Mediterranean and MIND Dietary Patterns and Cognitive Performance in Multiple Sclerosis: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the UK Multiple Sclerosis Register

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Demographics and Clinical Outcomes

2.3. Diet

2.4. Cognitive Outcome Measure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. Primary Analyses

2.5.2. Subgroup Analyses

2.5.3. Sensitivity Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Characteristics of Cognitive Performance Scores

3.3. Overall Associations Between Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Cognitive Performance

3.4. Overall Associations Between MIND Diet Adherence and Cognitive Performance

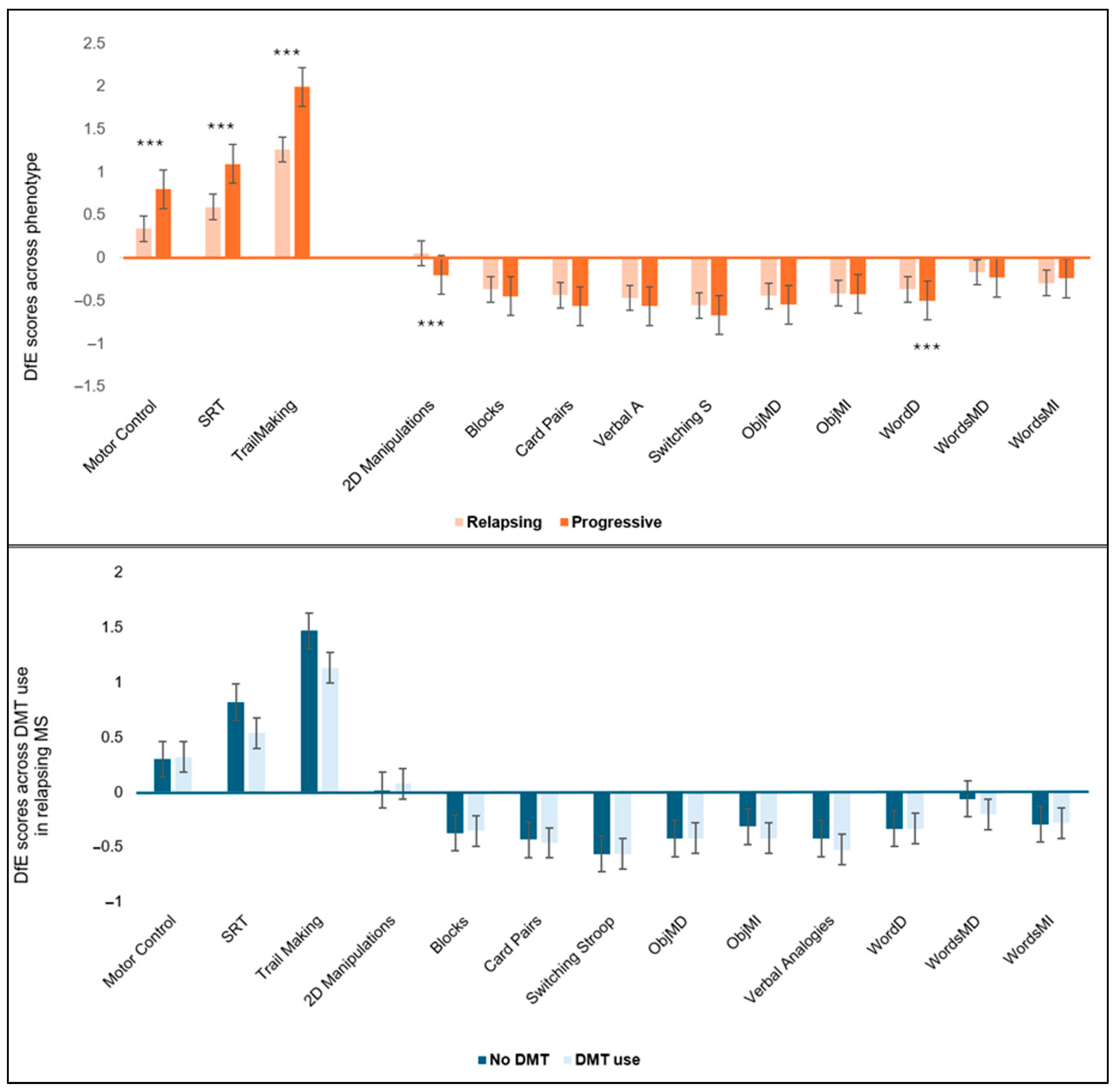

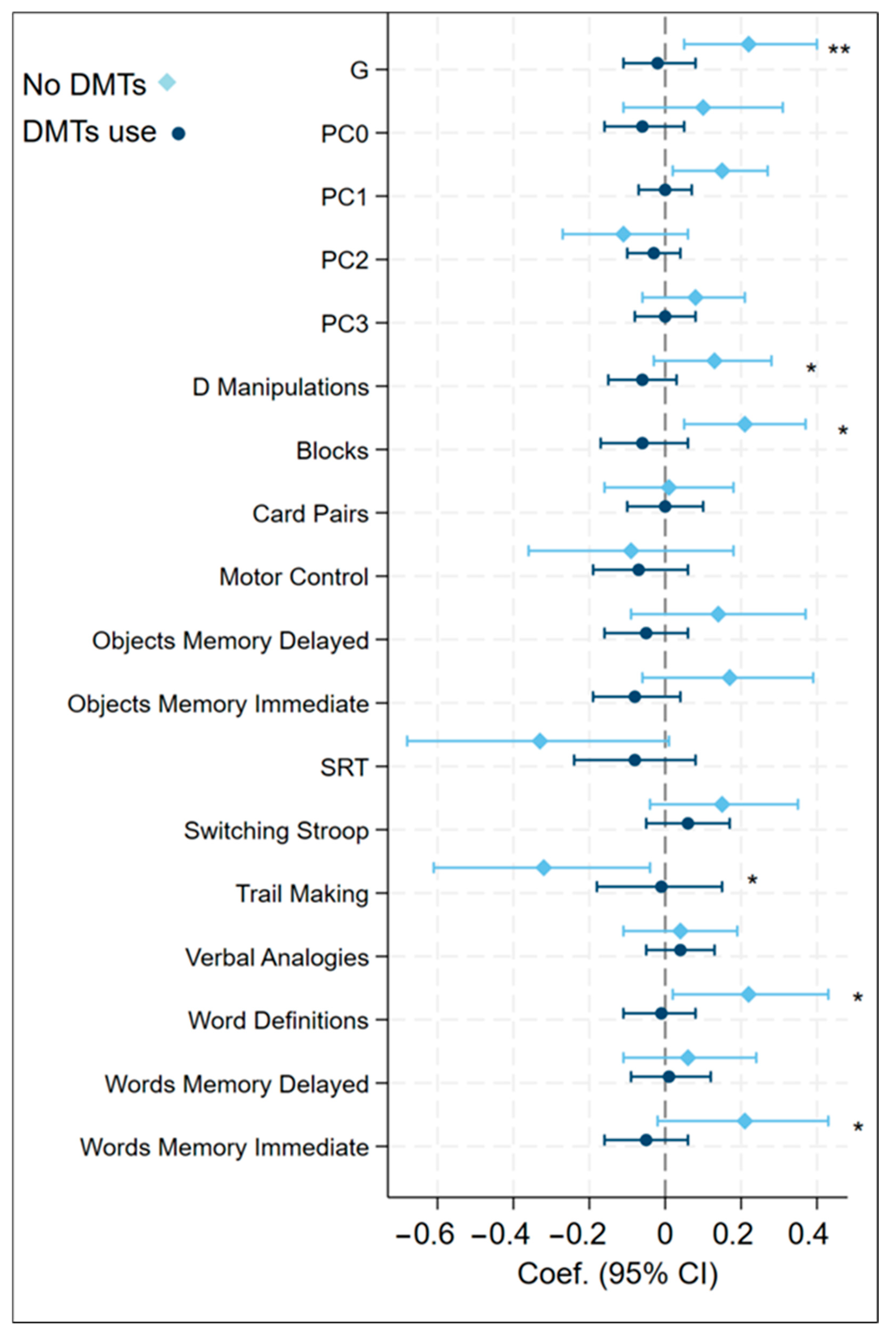

3.5. Subgroup Analysis of Associations Between aMED Diet Scores and Cognitive Function by MS Phenotype and DMT Usage

3.6. Subgroup Analysis of Associations Between MIND Diet Scores and Cognitive Function by MS Phenotype and DMT Usage

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Group Differences

4.3. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aMED | Alternative Mediterranean |

| aMED | Adjusted Mediterranean diet |

| DfE | Deviation from Expected (adjusted cognitive scores standardised using the control SD to reflect the number of SDs above or below the expected score for someone with similar sociodemographic characteristics who completed the assessment on a similar device) |

| DMT | Disease modifying therapy |

| IPS | Information processing speed |

| M | Mean |

| MIND | Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay |

| MS | Multiple sclerosis |

| ObjMD | Objects Memory Delayed |

| ObjMI | Objects Memory Immediate |

| PC0 | Object memory |

| PC1 | Problem solving |

| PC2 | Information processing speed |

| PC3 | Words memory |

| PhD | Doctor of Philosophy |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| Switching S | Switching Stroop |

