Probiotic Supplementation Can Alter Inflammation Parameters and Self-Reported Sleep After a Marathon: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

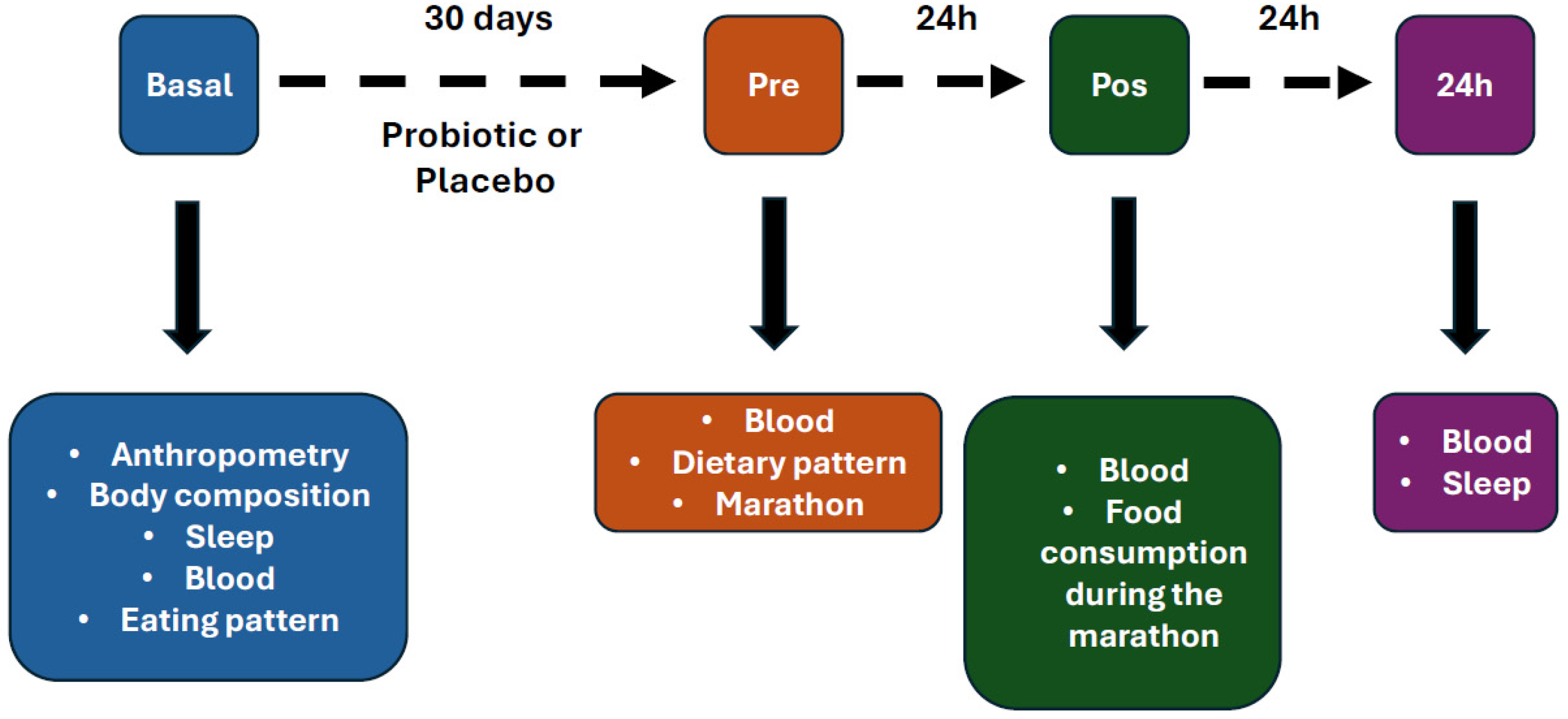

2. Methods

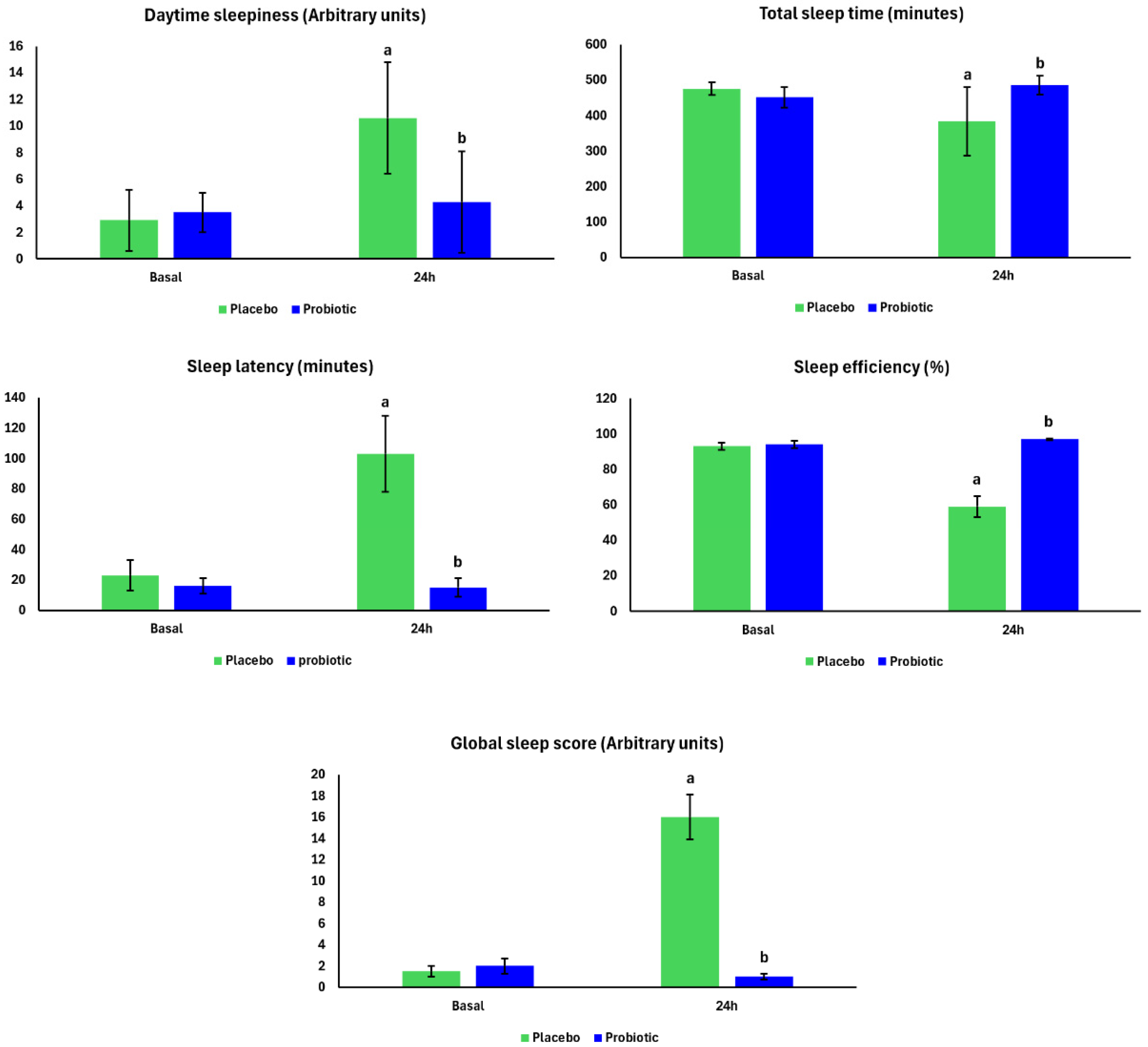

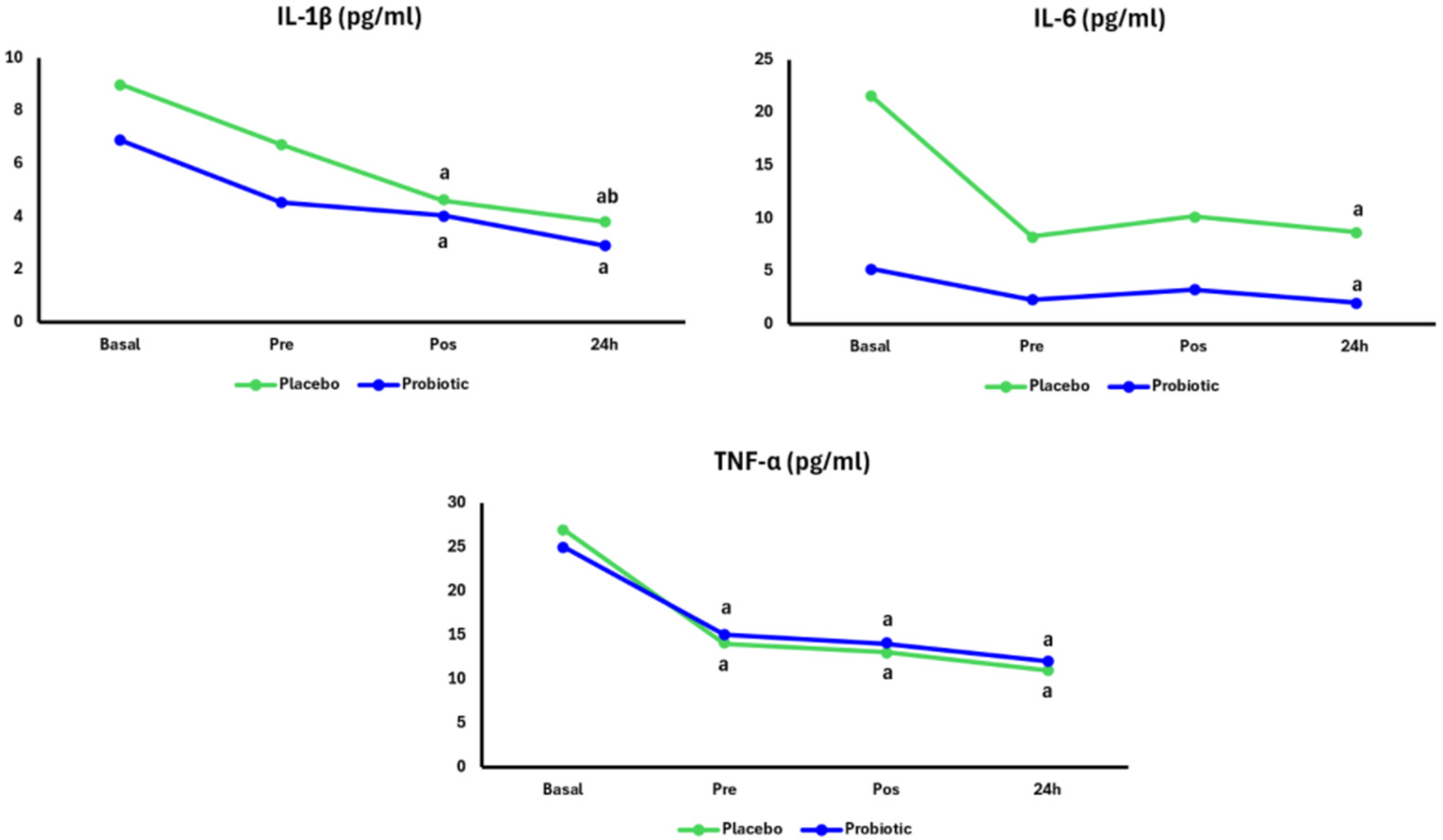

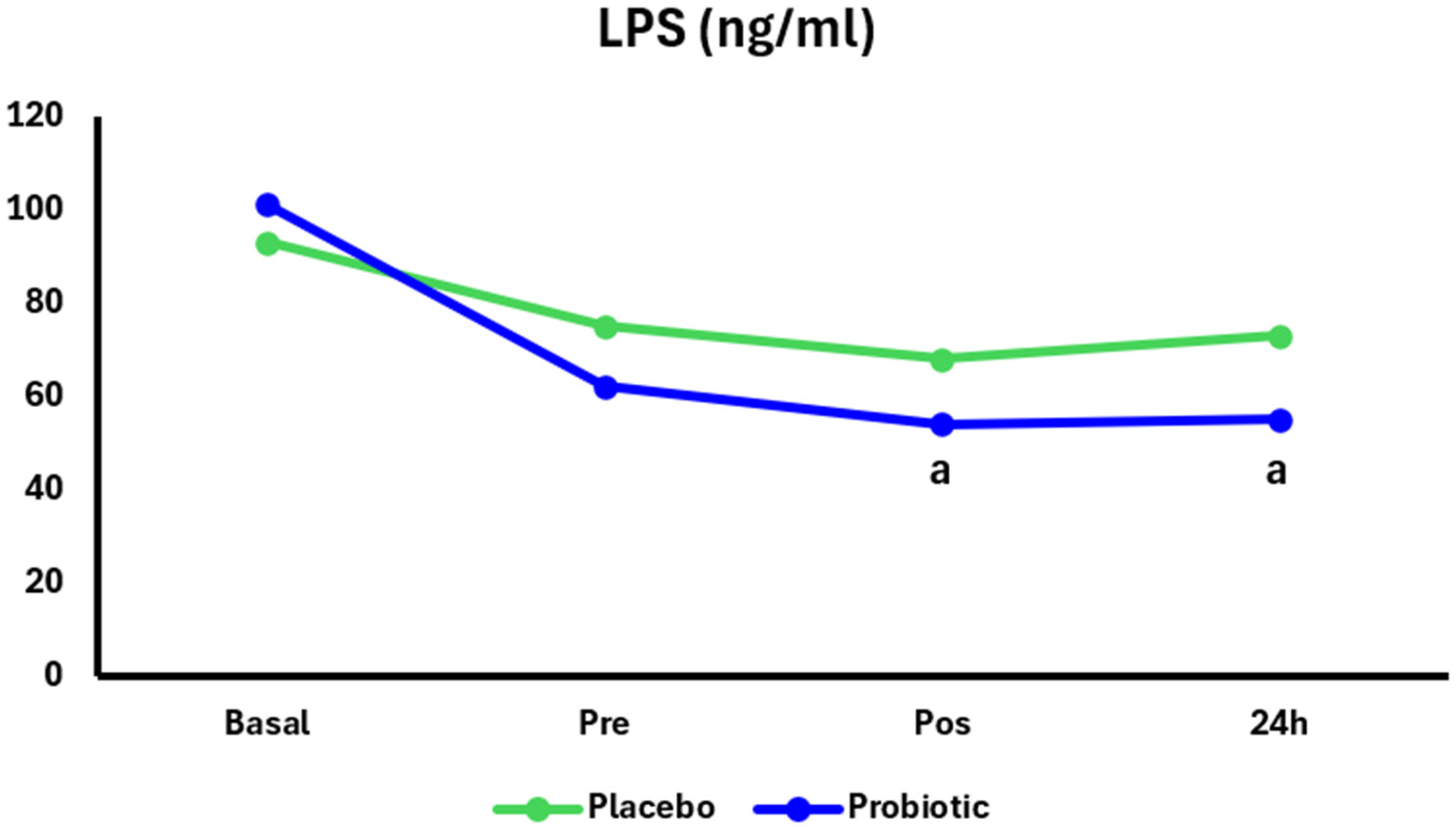

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fullagar, H.H.; Skorski, S.; Duffield, R.; Hammes, D.; Coutts, A.J.; Meyer, T. Sleep and athletic performance: The effects of sleep loss on exercise performance, and physiological and cognitive responses to exercise. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, N.P.; Halson, S.L.; Sargent, C.; Roach, G.D.; Nédélec, M.; Gupta, L.; Leeder, J.; Fullagar, H.H.; Coutts, A.J.; Edwards, B.J.; et al. Sleep and the athlete: Narrative review and 2021 expert consensus recommendations. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 55, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driver, H.S.; Rogers, G.G.; Mitchell, D.; Borrow, S.J.; Allen, M.; Luus, H.G.; Shapiro, C.M. Prolonged endurance exercise and sleep disruption. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994, 26, 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaidis, P.T.; Weiss, K.; Knechtle, B.; Trakada, G. Sleep in marathon and ultramarathon runners: A brief narrative review. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1217788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.; Molinero-Perez, A.; O’Riordan, K.J.; McCafferty, C.P.; O’Halloran, K.D.; Cryan, J.F. Microbiota and sleep: Awakening the gut feeling. Trends Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, E.A.; Nance, K.; Chen, S. The Gut-Brain Axis. Annu. Rev. Med. 2022, 73, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matenchuk, B.A.; Mandhane, P.J.; Kozyrskyj, A.L. Sleep, circadian rhythm, and gut microbiota. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2020, 53, 101340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, P.