Associations of the Food Insecurity Experience Scale with Socioeconomic and Psychological Factors in Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

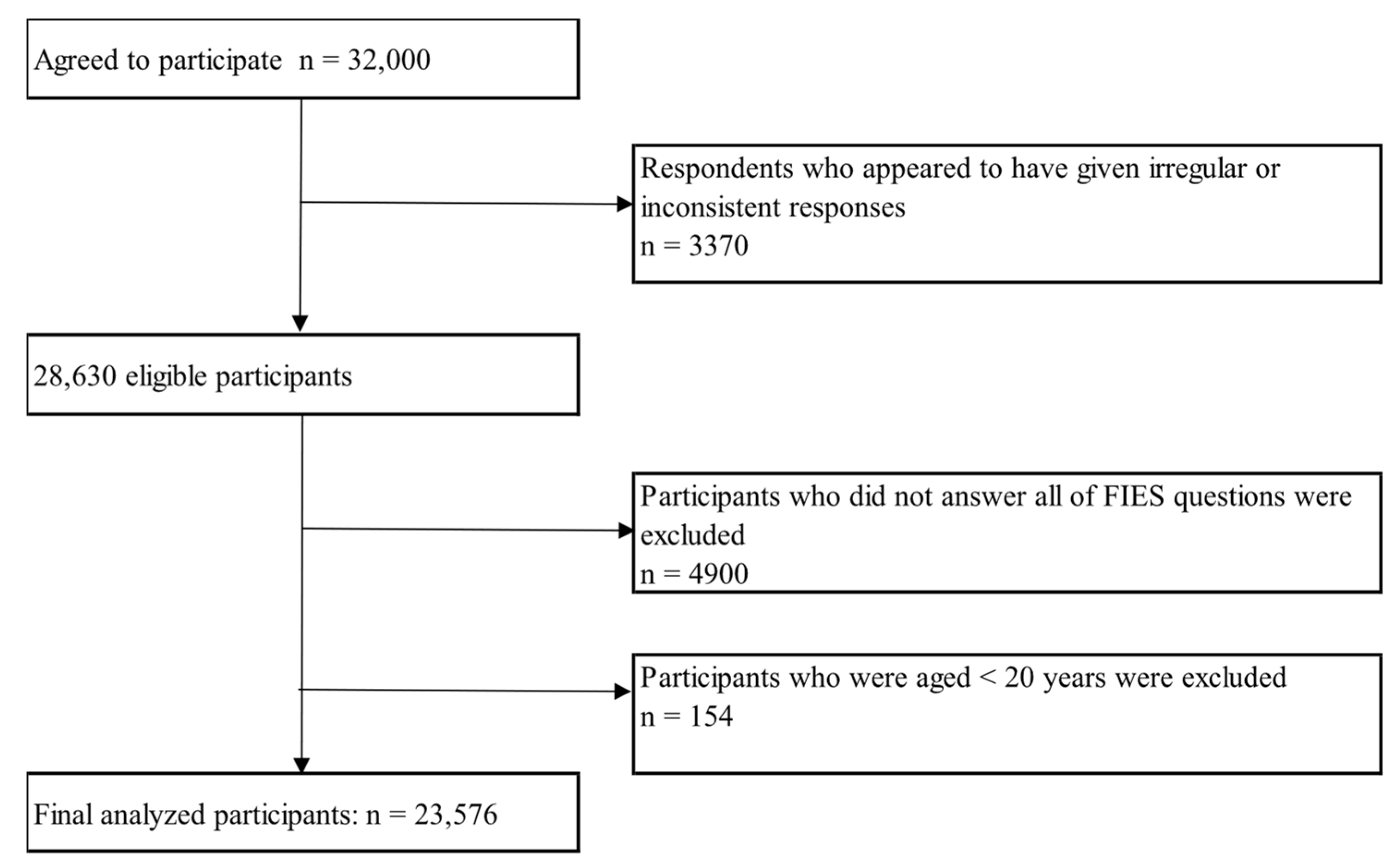

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES)

