | 511.0554 | −0.4 | 13.02 | |

| 15 | Roseoside | C19H30O8 | [M + FA − H]− | 431.1923 | 431.1921 | 0.5 | 13.38 | ||

| 16 | Armepavine | C19H23NO3 | [M + H]+ | 314.1751 | 314.1754 | −1.0 | 13.52 | √ | |

| 17 | 6″-O-Apiofuranosyl-3′-hydroxypuerarin | C26H28O14 | [M − H]− | 563.1406 | 563.1414 | −1.4 | 13.62 | ||

| 18 | N-Norarmepavine | √ | C18H21NO3 | [M + H]+ | 300.1594 | 300.1598 | −1.3 | 13.97 | |

| 19 | Hirudonucleodisulfide A | C10H6N4O4S2 | [M − H]− | 308.9758 | 308.9754 | 1.3 | 14.04 | ||

| 20 | Epicatechin | C15H14O6 | [M − H]− | 289.0718 | 289.0715 | 1.0 | 14.12 | √ | |

| 21 | Puerarin | √ | C21H20O9 | [M − H]− | 415.1035 | 415.1030 | 1.2 | 14.25 | √ |

| 22 | 3′-Methoxypuerarin | √ | C22H22O10 | [M − H]− | 445.1140 | 445.1136 | 0.9 | 15.01 | √ |

| 23 | 6″-O-Xylosylpuerarin | √ | C26H28O13 | [M − H]− | 547.1457 | 547.1459 | −0.4 | 15.14 | |

| 24 | Mirificin | √ | C26H28O13 | [M − H]− | 547.1457 | 547.1455 | 0.4 | 15.54 | |

| 25 | Daidzin | √ | C21H20O9 | [M + FA − H]− | 461.1089 | 461.1092 | −0.7 | 16.69 | √ |

| 26 | 3′-Methoxydaidzin | C22H22O10 | [M + FA − H]− | 491.1195 | 491.1199 | −0.8 | 17.59 | ||

| 27 | 6″-O-Apiofuranosyl-Genistein 8-C-glucoside | √ | C26H28O14 | [M − H]− | 563.1406 | 563.1415 | −1.6 | 18.26 | |

| 28 | Polydatin | √ | C20H22O8 | [M − H]− | 389.1242 | 389.1240 | 0.5 | 18.60 | |

| 29 | Liquiritin | √ | C21H22O9 | [M − H]− | 417.1191 | 417.1187 | 1.0 | 18.68 | √ |

| 30 | Liquiritin apioside | √ | C26H30O13 | [M − H]− | 549.1614 | 549.1610 | 0.7 | 19.04 | |

| 31 | Rutin | C27H30O16 | [M − H]− | 609.1461 | 609.1464 | −0.5 | 19.57 | √ | |

| 32 | Isoquercitrin | √ | C21H20O12 | [M − H]− | 463.0882 | 463.0882 | 0.0 | 20.01 | √ |

| 33 | Nuciferine | √ | C19H21NO2 | [M + H]+ | 296.1645 | 296.1650 | −1.7 | 20.37 | √ |

| 34 | Quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucuronide | √ | C21H18O13 | [M − H]− | 477.0675 | 477.0669 | 1.3 | 20.50 | √ |

| 35 | Isochlorogenic acid B | C25H24O12 | [M − H]− | 515.1195 | 515.1202 | −1.4 | 21.46 | √ | |

| 36 | 6″-O-Malonyldaidzin | C24H22O12 | [M + H]+ | 503.1184 | 503.1195 | −2.2 | 21.46 | ||

| 37 | Salvianolic acid J | C27H22O12 | [M − H]− | 537.1039 | 537.1040 | −0.2 | 21.50 | ||

| 38 | Salvianolic acid D | C20H18O10 | [M − H]− | 417.0827 | 417.0824 | 0.7 | 21.62 | √ | |

| 39 | Isochlorogenic acid A | C25H24O12 | [M − H]− | 515.1195 | 515.1199 | −0.8 | 21.71 | √ | |

