The Influence of Parental Control on Emotional Eating Among College Students: The Mediating Role of Emotional Experience and Regulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Emotional Eating

1.2. Parental Control and Emotional Eating

1.3. The Relationship Between Negative Emotions, Parental Control, and Emotional Eating

1.4. The Relationship Between Emotion Regulation Strategies, Parental Control, and Emotional Eating

- 1.

- Both parental behavioral control and psychological control are significantly associated with emotional eating, but do their effects align?

- 2.

- Do negative emotions mediate the relationship between parental control and emotional eating?

- 3.

- Do emotion regulation strategies mediate the relationship between parental control and emotional eating?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.2. Participants

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. Parental Control

2.3.2. Emotion Regulation Strategies

2.3.3. Negative Emotion

2.3.4. Emotional Eating

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.2. Mediation Effect Test

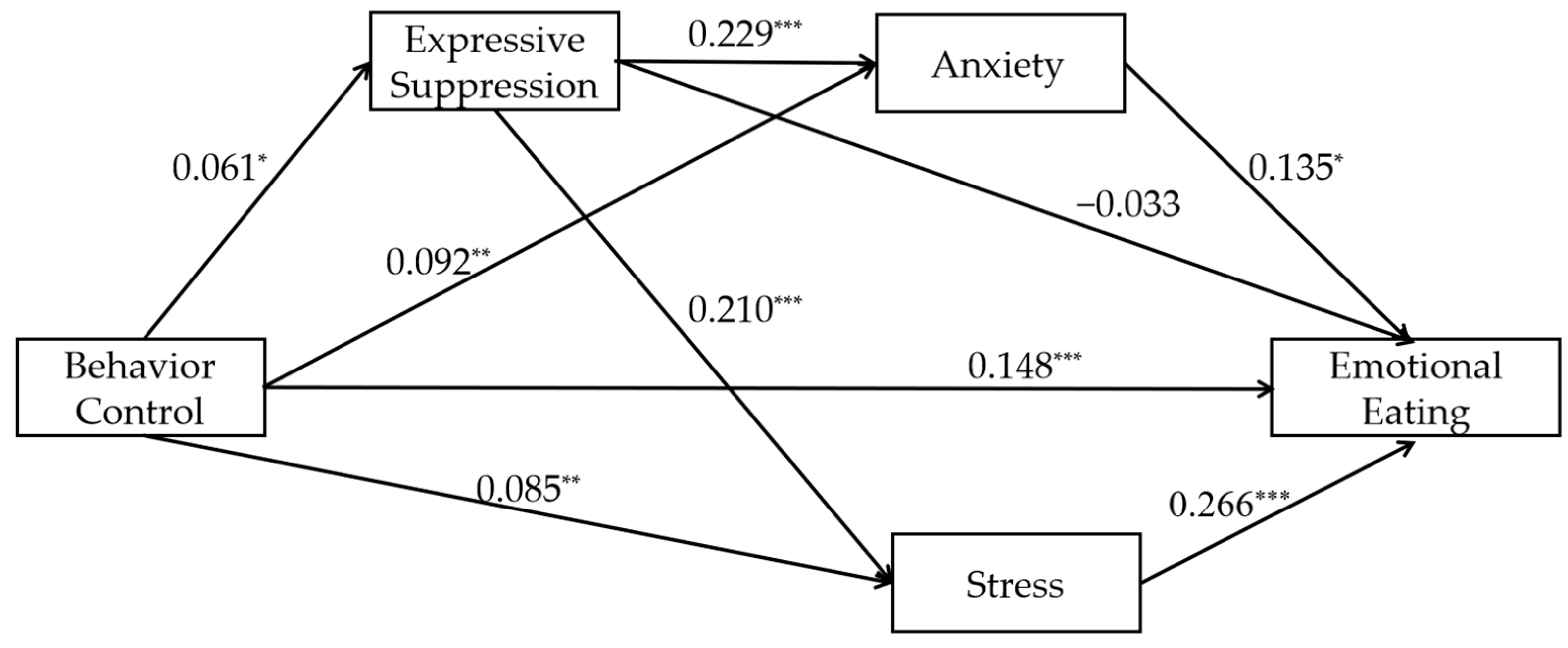

3.2.1. The Relationship Between Parental Behavioral Control and Emotional Eating Mediated by Expressive Suppression and Negative Emotions (Model 1)

