Consumption of Energy Drinks and Attitudes Among School Students Following the Ban on Sales to Minors in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

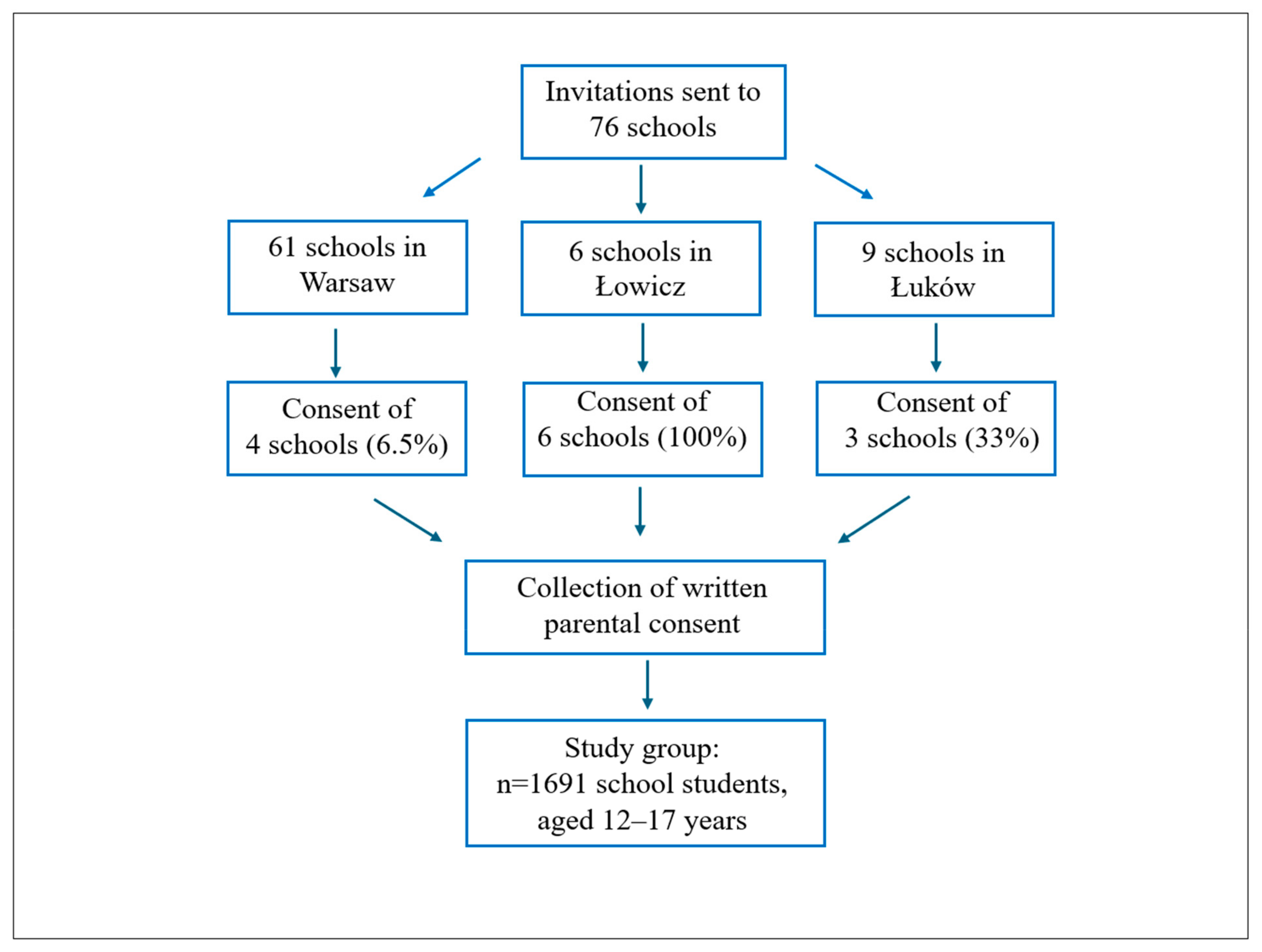

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Energy Drink Consumption Among Adolescents Following the Sales Ban