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Du, Y.; Jia, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wen, T.; Jia, Z.; et al. The relationship between inflammation, osteoporosis, and sleep disturbances: A cross-sectional analysis. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Yang, P.C.; Söderholm, J.D.; Benjamin, M.; Perdue, M.H. Role of mast cells in chronic stress induced colonic epithelial barrier dysfunction in the rat. Gut 2001, 48, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, E.; Gibson, O.R.; Stacey, M.; Hill, N.; Parsons, I.T.; Woods, D. Changes in gastrointestinal cell integrity after marathon running and exercise-associated collapse. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 121, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, D.C.; Henson, D.A.; Smith, L.L.; Utter, A.C.; Vinci, D.M.; Davis, J.M.; Kaminsky, D.E.; Shute, M. Cytokine changes after a marathon race. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 91, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagoulias, I.; Charokopos, N.; Thomas, I.; Spantidea, P.I.; de Lastic, A.L.; Rodi, M.; Anastasopoulou, S.; Aggeletopoulou, I.; Lazaris, C.; Karkoulias, K.; et al. Shifting gears: Study of immune system parameters of male habitual marathon runners. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1009065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, J.D.; Gratton, M.K.P.; Bender, A.M.; Werthner, P.; Lawson, D.; Pedlar, C.R.; Kipps, C.; Bastien, C.H.; Samuels, C.H.; Charest, J. Sleep Health, Individual Characteristics, Lifestyle Factors, and Marathon Completion Time in Marathon Runners: A Retrospective Investigation of the 2016 London Marathon. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.Y.; Li, S.; Ogamune, K.J.; Yuan, P.; Shi, X.; Ennab, W.; Ahmed, A.A.; Kim, I.H.; Hu, P.; Cai, D. Probiotic Lactobacillus johnsonii Reduces Intestinal Inflammation and Rebalances Splenic Treg/Th17 Responses in Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.D.; Suckling, C.A.; Peedle, G.Y.; Murphy, J.A.; Dawkins, T.G.; Roberts, M.G. An