Impact of Maternal Macronutrient Intake on Large for Gestational Age Neonates’ Risk Among Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Results from the Greek BORN2020 Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

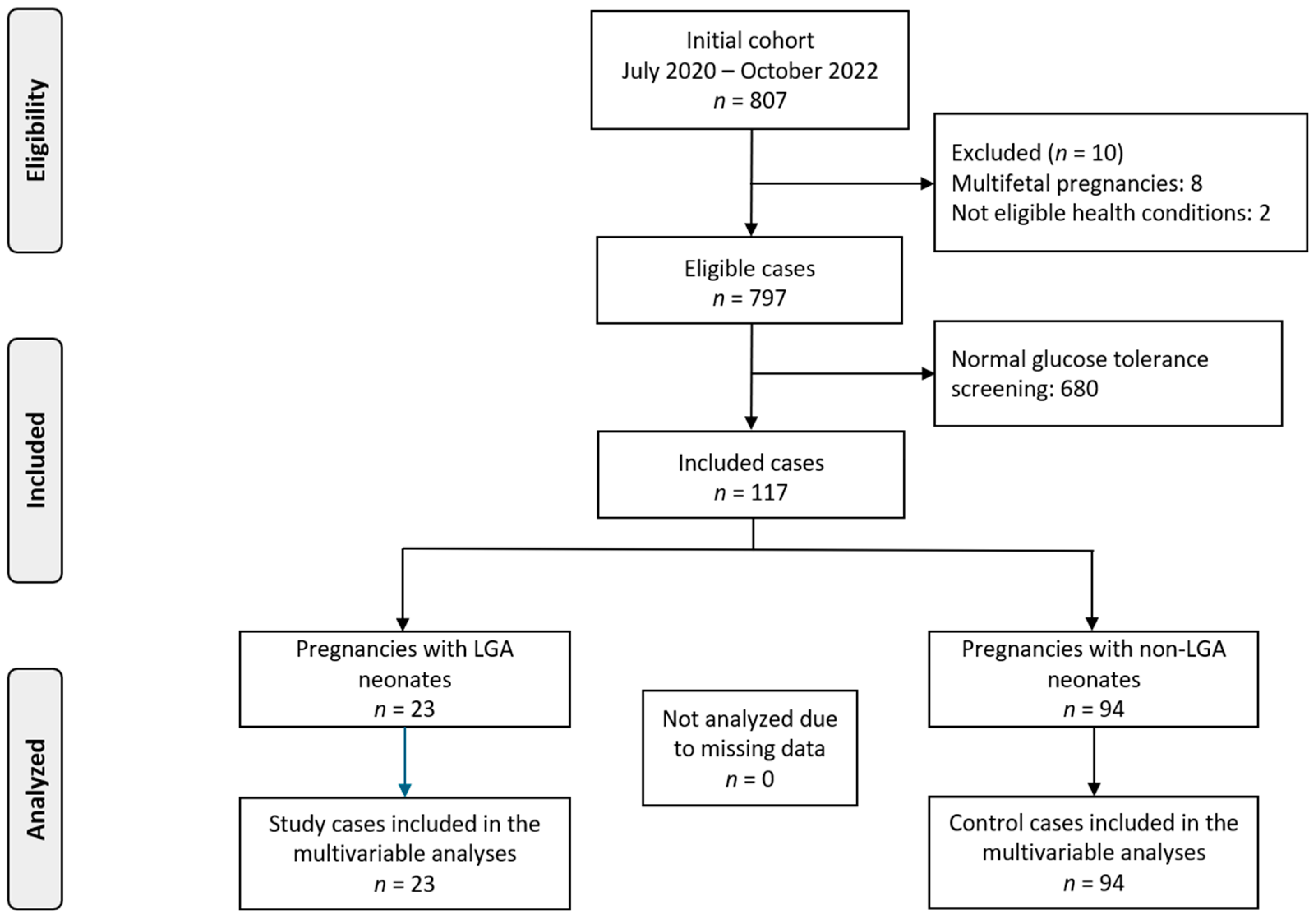

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Bioethics Committee

2.3. Dietary Assessment

2.4. Clinical and Anthropometric Data

2.5. Perinatal Outcome

2.6. Subgroup Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. LGA Risk in Normal-BMI Women

3.2. LGA Risk in High-BMI Women

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Interpretation of Our Findings

