Protein-Calorie Malnutrition Is Associated with Altered Colonic Mucosal Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cohort Recruitment and Sample Collection

2.2. Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

2.3. Microbial Profiling

2.4. Subgroup Analysis

3. Results

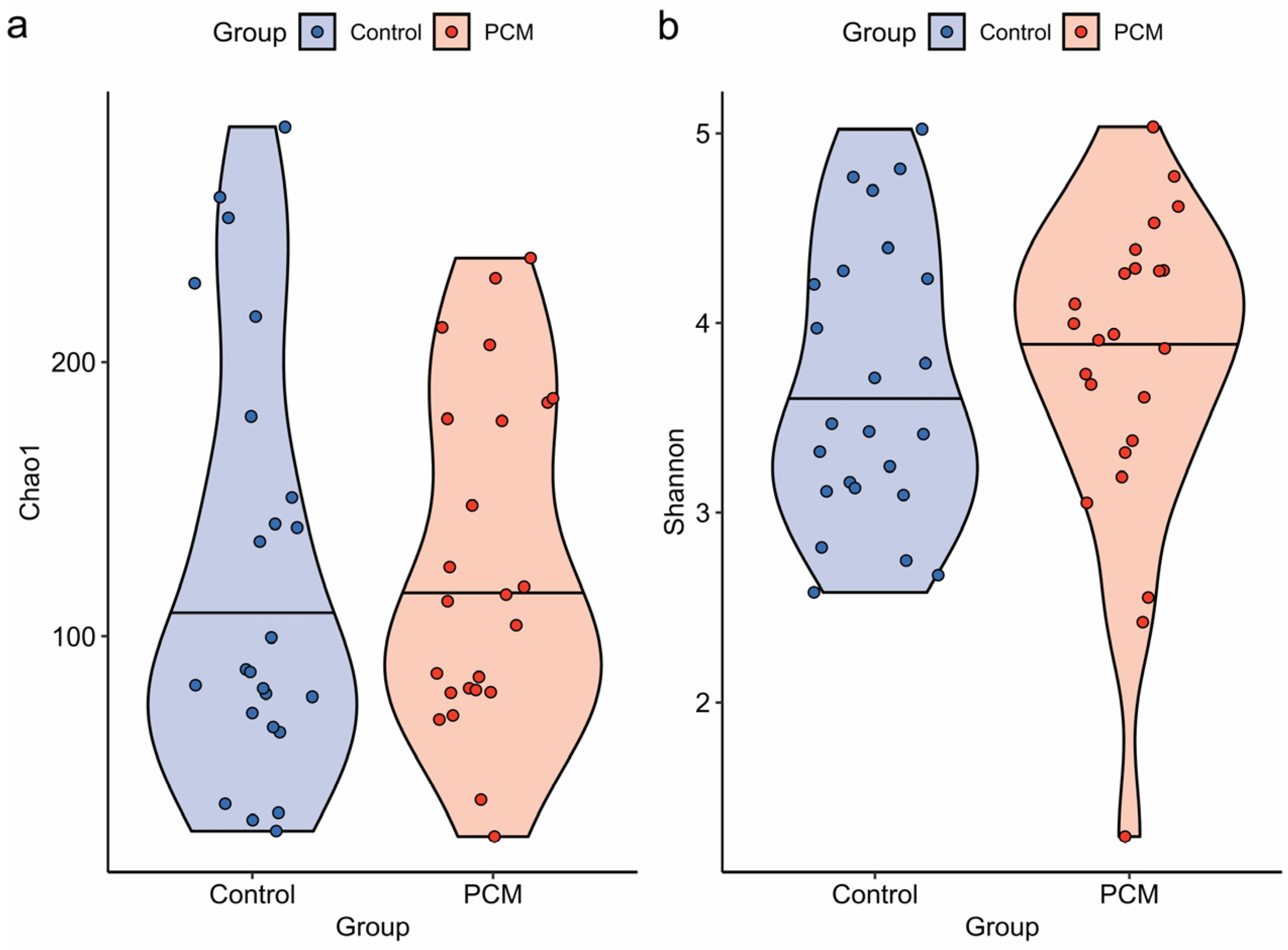

3.1. Microbial Diversity and Overall Composition of the Colonic Mucosal Microbiota Were Not Significantly Altered in IBD Patients with PCM Compared to Those Without PCM

