Consumption of 100% Juice and Diluted 100% Juice Is Associated with Better Compliance with Dietary Guidelines for Americans: Analyses of NHANES 2017–2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population Data and Surveys

2.2. Participant Characteristics

2.3. Classification of Beverages

2.4. Healthy Eating Index 2020 and Nutrient Rich Food Index

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the NHANES Sample

3.2. Consumers and Non-Consumers of 100% Juice and Diluted 100% Juice

3.3. Distribution of Beverage Consumption by Age Group

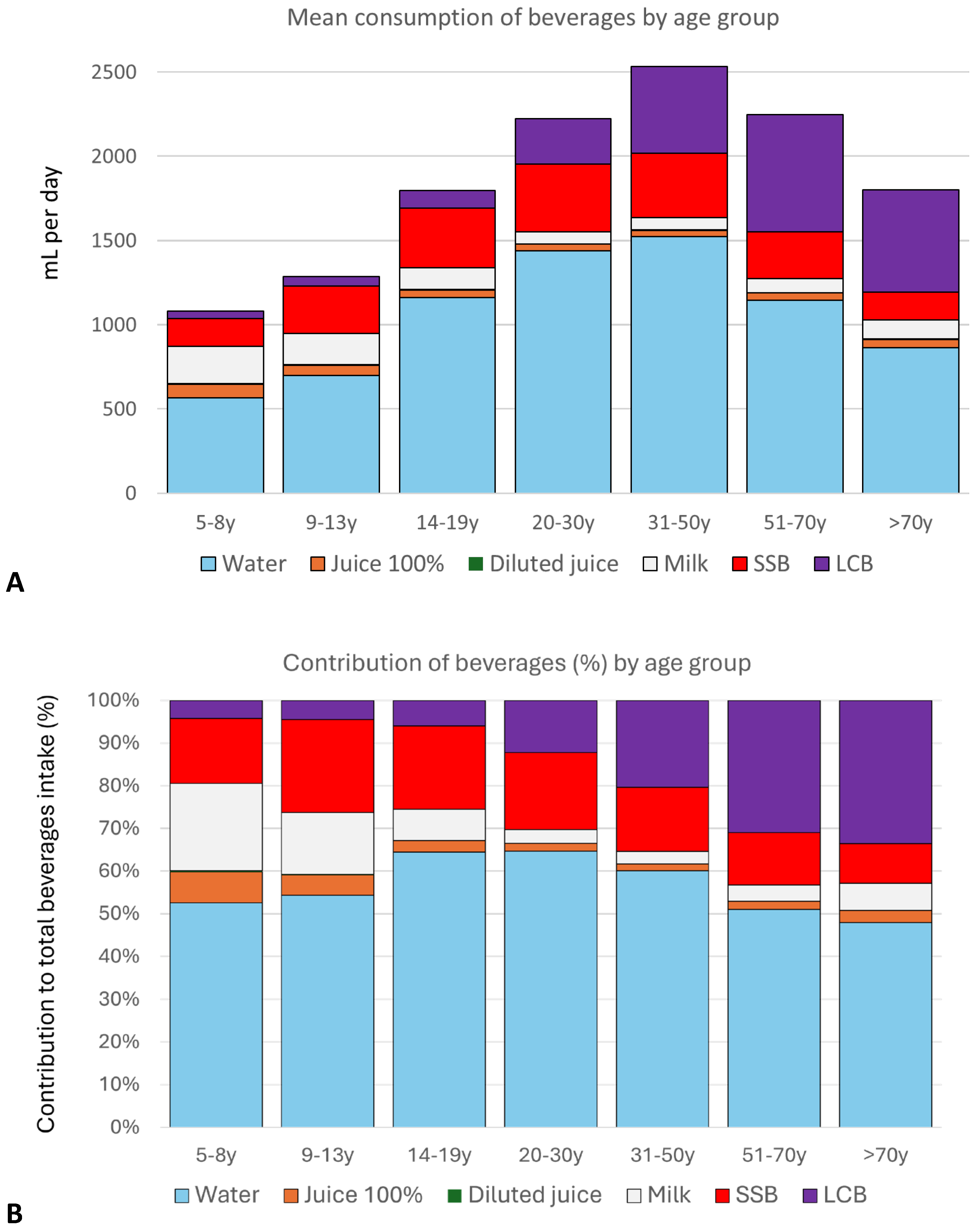

3.4. Distribution of Beverage Consumption by Socio-Demographics

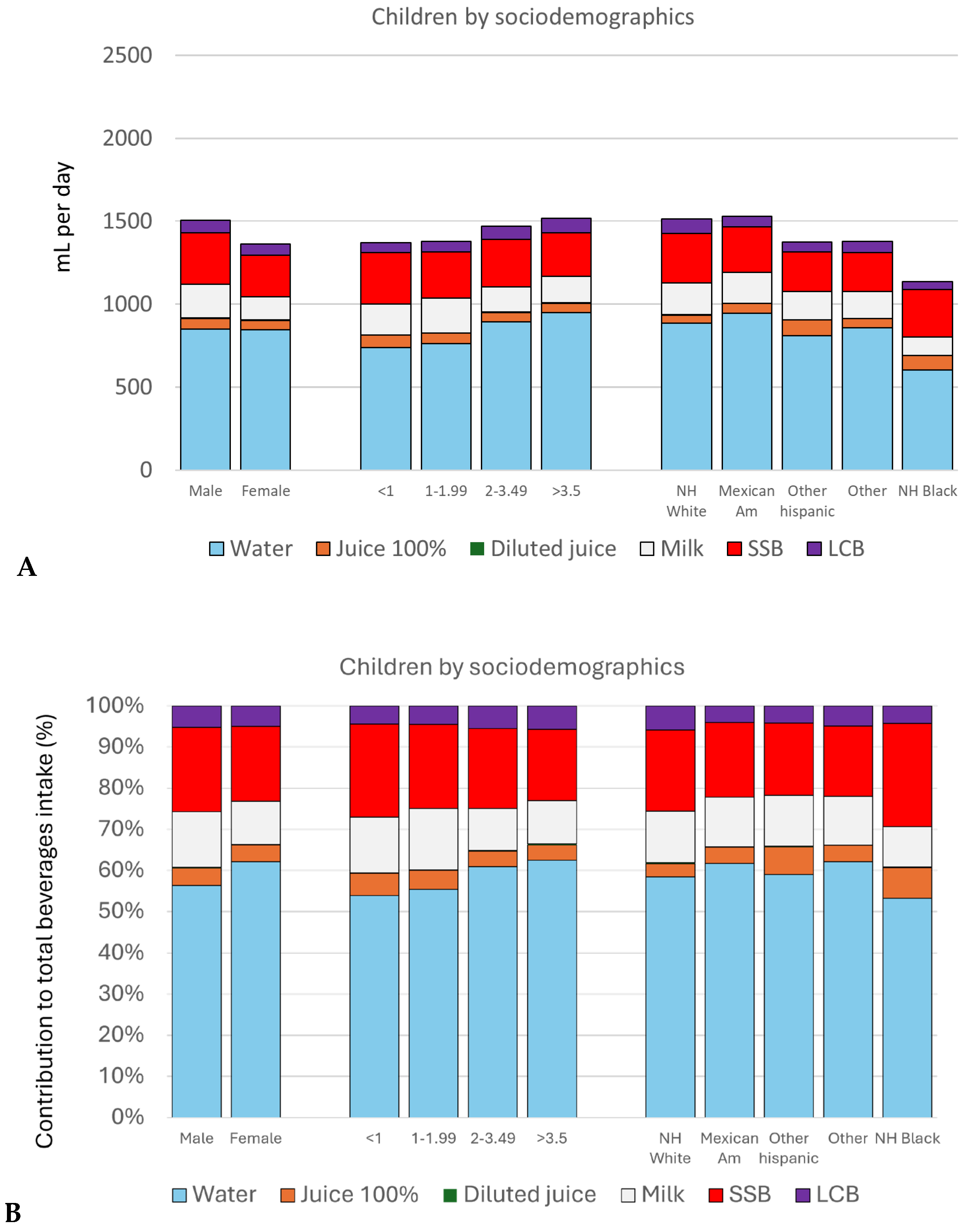

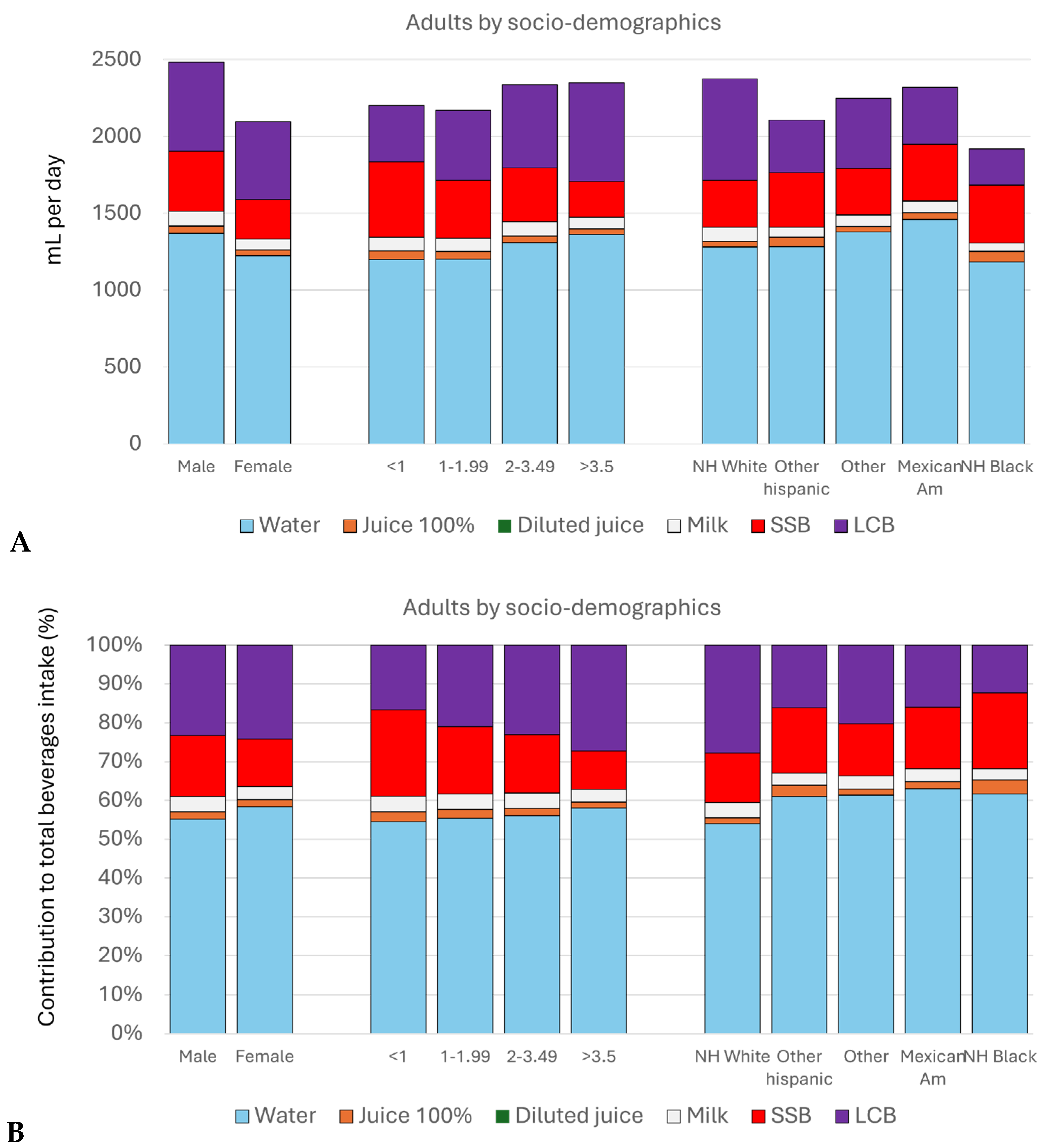

3.5. Compliance with the 100% Juice/Whole Fruit Ratio in the DGA

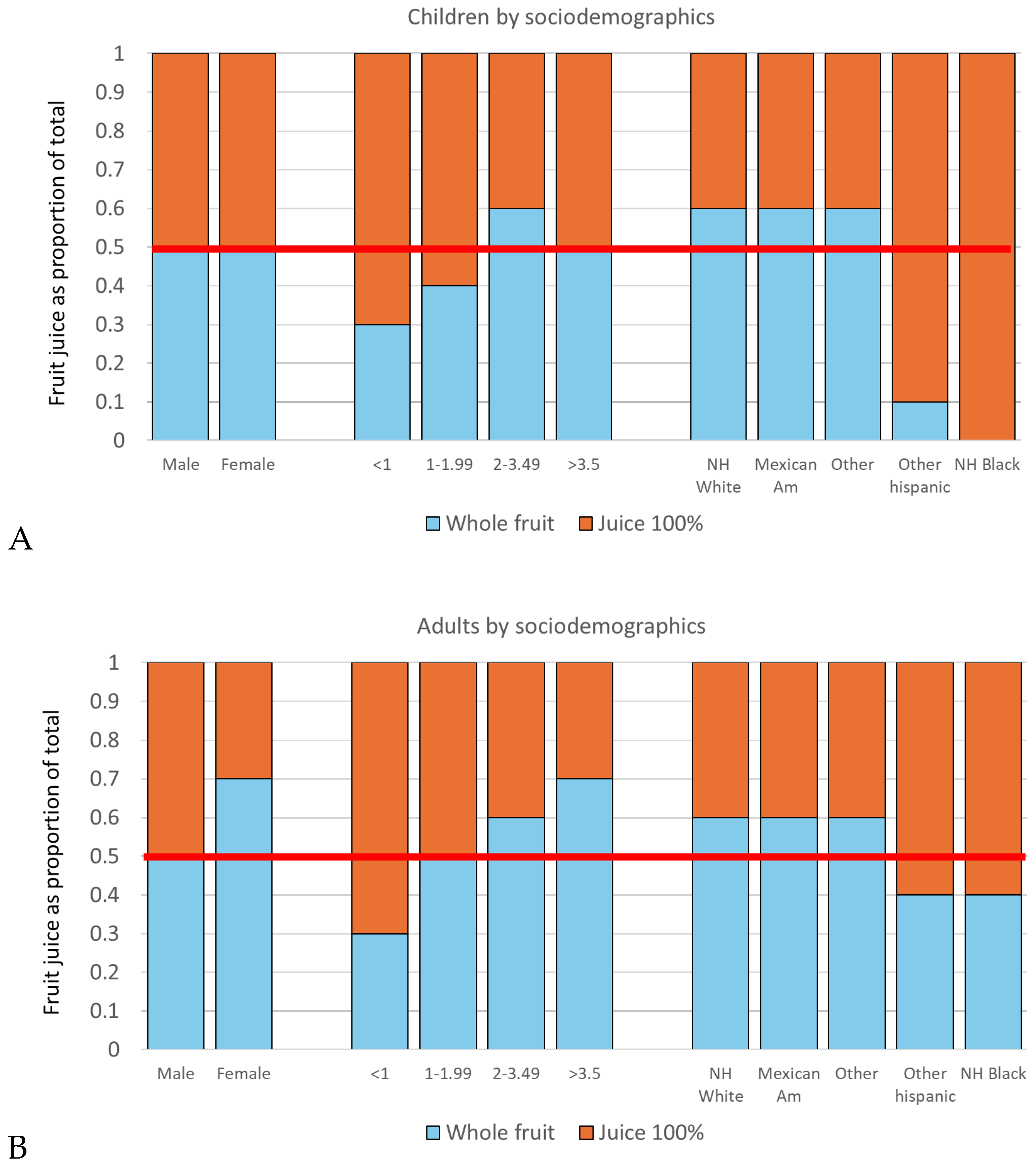

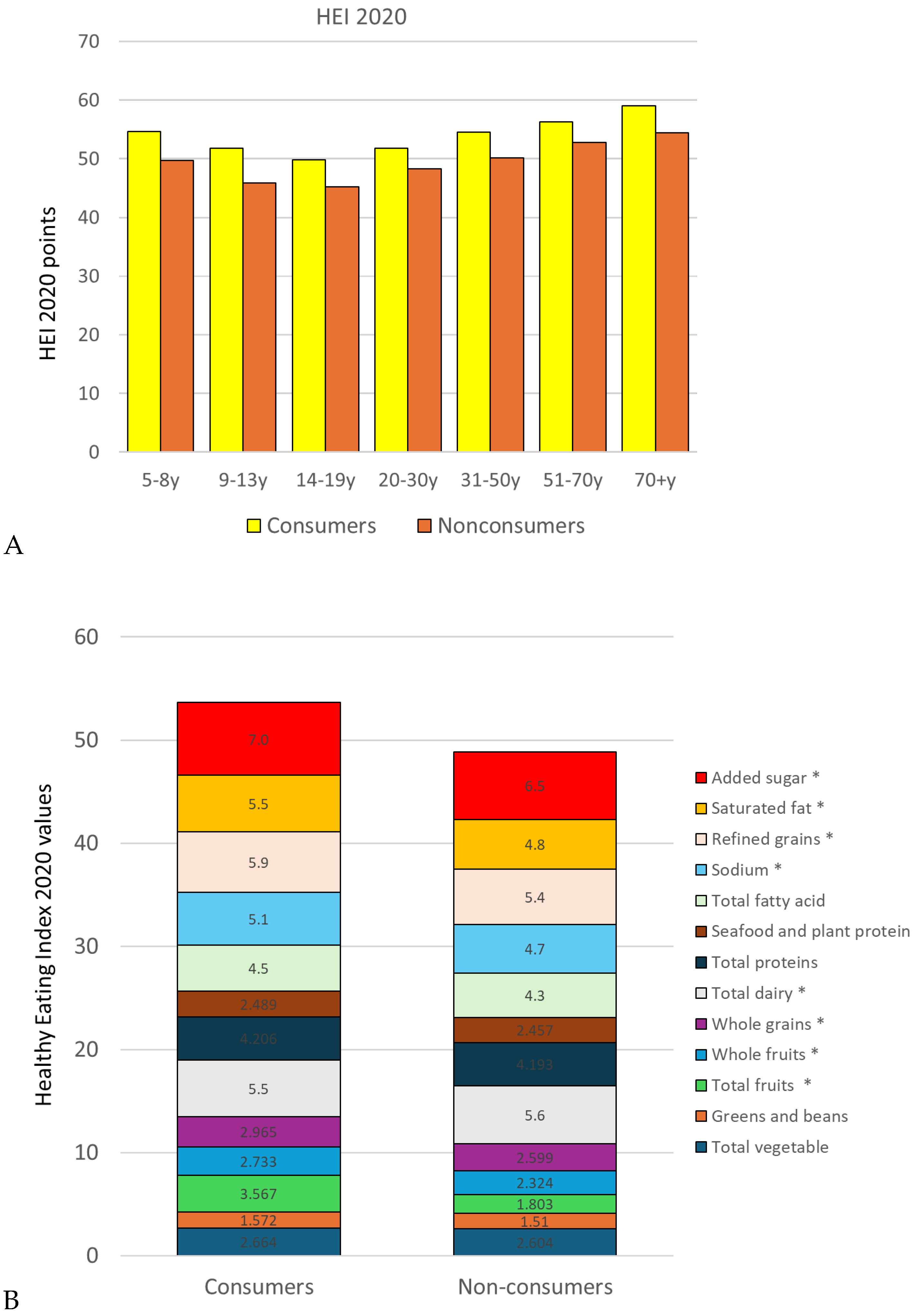

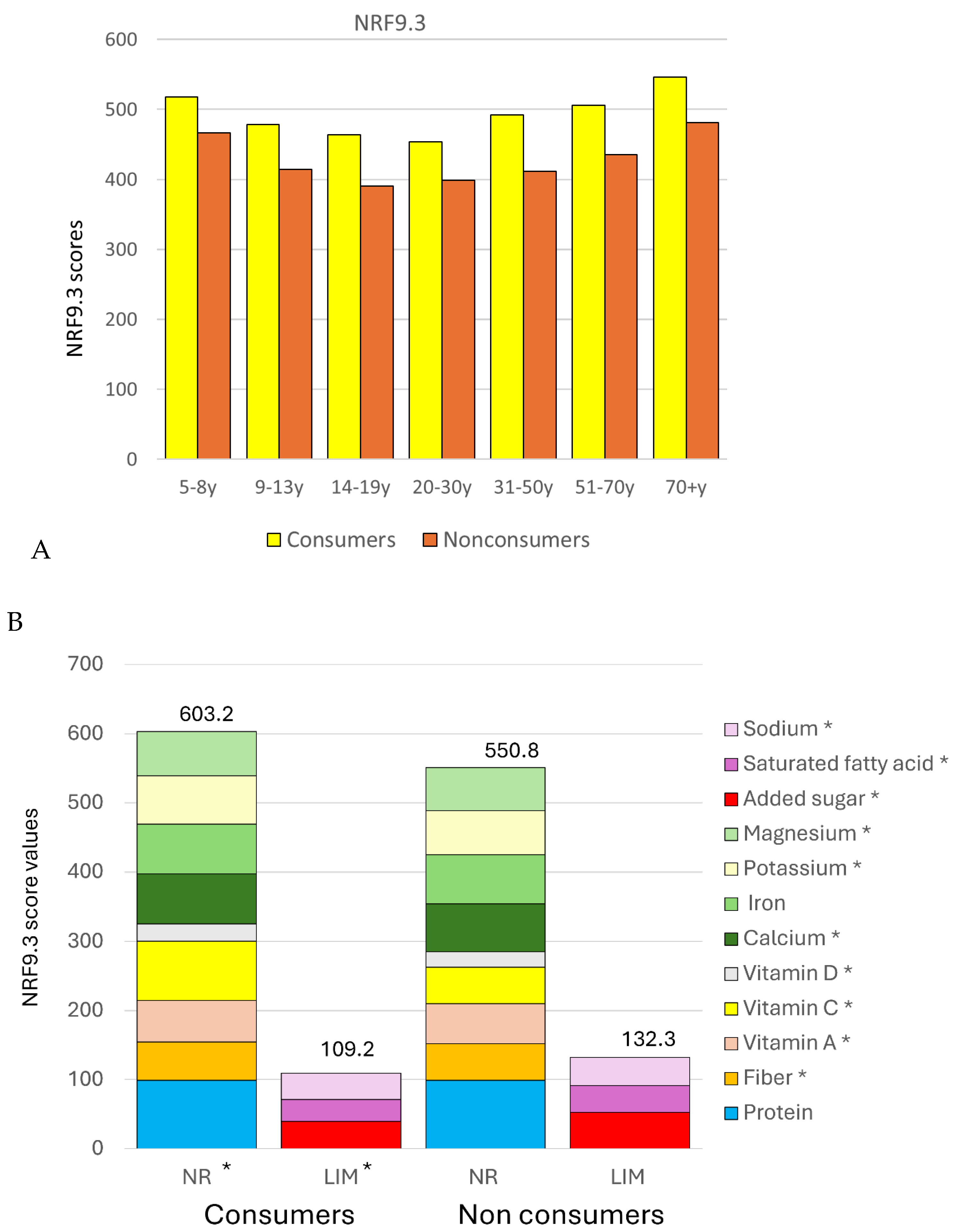

3.6. Diet Quality of Consumers and Non-Consumers of 100% Juice

4. Discussion

4.1. Low Consumption of 100% Fruit Juice

4.2. Meeting Recommendations for 100% Juice

4.3. 100% Juice Consumption and Diet Quality Metrics

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. 2020. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. Part D. Chapter 3: Beverages. 2020. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2024-12/Part%20D_Ch%203_Beverages_FINAL_508.