| SRT | Simple Reaction Time |

| Verbal A | Verbal Analogies |

| WordD | Word definition |

| WordsMD | Words Memory Delayed |

| WordsMI | Words Memory Immediate |

References

- Walton, C.; King, R.; Rechtman, L.; Kaye, W.; Leray, E.; Marrie, R.A.; Robertson, N.; La Rocca, N.; Uitdehaag, B.; van der Mei, I.; et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult. Scler. 2020, 26, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapica-Topczewska, K.; Kułakowska, A.; Kochanowicz, J.; Brola, W. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: Global trends, regional differences, and clinical implications. Neurol. I Neurochir. Pol. 2025, 59, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassmann, H. Multiple sclerosis pathology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a028936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, M.T.; Culpepper, W.J.; Nichols, E.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Gebrehiwot, T.T.; Hay, S.I.; Feigin, V.L.; Vos, T.; Murray, C.J.L.; Naghavi, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.D. Domains of cognition and their assessment. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 21, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Filippo, M.; Portaccio, E.; Mancini, A.; Calabresi, P. Multiple sclerosis and cognition: Synaptic failure and network dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruet, A.; Deloire, M.; Charre-Morin, J.; Hamel, D.; Brochet, B. Cognitive impairment differs between primary progressive and relapsing-remitting MS. Neurology 2013, 80, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Benito-León, J.; González, J.-M.M.; Rivera-Navarro, J. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: Integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet Neurol. 2005, 4, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiaravalloti, N.D.; DeLuca, J. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, J.; Chiaravalloti, N.D.; Sandroff, B.M. Treatment and management of cognitive dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 16, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalb, R.; Beier, M.; Benedict, R.H.B.; Charvet, L.; Costello, K.; Feinstein, A.; Gingold, J.; Goverover, Y.; Halper, J.; Harris, C.; et al. Recommendations for cognitive screening and management in multiple sclerosis care. Mult. Scler. 2018, 24, 1665–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landmeyer, N.C.; Bürkner, P.-C.; Wiendl, H.; Ruck, T.; Hartung, H.-P.; Holling, H.; Meuth, S.G.; Johnen, A. Disease-modifying treatments and cognition in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis. Neurology 2020, 94, e2373–e2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, H.J.; Watson, C. Characteristics, burden of illness, and physical functioning of patients with relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: A cross-sectional US survey. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017, 13, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooney, S.; Wood, L.; Moffat, F.; Paul, L. Prevalence of fatigue and its association with clinical features in progressive and non-progressive forms of Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2019, 28, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Becker, H.; Stuifbergen, A. Comparing Health Promotion and Quality of Life in People with Progressive Versus Nonprogressive Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. MS Care 2020, 22, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankespoor, R.J.; Schellekens, M.P.; Vos, S.H.; Speckens, A.E.; de Jong, B.A. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction on psychological distress and cognitive functioning in patients with multiple sclerosis: A pilot study. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesser, B.S.; Rapozo, M.; Glatt, R.; Patis, C.; Panos, S.; Merrill, D.A.; Siddarth, P. Lifestyle intervention improves cognition and quality of life in persons with early Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 91, 105897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; You, Q.; Hou, X.; Zhang, S.; Du, L.; Lv, Y.; Yu, L. The effect of exercise on cognitive function in people with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 2908–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryfonos, C.; Pavlidou, E.; Vorvolakos, T.; Alexatou, O.; Vadikolias, K.; Mentzelou, M.; Tsourouflis, G.; Serdari, A.; Antasouras, G.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; et al. Association of higher mediterranean diet adherence with lower prevalence of disability and symptom severity, depression, anxiety, stress, sleep quality, cognitive impairment, and physical inactivity in older adults with multiple sclerosis. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2023, 37, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz Sand, I. The Role of Diet in Multiple Sclerosis: Mechanistic Connections and Current Evidence. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2018, 7, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zonneveld, S.M.; van den Oever, E.J.; Haarman, B.C.M.; Grandjean, E.L.; Nuninga, J.O.; van de Rest, O.; Sommer, I.E.C. An anti-inflammatory diet and its potential benefit for individuals with mental disorders and neurodegenerative diseases—A narrative review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz Sand, I.; Levy, S.; Fitzgerald, K.; Sorets, T.; Sumowski, J.F. Mediterranean diet is linked to less objective disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2023, 29, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Kyrozis, A.; Rossi, M.; Katsoulis, M.; Trichopoulos, D.; La Vecchia, C.; Lagiou, P. Mediterranean diet and cognitive decline over time in an elderly Mediterranean population. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 1311–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, C.T.; Guyer, H.; Langa, K.M.; Yaffe, K. Neuroprotective Diets Are Associated with Better Cognitive Function: The Health and Retirement Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 1857–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohlouli, J.; Namjoo, I.; Borzoo-Isfahani, M.; Poorbaferani, F.; Moravejolahkami, A.R.; Clark, C.C.T.; Hojjati Kermani, M.A. Modified Mediterranean diet v. traditional Iranian diet: Efficacy of dietary interventions on dietary inflammatory index score, fatigue severity and disability in multiple sclerosis patients. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razeghi-Jahromi, S.; Doosti, R.; Ghorbani, Z.; Saeedi, R.; Abolhasani, M.; Akbari, N.; Cheraghi-Serkani, F.; Moghadasi, A.N.; Azimi, A.; Togha, M.; et al. A randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of a mediterranean-like diet in patients with multiple sclerosis-associated cognitive impairments and fatigue. Curr. J. Neurol. 2020, 19, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravejolahkami, A.R.; Paknahad, Z.; Chitsaz, A. Association of dietary patterns with systemic inflammation, quality of life, disease severity, relapse rate, severity of fatigue and anthropometric measurements in MS patients. Nutr. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.C.; Tangney, C.C.; Wang, Y.; Sacks, F.M.; Bennett, D.A.; Aggarwal, N.T. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015, 11, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, R.P.; Blair, J.; Shatz, R.; Manly, J.J.; Judd, S.E. Association of adherence to a MIND-style diet with the risk of cognitive impairment and decline in the REGARDS cohort. Neurology 2024, 103, e209817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devore, E.E.; Kang, J.H.; Breteler, M.M.B.; Grodstein, F. Dietary intakes of berries and flavonoids in relation to cognitive decline. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 72, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sand, I.B.K.; Fitzgerald, K.C.; Gu, Y.; Brandstadter, R.; Riley, C.S.; Buyukturkoglu, K.; Leavitt, V.M.; Krieger, S.; Miller, A.; Lublin, F.; et al. Dietary factors and MRI metrics in early Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2021, 53, 103031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, L.; Wang, Y.; Fakuda, K.; Leurgans, S.; Aggarwal, N.; Morris, M. Mediterranean-Dash Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet slows cognitive decline after stroke. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 6, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe-Roach, A.; Yu, A.C.; Golz, E.; Sundvick, K.; Cirstea, M.S.; Kliger, D.; Foulger, L.H.; Mackenzie, M.; Finlay, B.B.; Appel-Cresswell, S. MIND and Mediterranean diets associated with later onset of Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2021, 36, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, L.L.; Dhana, K.; Liu, X.; Carey, V.; Ventrelle, J.; Johnson, K.; Hollings, C.; Bishop, L.; Laranjo, N.; Stubbs, B.; et al. Trial of the MIND diet for prevention of cognitive decline in older persons. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, R.M.; Rodgers, W.J.; Chataway, J.; Schmierer, K.; Akbari, A.; Tuite-Dalton, K.; Lockhart-Jones, H.; Griffiths, D.; Noble, D.J.; Jones, K.H.; et al. Validating the portal population of the United Kingdom Multiple Sclerosis Register. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2018, 24, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerede, A.; Moura, A.; Giunchiglia, V.; Carta, E.; Trender, W.; Tuite-Dalton, K.; Witts, J.; Craig, E.; Knowles, S.; Rodgers, J.; et al. Large-scale online assessment uncovers a distinct Multiple Sclerosis subtype with selective cognitive impairment. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, S.A.; Welch, A.A.; McTaggart, A.; Mulligan, A.A.; Runswick, S.A.; Luben, R.; Oakes, S.; Khaw, K.T.; Day, N.E. Nutritional methods in the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer in Norfolk. Public Health Nutr. 2001, 4, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.T.; McCullough, M.L.; Newby, P.K.; Manson, J.E.; Meigs, J.B.; Rifai, N.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Diet-quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Kouris-Blazos, A.; Wahlqvist, M.L.; Gnardellis, C.; Lagiou, P.; Polychronopoulos, E.; Vassilakou, T.; Lipworth, L.; Trichopoulos, D. Diet and overall survival in elderly people. BMJ 1995, 311, 1457–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrou, P.N.; Kipnis, V.; Thiébaut, A.C.M.; Reedy, J.; Subar, A.F.; Wirfält, E.; Flood, A.; Mouw, T.; Hollenbeck, A.R.; Leitzmann, M.F.; et al. Mediterranean dietary pattern and prediction of all-cause mortality in a US population: Results from the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 2461–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazahery, H.; Daly, A.; Pham, N.M.; Stephens, M.; Dunlop, E.; Ponsonby, A.-L.; Ausimmune/AusLong Investigator Group; Black, L.J. Higher Mediterranean diet score is associated with longer time between relapses in Australian females with multiple sclerosis. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.01042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, M.B.E.; Black, A.E. Markers of the validity of reported energy intake. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 895S–920S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson-Yap, S.; Neate, S.L.; Nag, N.; Probst, Y.C.; Yu, M.; Jelinek, G.A.; Reece, J.C. Longitudinal associations between quality of diet and disability over 7.5 years in an international sample of people with multiple sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2023, 30, 3200–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loonstra, F.C.; de Ruiter, D.; Schoonheim, M.M.; Moraal, B.; Strijbis, E.M.M.; de Jong, B.A.; Uitdehaag, B.M.J. The role of diet in multiple sclerosis onset and course: Results from a nationwide retrospective birth-year cohort. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2023, 10, 1268–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breusch, T.S.; Pagan, A.R. A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica 1979, 47, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Multiple significance tests: The Bonferroni method. BMJ 1995, 310, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longley, W.A.; Honan, C. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: The role of the general practitioner in cognitive screening and care coordination. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2022, 51, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, S.J.; Kosmidis, S.E.; Korompoki, A.; Alexopoulos, A.; Mantaiou, A.; Jeorgakopoulos, S.; Kanellou, S.; Tzaferou, V.; Fountoulakis, K.N.; Karoutzouglou, V.; et al. Dietary Intake, Mediterranean and Nordic Diet Adherence in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, C.; Parks, S.; Titcomb, T.J.; Arthofer, A.; Meirick, P.; Grogan, N.; Ehlinger, M.A.; Bisht, B.; Fox, S.S.; Daack-Hirsch, S.; et al. Facilitators of and Barriers to Adherence to Dietary Interventions Perceived by Women with Multiple Sclerosis and Their Support Persons. Int. J. MS Care 2022, 24, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjmand, G.; Abbas-Zadeh, M.; Eftekhari, M.H. Effect of MIND diet intervention on cognitive performance and brain structure in healthy obese women: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, A.M.; Kang, J.H.; Feskens, E.J.M.; de Groot, C.P.G.M.; Grodstein, F.; van de Rest, O. Association of long-term adherence to the mind diet with cognitive function and cognitive decline in American women. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Matheis, R.J.; Schoenberger, N.E.; Shiflett, S.C. Use of unconventional therapies by individuals with multiple sclerosis. Clin. Rehabil. 2003, 17, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sippel, A.; Riemann-Lorenz, K.; Scheiderbauer, J.; Kleiter, I.; Morrison, R.; Kofahl, C.; Heesen, C. Patients experiences with multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapies in daily life–a qualitative interview study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zameer, U.; Tariq, A.; Asif, F.; Kamran, A. Empowering minds and bodies: The impact of exercise on multiple sclerosis and cognitive health. Ann. Neurosci. 2024, 31, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letenneur, L.; Proust-Lima, C.; Le Gouge, A.; Dartigues, J.-F.; Barberger-Gateau, P. Flavonoid intake and cognitive decline over a 10-year period. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 165, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheirouri, S.; Alizadeh, M. MIND diet and cognitive performance in older adults: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 8059–8077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manca, R.; Sharrack, B.; Paling, D.; Wilkinson, I.D.; Venneri, A. Brain connectivity and cognitive processing speed in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. J. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 388, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.S.; Rampelli, S.; Jeffery, I.B.; Santoro, A.; Neto, M.; Capri, M.; Giampieri, E.; Jennings, A.; Candela, M.; Turroni, S.; et al. Mediterranean diet intervention alters the gut microbiome in older people reducing frailty and improving health status: The NU-AGE 1-year dietary intervention across five European countries. Gut 2020, 69, 1218–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, N.; Yu, M.; Jelinek, G.A.; Simpson-Yap, S.; Neate, S.L.; Schmidt, H.K. Associations between lifestyle behaviors and quality of life differ based on multiple sclerosis phenotype. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, S.; Tektonidis, T.G.; Coverdale, C.; Penny, S.; Collett, J.; Chu, B.T.; Izadi, H.; Middleton, R.; Dawes, H. A cross sectional assessment of nutrient intake and the association of the inflammatory properties of nutrients and foods with symptom severity in a large cohort from the UK Multiple Sclerosis Registry. Nutr. Res. 2021, 85, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, J.; Friede, T.; Vonberg, F.W.; Constantinescu, C.S.; Coles, A.; Chataway, J.; Duddy, M.; Emsley, H.; Ford, H.; Fisniku, L.; et al. The impact of smoking cessation on multiple sclerosis disease progression. Brain Behav. 2022, 145, 1368–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulligan, A.A.; Luben, R.N.; Bhaniani, A.; Parry-Smith, D.J.; O’Connor, L.; Khawaja, A.P.; Forouhi, N.G.; Khaw, K.T. A new tool for converting food frequency questionnaire data into nutrient and food group values: FETA research methods and availability. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Sun, D. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of developing cognitive disorders: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrezova, E.; Stefler, D.; Capkova, N.; Vaclova, H.; Bobak, M.; Pikhart, H. Mediterranean diet score linked to cognitive functioning in Czech women: A cross-sectional population-based study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2025, 64, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacentini, C.; Argento, O.; Nocentini, U. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: “classic” knowledge and recent acquisitions. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2023, 81, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cognitive Domains | Cognitive Task | Cognitive Domain Measured | Task Description | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G factor | All | General intelligence | Aggregate score representing overall cognitive performance across all tasks. | Accuracy |

