Perceptions Regarding Healthy Eating Based on Concept Mapping

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

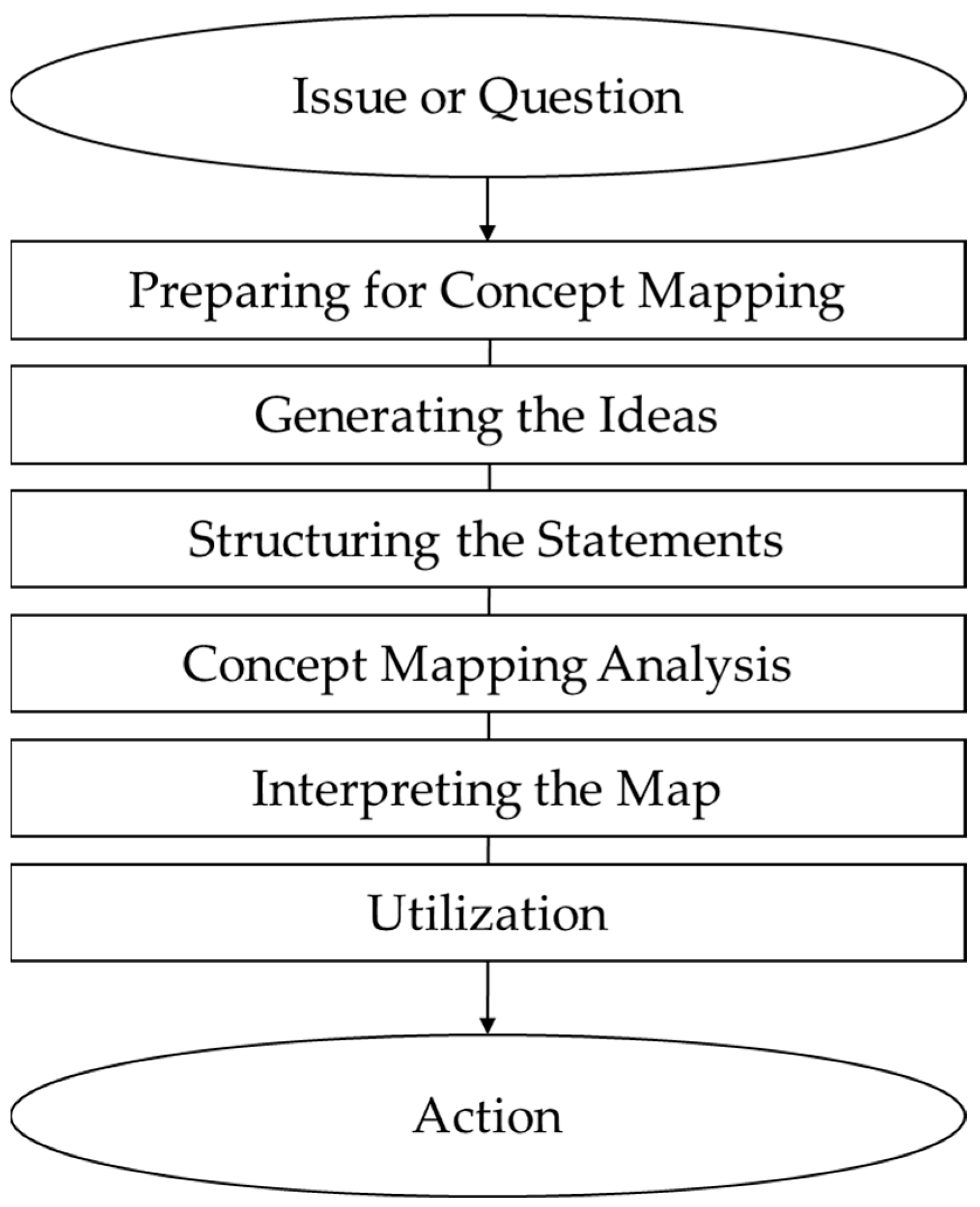

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Part 1: Generation of Healthy Eating Perceptions Statements

2.3.1. Procedure of Focus Group Interview

2.3.2. Focus Group Interview Transcripts Analysis

2.4. Part 2: Structuring Statements of Healthy Eating Perceptions

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Clustering of the Healthy Eating Perceptions