| 40 | Rosmarinic acid | C18H16O8 | [M − H]− | 359.0772 | 359.0764 | 2.2 | 22.85 | √ | |

| 41 | Isochlorogenic acid C | C25H24O12 | [M − H]− | 515.1195 | 515.1185 | 1.9 | 23.02 | √ | |

| 42 | 6″-O-Acetyldaidzin | C23H22O10 | [M + H]+ | 459.1286 | 459.1293 | −1.5 | 23.11 | ||

| 43 | Salvianolic acid E | C36H30O16 | [M − H]− | 717.1461 | 717.1460 | 0.1 | 23.59 | √ | |

| 44 | Formononetin glucoside | √ | C22H22O9 | [M + H]+ | 431.1337 | 431.1342 | −1.2 | 23.66 | √ |

| 45 | Lithospermic acid | C27H22O12 | [M − H]− | 537.1039 | 537.1042 | −0.6 | 23.91 | √ | |

| 46 | Daidzein | √ | C15H10O4 | [M − H]− | 253.0506 | 253.0504 | 0.8 | 24.59 | √ |

| 47 | Salvianolic acid B | C36H30O16 | [M − H]− | 717.1461 | 717.1456 | 0.7 | 25.52 | √ | |

| 48 | Morin | C15H10O7 | [M − H]− | 301.0354 | 301.0350 | 1.3 | 26.48 | √ | |

| 49 | Salvianolic acid Y | C36H30O16 | [M − H]− | 717.1461 | 717.1460 | 0.1 | 26.56 | √ | |

| 50 | Emodin 8-O-glucoside | √ | C21H20O10 | [M − H]− | 431.0984 | 431.0986 | −0.5 | 27.15 | √ |

| 51 | Formononetin-7-O-β-D-glucoside-6″-O-malonate | C25H24O12 | [M + H]+ | 517.1341 | 517.1353 | −2.3 | 27.25 | ||

| 52 | Bisdemethoxycurcumin | C19H16O4 | [M − H]− | 307.0976 | 307.0974 | 0.7 | 29.90 | √ | |

| 53 | Emodin-8-O-(6-malonyl)-glucoside | C24H22O13 | [M − H]− | 517.0988 | 517.0991 | −0.6 | 30.17 | ||

| 54 | 22-Hydroxy-licorice saponin G2 | C42H62O18 | [M + H]+ | 855.4009 | 855.4044 | −4.1 | 30.31 | ||

| 55 | Isocurcumin | C21H20O6 | [M + H]+ | 369.1333 | 369.1344 | −3.0 | 30.94 | ||

| 56 | Licorice saponin A3 | √ | C48H72O21 | [M − H]− | 983.4493 | 983.4500 | −0.7 | 31.05 | |

| 57 | Gypenoside XLIII | C54H92O23 | [M + FA − 2H]2− | 599.2997 | 599.3014 | −2.8 | 31.25 | ||

| 58 | Licoricesaponin G2 | √ | C42H62O17 | [M − H]− | 837.3914 | 837.3916 | −0.2 | 31.82 | |

| 59 | 16-Oxoalisol A | √ | C30H48O6 | [M + FA − H]− | 549.3433 | 549.3440 | −1.3 | 32.53 | √ |

| 60 | Gypenoside XLVI | C48H82O19 | [M + FA − H]− | 1007.5432 | 1007.5449 | −1.7 | 32.82 | √ | |

| 61 | 6-Methylrhein | √ | C16H10O6 | [M − H]− | 297.0405 | 297.0403 | 0.7 | 32.87 | |

| 62 | Gypenoside XIX | C54H92O23 | [M − H]− | 1107.5957 | 1107.5982 | −2.3 | 33.03 | ||

| 63 | Uralsaponin U | √ | C42H62O17 | [M − H]− | 837.3914 | 837.3923 | −1.1 | 33.40 | |