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Drewnowski, A.; Rehm, C.D.; Constant, F. Water and beverage consumption among children age 4–13y in the United States: Analyses of 2005–2010 NHANES data. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mavadiya, H.B.; Roh, D.; Ly, A.; Lu, Y. Whole fruit versus 100% fruit juice: Revisiting the evidences and its implications for US Healthy Dietary Recommendations. Nutr. Bull. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faith, M.S.D.; Dennison, B.A.; Edmunds, L.S.; Stratton, H.H. Fruit juice intake predicts increased adiposity gain in children from low-income families: Weight status-by-environment interaction. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 2066–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe-White, K.; O’Neil, C.E.; Parrott, J.S.; Benson-Davies, S.; Droke, E.; Gutschall, M.; Stote, K.S.; Wolfram, T.; Ziegler, P. Impact of 100% fruit juice consumption on diet and weight status of children: An evidence-based review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerbach, B.J.L.; Littman, A.J.; Krieger, J.; Young, B.A.; Larson, J.; Tinker, L.; Neuhouser, M.L. Association of 100% fruit juice consumption and 3-year weight change among postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative. Prev. Med. 2018, 109, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Jarvis, S.E.; Chiavaroli, L.; Mejia, S.B.; Zurbau, A.; Khan, T.A.; Tobias, D.K.