3.2. Colonic Mucosal Microbiota of IBD Patients with PCM Were Characterized by Species-Level Differences in Taxonomic Abundance

3.3. Subgroup Analysis Revealed That Unclassified Blautia Was Significantly Decreased in Both the Overall Cohort and CD Subgroup

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCM | Protein-calorie malnutrition |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| ASV | Amplicon sequence variant |

| MANOVA | Multivariate analysis of variance |

| kNN | k-nearest neighbor |

| PCoA | Principal coordinates analysis |

| PERMANOVA | Permutational multivariate analysis of variance |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

References

- Dua, A.; Corson, M.; Sauk, J.S.; Jaffe, N.; Limketkai, B.N. Impact of malnutrition and nutrition support in hospitalised patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 57, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massironi, S.; Vigano, C.; Palermo, A.; Pirola, L.; Mulinacci, G.; Allocca, M.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S. Inflammation and malnutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, G.C.; Munsell, M.; Harris, M.L. Nationwide prevalence and prognostic significance of clinically diagnosable protein-calorie malnutrition in hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008, 14, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einav, L.; Hirsch, A.; Ron, Y.; Cohen, N.A.; Lahav, S.; Kornblum, J.; Anbar, R.; Maharshak, N.; Fliss-Isakov, N. Risk factors for malnutrition among IBD patients. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulley, J.; Todd, A.; Flatley, C.; Begun, J. Malnutrition and quality of life among adult inflammatory bowel disease patients. JGH Open 2020, 4, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumi, R.; Nakajima, K.; Iijima, H.; Wasa, M.; Shinzaki, S.; Nezu, R.; Inoue, Y.; Ito, T. Influence of nutritional status on the therapeutic effect of infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Surg. Today 2016, 46, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashash, J.G.; Elkins, J.; Lewis, J.D.; Binion, D.G. AGA Clinical practice update on diet and nutritional therapies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Expert review. Gastroenterology 2024, 166, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Bager, P.; Escher, J.; Forbes, A.; Hebuterne, X.; Hvas, C.L.; Joly, F.; Klek, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Ockenga, J.; et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 352–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti, M.; Ventura, G.; Jegatheesan, P.; Choisy, C.; Cynober, L.; De Bandt, J.P. Impact of qualitative and quantitative variations in nitrogen supply on catch-up growth in food-deprived-refed young rats. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J.; Smith, T. Malnutrition: Causes and consequences. Clin. Med. 2010, 10, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, A.D.; Xavier, R.J.; Gevers, D. The microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease: Current status and the future ahead. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwaly, A.; Reitmeier, S.; Haller, D. Microbiome risk profiles as biomarkers for inflammatory and metabolic disorders. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, J.P.; Goudarzi, M.; Lagishetty, V.; Li, D.; Mak, T.; Tong, M.; Ruegger, P.; Haritunians, T.; Landers, C.; Fleshner, P.; et al. Crohn’s disease in endoscopic remission, obesity, and cases of high genetic risk demonstrates overlapping shifts in the colonic mucosal-luminal interface microbiome. Genome Med. 2022, 14, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, G.T.; Osorio, E.Y.; Peniche, A.; Dann, S.M.; Cordova, E.; Preidis, G.A.; Suh, J.H.; Ito, I.; Saldarriaga, O.A.; Loeffelholz, M.; et al. Pathologic inflammation in malnutrition is driven by proinflammatory intestinal microbiota, large intestine barrier dysfunction, and translocation of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 846155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanton, L.V.; Barratt, M.J.; Charbonneau, M.R.; Ahmed, T.; Gordon, J.I. Childhood undernutrition, the gut microbiota, and microbiota-directed therapeutics. Science 2016, 352, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glockner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Waste not, want not: Why rarefying microbiome data is inadmissible. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, B.H.; Anderson, M.J. Fitting multivariate models to community data: A comment on distance-based redundancy analysis. Ecology 2001, 82, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Arze, C.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Schirmer, M.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Poon, T.W.; Andrews, E.; Ajami, N.J.; Bonham, K.S.; Brislawn, C.J.; et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature 2019, 569, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, X. Bifidobacterium Longum: Protection against inflammatory bowel disease. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 8030297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Hao, W.J.; Zhou, R.M.; Huang, C.L.; Wang, X.Y.; Liu, Y.S.; Li, X.Z. Pretreatment with Bifidobacterium longum BAA2573 ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis by modulating gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1211259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, X.; Li, Q.; Ji, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xie, J.; Nie, S. Bifidobacterium longum NSP001-derived extracellular vesicles ameliorate ulcerative colitis by modulating T cell responses in gut microbiota-(in)dependent manners. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, J.A.; Melton, S.L.; Yao, C.K.; Gibson, P.R.; Halmos, E.P. Dietary management of adults with IBD—The emerging role of dietary therapy. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 652–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Abe, T.; Tsuda, H.; Sugawara, T.; Tsuda, S.; Tozawa, H.; Fujiwara, K.; Imai, H. Lifestyle-related disease in Crohn’s disease: Relapse prevention by a semi-vegetarian diet. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2484–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Dong, C.; Lv, X.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, W.; Jamali, M.; Abedi, R.; Saedisomeolia, A. Probiotics and inflammatory bowel disease: An umbrella meta-analysis of relapse, recurrence, and remission outcomes. Nutr. Metab. 2025, 22, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, O.P.; Bueno, S.M.; Kalergis, A.M. Probiotics in inflammatory bowel disease: Microbial modulation and therapeutic prospects. Trends Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellani, M.; Karaja, M.; Zayour, N.; Sadek, Z.; Hotayt, B.; Hallal, M. Evaluating the efficacy of probiotics on disease progression, quality of life, and nutritional status among patients with Crohn’s disease: A multicenter, randomized, single-blinded controlled trial. Nutrients 2025, 17, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Garza, D.R.; Gonze, D.; Krzynowek, A.; Simoens, K.; Bernaerts, K.; Geirnaert, A.; Faust, K. Starvation responses impact interaction dynamics of human gut bacteria Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Roseburia intestinalis. ISME J. 2023, 17, 1940–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forslund, K.; Hildebrand, F.; Nielsen, T.; Falony, G.; Le Chatelier, E.; Sunagawa, S.; Prifti, E.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Gudmundsdottir, V.; Pedersen, H.K.; et al. Disentangling type 2 diabetes and metformin treatment signatures in the human gut microbiota. Nature 2015, 528, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Yeo, S.; Lee, T.; Han, Y.; Ryu, C.B.; Huh, C.S. Culture-based characterization of gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1538620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, L.; Zhou, Y.L.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, C.; Wang, Z.; Xuan, B.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yan, Y.; et al. Microbiome and metabolome features in inflammatory bowel disease via multi-omics integration analyses across cohorts. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Companys, J.; Gosalbes, M.J.; Pla-Paga, L.; Calderon-Perez, L.; Llaurado, E.; Pedret, A.; Valls, R.M.; Jimenez-Hernandez, N.; Sandoval-Ramirez, B.A.; Del Bas, J.M.; et al. Gut microbiota profile and its association with clinical variables and dietary intake in overweight/obese and lean subjects: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.H.; Chiu, C.T.; Yeh, P.J.; Pan, Y.B.; Chiu, C.H. Clostridium innocuum infection in hospitalised patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Infect. 2022, 84, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.S.; Spakowicz, D.J.; Hong, B.Y.; Petersen, L.M.; Demkowicz, P.; Chen, L.; Leopold, S.R.; Hanson, B.M.; Agresta, H.O.; Gerstein, M.; et al. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mao, B.; Gu, J.; Wu, J.; Cui, S.; Wang, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Blautia-a new functional genus with potential probiotic properties? Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1875796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, P.; Duan, Y.; Dai, H.; An, Y.; Cheng, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, C.; et al. Investigation of gut microbiome changes in type 1 diabetic mellitus rats based on high-throughput sequencing. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 124, 109873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulaiman, R.M.; Al-Quorain, A.A.; Al-Muhanna, F.A.; Piotrowski, S.; Kurdi, E.A.; Vatte, C.; Alquorain, A.A.; Alfaraj, N.H.; Alrezuk, A.M.; Robinson, F.; et al. Gut microbiota analyses of inflammatory bowel diseases from a representative Saudi population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023, 23, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Bourgonje, A.R.; Gacesa, R.; Jansen, B.H.; Bjork, J.R.; Bangma, A.; Hidding, I.J.; van Dullemen, H.M.; Visschedijk, M.C.; Faber, K.N.; et al. Mucosal host-microbe interactions associate with clinical phenotypes in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, K.; Mizuno, S.; Mikami, Y.; Sujino, T.; Saigusa, K.; Matsuoka, K.; Naganuma, M.; Sato, T.; Takada, T.; Tsuji, H.; et al. A single species of Clostridium subcluster XIVa decreased in ulcerative colitis patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 2802–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, S.; Anderson, J.M.; Nielsen, H.L.; Schachtschneider, C.; McCauley, K.E.; Ozcam, M.; Larsen, L.; Lynch, S.V.; Nielsen, H. Fecal microbiota is associated with extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2338244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.D.; Daniel, S.G.; Li, H.; Hao, F.; Patterson, A.D.; Hecht, A.L.; Brensinger, C.M.; Wu, G.D.; Bittinger, K.; Dine, C.D.; et al. Surgery for Crohn’s Disease Is Associated With a Dysbiotic Microbiome and Metabolome: Results From Two Prospective Cohorts. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 18, 101357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PCM (n = 24) | Control (n = 24) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32.5 (27.25–46.75) | 55 (34–63) | 0.007 |