| 64 | Rhein | √ | C15H8O6 | [M − H]− | 283.0248 | 283.0247 | 0.4 | 33.58 | √ |

| 65 | Ginsenoside Re | C48H82O18 | [M + FA − H]− | 991.5483 | 991.5525 | −4.2 | 33.91 | √ | |

| 66 | Macedonoside A | C42H62O17 | [M − H]− | 837.3914 | 837.3929 | −1.8 | 34.26 | ||

| 67 | Glycyrrhizic acid | √ | C42H62O16 | [M − H]− | 821.3965 | 821.3973 | −1.0 | 34.39 | √ |

| 68 | Gypenoside VII | C54H92O21 | [M + FA − H]− | 1121.6113 | 1121.6142 | −2.6 | 34.68 | ||

| 69 | Atractylenolide I | C15H18O2 | [M + H]+ | 231.1380 | 231.1386 | −2.6 | 34.97 | √ | |

| 70 | Uralsaponin B | C42H62O16 | [M − H]− | 821.3965 | 821.3970 | −0.6 | 35.34 | ||

| 71 | Ginsenoside Rg2 | C42H72O13 | [M + FA − H]− | 829.4955 | 829.4957 | −0.2 | 36.43 | √ | |

| 72 | Demethoxycyclocurcumin | C20H18O5 | [M − H]− | 337.1081 | 337.1081 | 0.0 | 36.71 | √ | |

| 73 | Curcumin | C21H20O6 | [M + H]+ | 369.1333 | 369.1344 | −3.0 | 37.12 | √ | |

| 74 | Aloe-emodin | √ | C15H10O5 | [M − H]− | 269.0455 | 269.0456 | −0.4 | 37.42 | √ |

| 75 | Alisol C,23-acetate | C32H48O6 | [M + FA − H]− | 573.3433 | 573.3440 | −1.2 | 38.33 | √ | |

| 76 | Alisol A | √ | C30H50O5 | [M + FA − H]− | 535.3640 | 535.3649 | −1.7 | 40.12 | √ |

| 77 | Cryptotanshinone | √ | C19H20O3 | [M + H]+ | 297.1485 | 297.1495 | −3.4 | 40.35 | √ |

| 78 | Torachrysone sulfate | √ | C14H14O7S | [M − H]− | 325.0387 | 325.0386 | 0.3 | 40.42 | |

| 79 | Tanshinone I | C18H12O3 | [M + H]+ | 277.0859 | 277.0868 | −3.2 | 40.50 | √ | |

| 80 | Physcion | C16H12O5 | [M + H]+ | 285.0758 | 285.0767 | −3.2 | 41.37 | √ | |

| 81 | Tanshinone IIA | C19H18O3 | [M + H]+ | 295.1329 | 295.1338 | −3.0 | 42.13 | √ | |

| 82 | Alisol B,23-acetate | C32H50O5 | [M + H]+ | 515.3731 | 515.3748 | −3.3 | 43.30 | √ | |

| 83 | Emodin | C15H10O5 | [M − H]− | 269.0455 | 269.0456 | −0.4 | 45.37 | √ |

| No. | Component Name | Molecular Formula | Adducts | Expected Mass m/z | Observed | Error (ppm) | tR (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | Coclaurine + glucuronidation | C23H27NO9 | [M + H]+ | 462.1759 | 462.1758 | 0.2 | 8.56 |

| M2 | Nuciferine + didemethylation + glucuronidation | C23H25NO8 | [M + H]+ | 444.1653 | 444.1651 | 0.5 | 9.44 |

| M3 | Catechin + glucuronidation | C21H22O12 | [M − H]− | 465.1039 | 465.1038 | 0.2 | 9.74 |

| M4 | Armepavine + glucuronidation | C25H31NO9 | [M + H]+ | 490.2072 | 490.2069 | 0.6 | 10.66 |

| M5 | Nuciferine + didemethylation + glucuronidation | C23H25NO8 | [M + H]+ | 444.1653 | 444.1653 | 0.0 | 10.93 |

| M6 | Coclaurine + glucuronidation | C23H27NO9 | [M + H]+ | 462.1759 | 462.1759 | 0.0 | 10.97 |