2.3. Statistical Validation of FIES Data

2.4. Sociodemographic and Socioeconomic Variables, Including Public Assistance

2.5. Severity of Psychological Distress

2.6. Statistical Analyses

2.7. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Item Parameters and FIES of Item Fit Statistics

3.2. Association Between Socioeconomic and Psychological Characteristics and Food Insecurity Experience Scale Score

3.3. Association Between Sociodemographic, Socioeconomic, Public Assistance Status, and Severity of Psychological Distress Characteristics and Food Insecurity Experience Scale Score Recommended by the FAO

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FI | Food insecurity |

| FIES | Food Insecurity Experience Scale |

| FImod + sev | moderate-to-severe food insecurity |

| FIsev | severe food insecurity |

| AOR | adjusted odds ratio |

| CI | confidence interval |

| K6 | Kessler Psychological Distress Scale |

References

- Skoet, J.; Stamoulis, K.G. The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2006: Eradicating World Hunger-Taking Stock Ten Years After the World Food Summit. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/a0750e/a0750e00.htm (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- UNICEF. In: Brief to the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/sofi-2024/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Pereira, M.; Oliveira, A.M. Poverty and food insecurity may increase as the threat of COVID-19 spreads. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 3236–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Haye, K.; Saw, H.W.; Miller, S.; Bruine de Bruin, W.; Wilson, J.P.; Weber, K.; Frazzini, A.; Livings, M.; Babboni, M.; Kapteyn, A. Ecological risk and protective factors for food insufficiency in Los Angeles County during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 1944–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltai, J.; Toffolutti, V.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. Prevalence and changes in food-related hardships by socioeconomic and demographic groups during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: A longitudinal panel study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 6, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kötzsche, M.; Teuber, R.; Jordan, I.; Heil, E.; Torheim, L.E.; Arroyo-Izaga, M. Prevalence and predictors of food insecurity among university students—Results from the Justus Liebig University Giessen, Germany. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 36, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, E.J.; Daly, C.; Kennedy, A. Prevalence of food insecurity among caregivers of young children during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland. Nutr. Bull. 2024, 49, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repella, B.M.; Rice, J.G.; Arroyo-Izaga, M.; Torheim, L.E.; Birgisdottir, B.E.; Jakobsdottir, G. Prevalence of Food Insecurity and Associations with Academic Performance, Food Consumption and Social Support among University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: FINESCOP Project in Iceland. Nutrients 2024, 16, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagiri, R.; Tabuchi, T.; Katanoda, K. Socioeconomic and sociodemographic factors associated with food expense insufficiency during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0279266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, T.J.; Kepple, A.W.; Cafiero, C. The Food Insecurity Experience Scale: Development of a Global Standard for Monitoring Hunger Worldwide. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/as583e (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Nord, M.; Cafiero, C.; Viviani, S. Methods for estimating comparable prevalence rates of food insecurity experienced by adults in 147 countries and areas. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2016, 772, 012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. SDG Indicators Data Portal. Available online: https://www.fao.org/sustainable-development-goals-data-portal/data/indicators/212-prevalence-of-moderate-or-severe-food-insecurity-in-the-population-based-on-the-food-insecurity-experience-scale/en?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Wambogo, E.A.; Ghattas, H.; Leonard, K.L.; Sahyoun, N.R. Validity of the Food Insecurity Experience Scale for Use in Sub-Saharan Africa and Characteristics of Food-Insecure Individuals. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2018, 2, nzy062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpyn, A.; Headley, M.G.; Knowles, Z.; Hepburn, E.; Kennedy, N.; Wolgast, H.K.; Riser, D.; Osei Sarfo, A.R. Validity of the Food Insecurity Experience Scale and prevalence of food insecurity in The Bahamas. Rural Remote Health 2021, 21, 6724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikomar, O.B.; Dean, W.; Ghattas, H.; Sahyoun, N.R. Validity of the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) for Use in League of Arab States (LAS) and Characteristics of Food Insecure Individuals by the Human Development Index (HDI). Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2021, 5, nzab017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankhotkaew, J.; Chandrasiri, O.; Charoensit, S.; Vongmongkol, V.; Tangcharoensathien, V. Thailand Prevalence and Profile of Food Insecurity in Households with under Five Years Children: Analysis of 2019 Multi-Cluster Indicator Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, M.; Miller, M.; Ballard, T.; Mitchell, D.C.; Hung, Y.W.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H. Does social support modify the relationship between food insecurity and poor mental health? Evidence from thirty-nine sub-Saharan African countries. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbiati, C.; Armando, A.; da Conceição, N.; Putoto, G.; Cavallin, F. Association between diabetes and food insecurity in an urban setting in Angola: A case-control study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Sarpong, O.J.; Abass, K.; Tutu, S.O.; Gyasi, R.M. Anxiety and sleep mediate the effect of food insecurity on depression in single parents in Ghana. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pool, U.; Dooris, M. Prevalence of food security in the UK measured by the Food Insecurity Experience Scale. J. Public Health 2022, 44, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. Prevalence of Moderate or Severe Food Insecurity in the Population (%)—Japan. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SN.ITK.MSFI.ZS?locations=JP&utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Poverty Rate. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/poverty-rate.html#indicator-chart (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Global Food Self-Sufficiency Rate. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/zyukyu/zikyu_ritu/013.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Miyawaki, A.; Tabuchi, T.; Tomata, Y.; Tsugawa, Y. Association between participation in the government subsidy programme for domestic travel and symptoms indicative of COVID-19 infection in Japan: Cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e049069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirai, T.; Hagiwara, K.; Chen, C.; Okubo, R.; Higuchi, F.; Matsubara, T.; Takahashi, M.; Nakagawa, S.; Tabuchi, T. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult physical, mental health, and abuse behaviors: A sex-stratified nationwide latent class analysis in Japan. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 369, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Voices of the Hungry, Applying the FIES. Available online: https://www.fao.org/in-action/voices-of-the-hungry/using-fies/en/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Boone, W.J. Rasch Analysis for Instrument Development: Why, When, and How? CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2016, 15, rm4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The Food Insecurity Experience Scale. Available online: https://www.fao.org/in-action/voices-of-the-hungry/analyse-data/en/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Nord, M.; Statistics, D. Introduction to Item Response Theory Applied to Food Security Measurement: Basic Concepts, Parameters and Statistics. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/i3946e (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Cafiero, C.; Nord, M.; Viviani, S.; Del Grossi, M.E.; Ballard, T.; Kepple, A.; Nwosu, C. Methods for Estimating Comparable Prevalence Rates of Food Insecurity Experienced by Adults Throughout the World. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/i4830e (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Cafiero, C.; Viviani, S.; Nord, M. Food security measurement in a global context: The food insecurity experience scale. Measurement 2018, 116, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.L.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T.A.; Kawakami, N.; Saitoh, M.; Ono, Y.; Nakane, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Tachimori, H.; Iwata, N.; Uda, H.; Nakane, H.; et al. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 17, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/20-21tyousa.html (accessed on 16 April 2025). (In Japanese).

- Okubo, R.; Yoshioka, T.; Nakaya, T.; Hanibuchi, T.; Okano, H.; Ikezawa, S.; Tsuno, K.; Murayama, H.; Tabuchi, T. Urbanization level and neighborhood deprivation, not COVID-19 case numbers by residence area, are associated with severe psychological distress and new-onset suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 287, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourmotabbed, A.; Moradi, S.; Babaei, A.; Ghavami, A.; Mohammadi, H.; Jalili, C.; Symonds, M.E.; Miraghajani, M. Food insecurity and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1778–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank of Japan. Time-Series Data Search, Key Time-Series Data Tables. Available online: https://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/ssi/mtshtml/fm08_m_1.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 13 September 2025). (In Japanese).

