Analysis of Determinants of Dietary Iodine Intake of Adolescents from Northern Regions of Poland: Coastal Areas and Lake Districts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Aspects

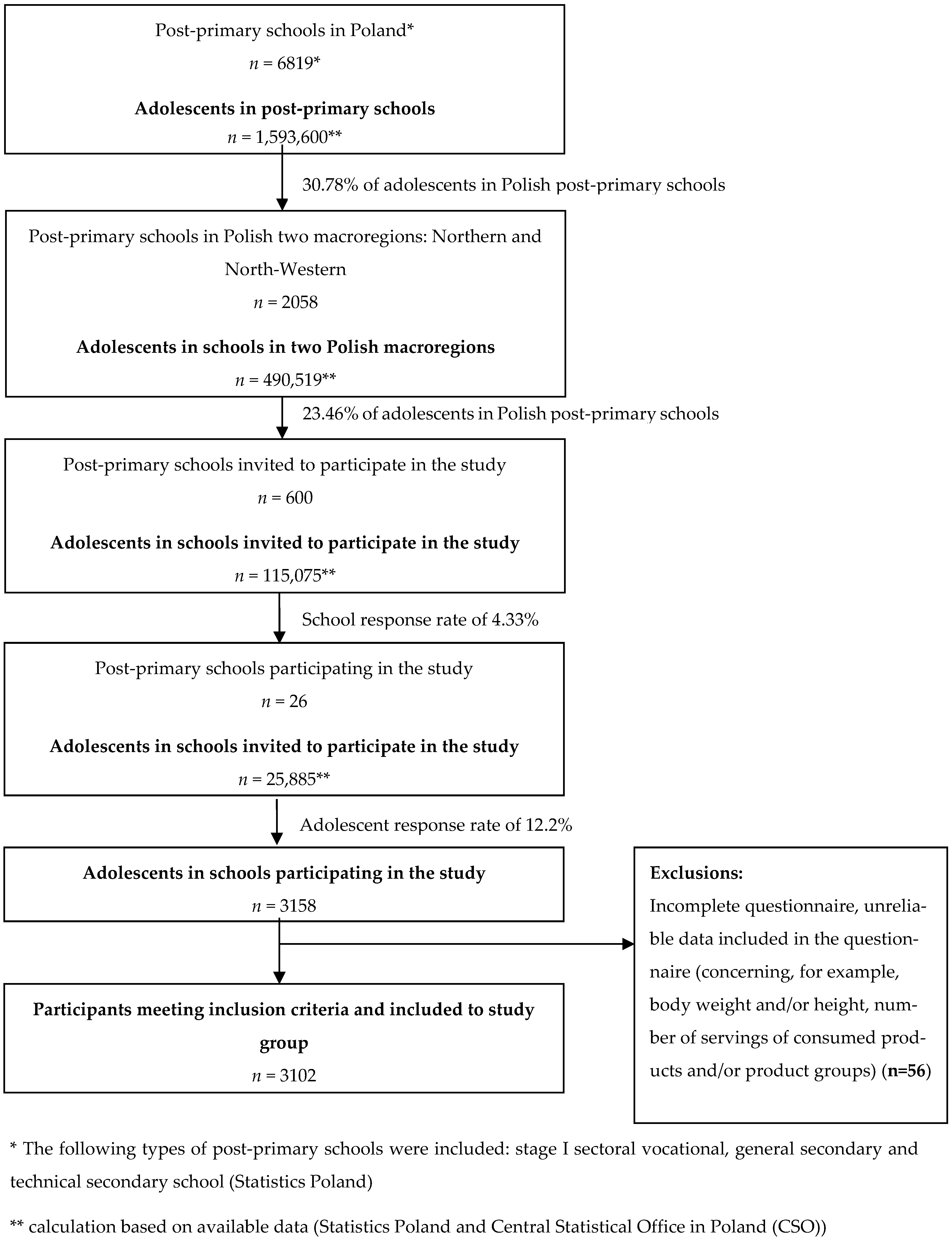

2.2. Research Design

2.3. Study Participants

- -

- students had to be enrolled in a school whose principal had agreed to participate in the study,

- -

- age from 14 to 20 years (normal age for this level of education in Poland),

- -

- informed consent from participants and their parents or legal guardians to participate in the study.