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B.; Hanley, A.J.; et al. Consumption of 100% fruit juice and body weight in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Soto, M.J.; Dunn, C.G.; Bleich, S.N. Trends and patterns in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among children and adults by race and/or ethnicity, 2003–2018. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 2405–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brauchla, M.; Dekker, M.J.; Rehm, C.D. Trends in Vitamin C Consumption in the United States: 1999–2018. Nutrients 2021, 13, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bowman, S.A.; Clemens, J.C.; Friday, J.E.; Anand, J. Changes in Total Fruit and Fruit Juice Intakes of Individuals: WWEIA, NHANES 2005–2006 to 2017–2018. 2021 Aug. In FSRG Dietary Data Briefs; Dietary Data Brief No. 41; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA): Beltsville, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Byrd-Bredbenner, C.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Fulgoni, V.L., III; Murray, R.; Pivonka, E.; Wallace, T.C. Satisfying America’s Fruit Gap: Summary of an Expert Roundtable on the Role of 100% Fruit Juice. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillot, M.; Vieux, F.; Rehm, C.; Drewnowski, A. Consumption of 100% Orange Juice in Relation to Flavonoid Intakes and Diet Quality Among US Children and Adults: Analyses of NHANES 2013-16 Data. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ferruzzi, M.G.; Tanprasertsuk, J.; Kris-Etherton, P.; Weaver, C.M.; Johnson, E.J. Perspective: The Role of Beverages as a Source of Nutrients and Phytonutrients. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maillot, M.; Rehm, C.D.; Vieux, F.; Rose, C.M.; Drewnowski, A. Beverage consumption patterns among 4–19 y old children in 2009-14 NHANES show that the milk and 100% juice pattern is associated with better diets. Nutr. J. 2018, 17, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heyman, M.B.; Abrams, S.A. Section on gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, Committee on Nutrition. Fruit Juice in Infants, Children, and Adolescents: Current Recommendations. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20170967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.html (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- US Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Research Service. Food Patterns Equivalents Database. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/fped-overview/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Shams-White, M.M.; Pannucci, T.E.; Lerman, J.L.; Herrick, K.A.; Zimmer, M.; Meyers Mathieu, K.; Stoody, E.E.; Reedy, J. Healthy Eating Index-2020: Review and Update Process to Reflect the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 123, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A.; Rehm, C.D. Socioeconomic gradient in consumption of whole fruit and 100% fruit juice among US children and adults. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vercammen, K.A.; Moran, A.J.; Zatz, L.Y.; Rimm, E.B. 100% Juice, Fruit, and Vegetable Intake Among Children in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children and Nonparticipants. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, e11–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Use of the “Healthy” Claim on Food Labelign. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-food-labeling-and-critical-foods/use-healthy-claim-food-labeling (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Front-of-Package Nutrition Labeling. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-food-labeling-and-critical-foods/front-package-nutrition-labeling (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- WHO. Guideline for Complementary Feeding of Infants and Young Children 6–23 Months of Age; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK596427/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Feeding Infants and Children from Birth to 24 Months: Summarizing Existing Guidance; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellisle, F.; Hébel, P.; Fourniret, A.; Sauvage, E. Consumption of 100% Pure Fruit Juice and Dietary Quality in French Adults: Analysis of a Nationally Representative Survey in the Context of the WHO Recommended Limitation of Free Sugars. Nutrients 2018, 10, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Agarwal, S.; Fulgoni, V.L., III; Welland, D. Intake of 100% Fruit Juice Is Associated with Improved Diet Quality of Adults: NHANES 2013–2016 Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mitchell, E.S.; Musa-Veloso, K.; Fallah, S.; Lee, H.Y.; Chavez, P.J.; Gibson, S. Contribution of 100% Fruit Juice to Micronutrient Intakes in the United States, United Kingdom and Brazil. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Murphy, M.M.; Barraj, L.M.; Brisbois, T.D.; Duncan, A.M. Frequency of fruit juice consumption and association with nutrient intakes among Canadians. Nutr. Health 2020, 26, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carnauba, R.A.; Sarti, F.M.; Hassimotto, N.M.A.; Lajolo, F.M. 100% Orange Juice Consumption is Associated with Socioeconomic Status, Improved Nutrient Adequacy, and Higher Bioactive Compounds Intake: Results from Brazilian National Dietary Survey 2017–2018. J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. 2024, 43, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Beverage Category | Classification Criteria Based on WWEAI Categories |