3.2.2. The Relationship Between Parental Behavioral Control and Emotional Eating Mediated by Cognitive Reappraisal and Negative Emotions (Model 2)

3.2.3. The Relationship Between Parental Psychological Control and Emotional Eating Mediated by Cognitive Reappraisal and Negative Emotions (Model 3)

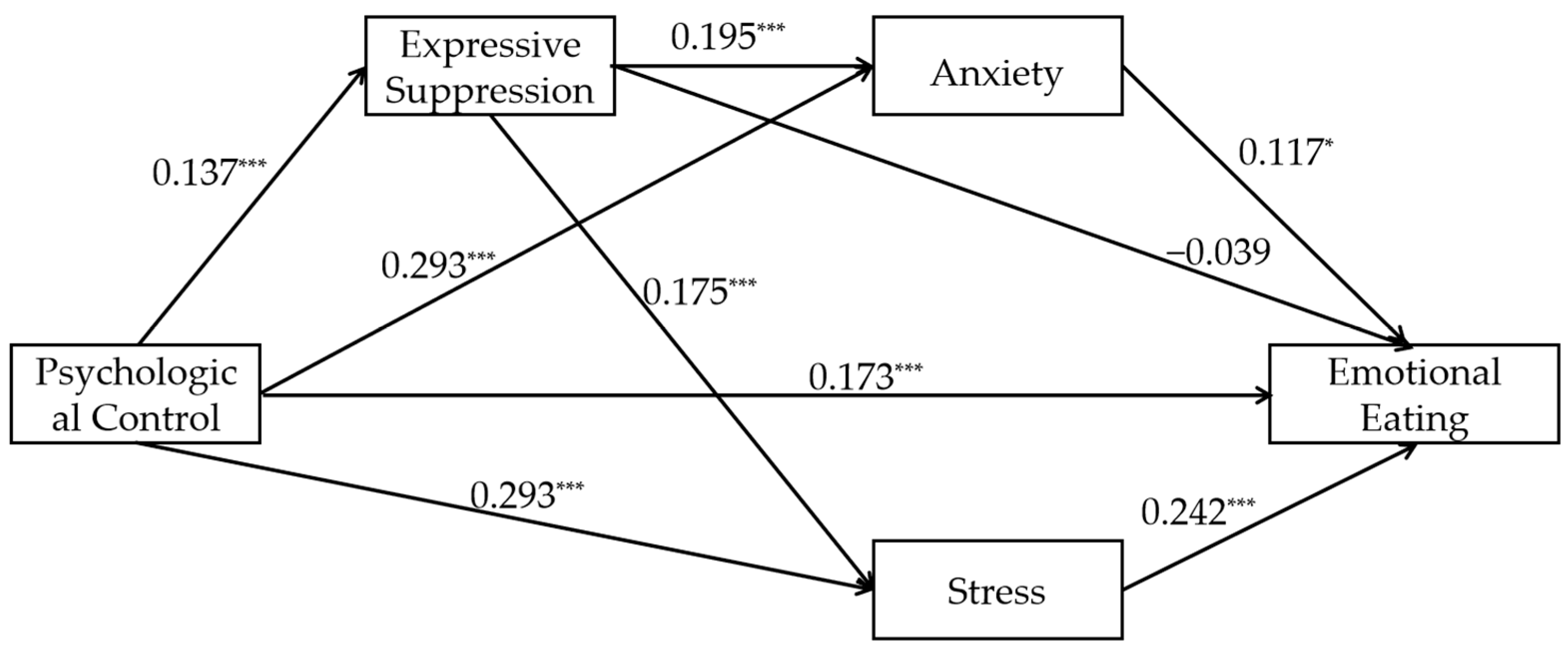

3.2.4. The Relationship Between Parental Psychological Control and Emotional Eating Mediated by Expressive Suppression and Negative Emotions (Model 4)