- -

- pregnancy and/or lactation in the case of female students,

- -

- incomplete questionnaire and unreliable data contained in the questionnaire (e.g., regarding number of servings of consumed foods and/or food groups, body height, weight). Both authors independently reviewed and verified the completeness and reliability of the data entered by the study participants in each questionnaire. Questionnaires that were incomplete and/or contained unreliable data were excluded from further analysis.

2.4. Questionnaire

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- (1)

- The macroregion in which the school attended by the study participants was located, defined based on the macroregion categories adopted by the Central Statistical Office: North-Western and North [24];

- (2)

- Location of the school attended by study participants: countryside, small city (under 20,000 inhabitants), medium city (between 20,000 and 100,000 inhabitants), and big city (over 100,000 inhabitants);

- (3)

- Age: minors (from 14 to 17 years) and young adults (from 18 to 20 years);

- (4)

- BMI categories: underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity–for adults, standard WHO cut-off values were used: below 18.5 kg/m2 for underweight, from 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2 for normal weight, from 25 to 29.9 kg/m2 for overweight, and above 30 kg/m2 for obesity [41]. For minors, Polish height cut-off values were used [39]: below the 5th percentile for underweight, from the 5th to 85th percentile for normal weight, from the 85th to 95th percentile for overweight, and above the 95th percentile for obesity;

- (5)

- Declaration of taking iodine-containing supplements and/or medications: “no” or “yes”;

- (6)

- Dietary sources of iodine: (a) fish and fish products (GR1: carp, eel, perch, pike, trout (rainbow and brown), sardine, sole, herring, flounder, salmon, mackerel, tuna, halibut, plaice, pollock, cod; GR2: smoked eel and other smoked fish (mackerel, salmon, herring); GR3: canned fish products (sprats and sardines in tomatoes and in oil, marinated herring and tuna) and herring in cream); as well as other food groups (b) dairy products; (c) eggs; (d) meat and meat products; (e) cereal products; (f) vegetables, legumes, potatoes and fruits; (g) nuts and seeds; (h) beverages; (i) salt; (j) others (fats, gelatin and chocolate).

