An Asset-Based Examination of Contextual Factors Influencing Nutrition Security: The Case of Rural Northern New England

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

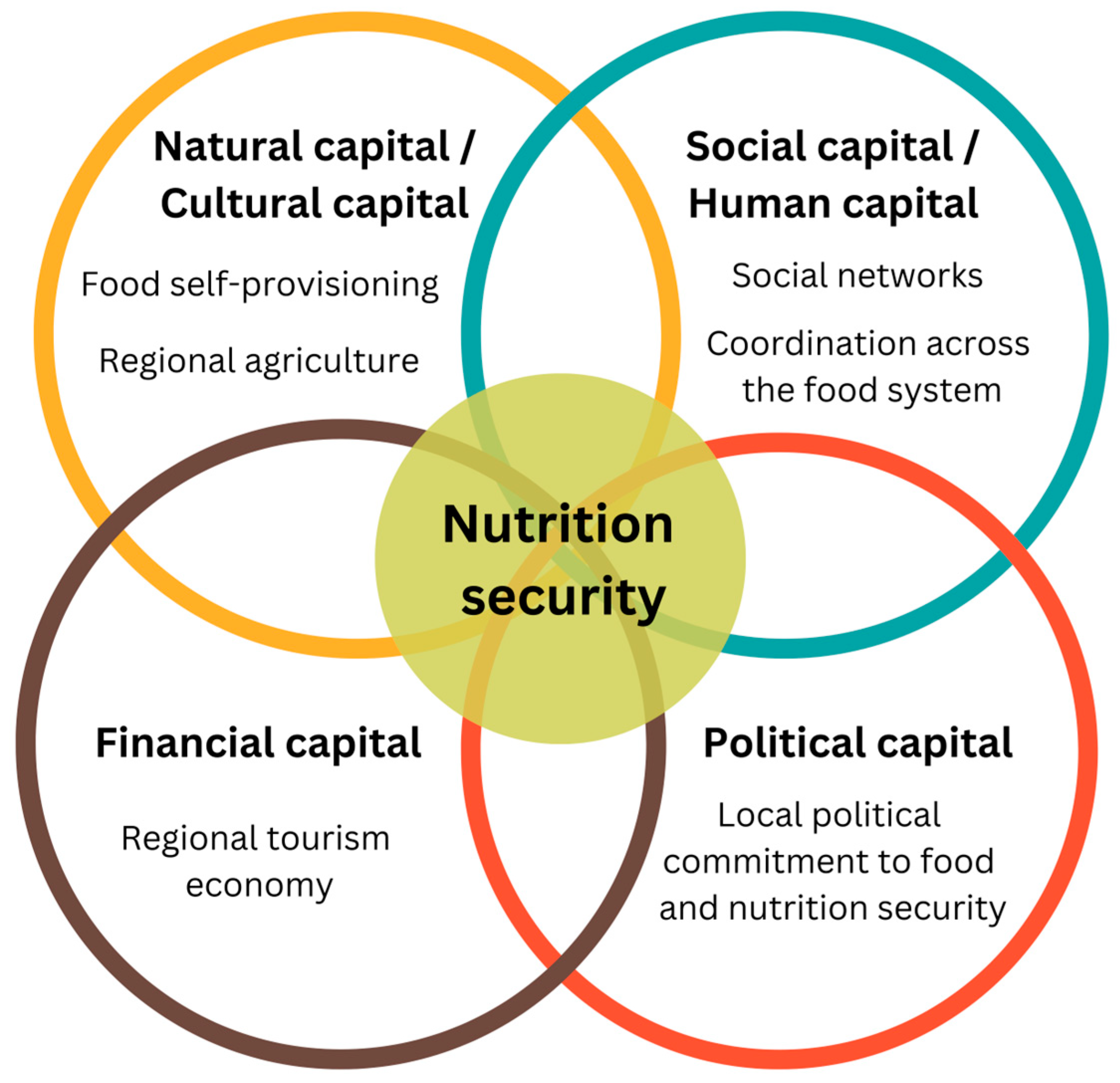

3.1. Rural Assets Identified by Food System Experts

“I just think that there can be areas that are… ‘economically poor’ by these capitalistic defined standards that might be very, very rich in other ways that aren’t defined, that aren’t measured, that aren’t given room in the conversation, aren’t given room in like policymaking conversations.”Food hub staff member, Vermont.