| Gender | 0.009 | ||

| Male | 6 (25.0) | 15 (62.5) | |

| Female | 18 (75.0) | 9 (37.5) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 18.2 (17.2–22.6) | 24.9 (21.3–27.0) | 0.001 |

| Disease type | 1.000 | ||

| Crohn’s disease | 18 (75.0) | 18 (75.0) | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 6 (25.0) | 6 (25.0) | |

| Duration (years) | 9 (2–14.25) | 13.5 (7.25–34) | 0.038 |

| Location | 1.000 | ||

| Colonic | 20 (83.3) | 19 (79.2) | |

| Extracolonic only | 4 (16.7) | 5 (20.8) | |

| Medication | |||

| Immunomodulator/Steroid | 12 (50.0) | 13 (54.2) | 0.773 |

| Biologic | 14 (58.3) | 15 (62.5) | 0.768 |

| Biopsy site inflammation | 1.000 | ||

| Non-inflamed | 19 (79.2) | 20 (83.3) | |

| Inflamed | 5 (20.8) | 4 (16.7) | |

| Disease activity | 0.311 | ||

| Active | 10 (41.7) | 10 (41.7) | |

| Remission | 6 (25.0) | 10 (41.7) | |

| Unknown | 8 (33.3) | 4 (16.7) | |

| Montreal classification | |||

| Crohn’s disease, L1/L2/L3/+L4/NA | 4/5/8/1/1 | 5/2/9/4/2 | |

| Crohn’s disease, B1/B2/B3/+p/NA | 6/3/8/5/1 | 3/5/4/5/6 | |

| Ulcerative colitis, E1/E2/E3/NA | 1/3/1/1 | 0/1/4/1 | |

| History of bowel surgery | 0.562 | ||

| Yes | 10 (41.7) | 12 (50.0) | |

| No | 13 (54.2) | 10 (41.7) | |

| Unknown | 1 (4.2) | 2 (8.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, H.-J.; Corson, M.; Aja, E.; Spartz, E.; Limketkai, B.N.; Jacobs, J.P. Protein-Calorie Malnutrition Is Associated with Altered Colonic Mucosal Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3775. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233775

Yang H-J, Corson M, Aja E, Spartz E, Limketkai BN, Jacobs JP. Protein-Calorie Malnutrition Is Associated with Altered Colonic Mucosal Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3775. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233775

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Hyo-Joon, Melissa Corson, Ezinne Aja, Ellen Spartz, Berkeley N. Limketkai, and Jonathan P. Jacobs. 2025. "Protein-Calorie Malnutrition Is Associated with Altered Colonic Mucosal Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3775. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233775

APA StyleYang, H.-J., Corson, M., Aja, E., Spartz, E., Limketkai, B. N., & Jacobs, J. P. (2025). Protein-Calorie Malnutrition Is Associated with Altered Colonic Mucosal Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients, 17(23), 3775. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233775