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Participants

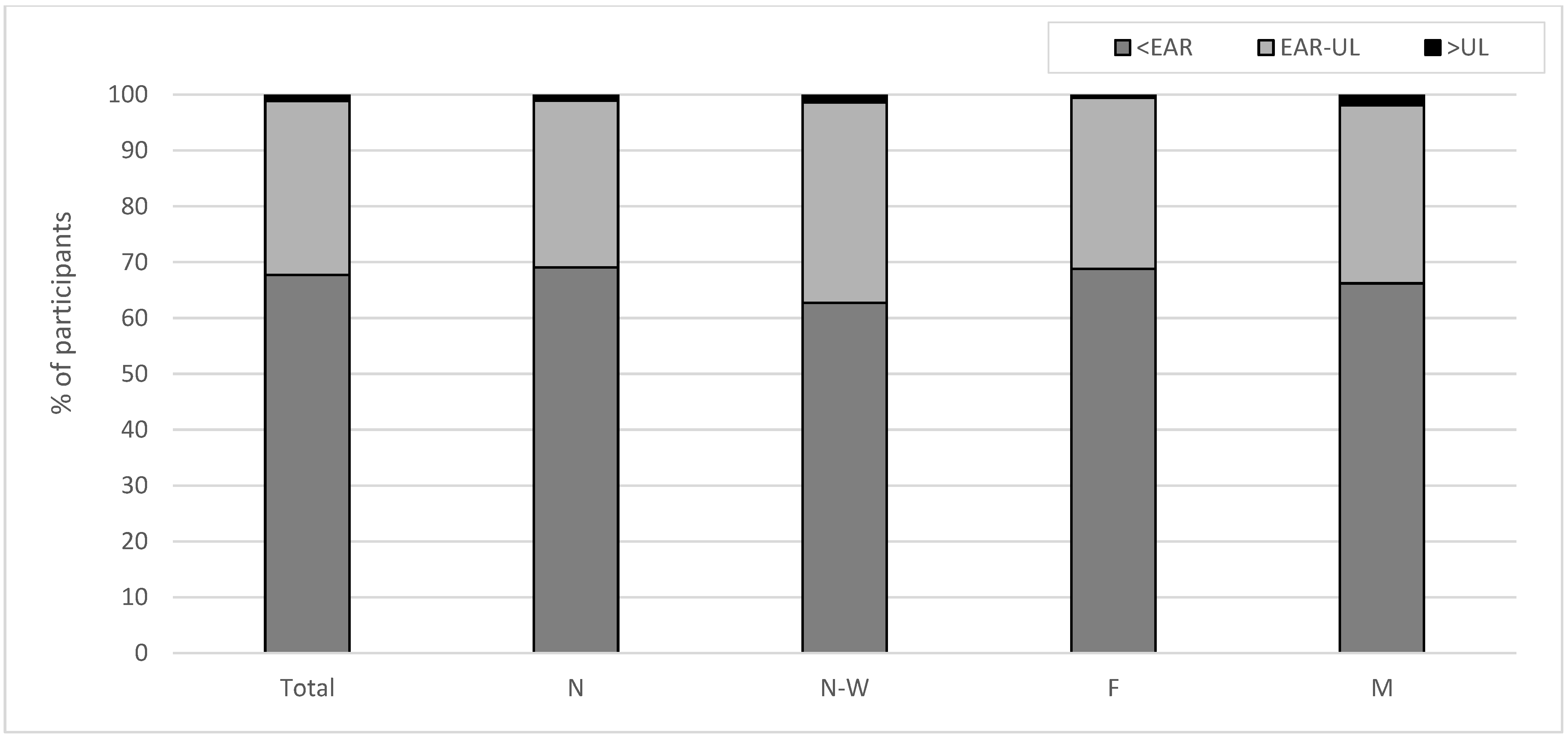

3.2. Habitual dIi and Sources of Iodine

3.3. Determinants of dIi

3.4. Correlations

4. Discussion

4.1. The Study’s Strengths and Weaknesses

4.2. Practical Applications and Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| dIi | dietary iodine intake, intake of iodine from dietary sources |

| EAR | estimated average requirement |

| IDDs | iodine deficiency disorders |

| GR1 | carp, eel, perch, trout, pike, sardine, sole, herring, flounder, salmon, mackerel, tuna, halibut, plaice, pollock, cod |

