The Association of Dietary Diabetes Risk Reduction Score and the Risk of Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Literature Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- [P] Population: Adults aged ≥18 years without baseline cancer.

- [E] Exposure: Dietary diabetes risk reduction score (DDRRS).

- [C] Comparison: The highest vs. the lowest DDRRS.

- [O] Outcomes: Estimated cancer risk (all cancers, e.g., colorectal, breast, liver, etc.).

- [S] Study design: Observational studies, including case–control and cohort studies.

2.3. Data Screening and Extraction

2.4. Assessment of Study Quality

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

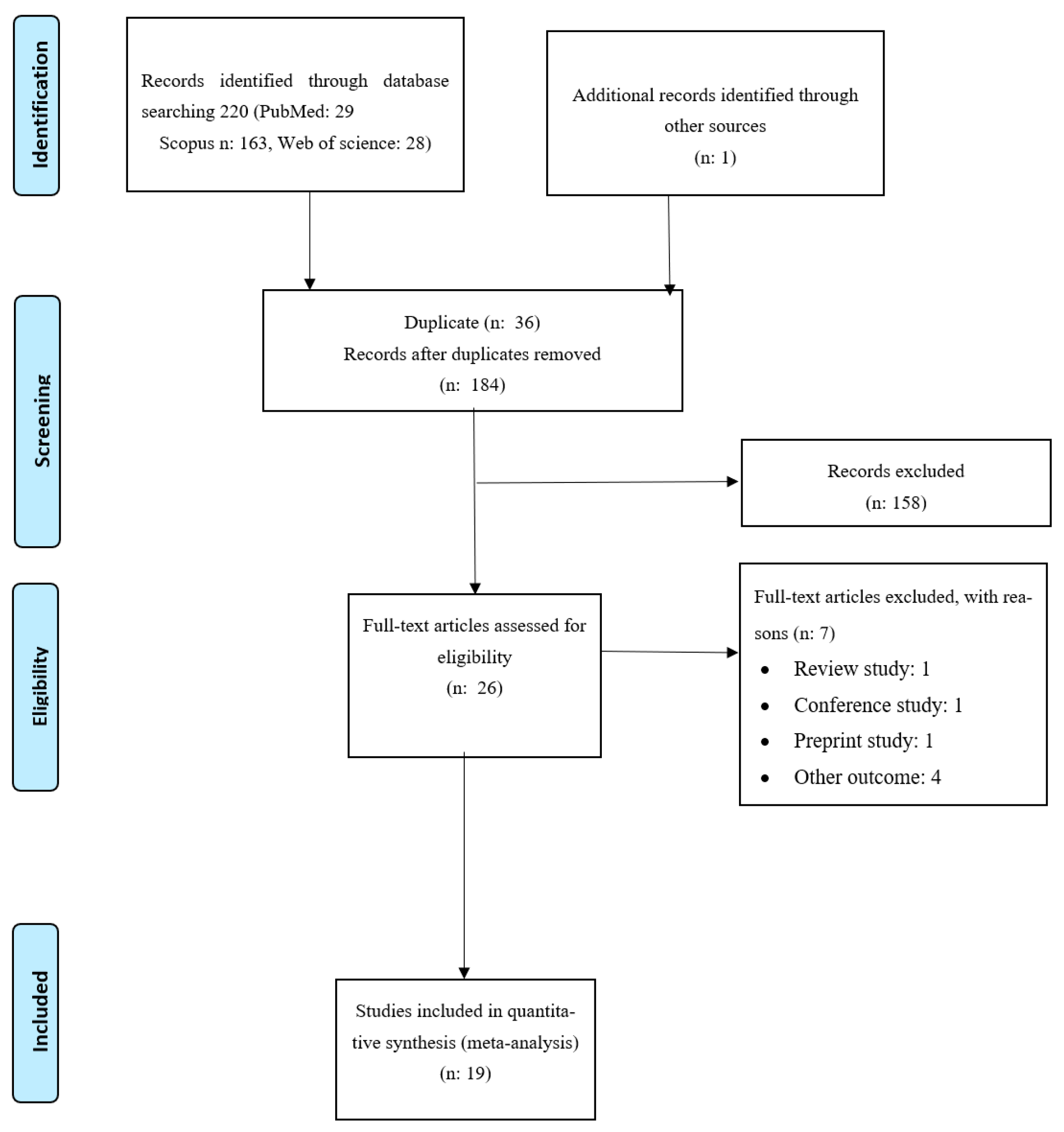

3.1. Studies Selection

3.2. Description of Eligible Studies

3.3. Meta-Analysis

Overall Analysis

3.4. Subgroup Analysis

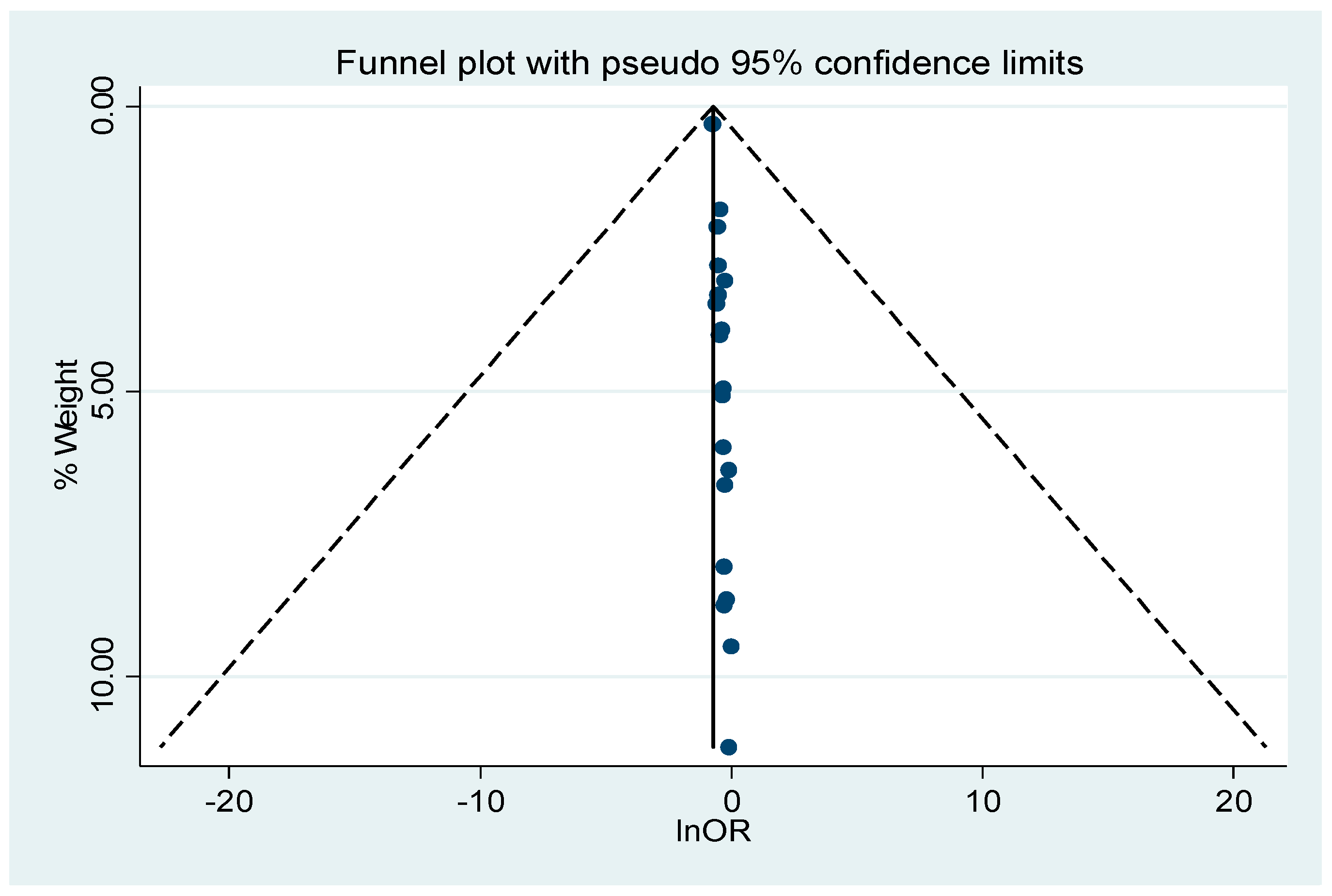

3.5. Publication Bias and Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, J.S.; Amend, S.R.; Austin, R.H.; Gatenby, R.A.; Hammarlund, E.U.; Pienta, K.J. Updating the definition of cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2023, 21, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Cancer. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Chen, S.; Cao, Z.; Prettner, K.; Kuhn, M.; Yang, J.; Jiao, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Geldsetzer, P.; Bärnighausen, T. Estimates and projections of the global economic cost of 29 cancers in 204 countries and territories from 2020 to 2050. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Hu, F.B. The global implications of diabetes and cancer. Lancet 2014, 383, 1947–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Screening, P.; Board, P.E. Cancer Prevention Overview (PDQ®). In PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]; National Cancer Institute (US): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Han, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Rimm, E.B.; Hu, F.B.; Sun, Q. Associations between plant-based dietary patterns and risks of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mortality—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. J. 2023, 22, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, X.; Coday, M.; Garcia, D.O.; Li, X.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Naughton, M.J.; Lopez-Pentecost, M.; Saquib, N.; Shadyab, A.H. Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages and risk of liver cancer and chronic liver disease mortality. JAMA 2023, 330, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; Giovannucci, E.; Boffetta, P.; Fadnes, L.T.; Keum, N.; Norat, T.; Greenwood, D.C.; Riboli, E.; Vatten, L.J.; Tonstad, S. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality—A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1029–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Di Bella, G.; Veronese, N.; Barbagallo, M. Impact of Mediterranean diet on chronic non-communicable diseases and longevity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerikanou, C.; Tzavara, C.; Kaliora, A.C. Dietary Patterns and Nutritional Value in Non-Communicable Diseases. Nutrients 2024, 16, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, J.J.; Mattei, J.; Hughes, M.D.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C. Dietary Diabetes Risk Reduction Score, Race and Ethnicity, and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in Women. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfiore, A.; Malaguarnera, R. Insulin receptor and cancer. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2011, 18, R125–R147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracz, A.F.; Szczylik, C.; Porta, C.; Czarnecka, A.M. Insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling in renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turati, F.; Rossi, M.; Mattioli, V.; Bravi, F.; Negri, E.; La Vecchia, C. Diabetes risk reduction diet and the risk of pancreatic cancer. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, L.; Jung, S.Y.; Pichardo, M.S.; Lopez-Pentecost, M.; Rohan, T.E.; Saquib, N.; Sun, Y.; Tabung, F.K.; Zheng, T.; et al. Diabetes risk reduction diet and risk of liver cancer and chronic liver disease mortality: A prospective cohort study. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 296, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natale, A.; Turati, F.; Taborelli, M.; Giacosa, A.; Augustin, L.S.; Crispo, A.; Negri, E.; Rossi, M.; La Vecchia, C. Diabetes risk reduction diet and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2024, 33, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, M.; Bahrami, A.; Abdi, F.; Ghafouri-Taleghani, F.; Paydareh, A.; Jalali, S.; Heidari, Z.; Rashidkhani, B. Dietary Diabetes Risk Reduction Score (DDRRS) and Breast Cancer Risk: A Case-Control Study in Iran. Nutr. Cancer 2024, 76, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirrafiei, A.; Imani, H.; Ansari, S.; Kondrud, F.S.; Safabakhsh, M.; Shab-Bidar, S. Association between diabetes risk reduction diet score and risk of breast cancer: A case–control study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 55, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Sui, J.; Yang, W.; Sun, Q.; Ma, Y.; Simon, T.G.; Liang, G.; Meyerhardt, J.A.; Chan, A.T.; Giovannucci, E.L.; et al. Type 2 diabetes prevention diet and hepatocellular carcinoma risk in US men and women. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 1870–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Peng, C.; Rhee, J.J.; Farvid, M.S.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B.; Rosner, B.A.; Tamimi, R.; Eliassen, A.H. Prospective study of a diabetes risk reduction diet and the risk of breast cancer. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 1492–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Bravi, F.; Serraino, D.; Parazzini, F.; Crispo, A.; Augustin, L.S.A.; Negri, E.; La Vecchia, C.; Turati, F. Diabetes Risk Reduction Diet and Endometrial Cancer Risk. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, A.M.; Yang, P.F.; Peng, Y.; Gong, J.P.; Li, Z.; Zhong, G.C. Type 2 diabetes prevention diet and the risk of pancreatic cancer: A large prospective multicenter study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5595–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.E.; Bagheri, A.; Benisi-Kohansal, S.; Azadbakht, L.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Consumption of “Diabetes Risk Reduction Diet” and Odds of Breast Cancer Among Women in a Middle Eastern Country. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 744500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turati, F.; Bravi, F.; Rossi, M.; Serraino, D.; Mattioli, V.; Augustin, L.; Crispo, A.; Giacosa, A.; Negri, E.; La Vecchia, C. Diabetes risk reduction diet and the risk of breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2022, 31, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhong, G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, L.; Wan, H.; Luo, F. Association Between Diabetes Risk Reduction Diet and Lung Cancer Risk in 98,159 Participants: Results From a Prospective Study. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 855101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zeng, S.; Jiao, B.; Zhang, H.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X. Adherence to the Diabetes Risk Reduction Diet and Bladder Cancer Risk in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian (PLCO) Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2023, 32, 1726–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, G.; Turati, F.; Parazzini, F.; Augustin, L.S.A.; Serraino, D.; Negri, E.; La Vecchia, C. Diabetes risk reduction diet and ovarian cancer risk: An Italian case-control study. Cancer Causes Control 2023, 34, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Peng, L.; Luo, H.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Gu, H.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xiang, L. Adherence to diabetes risk reduction diet and the risk of head and neck cancer: A prospective study of 101,755 American adults. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1218632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Xu, Z.Q.; Luo, H.Y.; Ren, X.R.; Wei, Q.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Jiang, Y.H.; Tang, Y.H.; He, H.M.; et al. Association of diabetes risk reduction diet with renal cancer risk in 101,755 participants: A prospective study. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Buenosvinos, I.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Romanos-Nanclares, A.; Sánchez-Bayona, R.; de Andrea, C.E.; Domínguez, L.J.; Toledo, E. Dietary-Based Diabetes Risk Score and breast cancer: A prospective evaluation in the SUN project. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 81, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Laiton, L.; Luján-Barroso, L.; Nadal-Zaragoza, N.; Castro-Espin, C.; Jakszyn, P.; Panico, C.; Le Cornet, C.; Dahm, C.C.; Petrova, D.; Rodríguez-Palacios, D.Á.; et al. Diabetes-Related Dietary Patterns and Endometrial Cancer Risk and Survival in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, J.-Y.; Shen, Q.-M.; Li, Z.-Y.; Yang, D.-N.; Zou, Y.-X.; Tan, Y.-T.; Li, H.-L.; Xiang, Y.-B. Adherence to dietary guidelines and liver cancer risk: Results from two prospective cohort studies. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2025, 67, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morze, J.; Danielewicz, A.; Przybyłowicz, K.; Zeng, H.; Hoffmann, G.; Schwingshackl, L. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis on adherence to mediterranean diet and risk of cancer. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 1561–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Mohsenpour, M.; Fallah-Moshkani, R.; Ghiasvand, R.; Khosravi-Boroujeni, H.; Mehdi Ahmadi, S.; Brauer, P.; Salehi-Abargouei, A. Adherence to Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)-style diet and the risk of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2019, 38, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, M.E.; Akinyemiju, T.F. Meta-analysis of the association between dietary inflammatory index (DII) and cancer outcomes. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 2215–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri, G.; Nikrad, N.; Keshavari, S.; Jamshidi, S.; Fayyazishishavan, E.; Ardekani, A.M.; Farhangi, M.A.; Jafarzadeh, F. A high Diabetes Risk Reduction Score (DRRS) is associated with a better cardio-metabolic profile among obese individuals. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2023, 23, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorian, A.; Moradmand, Z.; Mirzaei, S.; Asadi, A.; Akhlaghi, M.; Saneei, P. Adherence to diabetes risk reduction diet is associated with metabolic health status in adolescents with overweight or obesity. Nutr. J. 2025, 24, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Athar, M.T.; Islam, M. Type 2 Diabetes, Obesity, and Cancer Share Some Common and Critical Pathways. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 600824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Qu, S. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and cancers and its underlying mechanisms. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 800995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.R.; Hu, T.Y.; Hao, F.B.; Chen, N.; Peng, Y.; Wu, J.J.; Yang, P.F.; Zhong, G.C. Type 2 Diabetes-Prevention Diet and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Prospective Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 191, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naugler, W.E.; Sakurai, T.; Kim, S.; Maeda, S.; Kim, K.; Elsharkawy, A.M.; Karin, M. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science 2007, 317, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, P.; Viguerie, N.; Massier, L.; Rydén, M.; Astrup, A.; Blaak, E.; Langin, D.; Andersson, D.P. Sex differences in adipose insulin resistance are linked to obesity, lipolysis and insulin receptor substrate 1. Int. J. Obes. 2024, 48, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omair, A. Selecting the appropriate study design: Case–control and cohort study designs. J. Health Spec./January 2016, 4, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Gan, X.; He, Y.; Nong, S.; Su, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, X.; Peng, X. Association between nut consumption and cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Nutr. Cancer 2022, 75, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Gao, M.; Li, X. Coffee intake and cancer: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. Shanghai J. Prev. Med. 2023, 35, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farvid, M.S.; Sidahmed, E.; Spence, N.D.; Mante Angua, K.; Rosner, B.A.; Barnett, J.B. Consumption of red meat and processed meat and cancer incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 937–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.; Liu, K.; Long, J.; Li, J.; Cheng, L. Dietary glycemic index, glycemic load and cancer risk: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 2115–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmons, D.R. Metabolic actions of insulin-like growth factor-I in normal physiology and diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 41, 425–443, vii–viii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D.; Tahimic, C.; Chang, W.; Wang, Y.; Philippou, A.; Barton, E.R. Role of IGF-I signaling in muscle bone interactions. Bone 2015, 80, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, S.; Cleveland, R.; Norat, T.; Biessy, C.; Rohrmann, S.; Linseisen, J.; Boeing, H.; Pischon, T.; Panico, S.; Agnoli, C. Serum levels of IGF-I, IGFBP-3 and colorectal cancer risk: Results from the EPIC cohort, plus a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 1702–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, M.J.; Hoover, D.R.; Yu, H.; Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; Rohan, T.E.; Manson, J.E.; Li, J.; Ho, G.Y.; Xue, X.; Anderson, G.L. Insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I, and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.; Tseng, Y.H.; Kahn, C.R. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptors act as ligand-specific amplitude modulators of a common pathway regulating gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 17235–17245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, B.A. Western nutrition and the insulin resistance syndrome: A link to breast cancer. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 53, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draznin, B. Mechanism of the mitogenic influence of hyperinsulinemia. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2011, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-C.; Chu, P.-Y.; Hsia, S.-M.; Wu, C.-H.; Tung, Y.-T.; Yen, G.-C. Insulin induction instigates cell proliferation and metastasis in human colorectal cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 50, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, T.; Kajio, H.; Sugiyama, T. Association between hyperinsulinemia and increased risk of cancer death in nonobese and obese people: A population-based observational study. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perseghin, G.; Calori, G.; Lattuada, G.; Ragogna, F.; Dugnani, E.; Garancini, M.P.; Crosignani, P.; Villa, M.; Bosi, E.; Ruotolo, G.; et al. Insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia and cancer mortality: The Cremona study at the 15th year of follow-up. Acta Diabetol. 2012, 49, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Pelzer, A.M.; Kiang, D.T.; Yee, D. Down-regulation of type I insulin-like growth factor receptor increases sensitivity of breast cancer cells to insulin. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinchuk, J.E.; Cao, C.; Huang, F.; Reeves, K.A.; Wang, J.; Myers, F.; Cantor, G.H.; Zhou, X.; Attar, R.M.; Gottardis, M. Insulin receptor (IR) pathway hyperactivity in IGF-IR null cells and suppression of downstream growth signaling using the dual IGF-IR/IR inhibitor, BMS-754807. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 4123–4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Chubak, J.; Boudreau, D.M.; Barlow, W.E.; Weiss, N.S.; Li, C.I. Diabetes Treatments and Risks of Adverse Breast Cancer Outcomes among Early-Stage Breast Cancer Patients: A SEER-Medicare Analysis. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 6033–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Chen, K.; Jia, X.; Tian, Y.; Dai, Y.; Li, D.; Xie, J.; Tao, M.; Mao, Y. Metformin Use Is Associated with Better Survival of Breast Cancer Patients with Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 2015, 20, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Xue, K.; Kan, J. Use of dietary fibers in reducing the risk of several cancer types: An umbrella review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, P.B.; Ha, S.E.; Vetrivel, P.; Kim, H.H.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, G.S. Functions of polyphenols and its anticancer properties in biomedical research: A narrative review. Transl. Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 7619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Didier, A.J.; Stiene, J.; Fang, L.; Watkins, D.; Dworkin, L.D.; Creeden, J.F. Antioxidant and anti-tumor effects of dietary vitamins A, C, and E. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayedi, A.; Rashidy-Pour, A.; Parohan, M.; Zargar, M.S.; Shab-Bidar, S. Dietary antioxidants, circulating antioxidant concentrations, total antioxidant capacity, and risk of all-cause mortality: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazelas, E.; Pierre, F.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; Szabo de Edelenyi, F.; Agaesse, C.; De Sa, A.; Lutchia, R.; Gigandet, S.; Srour, B. Nitrites and nitrates from food additives and natural sources and cancer risk: Results from the NutriNet-Santé cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 51, 1106–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twarda-Clapa, A.; Olczak, A.; Białkowska, A.M.; Koziołkiewicz, M. Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs): Formation, chemistry, classification, receptors, and diseases related to AGEs. Cells 2022, 11, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Pandey, M.K.; Tyagi, A.K.; Deb, L. Oxidative stress and cancer: Advances and challenges. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 5010423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteng, A.; Kersten, S. Mechanisms of action of trans fatty acids. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debras, C.; Chazelas, E.; Srour, B.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; de Edelenyi, F.S.; Agaësse, C.; De Sa, A.; Lutchia, R.; Gigandet, S. Artificial sweeteners and cancer risk: Results from the NutriNet-Santé population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1003950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Ou, J.; Peng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y. Gut Microbiota Metabolites and Chronic Diseases: Interactions, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Hendryx, M.; Manson, J.E.; Figueiredo, J.C.; LeBlanc, E.S.; Barrington, W.; Rohan, T.E.; Howard, B.V.; Reding, K.; Ho, G.Y. Intentional weight loss and obesity-related cancer risk. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019, 3, pkz054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number | First Author (Year) | Country | Study Design | Cancer Site | Sex | Sample Size | Age Range or Mean Age (y) | Dietary Assessment | Effects | Comparison | Adjustments | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Luo, X. (2019) [19] | USA | Cohort -NHS and HPFS | Liver | Both | Control: 137,608 Case: 160 | W: 30–55 M: 40–75 | FFQ | HR | Q4 vs. Q1 | Age, study period, gender, race, physical activity, smoking status, body mass index, aspirin use, alcohol intake, total calorie intake, and type 2 diabetes | 8 |