| P0: Objects memory | Objects Memory Immediate | Short-term visual recognition memory | Identify target object from distractors immediately after viewing a series of object silhouettes. | Accuracy |

| Objects Memory Delayed | Medium-term visual recognition memory | Recall previously seen objects after a delay without being reminded of them. | Accuracy | |

| P1: Problem solving | 2D Manipulations | 2D spatial reasoning | Match a rotated grid of coloured squares with the correct unaltered version. | Accuracy |

| Blocks | 2D spatial planning | Remove blocks to match a target configuration in a gravity-affected grid. | Accuracy | |

| Card Pairs | Associative working memory | Match pairs of cards after they have been turned over from memory. | Accuracy | |

| Switching Stroop | Attentional control and cognitive flexibility | Respond based on changing conditions of text or ink colour under rule-switching. | Accuracy | |

| Verbal Analogies | Grammar-based verbal reasoning | Evaluate the correctness of analogy statements based on grammar and logic. | Accuracy | |

| Word Definitions | Crystallised verbal knowledge | Choose the correct definition for a series of English words from multiple choices. | Accuracy | |

| P2: Information processing speed | SRT | Simple reaction time | Click on the screen as soon as a visual target appears. | Latency |

| Motor Control | Visuomotor abilities | Click on targets that appear across the screen as quickly and accurately as possible. | Latency | |

| Trail Making | Cognitive flexibility and visual attention | Click on tiles in numerical and alphabetical order, alternating between them. | Latency | |

| P3: Words memory | Words Memory Immediate | Short-term verbal recognition memory | Identify previously seen words from a new list immediately after initial exposure. | Accuracy |

| Words Memory Delayed | Medium-term verbal recognition memory | Identify previously seen words from a new list after a delay. | Accuracy |

| Demographics | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total N | 967 | |

| Age (M, SD) | 56.47 (10.86) | |

| MS duration (M, SD) | 18.8 (11.67) | |

| Gender | Female | 766 (79.2) |

| Male | 201 (20.8) | |

| Ethnicity a | White | 942 (97.4) |

| Asian or Asian British | 8 (0.8) | |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 5 (0.5) | |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic groups | 8 (0.8) | |

| Other | 4 (0.4) | |

| Dominant hand | Right | 831 (85.9) |

| Left | 105 (10.9) | |

| Ambidextrous | 31 (3.2) | |

| First language | English | 937 (96.9) |

| Other | 30 (3.1) | |

| Residence | United Kingdom | 963 (99.6) |

| Abroad | 4 (0.4) | |

| Education | Pre-General Certificate of Secondary Education | 22 (2.3) |

| School | 439 (45.4) | |

| Degree | 473 (48.9) | |

| PhD | 33 (3.4) | |

| Occupation | Worker | 347 (35.9) |

| Retired | 399 (41.3) | |

| Disabled/Not applicable/Sheltered employment | 163 (16.9) | |

| Homemaker | 41 (4.2) | |

| Unemployed/Looking for work | 12 (1.2) | |

| Student | 3 (0.3) | |

| Unknown | 2 (0.2) | |

| MS phenotype | Benign | 30 (3.0) |

| RRMS | 514 (51.8) | |

| PPMS | 159 (16.0) | |

| SPMS | 233 (23.5) | |

| Transitioning to SPMS | 27 (2.7) | |

| Unknown | 30 (3.0) | |

| DMT use | Yes | 401 (51.4) |

| No | 379 (48.6) | |

| aMED diet score (M, SD) | 4.20 (1.99) | |

| MIND diet score (M, SD) | 7.85 (1.67) |

| Total aMED (0–9) | Categorical aMED | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2: aMED (4–5) | T3: aMED (6–9) | ||||||