| GR2 | smoked fishes |

| GR3 | herring in a creamy sauce, pickled herring and fish products in tins |

| RDA | recommended dietary allowance |

| UL | tolerable upper intake level |

References

- Sorrenti, S.; Baldini, E.; Pironi, D.; Lauro, A.; D’Orazi, V.; Tartaglia, F.; Tripodi, D.; Lori, E.; Gagliardi, F.; Praticò, M.; et al. Iodine: Its Role in Thyroid Hormone Biosynthesis and Beyond. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiljev, V.; Subotić, A.; Marinović Glavić, M.; Juraga, D.; Bilajac, L.; Jelaković, B.; Rukavina, T. Overview of Iodine Intake. Southeast. Eur. Med. J. 2022, 6, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisco, G.; De Tullio, A.; Triggiani, D.; Zupo, R.; Giagulli, V.A.; De Pergola, G.; Piazzolla, G.; Guastamacchia, E.; Sabbà, C.; Triggiani, V. Iodine Deficiency and Iodine Prophylaxis: An Overview and Update. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krela-Kaźmierczak, I.; Czarnywojtek, A.; Skoracka, K.; Rychter, A.M.; Ratajczak, A.E.; Szymczak-Tomczak, A.; Ruchała, M.; Dobrowolska, A. Is There an Ideal Diet to Protect against Iodine Deficiency? Nutrients 2021, 13, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch-McChesney, A.; Lieberman, H.R. Iodine and Iodine Deficiency: A Comprehensive Review of a Re-Emerging Issue. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinka, Z.; Gmitrzuk, J.; Wiśniewska, K.; Jachymek, A.; Opatowska, M.; Jakubiec, J.; Kucharski, T.; Piotrowska, M. The role of iodine in thyroid function and iodine impact on the course of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis—Review. Qual. Sport. 2024, 16, 52639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.Y.; Inoue, K.; Rhee, C.M.; Leung, A.M. Risks of Iodine Excess. Endocr. Rev. 2024, 45, 858–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shang, F.; Liu, C.; Zhai, X. The correlation between iodine and metabolism: A review. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1346452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Prevention and Control of Iodine Deficiency in the WHO European Region: Adapting to Changes in Diet and Lifestyle; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289061193 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Møllehave, L.T.; Eliasen, M.H.; Strēle, I.; Linneberg, A.; Moreno-Reyes, R.; Ivanova, L.B.; Kusić, Z.; Erlund, I.; Ittermann, T.; Nagy, E.V.; et al. Register-based information on thyroid diseases in Europe: Lessons and results from the EUthyroid collaboration. Endocr. Connect. 2022, 11, e210525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan Öksüz, S.B.; Erdoğan, M.F. Current iodine status in Europe and Türkiye in the light of the World Health Organization European region 2024 report: Are we losing our achievements? Endocrinol. Res. Pract. 2025, 29, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygmunt, A.; Adamczewski, Z.; Wojciechowska-Durczynska, K.; Krawczyk-Rusiecka, K.; Bieniek, E.; Stasiak, M.; Zygmunt, A.; Purgat, K.; Zakrzewski, R.; Brzezinski, J.; et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of iodine prophylaxis in Poland based on over 20 years of observations of iodine supply in school-aged children in the central region of the country. Arch. Med. Sci. 2019, 15, 1468–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trofimiuk-Müldner, M.; Konopka, J.; Sokołowski, G.; Dubiel, A.; Kieć-Klimczak, M.; Kluczyński, Ł.; Motyka, M.; Rzepka, E.; Walczyk, J.; Sokołowska, M.; et al. Current iodine nutrition status in Poland (2017): Is the Polish model of obligatory iodine prophylaxis able to eliminate iodine deficiency in the population? Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 2467–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeliga, K.; Antosz, A.; Skrzynska, K.; Kalina-Faska, B.; Gawlik, A. Subclinical hypothyroidism in children and adolescents as mild dysfunction of the thyroid gland: A single-center study. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2023, 29, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W. The burden of iodine deficiency. Arch. Med. Sci. 2024, 20, 1484–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojković, M.V. Thyroid function disorders. Arh. Farm. 2022, 72, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Poland. Healthcare in Households in 2023. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/zdrowie/zdrowie/ochrona-zdrowia-w-gospodarstwach-domowych-w-2023-r-,2,8.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Statistics Poland. Health Status of Population in Poland in 2019. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/zdrowie/zdrowie/stan-zdrowia-ludnosci-polski-w-2019-r-,26,1.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Szybiński, Z. Iodine Prophylaxis in the Lights of the Last Recommendation of WHO on Reduction of Daily Salt Intake. Recent Pat. Endocr. Metab. Immune Drug Discov. 2017, 11, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nista, F.; Bagnasco, M.; Gatto, F.; Albertelli, M.; Vera, L.; Boschetti, M.; Musso, N.; Ferone, D. The effect of sodium restriction on iodine prophylaxis: A review. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2022, 45, 1121–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska, B.; Malczewska-Lenczowska, J.; Wajszczyk, B. Evaluation of dietary intake of vitamins and minerals in 13–15-years-old boys from a sport school in Warsaw. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2016, 67, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dobrowolski, H.; Włodarek, D. Dietary Intake of Polish Female Soccer Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Register of Schools and Educational Institutions in Poland. Available online: https://rspo.gov.pl/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Statistics Poland. The NUTS Classification in Poland. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/regional-statistics/classificationofterritorial-units/classification-of-territorial-units-for-statistics-nuts/the-nuts-classification-in-poland/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Lachowicz, K.; Stachoń, M. Determinants of Dietary Vitamin D Intake in Population-Based Cohort Sample of Polish Female Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utri-Khodadady, Z.; Skolmowska, D.; Głąbska, D. Determinants of Fish Intake and Complying with Fish Consumption Recommendations—A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study Among Secondary School Students in Poland. Nutrients 2024, 16, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachoń, M.; Lachowicz, K. Assessment of Determinants of Dietary Vitamin D Intake in a Polish National Sample of Male Adolescents. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAWI Methodology—Computer Assisted Web Interview. Available online: https://www.idsurvey.com/en/cawi-methodology/ (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Głąbska, D.; Malowaniec, E.; Guzek, D. Validity and Reproducibility of the Iodine Dietary Intake Questionnaire Assessment Conducted for Young Polish Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health (NCI/NIH). Register of NCI-Developed Short Diet Assessment Instruments. Available online: https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/diet/shortreg/instruments/ (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Kunachowicz, H.; Nadolna, I.; Przygoda, B.; Iwanow, K. Tables of Composition and Nutritional Value of Food; PZWL: Warsaw, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Szponar, L.; Wolnicka, K.; Rychlik, E. Atlas of Portion Sizes of Food Products and Dishes; IŻŻ: Warsaw, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rychlik, E.; Stoś, K.; Woźniak, A.; Mojska, H. (Eds.) Nutrition Recommendations for the Population of Poland; Polish National Food and Nutrition Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2024; ISBN 978-83-65870-78-0. [Google Scholar]