3.2. Importance and Performance of Healthy Eating Clusters

3.3. Importance and Performance of Healthy Eating Statements

4. Conclusions

4.1. Theoretical Contributions and Practical Implications

4.2. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Super, J.C. Food and history. J. Soc. Hist. 2002, 36, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Pascale, P. Consumers’ behaviours and attitudes toward healthy food products: The case of Organic and Functional foods. In Proceedings of the 113th Seminar, Crete, Greece, 3–6 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Khoo-Lattimore, C. Food and the perception of eating: The case of young Taiwanese consumers. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 1545–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, M.; Bryntorp, A.; Håkansson, A.; Höijer, K.; Olsson, V.; Rothenberg, E.; Sepp, H.; Wendin, K. Exploring the meal concept: An interdisciplinary literature overview. In Proceedings of the IX International Conference on Culinary Arts and Sciences (ICCAS), Montclair, NJ, USA, 3–5 June 2015; pp. 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Margetts, B.M.; Martinez, J.; Saba, A.; Holm, L.; Kearney, M.; Moles, A. Definitions of ‘healthy’ eating: A pan-EU survey of consumer attitudes to food, nutrition and health. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 51, S23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paquette, M.-C. Perceptions of healthy eating: State of knowledge and research gaps. Can. J. Public Health Rev. Can. Sante Publique 2005, 96, S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voytyuk, M.; Hruschka, D. Cognitive differences accounting for cross-cultural variation in perceptions of healthy eating. J. Cogn. Cult. 2017, 17, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, N.; Rajaraman, D.; Swaminathan, S.; Vaz, M.; Jayachitra, K.; Lear, S.A.; Punthakee, Z. Perceptions of healthy eating amongst Indian adolescents in India and Canada. Appetite 2017, 116, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung-Jin, J.; Ho-Jung, C. A Study on the Cookbang YouTube Program Use and Dietary Change based on the Technology Acceptance Model. Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2021, 27, 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.; Jung, M. A Convergence study on the Change of food lifestyle and kitchen environment affected by the lifestyle change: Emphasis on the single-person households. Korean Soc. Sci. Art 2021, 39, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-K.; Park, S. Emergence of internet Mukbang (Foodcasting) and its hegemonic process in media culture. Media Soc. 2016, 24, 105–150. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, J.F.; dos Santos Filho, M.T.C.; de Oliveira, L.E.A.; Siman, I.B.; de Fátima Barcelos, A.; de Paiva Anciens Ramos, G.L.; Esmerino, E.A.; da Cruz, A.G.; Arriel, R.A. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on food habits and perceptions: A study with Brazilians. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, B.; Jia, P.; Han, J. Locked on salt? Excessive consumption of high-sodium foods during COVID-19 presents an underappreciated public health risk: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 3583–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soon, J.M.; Vanany, I.; Wahab, I.R.A.; Sani, N.A.; Hamdan, R.H.; Jamaludin, M.H. Protection Motivation Theory and consumers’ food safety behaviour in response to COVID-19. Food Control 2022, 138, 109029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakalis, S.; Valdramidis, V.P.; Argyropoulos, D.; Ahrne, L.; Chen, J.; Cullen, P.J.; Cummins, E.; Datta, A.K.; Emmanouilidis, C.; Foster, T. Perspectives from CO+ RE: How COVID-19 changed our food systems and food security paradigms. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2020, 3, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Cinelli, G.; Leggeri, C.; Caparello, G.; Barrea, L.; Scerbo, F. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Choi, N.; Kim, S. A study on dietary behavior change of generation Z after COVID-19. In Proceedings of the HIC Korea 2022, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 28–30 September 2022; pp. 378–382. [Google Scholar]