4. Discussion

4.1. Parental Control and Emotional Eating

4.2. Mediating Effects of Negative Emotions and Emotion Regulation Strategies

4.3. Research Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jun, S.; Choi, E. Academic Stress and Internet Addiction from General Strain Theory Framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 49, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, H.; Tian, E.; Su, X.; Su, S.; Zhou, W.; Gao, Y. The Influence of Physical Exercise on Adolescents’ Negative Emotions: The Chain Mediating Role of Academic Stress and Sleep Quality. BMC Pediatr. 2025, 25, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y. How Do Academic Stress and Leisure Activities Influence College Students’ Emotional Well-Being? A Daily Diary Investigation. J. Adolesc. 2017, 60, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, L.; Braet, C.; Van Vlierberghe, L.; Mels, S. Loss of Control over Eating in Overweight Youngsters: The Role of Anxiety, Depression and Emotional Eating. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2009, 17, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macht, M. How Emotions Affect Eating: A Five-Way Model. Appetite 2008, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolz, I.; Biehl, S.; Svaldi, J. Emotional Reactivity, Suppression of Emotions and Response Inhibition in Emotional Eaters: A Multi-Method Pilot Study. Appetite 2021, 161, 105142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Strien, T.; Van De Laar, F.A.; Van Leeuwe, J.F.J.; Lucassen, P.L.B.J.; Van Den Hoogen, H.J.M.; Rutten, G.E.H.M.; Van Weel, C. The Dieting Dilemma in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes: Does Dietary Restraint Predict Weight Gain 4 Years after Diagnosis? Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Strien, T.; Cebolla, A.; Etchemendy, E.; Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J.; Ferrer-García, M.; Botella, C.; Baños, R. Emotional Eating and Food Intake after Sadness and Joy. Appetite 2013, 66, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macht, M.; Haupt, C.; Ellgring, H. The Perceived Function of Eating Is Changed during Examination Stress: A Field Study. Eat. Behav. 2005, 6, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, T.C.; Epel, E.S. Stress, Eating and the Reward System. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 91, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, Z.; Cagatay, S.E. Childhood Traumas and Emotional Eating: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem, and Emotion Dysregulation. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 21783–21791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganley, R.M. Emotion and Eating in Obesity: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1989, 8, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braet, C.; Claus, L.; Goossens, L.; Moens, E.; Van Vlierberghe, L.; Soetens, B. Differences in Eating Style between Overweight and Normal-Weight Youngsters. J. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, W.R.; Braden, A.L.; Jordan, A.K. Negative and Positive Emotional Eating Uniquely Interact with Ease of Activation, Intensity, and Duration of Emotional Reactivity to Predict Increased Binge Eating. Appetite 2020, 151, 104688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongers, P.; Jansen, A. Emotional Eating and Pavlovian Learning: Evidence for Conditioned Appetitive Responding to Negative Emotional States. Cogn. Emot. 2017, 31, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawner, L.R.; Filippetti, M.L. A Developmental Model of Emotional Eating. Dev. Rev. 2024, 72, 101133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscatelli, F.; De Maria, A.; Marinaccio, L.A.; Monda, V.; Messina, A.; Monacis, D.; Toto, G.; Limone, P.; Monda, M.; Messina, G.; et al. Assessment of Lifestyle, Eating Habits and the Effect of Nutritional Education among Undergraduate Students in Southern Italy. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-674-22456-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, L.; Wu, W. Parenting Styles, Empathy and Aggressive Behavior in Preschool Children: An Examination of Mediating Mechanisms. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1243623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, K.; Hou, J.; Jiang, L.; Chen, Z. The Influence of Parental Rearing Styles on Adolescent Trait Anxiety: The Mediating Role of Volitional Control. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 27, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, A. Negative Parenting Styles and Psychological Crisis in Adolescents: Testing a Moderated Mediating Model of School Connectedness and Self-Esteem. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, L.-M.; Ogielda, C.; Rowse, G. The Role of Experiential Avoidance and Parental Control in the Association Between Parent and Child Anxiety. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, Y. Examining the Subjective Well-Being of Adolescents in Terms of Demographic Variables, Parental Control, and Parental Warmth. Egit. Bilim 2012, 37, 20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B.K.; Olsen, J.E.; Shagle, S.C. Associations between Parental Psychological and Behavioral Control and Youth Internalized and Externalized Behaviors. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerantz, E.M.; Wang, Q. The Role of Parental Control in Children’s Development in Western and East Asian Countries. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.K. Parental Psychological Control: Revisiting a Neglected Construct. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Zhang, W.; Dong, Y.; Chen, G. Parental Control and Adolescent Social Anxiety: A Focus on Emotional Regulation Strategies and Socioeconomic Influences in China. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2025, 43, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Luo, X.; Cai, T.; Li, Z.; Liu, W. Self-Control and Parental Control Mediate the Relationship between Negative Emotions and Emotional Eating among Adolescents. Appetite 2014, 82, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, H. The Roles of Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies and Punishment Sensitivity in the Relationship Between Parental Psychological Control and Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 30, 1192–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoek, H.M.; Engels, R.C.M.E.; Janssens, J.M.A.M.; Van Strien, T. Parental Behaviour and Adolescents’ Emotional Eating. Appetite 2007, 49, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwairy, M.; Achoui, M. Parental Control: A Second Cross-Cultural Research on Parenting and Psychological Adjustment of Children. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2010, 19, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.K.; Stolz, H.E.; Olsen, J.A.; Collins, W.A.; Burchinal, M. Parental Support, Psychological Control, and Behavioral Control: Assessing Relevance across Time, Culture, and Method. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2005, 70, i+v+vii+1–147. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Li, D.; Newman, J. Parental Behavioral and Psychological Control and Problematic Internet Use Among Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Self-Control. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanovic, S.; Boele, S.; Skoog, T. Parent-Adolescent Communication and Adolescent Delinquency: Unraveling Within-Family Processes from Between-Family Differences. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 1707–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harma, M.; Aktaş, B.; Sümer, N. Behavioral but Not Psychological Control Predicts Self-Regulation, Adjustment Problems and Academic Self-Efficacy Among Early Adolescents. J. Psychol. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Chen, H. The Role of Parents’ Control in Early Adolescents’ Psychological Functioning: A Longitudinal Investigation in the United States and China. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 1592–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgardner, M.; Boyatzis, C.J. The Role of Parental Psychological Control and Warmth in College Students’ Relational Aggression and Friendship Quality. Emerg. Adulthood 2018, 6, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J.E. Annual Research Review: Cross-Cultural Similarities and Differences in Parenting. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 63, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Nie, X.; Zhang, D.; Hu, Y. The Relationship between Parental Psychological Control and Problematic Smartphone Use in Early Chinese Adolescence: A Repeated-Measures Study at Two Time-Points. Addict. Behav. 2022, 125, 107142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Teng, Z.; Li, Y.; Cui, H.; Nie, Q. The Longitudinal Relationship Between Parental Psychological Control, Depression Symptoms in High School Students, and Their Sense of Life Meaning: A Cross-Lagged Model Analysis. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2025, 5, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Bloemer, A.C.; Palazzo, C.C.; Diez-Garcia, R.W. Relationship of Negative Emotion with Leptin and Food Intake among Overweight Women. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 237, 113457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, K.E.; Ruzicka, E.B.; Fahrenkamp, A.J.; Sato, A.F. Perceived Stress and Obesity-Promoting Eating Behaviors in Adolescence: The Role of Parent-Adolescent Conflict. Fam. Syst. Health 2019, 37, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.; Limbers, C.A. Avoidant Coping Moderates the Relationship between Stress and Depressive Emotional Eating in Adolescents. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2017, 22, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarevich, I.; Irigoyen Camacho, M.E.; Velázquez-Alva, M.D.C.; Zepeda Zepeda, M. Relationship among Obesity, Depression, and Emotional Eating in Young Adults. Appetite 2016, 107, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Rodriguez, S.T.; Unger, J.B.; Spruijt-Metz, D. Psychological Determinants of Emotional Eating in Adolescence. Eat. Disord. 