- Stimec, M.; Mis, N.F.; Smole, K.; Sirca-Campa, A.; Kotnik, P.; Zupancic, M.; Battelino, T.; Krizisnik, C. Iodine intake of Slovenian adolescents. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2007, 51, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsdóttir, I.; Brantsæter, A.L. Iodine: A scoping review for Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 67, 10369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkaik-Kloosterman, J.; Buurma-Rethans, E.J.M.; Dekkers, A.L.M.; van Rossum, C.T.M. Decreased, but still sufficient, iodine intake of children and adults in the Netherlands. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 1020–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychlik, E. Salt—What You Need to Know About It. Available online: https://ncez.pzh.gov.pl/abc-zywienia/sol-co-trzeba-o-niej-wiedziec/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Sodium Reduction. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sodium-reduction (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- OLAF Calculator from OLAF Study. Available online: https://nauka.czd.pl/kalkulator-2/ (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Kulaga, Z.; Litwin, M.; Tkaczyk, M.; Różdżyńska, A.; Barwicka, K.; Grajda, A.; Świąder, A.; Gurzkowska, B.; Napieralska, E.; Pan, H. The Height-, Weight-, and BMI-for-Age of Polish School-Aged Children and Adolescents Relative to International and Local Growth References. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Healthy Lifestyle—WHO Recommendations. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/a-healthy-lifestyle---who-recommendations (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Bath, S.C.; Verkaik-Kloosterman, J.; Sabatier, M.; Ter Borg, S.; Eilander, A.; Hora, K.; Aksoy, B.; Hristozova, N.; van Lieshout, L.; Tanju Besler, H.; et al. A systematic review of iodine intake in children, adults, and pregnant women in Europe-comparison against dietary recommendations and evaluation of dietary iodine sources. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 2154–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stimec, M.; Kobe, H.; Smole, K.; Kotnik, P.; Sirca-Campa, A.; Zupancic, M.; Battelino, T.; Krzisnik, C.; Fidler Mis, N. Adequate iodine intake of Slovenian adolescents is primarily attributed to excessive salt intake. Nutr. Res. 2009, 29, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Outzen, M.; Lund, C.E.; Christensen, T.; Trolle, E.; Ravn-Haren, G. Assessment of iodine fortification of salt in the Danish population. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 2939–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groufh-Jacobsen, S.; Larsson, C.; Margerison, C.; Mulkerrins, I.; Aune, D.; Medin, A.C. Micronutrient intake and status in young vegans, lacto-ovo-vegetarians, pescatarians, flexitarians, and omnivores. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 2725–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulkerrins, I.; Medin, A.C.; Groufh-Jacobsen, S.; Margerison, C.; Larsson, C. Micronutrient intake and nutritional status in 16-to-24-year-olds adhering to vegan, lacto-ovo-vegetarian, pescatarian or omnivorous diets in Sweden. Eur. J. Nutr. 2025, 64, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung. Declining iodine intake in the population: Model scenarios to improve iodine intake in children and adolescents. In BfR-Stellungnahmen; BfR Opinion No. 026/2022 Issued 17 October 2022; German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment: Berlin, Germany, 2022; Volume 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sobaler, A.M.; Aparicio, A.; González-Rodríguez, L.G.; Cuadrado-Soto, E.; Rubio, J.; Marcos, V.; Sanchidrián, R.; Santos, S.; Pérez-Farinós, N.; Dal Re, M.Á.; et al. Adequacy of Usual Vitamin and Mineral Intake in Spanish Children and Adolescents: ENALIA Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, E.; Buffini, M.; Heslin, A.M.; Nugent, A.P.; Kehoe, L.; Walton, J.; Kearney, J.; Flynn, A.; McNulty, B. Iodine intake and status of school-age girls in Ireland. Eur. J. Nutr. 2025, 64, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacone, R.; Iaccarino Idelson, P.; Campanozzi, A.; Rutigliano, I.; Russo, O.; Formisano, P.; Galeone, D.; Macchia, P.E.; Strazzullo, P. MINISAL-GIRCSI Study Group. Relationship between salt consumption and iodine intake in a pediatric population. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2193–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malczyk, E.; Muc-Wierzgoń, M.; Fatyga, E.; Dzięgielewska-Gęsiak, S. Salt Intake of Children and Adolescents: Influence of Socio-Environmental Factors and School Education. Nutrients 2024, 16, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagag, S.; Habib, E.; Tawfik, S. Assessment of Knowledge and Practices toward Salt Intake among Adolescents. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, K.; Brodowski, J.; Pokorska-Niewiada, K.; Szczuko, M. The Change in the Content of Nutrients in Diets Eliminating Products of Animal Origin in Comparison to a Regular Diet from the Area of Middle-Eastern Europe. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EUthyroid Consortium. The Krakow Declaration on Iodine: Tasks and Responsibilities for Prevention Programs Targeting Iodine Deficiency Disorders. Eur. Thyroid J. 2018, 7, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euthyroid. Towards the Elimination of Iodine Deficiency and Preventable Thyroid-Related Diseases in Europe. Available online: https://euthyroid.eu/factsheets/EUthyroid_factsheet_GB.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Statistics Poland. Average Monthly Consumption of Selected Food Products per Person. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl/metadane/cechy/2456 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Kochanowicz, Z.; Bórawski, P.; Czaplicka, J. Regional diversification of milk production in Poland—An attempt to identify the condition and causes. Probl. Econ. Law 2018, 1, 1–11. Available online: https://publisherspanel.com/api/files/view/658997.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Karaczun, Z.M.; Walczak, J. The Situation of Dairy Farming in Poland in the Context of Current Health and Environmental Challenges; Association of Polish Dairy Processors: Warsaw, Poland, 2023. Available online: https://www.portalmleczarski.pl/nasze-raporty/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Statistics Poland; Socio-Economic Situation of Voivodships No. 4/2022. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/inne-opracowania/informacje-o-sytuacji-spoleczno-gospodarczej/sytuacja-spoleczno-gospodarcza-wojewodztw-nr-42022,3,48.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Fraszka-Sobczyk, E.; Palma, A. Taxonomic analysis of the differences among Polish voivodships in terms of economic development. Pol. Stat. 2025, 70, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, H.Y.; Can, M.F. Factors affecting the individual consumption level of milk and dairy products. Semin. Ciênc. Agrár. 2022, 43, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawska, A. Factors influencing the consumption of dairy products in Polish households. Sci. J. Wars. Univ. Life Sci. Econ. Organ. Food Econ. 2017, 120, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myszkowska-Ryciak, J.; Harton, A.; Lange, E.; Laskowski, W.; Gajewska, D. Nutritional Behaviors of Polish Adolescents: Results of the Wise Nutrition—Healthy Generation Project. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.G.; Kazemi, A.; Kelishadi, R.; Mostafavi, F. A Review on Determinants of Nutritional Behavior in Teenagers. Iran. J. Pediatr. 2017, 27, e6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, A.N.; O’Sullivan, E.J.; Kearney, J.M. Considerations for health and food choice in adolescents. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Poland. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland 2024. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/download/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5515/2/24/1/rocznik_statystyczny_rzeczypospolitej_polskiej_2024_3.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Hryszko, K. Consumption of fish, seafood, and processed products. In Fish Market: Current Situation and Prospects; Hryszko, K., Ed.; Nr 35. Market Analyses; Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics—National Research Institute Press: Wroclaw, Poland, 2024; pp. 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kosicka-Gębska, M.; Ładecka, Z. Conditions and trends of fish consumption in Poland. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2012, 14, 238–244. [Google Scholar]