| Domain | Test | β (95% CIs) | p | β (95% CIs) | p | β (95% CIs) | p |

| G factor | 0.04 [−0.03, 0.10] | 0.278 | 0.03 [−0.13, 0.19] | 0.742 | 0.08 [−0.08, 0.25] | 0.315 | |

| PC0: Object memory | −0.05 [−0.12, 0.02] | 0.174 | −0.14 [−0.30, 0.03] | 0.103 | −0.12 [−0.30, 0.05] | 0.169 | |

| Objects In Memory Delayed | −0.04 [−0.12, 0.03] | 0.271 | −0.13 [−0.31, 0.05] | 0.259 | −0.06 [−0.26, 0.13] | 0.526 | |

| Objects Memory Immediate | −0.04 [−0.12, 0.04] | 0.333 | −0.13 [−0.31, 0.05] | 0.155 | −0.11 [−0.31, 0.08] | 0.304 | |

| PC1: Problem solving | 0.02 [−0.04, 0.07] | 0.549 | −0.03 [−0.17, 0.10] | 0.642 | 0.03 [−0.11, 0.18] | 0.678 | |

| 2D Manipulations | −0.02 [−0.09, 0.05] | 0.566 | 0.03 [−0.14, 0.19] | 0.761 | −0.07 [−0.25, 0.10] | 0.427 | |

| Blocks | 0.04 [−0.05, 0.12] | 0.336 | −0.15 [−0.34, 0.04] | 0.123 | −0.06 [−0.27, 0.14] | 0.546 | |

| Card Pairs | −0.02 [−0.09, 0.05] | 0.549 | −0.04 [−0.21, 0.14] | 0.676 | −0.05 [−0.24, 0.14] | 0.599 | |

| Switching Stroop | −0.02 [−0.05, 0.10] | 0.535 | −0.13 [−0.32, 0.06] | 0.180 | 0.10 [−0.11, 0.30] | 0.352 | |

| Verbal Analogies | 0.07 [0.01, 0.13] | 0.025 | 0.25 [0.011, 0.39] | <0.001 † | 0.09 [−0.06, 0.25] | 0.219 | |

| Word Definitions | 0.08 [0.01, 0.15] | 0.017 | 0.04 [−0.13, 0.20] | 0.673 | 0.19 [0.03, 0.36] | 0.023 | |

| PC2: IPS | −0.07 [−0.13, −0.01] | 0.013 | −0.20 [−0.33, −0.07] | 0.005 † | 0.13 [−0.02, 0.27] | 0.089 | |

| SRT | −0.13 [−0.25, −0.00] | 0.045 | −0.17 [−0.45, 0.11] | 0.243 | −0.24 [−0.55, 0.06] | 0.112 | |

| Motor Control | −0.12 [−0.23, −0.02] | 0.020 | −0.20 [−0.44, 0.04] | 0.101 | −0.22 [−0.45, 0.02] | 0.069 | |

| Trail Making | −0.12 [−0.25, 0.01] | 0.068 | −0.39 [−0.72, −0.06] | 0.020 | −0.25 [−0.61, 0.12] | 0.183 | |

| PC3: Words memory | 0.04 [−0.02, 0.10] | 0.240 | −0.03 [−0.18, 0.11] | 0.664 | 0.08 [−0.07, 0.23] | 0.304 | |

| Words Memory Immediate | 0.06 [−0.03, 0.14] | 0.192 | 0.13 [−0.06, 0.33] | 0.179 | 0.15 [−0.06, 0.36] | 0.165 | |

| Words Memory Delays | 0.04 [−0.04, 0.12] | 0.299 | 0.10 [−0.09, 0.30] | 0.303 | 0.07 [−0.13, 0.28] | 0.495 | |

| Total MIND | Categorical MIND | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2: MIND (4–5) | T3: MIND (6–9) | ||||||

| Domain | Subtest | β (95% CIs) | p | β (95% CIs) | p | β (95% CIs) | p |

| G factor | 0.07 [−0.01, 0.13] | 0.060 | 0.09 [−0.08, 0.26] | 0.298 | 0.13 [−0.04, 0.30] | 0.145 | |

| PC0: Object memory | 0.01 [−0.06, 0.08] | 0.779 | 0.01 [−0.16, 0.18] | 0.895 | −0.03 [−0.21, 0.16] | 0.788 | |

| Objects Memory Delayed | 0.04 [−0.04, 0.12] | 0.376 | 0.05 [−0.14, 0.24] | 0.606 | 0.03 [−0.17, 0.23] | 0.770 | |