“I hope if anything gets taken away from my interview and I hope others are saying the same thing, too, is that… nutritious food is so much more than the macro-, micro-… nutrients and calories that are in the food and whether it’s in the grocery store or not. And rural diets consist of so much more that is often left untracked that I would imagine lead to a way more nutritious diet than is given credit for.”Food systems network staff member, Vermont.

3.2. Natural Capital/Cultural Capital

“We have a lot of folks who are more likely to have their own gardens, raise their own chickens or meat, or go hunting. So, there’s a lot more like self-reliance, I would say, on some more… nutritious foods.”Public health/nutrition program staff member, Maine.

“Here in Vermont… we’re very fortunate because we are still an agricultural state and granted there’s barriers but there is, during the growing season, access to a lot of fresh produce which is so incredibly important. And local, meat-based protein and dairy, a lot of dairy.”Extension agent, Vermont.

“You know, there are spatterings of programs like that in rural areas in Maine, whether it’s… community, you know, programs to learn how to forage, learn how to garden… There’s gleaning programs… that get fresh food out of the fields, into food pantries or into school, you know, wherever it is.”Food systems network staff member, Maine.

3.3. Social Capital/Human Capital

“I think that one of the beauties of Maine, too, is that… there really is a sense of community within individual communities and I think there tends to be a lot of taking care of each other. And what I love is, for example, in some communities, you drive down the road and there’s a little stand outside that says ‘free zucchinis’ or, you know, ‘free, help yourself’. I feel like, you know, that is one of the wonderful things about Maine and about… some of the rural aspects… of the state is that people tend to maybe, for example, grow a little more… to provide that support to their neighbors as needed.”Food bank staff member, Maine.

“There’s a bunch of food pantries that communicate with each other. They, you know, they may share food… somebody may throw out like, ‘hey, I’ve got an extra refrigerator. Does anybody need it?”Farm-to-school program staff member, New Hampshire.

3.4. Political Capital

“I’m so grateful that Vermont went to universal school meals for kids because so many families were just, like missing it by literally $5. And, you know, no matter what the school professionals were doing, they just couldn’t, you know… squeeze that peg into that round hole… So, you know, universal school meals is really helpful.”Public health program staff member, Vermont.

“And the Food Access Coalition… much like Hunger Free Vermont, has a lot of partners at the table. They have monthly calls. There’s, you know, all kinds of people that attend that are involved in food and food access from state agencies to nonprofits and Farm to School and Extension, all participate… So, it’s… a network that shares information, we work on policy together…”Farm-to-school program staff member, New Hampshire.

3.5. Financial Capital

“During foliage season in the fall and wintertime, you’ve got more tourists coming through and they’re gonna spend money at the restaurants. They’re gonna tip, you know, tend to give bigger tips to the waiters and waitress staff. So, they’re going to have more money to spend on other things like food and all that.”Health non-profit staff member, Vermont.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Abbreviations