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Mo, M.; Muyiduli, X.; Wang, S.; Li, M.; Jiang, S.; Wu, Y.; Shao, B.; Shen, Y. The association of gestational diabetes mellitus with fetal birth weight. J. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2018, 32, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.H.; Lee, J.-E. Large for gestational age and obesity-related comorbidities. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2021, 30, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Dong, W.; Shangguan, F.; Li, H.; Yu, H.; Shen, J.; Su, Y.; Li, Z. Risk factors of large for gestational age among pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e092888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, K.; Grobman, W.; Wu, J.; Catalano, P.; Landon, M.; Scholtens, D.; Lowe, W.; Khan, S. Association of a Large-for-gestational Age Infant and Maternal Prediabetes and Diabetes 10-14 Years’ Postpartum in the HAPO Follow-up Study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, 756–758.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Zolezzi, I.; Samuel, T.M.; Spieldenner, J. Maternal nutrition: Opportunities in the prevention of gestational diabetes. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75 (Suppl. S1), 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, T.P.; Watkins, A.J.; Velazquez, M.A.; Mathers, J.C.; Prentice, A.M.; Stephenson, J.; Barker, M.; Saffery, R.; Yajnik, C.S.; Eckert, J.J. Origins of lifetime health around the time of conception: Causes and consequences. Lancet 2018, 391, 1842–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyrkou, C.; Athanasiadis, A.P.; Chourdakis, M.; Kada, S.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Menexes, G.; Michaelidou, A.-M. Are Maternal Dietary Patterns During Pregnancy Associated with the Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus? A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroeidi, I.; Manta, A.; Asimakopoulou, A.; Syrigos, A.; Paschou, S.A.; Vlachaki, E.; Nastos, C.; Kalantaridou, S.; Peppa, M. The role of the glycemic index and glycemic load in the dietary approach of gestational diabetes mellitus. Nutrients 2024, 16, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tranidou, A.; Dagklis, T.; Magriplis, E.; Apostolopoulou, A.; Tsakiridis, I.; Chroni, V.; Tsekitsidi, E.; Kalaitzopoulou, I.; Pazaras, N.; Chourdakis, M. Pre-Pregnancy Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Cohort Study in Greece. Nutrients 2023, 15, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanos, B.; Thanopoulou, A.; Anastasiou, E.; Assaad-Khalil, S.; Albache, N.; Bachaoui, M.; Slama, C.B.; El Ghomari, H.; Jotic, A.; Lalic, N. Relation of the Mediterranean diet with the incidence of gestational diabetes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumit, A.F.; Sarker, S. Evaluating the Effects of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus on Fetal Birth Weight. Dhaka Univ. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 29, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, A.; Magriplis, E.; Tsekitsidi, E.; Oikonomidou, A.C.; Papaefstathiou, E.; Tsakiridis, I.; Dagklis, T.; Chourdakis, M. Development and validation of a short culture-specific food frequency questionnaire for Greek pregnant women and their adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Nutrition 2021, 90, 111357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloks, S.A. The Regulation of Trans Fats in Food Products in the US and the EU. Utrecht Law Rev. 2019, 15, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coustan, D.R.; Lowe, L.P.; Metzger, B.E.; Dyer, A.R. The Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study: Paving the way for new diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 654.e1–654.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsagkari, A.; Pateras, K.; Ladopoulou, D.; Kornarou, E.; Vlachadis, N. Birthweight by gestational age reference centile charts for Greek neonates. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, C.B.; Jan, A. BMI Classification Percentile and Cut Off Points; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.-S.; Chen, Q.-Z.; He, J.-R.; Wei, X.-L.; Lu, J.-H.; Li, S.-H.; Wen, X.-X.; Chan, F.-F.; Chen, N.-N.; Qiu, L. Maternal dietary patterns and fetal growth: A large prospective cohort study in China. Nutrients 2016, 8, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnam, N. Improving maternal nutrition for better pregnancy outcomes. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2015, 74, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, C.M.; Rehbinder, E.M.; Carlsen, K.C.L.; Gudbrandsgard, M.; Carlsen, K.-H.; Haugen, G.; Hedlin, G.; Jonassen, C.M.; Sjøborg, K.D.; Landrø, L. Food and nutrient intake and adherence to dietary recommendations during pregnancy: A Nordic mother–child population-based cohort. Food Nutr. Res. 2019, 63, 3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, A.-R.; De Seymour, J.V.; Colega, M.; Chen, L.-W.; Chan, Y.-H.; Aris, I.M.; Tint, M.-T.; Quah, P.L.; Godfrey, K.M.; Yap, F. A vegetable, fruit, and white rice dietary pattern during pregnancy is associated with a lower risk of preterm birth and larger birth size in a multiethnic Asian cohort: The Growing Up in Singapore Towards healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Duan, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, Z.; Duan, J.; Cui, Z. Effects of prepregnancy dietary patterns on infant birth weight: A prospective cohort study. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023, 36, 2273216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, A.-R.; Chen, L.-W.; Lai, J.S.; Wong, C.H.; Neelakantan, N.; Van Dam, R.M.; Chong, M.F.-F. Maternal dietary patterns and birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Han, S.; Chen, G.-C.; Li, Z.-N.; Silva-Zolezzi, I.; Parés, G.V.; Wang, Y.; Qin, L.-Q. Effects of low-glycemic-index diets in pregnancy on maternal and newborn outcomes in pregnant women: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Ye, K.; Han, Y.; Sheng, J.; Jin, Z.; Bo, Q.; Hu, C.; Hu, C.; Li, L. Maternal and cord blood fatty acid patterns with excessive gestational weight gain and neonatal macrosomia. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 26, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gaccioli, F.; White, V.; Capobianco, E.; Powell, T.L.; Jawerbaum, A.; Jansson, T. Maternal overweight induced by a diet with high content of saturated fat activates placental mTOR and eIF2alpha signaling and increases fetal growth in rats. Biol. Reprod. 2013, 89, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Hortelano, J.A.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Garrido-Miguel, M.; Soriano-Cano, A.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Monitoring gestational weight gain and prepregnancy BMI using the 2009 IOM guidelines in the global population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Maternal Characteristics | LGA (n = 23) | Non-LGA (n = 94) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 33.17 ± 3.2 | 34.39 ± 4.72 | 0.24 |