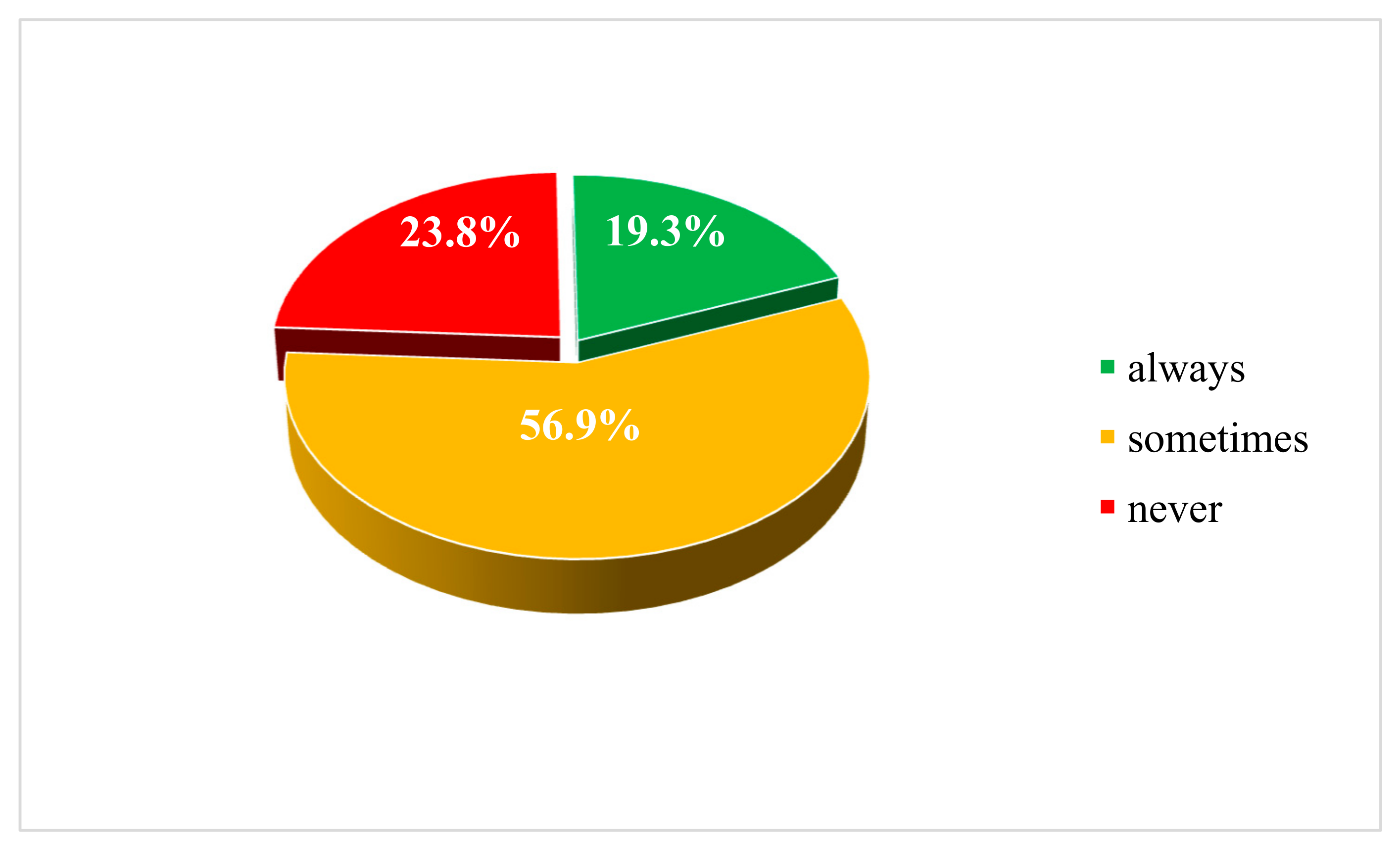

3.2. Attempts to Purchase Energy Drinks

3.3. Perception of the Harmfulness of Energy Drinks

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Napoje Energetyczne to Hit Pandemii. Rzeczpospolita. Available online: https://www.rp.pl/biznes/art38895561-napoje-energetyczne-to-hit-pandemii-zakaz-sprzedazy-dzieciom-nie-podoba (accessed on 17 March 2025). (In Polish).