| USDA | U.S. Department of Agriculture |

| NNE | Northern New England |

| CCF | Community Capitals Framework |

| FSP | Food self-provisioning |

| SNAP | Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program |

| WIC | Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children |

| CSA | Community-supported agriculture program |

References

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Security. Available online: https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/general-information/priorities/food-and-nutrition-security (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Food and Nutrition Service. USDA Actions on Nutrition Security; Food and Nutrition Service: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Equitable Systems. Available online: https://www.usda.gov/nutrition-security/equitable-systems (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Anderson, M.D. Beyond Food Security to Realizing Food Rights in the US. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 29, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.A.; Califf, R.M.; Balamurugan, A.; Brown, N.; Benjamin, R.M.; Braund, W.E.; Hipp, J.; Konig, M.; Sanchez, E.; Joynt Maddox, K.E. Call to Action: Rural Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e615–e644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Bolin, J.N.; Brandford, A.; Sanaullah, S.F.; Shrestha, A.; Ory, M.G. The Impact of Diabetes on Rural Americans. In Rural Healthy People 2030; Ferdinand, A.O., Bolin, J.N., Callaghan, T., Rochford, H.I., Lockman, A., Johnson, N.Y., Eds.; Texas A&M University School of Public Health, Southwest Rural Health Research Center: College Station, TX, USA, 2023; pp. 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Samanic, C.M.; Barbour, K.E.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fang, J.; Lu, H.; Schieb, L.; Greenlund, K.J. Prevalence of Self-Reported Hypertension and Antihypertensive Medication Use by County and Rural-Urban Classification—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosby, A.G.; McDoom-Echebiri, M.M.; James, W.; Khandekar, H.; Brown, W.; Hanna, H.L. Growth and Persistence of Place-Based Mortality in the United States: The Rural Mortality Penalty. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, V.; Webb, P.; Micha, R.; Mozaffarian, D. Defining Diet Quality: A Synthesis of Dietary Quality Metrics and Their Validity for the Double Burden of Malnutrition. Lancet Planet Health 2020, 4, e352–e370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbitt, M.P.; Reed-Jones, M.; Hales, L.J.; Burke, M.P. Household Food Security in the United States in 2023 (Report No. ERR-337); USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Seguin-Fowler, R.A.; Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Shanks, C.B.; Babatunde, O.T.; Maddock, J.E. Nutrition and Healthy Eating in Rural America. In Rural Healthy People 2030; Ferdinand, A.O., Bolin, J.N., Callaghan, T., Rochford, H.I., Lockman, A., Johnson, N.Y., Eds.; Texas A&M University School of Public Health, Southwest Rural Health Research Center: College Station, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Belarmino, E.H.; Malacarne, J.; McCarthy, A.C.; Bliss, S.; Laurent, J.; Merrill, S.C.; Niles, M.T.; Nowak, S.; Schattman, R.E.; Yerxa, K. Suboptimal Diets Identified Among Adults in Two Rural States During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2024, 19, 1366–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saksena, M.J.; Okrent, A.M.; Anekwe, T.D.; Cho, C.; Dicken, C.; Effland, A.; Elitzak, H.; Guthrie, J.; Hamrick, K.S.; Hyman, J.; et al. America’s Eating Habits: Food Away From Home, EIB-196; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, L.A.; Meendering, J. Diet and Physical Activity in Rural vs Urban Children and Adolescents in the United States: A Narrative Review. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, C.; Winkler, M.; Houghtaling, B.; Adeyemi, O.; Roehll, A.; Pionke, J.; Anderson Steeves, E. Understanding the Intersection of Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Geographic Location: A Scoping Review of U.S. Consumer Food Purchasing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, W.R.; Sharkey, J.R. Rural and Urban Differences in the Associations between Characteristics of the Community Food Environment and Fruit and Vegetable Intake. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2011, 43, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada-Rojas, L.L.; Ke, Y.; Pyrialakou, V.D.; Gkritza, K. Access to Healthy Food in Urban and Rural Areas: An Empirical Analysis. J. Transp. Health 2021, 23, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinard, C.A.; Byker Shanks, C.; Harden, S.M.; Yaroch, A.L. An Integrative Literature Review of Small Food Store Research across Urban and Rural Communities in the U.S. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Engeda, J.; Moore, L.V.; Auchincloss, A.H.; Moore, K.; Mujahid, M.S. Longitudinal Associations between Objective and Perceived Healthy Food Environment and Diet: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ver Ploeg, M.; Larimore, E.; Wilde, P. The Influence of Food Store Access on Grocery Shopping and Food Spending, EIB-180; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield, K.E.; Hession, S.L.; Weatherspoon, L.; Hoerr, S.L. A Cross-Sectional Analysis Exploring Differences between Food Availability, Food Price, Food Quality and Store Size and Store Location in Flint Michigan. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2020, 15, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, C.; Pelletier, J.; Harnack, L.; Erickson, D.; Lenk, K.; Laska, M. Pricing of Staple Foods at Supermarkets versus Small Food Stores. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kegler, M.C.; Prakash, R.; Hermstad, A.; Anderson, K.; Haardörfer, R.; Raskind, I.G. Food Acquisition Practices, Body Mass Index, and Dietary Outcomes by Level of Rurality. J. Rural Health 2022, 38, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janda, K.M.; Salvo, D.; Ranjit, N.; Hoelscher, D.M.; Nielsen, A.; Lemoine, P.; Casnovsky, J.; van den Berg, A. Who Shops at Their Nearest Grocery Store? A Cross-Sectional Exploration of Disparities in Geographic Food Access among a Low-Income, Racially/Ethnically Diverse Cohort in Central Texas. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2024, 19, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iowa State University Urban Percentage of the Population for States, Historical. Available online: https://www.icip.iastate.edu/tables/population/urban-pct-states (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Lee, S.H.; Moore, L.V.; Park, S.; Harris, D.M.; Blanck, H.M. Adults Meeting Fruit and Vegetable Intake Recommendations—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, J.L.; Kretzmann, J.P. Introduction. In Building Communities from the Inside Out: A Path Toward Finding and Mobilizing a Community’s Assets; ACTA Publications: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Malatzky, C.; Bourke, L. Re-Producing Rural Health: Challenging Dominant Discourses and the Manifestation of Power. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 45, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathie, A.; Cunningham, G. From Clients to Citizens: Asset-Based Community Development as a Strategy for Community-Driven Development. Dev. Pract. 2003, 13, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, N.L.; Desmond, S.M.; Saperstein, S.L.; Billing, A.S.; Gold, R.S.; Tournas-Hardt, A. Assets, Challenges, and the Potential of Technology for Nutrition Education in Rural Communities. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2010, 42, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardison-Moody, A.; Bowen, S.; Bocarro, J.; Schulman, M.; Kuhlberg, J.; Bloom, J.D.; Edwards, M.; Haynes-Maslow, L. ‘There’s Not a Magic Wand’: How Rural Community Health Leaders Perceive Issues Related To Access to Healthy Foods And Physical Activity Across The Ecological Spectrum. J. Rural Community Dev. 2021, 16, 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Flora, C.B.; Flora, J.L.; Gasteyer, S.P. Rural Communities: Legacy and Change, 5th ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2016; ISBN 9780813349718. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich-Schad, J.D.; Duncan, C.M. People and Places Left behind: Work, Culture and Politics in the Rural United States. In Authoritarian Populism and the Rural World; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 59–79. ISBN 9781003162353. [Google Scholar]

