Effects of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Supplementation and Aerobic Exercise on Metabolic Health and Physical Performance in Aged Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. NMN Administration

2.3. Exercise Intervention Protocol

2.4. Body Composition

2.5. Endurance Exercise Performance Test

2.6. Forelimb Grip Strength

2.7. Weights Test

2.8. Kondziela’s Inverted Screen Test

2.9. Functional Strength Test

2.10. Rotarod Balance Performance Test

2.11. Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT)

2.12. Measurement of Metabolic Rate

2.13. Tissue and Sample Collection

2.14. Measurement of Biochemical Parameters

2.15. Western Blotting

2.16. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

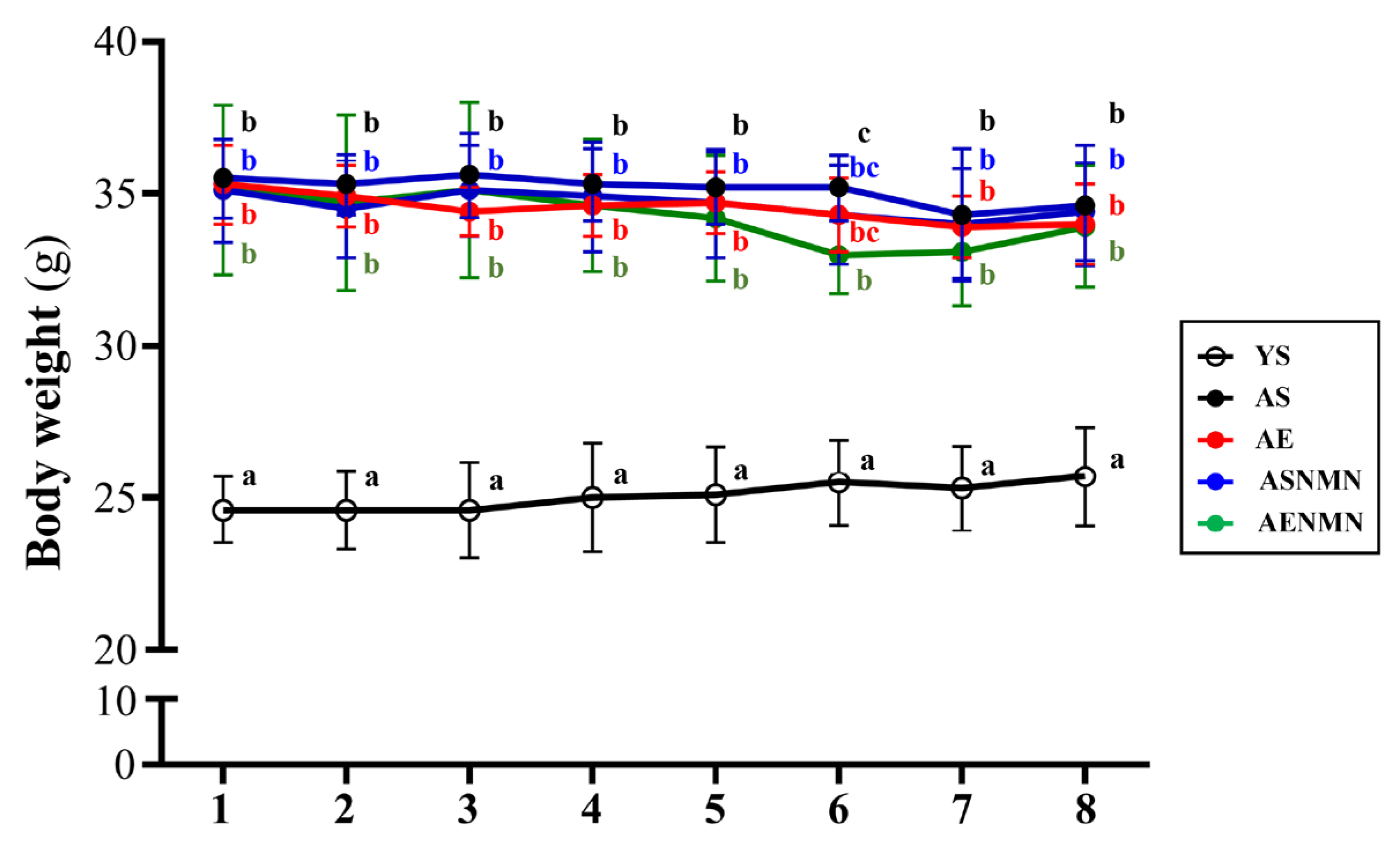

3.1. General Characteristics of Aging Mice with NMN Supplementation and Exercise Training

3.2. Effect of NMN Supplementation and Exercise Training on the Body Composition of Aging Mice

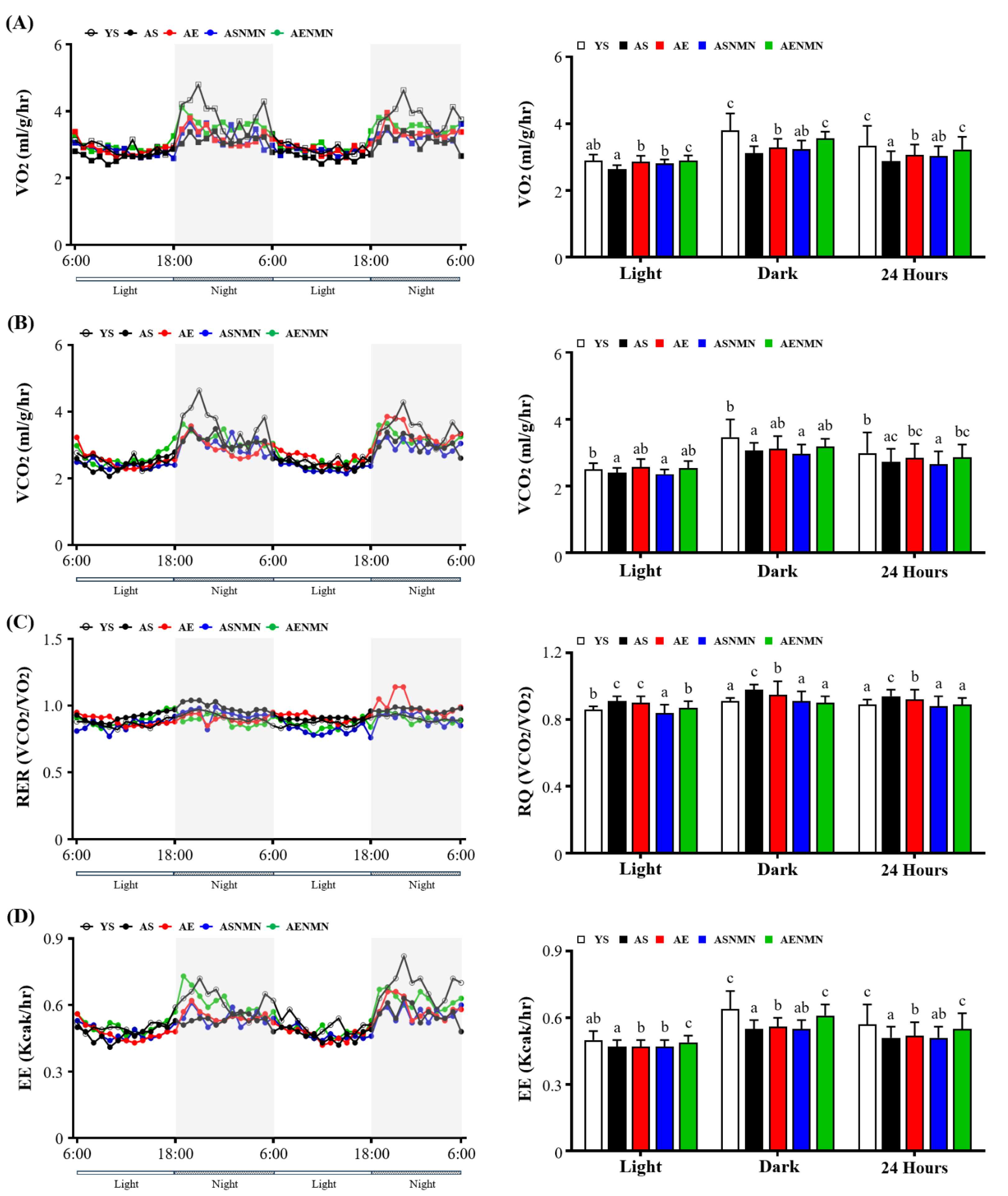

3.3. Effect of NMN Supplementation and Exercise Training on Energy Metabolism and Physical Activity

3.4. Effect of NMN Supplementation and Exercise Training on Oral Glucose Tolerance Test Results

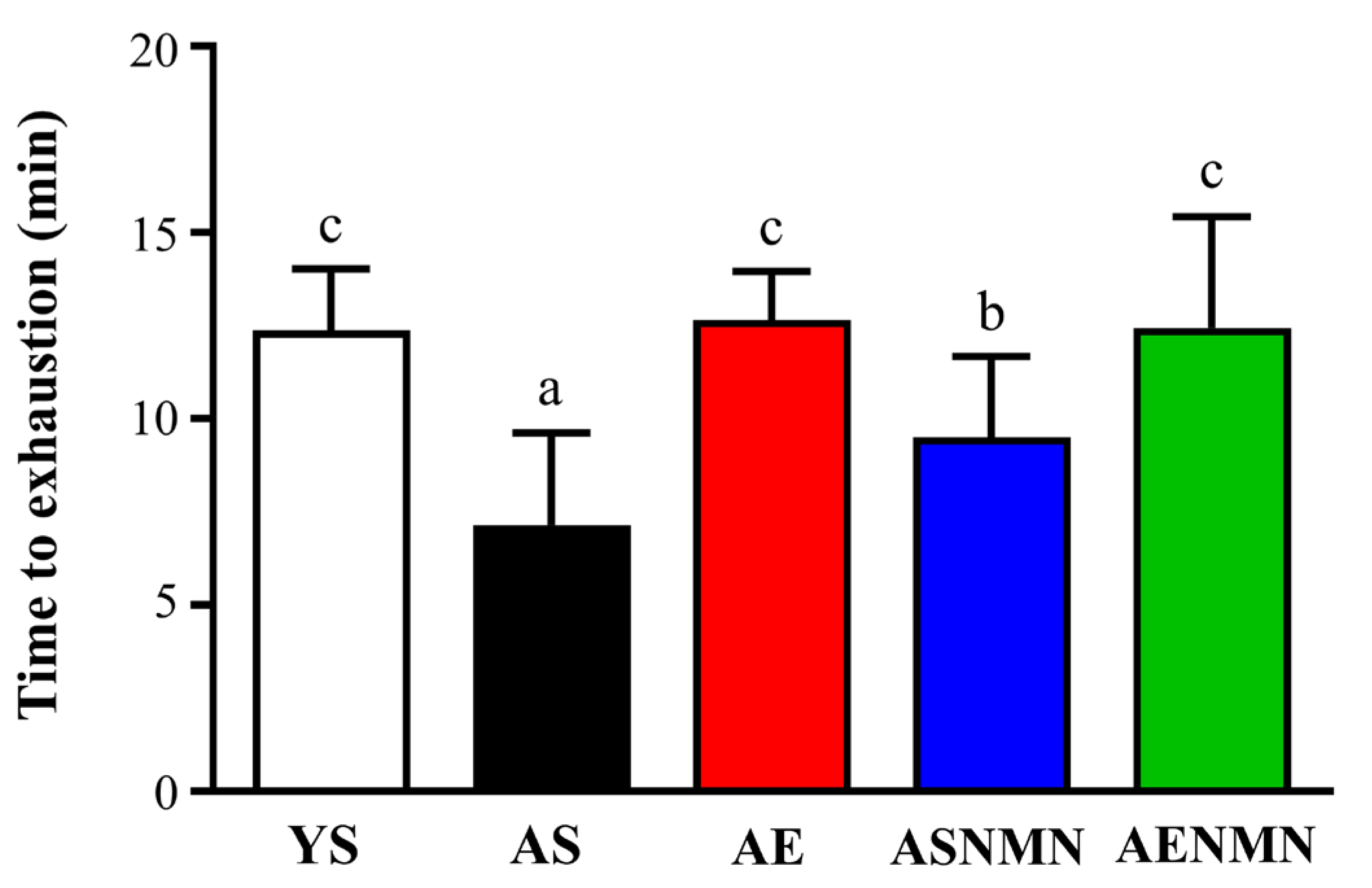

3.5. Effects of NMN Supplementation and Exercise Training on Endurance Performance in Aging Mice

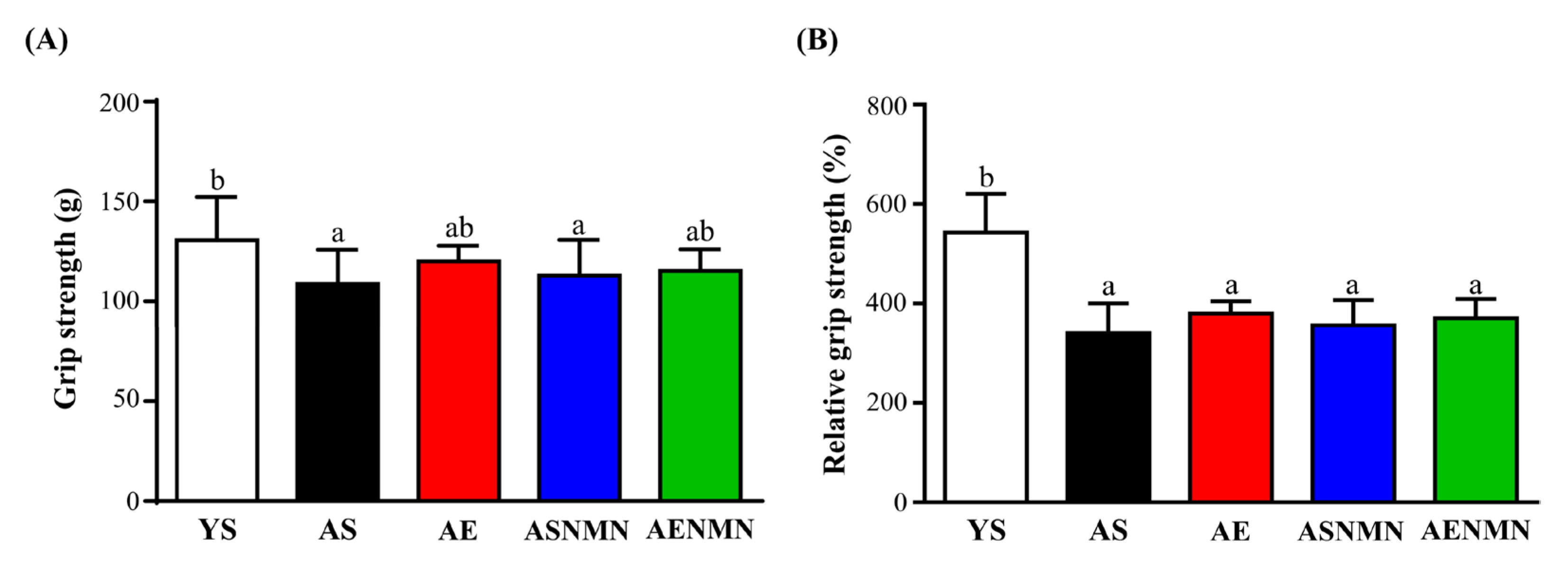

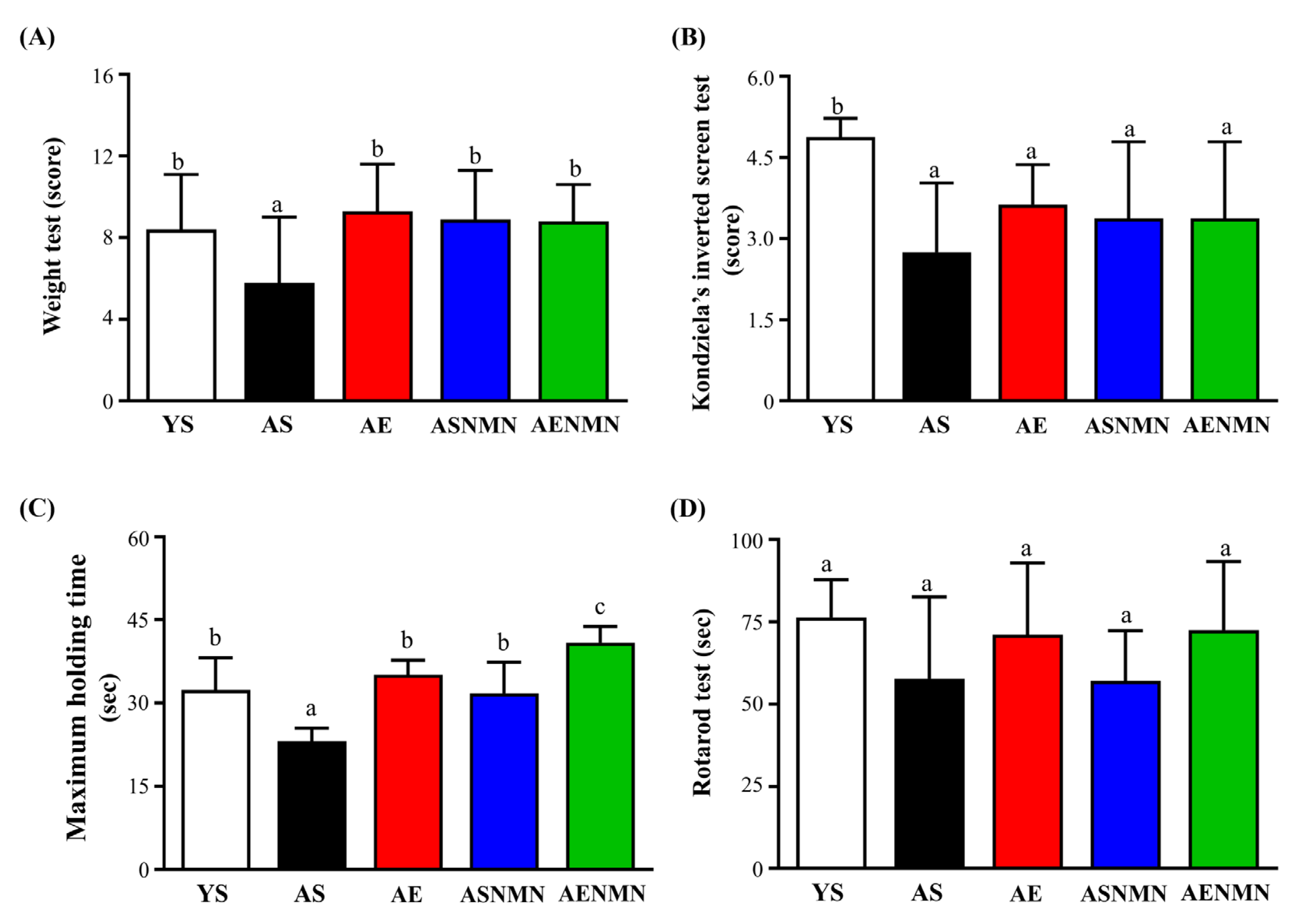

3.6. Effects of NMN Supplementation and Exercise Training on Muscle Strength and Physical Function in Aging Mice

3.7. Effect of NMN Supplementation and Exercise Training on Biochemical Variables at the End of the Experiment

3.8. Effect of NMN Supplementation and Exercise Training on Western Blot Analysis of Gastrocnemius Muscle

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, J.; Huang, X.; Dou, L.; Yan, M.; Shen, T.; Tang, W.; Li, J. Aging and aging-related diseases: From molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chubanava, S.; Treebak, J.T. Regular exercise effectively protects against the aging-associated decline in skeletal muscle NAD content. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 173, 112109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkwood, T.B. Understanding the odd science of aging. Cell 2005, 120, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, L.; Degens, H.; Li, M.; Salviati, L.; Lee, Y.I.; Thompson, W.; Kirkland, J.L.; Sandri, M. Sarcopenia: Aging-Related Loss of Muscle Mass and Function. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 427–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, I. Sustained caloric restriction in health. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fang, J.; Yue, H.; Ma, S.; Guan, F. Aging and age-related diseases: From mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Biogerontology 2021, 22, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, M.; Niermann, C.; Jekauc, D.; Woll, A. Long-term health benefits of physical activity—A systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J.M.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q.A. Antiaging Strategies and Remedies: A Landscape of Research Progress and Promise. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 408–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzik, D.; Jonas, W.; Joisten, N.; Belen, S.; Wüst, R.C.I.; Guillemin, G.; Zimmer, P. Tissue-specific effects of exercise as NAD(+) -boosting strategy: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Acta Physiol. 2023, 237, e13921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, N.; Dölle, C.; Ziegler, M. The power to reduce: Pyridine nucleotides-small molecules with a multitude of functions. Biochem. J. 2007, 402, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajman, L.; Chwalek, K.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic Potential of NAD-Boosting Molecules: The In Vivo Evidence. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogan, K.L.; Brenner, C. Nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and nicotinamide riboside: A molecular evaluation of NAD+ precursor vitamins in human nutrition. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2008, 28, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Mo, F.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, M.; Wei, X. Nicotinamide Mononucleotide: A Promising Molecule for Therapy of Diverse Diseases by Targeting NAD+ Metabolism. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, J.; Baur, J.A.; Imai, S.I. NAD(+) Intermediates: The Biology and Therapeutic Potential of NMN and NR. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poljsak, B.; Kovač, V.; Milisav, I. Healthy Lifestyle Recommendations: Do the Beneficial Effects Originate from NAD(+) Amount at the Cellular Level? Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 8819627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaku, K.; Palikhe, S.; Iqbal, T.; Hayat, F.; Watanabe, Y.; Fujisaka, S.; Izumi, H.; Yoshida, T.; Karim, M.; Uchida, H.; et al. Nicotinamide riboside and nicotinamide mononucleotide facilitate NAD(+) synthesis via enterohepatic circulation. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Dai, J.; Ai, H.; Du, W.; Ji, H. β-Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Promotes Cell Proliferation and Hair Growth by Reducing Oxidative Stress. Molecules 2024, 29, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Chabloz, S.; Lapides, R.A.; Roider, E.; Ewald, C.Y. Potential Synergistic Supplementation of NAD+ Promoting Compounds as a Strategy for Increasing Healthspan. Nutrients 2023, 15, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinescu, G.C.; Popescu, R.G.; Stoian, G.; Dinischiotu, A. β-nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) production in Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.; Xie, Y.; Peng, H.; Li, T.; Zou, X.; Yue, F.; Guo, J.; Rong, L. Advancements in NMN biotherapy and research updates in the field of digestive system diseases. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, T.; Giles, C.B.; Tarantini, S.; Yabluchanskiy, A.; Balasubramanian, P.; Gautam, T.; Csipo, T.; Nyúl-Tóth, Á.; Lipecz, A.; Szabo, C.; et al. Nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) supplementation promotes anti-aging miRNA expression profile in the aorta of aged mice, predicting epigenetic rejuvenation and anti-atherogenic effects. Geroscience 2019, 41, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H. A Multicentre, Randomised, Double Blind, Parallel Design, Placebo Controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Uthever (NMN Supplement), an Orally Administered Supplementation in Middle Aged and Older Adults. Front. Aging 2022, 3, 851698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, L.; Maier, A.B.; Tao, R.; Lin, Z.; Vaidya, A.; Pendse, S.; Thasma, S.; Andhalkar, N.; Avhad, G.; Kumbhar, V. The efficacy and safety of β-nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) supplementation in healthy middle-aged adults: A randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-dependent clinical trial. Geroscience 2023, 45, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igarashi, M.; Nakagawa-Nagahama, Y.; Miura, M.; Kashiwabara, K.; Yaku, K.; Sawada, M.; Sekine, R.; Fukamizu, Y.; Sato, T.; Sakurai, T.; et