- Energy Drink Sales in the United States from 2017 to 2024. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/558022/us-energy-drink-sales/ (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Wierzejska, R.; Jarosz, M. Energy drinks and health—Progress of the knowledge. Develop. Per. Med. 2011, 4, 507–513. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers, Amending Regulations (EC) No 1924/2006 and (EC) No 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and Repealing Commission Directive 87/250/EEC, Council Directive 90/496/EEC, Commission Directive 1999/10/EC, Directive 2000/13/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Directives 2002/67/EC and 2008/5/EC and Commission Regulation (EC) No 608/2004. OJ L 304, 22.11.2011:18–63. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32011R1169 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Nowak, D.; Jasionowski, A. Analysis of the Consumption of caffeinated energy drinks among Polish adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 7910–7921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadoni, C.; Peana, A.T. Energy drinks at adolescence: Awareness or unawareness? Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1080963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagim, A.R.; Harty, P.S.; Tinsley, G.M. i wsp.: International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: Energy drinks and energy shots. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2023, 20, 2171314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalese, M.; Denoth, F.; Siciliano, V.; Bastiani, L.; Cotichini, R.; Cutilli, A.; Molinaro, S. Energy drink and alcohol mixed energy drink use among high school adolescents: Association with risk taking behavior, social characteristics. Addict Behav. 2017, 72, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flotta, D.; Micò, R.; Nobile, C.G.; Pileggi, C.; Bianco, A.; Pavia, M. Consumption of energy drinks, alcohol, and alcohol-mixed energy drinks among Italian adolescents. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2014, 38, 1654–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.L. Caffeine use in children: What we know, what we have left to learn, and why we should worry. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009, 33, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reissig, C.J.; Strain, E.C.; Griffiths, R.R. Caffeinated energy drinks—A growing problem. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009, 99, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaar, L.; Vercammen, K.; Lu, C.; Richardson, S.; Tamez, M.; Mattei, J. Health effects and public health concerns of energy drink consumption in the United States: A Mini-Review. Front. Public Health 2017, 31, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, C.; Pritchard, M.; Bagnato, M.; Remedios, L.; Potvin, K.M. The extent of energy drink marketing on Canadian social media. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggers, D.; Asbridge, M.; Baskerville, N.B.; Reid, J.L.; Hammond, D. An experimental study on perceptions of energy drink ads among youth and young adults in Canada. Appetite 2020, 146, 104505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayalde, J.; Ta, D.; Adesanya, O.; Mandzufas, J.; Lombardi, K.; Trapp, G. Awake and alert: Examining the portrayal of energy drinks on TikTok. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, 633–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Maldonado, P.; Arias-Rico, J.; Romero-Palencia, A.; Román-Gutiérrez, A.D.; Ojeda-Ramírez, D.; Ramírez-Moreno, E. Consumption patterns of energy drinks in adolescents and their effects on behavior and mental health: A systematic review. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2022, 60, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Lavie, C.J.; Lippi, G. Strict regulations on energy drinks to protect Minors’ health in Europe—It is never too late to set things right at home. Prev. Med. 2024, 180, 107889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouja, C.; Kneale, D.; Brunton, G.; Raine, G.; Stansfield, C.; Sowden, A.; Sutcliffe, K.; Thomas, J. Consumption and effects of caffeinated energy drinks in young people: An overview of systematic reviews and secondary analysis of UK data to inform policy. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e047746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, J.; Antonio, B.; Arent, S.M.; Candow, D.G.; Escalante, G.; Evans, C.; Forbes, S.; Fukuda, D.; Gibbons, M.; Harty, P.; et al. Common questions and misconceptions about energy drinks: What does the scientific evidence really show? Nutrients 2024, 17, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, E. Poland bans energy drinks for under 18s. Lancet 2023, 401, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, M.; Babashahi, M.; Ramezani, S.; Dastgerdizad, H. A scoping review of policies related to reducing energy drink consumption in children. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act of 11 September 2015 on Public Health. Journal of Laws of 2024, Item 1670. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20240001670 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Act of 14 February 2020 Amending Certain Acts in Connection with the Promotion of Health-Promoting Consumer Choices. Journal of Laws of 2020, Item 1492. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20200001492 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Mularczyk-Tomczewska, P.; Lewandowska, A.; Kamińska, A.; Gałecka, M.; Atroszko, P.A.; Baran, T.; Koweszko, T.; Silczuk, A. Patterns of energy drink use, risk perception, and regulatory attitudes in the adult Polish population: Results of a cross-sectional survey. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musz, P.; Smorąg, W.; Ryś, G.; Gargasz, K.; Polak-Szczybyło, E. The frequency, preferences, and determinants of energy drink consumption among young Polish people after the introduction of the ban on sales to minors. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzielska, A.; Okulicz-Kozaryn, K. Używanie substancji psychoaktywnych i picie napojów energetyzujących przez młodzież w wieku 11-15 lat. Wyniki badań HBSC 2021/2022. Serwis Informacyjny Uzależnienia 2023, 4, 35–40. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Żyłka, K.; Ocieczek, A. Attitudes of Polish adolescents towards energy drinks. Part 2. Are these attitudes associated with energy drink consumption? Ann. Agri. Environ. Med. 2022, 29, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teijeiro, A.; Mourino, N.; García, G.; Candal-Pedreira, C.; Rey-Brandariz, J.; Guerra-Tort, C.; Mascareñas-García, M.; Montes-Martínez, A.; Varela-Lema, L.; Pérez-Ríos, M. Prevalence and characterization of energy drinks consumption in Europe: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2025, 3, e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granda, D.; Surała, O.; Malczewska-Lenczowska, J.; Szczepańska, B.; Pastuszak, A.; Sarnecki, R. Energy drink consumption among physically active Polish adolescents: Gender and age-specific public health issue. Int. J. Public Health 2024, 69, 1606906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucconi, S.V.; Volpato, C.; Adinolfi, F.; Gandini, E.; Gentile, E.; Loi, A.; Fioriti, L. Gathering consumption data on specific consumer groups of energy drinks. EFSA Support. Publ. 2013, 10, 394E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.E.; Dermen, K.H.; Lucke, J.F. Caffeinated energy drink use by U.S. adolescents aged 13–17: A national profile. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2018, 32, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aonso-Diego, G.; Krotter, A.; García-Pérez, Á. Prevalence of energy drink consumption world-wide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 2024, 119, 438–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błaszczyk-Bębenek, E.; Jagielski, P.; Schlegel-Zawadzka, M. Caffeine consumption in a group of adolescents from South East Poland—A cross sectional study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowska, K.; Winiarska-Mieczan, A.; Kwiecień, M.; Klebaniuk, R.; Danek-Majewska, A.; Kowalczuk-Vasilev, E.; Kwiatkowski, P. Consumption of energy drinks by teenagers in Lublin Province. Probl. Hig. Epidemiol. 2018, 99, 140–145. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Galimov, A.; Hanewinkel, R.; Hansen, J.; Unger, J.B.; Sussman, S.; Morgenstern, M. Energy drink consumption among German adolescents: Prevalence, correlates, and predictors of initiation. Appetite 2019, 139, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girán, J.; Girán, K.A.; Ormándlaky, D.; Pozsgai, É.; Kiss, I.; Kollányi, Z. Determinants of pupils’ energy drink consumption—Findings from a Hungarian primary school. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puupponen, M.; Tynjälä, J.; Tolvanen, A.; Välimaa, R.; Paakkari, L. Energy drink consumption among Finnish adolescents: Prevalence, associated background factors, individual resources, and family factors. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 620268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Miller, C.; Roberts, R.; Ettridge, K. Exploring the potential for graphic warning labels to reduce intentions to consume energy drinks. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2025, 36, e70004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Papiernik, M.; Mikulska, A.; Czarkowska-Paczek, B. Smoking, alcohol consumption, and illicit substances use among adolescents in Poland. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 2018, 13, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, S.; Wilkinson, C.; Thornton, L.; Feng, X.; Richmond, R. Online alcohol sales and home delivery: An international policy review and systematic literature review. Health Policy 2021, 125, 1222–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzejska, R.; Wolnicka, K.; Jarosz, M.; Jaczewska-Schuetz, J.; Taraszewska, A.; Siuba-Strzelińska, M. Caffeine intake from carbonated beverages among primary school-age children. Dev. Period. Med. 2016, 20, 150–156. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Frequent Consumption (n = 181) | Less Frequent Consumption (n = 1510) | Statistical Significance of Differences (p-Value) * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years): | p < 0.001 ** | ||