|---|---|

| 100% Fruit juice | 100% juices w/o added sugars: citrus juice; other fruit juice; apple juice; vegetable juice; baby juice, smoothie w/o added sugar. |

| 100% diluted fruit juice | Diluted 100% juices with a fruit juice cup equivalent > 0 and without added sugar: fruit drinks. |

| Milk and flavored milk | Milk, low fat; flavored milk, low-fat; milk, reduced fat; flavored milk, reduced fat; milk, whole; flavored milk, whole; milk, nonfat; flavored milk, nonfat |

| Drinking water | Tap water; bottled water; baby water. |

| Regular sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) | Beverages with ≥50 kcal/240 g of beverage (1 cup): coffee, tea, soft drinks, milk shakes and other dairy drinks, diet sport and energy drinks, other diet drinks, diet soft drinks, milk substitutes, fruit drinks, smoothies and grain drinks, sport and energy drinks, nutritional beverages, flavored or carbonated water, enhanced water, fruit drinks (with added sugars), other fruit juice (with added sugars), citrus juice (with added sugars). |

| Low-calorie beverages (LCBs) | Beverages with ≤50 kcal/240 g of beverage (1 cup) |

| Nutrient | Reference Value |

|---|---|

| Protein | 50 g/d |

| Fiber | 28 g/d |

| Vitamin A | 900 mcg RAE/d |

| Vitamin C | 90 mg/d |

| Iron | 18 mg/d |

| Potassium | 3500 mg/d |

| Magnesium | 420 mg/d |

| Calcium | 1300 mg/d |

| Vitamin D | 20 mcg/d |

| Added sugar | 50 g/d |

| Saturated fatty acid | 20 g/d |

| Sodium | 2300 mg/d |

| Children (n = 4086) | Adults (n = 10,925) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentages | All | 5–19 y | 5–8 y | 9–13 y | 14–19 y | 20–70 y | 20–30 y | 31–50 y | 51–70 y | >70 y | |

| All (% of total) | 100 | 20.6 | 5.2 | 7.3 | 8.1 | 79.4 | 15.2 | 26.9 | 27.2 | 10.1 | |

| Gender | Male | 48.7 | 51.0 | 52.1 | 49.7 | 51.3 | 48.1 | 50.5 | 49.3 | 47.3 | 43.6 |

| Female | 51.3 | 49.0 | 47.9 | 50.3 | 48.7 | 51.9 | 49.5 | 50.7 | 52.7 | 56.4 | |