al. Chronic nicotinamide mononucleotide supplementation elevates blood nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide levels and alters muscle function in healthy older men. NPJ Aging 2022, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.F.; Yoshida, S.; Stein, L.R.; Grozio, A.; Kubota, S.; Sasaki, Y.; Redpath, P.; Migaud, M.E.; Apte, R.S.; Uchida, K.; et al. Long-Term Administration of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Mitigates Age-Associated Physiological Decline in Mice. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrick-Ranson, G.; Howden, E.J.; Brazile, T.L.; Levine, B.D.; Reading, S.A. Effects of aging and endurance exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiac structure and function in healthy midlife and older women. J. Appl. Physiol. 2023, 135, 1215–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, S.; Nisar, S.; Bhat, A.A.; Shah, A.R.; Frenneaux, M.P.; Fakhro, K.; Haris, M.; Reddy, R.; Patay, Z.; Baur, J.; et al. Role of NAD(+) in regulating cellular and metabolic signaling pathways. Mol. Metab. 2021, 49, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, T.G.; Maroto, R.; Fry, C.S.; Brightwell, C.R.; Rasmussen, B.B. Measuring Exercise Capacity and Physical Function in Adult and Older Mice. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2021, 76, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBrasseur, N.K.; Schelhorn, T.M.; Bernardo, B.L.; Cosgrove, P.G.; Loria, P.M.; Brown, T.A. Myostatin inhibition enhances the effects of exercise on performance and metabolic outcomes in aged mice. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2009, 64, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Chen, M.J.; Huang, H.W.; Wu, W.K.; Lee, Y.W.; Kuo, H.C.; Huang, C.C. Probiotic Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Tana Isolated from an International Weightlifter Enhances Exercise Performance and Promotes Antifatigue Effects in Mice. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deacon, R.M. Measuring the strength of mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 76, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, K.; Gessner, D.K.; Seimetz, M.; Banisch, J.; Ringseis, R.; Eder, K.; Weissmann, N.; Mooren, F.C. Functional and muscular adaptations in an experimental model for isometric strength training in mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graber, T.G.; Ferguson-Stegall, L.; Liu, H.; Thompson, L.V. Voluntary Aerobic Exercise Reverses Frailty in Old Mice. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2015, 70, 1045–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Soh, K.G.; Omar Dev, R.D.; Talib, O.; Xiao, W.; Soh, K.L.; Ong, S.L.; Zhao, C.; Galeru, O.; Casaru, C. Aerobic Exercise Combination Intervention to Improve Physical Performance Among the Elderly: A Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 798068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.U.; Qadeer, A.; Wu, Z. Role and Potential Mechanisms of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide in Aging. Aging Dis. 2024, 15, 565–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Qiu, F.; Li, Y.; Che, T.; Li, N.; Zhang, S. Mechanisms of the NAD(+) salvage pathway in enhancing skeletal muscle function. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1464815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.Z.; No, M.H.; Heo, J.W.; Park, D.H.; Kang, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kwak, H.B. Role of exercise in age-related sarcopenia. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2018, 14, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, B.B.; Hamer, H.M.; Snijders, T.; van Kranenburg, J.; Frijns, D.; Vink, H.; van Loon, L.J. Skeletal muscle capillary density and microvascular function are compromised with aging and type 2 diabetes. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 116, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Ma, J.; Fang, Q.; Peng, Q.; Jiao, X.; Hu, W.; Zhao, Q.; Kong, Y.; Liu, F.; Shi, X.; et al. Structural insights into Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris NAD(+) biosynthesis via the NAM salvage pathway. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, A.E.; Sinclair, D.A. Sirtuins and NAD(+) in the Development and Treatment of Metabolic and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 868–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Huang, G.X.; Bonkowski, M.S.; Longchamp, A.; Li, C.; Schultz, M.B.; Kim, L.J.; Osborne, B.; Joshi, S.; Lu, Y.; et al. Impairment of an Endothelial NAD(+)-H(2)S Signaling Network Is a Reversible Cause of Vascular Aging. Cell 2018, 173, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.J.; Zhang, T.N.; Chen, H.H.; Yu, X.F.; Lv, J.L.; Liu, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.S.