Intergenerational Transmission of Proactive Health Behaviors Among Adolescents with Overweight or Obesity: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy and Family Cohesion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measure

2.2.1. Parental Healthy Behaviors

2.2.2. General Self-Efficacy

2.2.3. Family Cohesion

2.2.4. Proactive Health Behaviors

2.2.5. Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

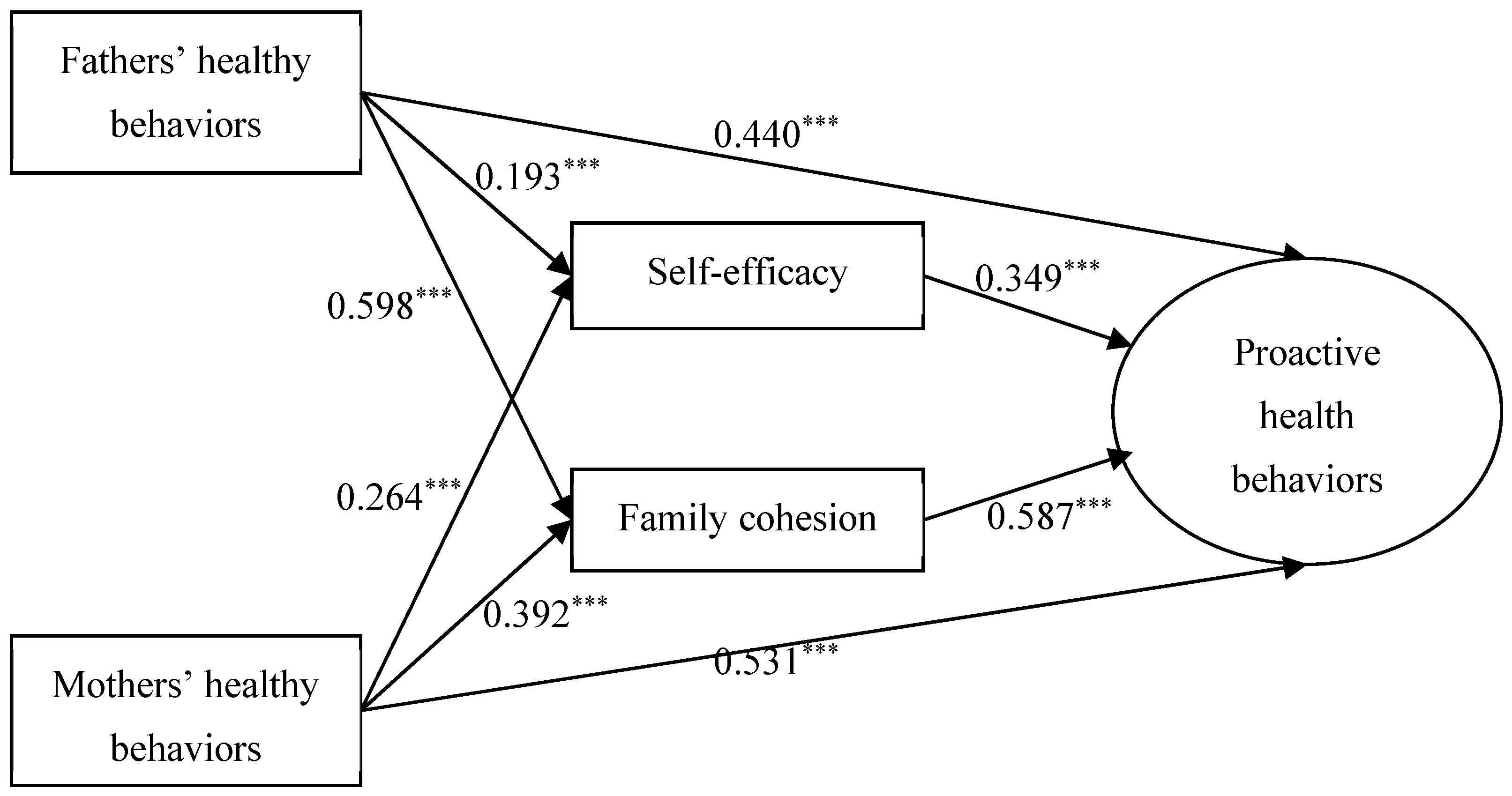

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewandowska, A.; Rudzki, G.; Lewandowski, T.; Bartosiewicz, A.; Próchnicki, M.; Stryjkowska-Góra, A.; Laskowska, B.; Sierpińska, M.; Rudzki, S.; Pavlov, S. Overweight and obesity among adolescents: Health-conscious behaviours, acceptance, and the health behaviours of their parents. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.; Dong, Y.; Chen, H.; Ma, L.; Jia, L.; Luo, J.; Liu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Ma, J.; Song, Y. Determinants of childhood obesity in China. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e1105–e1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.D.; Fu, E.; Kobayashi, M.A. Prevention and management of childhood obesity and its psychological and health comorbidities. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 16, 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Blanco, C.; Hernández-Martínez, A.; Parra-Fernández, M.L.; Onieva-Zafra, M.D.; Prado-Laguna, M.D.C.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J. Food addiction and lifestyle habits among university students. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sun, F.; Du, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, T.; Shi, X. Behavior-change lifestyle interventions for the treatment of obesity in children and adolescents: A scoping review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2025, 1543, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, K.; Ambrose, T.; Annis, A.; Ma, D.W.; Haines, J.; Guelph Family Health Study Family Advisory Council; on behalf of the Guelph Family Health Study. Putting family into family-based obesity prevention: Enhancing participant engagement through a novel integrated knowledge translation strategy. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Al-Ani, O.; Al-Ani, F. Children’s behaviour and childhood obesity. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2024, 30, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, A.; Hoeksema, H.; Murphy, R. Uncovering barriers and facilitators of weight loss and weight loss maintenance: Insights from qualitative research. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.L.; Kerr, D.A.; Fenner, A.A.; Straker, L.M. Adolescents just do not know what they want: A qualitative study to describe obese adolescents’ experiences of text messaging to support behavior change maintenance post intervention. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Yu, L.; Fan, K.; Hu, T.; Liu, L.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y. Associations between social support and proactive health behaviours among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of self-efficacy and peer relationships. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Wright, C.E.; Avishai, A.; Villegas, M.E.; Rothman, A.J.; Klein, W.M.P. Does increasing autonomous motivation or perceived competence lead to health behavior change? A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2021, 40, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.A.; Bolger, N.; Laurenceau, J.-P.; Patrick, H.; Oh, A.Y.; Nebeling, L.C.; Hennessy, E. Autonomous motivation and fruit/vegetable intake in parent—Adolescent dyads. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaelson, V.; Pilato, K.A.; Davison, C.M. Family as a health promotion setting: A scoping review of conceptual models of the health—Promoting family. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niermann, C.Y.; Gerards, S.M.; Kremers, S.P. Conceptualizing family influences on children’s energy balance-related behaviors: Levels of interacting family environmental subsystems (the LIFES Framework). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herke, M.; Knöchelmann, A.; Richter, M. Health and well-being of adolescents in different family structures in Germany and the importance of family climate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodolfo, A.; Richard, H. Health, locus of control, values, and the behavior of family and friends: An integrated approach to understanding preventive health behavior. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 5, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollborn, S.; James-Hawkins, L.; Lawrence, E.; Fomby, P. Health lifestyles in early childhood. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2014, 55, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Lv, R.; Zhao, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Song, P.; Li, Z.; Jia, P.; Zhang, H.; et al. Associations between parental adherence to healthy lifestyles and risk of obesity in offspring: A prospective cohort study in China. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11 (Suppl. S1), S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Godfrey, K.M.; Pasupathy, D.; Levin, J.; Flynn, A.C.; Hayes, L.; Briley, A.L.; Bell, R.; Lawlor, D.A.; Oteng-Ntim, E.; et al. Infant adiposity following a randomised controlled trial of a behavioural intervention in obese pregnancy. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrin, C.M.; Heinen, M.M.; Kelleher, C.C. Are dietary patterns of mothers during pregnancy related to children’s weight status? Evidence from the lifeways cross- generational cohort study. AIMS Public Health 2015, 2, 274–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, L.A.; Jackson, B.; Gibson, L.Y.; Doust, J.; Dimmock, J.A.; Davis, E.A.; Price, L.; Budden, T. ‘It’s been a lifelong thing for me’: Parents’ experiences of facilitating a healthy lifestyle for their children with severe obesity. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGeown, S.P.; Putwain, D.; Simpson, E.G.; Boffey, E.; Markham, J.; Vince, A. Predictors of adolescents’ academic motivation: Personality, self-efficacy and adolescents’ characteristics. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2014, 32, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.S.; Huelsnitz, C.O.; Rothman, A.J.; Simpson, J.A. Associations Between Parents’ Health and Social Control Behaviors and Their Adolescent’s Self-Efficacy and Health Behaviors: Insights From the Family Life, Activity, Sun, Health, and Eating (FLASHE) survey. Ann. Behav. Med. 2022, 56, 920–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleppang, A.L.; Steigen, A.M.; Finbråten, H.S. Explaining variance in self-efficacy among adolescents: The association between mastery experiences, social support, and self-efficacy. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzielska, A.; Mazur, J.; Nałęcz, H.; Oblacińska, A.; Fijałkowska, A. Importance of self-efficacy in eating behavior and physical activity change of overweight and non-overweight adolescent girls participating in healthy me: A lifestyle intervention with mobile technology. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Feng, W.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, T. The association between physical activity, self-efficacy, stress self-management and mental health among adolescents. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.K.; Buehler, C. Family cohesion and enmeshment: Different constructs, different effects. J. Marriage Fam. 1996, 58, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeb, B.T.; Chan, S.Y.S.; Conger, K.J.; Martin, M.J.; Hollis, N.D.; Serido, J.; Russell, S.T. The prospective effects of family cohesion on alcohol-related problems in adolescence: Similarities and differences by race/ethnicity. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 1941–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, W.Y.; Mohamad, N.; Law, L.S. Factors associated with binge eating behavior among malaysian adolescents. Nutrients 2018, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Yun, Q.; Jiang, X.; Chang, C. Family ses, family social capital, and general health in Chinese adults: Exploring their relationships and the gender-based differences. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Commission. Screening for Overweight and Obesity Among School-Age Children and Adolescents; National Health Commission: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Hong, Y.; Hua, J. SES differences in intergenerational transmission of health behaviors: An empirical research based on CHNS2015. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. 2020, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hu, Z.; Liu, Y. Evidences for reliability and validity of the Chinese version of General Self-Efficacy Scale. Chin. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 7, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, L.; Shen, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, J.P.; Jiang, S.A.; Wang, L.W.; Wang, X.D. The preliminary evaluation of the “Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale” and the “Family Environment Scale”—A comparative study between normal families and families with schizophrenia members. Chin. Ment. Health J. 1991, 5, 198–202+238. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.J.; Liu, J.B. How does parental phubbing affect children’s nature connectedness? An analysis based on the combined effects of parental mindfulness and family cohesion. Stud. Early Child. Educ. 2025, 6, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Lu, Z.; Li, S.; Yu, L.; Hu, T.; Liu, L.; Zhou, Y. Development and reliability and validity testing of the proactive health behavior scale for adolescents. Mod. Prev. Med. 2024, 51, 3529–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, L.H.; Wilfley, D.E.; Kilanowski, C.; Quattrin, T.; Cook, S.R.; Eneli, I.U.; Geller, N.; Lew, D.; Wallendorf, M.; Dore, P.; et al. Family-based behavioral treatment for childhood obesity implemented in pediatric primary care: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2023, 329, 1947–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Verdery, A.M.; Margolis, R. Sibling availability, sibling sorting, and subjective health among Chinese adults. Demography 2024, 61, 797–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, N.F.; Katzman, K.; Danzo, S.; McCarty, C.A.; Richardson, L.P.; Ford, C.A. Triadic collaboration between adolescents, caregivers, and health-care providers to promote healthy behavior. J. Adolesc. Health 2024, 74, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, H.B.; Domingue, B.; Nagata, J.M.; Cislaghi, B.; Weber, A.; Darmstadt, G.L. Adolescent gender norms and adult health outcomes in the USA: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2019, 3, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebel-Schwalm, M.S. Family pressure and support on young adults’ eating behaviors and body image: The role of gender. Appetite 2024, 196, 107262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottorff, J.L.; Seaton, C.L.; Johnson, S.T.; Caperchione, C.M.; Oliffe, J.L.; More, K.; Jaffer-Hirji, H.; Tillotson, S.M. An updated review of interventions that include promotion of physical activity for adult men. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 775–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willemsen, Y.; Vacaru, S.; Beijers, R.; Weerth, C.D. Are adolescent diet quality and emotional eating predicted by history of maternal caregiving quality and concurrent inhibitory control? Appetite 2023, 190, 107020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snelling, A.; Hawkins, M.; McClave, R.; Belson, S.I. The role of teachers in addressing childhood obesity: A school-based approach. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topping, K.J. Peer intervention in obesity and physical activity: Effectiveness and implementation. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2025, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, P.Y.; Chua, J.Y.X.; Chan, P.Y.; Shorey, S. Effectiveness of universal community engagement childhood obesity interventions at improving weight-related and behavioral outcomes among children and adolescents: A systematic eview and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultner, D.T.; Lindström, B.R.; Cikara, M.; Amodio, D.M. Transmission of social bias through observational learning. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, K.E.; Gardner, L.A.; McCann, K.; Hunter, E.; Parmenter, B.; Aitken, T.; Chapman, C.; Spring, B.; Thornton, L.; Slade, T.; et al. Parent-based interventions to improve multiple lifestyle risk behaviors among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2022, 164, 107247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, I.; Koivuniemi, E.; Vahlberg, T.; Raats, M.M.; Laitinen, K. Self-reported parental healthy dietary behavior relates to views on child feeding and health and diet quality. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larruy-García, A.; Mahmood, L.; Miguel-Berges, M.L.; Masip, G.; Seral-Cortés, M.; Miguel-Etayo, P.D.; Moreno, L.A. Diet quality scores, obesity and metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2024, 13, 755–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollborn, S.; Pace, J.A.; Rigles, B. Children’s health lifestyles and the perpetuation of inequalities. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2025, 66, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnis, N. Long-term health effects of childhood parental income. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 317, 115607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vida, M.; Camille, P. The consolidation of education and health in families. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2021, 86, 670–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAnally, K.; Hagger, M. Health literacy, social cognition constructs, and health behaviors and outcomes: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2023, 42, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, E.J.; Haag, D.G.; Spencer, A.J.; Roberts-Thomson, K.; Jamieson, L.M. Self-efficacy and oral health outcomes in a regional Australian Aboriginal population. BMC Oral. Health 2022, 22, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, R.D. Enjoyment, self-efficacy, and physical activity within parent-adolescent dyads: Application of the actor-partner interdependence model. Prev. Med. 2019, 126, 105756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosco, G.; Lee, H.; Feinberg, M.E.; Fang, S.; Sloan, C.J. COVID-19 family dynamics and health protective behavior adherence: A 16-wave longitudinal study. Health Psychol. 2023, 42, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrady, B.; Tonigan, J.S.; Fink, B.C.; Chávez, R.; Martinez, A.D.; Borders, A.; Fokas, K.; Epstein, E.E. A randomized pilot trial of brief family-involved treatment for alcohol use disorder: Treatment engagement and outcomes. Psycho Add. Behav. 2023, 37, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, V.; Delaney, C.; Eck, K.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C. Family social capital: Links to weight-related and parenting behaviors of mothers with young children. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franko, D.; Thompson, D.; Bauserman, R.; Fau, A.S.; Striegel-Moore, R.H. What’s love got to do with it? Family cohesion and healthy eating behaviors in adolescent girls. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2008, 41, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Forbush, K.; Swanson, T.J. The impact of discrimination on binge eating in a nationally representative sample of Latine individuals. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N (%) | Proactive Health Behaviors Scores (M ± SD) | Z/H | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 4932 | 86.50 ± 18.78 | 18.20 b | 0.003 |