| M7 | Nuciferine + demethylation + glucuronidation | C24H27NO8 | [M + H]+ | 458.1809 | 458.1813 | −0.9 | 11.64 |

| M8 | Puerarin + glucuronidation | C27H28O15 | [M − H]− | 591.1355 | 591.1359 | −0.7 | 12.06 |

| M9 | Coclaurine + glucuronidation | C23H27NO9 | [M + H]+ | 462.1759 | 462.1761 | −0.4 | 12.35 |

| M10 | Catechin + methylation + glucuronidation | C22H24O12 | [M − H]− | 479.1195 | 479.1190 | 1.0 | 13.01 |

| M11 | Liquiritin + glucuronidation | C27H30O15 | [M − H]− | 593.1512 | 593.1516 | −0.7 | 13.55 |

| M12 | Polydatin + glucuronidation | C26H30O14 | [M − H]− | 565.1563 | 565.1570 | −1.2 | 13.76 |

| M13 | Daidzin + sulfation | C21H20O12S | [M − H]− | 495.0603 | 495.0603 | 0.0 | 15.02 |

| M14 | Puerarin + hydroxylation + sulfation | C21H20O13S | [M − H]− | 511.0552 | 511.0554 | −0.4 | 15.05 |

| M15 | Daidzein + glucuronidation | C21H18O10 | [M − H]− | 429.0827 | 429.0827 | 0.0 | 16.59 |

| M16 | Quercetin + diglucuronidation | C27H26O19 | [M − H]− | 653.0996 | 653.1000 | −0.6 | 16.61 |

| M17 | Nuciferine + didemethylation + sulfation | C17H17NO5S | [M + H]+ | 348.0900 | 348.0901 | −0.3 | 16.64 |

| M18 | Daidzin + sulfation | C21H20O12S | [M − H]− | 495.0603 | 495.0608 | −1.0 | 17.03 |

| M19 | 3′-Methoxypuerarin + sulfation | C22H22O13S | [M − H]− | 525.0710 | 525.0715 | −1.0 | 17.05 |

| M20 | Daidzein + sulfation + glucuronidation | C21H18O13S | [M − H]− | 509.0395 | 509.0400 | −1.0 | 17.10 |

| M21 | Physcion + glucuronidation + sulfation | C22H20O14S | [M − H]− | 539.0501 | 539.0504 | −0.6 | 17.34 |

| M22 | Genistein + methylation + glucuronidation | C22H20O11 | [M − H]− | 459.0933 | 459.0934 | −0.2 | 17.58 |

| M23 | Quercetin + diglucuronidation | C27H26O19 | [M − H]− | 653.0996 | 653.0997 | −0.2 | 17.77 |

| M24 | Catechin + methylation + sulfation | C16H16O9S | [M − H]− | 383.0442 | 383.0435 | 1.8 | 18.03 |

| M25 | Liquiritigenin + glucuronidation | C21H20O10 | [M − H]− | 431.0984 | 431.0978 | 1.4 | 18.54 |

| M26 | Quercetin + diglucuronidation | C27H26O19 | [M − H]− | 653.0996 | 653.0990 | 0.9 | 18.74 |

| M27 | Liquiritigenin + glucuronidation | C21H20O10 | [M − H]− | 431.0984 | 431.0979 | 1.2 | 19.12 |

| M28 | Quercetin + diglucuronidation | C27H26O19 | [M − H]− | 653.0996 | 653.0997 | −0.2 | 19.64 |

| M29 | Nuciferine + demethylation | C18H19NO2 | [M + H]+ | 282.1489 | 282.1490 | −0.4 | 19.69 |

| M30 | Catechin + methylation + sulfation | C16H16O9S | [M − H]− | 383.0442 | 383.0438 | 1.0 | 19.77 |

| M31 | Genistein + methylation + glucuronidation | C22H20O11 | [M − H]− | 459.0933 | 459.0932 | 0.2 | 19.90 |