| 2 | Kang, J (2020) [20] | USA | Cohort-NHS and NHSII | Breast | Female | Control: 182,654 Case: 11,943 | 25–55 | FFQ | HR | Q5 vs. Q1 | race, family income; age at menarche, age at menopause, postmenopausal hormone use, oral contraceptive use history, parity, age at first birth, breastfeeding history, family history of breast cancer, history of benign breast disease, height, alcohol intake, total caloric intake, total vegetable intake, physical activity, and BMI at age 18 y, change in weight since age 18 y | 7 |

| 3 | Esposito, G. (2021) [21] | Italy | Case-Cntrol | Endometrial | Female | Control: 908 Case: 454 | 18–79 | FFQ | OR | High vs. medium-low | age, education, year of interview, BMI, physical activity, smoking, alcohol intake, history of diabetes, total energy intake, age at menarche, parity, menopausal status, use of oral contraceptives, and use of hormone replacement therapy | 8 |

| 4 | Huang, Y. (2021) [22] | USA | Cohort -PLCO | Pancreatic | Both | Control: 101,729 Case: 402 | 65.5 | FFQ | HR | Q4 vs. Q1 | Age, sex, smoking status, former smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, BMI, aspirin use, history of diabetes, family history of pancreatic cancer, and energy intake | 7 |

| 5 | Mousavi, SE. (2021) [23] | Iran | Case–Control | Breast | Female | Controls: 700 Cases: 350 | 62.5 | FFQ | OR | Q4 vs. Q1 | Age, energy intake, education, residency, family history of breast cancer, physical activity, marital status, smoking, alcohol consumption, supplement use, breastfeeding, menopausal status, and BMI | 7 |