- Sug-Jin, C.; Jung-Min, P.; Joo-Yeon, K. A Study on the Recognition of Government Policy and the Change of Dietary Life After COVID-19—Focusing on Economic, Psychological, and Physical Effects. J. Corp. Innov. 2022, 45, 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ammar, A.; Brach, M.; Trabelsi, K.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Masmoudi, L.; Bouaziz, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-H.; Yeon, J.-Y. Change of dietary habits and the use of home meal replacement and delivered foods due to COVID-19 among college students in Chungcheong province, Korea. J. Nutr. Health 2021, 54, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laato, S.; Islam, A.N.; Farooq, A.; Dhir, A. Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-response approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trochim, W.M. An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Eval. Program Plan. 1989, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijck, K.; Bargeman, B. The changing impact of social background on lifestyle: “culturalization” instead of individualization? Poetics 2004, 32, 447–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.; Trochim, W.M. Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Trochim, W.; Kane, M. Concept mapping: An introduction to structured conceptualization in health care. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2005, 17, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyung Hwa, M.; Yoon Jung, C. Overview of Concept Mapping in Counseling Psychology Research. Korea J. Couns. 2007, 8, 1291–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizireanu, M.; Hruschka, D. Lay perceptions of healthy eating styles and their health impacts. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 365–371.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauwerdink, A.; Kasteleyn, M.J.; Haafkens, J.A.; Chavannes, N.H.; Schijven, M.P. A national eHealth vision developed by University Medical Centres: A concept mapping study. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020, 133, 104032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svobodova, I.; Filakovska Bobakova, D.; Bosakova, L.; Dankulincova Veselska, Z. How to improve access to health care for Roma living in social exclusion: A concept mapping study. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, H.; McMurray, J.; Byrne, K.; Grindrod, K.; Stolee, P. Engagement of older adults in regional health innovation: The ECOTECH concept mapping project. SAGE Open Med. 2022, 10, 20503121211073333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaingankar, J.A.; Van Dam, R.M.; Samari, E.; Chang, S.; Seow, E.; Chua, Y.C.; Luo, N.; Verma, S.; Subramaniam, M. Social media–driven routes to positive mental health among youth: Qualitative enquiry and concept mapping study. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2022, 5, e32758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, J.; Shin, M.; Sloan, K.; Mackie, T.I.; Garcia, S.; Fehrenbacher, A.E.; Crabtree, B.F.; Palinkas, L.A. Use of concept mapping to inform a participatory engagement approach for implementation of evidence-based HPV vaccination strategies in safety-net clinics. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2024, 5, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, E.; Lahelma, E.; Virtanen, M.; Prättälä, R.; Pietinen, P. Gender, socioeconomic status and family status as determinants of food behaviour. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 46, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrell, G.; Kavanagh, A.M. Socio-economic pathways to diet: Modelling the association between socio-economic position and food purchasing behaviour. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, C.L.; Stephens, Z.P.; Cantinotti, M.; Fuller, D.; Kestens, Y.; Winters, M. Successes and failures of built environment interventions: Using concept mapping to assess stakeholder perspectives in four Canadian cities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 268, 113383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, H.; Boyland, E.J.; Scarborough, P.; Smith, R.; White, M.; Adams, J. Exploring the potential impact of the proposed UK TV and online food advertising regulations: A concept mapping study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, R.P. Concept mapping the client’s perspective on counseling alliance formation. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, H.; Mentch, L. R-CMap—An open-source software for concept mapping. Eval. Program. Plan. 2017, 60, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, J.B.; Wish, M. Multidimensional Scaling; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ishak, S.I.Z.S.; Chin, Y.S.; Taib, M.N.M.; Shariff, Z.M. Malaysian adolescents’ perceptions of healthy eating: A qualitative study. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, I.H. Motivation factors of consumers’ food choice. Food Nutr. Sci. 2016, 7, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Legrand, W.; Sloan, P. Factors influencing healthy meal choice in Germany. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2006, 54, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Haerens, L.; Craeynest, M.; Deforche, B.; Maes, L.; Cardon, G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. The contribution of psychosocial and home environmental factors in explaining eating behaviours in adolescents. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Food Literacy for Sustainable Eating; National Institute of Agricultural Sciences: Wanju-gun, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.; Park, Y.K.; Park, C.Y.; Choi, M.-K.; Shin, M.-J. Development of a comprehensive food literacy measurement tool integrating the food system and sustainability. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, C.; Doherty, G.; Barnett, J.; Muldoon, O.T.; Trew, K. Adolescents’ views of food and eating: Identifying barriers to healthy eating. J. Adolesc. 2007, 30, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L. Consumer beliefs about healthy foods and diets. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akamatsu, R.; Maeda, Y.; Hagihara, A.; Shirakawa, T. Interpretations and attitudes toward healthy eating among Japanese workers. Appetite 2005, 44, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fordyce-Voorham, S. Identification of essential food skills for skill-based healthful eating programs in secondary schools. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2011, 43, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, A.L.; Reardon, R.; McDonald, M.; Vargas-Garcia, E.J. Community interventions to improve cooking skills and their effects on confidence and eating behaviour. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2016, 5, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welfare TMoHa. General Dietary Guidelines for Koreans; The Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2016.