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024: Financing to End Hunger, Food Insecurity and Malnutrition in All Its Forms. Available online: https://doi.org/10.4060/cd1254en (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Statistics Bureau Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Consumer Price Index (CPI), Nationwide Average for 2024 (Base Year: 2020). Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/data/cpi/sokuhou/nen/pdf/zen-n.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025). (In Japanese).

- Raskind, I.G.; Haardörfer, R.; Berg, C.J. Food insecurity, psychosocial health and academic performance among college and university students in Georgia, USA. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, K.; Visentin, D.; Peterson, C.; Ayre, I.; Elliott, C.; Primo, C.; Murray, S. Severity of Food Insecurity among Australian University Students, Professional and Academic Staff. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruening, M.; Argo, K.; Payne-Sturges, D.; Laska, M.N. The struggle is real: A systematic review of food insecurity on postsecondary education campuses. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 1767–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, C.; Ziliak, J.P. Food insecurity research in the United States: Where we have been and where we need to go. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2018, 40, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, H.K.; Laraia, B.A.; Kushel, M.B. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruening, M.; Dinour, L.M.; Chavez, J.B.R. Food insecurity and emotional health in the USA: A systematic narrative review of longitudinal research. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 3200–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questions: Now I Would Like to Ask You Some Questions About Food. | Item |

|---|---|

| Q1. During the last 12 months, was there a time when you were worried you would not have enough food to eat because of a lack of money or other resources? | WORRIED |

| Q2. Still thinking about the last 12 months, was there a time when you were unable to eat healthy and nutritious food because of a lack of money or other resources? | HEALTHY |

| Q3. During the last 12 months, was there a time when you ate only a few kinds of foods because of a lack of money or other resources? | FEWFOOD |

| Q4. During the last 12 months, was there a time when you had to skip a meal because there was not enough money or other resources to get food? | SKIPPED |

| Q5. Still thinking about the last 12 months, was there a time when you ate less than you thought you should because of a lack of money or other resources? | ATELESS |

| Q6. In the past 12 months, was there a time when your household ran out of food because of a lack of money or other resources? | RUNOUT |

| Q7. In the past 12 months, was there a time when you were hungry but did not eat because of a lack of money or other resources for food? | HUNGRY |

| Q8. During the last 12 months, was there a time when you went without eating for a whole day because of a lack of money or other resources? | WHLDAY |

| Public Assistance Schemes | Brief Description of the Schemes |

|---|---|

| 1. Employment adjustment subsidy | This program provides subsidies to employers who are forced to scale down their business operations due to the impact of COVID-19 and implement employment adjustment in order to retain their employees. |

| 2. Public benefit for families with children | This measure provides temporary financial support to households with children, with the aim of mitigating the impact on these households and supporting their consumption. |

| 3. Subsidy for sustaining business | This program provides grants to businesses that have been particularly affected by the spread of COVID-19. |

| 4. Housing security Benefit | This program provides rent-equivalent benefits for a fixed period to individuals who are economically distressed and either have lost their housing or are at risk of losing it. |

| 5. Public assistance (welfare) | This program is designed to guarantee the minimum standard of living as stipulated by the Constitution for individuals facing financial hardship, while also actively supporting their efforts to achieve self-reliance. |

| 6. Unemployment benefit | This benefit is provided to help job seekers maintain a stable livelihood while aiming to return to work as quickly as possible. |

| 7.Disability benefit | This support provides financial assistance from the national or local government to individuals who face difficulties in daily life or employment due to a disability. |

| 8. Care allowance | The “care allowance” is a financial benefit or allowance provided to reduce the burden on family members or others who are caring for elderly or disabled individuals at home. |

| 9. Child rearing allowance | The “child rearing allowance” refers to financial benefits or allowances provided to families raising children, with the aim of offering economic support. |