Exploratory Investigation of Endotoxin Levels in Novice Long Distance Triathletes, and the Effects of a Multi-Strain Probiotic/Prebiotic, Antioxidant Intervention. Nutrients 2016, 8, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, R.; Mohr, A.E.; Carpenter, K.C.; Kerksick, C.M.; Purpura, M.; Moussa, A.; Townsend, J.R.; Lamprecht, M.; West, N.P.; Black, K.; et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: Probiotics. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2019, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, C.; McCartney, D.; Desbrow, B.; Khalesi, S. Effects of probiotics and paraprobiotics on subjective and objective sleep metrics: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 1536–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, N.P.; Hughes, L.; Ramsey, R.; Zhang, P.; Martoni, C.J.; Leyer, G.J.; Cripps, A.W.; Cox, A.J. Probiotics, Anticipation Stress, and the Acute Immune Response to Night Shift. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 599547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.S.; Cha, L.; Sim, M.; Jung, S.; Chun, W.Y.; Baik, H.W.; Shin, D.M. Probiotic Supplementation Improves Cognitive Function and Mood with Changes in Gut Microbiota in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Trial. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2021, 76, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares-Silva, E.; Caris, A.V.; Santos, S.A.; Ravacci, G.R.; Thomatieli-Santos, R.V. Effect of Multi-Strain Probiotic Supplementation on URTI Symptoms and Cytokine Production by Monocytes after a Marathon Race: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, M.W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991, 14, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Mdel, C.; Benseñor, I.M.; Cardoso Lde, O.; Velasquez-Melendez, G.; Drehmer, M.; Pereira, T.S.; Faria, C.P.; Melere, C.; Manato, L.; Gomes, A.L.; et al. Reproducibility and relative validity of the Food Frequency Questionnaire used in the ELSA-Brasil. Cad. Saude Publica 2013, 29, 379–389. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, R.J.S.; Miall, A.; Khoo, A.; Rauch, C.; Snipe, R.; Camões-Costa, V.; Gibson, P. Gut-training: The impact of two weeks repetitive gut-challenge during exercise on gastrointestinal status, glucose availability, fuel kinetics, and running performance. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 42, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righetti, S.; Medoro, A.; Graziano, F.; Mondazzi, L.; Martegani, S.; Chiappero, F.; Casiraghi, E.; Petroni, P.; Corbi, G.; Pina, R.; et al. Effects of Maltodextrin-Fructose Supplementation on Inflammatory Biomarkers and Lipidomic Profile Following Endurance Running: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Cross-Over Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hynynen, E.; Vesterinen, V.; Rusko, H.; Nummela, A. Effects of moderate and heavy endurance exercise on nocturnal HRV. Int. J. Sports Med. 2010, 31, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeukendrup, A.E.; Vet-Joop, K.; Sturk, A.; Stegen, J.H.; Senden, J.; Saris, W.H.; Wagenmakers, A.J. Relationship between gastrointestinal complaints and endotoxaemia, cytokine release and the acute-phase reaction during and after a long-distance triathlon in highly trained men. Clin. Sci. 2000, 98, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.L.; Lee, H.J.; Edgett, B.A.; Romme, K.; Culos-Reed, S.N.; Lee, J.B. Exploring the effects of exercise on T cell function and metabolism in cancer: A scoping review protocol. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1655306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauss-Wegrzyniak, B.; Vraniak, P.D.; Wenk, G.L. LPS-induced neuroinflammatory effects do not recover with time. Neuroreport 2000, 11, 1759–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutsch, A.; Kantsjö, J.B.; Ronchi, F. The Gut-Brain Axis: How Microbiota and Host Inflammasome Influence Brain Physiology and Pathology. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 604179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szentirmai, É.; Buckley, K.; Massie, A.R.; Kapás, L. Lipopolysaccharide-mediated effects of the microbiota on sleep and body temperature. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, M.; Vieira, I.A.; Fino, L.C.; Gallina, D.A.; Esteves, A.M.; da Cunha, D.T.; Cabral, L.; Benatti, F.B.; Marostica Junior, M.R.; Batista, Â.G.; et al. Immune status, well-being and gut microbiota in military supplemented with synbiotic ice cream and submitted to field training: A randomised clinical trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 126, 1794–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monda, V.; Villano, I.; Messina, A.; Valenzano, A.; Esposito, T.; Moscatelli, F.; Viggiano, A.; Cibelli, G.; Chieffi, S.; Monda, M.; et al. Exercise Modifies the Gut Microbiota with Positive Health Effects. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 3831972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, J.M.; Yu, K.; Donaldson, G.P.; Shastri, G.G.; Ann, P.; Ma, L.; Nagler, C.R.; Ismagilov, R.F.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Hsiao, E.Y. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell 2015, 161, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.; Song, X.; Zhong, W.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Dietary fiber ameliorates sleep disturbance connected to the gut-brain axis. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 12011–12020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Febbraio, M.A. Muscle as an endocrine organ: Focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 1379–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.V.; Wu, W.T.; Chen, Y.H.; Chen, L.R.; Hsu, W.H.; Lin, Y.L.; Han, D.S. Enhanced serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, and -6 in sarcopenia: Alleviation through exercise and nutrition intervention. Aging 2023, 15, 13471–13485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K. Chronic Inflammation as an Immunological Abnormality and Effectiveness of Exercise. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haack, M.; Kraus, T.; Schuld, A.; Dalal, M.; Koethe, D.; Pollmächer, T. Diurnal variations of interleukin-6 plasma levels are confounded by blood drawing procedures. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2002, 27, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, C.A.Z.; Sierra, A.P.R.; Martínez Galán, B.S.; Maciel, J.F.S.; Manoel, R.; Barbeiro, H.V.; de Souza, H.P.; Cury-Boaventura, M.F. Time Course and Role of Exercise-Induced Cytokines in Muscle Damage and Repair After a Marathon Race. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 752144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batatinha, H.; Tavares-Silva, E.; Leite, G.S.F.; Resende, A.S.; Albuquerque, J.A.T.; Arslanian, C.; Fock, R.A.; Lancha, A.H., Jr.; Lira, F.S.; Krüger, K.; et al. Probiotic supplementation in marathonists and its impact on lymphocyte population and function after a marathon: A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Pascual, D.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A. The Effect of Probiotic Supplementation on Cytokine Modulation in Athletes After a Bout of Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. Open 2025, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, K.C.; Owens, R.; Hopkins, S.R.; Malhotra, A. Sleep Hygiene for Optimizing Recovery in Athletes: Review and Recommendations. Int. J. Sports Med. 2019, 40, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, N.S.; Gibbs, E.L.; Matheson, G.O. Optimizing sleep to maximize performance: Implications and recommendations for elite athletes. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2017, 27, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Yu, B.; Guan, G.; Wang, Y.; He, H. Effects of sleep deprivation on sports performance and perceived exertion in athletes and non-athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1544286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive Data of the Sample | ||||