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, J.Q.; Wei, Y.F.; et al. The sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Q.; Zhou, X.; Xu, K.; Liu, S.; Zhu, X.; Yang, J. The Safety and Antiaging Effects of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide in Human Clinical Trials: An Update. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 1416–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, L.L.; Yeo, D. Maintenance of NAD+ Homeostasis in Skeletal Muscle during Aging and Exercise. Cells 2022, 11, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Báez, A.; Castro Romero, I.; Chihu Amparan, L.; Castañeda, J.R.; Ayala, G. The Insulin Receptor Substrate 2 Mediates the Action of Insulin on HeLa Cell Migration via the PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 2296–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, K.; Ogawa, Y. Forkhead box class O family member proteins: The biology and pathophysiological roles in diabetes. J. Diabetes Investig. 2017, 8, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xu, M.; Geng, M.; Chen, S.; Little, P.J.; Xu, S.; Weng, J. Targeting protein modifications in metabolic diseases: Molecular mechanisms and targeted therapies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A. Crosstalk between Oxidative Stress and SIRT1: Impact on the Aging Process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 3834–3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, P.S.; Boriek, A.M. SIRT1 Regulation in Ageing and Obesity. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2020, 188, 111249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imi, Y.; Amano, R.; Kasahara, N.; Obana, Y.; Hosooka, T. Nicotinamide mononucleotide induces lipolysis by regulating ATGL expression via the SIRT1-AMPK axis in adipocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2023, 34, 101476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.L. Sirt1 and the Mitochondria. Mol. Cells 2016, 39, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.B.; Bao, J.; Deng, C.X. Emerging roles of SIRT1 in fatty liver diseases. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 13, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | YS | AS | AE | ASNMN | AENMN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final BW (g) | 24.03 ± 1.77 a | 32.16 ± 1.98 b | 31.63 ± 1.06 b | 31.71 ± 1.72 b | 31.21 ± 1.68 b |