| range: | 13–17 | 12–17 | |

| quartiles Q1/Q2/Q3 | 16/16/17 | 14/16/17 | |

| mean age | 16.1 | 15.5 | |

| standard deviation | 1.1 | 1.4 | |

| School type: | p < 0.001 | ||

| primary | 8.3% | 25.4% | |

| secondary | 91.7% | 74.6% | |

| Gender: | NS | ||

| boys | 59.1% | 58.5% | |

| girls | 40.3% | 41.4% | |

| non-binary | 0.6% | 0.1% | |

| Place of residence: | p < 0.001 | ||

| urban | 31.5% | 57.4% | |

| rural | 68.5%, | 42.6%, | |

| Awareness of the ban: | p < 0.001 | ||

| yes | 88.4% | 98.4% | |

| no | 11.6% | 1.6% | |

| Perception that the ban makes obtaining drinks difficult: | NS | ||

| yes | 37.6% | 42.4% | |

| no | 62.4% | 57.6% | |

| Belief in harmful effects: | p < 0.001 | ||

| yes | 14.9% | 46.4% | |

| no | 85.1% | 53.6% |

| Variables | Refusal Always n (%) | Refusal Sometimes n (%) | Refusal Never n (%) | Total n (%) | Statistical Significance of Differences (p-Value) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary school | 10 (14.3) | 43 (61.4) | 17 (24.3) | 70 (100) | p = 0.033 |

| Secondary school | 70 (13.8) | 236 (46.4) | 203 (39.9) | 509 (100) | |

| Boys | 60 (16.2) | 182 (49.1) | 129 (34.8) | 371 (100) | p = 0.028 |

| Girls | 20 (9.6) | 97 (46.6) | 91 (43.8) | 208 (100) | |

| Students living in urban areas | 37 (14.7) | 133 (52.8) | 82 (32.5) | 252 (100) | NS |

| Students living in rural areas | 43 (13.1) | 146 (44.6) | 138 (42.2) | 327 (100) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wierzejska, R.E.; Taraszewska, A.M.; Wiosetek-Reske, A.; Poznańska, A. Consumption of Energy Drinks and Attitudes Among School Students Following the Ban on Sales to Minors in Poland. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3167. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193167

Wierzejska RE, Taraszewska AM, Wiosetek-Reske A, Poznańska A. Consumption of Energy Drinks and Attitudes Among School Students Following the Ban on Sales to Minors in Poland. Nutrients. 2025; 17(19):3167. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193167

Chicago/Turabian StyleWierzejska, Regina Ewa, Anna Małgorzata Taraszewska, Agnieszka Wiosetek-Reske, and Anna Poznańska. 2025. "Consumption of Energy Drinks and Attitudes Among School Students Following the Ban on Sales to Minors in Poland" Nutrients 17, no. 19: 3167. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193167

APA StyleWierzejska, R. E., Taraszewska, A. M., Wiosetek-Reske, A., & Poznańska, A. (2025). Consumption of Energy Drinks and Attitudes Among School Students Following the Ban on Sales to Minors in Poland. Nutrients, 17(19), 3167. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193167