| Placebo (n = 13) | Probiotic (n = 14) | |||

| Age (Years) | 40.46 ± 7.79 | 35.96 ± 5.81 | ||

| Stature (cm) | 1.75 ± 0.08 | 1.75 ± 0.06 | ||

| Body Mass (kg) | 74.12 ± 10.20 | 77.36 ± 10.99 | ||

| Self-reported food consumption during the marathon | ||||

| Placebo (n = 13) | Probiotic (n = 14) | |||

| Energy (Kcal) | 526.36 ± 317.97 | 678.20 ± 172.88 | ||

| Carbohydrates (g) | 109.07 ± 60.74 | 137.66 ± 112.66 | ||

| Proteins (g) | 4.60 ± 8.47 | 9.49 ± 29.55 | ||

| Fat total (g) | 7.98 ± 16.52 | 11.41± 28.33 | ||

| Fat saturated (g) | 0.79 ± 2.57 | 2.46 ± 8.44 | ||

| Fat Monounsaturated (g) | 0.12 ± 0.38 | 0.94 ± 3.47 | ||

| Fat polyunsaturated (g) | 0.23 ± 0.69 | 0.44 ± 1.54 | ||

| Cholesterol (mg) | 0 | 24.98 ± 93.29 | ||

| Fibers (g) | 1.58 ± 1.76 | 2.30 ± 4.20 | ||

| Self-reported usual food consumption | ||||

| Basal | Pre-marathon | |||

| Placebo (n = 13) | Probiotic (n = 14) | Placebo (n = 13) | Probiotic (n = 14) | |