| Water intake (mL/mouse/day) | 4.51 ± 0.92 a | 8.26 ± 1.32 d | 7.17 ± 0.83 b | 7.69 ± 1.16 c | 7.33 ± 1.02 bc |

| Food intake (g/mouse/day) | 4.16 ± 0.62 a | 5.68 ± 0.79 d | 5.78 ± 0.81 d | 4.85 ± 0.89 b | 5.32 ± 0.82 c |

| Calories intake (kcal/mouse/day) | 16.44 ± 2.46 a | 22.43 ± 3.1 c | 22.85 ± 3.19 c | 19.16 ± 3.53 b | 18.62 ± 2.89 b |

| Absolute weight | |||||

| Liver (g) | 1.04 ± 0.14 a | 1.61 ± 0.16 b | 1.52 ± 0.17 b | 1.48 ± 0.15 b | 1.68 ± 0.39 b |

| Kidney (g) | 0.31 ± 0.02 a | 0.46 ± 0.03 b | 0.48 ± 0.02 b | 0.46 ± 0.04 b | 0.46 ± 0.03 b |

| Muscle (g) | 0.29 ± 0.02 a | 0.30 ± 0.02 a | 0.30 ± 0.02 a | 0.30 ± 0.02 a | 0.30 ± 0.02 a |

| EFP (g) | 0.36 ± 0.06 a | 0.64 ± 0.16 c | 0.51 ± 0.12 b | 0.64 ± 0.06 c | 0.49 ± 0.14 b |

| Heart (g) | 0.13 ± 0.03 a | 0.19 ± 0.02 b | 0.19 ± 0.02 b | 0.21 ± 0.04 b | 0.20 ± 0.01 b |

| Lung (g) | 0.18 ± 0.04 a | 0.20 ± 0.03 b | 0.20 ± 0.02 b | 0.21 ± 0.04 b | 0.20 ± 0.05 b |

| Brain (g) | 0.46 ± 0.02 a | 0.49 ± 0.01 b | 0.49 ± 0.02 b | 0.48 ± 0.03 b | 0.49 ± 0.02 b |

| BAT (g) | 0.06 ± 0.01 ab | 0.05 ± 0.01 ab | 0.05 ± 0.01 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 ab | 0.06 ± 0.02 b |

| Relative weight | |||||

| Liver (%) | 3.96 ± 0.53 a | 6.13 ± 0.59 b | 5.79 ± 0.66 b | 5.65 ± 0.58 b | 6.39 ± 1.48 b |

| Kidney (%) | 1.19 ± 0.30 a | 1.77 ± 0.10 b | 1.84 ± 0.09 b | 1.77 ± 0.14 b | 1.77 ± 0.13 b |

| Muscle (%) | 1.09 ± 0.09 a | 1.15 ± 0.10 a | 1.15 ± 0.07 a | 1.15 ± 0.09 a | 1.15 ± 0.09 a |

| EFP (%) | 1.39 ± 0.23 a | 2.46 ± 0.62 c | 1.94 ± 0.47 b | 2.44 ± 0.22 c | 1.88 ± 0.53 b |

| Heart (%) | 0.51 ± 0.13 a | 0.72 ± 0.10 b | 0.73 ± 0.07 b | 0.79 ± 0.16 b | 0.77 ± 0.06 b |

| Lung (%) | 0.68 ± 0.14 a | 0.77 ± 0.10 a | 0.78 ± 0.09 a | 0.78 ± 0.14 a | 0.77 ± 0.19 a |

| Brain (%) | 1.74 ± 0.07 a | 1.88 ± 0.05 b | 1.88 ± 0.06 b | 1.84 ± 0.10 b | 1.88 ± 0.08 b |

| BAT (%) | 0.21 ± 0.03 a | 0.20 ± 0.04 a | 0.17 ± 0.03 a | 0.19 ± 0.04 a | 0.22 ± 0.07 a |

| Characteristic | YS | AS | AE | ASNMN | AENMN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 26.50 ± 1.33 a | 34.83 ± 2.37 b | 34.98 ± 1.29 b | 34.26 ± 2.25 b | 34.69 ± 2.03 b |

| Fat mass (g) | 3.19 ± 0.35 a | 4.50 ± 0.48 b | 4.24 ± 0.64 b | 4.30 ± 0.46 b | 4.45 ± 1.14 b |