- Utri-Khodadady, Z.; Głąbska, D. Analysis of Fish-Consumption Benefits and Safety Knowledge in a Population-Based Sample of Polish Adolescents. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govzman, S.; Looby, S.; Wang, X.; Butler, F.; Gibney, E.R.; Timon, C.M. A systematic review of the determinants of seafood consumption. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 126, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, M.F.; Günlü, A.; Can, H.Y. Fish consumption preferences and factors influencing it. Food Science and Technology Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 35, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frąckiewicz, J.; Sawejko, Z.; Ciecierska, A.; Drywień, M.E. Gender as a factor influencing the frequency of meat and fish consumption in young adults. Rocz. Państw. Zakł. Hig. 2023, 74, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokarczyk, G.; Bienkiewicz, G.; Krzywiński, T. Polish carp innovatively. In Improving the Quality of Guide Services During the Pandemic; Lesiów, T., Ed.; Wroclaw University of Economics and Business Press: Wroclaw, Poland, 2023; pp. 60–85. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Poland. Statistical Yearbook of the Regions—Poland 2024. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/download/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5515/4/19/1/rocznik_statystyczny_wojewodztw_2024.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

| Variable | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 3102 | 100 | ||

| Macroregion of northern Poland | Northern | 2418 | 77.95 | |

| North-Western | 684 | 22.05 | ||

| Location of the school | Countryside | Total | 342 | 11.02 |

| Northern | 240 | 7.74 | ||

| North-Western | 102 | 3.29 | ||

| Small city (<20,000) | Total | 644 | 20.76 | |

| Northern | 488 | 14.44 | ||

| North-Western | 196 | 6.32 | ||

| Medium city (20,000–100,000) | Total | 2022 | 65.18 | |

| Northern | 1709 | 55.09 | ||

| North-Western | 313 | 10.09 | ||

| Big city (>100,000) | Total | 94 | 3.04 | |

| Northern | 21 | 0.68 | ||

| North-Western | 73 | 2.35 | ||

| Sex | Female | 1751 | 56.45 | |

| Male | 1351 | 43.55 | ||

| Age | 14–17 years old | 2195 | 70.76 | |

| 18–20 years old | 907 | 29.24 | ||

| Body Mass Index (BMI) classification | Underweight | All | 156 | 5.03 |

| Female | 115 | 3.71 | ||

| Male | 41 | 1.32 | ||

| 14–17 years old | 89 | 2.87 | ||

| 18–20 years old | 67 | 2.17 | ||

| Normal weight | All | 2178 | 70.21 | |

| Female | 1251 | 40.33 | ||

| Male | 927 | 29.88 | ||

| 14–17 years old | 1565 | 50.45 | ||

| 18–20 years old | 613 | 19.76 | ||

| Overweight | All | 465 | 14.99 | |

| Female | 236 | 7.61 | ||

| Male | 229 | 7.38 | ||

| 14–17 years old | 316 | 10.19 | ||

| 18–20 years old | 149 | 4.80 | ||

| Obesity | All | 303 | 9.77 | |

| Female | 149 | 4.80 | ||

| Male | 154 | 4.97 | ||

| 14–17 years old | 225 | 7.25 | ||

| 18–20 years old | 78 | 2.51 | ||

| Iodine supplementation | Yes | 164 | 5.29 | |

| No | 2938 | 94.71 | ||

| Iodine Source | Dietary Iodine Intake in µg Per Day | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± Standard Deviation | Median (Min–Max) * | ||

| Total from all food sources 1 | 95.88 ± 105.36 | 66.83 (0.30–1176.21) | |

| Total from natural sources | 72.35 ± 84.63 | 53.00 (0.30–169.79) | |

| Dairy products | 21.91 ± 23.61 | 15.02 (0.00–283.20) | |

| Eggs | 2.75 ± 3.27 | 2.01 (0.00–26.86) | |

| Meat and meat products | 3.04 ± 2.97 | 2.24 (0.00–22.43) | |

| Fish and fish products | Total | 5.77 ± 9.61 | 2.38 (0.00–95.42) |

| GR1 | 4.24 ± 7.74 | 1.62 (0.00–81.79) | |

| GR2 | 1.02 ± 2.36 | 0.00 (0.00–33.30) | |

| GR3 | 0.48 ± 1.18 | 0.00 (0.00–16.97) | |

| Cereals | 2.95 ± 2.90 | 2.10 (0.00–26.88) | |

| Vegetables, legumes, potatoes and fruits | 11.12 ± 11.98 | 7.95 (0.00–155.90) | |