- King, N. Template Analysis. In Qualitative Methods and Analysis in Organizational Research; Symon, G., Cassell, C., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- FIVIMS Framework for Food Security. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/fsn/docs/FIVIMS_Framework_of_Food_Security.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Simelane, K.S.; Worth, S. Food and Nutrition Security Theory. Food Nutr. Bull. 2020, 41, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planting Calendar for Burlington, VT. Available online: https://www.almanac.com/gardening/planting-calendar/zipcode/05401 (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Braveman, P.; Acker, J.; Arkin, E.; Badger, K.; Holm, N. Advancing Health Equity in Rural America; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- The Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis. Exploring Strategies to Improve Health and Equity in Rural Communities; The Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Afifi, R.A.; Parker, E.A.; Dino, G.; Hall, D.M.; Ulin, B. Reimagining Rural: Shifting Paradigms About Health and Well-Being in the Rural United States. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Research, and Medicine. The Social Environment in Rural America. In Rebuilding the Unity of Health and the Environment in Rural America; Merchant, J., Coussens, C., Gilbert, D., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-309-10047-2. [Google Scholar]

- Batey, L.; DeWitt, E.; Brewer, D.; Cardarelli, K.M.; Norman-Burgdolf, H. Exploring Food-Based Cultural Practices to Address Food Insecurity in Rural Appalachia. Health Educ. Behav. 2023, 50, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Carter, A. Social Determinants of Rural Food Security: Findings from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 107, 103256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, C.E.; Strong, A.M.; Mendez, V.E.; Lovell, S.T.; Troy, A.R.; Morris, W.B. Performing a New England Landscape: Viewing, Engaging, and Belonging. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 36, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, L.; Lockeretz, W.; Bell, R. Purchasing Foods Produced on Organic, Small and Local Farms: A Mixed Method Analysis of New England Consumers. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2009, 24, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles, M.T.; Alpaugh, M.; Bertmann, F.; Belarmino, E.; Bliss, S.; Laurent, J.; Malacarne, J.; McCarthy, A.; Merrill, S.; Schattman, R.E.; et al. Home Food Production and Food Security Since the COVID-19 Pandemic; College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Faculty Publications; The University of Vermont: Burlington, VT, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Niles, M.T.; McCarthy, A.C.; Malacarne, J.; Bliss, S.; Belarmino, E.H.; Laurent, J.; Merrill, S.C.; Nowak, S.A.; Schattman, R.E. Home and Wild Food Procurement Were Associated with Improved Food Security during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Two Rural US States. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Nutrition Service TEFAP Reach and Resiliency Grant Initiative. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/tefap/reach-resiliency-grant (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Ramadurai, V.; Sharf, B.F.; Sharkey, J.R. Rural Food Insecurity in the United States as an Overlooked Site of Struggle in Health Communication. Health Commun. 2012, 27, 794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, L.W.; Bitto, E.A.; Oakland, M.J.; Sand, M. Accessing Food Resources: Rural and Urban Patterns of Giving and Getting Food. Agric. Hum. Values 2007, 25, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, W.R.; Sharkey, J.R.; Nalty, C.C.; Xu, J. Government Capital, Intimate and Community Social Capital, and Food Security Status in Older Adults with Different Income Levels. Rural Sociol. 2014, 79, 505–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, U.; Morgan, E.H.; Graham, M.L.; Folta, S.C.; Seguin, R.A. Support and Sabotage: A Qualitative Study of Social Influences on Health Behaviors Among Rural Adults. J. Rural Health 2018, 34, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.A.; Mook, L.; Kao, C.-Y.; Murdock, A. Accountability and Relationship-Definition Among Food Banks Partnerships. Voluntas 2020, 31, 923–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calancie, L.; Stritzinger, N.; Konich, J.; Horton, C.; Allen, N.E.; Ng, S.W.; Weiner, B.J.; Ammerman, A.S. Food Policy Council Case Study Describing Cross-Sector Collaboration for Food System Change in a Rural Setting. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2017, 11, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataseven, C.; Nair, A.; Ferguson, M. An Examination of the Relationship between Intellectual Capital and Supply Chain Integration in Humanitarian Aid Organizations: A Survey-Based Investigation of Food Banks. Decis. Sci. 2018, 49, 827–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Governor’s Office of Policy Innovation and the Future Ending Hunger by 2030. Available online: https://www.maine.gov/future/hunger (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Horton, A. The Vermont Food Security Roadmap to 2035: Government Ensures Food Security for All in Vermont; Vermont General Assembly: Montpelier, VT, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.F. In Maine, a “Second Amendment for Food”? Available online: https://statecourtreport.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/maine-second-amendment-food (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Maine Food Sovereignty Act. In Title 7: Agriculture and Animals; Maine State Legislature: Augusta, ME, USA, 2021.

- ReFED U.S. Food Waste Policy Finder. Available online: https://policyfinder.refed.org (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- About the Network. Available online: https://vermontfarmtoschool.org/who-we-are/about-network (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Economic Research Service ERS County Typology Codes, 2015 ed.; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/county-typology-codes/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Chriest, A.; Niles, M. The Role of Community Social Capital for Food Security Following an Extreme Weather Event. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 64, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, M.K.; Massengale, S.H.; Cantrell, R. “No Money Exchanged Hands, No Bartering Took Place. But It’s Still Local Produce”: Understanding Local Food Systems in Rural Areas in the U.S. Heartland. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 78, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Employed Persons by Detailed Occupation, Sex, Race, and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm (accessed on 31 July 2024).

| Characteristic | Participants (n = 32) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Range | 24–66 |

| Median | 45 |

| Employer or profession (%) | |

| Public health/nutrition program | 34.38 |

| Food or farm non-profit organization | 28.13 |

| University Extension agent | 18.75 |

| Food hub | 9.38 |

| Clinical dietitian | 6.25 |

| Indigenous community leader | 3.13 |

| Gender (%) | |

| Female | 93.75 |

| Male | 6.25 |

| Race (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 91.63 |

| Black | 6.25 |

| Native American | 3.13 |

| State (n) | |

| Maine | 10 |

| New Hampshire | 7 |

| Vermont | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ryan, C.H.; Morgan, C.; Malacarne, J.G.; Belarmino, E.H. An Asset-Based Examination of Contextual Factors Influencing Nutrition Security: The Case of Rural Northern New England. Nutrients 2025, 17, 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020295

Ryan CH, Morgan C, Malacarne JG, Belarmino EH. An Asset-Based Examination of Contextual Factors Influencing Nutrition Security: The Case of Rural Northern New England. Nutrients. 2025; 17(2):295. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020295

Chicago/Turabian StyleRyan, Claire H., Caitlin Morgan, Jonathan G. Malacarne, and Emily H. Belarmino. 2025. "An Asset-Based Examination of Contextual Factors Influencing Nutrition Security: The Case of Rural Northern New England" Nutrients 17, no. 2: 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020295

APA StyleRyan, C. H., Morgan, C., Malacarne, J. G., & Belarmino, E. H. (2025). An Asset-Based Examination of Contextual Factors Influencing Nutrition Security: The Case of Rural Northern New England. Nutrients, 17(2), 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020295