| 10. Other assistance | Utilizing other public assistance programs that do not fall under 1–9. |

| Item | Item Severity | SE | Infit | Outfit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WORRIED | −1.723 | 0.062 | 1.246 | 2.163 |

| HEALTHY | −1.023 | 0.064 | 0.862 | 0.876 |

| FEWFOOD | −0.885 | 0.064 | 0.795 | 0.776 |

| SKIPPED | 0.771 | 0.080 | 0.946 | 0.991 |

| ATELESS | −0.805 | 0.065 | 0.899 | 0.875 |

| RUNOUT | 0.831 | 0.080 | 0.927 | 1.095 |

| HUNGRY | 0.513 | 0.076 | 1.022 | 1.017 |

| WHLDAY | 2.323 | 0.108 | 1.147 | 1.604 |

| All | Male | Female | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values (%) | FI Status (FIES Score) | AOR (95% CI) § | p-Value * | FI Status (FIES Score) | AOR (95% CI) § | FI Status (FIES Score) | AOR (95% CI) § | |||

| Food Security [0] | Food Insecurity [1–8] | Food Security [0] | Food Insecurity [1–8] | Food Security [0] | Food Insecurity [1–8] | |||||

| N | 21,804 | 1772 | - | 10,487 | 809 | - | 11,317 | 963 | - | |

| Number | 92.5 | 7.5 | - | 92.8 | 7.2 | - | 92.2 | 7.8 | - | |

| Number (weighted) | 92.2 | 7.9 | - | 93.0 | 7.0 | - | 91.5 | 0.8 | - | |

| Age | <0.001 | |||||||||

| 20–30 | 13.7 | 29.4 | 2.11 (1.56–2.85) | 11.8 | 27.8 | 2.29 (1.54–3.41) | 15.6 | 27.1 | 1.94 (1.26–2.98) | |

| 31–40 | 20.5 | 30.9 | 1.52 (1.17–1.97) | 21.6 | 29.5 | 1.38 (1.00–1.91) | 19.5 | 32.0 | 1.64 (1.10–2.43) | |

| 41–50 | 16.7 | 17.5 | Reference | 17.2 | 18.4 | Reference | 16.2 | 16.8 | Reference | |

| 51–60 | 15.3 | 11.7 | 0.77 (0.56–1.07) | 15.7 | 12.4 | 0.70 (0.46–1.06) | 15.0 | 11.1 | 0.87 (0.54–1.41) | |

| 61–70 | 17.5 | 6.08 | 0.26 (0.16–0.44) | 17.3 | 5.3 | 0.23 (0.11–0.51) | 17.6 | 6.7 | 0.28 (0.15–0.52) | |

| ≥71 | 16.3 | 6.45 | 0.26 (0.15–0.44) | 16.4 | 6.7 | 0.25 (0.11–0.54) | 16.2 | 6.3 | 0.26 (0.13–0.52) | |

| Female | 51.8 | 56.7 | 1.03 (0.82–1.29) | 0.048 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Education level | n = 21,722 | n = 1758 | <0.001 | n = 10,437 | n = 800 | n = 11,285 | n = 958 | |||

| High school or below | 53.7 | 53.4 | 1.22 (0.99–1.48) | 55.8 | 56.9 | 1.26 (0.98–1.63) | 52.0 | 50.8 | 1.16 (0.85–1.58) | |

| Two-year college graduate or technical school | 19.3 | 22.3 | 1.24 (1.01–1.53) | 10.8 | 12.6 | 1.13 (0.82–1.54) | 27.4 | 29.8 | 1.28 (0.97–1.70) | |

| University and above | 26.1 | 23.0 | Reference | 32.0 | 29.4 | Reference | 20.6 | 18.2 | Reference | |

| Unknown | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.15 (0.50–2.66) | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.01 (0.36–3.12) | 0.3 | 1.3 | 1.02 (0.35–3.51) | |