| Lean mass (g) | 18.97 ± 1.09 a | 25.01 ± 1.65 b | 25.37 ± 0.77 b | 25.05 ± 1.84 b | 25.45 ± 1.48 b |

| Free body fluid (g) | 2.04 ± 0.15 a | 2.74 ± 0.20 b | 3.01 ± 0.59 b | 2.73 ± 0.19 b | 3.01 ± 0.24 b |

| OGTT | YS | AS | AE | ASNMN | AENMN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min (mg/dL) | 130.88 ± 7.18 a | 133.13 ± 9.58 a | 130.88 ± 4.71 a | 128.75 ± 7.01 a | 131.25 ± 5.92 a |

| 15 min (mg/dL) | 258.63 ± 42.70 a | 328.63 ± 42.70 b | 315.13 ± 71.21 ab | 309.38 ± 85.94 ab | 289.75 ± 48.13 ab |

| 30 min (mg/dL) | 242.25 ± 36.56 bc | 267.75 ± 53.13 c | 229.13 ± 35.68 abc | 218.75 ± 52.90 ab | 197.25 ± 23.43 a |

| 60 min (mg/dL) | 205.38 ± 26.75 b | 199.25 ± 26.95 b | 202.00 ± 19.41 b | 183.50 ± 45.96 ab | 159.38 ± 28.80 a |

| 120 min (mg/dL) | 160.50 ± 13.23 bc | 167.63 ± 18.52 c | 159.63 ± 22.98 bc | 146.63 ± 18.16 ab | 137.25 ± 25.84 a |

| AUC | 25,538.44 ± 3093.39 ab | 25,544.06 ± 3791.65 b | 24,779.06 ± 3156.31 b | 23,123.44 ± 4195.80 ab | 21,075.00 ± 2685.25 a |

| Parameters | YS | AS | AE | ASNMN | AENMN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST (U/L) | 166.63 ± 21.0 a | 126.38 ± 60.35 a | 142.00 ± 54.82 a | 169.00 ± 67.07 a | 157.13 ± 97.44 a |

| ALT (U/L) | 35.50 ± 4.34 a | 39.63 ± 6 a | 39.38 ± 8 a | 41.13 ± 18 a | 46.75 ± 19 a |

| CPK (U/L) | 370.00 ± 74.73 a | 312.25 ± 174.18 a | 362.63 ± 200.42 a | 394.88 ± 205.50 a | 370.00 ± 362.49 a |

| TP (g/dL) | 5.96 ± 0.15 a | 5.73 ± 0.19 a | 5.81 ± 0.43 a | 5.78 ± 0.12 a | 5.80 ± 0.48 a |

| ALB (g/dL) | 3.70 ± 0.38 a | 3.63 ± 0.19 a | 3.70 ± 0.38 a | 3.65 ± 0.10 a | 3.64 ± 0.29 a |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 24.56 ± 1.75 a | 32.11 ± 4.82 b | 30.66 ± 3.66 b | 31.86 ± 4.30 b | 31.91 ± 7.80 b |

| TC (mg/dL) | 62.29 ± 2.93 a | 58.38 ± 7.42 a | 59.88 ± 8.34 a | 61.29 ± 4.90 a | 61.13 ± 10.86 a |

| TG (mg/dL) | 95.29 ± 13.39 b | 90.25 ± 14.68 b | 70.00 ± 9.13 a | 68.29 ± 6.82 a | 71.25 ± 11.91 a |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 70.38 ± 2.36 a | 68.28 ± 5.02 a | 73.18 ± 3.77 a | 72.89 ± 4.04 a | 75.23 ± 2.95 a |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 8.80 ± 0.95 a | 10.01 ± 1.61 a | 9.73 ± 1.63 a | 11.63 ± 0.63 a | 11.25 ± 3.22 a |

| NAMPT(µg/mL) | 7.49 ± 1.96 c | 3.49 ± 0.44 a | 5.63 ± 0.36 b | 5.68 ± 0.92 b | 6.07 ± 0.55 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hsu, Y.-J.; Lee, M.-C.; Fan, H.-Y.; Lo, Y.-C. Effects of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Supplementation and Aerobic Exercise on Metabolic Health and Physical Performance in Aged Mice. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3148. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193148

Hsu Y-J, Lee M-C, Fan H-Y, Lo Y-C. Effects of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Supplementation and Aerobic Exercise on Metabolic Health and Physical Performance in Aged Mice. Nutrients. 2025; 17(19):3148. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193148

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsu, Yi-Ju, Mon-Chien Lee, Huai-Yu Fan, and Yu-Ching Lo. 2025. "Effects of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Supplementation and Aerobic Exercise on Metabolic Health and Physical Performance in Aged Mice" Nutrients 17, no. 19: 3148. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193148

APA StyleHsu, Y.-J., Lee, M.-C., Fan, H.-Y., & Lo, Y.-C. (2025). Effects of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Supplementation and Aerobic Exercise on Metabolic Health and Physical Performance in Aged Mice. Nutrients, 17(19), 3148. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193148