2009, 17, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Current Status and Future Prospects. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Affective, Cognitive, and Social Consequences. Psychophysiology 2002, 39, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Mistry, R.; Ran, G.; Wang, X. Relation between Emotion Regulation and Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis Review. Psychol. Rep. 2014, 114, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haga, S.M.; Kraft, P.; Corby, E.-K. Emotion Regulation: Antecedents and Well-Being Outcomes of Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression in Cross-Cultural Samples. J. Happiness Stud. 2009, 10, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. Healthy and Unhealthy Emotion Regulation: Personality Processes, Individual Differences, and Life Span Development. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 1301–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual Differences in Two Emotion Regulation Processes: Implications for Affect, Relationships, and Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erzi, S.; Eksi, H. Parental Control and Relational Aggression in Adolescence: Mediator Role of Emotion Regulation. Cyprus Turk. J. Psychiatry Psychol. 2021, 3, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.S.; Criss, M.M.; Silk, J.S.; Houltberg, B.J. The Impact of Parenting on Emotion Regulation During Childhood and Adolescence. Child Dev. Perspect. 2017, 11, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Wang, C. Interactive Effects of Parental Psychological Control and Autonomy Support on Emerging Adults’ Emotion Regulation and Self-Esteem. Curr Psychol 2023, 42, 16111–16120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.H.; Jue, J. The Mediating Effect of Emotion Inhibition and Emotion Regulation Between Adolescents’ Perceived Parental Psychological Control and Depression. Sage Open 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar, A.; Battams, F. Emotion Regulation in Emerging Adults: Do Parenting And Parents’ Own Emotion Regulation Matter? J. Adult Dev. 2023, 30, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shriver, L.H.; Dollar, J.M.; Calkins, S.D.; Keane, S.P.; Shanahan, L.; Wideman, L. Emotional Eating in Adolescence: Effects of Emotion Regulation, Weight Status and Negative Body Image. Nutrients 2021, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnhart, W.R.; Braden, A.L.; Dial, L.A. Emotion Regulation Difficulties Strengthen Relationships Between Perceived Parental Feeding Practices and Emotional Eating: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2021, 28, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M.; Ayduk, O. Conceal and Don’t Feel as Much? Experiential Effects of Expressive Suppression. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2024, 01461672241290397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandewalle, J.; Moens, E.; Braet, C. Comprehending Emotional Eating in Obese Youngsters: The Role of Parental Rejection and Emotion Regulation. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 38, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berinsky, A.J.; Frydman, A.; Margolis, M.F.; Sances, M.W.; Valerio, D.C. Measuring Attentiveness in Self-Administered Surveys. Public Opin. Q. 2024, 88, 214–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhao, W.; Chen, J.; Li, Z. The independent effects of parental behavioral control and psychological control on adolescent online gaming addiction and their mechanisms. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 31, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H. Personality traits and subjective well-being: The mediating role of emotional regulation. J. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 33, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, M.M.; Bieling, P.J. Psychometric Properties of the 42-Item and 21-Item Versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in Clinical Groups and a Community Sample. Psychol. Assess. 1998, 10, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yu, H.; Zeng, W.; Wei, C.; Wang, Y. The mediating role of psychological resilience between the Big Five personality traits and depression, anxiety, and stress among officers and enlisted personnel in surface naval forces. Occup. Health 2023, 39, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Strien, T.; Frijters, J.E.R.; Bergers, G.P.A.; Defares, P.B. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for Assessment of Restrained, Emotional, and External Eating Behavior. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Bao, J. The applicability of the Chinese version of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire among Chinese college students. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 26, 277–281, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Methodology in the social sciences; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-60918-230-4. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional eating | 2.468 | 0.865 | — | ||||||