| Employment status | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Full-time employment/self-employed worker | 42.2 | 45.3 | Reference | 60.4 | 61.8 | Reference | 25.3 | 32.8 | Reference | |

| Part-time employment | 21.3 | 27.4 | 1.09 (0.83–1.41) | 14.1 | 19.9 | 1.47 (1.02–2.12) | 28.0 | 33.2 | 0.81 (0.57–1.16) | |

| Retired/homemaker/student | 24.1 | 18.4 | 1.05 (0.74–1.47) | 9.1 | 6.1 | 1.44 (0.72–2.88) | 38.1 | 27.8 | 0.80 (0.53–1.20) | |

| Unemployed | 12.4 | 8.8 | 1.03 (0.64–1.65) | 16.5 | 12.2 | 1.30 (0.67–2.55) | 8.5 | 6.3 | 0.77 (0.44–1.34) | |

| Number of people in the household | <0.001 | |||||||||

| 1 (participant only) | 14.7 | 22.2 | Reference | 14.5 | 27.1 | Reference | 15.0 | 18.5 | Reference | |

| 2 | 33.3 | 24.4 | 0.84 (0.63–1.11) | 32.9 | 21.0 | 0.62 (0.42–0.93) | 33.6 | 26.9 | 1.12 (0.76–1.67) | |

| 3 | 25.4 | 22.5 | 0.78 (0.59–1.03) | 25.0 | 24.1 | 0.76 (0.52–1.11) | 25.7 | 21.2 | 0.87 (0.58–1.30) | |

| ≥4 | 26.6 | 31.0 | 0.97 (0.73–1.30) | 27.6 | 27.9 | 0.74 (0.51–1.06) | 25.8 | 33.4 | 1.39 (0.89–2.17) | |

| Marital status | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| Married | 66.8 | 50.8 | Reference | 70.0 | 51.4 | Reference | 63.8 | 50.3 | Reference | |

| Unmarried | 22.2 | 37.1 | 1.10 (0.84–1.43) | 24.3 | 43.3 | 1.08 (0.77–1.52) | 20.3 | 32.4 | 0.98 (0.66–1.46) | |

| Divorced or bereaved | 11.0 | 12.1 | 1.46 (1.00–2.17) | 5.7 | 5.3 | 1.49 (0.93–2.37) | 16.0 | 17.3 | 1.38 (0.81–2.35) | |

| Annual household income † (Japanese yen) | n = 17,941 | n = 1520 | <0.0001 | n = 9098 | n = 724 | n = 18,818 | n = 643 | |||

| <1,000,000 | 2.4 | 6.7 | 3.60 (2.33–5.54) | 1.9 | 6.3 | 3.66 (1.86–7.19) | 2.8 | 7.0 | 4.51 (2.56–7.94) | |

| ≥1,000,000 & <5,000,000 | 36.5 | 47.1 | 2.11 (1.69–2.64) | 35.9 | 46.2 | 1.99 (1.46–2.70) | 37.1 | 47.9 | 2.43 (1.76–3.35) | |

| ≥5,000,000 & <10,000,000 | 32.1 | 24.4 | Reference | 36.6 | 28.8 | Reference | 28.0 | 47.9 | Reference | |

| ≥10,000,000 | 8.6 | 5.4 | 0.91 (0.59–1.75) | 10.7 | 8.4 | 1.02 (0.59–1.75) | 6.6 | 3.1 | 0.67 (0.39–1.16) | |

| Unknown | 20.3 | 16.4 | 1.11 (0.84–1.46) | 14.8 | 10.4 | 1.05 (0.73–1.62) | 25.5 | 20.9 | 1.11 (0.88–1.62) | |

| Public assistance status | ||||||||||

| Number of types of public assistance | <0.001 | |||||||||

| None | 79.9 | 74.0 | Reference | 80.9 | 74.3 | Reference | 78.9 | 73.8 | Reference | |