| 6 | Turati, F. (2022) [24] | Italy | Case–Control | Breast | Female | Controls: 2588 Cases: 2569 | 23–74 | FFQ | OR | Q4 vs. Q1 | Study center, age, education, year of interview, BMI, physical activity, smoking, history of diabetes, parity, menopausal status, age at menopause, use of oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, family history of breast cancer, alcohol intake, and total energy intake. | 7 |

| 7 | Turati, F. (2022) [14] | Italy | Case–Control | Pancreatic | Both | Controls: 652 Cases: 326 | 34–80 | FFQ | OR | T3 vs. T1 | Age, sex, year of interview, education, BMI, tobacco smoking, history of diabetes, alcohol intake, and total energy intake | 8 |

| 8 | Zhang, Y. (2022) [25] | USA | Cohort -PLCO | Lung | Both | Control: 98,159 Case: 1632 | 65.5 | FFQ | HR | Q4 vs. Q1 | Age, sex, BMI, energy intake, family history of lung cancer, marital status, race/ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol intake, history of diabetes | 7 |

| 9 | Chen, Y. (2023) [26] | USA | Cohort -PLCO | Bladder | Both | Control: 99,001 Case: 761 | 62.41 | FFQ | HR | Q4 vs. Q1 | Age, sex, BMI, energy intake, family cancer history, marital status, race, cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake status, and diabetes history | 7 |

| 10 | Esposito, G. (2023) [27] | Italy | Case–Control | Ovarian | Female | Controls: 2411 Cases: 1031 | 17–79 | FFQ | OR | Q4 vs. Q1 | Age, center, year of interview, education, total energy intake, history of diabetes, menopausal status, parity, use of oral contraceptives, family history of ovarian/breast cancer | 7 |

| 11 | Mirrafiei, A. (2023) [18] | Iran | Case–Control | Breast | Female | Controls: 150 Cases: 149 | 24–73 | FFQ | OR | Q5 vs. Q1 | Age, energy intake, education, marital status, menopause status, alcohol use, smoking, use of vitamin supplements, medicines, medical history (diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia), history of hormone and oral contraceptive use, age at first menarche (year), time since menopause in postmenopausal women, weight at age 18 years, number of children, physical activity level, length of breastfeeding, family history of breast cancer, and body mass index | 8 |

| 12 | Wu, X. (2023) [28] | USA | Cohort -PLCO | Head and neck | Both | Control: 101,755 Case: 279 | 65.53 | FFQ | HR | Q vs. Q1 | Age, sex, race, marital status, educational level, BMI, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, drinking status, alcohol consumption, history of diabetes, family history of HNC, and energy from diet | 7 |

| 13 | Xiang, L. (2023) [29] | USA | Cohort -PLCO | Renal | Both | Control: 101,755 Cases: 446 | 65.5 | FFQ | HR | Q4 vs. Q1 | Age, sex, race, marital status, educational level, body mass index, smoking status, smoking pack-years, alcohol consumption, ibuprofen use, arm (intervention or control), family history of renal cancer, history of diabetes, history of hypertension, and energy intake from diet | 7 |

| 14 | Aguilera-Buenosvinos, I. (2024) [30] | Spain | Cohort-SUN | Breast | Female | Control: 10,810 Case: 147 | 35 | FFQ | HR | T3 vs. T1 | Age, height, years at university, family history of breast cancer, smoking status, lifetime tobacco exposure, physical activity, TV watching, alcohol intake, BMI, age of menarche, age at menopause, history of pregnancy, months of breastfeeding, use of hormone replacement therapy, energy intake, prevalence of diabetes, family history of diabetes, and use of oral contraceptives | 9 |

| 15 | Chen, Y. (2024) [15] | USA | Cohort-WHI | Liver | Female | Control: 98,786 Case: 216 | 50–79 | FFQ | HR | T3 vs. T1 | Age, energy intake, study group indicator (observational study, clinical trial), race/ethnicity, education, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, body mass index, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs use, oral contraceptive use, menopausal hormone therapy use, family history of cancer, self-reported liver disease, and self-reported diabetes | 9 |