| Energy (Kcal) | 2514.9 ± 962.95 | 2514.91 ± 962.95 | 2282.58 ± 577.50 | 2282.58 ± 577.50 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 342.78 ± 162.03 | 385.23 ± 197.14 | 317.32 ± 142.94 | 342.86 ± 164.30 |

| Proteins (g) | 106.90 ± 44.46 | 136.50 ± 97.96 | 88.85 ± 21.08 | 128.17 ± 30.70 |

| Fat total (g) | 104.0 ± 48.50 | 94.60 ± 40.39 | 74.64 ± 38.28 | 81.49 ± 34.61 |

| Fat saturated (g) | 36.81± 16.69 | 29.52 ± 22.40 | 24.24 ± 19.42 | 23.71± 10.51 |

| Fat Monounsaturated (g) | 21.62 ± 14.16 | 21.62 ± 14.16 | 11.31± 5.34 | 14.86 ± 6.96 |

| Fat polyunsaturated (g) | 8.66 ± 6.15 | 8.66 ± 6.15 | 13.17 ± 10.67 | 6.67 ± 4.66 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 474.41 ± 250.86 | 474.41 ± 250.86 | 377.64 ± 363.44 | 491.13 ± 397.00 |

| Fibers (g) | 23.65 ± 10.53 | 25.63 ± 15.61 | 24.92 ± 19.15 | 15.61 ± 15.25 |

| Total | Placebo | Probiotic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of symptoms | Yes (61.9%) | No (38.1%) | 38.1% | 23.8% |

| Placebo | Probiotic | |||

| Sometimes | Always | Sometimes | Always | |

| Stomach problems | 10% | - | 27% | - |

| Nausea | 0% | - | 0% | - |

| Dizziness | 10% | - | 9% | - |

| Flatulence | 60% | - | 18% | 9% |

| Urge to defecate | 40% | - | 45% | - |

| Burping | 30% | - | 27% | - |

| Heartburn | 0% | - | 9% | - |

| Bloating | 10% | - | 18% | - |

| Pain Stomach | 10% | - | 18% | - |

| Pain Intestinal | 0% | - | 9% | - |

| Feeling of wanting to vomit | 20% | - | 18% | - |

| Vomiting | 0% | - | 18% | - |

| Diarrhea | 0% | - | 0% | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aquino-Lemos, V.; Leite, G.S.F.; T. Silva, E.; Batatinha, H.A.P.; Resende, A.S.; Lancha-Junior, A.H.; R. Neto, J.C.; Tufik, S.; Thomatieli-Santos, R.V. Probiotic Supplementation Can Alter Inflammation Parameters and Self-Reported Sleep After a Marathon: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3762. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233762

Aquino-Lemos V, Leite GSF, T. Silva E, Batatinha HAP, Resende AS, Lancha-Junior AH, R. Neto JC, Tufik S, Thomatieli-Santos RV. Probiotic Supplementation Can Alter Inflammation Parameters and Self-Reported Sleep After a Marathon: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3762. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233762

Chicago/Turabian StyleAquino-Lemos, Valdir, Geovana S. F. Leite, Edgar T. Silva, Helena A. P. Batatinha, Ayane S. Resende, Antônio H. Lancha-Junior, José C. R. Neto, Sergio Tufik, and Ronaldo V. Thomatieli-Santos. 2025. "Probiotic Supplementation Can Alter Inflammation Parameters and Self-Reported Sleep After a Marathon: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3762. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233762

APA StyleAquino-Lemos, V., Leite, G. S. F., T. Silva, E., Batatinha, H. A. P., Resende, A. S., Lancha-Junior, A. H., R. Neto, J. C., Tufik, S., & Thomatieli-Santos, R. V. (2025). Probiotic Supplementation Can Alter Inflammation Parameters and Self-Reported Sleep After a Marathon: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients, 17(23), 3762. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233762