| Gender | −4.63 a | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 1808 (37.66) | 88.36 ± 19.53 | ||

| Male | 3124 (63.34) | 90.82 ± 20.33 | ||

| Ethnicity | −0.68 a | 0.500 | ||

| Minority | 87 (1.76) | 88.23 ± 20.84 | ||

| Han | 4845 (98.24) | 89.95 ± 20.07 | ||

| Accommodation | 2.55 a | 0.011 | ||

| Boarding | 4367 (88.54) | 90.23 ± 19.88 | ||

| Non-boarding | 565 (11.46) | 87.55 ± 21.38 | ||

| Father’s education attainment | 94.28 b | <0.001 | ||

| Primary or below | 138 (2.80) | 79.93 ± 24.30 | ||

| Junior high school | 1717 (34.81) | 87.80 ± 20.19 | ||

| Senior high school | 1680 (34.06) | 89.71 ± 19.89 | ||

| College or higher | 1397 (28.33) | 93.77 ± 18.96 | ||

| Mother’s education attainment | 94.44 b | <0.001 | ||

| Primary or below | 263 (5.33) | 80.88 ± 22.38 | ||

| Junior high school | 1753 (35.54) | 88.09 ± 20.33 | ||

| Senior high school | 1531 (31.04) | 90.61 ± 19.86 | ||

| College or higher | 1385 (28.09) | 93.19 ± 18.75 | ||

| Only child | −5.03 a | <0.001 | ||

| Multiple-child | 3105 (62.96) | 88.78 ± 20.30 | ||

| Only child | 1827 (37.04) | 91.86 ± 19.55 | ||

| Family economic status | 296.17 b | <0.001 | ||

| Poor | 211 (4.28) | 75.20 ± 23.53 | ||

| Normal | 2290 (46.43) | 86.44 ± 19.33 | ||

| Good | 2431 (49.29) | 94.17 ± 19.17 | ||

| Region | 3.85 a | <0.001 | ||

| Rural | 1936 (39.25) | 91.09 ± 20.37 | ||

| Urban | 2996 (60.75) | 89.17 ± 19.86 | ||

| Areas | 4.58 a | <0.001 | ||

| Coastal | 2658 (50.23) | 91.13 ± 19.85 | ||

| Inland | 2274 (49.77) | 88.51 ± 20.26 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | p | β | 95% CI | p | β | 95% CI | p | β | 95% CI | p | |

| Father’s healthy behaviors | 1.090 | 0.889, 1.291 | <0.001 | 0.847 | 0.654, 1.039 | <0.001 | 0.534 | 0.354, 0.715 | <0.001 | 0.442 | 0.263, 0.620 | <0.001 |

| Mother’s healthy behaviors | 0.845 | 0.629, 1.061 | <0.001 | 0.641 | 0.434, 0.847 | <0.001 | 0.500 | 0.307, 0.692 | <0.001 | 0.525 | 0.336, 0.714 | <0.001 |

| Age | −1.545 | −2.217, −0.873 | <0.001 | −1.382 | −2.006, −0.757 | <0.001 | −1.206 | −1.826, −0.586 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | 1.777 | 0.736, 2.818 | 0.001 | 1.146 | 0.178, 2.114 | 0.020 | 1.184 | 0.226, 2.142 | 0.015 | |||

| Ethnicity | 0.338 | −3.466, 4.142 | 0.862 | 0.510 | −3.025, 4.045 | 0.777 | 0.412 | −3.063, 3.886 | 0.816 | |||

| Accommodation | 0.465 | −1.149, 2.079 | 0.572 | 0.841 | −0.659, 2.341 | 0.272 | −0.154 | −1.658, 1.350 | 0.841 | |||

| Self-efficacy | 0.735 | 0.665, 0.806 | <0.001 | 0.379 | 0.308, 0.449 | <0.001 | 0.354 | 0.285, 0.423 | <0.001 | |||

| Father educational attainment | ||||||||||||

| Junior high school | 3.568 | 0.271, 6.866 | 0.034 | 2.502 | −0.563, 5.567 | 0.110 | 1.505 | −1.511, 4.521 | 0.328 | |||

| Senior high school | 3.510 | 0.101, 6.920 | 0.044 | 2.272 | −0.897, 5.442 | 0.160 | 1.228 | −1.890, 4.347 | 0.440 | |||

| College or higher | 4.649 | 1.074, 8.223 | 0.011 | 2.973 | −0.351, 6.296 | 0.080 | 1.733 | −1.541, 5.007 | 0.300 | |||