- Larson, N.; MacLehose, R.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Berge, J.M.; Story, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Eating breakfast and dinner together as a family: Associations with sociodemographic characteristics and implications for diet quality and weight status. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.L. Making time for family meals: Parental influences, home eating environments, barriers and protective factors. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 193, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, W.; Hong, J. IPA analysis on selection attributes of RTC (ready to cook) type milk kit HMR (home meal replacement). Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2019, 25, 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.-Y.; Kwon, Y.-S.; Park, Y.-H.; Yun, Y. Importance-performance analysis regarding selective attribution of meal-kit products. J. East. Asian Soc. Diet Life 2019, 29, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragoni-Santos, C.; Serrano Pinheiro de Souza, T.; Matheus, J.R.V.; de Brito Nogueira, T.B.; Xavier-Santos, D.; Miyahira, R.F.; Costa Antunes, A.E.; Fai, A.E.C. COVID-19 pandemic sheds light on the importance of food safety practices: Risks, global recommendations, and perspectives. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 5569–5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzay-Razaz, J.; Hassanghomi, M.; Ajami, M.; Koochakpoor, G.; Hosseini-Esfahani, F.; Mirmiran, P. Effective food hygiene principles and dietary intakes to reinforce the immune system for prevention of COVID-19: A systematic review. BMC Nutr. 2022, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, A.H.; Duarte, S.G.; Campos, G.Z.; Landgraf, M.; Franco, B.D.; Pinto, U.M. Food safety issues related to eating in and eating out. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.; White, M.; Brown, H.; Wrieden, W.; Kwasnicka, D.; Halligan, J.; Robalino, S.; Adams, J. Health and social determinants and outcomes of home cooking: A systematic review of observational studies. Appetite 2017, 111, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladele, O.; Akinsorotan, O. Effect of Genetically Modified Organisms (Gmos) on Health and Environment in Southwestern Nigeria: Scientists’ Perception. J. Agric. Ext. 2007, 10, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalakshmi, K.; Prasad, V.S.; Nithyasri, M.; Geetha, B. A Study on Consumer Behaviour Towards Instant Food Products. YMER 2024, 23, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Sadler, C.R.; Grassby, T.; Hart, K.; Raats, M.M.; Sokolović, M.; Timotijevic, L. “Even we are confused”: A thematic analysis of Professionals’ perceptions of processed foods and challenges for communication. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 826162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floros, J.D.; Newsome, R.; Fisher, W.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V.; Chen, H.; Dunne, C.P.; German, J.B.; Hall, R.L.; Heldman, D.R.; Karwe, M.V. Feeding the world today and tomorrow: The importance of food science and technology: An IFT scientific review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2010, 9, 572–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machín, L.; Antúnez, L.; Curutchet, M.R.; Ares, G. The heuristics that guide healthiness perception of ultra-processed foods: A qualitative exploration. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 2932–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA. Food safety in the EU. In Special Eurobarometer 913; European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Soliah, L.A.L.; Walter, J.M.; Jones, S.A. Benefits and barriers to healthful eating: What are the consequences of decreased food preparation ability? Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2012, 6, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachat, C.; Nago, E.; Verstraeten, R.; Roberfroid, D.; Van Camp, J.; Kolsteren, P. Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: A systematic review of the evidence. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 329–346. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, N.; Ishitsuka, K.; Piedvache, A.; Tanaka, H.; Murayama, N.; Morisaki, N. Convenience Food Options and Adequacy of Nutrient Intake among School Children during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2022, 14, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, L.; de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Labesse, M.; Nicklaus, S. Food choice motives and the nutritional quality of diet during the COVID-19 lockdown in France. Appetite 2021, 157, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beydoun, M.A.; Powell, L.M.; Wang, Y. Reduced away-from-home food expenditure and better nutrition knowledge and belief can improve quality of dietary intake among US adults. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poti, J.M.; Mendez, M.A.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B.M. Is the degree of food processing and convenience linked with the nutritional quality of foods purchased by US households? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Steele, E.; Popkin, B.M.; Swinburn, B.; Monteiro, C.A. The share of ultra-processed foods and the overall nutritional quality of diets in the US: Evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Popul. Health Metr. 2017, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S. Effects of Recognition of Korean food on the Attitude and Intention of Behavior. Foodserv. Ind. J. 2017, 13, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, E.S.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y. Trends in sodium intake and major contributing food groups and dishes in Korea: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013–2017. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2021, 15, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Freeland-Graves, J.H.; Kim, H.J. Nineteen-year trends in fermented food consumption and sodium intake from fermented foods for Korean adults from 1998 to 2016. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffond, A.; Rivera-Picón, C.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, P.M.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Ruiz de Viñaspre-Hernández, R.; Navas-Echazarreta, N.; Sánchez-González, J.L. Mediterranean diet for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and mortality: An updated systematic review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghadir, A.H.; Iqbal, Z.A.; A Gabr, S. The relationships of watching television, computer use, physical activity, and food preferences to body mass index: Gender and nativity differences among adolescents in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Roso, M.B.; de Carvalho Padilha, P.; Mantilla-Escalante, D.C.; Ulloa, N.; Brun, P.; Acevedo-Correa, D.; Arantes Ferreira Peres, W.; Martorell, M.; Aires, M.T.; de Oliveira Cardoso, L. COVID-19 confinement and changes of adolescent’s dietary trends in Italy, Spain, Chile, Colombia and Brazil. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werneck, A.O.; Silva, D.R.; Malta, D.C.; Gomes, C.S.; Souza-Júnior, P.R.; Azevedo, L.O.; Barros, M.B.; Szwarcwald, C.L. Associations of sedentary behaviours and incidence of unhealthy diet during the COVID-19 quarantine in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.T.; Tan, S.S.; Tan, C.X. Screen time-based sedentary behaviour, eating regulation and weight status of university students during the COVID-19 lockdown. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 52, 281–291. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz, K.; Basil, M.; Maibach, E.; Goldberg, J.; Snyder, D. Why Americans eat what they do: Taste, nutrition, cost, convenience, and weight control concerns as influences on food consumption. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1998, 98, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.G.; Bond, D.S. Review of innovations in digital health technology to promote weight control. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2014, 14, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, C.; Poltawski, L.; Garside, R.; Briscoe, S. Understanding the challenge of weight loss maintenance: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research on weight loss maintenance. Health Psychol. Rev. 2017, 11, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.-J.; Park, K.-Y. Investigative Study on the Establishing of Range of Eating-out and Criterion for Assortment of Foodservice Industry by Standard Industrial Classification. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2007, 19, 389–406. [Google Scholar]