| Maternal age > 35 years (%) | 7 (30.43%) | 44 (46.81%) | 0.24 |

| BMI pre-pregnancy overweight (%) | 6 (26.09%) | 15 (15.96%) | 0.83 |

| BMI pre-pregnancy obese (%) | 4 (17.39%) | 21 (22.34%) | 0.81 |

| Thyroid disease (%) | 4 (17.39%) | 9 (9.57%) | 0.48 |

| Parity | |||

| -0 (%) | 8 (34.78%) | 52 (55.32%) | 0.13 |

| -1 (%) | 12 (52.17%) | 32 (34.04%) | 0.17 |

| -2 (%) | 3 (13.04%) | 9 (9.57%) | 0.91 |

| Smoking (%) | 3 (13.04%) | 18 (19.15%) | 0.7 |

| Assisted reproductive technology (ART) (%) | 2 (8.7%) | 9 (9.57%) | 1 |

| Treated with diet | 18 (78.26%) | 74 (78.72%) | 1 |

| Treated with insulin | 5 (21.74%) | 20 (21.28%) | 1 |

| Period A | Period B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macronutrients | Reference Values | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) | Reference Values | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) |

| Energy (E) | Average energy requirements * | 0.21 | 0.99 (0.99, 1) | Average energy requirements * | 0.059 | 0.99 (0.99, 0.99) |

| Carbohydrates (absolute value) | - | 0.18 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) | - | 0.66 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) |

| Dietary Fiber | AI 25 g/day | 0.008 ** | 1.39 (1.11, 1.85) | AI 25 g/day | 0.057 | 1.27 (1.01, 1.68) |

| Total Carbohydrates % | 45–60 E% | 0.21 | 1.06 (0.96, 1.17) | 45–60 E% | 0.89 | 1 (0.91, 1.11) |

| Fats | - | 0.13 | 0.94 (0.88, 1) | - | 0.71 | 1.01 (0.94, 1.09) |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid, DHA | 250 mg/day DHA + EPA | 0.32 | 105.16 (0, 1.13 × 106) | 250 (+) 100–200 mg/day DHA + EPA | 0.12 | 586.73 (0.09, 2.47 × 106) |

| Saturated Fatty Acids (SFA) | AI ALAP | 0.23 | 0.89 (0.74, 1.06) | AI ALAP | 0.28 | 0.9 (0.74, 1.07) |

| Total Fat % | RI 20–35% | 0.13 | 0.91 (0.8, 1.01) | RI 20–35% | 0.66 | 0.97 (0.88, 1.07) |

| Protein | AR 0.66 g/kg bw per day | 0.45 | 1.02 (0.95, 1.11) | AR (+) 0.52 + 7.2 g/kg bw per day (1st and 2nd trimester) | 0.99 | 0.99 (0.92, 1.08) |

| Protein % | - | 0.37 | 1.12 (0.86, 1.48) | - | 0.73 | 1.04 (0.8, 1.33) |

| Vegetable Protein | - | 0.006 ** | 1.61 (1.2, 2.44) | - | 0.01 ** | 1.51 (1.14, 2.17) |