| ≥1 | 20.1 | 26.0 | 1.17 (1.00–1.47) | 19.1 | 25.7 | 1.25 (1.03–1.71) | 21.1 | 26.2 | 1.11 (1.03–1.54) | |

| Types of public assistance | ||||||||||

| Employment adjustment subsidy | 3.8 | 7.0 | 1.63 (1.18–2.25) | <0.001 | 8.3 | 3.8 | 1.91 (1.21–3.02) | 3.8 | 6.1 | 1.45 (0.93–2.26) |

| Public benefit for families with children | 12.9 | 16.3 | 1.04 (0.80–1.37) | <0.001 | 10.7 | 12.5 | 0.99 (0.64–1.52) | 14.4 | 22.9 | 1.45 (0.80–1.37) |

| Subsidy for sustaining business | 2.4 | 3.9 | 1.98 (1.10–3.57) | 0.002 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 1.72 (0.96–3.08) | 1.8 | 3.6 | 1.98 (1.10–3.57) |

| Housing security Benefit | 0.2 | 1.0 | 3.17 (1.18–8.53) | <0.001 | 0.30 | 1.6 | 3.55 (1.11–11.31) | 0.1 | 0.6 | 2.47 (0.38–16.11) |

| Public assistance (welfare) | 0.4 | 2.0 | 5.40 (2.24–12.97) | <0.001 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 3.90 (1.50–10.15) | 0.3 | 1.3 | 7.83 (1.75–35.0) |

| Unemployment benefit | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.30 (0.77–2.22) | <0.001 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 2.58 (1.42–4.69) | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.62 (0.29–1.35) |

| Disability benefit | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.12 (0.67–1.90) | <0.001 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 0.96 (0.67–1.90) | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.25 (0.55–2.80) |

| Care allowance | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.21 (0.34–4.31) | 0.109 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.46 (0.07–2.98) | 0.2 | 0.1 | 2.08 (0.55–7.93) |

| Child rearing allowance | 2.2 | 6.3 | 1.85 (1.15–2.97) | <0.001 | 1.6 | 3.8 | 2.34 (1.22–4.51) | 2.8 | 8.3 | 1.61 (0.86–2.99) |

| Other allowance | 5.3 | 8.4 | 1.92 (1.29–2.85) | <0.001 | 5.2 | 8.0 | 1.51 (0.88–2.60) | 5.5 | 8.7 | 2.50 (1.43–4.37) |

| Severity of psychological distress (K6 score) | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Normal (0–4) | 69.8 | 31.0 | Reference | 73.4 | 34.8 | Reference | 66.4 | 28.1 | Reference | |

| Possible mild mood or anxiety disorder (5–9) | 17.4 | 24.0 | 2.80 (2.19–3.59) | 14.9 | 20.8 | 2.73 (1.90–3.93) | 19.6 | 26.3 | 2.86 (2.04–4.01) | |

| Mood or anxiety disorder (>10) | 12.9 | 45.1 | 5.89 (4.74–7.33) | 11.7 | 44.4 | 6.19 (4.61–8.31) | 14.0 | 45.5 | 5.78 (4.18–7.98) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fujiwara, R.; Katagiri, R.; Tabuchi, T. Associations of the Food Insecurity Experience Scale with Socioeconomic and Psychological Factors in Japan. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3536. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223536

Fujiwara R, Katagiri R, Tabuchi T. Associations of the Food Insecurity Experience Scale with Socioeconomic and Psychological Factors in Japan. Nutrients. 2025; 17(22):3536. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223536

Chicago/Turabian StyleFujiwara, Rei, Ryoko Katagiri, and Takahiro Tabuchi. 2025. "Associations of the Food Insecurity Experience Scale with Socioeconomic and Psychological Factors in Japan" Nutrients 17, no. 22: 3536. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223536

APA StyleFujiwara, R., Katagiri, R., & Tabuchi, T. (2025). Associations of the Food Insecurity Experience Scale with Socioeconomic and Psychological Factors in Japan. Nutrients, 17(22), 3536. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223536