| Mother educational attainment | ||||||||||||

| Junior high school | 3.965 | 1.487, 6.442 | 0.002 | 2.562 | 0.258, 4.866 | 0.029 | 2.114 | −0.154, 4.382 | 0.068 | |||

| Senior high school | 5.447 | 2.819, 8.075 | <0.001 | 3.799 | 1.355, 6.243 | 0.002 | 3.298 | 0.888, 5.707 | 0.007 | |||

| College or higher | 5.132 | 2.320, 7.945 | <0.001 | 2.516 | −0.104, 5.136 | 0.060 | 1.971 | −0.617, 4.558 | 0.135 | |||

| Family cohesion | 0.612 | 0.569, 0.655 | <0.001 | 0.590 | 0.547, 0.632 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Only child | 0.736 | −0.265, 1.738 | 0.150 | |||||||||

| Family economic status | ||||||||||||

| normal | 6.870 | 4.544, 9.195 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| good | 11.267 | 8.924, 13.609 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Region | −2.561 | −3.540, −1.583 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Areas | −0.908 | −1.890, 0.073 | 0.070 | |||||||||

| β | SE | LICI | ULCI | |

| Total Effect | ||||

| Fathers’ healthy behaviors→Proactive health behaviors | 1.090 | 0.103 | 0.889 | 1.291 |

| Mothers’ healthy behaviors→Proactive health behaviors | 0.845 | 0.110 | 0.629 | 1.061 |

| β | SE | LICI | ULCI | |

| Direct Effect | ||||

| Fathers’ healthy behaviors→Proactive health behaviors | 0.553 | 0.092 | 0.373 | 0.734 |

| Mothers’ healthy behaviors→Proactive health behaviors | 0.498 | 0.098 | 0.305 | 0.690 |

| Self-efficacy→Proactive health behaviors | 0.383 | 0.036 | 0.313 | 0.453 |

| Family cohesion→Proactive health behaviors | 0.623 | 0.022 | 0.581 | 0.666 |

| Fathers’ healthy behaviors→Self-efficacy | 0.250 | 0.039 | 0.173 | 0.326 |

| Mothers’ healthy behaviors→Self-efficacy | 0.264 | 0.042 | 0.181 | 0.346 |

| Fathers’ healthy behaviors→Family cohesion | 0.707 | 0.064 | 0.582 | 0.833 |

| Mothers’ healthy behaviors→Family cohesion | 0.395 | 0.069 | 0.260 | 0.530 |

| β | Boot SE | Boot LICI | Boot ULCI | |

| Indirect Effect | ||||

| Fathers’ healthy behaviors→Self-efficacy→Proactive health behaviors | 0.096 | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.027 |

| Fathers’ healthy behaviors→Family cohesion→Proactive health behaviors | 0.441 | 0.008 | 0.070 | 0.105 |

| Mothers’ healthy behaviors→Self-efficacy→Proactive health behaviors | 0.101 | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.027 |

| Mothers’ healthy behaviors→Family cohesion→Proactive health behaviors | 0.246 | 0.008 | 0.031 | 0.061 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, T.; Zhou, J.; Yu, L.; Li, S.; Leong, Q.N.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Y. Intergenerational Transmission of Proactive Health Behaviors Among Adolescents with Overweight or Obesity: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy and Family Cohesion. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213377

Hu T, Zhou J, Yu L, Li S, Leong QN, Li J, Zhou Y, Jiang Y. Intergenerational Transmission of Proactive Health Behaviors Among Adolescents with Overweight or Obesity: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy and Family Cohesion. Nutrients. 2025; 17(21):3377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213377

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Tian, Jingwei Zhou, Lianlong Yu, Suyun Li, Qian Ning Leong, Jingjing Li, Yunping Zhou, and Ying Jiang. 2025. "Intergenerational Transmission of Proactive Health Behaviors Among Adolescents with Overweight or Obesity: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy and Family Cohesion" Nutrients 17, no. 21: 3377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213377

APA StyleHu, T., Zhou, J., Yu, L., Li, S., Leong, Q. N., Li, J., Zhou, Y., & Jiang, Y. (2025). Intergenerational Transmission of Proactive Health Behaviors Among Adolescents with Overweight or Obesity: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy and Family Cohesion. Nutrients, 17(21), 3377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213377