| Nuts and seeds | 4.70 ± 7.63 | 2.73 (0.00–69.39) | |

| Beverages | 19.39 ± 68.47 | 5.64 (0.00–807.10) | |

| Iodine-fortified salt | 23.53 ± 49.74 | 0.00 (0.00–556.60) | |

| Other # | 0.72 ± 1.02 | 0.45 (0.00–12.71) | |

| Iodine Intake Determinants | Iodine Intake (µg/d) | p Value ** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± Standard Deviation | Median (Min–Max) * | |||

| Macroregions of northern Poland | N (n = 2418) | 92.54 ± 100.98 | 65.63 (0.30–1176.20) | <0.001 (1) |

| N-W (n = 684) | 107.72 ± 118.91 | 74.20 (0.41–985.30) | ||

| Location of the school | C-S (n = 342) | 98.36 ± 123.95 | 64.68 (0.41–1033.06) | 0.80 (2) |

| Sc (n = 644) | 97.77 ± 103.96 | 69.15 (0.30–985.300) | ||

| Mc (n = 2022) | 94.47 ± 102.07 | 66.80 (0.41–1176.20) | ||

| Bc (n = 94) | 104.53 ± 111.91 | 70.71 (10.72–761.87) | ||

| Sex | Female (n = 1751) | 94.30 ± 107.85 | 66.44 (0.30–1176.20) | 0.10 (1) |

| Male (n = 1351) | 97.94 ± 102.06 | 68.05 (0.41–981.40) | ||

| Age (years) | 14–17 (n = 2195) | 96.63 ± 107.62 | 66.83 (0.30–1176.20) | 0.80 (1) |

| 18–20 (n = 907) | 94.08 ± 99.73 | 67.18 (0.41–881.45) | ||

| Body Mass Index classification | Uw (n = 156) | 92.06 ± 85.01 | 68.30 (0.30–538.50) | 0.76 (2) |

| Nw (n = 2178) | 97.06 ± 107.51 | 67.42 (0.41–1176.20) | ||

| Ow (n = 465) | 93.41 ± 101.01 | 66.78 (0.41–985.30) | ||

| Ob (n = 303) | 93.22 ± 106.07 | 63.00 (9.20–1102.40) | ||

| Iodine supplementation | Yes (n = 164) | 103.62 ± 138.33 | 67.56 (0.71–1176.20) | 0.90 (1) |

| No (n = 2938) | 95.46 ± 103.23 | 66.83 (0.30–1102.40) | ||

| Variable | Correlations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| R * | p | ||

| Iodine intake from different group products (µg/day) vs. total iodine intake (µg/day) | Dairy products | 0.61 | <0.001 |

| Eggs | 0.37 | <0.001 | |

| Meat and meat products | 0.39 | <0.001 | |

| Fish and fish products | 0.15 | <0.001 | |

| Cereals | 0.48 | <0.001 | |

| Vegetables, legumes, potatoes and fruits | 0.54 | <0.001 | |

| Nuts and seeds | 0.41 | <0.001 | |

| Beverages | 0.51 | <0.001 | |

| Iodine-fortified salt | 0.63 | <0.001 | |

| Other # | 0.42 | <0.001 | |

| Iodine-fortified salt intake (g/day) vs. total iodine intake (µg/day) | 0.63 | <0.001 | |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) vs. total iodine intake (µg/day) | −0.02 | 0.28 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lachowicz, K.; Stachoń, M. Analysis of Determinants of Dietary Iodine Intake of Adolescents from Northern Regions of Poland: Coastal Areas and Lake Districts. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3813. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243813

Lachowicz K, Stachoń M. Analysis of Determinants of Dietary Iodine Intake of Adolescents from Northern Regions of Poland: Coastal Areas and Lake Districts. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3813. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243813

Chicago/Turabian StyleLachowicz, Katarzyna, and Małgorzata Stachoń. 2025. "Analysis of Determinants of Dietary Iodine Intake of Adolescents from Northern Regions of Poland: Coastal Areas and Lake Districts" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3813. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243813

APA StyleLachowicz, K., & Stachoń, M. (2025). Analysis of Determinants of Dietary Iodine Intake of Adolescents from Northern Regions of Poland: Coastal Areas and Lake Districts. Nutrients, 17(24), 3813. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243813