| IPR | <1 | 13.0 | 19.0 | 21.1 | 16.9 | 19.6 | 11.5 | 16.6 | 12.0 | 10.3 | 5.4 |

| 1–1.99 | 17.1 | 20.5 | 22.4 | 20.2 | 19.7 | 16.2 | 17.7 | 16.0 | 14.3 | 19.8 | |

| 2–3.49 | 20.4 | 20.3 | 19.2 | 22.5 | 19.1 | 20.4 | 23.0 | 19.6 | 17.6 | 26.0 | |

| ≥3.5 | 39.0 | 29.9 | 28.3 | 31.0 | 29.8 | 41.3 | 30.5 | 42.8 | 47.7 | 36.6 | |

| NA | 10.5 | 10.2 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 11.8 | 10.6 | 12.2 | 9.6 | 10.1 | 12.1 | |

| Ethnicity | Other Hispanic | 8.8 | 9.9 | 11.2 | 9.3 | 9.6 | 8.5 | 12.0 | 9.3 | 7.1 | 4.8 |

| Other race | 10.7 | 14.0 | 13.2 | 14.5 | 14.1 | 9.9 | 11.8 | 11.6 | 8.8 | 5.6 | |

| NH black | 11.7 | 12.7 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 13.4 | 11.5 | 13.6 | 11.7 | 11.4 | 7.9 | |

| NH white | 59.5 | 48.1 | 48.3 | 50.4 | 45.8 | 62.5 | 52.1 | 56.8 | 67.7 | 79.4 | |

| Mex American | 9.2 | 15.3 | 15.2 | 13.5 | 17.1 | 7.7 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 5.0 | 2.3 | |

| Variable | Consumers (n = 4110) | Non-Consumers (n = 10,901) | p 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 24.5 | 75.5 | ||

| Age group | 5–8 y | 45.4 | 54.6 | <0.001 |

| 9–13 y | 37.5 | 62.5 | ||

| 14–19 y | 23.7 | 76.3 | ||

| 20–30 y | 19.2 | 80.8 | ||

| 31–50 y | 19.4 | 80.6 | ||

| 51–70 y | 22.9 | 77.1 | ||

| >70 y | 30.8 | 69.2 | ||

| Ethnicity | Other Hispanic | 31.6 | 68.4 | <0.001 |

| Other race | 22.4 | 77.6 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 21.3 | 78.7 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 34.4 | 65.6 | ||

| Mexican American | 28.0 | 72.0 | ||

| Gender | Male | 25.1 | 74.9 | 0.361 |

| Female | 23.9 | 76.1 | ||

| IPR | <1 | 29.6 | 70.4 | 0.001 |

| 1–1.99 | 26.6 | 73.4 | ||

| 2–3.49 | 24.0 | 76.0 | ||

| ≥3.5 | 22.3 | 77.7 | ||

| NA | 23.6 | 76.4 |

| Number of Servings in Cups/Day | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <0.5 | 0.5 to 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.5 | 1.5 to 2.0 | ≥2 |

| % | % | % | % | % | |

| All | 87.1 | 7.7 | 3.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| 5–8 y | 77.0 | 14.9 | 4.6 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| 9–13 y | 82.0 | 11.2 | 5.2 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| 14–19 y | 86.6 | 6.7 | 4.4 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| 20–30 y | 89.7 | 5.4 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 1.8 |

| 31–50 y | 88.5 | 6.9 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 1.1 |

| 51–70 y | 88.2 | 7.0 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| >70 y | 85.5 | 9.8 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gazan, R.; Maillot, M.; Drewnowski, A. Consumption of 100% Juice and Diluted 100% Juice Is Associated with Better Compliance with Dietary Guidelines for Americans: Analyses of NHANES 2017–2023. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2715. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17162715

Gazan R, Maillot M, Drewnowski A. Consumption of 100% Juice and Diluted 100% Juice Is Associated with Better Compliance with Dietary Guidelines for Americans: Analyses of NHANES 2017–2023. Nutrients. 2025; 17(16):2715. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17162715

Chicago/Turabian StyleGazan, Rozenn, Matthieu Maillot, and Adam Drewnowski. 2025. "Consumption of 100% Juice and Diluted 100% Juice Is Associated with Better Compliance with Dietary Guidelines for Americans: Analyses of NHANES 2017–2023" Nutrients 17, no. 16: 2715. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17162715

APA StyleGazan, R., Maillot, M., & Drewnowski, A. (2025). Consumption of 100% Juice and Diluted 100% Juice Is Associated with Better Compliance with Dietary Guidelines for Americans: Analyses of NHANES 2017–2023. Nutrients, 17(16), 2715. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17162715