| M32 | Puerarin + methylation | C22H22O9 | [M − H]− | 429.1190 | 429.1188 | 0.5 | 20.21 |

| M33 | Rhein + glucuronidation | C21H16O12 | [M − H]− | 459.0569 | 459.0567 | 0.4 | 20.23 |

| M34 | Liquiritigenin + glucuronidation + sulfation | C21H20O13S | [M − H]− | 511.0552 | 511.0550 | 0.4 | 20.66 |

| M35 | Emodin + diglucuronidation | C27H26O17 | [M − H]− | 621.1097 | 621.1099 | −0.3 | 21.39 |

| M36 | Genistein + methylation + glucuronidation | C22H20O11 | [M − H]− | 459.0933 | 459.0931 | 0.4 | 21.82 |

| M37 | Daidzin + glucuronidation | C27H28O15 | [M − H]− | 591.1360 | 591.1357 | 0.5 | 21.90 |

| M38 | Emodin + sulfation + glucuronidation | C21H18O14S | [M − H]− | 525.0345 | 525.0347 | −0.4 | 22.14 |

| M39 | Rosmarinic acid + methylation + glucuronidation | C25H26O14 | [M − H]− | 549.1245 | 549.1256 | −2.0 | 22.17 |

| M40 | Morin + sulfation + glucuronidation | C21H18O16S | [M − H]− | 557.0243 | 557.0246 | −0.5 | 22.36 |

| M41 | Emodin + sulfation + glucuronidation | C21H18O14S | [M − H]− | 525.0345 | 525.0346 | −0.2 | 22.44 |

| M42 | Quercetin + methylation + glucuronidation | C22H20O13 | [M − H]− | 491.0831 | 491.0831 | 0.0 | 22.77 |

| M43 | Quercetin + methylation + glucuronidation + sulfation | C22H20O16S | [M − H]− | 571.0399 | 571.0401 | −0.4 | 23.19 |

| M44 | Emodin + diglucuronidation | C27H26O17 | [M − H]− | 621.1097 | 621.1100 | −0.5 | 23.28 |

| M45 | Rosmarinicacid + dimethylation + glucuronidation | C26H28O14 | [M − H]− | 563.1406 | 563.1406 | 0.0 | 23.48 |

| M46 | TanshinoneI + dihydroxylation + glucuronidation | C24H24O11 | [M + H]+ | 489.1391 | 489.1400 | −1.8 | 23.90 |

| M47 | Formononetin + hydroxylation | C16H12O5 | [M + H]+ | 285.0758 | 285.0761 | −1.1 | 24.23 |

| M48 | Rosmarinicacid + dimethylation + glucuronidation | C26H28O14 | [M − H]− | 563.1406 | 563.1409 | −0.5 | 24.28 |

| M49 | TanshinoneI + dihydroxylation + glucuronidation | C24H24O11 | [M + H]+ | 489.1391 | 489.1396 | −1.0 | 24.97 |

| M50 | Physcion + diglucuronidation | C28H28O17 | [M − H]− | 635.1254 | 635.1250 | 0.6 | 25.05 |

| M51 | Daidzein + hydrogenation + glucuronidation | C21H20O10 | [M − H]− | 431.0984 | 431.0982 | 0.5 | 25.49 |

| M52 | Physcion + sulfation | C16H12O8S | [M − H]− | 363.0180 | 363.0175 | 1.4 | 25.94 |

| M53 | 6-Methylrhein + glucuronidation | C22H18O12 | [M − H]− | 473.0725 | 473.0724 | 0.2 | 26.18 |

| M54 | Morin + methylation + glucuronidation | C22H20O13 | [M − H]− | 491.0831 | 491.0831 | 0.0 | 26.42 |

| M55 | Rhein + sulfation | C15H8O9S | [M − H]− | 362.9816 | 362.9814 | 0.6 | 27.15 |

| M56 | Daidzein + hydrogenation + sulfation | C15H12O7S | [M − H]− | 335.0231 | 335.0221 | 3.0 | 27.27 |