| 2. Cognitive reappraisal | 5.213 | 0.767 | −0.038 | — | |||||

| 3. Expressive suppression | 3.870 | 1.204 | 0.063 * | −0.004 | — | ||||

| 4. Depression | 1.772 | 0.579 | 0.329 ** | −0.321 ** | 0.259 ** | — | |||

| 5. Anxiety | 1.929 | 0.572 | 0.365 ** | −0.254 ** | 0.235 ** | 0.812 ** | — | ||

| 6. Stress | 2.098 | 0.611 | 0.387 ** | −0.270 ** | 0.217 ** | 0.798 ** | 0.844 ** | — | |

| 7. Psychological control | 2.761 | 0.876 | 0.284 ** | −0.024 | 0.138 ** | 0.326 ** | 0.321 ** | 0.317 ** | — |

| 8. Behavior control | 3.100 | 0.694 | 0.185 ** | 0.148 ** | 0.059 * | 0.070 * | 0.106 ** | 0.098 ** | 0.485 ** |

| Path | Effect Value | Effect Size (%) | SE | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| Direct effect | 0.148 | 79.570 | 0.027 | 0.095 | 0.200 |

| Ind1 | −0.002 | −1.075 | 0.002 | −0.007 | 0.002 |

| Ind2 | 0.012 | 6.452 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.027 |

| Ind3 | 0.023 | 12.366 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.043 |

| Ind4 | 0.002 | 1.075 | 0.001 | −0.000 | 0.005 |

| Ind5 | 0.003 | 1.613 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.008 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.038 | 20.430 | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.062 |

| Total effect | 0.186 | 0.029 | 0.129 | 0.242 | |

| Path | Effect Value | Effect Size (%) | SE | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| Direct effect | 0.138 | 74.194 | 0.027 | 0.085 | 0.192 |

| Ind1 | 0.007 | 3.763 | 0.005 | −0.002 | 0.017 |

| Ind2 | 0.020 | 10.753 | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.039 |

| Ind3 | 0.039 | 20.968 | 0.011 | 0.019 | 0.063 |

| Ind4 | −0.006 | −3.226 | 0.003 | −0.011 | −0.001 |

| Ind5 | −0.012 | −6.452 | 0.004 | −0.020 | −0.006 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.048 | 25.806 | 0.013 | 0.022 | 0.074 |

| Total effect | 0.186 | 0.029 | 0.129 | 0.242 | |

| Path | Effect Value | Effect Size (%) | SE | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| Direct effect | 0.162 | 58.696 | 0.028 | 0.108 | 0.216 |

| Ind1 | −0.001 | −0.362 | 0.002 | −0.006 | 0.002 |

| Ind2 | 0.036 | 13.043 | 0.017 | 0.003 | 0.070 |

| Ind3 | 0.077 | 27.899 | 0.018 | 0.043 | 0.114 |

| Ind4 | 0.001 | 0.362 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.003 |

| Ind5 | 0.001 | 0.362 | 0.002 | −0.003 | 0.006 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.113 | 40.942 | 0.015 | 0.089 | 0.146 |

| Total effect | 0.276 | 0.028 | 0.222 | 0.330 | |

| Path | Effect Value | Effect Size (%) | SE | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| Direct effect | 0.169 | 61.232 | 0.028 | 0.115 | 0.223 |

| Ind1 | −0.005 | −1.812 | 0.004 | −0.014 | 0.003 |

| Ind2 | 0.034 | 12.319 | 0.016 | 0.002 | 0.067 |

| Ind3 | 0.069 | 25.000 | 0.018 | 0.002 | 0.067 |

| Ind4 | 0.003 | 1.087 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.007 |

| Ind5 | 0.006 | 2.174 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.011 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.106 | 38.406 | 0.015 | 0.079 | 0.136 |

| Total effect | 0.276 | 0.028 | 0.222 | 0.330 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Jing, Y.; Song, S. The Influence of Parental Control on Emotional Eating Among College Students: The Mediating Role of Emotional Experience and Regulation. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2756. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172756

Wang L, Jing Y, Song S. The Influence of Parental Control on Emotional Eating Among College Students: The Mediating Role of Emotional Experience and Regulation. Nutrients. 2025; 17(17):2756. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172756

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Leran, Yuanluo Jing, and Shiqing Song. 2025. "The Influence of Parental Control on Emotional Eating Among College Students: The Mediating Role of Emotional Experience and Regulation" Nutrients 17, no. 17: 2756. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172756

APA StyleWang, L., Jing, Y., & Song, S. (2025). The Influence of Parental Control on Emotional Eating Among College Students: The Mediating Role of Emotional Experience and Regulation. Nutrients, 17(17), 2756. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172756