| Animal Protein | - | 0.63 | 0.98 (0.9, 1.06) | - | 0.3 | 0.95 (0.86, 1.03) |

| Mono-unsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFA) | - | 0.23 | 0.95 (0.86, 1.02) | - | 0.38 | 1.04 (0.94, 1.16) |

| Poly-unsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA) | - | 0.75 | 0.96 (0.71, 1.09) | - | 0.24 | 1.2 (0.87, 1.66) |

| Period A | Period B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macronutrients | Reference Values | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) | Reference Values | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) |

| Energy (E) | Average energy requirements * | 0.16 | 1 (0.99, 1) | Average energy requirements * | 0.055 | 1 (1, 1) |

| Carbohydrates (absolute value in gr) | - | 0.14 | 0.97 (0.93, 1) | - | 0.17 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) |

| Dietary Fiber | AI 25 g/day | 0.9 | 0.98 (0.79, 1.21) | AI 25 g/day | 0.28 | 1.12 (0.91, 1.42) |

| Total Carbohydrates % | 45–60 E% | 0.11 | 0.91 (0.8, 1.01) | 45–60 E% | 0.04 ** | 1.11 (1.01, 1.26) |

| Fats | - | 0.25 | 1.03 (0.97, 1.1) | - | 0.15 | 0.96 (0.9, 1.01) |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid, DHA | 250 mg/day DHA + EPA | 0.22 | 111.31 (0.07, 4.89 × 105) | 250 (+) 100–200 mg/day DHA + EPA | 0.65 | 0.07 (6.08 × 10−7, 3809.12) |

| Saturated Fatty Acids (SFA) | AI ALAP | 0.091 | 1.12 (0.98, 1.3) | AI ALAP | 0.014 ** | 0.71 (0.52, 0.9) |

| Total Fat % | RI 20–35% | 0.22 | 1.05 (0.97, 1.16) | RI 20–35% | 0.076 | 0.91 (0.8, 0.99) |

| Protein | AR 0.66 g/kg bw per day | 0.58 | 1.02 (0.95, 1.1) | AR (+) 0.52 + 7.2 g/kg bw per day (1st and 2nd trimester) | 0.99 | 1 (0.88, 1.13) |

| Protein % | - | 0.42 | 1.12 (0.85, 1.51) | - | 0.37 | 0.88 (0.65, 1.13) |

| Vegetable Protein | - | 0.15 | 1.21 (0.94, 1.65) | - | 0.018 ** | 1.61 (1.15, 2.68) |

| Animal Protein | - | 0.89 | 1 (0.93, 1.08) | - | 0.22 | 0.93 (0.82, 1.03) |

| Mono-unsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFA) | - | 0.54 | 1.02 (0.93, 1.11) | - | 0.33 | 0.96 (0.89, 1.03) |

| Poly-unsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA) | - | 0.81 | 0.97 (0.79, 1.15) | - | 0.89 | 1.02 (0.75, 1.36) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siargkas, A.; Tranidou, A.; Magriplis, E.; Tsakiridis, I.; Apostolopoulou, A.; Xenidis, T.; Pazaras, N.; Chourdakis, M.; Dagklis, T. Impact of Maternal Macronutrient Intake on Large for Gestational Age Neonates’ Risk Among Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Results from the Greek BORN2020 Cohort. Nutrients 2025, 17, 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020269

Siargkas A, Tranidou A, Magriplis E, Tsakiridis I, Apostolopoulou A, Xenidis T, Pazaras N, Chourdakis M, Dagklis T. Impact of Maternal Macronutrient Intake on Large for Gestational Age Neonates’ Risk Among Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Results from the Greek BORN2020 Cohort. Nutrients. 2025; 17(2):269. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020269

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiargkas, Antonios, Antigoni Tranidou, Emmanuela Magriplis, Ioannis Tsakiridis, Aikaterini Apostolopoulou, Theodoros Xenidis, Nikolaos Pazaras, Michail Chourdakis, and Themistoklis Dagklis. 2025. "Impact of Maternal Macronutrient Intake on Large for Gestational Age Neonates’ Risk Among Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Results from the Greek BORN2020 Cohort" Nutrients 17, no. 2: 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020269

APA StyleSiargkas, A., Tranidou, A., Magriplis, E., Tsakiridis, I., Apostolopoulou, A., Xenidis, T., Pazaras, N., Chourdakis, M., & Dagklis, T. (2025). Impact of Maternal Macronutrient Intake on Large for Gestational Age Neonates’ Risk Among Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Results from the Greek BORN2020 Cohort. Nutrients, 17(2), 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020269