| M57 | Liquiritigenin + methylation + glucuronidation | C22H22O10 | [M − H]− | 445.1140 | 445.1127 | 2.9 | 27.41 |

| M58 | Emodin + glucuronidation | C21H18O11 | [M − H]− | 445.0776 | 445.0775 | 0.2 | 27.73 |

| M59 | Daidzein + disulfation | C15H10O10S2 | [M − H]− | 412.9643 | 412.9639 | 1.0 | 27.93 |

| M60 | Lithospermic acid + dimethylation | C29H26O12 | [M − H]− | 565.1352 | 565.1357 | −0.9 | 28.29 |

| M61 | Cryptotanshinone + trihydroxylation | C19H20O6 | [M + H]+ | 345.1333 | 345.1339 | −1.7 | 28.59 |

| M62 | Quercetin + dimethylation + glucuronidation | C23H22O13 | [M − H]− | 505.0988 | 505.0990 | −0.4 | 28.65 |

| M63 | Lithospermic acid + dimethylation | C29H26O12 | [M − H]− | 565.1352 | 565.1355 | −0.5 | 28.68 |

| M64 | Quercetin + dimethylation + glucuronidation | C23H22O13 | [M − H]− | 505.0988 | 505.0991 | −0.6 | 29.36 |

| M65 | Cryptotanshinone + Hydroxylation | C19H20O4 | [M + H]+ | 313.1434 | 313.1439 | −1.6 | 29.80 |

| M66 | Physcion + glucuronidation | C22H20O11 | [M − H]− | 459.0933 | 459.0937 | −0.9 | 30.09 |

| M67 | Emodin + glucuronidation | C21H18O11 | [M − H]− | 445.0776 | 445.0778 | −0.4 | 30.36 |

| M68 | Rosmarinic acid + dimethylation + sulfation | C20H20O11S | [M − H]− | 467.0654 | 467.0636 | 3.9 | 30.60 |

| M69 | Physcion + glucuronidation | C22H20O11 | [M − H]− | 459.0933 | 459.0934 | −0.2 | 30.64 |

| M70 | Tanshinone I + hydroxylation | C18H12O4 | [M + H]+ | 293.0808 | 293.0817 | −3.1 | 32.25 |

| M71 | Daidzein + hydrogenation + sulfation | C15H12O7S | [M − H]− | 335.0231 | 335.0230 | 0.3 | 34.89 |

| M72 | Tanshinone IIA + hydrogenation | C19H20O3 | [M + H]+ | 297.1485 | 297.1491 | −2.0 | 36.81 |

| M73 | Cryptotanshinone + hydroxylation + hydrogenation | C19H22O4 | [M + H]+ | 315.1591 | 315.1599 | −2.5 | 38.49 |

| M74 | Emodin + sulfation | C15H10O8S | [M − H]− | 349.0024 | 349.0021 | 0.9 | 44.39 |

| M75 | Emodin + sulfation | C15H10O8S | [M − H]− | 349.0024 | 349.0022 | 0.6 | 44.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, T.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guan, Z.; Liu, T.; Qin, D.; Xu, J. A Multi-Omics Study Reveals the Active Components and Therapeutic Mechanism of Erhuang Quzhi Formula for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3849. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243849

Ma T, Li M, Liu Y, Chen Y, Guan Z, Liu T, Qin D, Xu J. A Multi-Omics Study Reveals the Active Components and Therapeutic Mechanism of Erhuang Quzhi Formula for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3849. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243849

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Teng, Mingzhu Li, Yuan Liu, Yu Chen, Zipeng Guan, Tonghua Liu, Dongmei Qin, and Jia Xu. 2025. "A Multi-Omics Study Reveals the Active Components and Therapeutic Mechanism of Erhuang Quzhi Formula for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3849. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243849

APA StyleMa, T., Li, M., Liu, Y., Chen, Y., Guan, Z., Liu, T., Qin, D., & Xu, J. (2025). A Multi-Omics Study Reveals the Active Components and Therapeutic Mechanism of Erhuang Quzhi Formula for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients, 17(24), 3849. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243849