| Objects Memory Immediate | 0.01 [−0.07, 0.10] | 0.748 | 0.03 [−0.16, 0.21] | 0.774 | −0.02 [−0.21, 0.18] | 0.878 | |

| PC1: Problem solving | 0.04 [−0.02, 0.09] | 0.197 | −0.03 [−0.17, 0.10] | 0.623 | 0.08 [−0.06, 0.22] | 0.243 | |

| 2D Manipulations | 0.01 [−0.07, 0.08] | 0.939 | 0.07 [−0.10, 0.24] | 0.430 | 0.04 [−0.13, 0.21] | 0.622 | |

| Blocks | 0.01 [−0.07, 0.09] | 0.726 | −0.02 [−0.21, 0.17] | 0.831 | 0.03 [−0.17, 0.24] | 0.748 | |

| Card Pairs | 0.03 [−0.04, 0.10] | 0.428 | 0.07 [−0.10, 0.24] | 0.439 | 0.04 [−0.13, 0.21] | 0.682 | |

| Switching Stroop | 0.06 [−0.02, 0.14] | 0.121 | −0.10 [−0.29, 0.05] | 0.303 | −0.11 [−0.30, 0.09] | 0.273 | |

| Verbal Analogies | 0.03 [−0.03, 0.09] | 0.354 | 0.07 [−0.08, 0.21] | 0.364 | 0.01 [−0.14, 0.16] | 0.927 | |

| Word Definitions | 0.09 [0.02, 0.15] | 0.009 † | 0.06 [−0.11, 0.23] | 0.500 | 0.21 [0.04, 0.38] | 0.015 | |

| PC2: IPS | −0.05 [−0.10, 0.01] | 0.104 | −0.15 [−0.28, −0.01] | 0.032 | −0.13 [−0.27, −0.01] | 0.064 | |

| SRT | −0.13 [−0.25, −0.01] | 0.031 | −0.31 [−0.59, −0.02] | 0.029 | −0.38 [−0.67, −0.10] | 0.014 † | |

| Motor Control | −0.08 [−0.18, 0.01] | 0.084 | −0.23 [−0.47, 0.00] | 0.065 | −0.20 [−0.46, 0.06] | 0.135 | |

| Trail Making | −0.10 [−0.24, 0.04] | 0.164 | −0.30 [−0.64, 0.06] | 0.088 | −0.27 [−0.62, 0.08] | 0.134 | |

| PC3: Words memory | 0.06 [0.01, 0.12] | 0.037 | 0.17 [0.02, 0.31] | 0.016 | 0.11 [−0.03, 0.26] | 0.125 | |

| Words Memory Immediate | 0.07 [0.00, 0.16] | 0.074 | 0.20 [0.01, 0.39] | 0.037 | 0.11 [−0.09, 0.31] | 0.266 | |

| Words Memory Delays | 0.07 [0.01, 0.15] | 0.070 | 0.21 [0.02, 0.41] | 0.031 | 0.15 [−0.04, 0.35] | 0.127 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, M.; Simpson-Yap, S.; Lerede, A.; Nicholas, R.; Coe, S.; Tektonidis, T.G.; Solsona, E.M.; Middleton, R.; Probst, Y.; Hampshire, A.; et al. Mediterranean and MIND Dietary Patterns and Cognitive Performance in Multiple Sclerosis: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the UK Multiple Sclerosis Register. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3326. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213326

Yu M, Simpson-Yap S, Lerede A, Nicholas R, Coe S, Tektonidis TG, Solsona EM, Middleton R, Probst Y, Hampshire A, et al. Mediterranean and MIND Dietary Patterns and Cognitive Performance in Multiple Sclerosis: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the UK Multiple Sclerosis Register. Nutrients. 2025; 17(21):3326. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213326

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Maggie, Steve Simpson-Yap, Annalaura Lerede, Richard Nicholas, Shelly Coe, Thanasis G. Tektonidis, Eduard Martinez Solsona, Rod Middleton, Yasmine Probst, Adam Hampshire, and et al. 2025. "Mediterranean and MIND Dietary Patterns and Cognitive Performance in Multiple Sclerosis: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the UK Multiple Sclerosis Register" Nutrients 17, no. 21: 3326. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213326

APA StyleYu, M., Simpson-Yap, S., Lerede, A., Nicholas, R., Coe, S., Tektonidis, T. G., Solsona, E. M., Middleton, R., Probst, Y., Hampshire, A., Milanzi, E., Cui, G., Davenport, R. A., Neate, S., Pisano, M., Kirkland, H., & Reece, J. (2025). Mediterranean and MIND Dietary Patterns and Cognitive Performance in Multiple Sclerosis: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the UK Multiple Sclerosis Register. Nutrients, 17(21), 3326. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213326