- Lê, J.; Dallongeville, J.; Wagner, A.; Arveiler, D.; Haas, B.; Cottel, D.; Simon, C.; Dauchet, L. Attitudes toward healthy eating: A mediator of the educational level–diet relationship. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Inayama, T.; Hata, K.; Matsushita, M.; Takahashi, M.; Harada, K.; Arao, T. Association of household income and education with eating behaviors in Japanese adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2015, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Cluster | Importance Mean ± SD | Performance Mean ± SD | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food choice | 3.96 ± 0.51 | 3.22 ± 0.55 | 5.490 *** (1) |

| Nutrition | 3.99 ± 0.50 | 3.08 ± 0.33 | 7.036 *** |

| Eating habits | 3.62 ± 0.51 | 3.03 ± 0.56 | 4.390 *** |

| Eating environment | 3.58 ± 0.57 | 3.36 ± 0.36 | 1.745 NS (2) |

| Production | 3.76 ± 0.73 | 3.11 ± 0.74 | 4.609 *** |

| Preparation and cooking | 3.50 ± 0.43 | 3.26 ± 0.51 | 2.354 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeo, G.; Oh, J. Perceptions Regarding Healthy Eating Based on Concept Mapping. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2941. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182941

Yeo G, Oh J. Perceptions Regarding Healthy Eating Based on Concept Mapping. Nutrients. 2025; 17(18):2941. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182941

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeo, Gaeun, and Jieun Oh. 2025. "Perceptions Regarding Healthy Eating Based on Concept Mapping" Nutrients 17, no. 18: 2941. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182941

APA StyleYeo, G., & Oh, J. (2025). Perceptions Regarding Healthy Eating Based on Concept Mapping. Nutrients, 17(18), 2941. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182941