| 16 | Mohammadzadeh, M. (2024) [17] | Iran | Case–Control | Breast | Female | Controls: 267 Cases: 134 | >30 | FFQ | OR | T3 vs. T1 | Age, BMI, physical activity, energy intake, smoking, first pregnancy age, cancer family history, marital status, education, and menopausal status | 7 |

| 17 | Natale, A. (2024) [16] | Italy | Case–Control | Colorectal | Both | Controls: 4154 Cases:1953 | 19–74 | FFQ | OR | T3 vs. T1 | sex, age, study center, education, occupational physical activity, body mass index, alcohol consumption, tobacco smoking, family history of intestinal cancer, aspirin use, menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use, and total energy intake. | 8 |

| 18 | Torres-Laiton, L (2025) [31] | Europe | Cohort -EPIC | Endometrial | Female | Control: 285,418 Case: 1955 | 50.13 | FFQ | HR | T3 vs. T1 | Age at recruitment and country, and adjusted by menopausal status, smoking status, ever use of hormone treatment for menopause and BMI | 9 |

| 19 | Tuo, J (2025) [32] | China | Cohort -SMHS and SWHS | Liver | Both | Control: 132,524 Case: 687 | 40–74 | FFQ | HR | T3 vs. T1 | Calorie intake, BMI, physical activity, education, smoking status, family history of liver cancer, medical history of chronic hepatitis and T2DM, and alcohol drinking status | 8 |

| Groups | n | Highest vs. Lowest Comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | I2 | PHeterogeneity | PBetween-group | ||

| Analysis on overall cancers | ||||||

| Overall analysis | 19 | 0.77 (0.71–0.84) | <0.001 | 59.7% | <0.001 | |

| Subgroup by study design | ||||||

| Case–control studies | 8 | 0.73 (0.67–0.80) | <0.001 | 0.0% | 0.751 | 0.008 |

| Cohort studies | 11 | 0.82 (0.74–0.90) | <0.001 | 59.6% | 0.006 | |

| Subgroup by gender | ||||||

| Female | 19 | 0.84 (0.78–0.91) | <0.001 | 38.6% | 0.045 | 0.009 |

| Male | 9 | 0.72 (0.63–0.81) | <0.001 | 30.8% | 0.172 | |

| Subgroup by geography region | ||||||

| USA | 8 | 0.76 (0.67–0.87) | <0.001 | 62.8% | 0.009 | 0.730 |

| Europe | 7 | 0.79 (0.67–0.90) | 0.001 | 69.8% | 0.003 | |

| Asia | 4 | 0.75 (0.57–0.98) | 0.035 | 29.0% | 0.238 | |

| Subgroup by cancer site | ||||||

| Female cacers | 9 | 0.82 (0.74–0.92) | 0.001 | 58.3% | 0.014 | 0.057 |

| Gastrointestinal cancers | 6 | 0.72 (0.62–0.83) | <0.001 | 38.3% | 0.151 | |

| Others | 4 | 0.78 (0.68–0.88) | <0.001 | 23.7% | 0.269 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maghsoudi, Z.; A. Alsanie, S.; Melaku, Y.A.; Sayyari, A.; Nouri, M.; Shoja, M.; Olang, B.; Yarizadeh, H.; Zamani, B. The Association of Dietary Diabetes Risk Reduction Score and the Risk of Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3802. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233802

Maghsoudi Z, A. Alsanie S, Melaku YA, Sayyari A, Nouri M, Shoja M, Olang B, Yarizadeh H, Zamani B. The Association of Dietary Diabetes Risk Reduction Score and the Risk of Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3802. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233802

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaghsoudi, Zahra, Saleh A. Alsanie, Yohannes Adama Melaku, Aliakbar Sayyari, Mehran Nouri, Marzieh Shoja, Beheshteh Olang, Habib Yarizadeh, and Behzad Zamani. 2025. "The Association of Dietary Diabetes Risk Reduction Score and the Risk of Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3802. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233802

APA StyleMaghsoudi, Z., A. Alsanie, S., Melaku, Y. A., Sayyari, A., Nouri, M., Shoja, M., Olang, B., Yarizadeh, H., & Zamani, B. (2025). The Association of Dietary Diabetes Risk Reduction Score and the Risk of Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients, 17(23), 3802. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233802